Abstract

Background

Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the renal parenchyma is extremely rare, only 5 cases were reported.

Case presentation

We probably report the fifth case of primary Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the renal parenchyma in a 61-year-old female presenting with intermittent distending pain for 2 months. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) revealed hydronephrosis of the right kidney, but a tumor cannot be excluded completely. Finally, nephrectomy was performed, and histological analysis determined that the diagnosis was kidney parenchyma squamous cell carcinoma involving perinephric adipose tissue.

Conclusions

The present case emphasizes that it is difficult to make an accurate preoperative diagnosis with the presentation of hidden malignancy, such as hydronephrosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the renal pelvis is a rare neoplasm, accounting for only 0.5 to 0.8% of malignant renal tumors [1], SCC of the renal parenchyma is even less common. A review of the literature shows that only five cases of primary SCC of the renal parenchyma have been reported to date [2,3,4,5,6]. Here, we are reporting a case of primary SCC of the renal parenchyma, which was post-surgically diagnosed according to tissue pathology. A review of recent related literature is provided as well. The ethics committee of Chongqing Medical University has reviewed and approved the project and the Ethics board approval number is 2016–064.

Case presentation

The patient is a 61-year-old female. After suffering from intermittent pain in the right flank region for 2 months she was referred to the urology department at an outside hospital. The patient was diagnosed with hydronephrosis of the right kidney and underwent a right ureteroscopy with placement of a double J stent. The patient was subsequently discharged. After removal of the double J stent (which occurred 1 month following discharge), the patient presented intermittent colicky pain at the right flank region. Subsequently, the patient was referred to our department for further evaluation and treatment. The patient had reviewed and provided written consent to participate in the study. The ethics committee of Chongqing Medical University has reviewed and approved the project and the Ethics board approval number is 2016–064.

In our department, we asked about her medical history in detail. She denied having symptoms such as frequent micturition, urgent urination, odynuria, hematuria, dysuria, abdominal pain, fever, chills, nausea or vomiting. Her medical history included hypertension with blood pressure up to 160/100 mmHg. She had never taken any medication for hypertension. There was no history of prior radiation exposure or kidney stones. She denied prior smoking and alcohol consumption. Physical examination revealed mild right costovertebral angle tenderness, but was otherwise normal. We performed the following auxiliary checks: Her routine blood tests demonstrated a red blood cell count (RBC) of 4.12 × 1012/L, white blood cell count (WBC) of 10.75 × 109/L, and a total number of platelets (PLT) of 332 × 109/L. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 70 mm/h. Procalcitonin (PCT) was 0.949 ng/mL (normal, < 0.50 ng/mL). Tuberculosis T cell detection and the Tuberculin Purified Protein Derivative (PPD) test were within the normal ranges. Her serum chemistry, routine urine tests, renal and liver function were within the normal ranges as well.

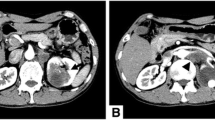

Her chest X-ray was within the normal range, but ultrasonography of the urinary system revealed heavy hydronephrosis of the right kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen showed marked hydronephrosis of the right kidney (which presented as a cyst-like structure), and some perinephric exudates (Fig. 1a-c). Further CECT (Fig. 1d-f) and CT (coronal and sagittal, Fig. 1g,h) of the abdomen revealed right gross hydronephrosis with a markedly dilated cystic pelvicalyceal system and right perinephric chronic inflammation; a tumor could not be completely ruled out in the lower pole of the right kidney due to uneven renal parenchyma and mild to moderate enhancement in the nephritic phase. Renal radionuclide imaging revealed that the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of the right kidney was 12.3 mL/min, GFR of the left kidney was 57.9 mL/min and the total GFR was 70.2 mL/min (normal GFR>64.8 mL/min). A careful study of the imaging ruled out the presence of any other systemic involvement. Infectious lesions were considered before surgery, but tumors could not be excluded. The patients and her family members refused to perform other further examinations.

a-c Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed marked hydronephrosis of the right kidney and some perinephric exudates. d-f. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed right gross hydronephrosis and right perinephric chronic inflammation; in the lower pole of the right kidney, a tumor could not be completely excluded with mild to moderate enhancement. g,h Plain scan of coronal and sagittal images

Retroperitoneal laparoscopic radical nephrectomy was performed under general anesthesia. Severe perinephric adhesions were found during the procedure (especially the hilum), therefore lymph nodes were not subjected to lymphadenectomy. It can be seen that the resected kidney specimen presented an irregular and enlarged “skin capsule” shape. The thickness of the capsule wall was uneven, and the thickening was obvious in some areas, especially in the lower pole, but there was no round or oval solid mass with any clear boundary. The resected specimen was submitted to histopathology following surgery. The pathologist evaluated the right kidney (11.0 × 6.0 × 5.0 cm) with the upper ureter (0.8 × 0.6 cm). The bisected right kidney showed a grayish white cut surface and a markedly dilated cystic pelvis, incrassated parenchyma of the lower pole, and incrassated renal capsules. The histological examination revealed well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), displaying typical morphological features of SCC (including: epithelioid cell niche, mild to moderate heterotypic cells, visible keratin pearls and intercellular bridges). Immunohistochemistry results also supported this diagnosis. Normal glomeruli and tubule structures were also observed around the cancerous foci, involving perinephric adipose tissue, but not including the renal pelvis, renal vein, or ipsilateral ureter. There was no distant metastasis. Therefore, a pathological stage of pT3aNxM0 was assigned. Immunohistochemistry showed EMA(−), CK(+++), HCK(+++), CK5/6(++), LCK(++), P63(+++), CK8(−), Ki67(++), 40% P53(+++), CerbB-2(−) (Figs. 2 and 3).

(upper) Histological examination, showing classical morphology of squamous carcinoma (HE staining, 200×). (Fig. 2 lower) immunohistochemistry, CK5/6 positive (200×)

The patient refused additional treatment after surgery. She attended the phone call follow-up for 3 months, after which she was lost to follow-up. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her immediate family for the publication of the present study.

Discussion and conclusions

SCC of the kidney is a rare clinical entity representing only 0.5 to 0.8% of malignant renal tumors [1]. SCC of the renal parenchyma is extremely rare when compared to SCC of the renal pelvis. No less than 15 literature references have reported SCC of the renal pelvis in the recent 5 years, and a current review of the literature could identify only 5 literature references concerning SCC of the renal parenchyma [2,3,4,5,6,7] (Table 1). Until recently, SCC of the renal pelvis was regarded as urothelium metaplasia [7,8,9], however, the histological origin and mechanism of renal parenchyma SCC remains unknown. It probably originates from convoluted tubules or undifferentiated stem cells of the renal mesenchyme. SCC of the kidney is frequently associated with urolithiasis and hydronephrosis [3, 5, 6]. The present patient had a history of hydronephrosis for 2 months and surgery was performed to relieve the hydronephrosis. Hydronephrosis is a predisposing factor resulting in squamous metaplasia, which may develop into SCC later on.

Due to its nonspecific clinical presentation compared to other kidney tumors, hydronephrosis presents a great challenge for early diagnosis. The main symptoms presented by the five case reports of SCC of the rena parenchyma (Table 1) are hematuria and pain. Image examinations are valuable but are non-specific. Because of the rarity and the short follow-up of the cases, a prognosis is very difficult to predict.

Ultrasonography typically only reveals only hydronephrosis. Conversely, CT is an important tool and can provide high-resolution imaging to evaluate masses and stages in renal malignancies. In the present case, CECT revealed hydronephrosis with a markedly dilated cystic pelvicalyceal system with perinephric chronic inflammation. This is consistent with the renal specimen seen after resection. Ureteral obstruction is the main cause of the presenting symptoms.

Furthermore, the significance of the case can also be considered as a lesson, which teaches us to consider the possibility of renal malignant tumors when encountering the patients with long-term hydronephrosis, uneven thickness of kidney parenchyma and uneven enhancement of CT scanning.

According to the patient’s medical history and primary clinical examinations, tuberculosis and uretero pelvic junction obstruction were rather unlikely. One of the most consistent initial diagnoses is a neoplasm with unknown character. Primary SCC of the kidney should further rule out metastatic SCC with the combination of clinical history, imaging studies, and histopathology [7, 10]. Nevertheless, it is difficult to make a definite diagnosis prior to surgery considering the nonspecific features of this case. FDG-PET/CT has been validated as an effective tool in diagnosis, preoperative evaluation and prognosis of kidney malignancies [11]. However, FDG-PET/CT were ineffective for distinguishing renal inflammation diseases from various types of tumors in some cases [6]. Renal tumors can be biopsied by puncture. Patients with hydroneprosis can be biopsied through ureteroscopy for stenosis. In addition, urocytology is helpful to determine the diagnosis of primary or invading lesions in renal pelvis and calves.

Regrettably, this patient did not undergo any examinations other than those mentioned above. The main reasons for this were as follows: 1) The imagological diagnosis showed dilation of the collecting system and chronic perinephritis, and the judgment of the tumor was not clear. 2) The Double J stent implantation was performed in an outside hospital. Due to the two reasons, it was difficult to make decisions on puncture biopsy, ureteroscopy and biopsy of stenoses. In addition, the ureteroscopy procedure may have introduced an increased the risk of tumor metastasis. 3) The positive rate of urocytology was low and not beneficial in affecting the decision to perform surgery. Meanwhile the double J stent placed in the outside hospital had just been removed before admission. Therefore, infectious lesions were primarily considered, affecting the clinical decision. Afterwards, the tumor did not invade the collective system. 4) The most important factor was the refusal of the patient and her family to undergo further medical examination as we suggested, including FDG-PET/CT because of the cost. They insisted on proceeding directly to surgery. Therefore, after the informed consent was signed, retroperitoneal laparoscopic radical nephrectomy was performed.

Because renal SCC is insensitive to chemotherapeutics and radiotherapy, the patient did not receive any further treatment. The cost of treatment was also taken into consideration. In addition, the prognosis of renal SCC is generally poor, and more extensive follow-up data is essential to evaluate the prognosis of renal parenchyma SCC.

In conclusion, SCC of the kidney parenchyma is a rare upper tract urothelial carcinoma, which presents a diagnostic challenge to the urologist and which should be considered in the patients with chronic hydronephrosis. According to the recent literature, 5 cases of renal parenchyma SCC have been reported to date (Table 1). As more cases are presented in the literature, urologists will be able to make a quick and accurate diagnosis and provide treatment of this disease by understanding its presentation and natural history.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SCC:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

- WBC:

-

White blood cell count

- PLT:

-

Total number of platelets

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- PCT:

-

Procalcitonin

- CECT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography

- PPD:

-

Tuberculin purified protein derivative

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- FDG-PET/CT:

-

[18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose- positron emission tomography-computed tomography

References

Li MK, Cheung WL. Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. J Urol. 1987;138(2):269–71.

Terada T. Synchronous squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney, squamous cell carcinoma of the ureter, and sarcomatoid carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206(6):379–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2009.07.021.

Kulshreshtha P, Kannan N, Bhardwaj R, Batra S. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the renal parenchyma. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55(3):370–1. https://doi.org/10.4103/0377-4929.101747.

Pusiol T, Zorzi MG, Morini A. Comment on: primary squamous cell carcinoma of the renal parenchyma. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2013;56(1):70. https://doi.org/10.4103/0377-4929.116160.

Ghosh P, Saha K. Primary Intraparenchymal squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney: a rare and unique entity. Case Rep Pathol. 2014;2014:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/256813.

Wang Z, Yan B, Wei YB, Hu NA, Shen Q, Li D, Yang JR, Yang X. Primary kidney parenchyma squamous cell carcinoma mimicking xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(3):2179–81. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2016.4200.

Sahoo TK, Das SK, Mishra C, Dhal I, Nayak R, Ali I, Panda D, DasMajumdar SK, Parida DK. Squamous cell carcinoma of kidney and its prognosis: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Urol. 2015;2015:469327. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/469327.

Palmer CJ, Atty C, Sekosan M, Hollowell CM, Wille MA. Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. Urology. 2014;84(1):8–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2013.11.020.

Jiang P, Wang C, Chen S, Li J, Xiang J, Xie L. Primary renal squamous cell carcinoma mimicking the renal cyst: a case report and review of the recent literature. BMC Urol. 2015;15:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-015-0064-z.

Bhaijee F. Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2012;16(2):124–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2011.08.009.

Ferda J, Ferdova E, Hora M, Hes O, Finek J, Topolcan O, Kreuzberg B. 18F-FDG-PET/CT in potentially advanced renal cell carcinoma: a role in treatment decisions and prognosis estimation. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(6):2665–72.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Qing Jiang for general supervision of the research, thank Chuan Liu and Yulong Chen for data collection, thank Lingyu Liang for language polish.

Funding

The work was supported by the Innovation Program for Chongqing’s Overseas Returnees (2019), High-level Medical Reserved Personnel Training Project of Chongqing (the 4th batch), and Research Program of Basic Science and Frontier Technology in Chongqing (cstc2017jcyjAX0435) .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Here we state XRZ contribute to acquisition and analysis of the case, draft of the work and interpretation of the data. YFZ, CGG and JYZ contributes to the drafted the work and substantively revised it. PHL made substantial contributions to the conception, design of the work, interpretation of data, provide the funding, drafted the work or substantively revised it. The author (s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of Chongqing Medical University has reviewed and approved the project and the Ethics board approval number is 2016–064. The patient had reviewed and had written consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

The informed consent was obtained from the patient as written.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., Ge, C. et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal parenchyma presenting as hydronephrosis: a case report and review of the recent literature. BMC Urol 20, 107 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-020-00676-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-020-00676-5