Abstract

Background

Hip fractures are a major public health concern among middle-aged and older adults. It is important to understand the associated risk factors to inform health policies and develop better prevention strategies. Musculoskeletal pain is a possible implicating factor, being associated with physical inactivity and risk of falls. However, the association between musculoskeletal pain and hip fractures has not been clearly investigated.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of the Chinese population was obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). The study collected patient information on their demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, other health-related behavior, and history of musculoskeletal pain and hip fractures. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to investigate the factors influencing the risk of hip fracture, including factors related to the individual and to musculoskeletal pain. P for trend test was performed to assess the trend of each continuous variable. The robustness and bias were assessed using the bootstrap method. Restricted cubic spline regression was utilized to identify linear or non-linear relationships.

Results

Among the 18,813 respondents, a total of 215 individuals reported that they have experienced a hip fracture. An increased risk of hip fracture was associated with the presence of waist pain and leg pain (P < 0.05), as well as with an increased number of musculoskeletal pain sites (P < 0.05). For individuals aged 65 and above, a significant association was found between age and the risk of hip fracture (P < 0.05). Furthermore, respondents with lower education level had a higher risk of hip fracture compared to those with higher education levels (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

In the Chinese population, the risk of hip fracture was found to be associated with both the location and extent of musculoskeletal pain, as well as with other factors such as age and demographic characteristics. The findings of this study may be useful for informing policy development and treatment strategies, and provide evidence for comparison with data from other demographic populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Musculoskeletal pain is a highly prevalent health issue, particularly among the elderly population, affecting up to 74% of older adults in global communities [1,2,3]. Musculoskeletal pain may be associated with prior injury or neuropathic causes, but in the majority of cases is idiopathic and as such requires long-term management [4]. Its chronic nature imposes a substantial burden on both individuals and society, leading to restricted physical function, diminished quality of life, and disability, which on the societal level result in significant loss of productivity and demand of healthcare resources [5]. The latest analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study reported that in 2016, lower back pain ranked first and neck pain ranked sixth out of 30 major diseases and injuries contributing to years lived with disability [6]. Musculoskeletal pain commonly manifests in multiple anatomical sites. Various studies have reported that approximately 41–75% of individuals experience pain in two or more sites, although the prevalence may vary depending on the population studied and the number of pain sites assessed [3, 7, 8]. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that compared to single-site pain, multi-site pain is linked to worse health outcomes including reduced physical function and health-related quality of life, impaired cognitive function and sleep quality, and heightened depressive symptoms [9,10,11,12,13].

Fractures pose a significant health concern globally, frequently resulting in morbidity and mortality particularly for elderly individuals, and can lead to heightened susceptibility to recurring fractures [14,15,16]. Significant risk factors for fractures include aging, osteoporosis, and falls [17]. Some associations of these same factors with musculoskeletal pain have been found. For instance, studies have revealed that experiencing musculoskeletal pain at particular sites within the body and also having multiple pain sites can separately increase the likelihood of falls [18, 19]. Furthermore, research has confirmed that having musculoskeletal pain in multiple sites is linked to the risk of fractures, even after adjusting for the risk of falls [20]. Among different types of fractures, hip fractures in particular pose a significant public health concern among individuals aged 60 and above, leading to untimely mortality, severe disability, and a decline in functional independence [21,22,23]. Patients who experience hip fractures are frequently at higher risk of complications such as cardiovascular and infectious diseases, bedsores, bleeding, and depression, which can ultimately result in death [24]. Recent studies have estimated the worldwide 1-year mortality rate for hip fractures at approximately 22%, with nearly 50% of survivors experiencing a loss of functional independence [25, 26]. The Burden of Disease Study in China identified hip fracture as a primary cause of years lived with disability among 32 different injury types [27].

Because hip fractures are associated with the socioeconomic consequences of chronic patient management and increased mortality in the elderly, it is important to gain a better understanding of the risk factors to inform health policies and develop prevention strategies. The nature of the primary patient population, consisting of older adults has posed certain barriers to investigation such as loss of follow-up. Recently, there was a greater emphasis on studying the prevention of hip fractures and exploring the related risk factors. However, there is still a lack of research on the association between musculoskeletal pain and hip fractures [28]. Current investigations of the relationship between musculoskeletal pain and fractures have been more focused on vertebral fractures, or reporting the incidence and cause of different types of fractures [29,30,31,32]. Limited studies have specifically investigated the association between musculoskeletal pain and hip fractures. In one study, Adren et al. reported that knee pain was a risk factor for hip fractures [33]. However, musculoskeletal pain often affects multiple sites, and the location of pain as well as multi-site compared to single-site pain may have different influences on the risk of hip fractures, although these associations have never been studied. An improved understanding of these associations is essential for advancing the knowledge base and informing healthcare strategies, particularly for fracture prevention and also reduction of hip fracture-related mortality in older adults. This study uses the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) database, which contains a nationally representative sample of the Chinese population, to explore relationship between musculoskeletal pain and hip fractures. The study hypothesis is that the risk of hip fracture is associated with musculoskeletal pain at specific sites, as well as with the number of pain sites. The findings of this study enrich the current knowledge base and provide evidence from an ethnic population, which may be used as a point of comparison for future epidemiological studies.

Methods

Study population

This study analyzed data from the most recent follow-up questionnaire of CHARLS, which is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the Chinese population conducted by the National School of Development of Peking University. The survey focuses on the middle-aged and elderly population in China, and includes interviews with Chinese residents aged 45 years or older and their spouses in their household. These interviews capture information about the respondents’ social, economic, and health status. The original CHARLS study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Peking University (approval number: IRB00001052-11015), and all data collection and analysis methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Additionally, all respondents provided informed consent at the time of participation. A detailed description of CHARLS has been previously published [34].

The CHARLS database has been updated with follow-up surveys since the original study. Using the latest available CHARLS data from 2018, this study analyzed the risk factors of hip fractures, including individual factors and factors related to musculoskeletal pain. The inclusion criteria for the present study were: (1) individuals aged at least 45 years old in CHARLS 2018; (2) and having data regarding musculoskeletal pain. Exclusion criteria were: (1) missing data of demographics and medical information; (2) persons aged less than 45 years old; (3) missing data of musculoskeletal pain in CHARLS 2018; (4) persons without musculoskeletal pain. After data screening, 1003 respondents were excluded for missing data, a total of 18,813 respondents met the inclusion criteria for this study (Fig. 1).

Data collection and preprocessing

The household interview collected information on demographic characteristics including gender, age, residential address, marital status, and employment status. Socioeconomic information, including education level and insurance status, was also recorded. Additionally, health-related behavior such as smoking and alcohol consumption were documented.

Regarding data collection for this study, participants were initially interviewed to determine if they experienced any physical pain. If the response was categorized as ‘a little’, ‘somewhat’, ‘quite a bit’, or ‘very’, participants were then asked to identify the specific body part(s) where they were currently experiencing pain. The participants were also inquired about any past instances of hip fracture.

Information collected from participants were categorized into groups based on their demographic characteristics. The musculoskeletal pain sites surveyed included the neck, shoulder, arm, wrist, fingers, back, waist, leg, knees, ankle, and toes. Some pain sites, such as the head, chest, and stomach, were excluded due to their association with visceral diseases. The number of pain sites was calculated based on the respondent’s answers regarding pain sites.

Statistical analysis

This study utilized the mostly recently available 2018 CHARLS data to investigate the risk factors contributing to hip fractures. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted for different subgroups using chi-square tests and logistic regression. The regression models were performed stepwise, first adjusting for age, gender, residence, education, marital status, smoking, drinking, and employment status, and then further adjusting for musculoskeletal pain. P for trend test was performed to assess the trend of each continuous variable. The robustness and bias of parameter estimation were assessed using the bootstrap method. Restricted cubic spline regression was utilized to identify linear or non-linear relationships between variables. All data cleaning, processing, analysis, and calculations were carried out using R version 4.2.1. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics data

Among the 19,816 participants from the 2018 CHARLS database, 18,813 respondents with relevant data were included in this study. The demographic characteristics of the included respondents are presented in Table 1. The mean age of respondents was 62 years, with a majority being female, married, and residing in rural areas. Almost half of the respondents had no formal education. The resident insurance coverage rate exceeded 90%.

Relationship between hip fractures and anatomical site of musculoskeletal pain

The results of correlation analysis between musculoskeletal pain and hip fractures is presented in Table 2. It was found that respondents experiencing waist pain and leg pain had a higher risk of hip fracture (P < 0.05). The correlation between pain sites and hip fractures is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Relationship between hip fractures and the number of pain sites

As shown in Table 2, when musculoskeletal pain occurs in more than 4 anatomical sites, an increased number of pain sites up to 8 total sites is significantly associated with a higher risk of hip fracture (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the correlation between the number of pain sites and hip fractures is depicted in Fig. 3.

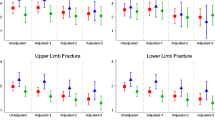

Relationship between hip fractures and other individual factors

Among the 18,813 respondents, a total of 215 individuals reported that they have experienced a hip fracture. Table 3 presented the results of correlation analysis between various individual factors and hip fractures. The outcomes of multi-factor analysis are shown in Fig. 4. It was observed that among all non-pain-related individual factors, the occurrence of hip fractures was primarily associated with age and education level. Notably, the risk of hip fractures was found to increase with age among individuals aged 65 and above (P < 0.05). Additionally, respondents with lower education level exhibited a higher risk of hip fracture compared to those with higher education levels (P < 0.05). The correlation trend of both age and education level was tested to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). Moreover, the estimated regression coefficients of most variables had minimal bias, indicating a considerable overall robustness in their estimation. It was found that the association between age and fracture followed a linear relationship (Supplementary materials).

Discussion

Hip fractures are associated with high mortality rates and significant costs, posing a major healthcare problem that also has devastating impacts on the individual, such as impaired physical function and quality of life particularly in the elderly [30, 35]. Factors contributing to an increased risk of hip fractures were of particular interest for investigation in this study as past studies in 2011 and 2013 using CHARLS data have indicated that China has a higher incidence of hip fractures compared to the United States and Japan [36, 37]. A recent report estimated that approximately 1,000 men and 1,000 women per 100,000 community residents in China experience hip fractures [38]. This study used the latest 2018 CHARLS data to analyze the risk factors contributing to the occurrence of hip fractures in the Chinese population. The findings suggested that an increased risk of hip fractures was associated with various individual factors of the respondents, the presence and location of musculoskeletal pain, and the number of pain sites. Gaining a better understanding of these influencing factors is crucial for preventing hip fractures among the elderly and reducing future mortality rates.

Musculoskeletal pain as a factor influencing the risk of hip fractures

Although the association between musculoskeletal pain and hip fractures has been rarely explored, several studies have reported the relationship between musculoskeletal pain at different body sites and other types of fractures such as vertebral fracture [20, 31, 32]. This study confirmed a statistically significant risk of hip fracture associated with musculoskeletal pain in the waist and leg.

Both waist pain and leg pain have known impacts on central as well as lower limb proprioception, crucial for lower limb muscle strength and joint stability. These factors are positively correlated with falls risk and can contribute to the occurrence of hip fracture [39,40,41]. Therefore, for elderly individuals experiencing musculoskeletal pain, healthcare practitioners should pay particular attention to pain in the waist and leg, as these may play a greater role in hip fracture than pain at other body sites.

Number of musculoskeletal pain sites and the risk of hip fractures

Previous studies have reported that individuals who experience pain at multiple sites, including the neck, back, hands, shoulders, hips, knees, and feet, are at increased risk of vertebral and non-vertebral (such as femoral, radial, ulnar, rib, and humeral) fractures [20]. However, hip fractures have been rarely reported in these studies due to their high mortality rate. Important to the knowledge base in this respect, the findings of this study suggest that the risk of hip fracture increases with the number of pain sites across 11 different areas in the body, namely the neck, back, waist, shoulders, arms, wrists, fingers, legs, knees, ankles, and toes. There is evidence that patients with multi-site pain have moderately elevated levels of systemic inflammation, reduced anti-inflammatory markers, and enhanced innate immunity [42,43,44,45]. These changes may induce a systemic reduction in bone strength due to bone remodeling from the effects of inflammation, thereby increasing the risk of fracture. Furthermore, other reports have reflected that an increase in the number of pain sites additively limits basic daily activities in the elderly [46,47,48]. This restriction of activity is often associated with multiple deleterious effects such as decline in muscle strength, balance ability, and physiological functions, as well as predisposition to or exacerbation of musculoskeletal diseases such as osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. These factors may individually or in combination increase the risk of falls in the elderly and also lead to an increased risk of hip fractures.

Demographic factors influencing the risk of hip fractures

This study found that an increased risk of hip fractures was associated with a number of individual factors, which may provide new areas of focus when developing prevention strategies. Consistent with other studies [49,50,51], this study showed increased hip fracture risk with older age in people over 65 years. This association is likely due to declining physiological function with age, which may be a cause or consequence of decreases in physical activity, muscle strength, proprioception of the lower extremities, and physical reactive balance. These aging changes, together with an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures all increase the risk of hip fractures in older adults [52,53,54]. A particularly interesting finding from this study was that higher education levels were inversely associated with the risk of hip fracture. This may be partly due to the influence of education on individual behavior, such as elective levels of physical activity, nutritional supplementation, smoking, and alcohol consumption [55]. Some studies have also reported poorer outcomes for orthopedic patients who had received lower levels of education, manifested as higher pain scores, reduced range of motion, and poorer functional outcomes following intervention [56, 57].

Study strengths and limitations

This study used the 2018 CHARLS data to conduct a detailed analysis of the risk factors associated with hip fractures in the Chinese population. The demographic characteristics of 18,813 participants were examined, 215 of whom had previously experienced a hip fracture. This incidence rate was consistent with findings from previous studies conducted within Chinese communities [38]. The study strengths arise from the ability to comprehensively analyze a large population sample, encompassing information on the participants’ demographics, pain data, and history of hip fractures. This comprehensive information enabled subgroup analyses based on age, sex, socioeconomic status, and health-related behavior, as well as trend tests to elucidate the factors contributing to increased hip fracture risk. The associations found to exist with different individual characteristics and pain sites constitute an important contribution to knowledge in the field, and serve as a point of comparison for future studies in other populations as well as a guide for devising prevention or intervention strategies.

This study has some limitations which may affect the interpretation of findings, primarily due to the nature of the CHARLS study from which data was drawn for analysis. Firstly, it is important to note that hip fractures assessment in CHARLS data relied on self-reporting and was not confirmed by clinical imaging, which could potentially lead to inaccuracies in the reported rate of fractures. Secondly, CHARLS data is focused on Chinese community residents aged 45 years and older, which may have led to an underestimation of hip fracture incidence since older age is associated with a higher risk of hip fractures. This factor may have impacted the analysis of associations with musculoskeletal pain. Thirdly, respondents with a greater number of pain sites may have better recollection and accuracy in reporting fractures compared to those with no or few pain sites. As respondents with multiple pain sites are a minority, the incidence of hip fractures could be underestimated in the sample used for this study, particularly if some of the respondents have experienced the fracture early in life but have forgotten about the experience at the time of the survey. Despite these limitations, the associations found between the risk of hip fractures and factors relating to the individual and musculoskeletal pain in this study provide valuable insights, and were drawn from a large and nationally representative sample of middle-aged and older adults, with important implications for public health and policy development.

Conclusions

Based on data from the 2018 CHARLS survey, the risk of hip fractures was found to be associated with the location and number of body sites experiencing musculoskeletal pain, as well as with other non-pain-related individual factors. The findings of this study may be useful for guiding policy development, treatment strategies, and scientific or clinical study design.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data was from http://charls.pku.edu.cn/.

References

Karttunen NM, Turunen JH, Ahonen RS, Hartikainen SA. Persistence of noncancer-related musculoskeletal chronic pain among community-dwelling older people: a population-based longitudinal study in Finland. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:79–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/ajp.0000000000000089

Thomas E, Peat G, Harris L, Wilkie R, Croft PR. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain. 2004;110:361–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.017

Patel KV, Guralnik JM, Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: findings from the 2011 national health and aging trends study. Pain. 2013;154:2649–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.029

Slater H, Briggs AM. Models of care for musculoskeletal pain conditions: driving change to improve outcomes. Pain Manag. 2017;7:351–7. https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt-2017-0025

Blyth FM, Noguchi N. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and its impact on older people. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:160–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2017.10.004

Global regional. National incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32154-2

Solidaki E, Chatzi L, Bitsios P, Markatzi I, Plana E, Castro F, Palmer K, Coggon D, Kogevinas M. Work-related and psychological determinants of multisite musculoskeletal pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;36:54–61. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.2884

Coggon D, Ntani G, Palmer KT, Felli VE, Harari R, Barrero LH, Felknor SA, Gimeno D, Cattrell A, Vargas-Prada S, Bonzini M, Solidaki E, Merisalu E, Habib RR, Sadeghian F, Masood Kadir M, Warnakulasuriya SSP, Matsudaira K, Nyantumbu B, Sim MR, Harcombe H, Cox K, Marziale MH, Sarquis LM, Harari F, Freire R, Harari N, Monroy MV, Quintana LA, Rojas M, Salazar Vega EJ, Harris CE, Serra C, Martinez MJ, Delclos G, Benavides FG, Carugno M, Ferrario MM, Pesatori AC, Chatzi L, Bitsios P, Kogevinas M, Oha K, Sirk T, Sadeghian A, Peiris-John RJ, Sathiakumar N, Wickremasinghe RA, Yoshimura N, Kelsall HL, Hoe VCW, Urquhart DM, Derrett S, McBride D, Herbison P, Gray A. Patterns of multisite pain and associations with risk factors. Pain. 2013;154:1769–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.039

Pan F, Byrne KS, Ramakrishnan R, Ferreira M, Dwyer T, Jones G. Association between musculoskeletal pain at multiple sites and objectively measured physical activity and work capacity: results from UK Biobank study. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22:444–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2018.10.008

Lacey RJ, Belcher J, Rathod T, Wilkie R, Thomas E, McBeth J. Pain at multiple body sites and health-related quality of life in older adults: results from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:2071–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keu240

Nicholl BI, Mackay D, Cullen B, Martin DJ, Ul-Haq Z, Mair FS, Evans J, McIntosh AM, Gallagher J, Roberts B, Deary IJ, Pell JP, Smith DJ. Chronic multisite pain in major depression and bipolar disorder: cross-sectional study of 149,611 participants in UK Biobank. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:350. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0350-4

Westoby CJ, Mallen CD, Thomas E. Cognitive complaints in a general population of older adults: prevalence, association with pain and the influence of concurrent affective disorders. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:970–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.11.011

Chen Q, Hayman LL, Shmerling RH, Bean JF, Leveille SG. Characteristics of chronic pain associated with sleep difficulty in older adults: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the elderly (MOBILIZE) Boston study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1385–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03544.x

Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA 3rd, Berger M. Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:721–39. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.721

Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA. Risk of subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture in men and women. JAMA. 2007;297:387–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.4.387

Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet. 1999;353:878–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(98)09075-8

Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY, Cauley JA, Ensrud K, Browner WS, Nevitt MC, Cummings SR. BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1947–54. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.1947

Muraki S, Akune T, Oka H, En-Yo Y, Yoshida M, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H, Yoshimura N. Prevalence of falls and the association with knee osteoarthritis and lumbar spondylosis as well as knee and lower back pain in Japanese men and women. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1425–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20562

Patel KV, Phelan EA, Leveille SG, Lamb SE, Missikpode C, Wallace RB, Guralnik JM, Turk DC. High prevalence of falls, fear of falling, and impaired balance in older adults with pain in the United States: findings from the 2011 national health and aging trends study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1844–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13072

Pan F, Tian J, Aitken D, Cicuttini F, Jones G. Pain at multiple sites is associated with prevalent and incident fractures in older adults. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:2012–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3817

Cauley JA, Chalhoub D, Kassem AM, Fuleihan Gel H. Geographic and ethnic disparities in osteoporotic fractures. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:338–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.51

Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colón-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B, Boonen S. Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:380–90. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00008

Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:897–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-004-1627-0

Accelerated surgery versus standard care in hip fracture (HIP ATTACK). An international, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395:698–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30058-1

Downey C, Kelly M, Quinlan JF. Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture - a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2019;10:166–75. https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v10.i3.166

Cooper C, Cole ZA, Holroyd CR, Earl SC, Harvey NC, Dennison EM, Melton LJ, Cummings SR, Kanis JA. Secular trends in the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1601-6

Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020; 396: 1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30925-9

Scaturro D, Vitagliani F, Terrana P, Tomasello S, Camarda L, Letizia Mauro G. Does the association of therapeutic exercise and supplementation with sucrosomial magnesium improve posture and balance and prevent the risk of new falls? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34:545–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-021-01977-x

Vranken L, Wyers CE, van den Bergh JPW, Geusens P. The phenotype of patients with a recent fracture: a literature survey of the fracture liaison service. Calcif Tissue Int. 2017;101:248–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-017-0284-1

Panula J, Pihlajamäki H, Mattila VM, Jaatinen P, Vahlberg T, Aarnio P, Kivelä SL. Mortality and cause of death in hip fracture patients aged 65 or older: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:105. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-105

Kuroda T, Shiraki M, Tanaka S, Shiraki Y, Narusawa K, Nakamura T. The relationship between back pain and future vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1984–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b0c97a

Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Stone KL, Palermo L, Black DM, Bauer DC, Genant HK, Hochberg MC, Ensrud KE, Hillier TA, Cauley JA. Risk factors for a first-incident radiographic vertebral fracture in women > or = 65 years of age: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:131–40. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.041003

Arden NK, Crozier S, Smith H, Anderson F, Edwards C, Raphael H, Cooper C. Knee pain, knee osteoarthritis, and the risk of fracture. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:610–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22088

Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys203

Zhang C, Feng J, Wang S, Gao P, Xu L, Zhu J, Jia J, Liu L, Liu G, Wang J, Zhan S, Song C. Incidence of and trends in hip fracture among adults in urban China: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003180. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003180

Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302:1573–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1462

Tamaki J, Fujimori K, Ikehara S, Kamiya K, Nakatoh S, Okimoto N, Ogawa S, Ishii S, Iki M. Estimates of hip fracture incidence in Japan using the national health insurance claim database in 2012–2015. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30:975–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-04844-8

Long H, Cao R, Zhang H, Qiu Y, Yin H, Yu H, Ma L, Diao N, Yu F, Guo A. Incidence of hip fracture among middle-aged and older Chinese from 2013 to 2015: results from a nationally representative study. Arch Osteoporos. 2022;17:48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-022-01082-0

Hicks C, Levinger P, Menant JC, Lord SR, Sachdev PS, Brodaty H, Sturnieks DL. Reduced strength, poor balance and concern about falls mediate the relationship between knee pain and fall risk in older people. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1487-2

Chen X, Qu X. Age-related differences in the relationships between lower-limb joint proprioception and postural balance. Hum Factors. 2019;61:702–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720818795064

Xiao F, Maas H, van Dieën JH, Pranata A, Adams R, Han J. Chronic non-specific low back pain and ankle proprioceptive acuity in community-dwelling older adults. Neurosci Lett. 2022;786:136806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136806

Cauley JA, Barbour KE, Harrison SL, Cloonan YK, Danielson ME, Ensrud KE, Fink HA, Orwoll ES, Boudreau R. Inflammatory markers and the risk of hip and vertebral fractures in men: the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS). J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:2129–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2905

Cauley JA, Danielson ME, Boudreau RM, Forrest KY, Zmuda JM, Pahor M, Tylavsky FA, Cummings SR, Harris TB, Newman AB. Inflammatory markers and incident fracture risk in older men and women: the health aging and body composition study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1088–95. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.070409

Eriksson AL, Movérare-Skrtic S, Ljunggren Ö, Karlsson M, Mellström D, Ohlsson C. High-sensitivity CRP is an independent risk factor for all fractures and vertebral fractures in elderly men: the MrOS Sweden study. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:418–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2037

Generaal E, Vogelzangs N, Macfarlane GJ, Geenen R, Smit JH, Dekker J, Penninx B. Basal inflammation and innate immune response in chronic multisite musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2014;155:1605–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2014.05.007

Jönsson T, Ekvall Hansson E, Thorstensson CA, Eek F, Bergman P, Dahlberg LE. The effect of education and supervised exercise on physical activity, pain, quality of life and self-efficacy - an intervention study with a reference group. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:198. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2098-3

Eckstrom E, Neukam S, Kalin L, Wright J. Physical activity and healthy aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 2020;36:671–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2020.06.009

Thomas E, Battaglia G, Patti A, Brusa J, Leonardi V, Palma A, Bellafiore M. Physical activity programs for balance and fall prevention in elderly: a systematic review. Med (Baltim). 2019;98:e16218. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000016218

Chen JS, Sambrook PN, Simpson JM, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, Seibel MJ, Lord SR, March LM. Risk factors for hip fracture among institutionalised older people. Age Ageing. 2009;38:429–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afp051

Xia WB, He SL, Xu L, Liu AM, Jiang Y, Li M, Wang O, Xing XP, Sun Y, Cummings SR. Rapidly increasing rates of hip fracture in Beijing, China. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:125–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.519

Rapp K, Büchele G, Dreinhöfer K, Bücking B, Becker C, Benzinger P. Epidemiology of hip fractures: systematic literature review of German data and an overview of the international literature. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;52:10–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-018-1382-z

Hirase T, Okubo Y, Menant J, Lord SR, Sturnieks DL. Impact of pain on reactive balance and falls in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2020;49:982–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa070

Li X, Zhang W, Zhang W, Tao K, Ni W, Wang K, Li Z, Liu Q, Lin J. Level of physical activity among middle-aged and older Chinese people: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1682. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09671-9

Marks R, Allegrante JP, Ronald MacKenzie C, Lane JM. Hip fractures among the elderly: causes, consequences and control. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2:57–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00045-4

Laaksonen M, Talala K, Martelin T, Rahkonen O, Roos E, Helakorpi S, Laatikainen T, Prättälä R. Health behaviours as explanations for educational level differences in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a follow-up of 60 000 men and women over 23 years. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18:38–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckm051

Greene ME, Rolfson O, Nemes S, Gordon M, Malchau H, Garellick G. Education attainment is associated with patient-reported outcomes: findings from the Swedish hip arthroplasty register. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1868–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3504-2

Kugelman DN, Haglin JM, Carlock KD, Konda SR, Egol KA. The association between patient education level and economic status on outcomes following surgical management of (fracture) non-union. Injury. 2019;50:344–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.12.013

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No.7212118, L222087 and L232094).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project conceptualization: Mei, F.Y., Xing, D. & Lin, J.H. Study design: Mei, F.Y., Dong, S.J. & Xing, D. Data collection/validation: Mei, F.Y., Dong, S.J. & Xing, D. Data analysis: Mei, F.Y. & Dong, S.J. Result interpretation: Mei, F.Y., Li, J.J. & Xing, D. Reporting & editing: Mei, F.Y., Li, J.J., Xing, D. & Lin, J.H. Final approval of the version to be submitted: Mei, F.Y., Dong, S.J., Li, J.J., Xing, D., & Lin, J.H. Project guarantor: Xing, D. & Lin, J.H. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The CHARLS study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (approval number: IRB00001052-11,015). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and all participants signed informed consent forms when participating.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Sup Fig. 1

Histogram of bootstrapped samples of coefficients

Supplementary Material 2: Sup Fig. 2

Restricted cubic spline graph of adjusted odds ratio between age and fracture

Supplementary Material 3: Supplementary Table 1

Bootstrap statistics of all coefficients

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mei, F., Li, J.J., Lin, J. et al. Multidimensional characteristics of musculoskeletal pain and risk of hip fractures among elderly adults: the first longitudinal evidence from CHARLS. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 25, 4 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-07132-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-07132-z