Abstract

Background

The purpose of the study is to evaluate clinical and radiological outcomes in those patients with femoral head fracture, treated with open reduction and internal fixation through Gibson approach and Ganz flip trochanter osteotomy. The treatment of Pipkin fractures is very challenging, especially for small trauma centers, because of the unusual fracture patterns and high-level surgical skills required.

Case presentation

Between 2017 and 2020, nine cases of Pipkin fractures came to the Emergency Department at the Trauma Center of our Hospital in Rome. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of femoral head fracture, the open reduction and internal fixation as surgical choice and at least 24 months follow-up. Patients older than 65 years and those treated through total hip replacement or combined hip procedure (CHP) were excluded. Thus, five patients were included in our case series. The clinical outcome was evaluated according to Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index, Vail Hip score, modified Harris Hip score and Merle D’Aubignè Postel score. Radiographic assessment was scored according to Epstein-Thompson classification and heterotopic ossification was assessed through Brooker classification. The mean follow-up was 24 months (range 12-24). Average modified Harris Hip score was 92.1 points (range 75.9–100), and the average Vail score was 81.8 (range 55-95). WOMAC score was assessed in three different subscales, pain (A), stiffness (B) and physical condition (C), with the following results: 1.4 A (range 0-7), 1.2 B (range 0-6) and 6.4 C (range 0-22). Merle d’Aubignè Postel score resulted excellent for four patients and good for one patient. According to Epstein-Thompson score of the radiological outcome, four patients showed a good result and one a fair result. No mechanical or infective complications occurred in the five patients.

Conclusions

Gibson’s approach and surgical hip dislocation through Ganz trochanteric flip osteotomy allow a good exposure of the femoral head and acetabulum, giving us the possibility to perform an anatomical reduction of the fracture. In our case series, satisfactory clinical and radiological short-term results were obtained without significant complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

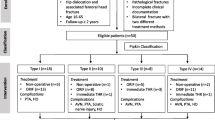

Femoral head fracture is a rare occurrence in the daily practice of a Trauma surgeon, often as a result of a high-energy trauma, such as road traffic accidents or falls from heights [1]. Nowadays the Orthopaedic Trauma Association and Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO) Foundation classifies these fractures as type 31C [2], but since 1957, the classification system introduced by Garrett Pipkin is commonly used [3]. Pipkin divided femoral head fractures in 4 categories: type 1 and type 2 are simple femoral head fractures, which are distinguished based on the involvement of the weight-bearing surface of the femoral head (type 2). In type 3, there is a concomitant femoral neck fracture, and in type 4 there is an associated acetabulum fracture, often the posterior wall due to the frequent association with posterior hip dislocation [4]. Diagnosis is based on X-rays as a first level diagnostic, but a CT-scan is needed to better understand the fracture and choose the best treatment option.

The treatment of Pipkin fractures is very challenging, especially for small trauma centers, because of the unusual fracture patterns and high-level surgical skills required [5]. There are different options for surgical treatment: small fragments excision in Pipkin I and total hip replacement in Pipkin III, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the femoral head fracture. Surgical dislocation of the hip is commonly required to reduce and fix the femoral head fragment. However, this procedure is associated with a high risk of damaging the ascending branch of the medial femoral circumflex artery, which is the most important blood supplier of the femoral head [6].

Several types of surgical approaches have been observed over the years: the anterior (Smith-Petersen, Hueter), antero-lateral (Watson-Jones) and posterior approach (Kocker-Langenbeck) are among the most used. We chose the modified Gibson approach as described by Moed in 2010 [7], using a straight skin incision. A more anterior interval is used, without violation of the gluteus maximus muscle fibers, preserving its neurovascular supply. Historically, treatment results have been rather poor, with high rates of early posttraumatic arthritis, osteonecrosis of the femoral head, heterotopic ossifications and sciatic nerve palsy.

Avascular necrosis of the femoral head is more frequent with the classical anterior or posterior approach, but the risk can be reduced using surgical hip dislocation through Ganz flip trochanter step osteotomy [8]. This surgical technique allows the simultaneous exposure of the acetabulum and the femoral head, without compromising the femoral head blood supply [9].

The aim of our retrospective cohort study was to describe clinical and radiological outcomes of a series of Pipkin fractures in our Department, treated by ORIF through surgical hip dislocation according to Ganz.

Methods

Patients

Between 2017 and 2019, nine cases of Pipkin fractures came to the Emergency Department at the Trauma Center of our Hospital in Rome. The year 2020 was excluded from the time interval, due to a progressive reduction of the emergency activities not COVID-19-related in our Hospital [10]. All fractures were caused by high-energy traffic accidents resulting in posterior hip dislocation. Hip dislocations were reduced in the emergency room in the first 6 h after the trauma, subsequently a distal femoral skeletal traction was positioned. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of femoral head fracture, the ORIF as surgical choice and at least 24 months follow-up. Patients older than 65 years and those treated through total hip replacement or combined hip procedure (CHP) were excluded. Average age was 39.8 years (range 17-53), four patients were male and one was a female. After following these inclusion criteria, five patients were included in the study, as they were treated by the same surgeon using ORIF with Gibson approach and surgical hip dislocation according to Ganz (Table 1).

Femoral head fractures were diagnosed after complete radiographic investigation, including antero-posterior and Judet views. All patients underwent CT scan with multiplanar and 3D reconstructions to understand the fracture pattern and to accurately plan surgery.

According to Pipkin’s classification and AO-OTA classification, four fractures were classified as Pipkin II (31C1.3 AO Classification) (Fig. 1), one as Pipkin IV, due to a posterior wall fracture of the left acetabulum (31C1.3 + 62A1.2 AO Classification) (Fig. 2). The STROBE guidelines were used to ensure the reporting of this observational study [11].

A 33-year-old woman (a-e) and a 17-year old man (f-i) with left femoral head Pipkin type II fracture treated by ORIF through Gibson approach and surgical dislocation with Ganz trochanteric flip osteotomy. The preoperative antero-posterior (AP) hip radiograph, axial CT and CT 3-D reconstruction after injury (a-c, f-h) and post-operative and final follow-up radiographs (d, e, i, l)

A 49 -year-old man (a-e) with a fracture of the left femoral head (Pipkin type IV) and of the posterior wall of the left acetabulum, treated by ORIF through Gibson approach and surgical hip dislocation with Ganz trochanteric flip osteotomy. The preoperative AP radiograph, axial CT and CT 3-D reconstruction after injury (a-c). Post-operative (d) and final follow-up radiographs (e)

Surgical approach and implants

For patients with Pipkin II fracture, the modified Gibson approach was performed and the surgical dislocation of the hip was made through the trochanteric flip osteotomy as described by Ganz. The greater trochanter was osteotomized with a step osteotomy, as a variant of the technique originally described, to facilitate repositioning of the trochanter and its definitive fixation.

Fixation of the femoral head fragments was performed using three titanium 3 mm Herbert screws (HCS DePuy-Synthes). The greater trochanter was then repositioned and stabilized through three steel 3.5 mm screws (Fig. 3a-g). For the patient with a fracture of the femoral head and posterior wall of the left acetabulum (Pipkin IV), Gibson approach in lateral decubitus was chosen, and the fixation of the acetabular fracture was obtained through an 8-hole titanium plate with four screws, plus two free lag screws to obtain a more stable fixation of the posterior fragment (PRO Pelvis and Acetabulum System - Stryker).

a-g Shows the steps of performing a safe surgical dislocation with a Ganz osteotomy for ORIF of a Pipkin type I and IV femoral head fracture: a Identified landmarks and planned incision. b Z shaped trochanteric osteotomy. c Z shaped Capsulotomy. d Exposed fracture of femoral head. e Fracture reduction with Weber clamps. f The fracture was reduced and then fixed with cannulated screws. g Reduction and synthesis of the greater trochanter

Post-operative protocol

An x-ray was performed the first day after the operation and all patients underwent the same post-operatory protocol. Thrombosis prophylaxis was achieved with low molecular weight heparin, elastic stockings and early bed mobilization. The patients were allowed to walk without weight bearing after 5 days. For 2 months, patients were treated with physical therapy with minimal weight bearing. Three months after surgery, full weight bearing was allowed.

Clinical and radiological follow-up was planned at first after 2 and 4 weeks, and was then repeated after 3, 6 and 12 months. After the first year, check up occurred every 12 months. Clinical outcome was evaluated according to Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) [12], Vail Hip score (VHS) [13], modified Harris Hip score (mHHS) [14] and Merle D’Aubignè Postel score (MdA) [15]. These clinical scores consider the daily activities of the patients and their discomfort due to pain and functional limitations. WOMAC score has three different subscales: pain, stiffness and physical condition. The higher is the sum of points, the worse is the clinical outcome, with 0-20 range for Pain, 0-8 for Stiffness, and 0-68 for Physical Function. Vail hip score is a self-report scale of patient condition, including pain, daily activities limitation and gait, instead modified Harris Hip score takes into account also the range of motion of the hip. Both of them have 100 as maximum sum of points, but in mHHS the higher the score, the better is the outcome for the patient, as opposed to VHS. MdA score evaluates pain, gait and mobility of the patients, and a higher score in this test means a positive clinical outcome.

Radiographic assessment was made on plain anterior-posterior, obturator oblique and iliac oblique radiographs of the pelvis through Epstein-Thompson classification [16] and Brooker classification for heterotopic ossifications [17].

Results

The mean follow-up was 24 months. Considering scores of the last follow-up visit average Harris modified hip score was 92.1 points (range 75.9–100), and the average Vail score was 81.8 (range 55-95). WOMAC score assessed through pain (A), stiffness (B) and physical condition (C), was: 1.4 A (range 0-7), 1.2 B (range 0-6) and 6.4 C (range 0-22). Merle d’Aubignè Postel score resulted excellent for four patients and good for one patient (Table 2). The complete range of motion was reached at the third month of follow-up. At the last follow-up, fractures were invisible on plain radiographs. According to Epstein-Thompson score of the radiological outcome, four patients showed a good result and one a fair result. No signs of post-traumatic osteoarthritis were observed during follow-up, compared to the contralateral side. No mechanical or infective complications occurred in the five patients. One patient developed heterotopic ossification after surgery (Brooker II) without clinical consequences.

Discussion

Femoral head fractures are commonly associated with high-energy trauma in young patients and in particular with dashboard injuries in car accidents. Thus, patients with Pipkin fractures often arrive in the emergency room as polytrauma. Posterior dislocations of the hip are associated to Pipkin fractures in 4 to 17% of cases [18] and prompt closed reduction in the emergency room is mandatory to prevent avascular necrosis of the femoral head [19]. Conservative treatment is an option for not-displaced fracture or small infrafoveal fragments, even if they are a rare occurrence. Complications associated with long immobility can occur in patients treated conservatively [20]. In order to decide which kind of surgical indication fits most, main factors such as fracture type, comorbidity and the age of the patient, should be considered. Usually, for young patients ORIF is the best option instead of fragment excision [21]. The latter is mostly performed when the fragment is small and there is no involvement of the bearing surface, such as Pipkin I. Instead, total hip arthroplasty is more suitable for elderly patients with an associated femoral neck fracture (Pipkin III), allowing them to start walking sooner, with lower complications rate. According to literature, Pipkin III fractures treated with Total hip replacement (THR) have a better outcome than those treated with ORIF, requiring a THR after failure of the internal fixation [22,23,24]. In elderly patients with fractures of both acetabulum and femoral head (Pipkin IV), fixation and total hip replacement represent a valid and definitive surgical option [25]. The most common surgical approaches for this type of fracture are two: anterior, Smith-Petersen/Hueter, and posterior, Kocher-Langenbeck (K-L). Neither of these approaches allows the surgeon a direct view and proper hip exposure [26]. In 2001, Ganz and his colleagues developed a different surgical technique [10], to allow a complete exposure of the hip and femoral head through digastric flip osteotomy of the greater trochanter. Since then, clinical trials evaluated this new approach showing positive results. Trikha et al. in 2018 [27] reported lower rates of complications in patients with acetabular or femoral head fractures treated through flip trochanter osteotomy, with good clinical outcomes. In his article, mean MdA score showed overall good to excellent result in 87.5% of cases. Lin et al. [28] reached similar results using the same technique, and the total rate of excellent and good outcomes was 77.3% in 22 patients with Pipkin I or II fractures, evaluated through MdA for clinical outcome and Thompson-Epstein for radiological outcome. Mostafa et al. in 2014 [29] had a higher rate of post-operative complications, especially HO and non-union of the osteotomy in the 11 patients with Pipkin I or II fractures treated according to Ganz technique, as compared with our group of patients. In this case the advantage of our study was the use of a “Z-shaped” osteotomy of great trochanter, which allowed a better and more stable reduction of the trochanter.

Even if femoral head fracture is a rare occurrence, our study reports a number of patients similar to case series already published, and therefore it further confirms and strengthens the positive conclusions recorded in Literature about flip trochanter osteotomy in the treatment of femoral head fractures.

As already said, these fractures are very rare, and even if our hospital is one of the largest trauma centers in Italy, the number of patients with a diagnosis of femoral head fracture is too small to provide statistical analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of the Ganz approach. The other limitation of our study is the lack of a control group of patients treated with a different surgical approach.

Conclusions

Gibson’s approach and surgical hip dislocation through Ganz trochanteric flip osteotomy allow a good exposure of the femoral head and acetabulum, giving us the possibility to perform an anatomical reduction of the fracture. Our preliminary experience with this surgical technique, for femoral head fractures, seems to be encouraging. In our case series, satisfactory clinical and radiological short-term results were obtained without significant complications. Further and larger studies are needed to better understand the best treatment option for Pipkin fractures, with a longer follow-up for a better evaluation of clinical and radiological outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ORIF:

-

Open reduction and internal fixation

- AO:

-

Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CHP:

-

Combined hip procedure

- THR:

-

Total hip replacement

- WOMAC:

-

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index

- VHS:

-

Vail Hip score

- mHHS:

-

Modified Harris Hip score

- MdA:

-

Merle d’Aubignè Postel score

- K-L:

-

Kocher-Langenbeck

References

Sahin V, Karakaş ES, Aksu S, Atlihan D, Turk CY, Halici M. Traumatic dislocation and fracture-dislocation of the hip: a long-term follow-up study. J Trauma. 2003;54(3):520–9.

Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium - 2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10 Suppl):S1–S133.

Pipkin G. Treatment of grade IV fracture-dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1957;39-A(5):1027–42.

Romeo NM, Firoozabadi R. Classifications in brief: the Pipkin classification of femoral head fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476(5):1114–9.

Lang-Stevenson A, Getty CJ. The Pipkin fracture-dislocation of the hip. Injury. 1987;18(4):264–9.

Gautier E, Ganz K, Krügel N, Gill TJ, Ganz R. Anatomy of the medial femoral circumflex artery and surgical implications. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82-B:679–83.

Moed BR. The modified Gibson posterior surgical approach to the acetabulum. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(5):315–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181c4aef8.

Swiontkowski MF, Thorpe M, Seiler JG, Hansen ST. Operative management of displaced femoral head fractures: case-matched comparison of anterior versus posterior approaches for Pipkin I and Pipkin II fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1992;6(4):437–42.

Notzli HP, Siebenrock KA, Hempfing A, Ramseier LE, Ganz R. Perfusion of the femoral head during surgical dislocation of the hip: monitoring by laser Doppler flowmetry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:300–4.

De Mauro D, Rovere G, Smimmo A, Meschini C, Mocini F, Maccauro G, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: management of patients affected by SARS-CoV-2 in Rome COVID Hospital 2 Trauma Centre and safety of our surgical team. Int Orthop. 2020;44(12):2487–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04715-6.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–40.

Briggs K, Philippon M. The use of outcome measures in hip arthroscopy. Presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society for Hip Arthroscopy, New York. 2009.

Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–55.

Matta JM, Mehne DK, Roffi R. Fractures of the acetabulum. Early results of a prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;(205):241–50.

Thompson VP, Epstein HC. Traumatic dislocation of the hip: a survey of two hundred and four cases covering a period of twentyone years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1951;33-A:746–78.

Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, Riley LH Jr. Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement. Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1629–32.

Henle P, Kloen P, Siebenrock KA. Femoral head injuries: which treatment strategy can be recommended? Injury. 2007;38(4):478–88.

Giannoudis PV, Kontakis G, Christoforakis Z, Akula M, Tosounidis T, Koutras C. Management, complications and clinical results of femoral head fractures. Injury. 2009;40:1245–51.

Beebe MJ, Bauer JM, Mir HR. Treatment of hip dislocations and associated injuries: current state of care. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47:527–49.

Ross JR, Gardner MJ. Femoral head fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskel Med. 2012;5(3):199–205.

Oransky M, Martinelli N, Sanzarello I, Papapietro N. Fractures of the femoral head: a long-term follow-up study. Musculoskelet Surg. 2012;96(2):95–9.

Stannard JP, Harris HW, Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Functional outcome of patients with femoral head fractures associated with hip dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(377):44–56.

Yu X, Pang QJ, Chen XJ. Clinical results of femoral head fracture-dislocation treated according to the Pipkin classification. Pak J Med Sci. 2017;33:650–3.

Schiedel F, Rieger H, Joosten U, Meffert R. Wenn die Hüfte nicht “nur” luxiert: funktionelle Spätergebnisse nach Hüftkopffrakturen [Not “only” a dislocation of the hip: functional late outcome femoral head fractures]. Unfallchirurg. 2006;109(7):538–44.

Massè A, Aprato A, Alluto C, et al. Surgical hip dislocation is a reliable approach for treatment of femoral head fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3744–51.

Trikha V, Das S, Madegowda A, Agrawal P. Midterm results of trochanteric flip osteotomy technique for management of fractures around the hip. Hip Int. 2018;28(2):148–55. https://doi.org/10.5301/hipint.5000539.

Lin S, Tian Q, Liu Y, Shao Z, Yang S. Mid- and long-term clinical effects of trochanteric flip osteotomy for treatment of Pipkin I and II femoral head fractures. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2013;33(9):1260–4.

Mostafa MF, El-Adl W, El-Sayed MA. Operative treatment of displaced Pipkin type I and II femoral head fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(5):637–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-014-1960-5.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Franziska M. Lohmeyer, PhD, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, for her support revising our manuscript.

Publication costs are funded by Orthopedic and Traumatology School of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore – Roma.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders Volume 22 Supplement 2 2021: All about the hip. The full contents of the supplement are available at https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-22-supplement-2.

Funding

Research fund of Orthopedic and Traumatology School of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore – Roma. The funders did not play any role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DDM and GR designed the study. AS, SM, GC and AP collected the data and interviewed the patients. FL is the senior surgeon who performed the surgery and revise the manuscript. CB and OEE provided data analysis. The authors contributed equally to the writing of the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in the current study were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. As this retrospective analysis consists of anonymized clinical routine data. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Orthopedic school council provided authorization for this study.

Consent for publication

All patients signed an appropriate release to use their health and sensitive data and to be enrolled in the study. Written consent to publish this information was obtained from study participants.

Competing interests

All authors have disclosed potential conflict of interests related to the publication of this manuscript. The authors declare also no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

De Mauro, D., Rovere, G., Smakaj, A. et al. Gibson approach and surgical hip dislocation according to Ganz in the treatment of femoral head fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22 (Suppl 2), 961 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04800-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04800-w