Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common condition that is often associated with chronic pain. Pain often leads patients to seek healthcare advice and treatment. In this retrospective cohort analysis of German longitudinal healthcare claims data, we aimed to explore the healthcare resource utilisation (HRU) and related healthcare costs for patients with OA who develop chronic pain.

Methods

Patient-level data was extracted from the German Institut für Angewandte Gesundheitsforschung (InGef) database. Insured persons (≥18 years) were indexed between January 2015 and December 2017 with a recent (none in the last 2 years) diagnosis of OA. HRU and costs were compared between patients categorised as with (identified via diagnosis or opioid prescription) and without chronic pain. Unweighted HRU (outpatient physician contacts, hospitalisations, prescriptions for physical therapy or psychotherapy, and incapacity to work) and healthcare costs (medication, medical aid/remedy, psychotherapy, inpatient and outpatient and sick pay in Euros [quartile 1, quartile 3]) were calculated per patient for the year following index. Due to potential demographic and comorbidity differences between the groups, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to estimate weighted costs and rate ratio (RR; 95% confidence interval) of HRU by negative binomial regression modelling.

Results

Of 4,932,543 individuals sampled, 238,306 patients with OA were included in the analysis: 80,055 (34%) categorised as having chronic pain (24,463 via opioid prescription) and 158,251 (66%) categorised as not having chronic pain. The chronic pain cohort was slightly older, more likely to be female, and had more comorbidities. During the year following index, unweighted and IPTW-weighted HRU risk and healthcare costs were higher in patients with chronic pain vs those without for all categories. This led to a substantially higher total annual healthcare cost ─ observed mean; €6801 (1439, 8153) vs €3682 (791, 3787); estimated RR = 1.51 (1.36, 1.66).

Conclusions

German patients with chronic pain and OA have higher healthcare costs and HRU than those with OA alone. Our findings suggest the need for better prevention and treatment of OA in order to reduce the incidence of chronic pain, and the resultant increase in disease burden experienced by patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common, chronic condition, primarily characterised by joint pain and impaired function that can lead to decreased quality of life for patients. The World Health Organization places OA among the top 10 most disabling diseases in developed countries, with 80% of patients experiencing limitations in movement and 25% left unable to perform their major daily activities [1]. Worldwide, OA is the most prevalent chronic joint disease, estimated to be symptomatic in around 10% of men and 18% of women aged ≥60 years [1, 2]. A 2014 study of German claims data suggested that the prevalence of hip and knee OA was 22% in patients aged ≥60 years (70% of patients were female) [3]. OA is often described as a disease of ‘wear and tear’; as populations around the world grow older and some present with increased obesity, the number of people affected by OA is likely to rise [2, 4, 5]. Despite age being a strong risk factor for OA, many working age patients are also affected ─ more than half of patients with symptomatic knee OA were aged < 65 years in the 2007/8 United States National Health Interview Survey [5]. Early disease is typically associated with comparatively minor functional impairment that may increase over time. A major determinant of functional disability is pain. In late- and end-stage OA, significant functional impairment is often seen in patients with chronic, persistent pain; however, pain is not exclusively attributable to disease progression or structural joint damage, as determined by imaging [6, 7].

Besides non-pharmacological therapies and patient-centred care (considering each patient’s comorbidity profile, goals, expectations, clinical, emotional, and environmental factors, etc.), most patients with OA receive pharmacological therapies. Recommendations for pharmacological therapies in international treatment guidelines for hip and knee OA have subtly evolved over time, generally moving away from paracetamol (acetaminophen) and more clearly defining the situations where opioids might be appropriate [8,9,10,11,12]. This is also the case in German treatment guidelines [13,14,15]. Joint replacement is generally considered when pain and structural damage becomes intolerably limiting for a patient and cannot be effectively addressed by other therapies [13, 14, 16,17,18]. In Germany, intolerable pain, loss of function, and structural joint damage evident on radiographs form the indications for joint replacement surgery [13,14,15, 18]. Yet, invasive joint surgery has inevitable risks and drawbacks, and is not appropriate for all patients, since for some, surgery involves lengthy recovery or can be associated with a risk of persistent post-surgical pain (~ 9% after hip replacement and 20% after knee replacement) [19]. Additionally, although the majority of modern replacement hips and knees have been found to last at least 25 years [20, 21], revision surgery may be required during the lifespan of the patient. Early and effective treatment of OA can contribute to a delay in, or in some cases even prevent, the need for joint replacement.

To date, the incremental socioeconomic burden of chronic pain caused by OA in Germany has not been established. This study used German longitudinal healthcare claims data to quantify the healthcare resource utilisation (HRU) and associated healthcare costs of chronic pain due to OA. The overarching findings from this study are likely generalisable to other countries with similar healthcare systems and demonstrate the substantial costs involved in the attempt to treat patients with OA and chronic pain.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study based on anonymised claims data from the Institut für Angewandte Gesundheitsforschung (InGef) database. This database contains treatment and diagnosis data for more than 4 million insured persons in Germany, stratified by age and gender (as reported by DESTATIS [The Federal Statistics Office]) to ensure adequate representativeness of the German population.

Patients ≥18 years of age were indexed on main or secondary hospital or assured ambulatory diagnosis of hip or knee OA (per International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition, German modification [ICD-10-GM] codes M16 [hip] and M17 [knee]) between 01 January 2015 and 31 December 2017 (Fig. 1). Patients must not have had an OA diagnosis in the 2 years prior and must have been continuously enrolled in Statutory Health Insurance from January 2013 to December 2018 (or date of death), allowing for a 2-year baseline period and 1-year follow-up period from the index quarter.

Patients within the study population with chronic pain during the follow-up period were identified by a main or secondary hospital diagnosis of chronic pain (ICD-10-GM codes R52.1, R52.2, F45.41, F62.80), an assured ambulatory diagnoses of chronic pain in at least 2 quarters, or ≥ 1 prescription for a weak or strong opioid (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System [ATC] codes N02AA01, 02, 03, 05, 08, 25, 51, 55, 58, 59, 64, 65, 66, 69, 79, N02AB02, 03, 52, 72, N02AF02, N02AG01, 03, N02AJ01, N02AX01, 02, 05, 51, 52, 62; Fig. 1). These patients were categorised as ‘with chronic pain’. All other patients were categorised as being ‘without chronic pain’.

HRU and healthcare costs were compared over the follow-up period for patients categorised as with and without chronic pain. The HRU outcomes were hospitalisations, outpatient physician contacts, incapacity to work, and prescriptions for physical therapy and psychotherapy (Supplementary Table 1, Additional file 1 provides outcome definitions). Model-based estimates of HRU were obtained using negative binomial regression with inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). Healthcare costs were inpatient and outpatient costs, costs for medications, costs for medical aids and remedies, psychotherapy, and sick pay (see Supplementary Table 1, Additional file 1 for definitions). Total costs per patient over the follow-up period were also calculated. All costs were calculated in Euros and modelled on a log scale using linear regression with IPTW to enable relative cost comparisons. Model-implied costs are presented on the original scale.

IPTW was used to adjust for differences in demographics or morbidity profiles in patients categorised as being with and without chronic pain. Weightings were derived from a logistic regression model predicting the probability of being classified as a patient with chronic pain using the following independent variables: type of OA, top 30 most prevalent comorbidities, age, sex, and top 30 most prescribed substances excluding pain medications. The logistic regression coefficients for all variables are shown in Supplementary Table 2, Additional file 2. The distribution of the resulting propensity scores are shown in Supplementary Table 3, Additional file 3; and Supplementary Fig. 1, Additional file 4.

The following formulas were used to calculate the IPTW, where s represents the propensity score of the patient, and p(pain) represents the proportion of patients with chronic pain (i.e. the intercept of a logistic regression model without any covariates).

Patients categorised as with chronic pain:

Patients categorised as being without chronic pain:

The distribution of IPTW was truncated using the 99th percentile as a cut-off point. Based on the accordingly weighted population, logistic regression models were used to estimate the effect of chronic pain on the HRU and cost outcomes, respectively. Rate ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for HRU outcomes.

This study is based on data from the anonymised InGef database and publication was approved by InGef. All analyses were conducted by Elsevier Health Analytics at the Institute for Applied Health Research, Berlin, Germany (InGef). The study was conducted in accordance with all legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value, and rigour.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of 4,932,543 individuals in the sample, 238,306 patients with OA met the inclusion criteria for the study (Fig. 1). One-third of included patients (34%) were categorised as having chronic pain during the follow-up year (either via diagnosis or opioid use). Within this category, 31% of patients (24,463) received an opioid prescription during follow-up, with 0.1% being diagnosed as opioid dependent at index ─ this proportion did not change over follow-up.

Patient selection. aInternational Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition, German modification (ICD-10-GM) code M16* (hips) or M17* (knee). bICD-10-GM R52.1, R52.2, F45.41, or F62.80. cAnatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) code N02AA01, 02, 03, 05, 08, 25, 51, 55, 58, 59, 64, 65, 66, 69, 79, N02AB02, 03, 52, 72, N02AF02, N02AG01, 03, N02AJ01, N02AX01, 02, 05, 51, 52, 62. OA Osteoarthritis

The mean age of all included patients was 64.2 years (standard deviation 13.8 years). As shown in Table 1, there were small demographic differences in the patients categorised as with and without chronic pain. Those with chronic pain appeared to be slightly older and more likely to be female.

Patients categorised as having chronic pain appeared to show a generally higher prevalence of pre-specified comorbidities (Table 2). Within each category, the proportion of patients with pre-specified comorbidities was broadly similar during the 2-year baseline and 1-year follow-up. A table of most commonly prescribed medicine classes at baseline and during the last quarter of follow-up is shown in Supplementary Table 4, Additional file 5.

Healthcare resource utilisation

The observed incidence of healthcare resource utilisation during follow-up for patients with and without chronic pain is shown in Table 3. Patients categorised as having chronic pain had a substantially higher risk of needing every type of healthcare resource studied, as predicted using negative binomial regression modelling with IPTW. The RRs for hospitalisation, incapacity to work, outpatient contacts, and prescriptions for physical therapy and psychotherapy are shown in Supplementary Table 5, Additional file 6.

Healthcare costs

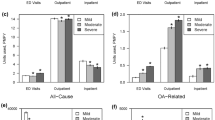

Total observed healthcare cost over the follow-up year in mean Euros (quartile [Q]1, Q3) were 6801 (1439, 8153) for patients categorised as with chronic pain, compared with 3682 (791, 3787) for patients without chronic pain; representing an 85% increase in total cost for patients categorised as having chronic pain. Patients with chronic pain had higher observed mean healthcare costs in all categories (Fig. 2). Hospitalisations (inpatient and outpatient) accounted for the majority of observed mean costs in both groups. Log-linear regression-based estimates for mean healthcare costs by category are shown in Fig. 3. A patient with OA and chronic pain was estimated to have 1.51 times (95% CI: 1.36, 1.66) the healthcare costs of a patient without chronic pain.

Discussion

OA is prevalent in the German population and is more common as age increases [3]. It is a chronic condition, often associated with debilitating pain. This pain can place great strain on a patient’s life and also contributes towards the substantial overall socioeconomic impact of OA [22]. The specific cost burden of treating patients with OA and chronic pain has not yet been determined. Here we demonstrate that this treatment represents a substantial socioeconomic burden for the German healthcare system.

Using claims data from the German InGef database, we show that patients with OA and chronic pain have a higher observed utilisation of all notable healthcare resources and about 85% extra cost in the year following OA diagnosis compared with patients with OA but without chronic pain. However, our population of patients categorised as with chronic pain was slightly older and had a higher comorbidity burden than those without. To address this, we specified generalised linear models with IPTW to adjust for different demographic or comorbidity profiles. Comparable findings arose from this model, again showing a substantially higher risk of hospitalisation, outpatient physician contact, incapacity to work, and prescriptions for physical therapy and psychotherapy during the year following OA diagnosis in patients categorised as with chronic pain as compared with those without. Furthermore, an average patient with OA and chronic pain was estimated to have ~ 1.5 times higher overall annual healthcare costs in the year following OA diagnosis than a patient with OA not complicated by chronic pain. This is slightly lower than the 85% increase seen for the observed costs, probably due to the removal of bias by the model.

In this study, we defined patients as having chronic pain if they had a chronic pain diagnosis or an opioid prescription during follow-up. Data on the use of opioids in the treatment of OA pain in Germany are scarce but a 2019 meta-analysis suggested that the background prevalence of opioid prescription ranges from < 1% to ~ 6% [23]. A paper included in this meta-analysis found OA to be one of the most common diagnoses treated with opioids, and that 8.5% of weak opioid prescriptions in 2010 were for the treatment of knee OA [24]. Our findings suggest that ~ 10% of patients with painful OA received an opioid prescription in the year following diagnosis. This corresponds well with findings from a recent European survey, which found 10.6% of German patients use an opioid for the treatment of OA pain, often long term, but with poor adherence [25].

International guidelines for the non-surgical treatment of hip and knee OA have been subtly evolving over time ─ generally moving away from paracetamol and more clearly defining the situations where opioid use is appropriate [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Furthermore, guidelines increasingly recognise the need to consider comorbidities when selecting pharmacological therapy, and also to incorporate non-pharmacological therapies such as arthritis education, exercise programs, and dietary weight management [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. The updated 2019 Osteoarthritis Research Society International guidelines build on previous editions by developing patient-focused treatment recommendations for individuals with knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis [8, 9]. Aiming to encourage individualised treatment decision-making, the guidelines provide treatment algorithms for patients with a range of common comorbidity combinations [8]. Within these, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are not recommended for patients with cardiovascular comorbidities or frailty. Furthermore, oral or transdermal opioids are strongly recommended against for all patients with OA based on strong evidence showing a lack of efficacy and the potential risk of chemical dependency. German guidelines on the treatment of hip and knee OA recommend opioid therapy for short durations only; for example, as bridging therapy prior to joint replacement surgery [13, 14]. The German guidelines on the long-term use of opioids in non-cancer pain suggest that use in OA should be limited to situations where joint replacement surgery is not possible/not wanted and where other pharmacological/non-pharmacological therapies are unsuitable/ineffective [15]. Together, these guidelines suggest that there are limited situations where opioids are recommended for the treatment of OA; however, our findings demonstrate that a significant proportion of patients with OA are receiving opioid prescriptions in Germany.

It is clear from our findings that chronic pain is associated with substantial extra disease burden in patients with OA. While several papers have previously evaluated the cost of OA in patients taking opioids [26, 27], and we note a recent study additionally reporting on HRU and costs in patients with OA by pain severity episodes [28], we believe that our study uniquely assesses the additional burden of chronic pain as defined by opioid use or diagnosis. As the first assessment of the cost burden of chronic pain in German patients, this study provides a useful estimate of the extra cost burden of chronic pain. This study used claims data from Germany, but our findings are likely to be generalisable to other Western countries with comparable public healthcare systems.

Limitations

The use of claims data has some inherent limitations. We acknowledge that there is potential selection bias in the InGef database, as it does not cover ~ 10% of the German population who use private medical insurance. However, the InGef database is stratified by age and gender, making it more representative of the German population and to which generalisability has been demonstrated [29]. Additionally, while our weighted model was designed to take many demographic and comorbidity factors into account, a residual amount of effect bias may remain – for example, if chronic pain is linked to more severe OA. Subtle changes in the construction of case weights (e.g. by considering those substances with the highest mean cost per patient rather than the most frequently prescribed substances) may also alter the reported HRU and cost estimates, but alternative model specifications were not explored. Furthermore, any statistical adjustment made to our findings may incur collider bias, where an outcome is influenced by more than one variable i.e. HRU and costs are necessarily defined by direct and indirect components. As in all analyses of claims data, it is a limitation that we were unable to causally link diagnoses and prescriptions, therefore, we are unable to be sure if all patients with chronic pain were captured, or if perhaps some patients were taking opioids to address pain related to a comorbidity. Accordingly, our method to identify patients with chronic pain was likely robust but not guaranteed to be free of measurement bias. Furthermore, measurement bias may arise from inaccurately coding the database.

Our use of claims data means that we cannot determine the indication for which each drug was selected. It also means that non-prescription drug use was not captured, including over-the-counter medication, traditional medicines, and lifestyle adaptations. A representative survey of German patients with OA in 2014 noted significant use (~ 80%) of self-paid services, suggesting that a significant proportion of OA treatment might not be captured in claims data [30]. How much of this is related to pain is unknown; while opioid analgesic treatments are very unlikely to be used without clinical supervision, patients might still be using available over-the-counter medication to treat their pain. Because of the structure of the data, this study could not evaluate personal ‘costs’ of advanced OA, such as a reduction in quality of life and effects on mental health.

Conclusions

The burden of disease in patients with OA is substantially higher in those who also experience chronic pain. This burden was visible as higher HRU across hospitalisations, outpatient physician contacts, incapacity to work, and prescriptions for physical therapy or psychotherapy, and also as higher associated healthcare costs. To reduce the burden of disease for the individual and for society, new ways to optimise the prevention and treatment of chronic pain in OA are required.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from InGef but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of InGef.

Abbreviations

- ATC:

-

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HRU:

-

Healthcare resource utilisation

- ICD-10-GM:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition, German modification

- InGef:

-

Institut für Angewandte Gesundheitsforschung

- IPTW:

-

Inverse probability of treatment weighting

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- Q:

-

Quartile

- RR:

-

Rate ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- yr:

-

Year

References

World Health Organization. Chronic diseases and health promotion: chronic rheumatic conditions. https://www.who.int/chp/topics/rheumatic/en/. Accessed 29 Apr 2020.

Bijlsma JW, Berenbaum F, Lafeber FP. Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2115–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60243-2.

Postler A, Ramos AL, Goronzy J, Günther K-P, Lange T, Schmitt J, et al. Prevalence and treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis in people aged 60 years or older in Germany: an analysis based on health insurance claims data. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:2339–49. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S174741.

Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):355–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001.

Deshpande BR, Katz JN, Solomon DH, Yelin EH, Hunter DJ, Messier SP, et al. Number of persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US: impact of race and ethnicity, age, sex, and obesity. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(12):1743–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22897.

Roos EM, Arden NK. Strategies for the prevention of knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(2):92–101. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2015.135.

Rice D, McNair P, Huysmans E, Letzen J, Finan P. Best evidence rehabilitation for chronic pain part 5: osteoarthritis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(11):1769. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8111769.

Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(11):1578–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011.

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(3):363–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003.

Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(2):220–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41142.

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(4):465–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21596.

Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden N, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16(2):137–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013.

Stöve J. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Orthopädie und Orthopädische Chirurgie (DGOOC). 2018. S2k Leitlinie Gonarthrose. AWMF-Registernummer: 033–004. https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/033-004.html. Accessed 4 May 2020.

Matziolis G. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Orthopädie und Orthopädische Chirurgie (DGOOC) 2019. S2k Leitlinie Koxarthrose. AWMF-Registernummer: 033–001. https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/033-001.html. Accessed 4 May 2020.

Häuser W, Bock F, Hüppe M, Nothacker M, Norda H, Radbruch L, et al. Recommendations of the second update of the LONTS guidelines: long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain. Schmerz. 2020;34(3):204–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-020-00472-y.

Quinn RH, Murray JN, Pezold R, Sevarino KS. Surgical management of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26(9):e191–3. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00424.

Gademan MG, Hofstede SN, Vliet Vlieland TP, Nelissen RG, Marang-van de Mheen PJ. Indication criteria for total hip or knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis: a state-of-the-science overview. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1):463. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1325-z.

Lützner J, Lange T, Schmitt J, Kopkow C, Aringer M, Böhle E, et al. The S2k guideline: indications for knee endoprosthesis: evidence and consent-based indications for total knee arthroplasty. Orthopade. 2018;47(9):777–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-018-3612-x.

Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000435. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435.

Evans JT, Walker RW, Evans JP, Blom AW, Sayers A, Whitehouse MR. How long does a knee replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2019;393(10172):655–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32531-5.

Evans JT, Evans JP, Walker RW, Blom AW, Whitehouse MR, Sayers A. How long does a hip replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2019;393(10172):647–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31665-9.

Neogi T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21(9):1145–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2013.03.018.

Rosner B, Neicun J, Yang JC, Roman-Urrestarazu A. Opioid prescription patterns in Germany and the global opioid epidemic: systematic review of available evidence. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221153. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221153.

Werber A, Marschall U, L'Hoest H, Hauser W, Moradi B, Schiltenwolf M. Opioid therapy in the treatment of chronic pain conditions in Germany. Pain Physician. 2015;18(3):E323–31.

Kingsbury SR, Gross HJ, Isherwood G, Conaghan PG. Osteoarthritis in Europe: impact on health status, work productivity and use of pharmacotherapies in five European countries. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(5):937–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket463.

Sicras-Mainar A, Tornero-Tornero C, Vargas-Negrín F, Lizarraga I, Rejas-Gutierrez J. Health outcomes and costs in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic pain treated with opioids in Spain: the OPIOIDS real-world study. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020;12:1759720x20942000. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X20942000.

Jackson J, Iyer R, Mellor J, Wei W. The burden of pain associated with osteoarthritis in the hip or knee from the patient's perspective: a multinational cross-sectional study. Adv Ther. 2020;37(9):3985–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01445-4.

Wei W, Gandhi K, Blauer-Peterson C, Johnson J. Impact of pain severity and opioid use on health care resource utilization and costs among patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(9):957–65. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.9.957.

Andersohn F, Walker J. Characteristics and external validity of the German Health Risk Institute (HRI) database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(1):106–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3895.

Jacobs H, Hoffmann F, Callhoff J, Postler A, Saam J, Zink A, et al. Utilization of individual out-of-pocket health services (IGeL) in persons with osteoarthritis in Germany: results of a survey from the PROCLAIR study. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2019;62(8):1013–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-02986-y.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support was provided by Jennifer Bodkin, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer and Eli Lilly and Company.

A portion of this data has been previously presented at the virtual International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research European Congress in 2020. The published abstract is available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.08.1156.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer and Eli Lilly and Company. Pfizer funded data analysis undertaken at Elsevier Analytics (conducted by authors UVS and SP). MS, UM, and RM are employees at Pfizer. They conducted this study and prepared this manuscript as part of their employment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS and RM designed the study. UVS and SP analysed the data, which was then discussed and interpreted by all authors (MS, UM, UVS, SP, RM). All authors (MS, UM, UVS, SP, RM) contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript, and approved the final version to be submitted. Authors agree to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study analysed anonymised data for which patient consent was not required. The study was conducted in accordance with all legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value, and rigour.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

MS and RM are employees of Pfizer Germany GmbH. UM is an employee of Pfizer Pharma GmbH and holds stock options. UVS and SP are employees of Elsevier Analytics.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.

Definitions for health resource utilisation outcomes and healthcare costs. Definitions used for the assessment of health resource utilisation outcomes and healthcare costs.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 2.

Logistic regression coefficients for variables contributing to the propensity score. Factors incorporated into the logistic regression model to estimate the individual probability of a patient being classified as ‘with chronic pain’. Due to the operational definition of pain in this study, pain medications were excluded from the set of assessed factors. CI 95% confidence interval

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 3.

Propensity score distribution by percentile. Patients in each percentile of the propensity score.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Figure 1.

Propensity score distribution. Percentage of patients with each propensity score.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table 4.

Most frequently prescribed drugs . Top 10 most frequently prescribed drug classes (defined by the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System) for the two years prior to index (baseline) and the last quarter of the follow-up year for patients with osteoarthritis, classified as with and without chronic pain. Defined by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System. yr Year

Additional file 6: Supplementary Table 5.

Estimated healthcare resource utilisation in 2016 based on negative binomial regression with inverse probability of treatment weighting. Conditional means and rate ratios (both with 95% confidence intervals) for healthcare resource utilisation for patients with osteoarthritis, classified as with and without chronic pain in the year following index, estimated using negative binomial regression with inverse probability of treatment weighting. All are per patient-year. *p < 0.001; †p < 0.05 by chi squared with Wald test. 95% CI 95% confidence interval

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schild, M., Müller, U., von Schenck, U. et al. The burden of chronic pain for patients with osteoarthritis in Germany: a retrospective cohort study of claims data. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22, 317 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04180-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04180-1