Abstract

Background

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) include a variety of parenchymal lung diseases. The most common types of ILDs are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), autoimmune ILDs and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP). There is limited real world data on care patterns of patients with chronic fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype other than IPF. Therefore, the aim of this study is to describe care patterns in these patients.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used claims data from 2015 to 2019 from the Optum Research Database. The study population included adults (≥ 18 years old) with at least two diagnosis codes for fibrosing ILD during the identification period (1OCT2016 to 31DEC2018). A claim-based algorithm for disease progression was used to identify patients likely to have a progressive fibrotic phenotype using progression proxies during the identification period. Index date was the first day of progression proxy identification after fibrosing ILD diagnosis. Patients were required to have continuous enrollment for 12 months before (baseline) and after (follow-up) index date. Patients with an IPF diagnosis were excluded. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the patient population and care patterns.

Results

11,204 patients were included in the study. Mean age of the patient population was 72.7 years, and 54.5% were female. Unclassified ILDs (48.0%), HP (25.2%) and autoimmune ILDs (16.0%) were the most common ILD types. Other respiratory conditions were prevalent among patients including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (58.9%), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (25.0%) and pulmonary hypertension (9.8%). During baseline, 65.3% of all patients had at least one pulmonology visit, this proportion was higher during follow-up, at 70.6%. Baseline and follow-up use for HRCT were 39.9% and 48.8%, and for pulmonary function tests were 43.7% and 48.5% respectively. Use of adrenal corticosteroids was higher during follow-up than during baseline (62.5% vs. 58.0%). Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive medication classes were filled by a higher percentage of patients during follow-up than during baseline.

Conclusions

Comprehensive testing is essential for diagnosis of a progressive phenotype condition, but diagnostic tests were underutilized. Patients with this condition frequently were prescribed anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a broad term that describes over 200 diverse lung disorders, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), autoimmune ILD, hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) and sarcoidosis [1]. Typical symptoms of ILD are cough and dyspnoea, as well as decreased lung capacity [2]. IPF is the most common idiopathic ILD and represents the prototype of progressive fibrosing ILD depicted by lung function decline and early mortality [3]. In addition to IPF, 13–40% of patients with other fibrosing ILDs can develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis during their disease course [4]. Chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype, despite manifesting in patients with a variety of underlying conditions, is driven by overlapping pathogenic mechanisms including lung parenchymal injury, TGF-mediated fibroblast activation, and myofibroblast accumulation [5].

There is a lack of consensus among physicians on how to diagnosis and treat patients with chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype [6]. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with a progressive phenotype is complex, often requiring a multi-disciplinary team of physicians, including pulmonologists and rheumatologists [7]. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is the main diagnostic tool for differential diagnosis. Pulmonary function testing (e.g. forced vital capacity (FVC), diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide [DLco]) and tissue biopsy are also used for diagnosis [8].

After diagnosis of a progressive phenotype, patients are usually treated on an empirical basis by using corticosteroids as first-line treatment, often in conjunction with other immunosuppressive medications [9]. Using empirical treatment is a common practice in many developed countries, even though this treatment approach does not have enough clinical evidence in terms of efficacy [10]. In addition, some immunosuppressive medications (e.g. antitumor necrosis factor (TNF) α) may be associated with deteriorating ILD effects [11]. In March 2020, Food Drug Administration approved the first therapeutic agent, nintedanib, for treatment of patients with chronic fibrosing ILDs 12]. Approval of nintedanib could significantly improve the treatment pattern of patients with a progressive phenotype.

With limited evidence on care patterns of patients with chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype, there is a need to better understand care and treatment of this condition. This study will focus on non-IPF patients as the care pattern of IPF was extensively investigated in previous studies. To better understand the real-world treatment patterns in chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype, this study used administrative claims data to investigate the current care patterns in patients with chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype.

Methods

Study design

This study was an observational retrospective cohort study using existing administrative claims data.

Data source

This study used administrative claims data from 2015 to 2019 from the Optum Research Database (ORD). The ORD is geographically diverse across the US and contains deidentified medical and pharmacy claims data and linked enrollment information for individuals enrolled commercial and Medicare Advantage health plans. Medical claims in the ORD include, but are not limited to, dates and place of service (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department visits), diagnoses, procedures, and detailed information on hospitalizations including admission and discharge dates. Pharmacy claims in the ORD include complete outpatient prescription drug information, which includes the costs of mail-order drugs, injectables, drugs from specialty pharmacies, and all standardized prescription-level fields collected on a typical pharmacy claim (e.g., date of fill or refill, drug name and class, strength, quantity, and days supply).

Study population

The study included commercial and Medicare Advantage with Part D (MAPD) health plan enrollees diagnosed with chronic fibrosing ILD and a progressive phenotype proxy from 01 to 2016 through 31 December 2018 (Fig. 1). The index date of this study was the date of a claim for a proxy for the progressive phenotype. Chronic fibrosing ILD was identified for the individuals with at least two medical claims on separate dates, within 30–365 days, with diagnosis codes for lung fibrosis (ICD-10-CM codes: J8410, J8489, J84111, J84113, J8409, J849, and M3481), identification period [13, 14]. As there was not any diagnostic or procedure codes specific to a progressive phenotype during study identification period, this study used previously validated proxies for progressive phenotype identification [13, 14]. In order to identity individuals with a progressive phenotype, the following proxies were used: (1) At least two pulmonary function tests within 90 days of each other; (2) At least two high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans within 360 days of each other; (3) At least three chest computed tomography scans within 360 days of each other; (4) At least two oxygen titration tests within 90 days of each other; (5) At least one claim for oxygen therapy; (6) At least one respiratory hospitalization; (7) At least one claim for palliative care; (8) At least one claim for a lung transplant; (9) At least one new claim for an immunosuppressive medication; (10) At least one claim for oral corticosteroids with a dose greater than 20 mg per day (Additional file 1: Appendix) [13, 14]. The date of first claim was used as the index date for those proxies that required more than one claim for identification.

This study excluded those who were less than 18 years of age at index date. Other exclusions included (1) less than 12 months of continuous enrollment in medical and pharmacy benefits before and after the index date (enrollment gap less than 30 days was allowed); (2) at least one IPF diagnosis claim (ICD-10-CM: J84.112) during study period; (3) more than one insurance type during study period.

Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients were measured at the index date or during the 12-month baseline period, and included age, gender, insurance type, geographic region, and race/ethnicity. Baseline clinical characteristics included Charlson comorbidity score, ILD type, and comorbidities of interest, identified by using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modifications (ICD-10-CM) codes (Additional file 1: Appendix).

Baseline and follow-up patterns of care (i.e. diagnostic tools, specialist visits, and prescribed medications use) were assessed for all patients. As patients with autoimmune ILD (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, polymyositis, systemic sclerosis, and mixed connective tissue disease) may have different types of specialist visits and medications, this study reported these measures separately for this group of patients. Use of HRCT and pulmonary function test were captured by using Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition (CPT-4) codes (Additional file 1: Appendix). Lung biopsy was identified by using ICD-10 Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) (Additional file 1: Appendix). Moreover, pulmonologists and rheumatologist visits were assessed based on the provider specialty category. Use of selected medications were identified by using National Drug Code (NDC) (Additional file 1: Appendix), reported as the percentage of patients with at least one prescription. The most common classes of medication were identified based on Multum level 2 categories. Select classes of medications were (1) oral corticosteroids (OCS) (i.e., prednisone, methylprednisolone, hydrocortisone prednisolone, dexamethasone, cortisone acetate, betamethasone), (2) Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (i.e., rituximab, tocilizumab, abatacept, denosumab, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab), (3) Non-biological DMARDs (i.e., methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, chloroquine phosphate, penicillamine) and (4) Immunomodulators (i.e., cyclosporine, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, sirolimus, cyclophosphamide, everolimus).

Statistical analysis

All study variables were analyzed descriptively. Numbers and percentages were provided for categorical variables; means and standard deviations were provided for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using Instant Health Data (IHD) software (Panalgo, Boston MA, USA) and R, version 3.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study sample

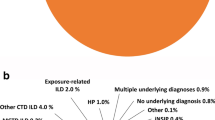

A total of 11,204 patients with chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype met eligibility criteria and were included in the study (Fig. 2). The mean age of the patient population was 72.7 years and 54.5% were female. The majority of the population was Caucasian (68.5%) and had Medicare coverage (84.3%) (Table 1). Unclassified ILDs (48.0%), hypersensitivity pneumonitis (25.2%) and autoimmune ILDs (16.0%) were the most common ILD types. Some common comorbid conditions among this population were hypertension (81.6%), diabetes (37.5%), and heart failure (30.3%). Other respiratory conditions were also prevalent including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (58.9%), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (25.0%), and pulmonary hypertension (9.8%) (Table 1).

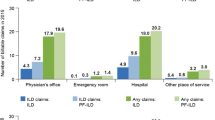

Patterns of care

During baseline, 65.3% of all patients had at least one pulmonology visit, this proportion was higher during follow-up, at 70.6% (Table 2). 42% of patients with an autoimmune condition had at least one pulmonology and one rheumatology visit during baseline, and this proportion was 48.1% during follow-up. Baseline use of diagnostic tests was generally lower than follow-up except for lung biopsy [HRCT (39.9% and 48.8%), pulmonary function tests (43.7% and 48.5%), and lung biopsy (12.7% vs. 9.8%)] (Table 3). The baseline use of the most common class of medications, adrenal cortical steroids, was higher during follow-up for the overall population (58.0% vs. 62.5%) and for those with autoimmune conditions (70.4% vs. 74.7%) (Table 4). Among all patients, the oral corticosteroids class (baseline: 45.8% and follow-up: 60.2%) was the most used anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive medication class. Use of oral corticosteroids was higher among patients with autoimmune conditions (baseline: 58.7% and follow-up: 68.5%). Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive medication classes were filled by a higher percentage of the population during follow-up than during baseline (Table 4). During baseline, 6.9% of patients with an autoimmune condition had at least one prescription of mycophenolate mofetil; this number almost doubled (13.0%) during follow-up. Moreover, the percentage of use of azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, IVIG, rituximab, and tacrolimus increased during follow-up in comparison with the percentage of use during baseline. In contrast, patients with an autoimmune condition used methotrexate and anti-tumor necrosis factor-α with a lower percentage during follow-up compared to baseline (Table 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe real-world care patterns of patients with non-IPF chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype. Our findings illustrated that patients with a progressive phenotype have high multimorbidity burden and high prevalence of other diseases (e.g. diabetes, COPD, OSA). On one hand, these comorbid conditions may affect the progression of fibrosis ILD. For example, diabetes may influence the progression or the onset of a progression through hyperglycemia-associated pulmonary inflammation [15, 16]. On the other hand, a progressive phenotype may increase the risk of comorbidities the same as in patients with IPF. Previous studies among patients with IPF suggested that these patients are at higher risk of heart failure [17], pulmonary hypertension [17, 18], and OSA [19, 20].

Another important finding of this study is that almost 60% of patients with a chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype had a diagnosis of COPD. Moreover, almost half of the included patients in this study had a history of tobacco use. Hence, it is not surprising that patients with a progressive phenotype may also have COPD. It is not certain whether pulmonary fibrosis and COPD are two different diseases associated with tobacco use or if instead they represent a distinctive phenotype of a subset of patients referred to as “combined pulmonary fibrosis emphysema” [21, 22]. Another possibility behind high prevalence of COPD among patients with a progressive phenotype may be related to the misdiagnosis of a progressive phenotype and COPD due to common symptoms (e.g. cough, dyspnoea) [23]. For differentiation between these conditions, the involvement of a pulmonologist in the diagnosis process is crucial.

Two out of three patients with a progressive phenotype had at least one pulmonology visit during baseline. Moreover, this study illustrated that about 71% of patients had at least one pulmonologist visit during follow-up. Pulmonologists play an integral role in diagnosis and management of disease [8]. Expert interviews suggest that pulmonologists are responsible for the diagnosis of this condition [10, 24]. Similarly, a real-world data analysis study in the United States found that almost 75% of patients with ILD visit a pulmonologist at least once a year [10]. For the subset of patients with autoimmune conditions, about 40% patients had both pulmonologist and rheumatologist visits. Currently, the gold standard for the diagnosis of an autoimmune ILD includes the involvement of both pulmonologists and rheumatologists [25, 26]. Patients with mild ILD can be managed solely by rheumatologists, while patients with a progressive phenotype need involvement of pulmonologists [27].

Another finding of this study is that less than half of included patients had HRCT and pulmonary function tests during both baseline and follow-up. These proportions may indicate that both pulmonary function tests and HRCT are underutilized among the patients with a progressive phenotype in the United States. For diagnosis and monitoring of patients with ILDs, using both HRCT and pulmonary function tests are necessary [28]. In a physician survey conducted in United States, Europe, and Japan, common follow-up tests, including pulmonary function tests and HRCT, are suggested every 6 months [10] The main role of HRCT is to identify radiographic patterns that such as usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), organizing pneumonia (OP) and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) [8]. Following lung function testing and clinical workup, identification of radiologic pattern is sufficient to clinically diagnose most types of ILD (e.g., autoimmune-ILD, HP, etc.) even without a lung biopsy [8, 29].

Adrenal cortical steroids, specifically oral corticosteroids, was the most used medication class during the baseline and follow-up period in this study. This class of medications decreases inflammation but can lead to harmful long-term side effects [30]. In the past, oral corticosteroids were the choice medication for treating systemic sclerosis ILD (SSc-ILD), a type of autoimmune ILDs [31]. Although oral corticosteroids have been used for autoimmune ILDs based on clinical experience, there are no controlled clinical trials of these drugs. Because of concerns about the increased risk of scleroderma renal crisis related to the use of high-dose corticosteroids, only low-dose therapy (20 mg daily) with oral corticosteroids are recommended for patients with SSc-ILD [32]. For other types of ILDs with a progressive phenotype, data are even more limited and variable.

Another finding of this study was that patients with a progressive phenotype had higher percentage of using non-biological DMARDs, immunomodulators, and biological DMARDs during follow-up compared to baseline. Furthermore, the percentages of use of mycophenolate mofetil was almost doubled during follow-up compared to baseline for all patients and those with autoimmune condition. For autoimmune ILDs mycophenolate has emerged as the standard treatment [33]. The use of mycophenolate in autoimmune-ILD has been investigated in a number of case reports, retrospective studies, and prospective RCTs [34, 35]. Moreover, this study illustrated that the percentages of methotrexate and anti TNF-alpha agents (e.g. infliximab, adalimumab) use were decreased during follow-up compared to baseline. This reduction of use may be related to the concerns about potential pulmonary toxicity related to the use of anti TNF-alpha and methotrexate among patients with ILD conditions [36].

Limitations

First, the data source did not have any clinical information on symptoms, pulmonary function tests results and imaging findings. Therefore, proxies for progression were used for identification of the progression phenotype based on the literature. Second the last year of available data was 2019. Therefore, this study did not identify the use of nintedanib, the only FDA approved medication for chronic fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype [12]. Third, this study did not capture the severity of diseases, type of lung biopsy, and type of pulmonary function test, due to the nature of administrative claims database. Lastly, this study only included US commercial and Medicare health plan enrollees; therefore, the findings are most applicable to insured US patients and may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusions

This study is the first to characterize care patterns of patients with chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype. The disease complexity of chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype creates significant challenges for clinicians. Moreover, the rarity of this condition limits efforts to conduct more real-world studies to understand care patterns of patients with a progressive phenotype. Comprehensive testing is essential for diagnosis of this condition and diagnostic tests are underutilized for these patients. Accurate diagnosis and treatment require involvement of pulmonologist for all patients with a progressive phenotype which needs attention. For subset of patients with autoimmune conditions a multidisciplinary approach, incorporating rheumatologists and pulmonologists is necessary. Treatment for chronic fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype consists mostly of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents, which is expected to change following the approval of nintedanib with the indication for chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype.

Availability of data and materials

The proprietary data that used in this study are available from Optum Research Database (ORD) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, and so they are not publicly available. Please contact Optum for information on licensing the data.

Abbreviations

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DLco:

-

Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- HP:

-

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- HRCT:

-

High-resolution computed tomography

- ICD-10-CM:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification

- ILD:

-

Interstitial lung disease

- IPF:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SSc-ILD:

-

Systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease

- UIP:

-

Usual interstitial pneumonia

- CPT-4:

-

Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition

- ICD-10-PCS:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Procedure Coding System

- NDC:

-

National Drug Code

References

Goos T, Sadeleer LJD, Yserbyt J, Verleden GM, Vermant M, Verleden SE, et al. Progression in the management of non-idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis interstitial lung diseases, where are we now and where we would like to be. J Clin Med. 2021;10(6):1330.

Podolanczuk AJ, Wong AW, Saito S, Lasky JA, Ryerson CJ, Eickelberg O. Update in interstitial lung disease 2020. Am J Respir Crit Care. 2021;203(11):1343–52.

Cottin V. Treatment of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: a milestone in the management of interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(153):190109.

Olson A, Hartmann N, Patnaik P, Wallace L, Schlenker-Herceg R, Nasser M, et al. Estimation of the prevalence of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: systematic literature review and data from a physician survey. Adv Ther. 2021;38(2):854–67.

Spagnolo P, Distler O, Ryerson CJ, Tzouvelekis A, Lee JS, Bonella F, et al. Mechanisms of progressive fibrosis in connective tissue disease (CTD)-associated interstitial lung diseases (ILDs). Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(2):143–50.

Richeldi L, Varone F, Bergna M, de Andrade J, Falk J, Hallowell R, et al. Pharmacological management of progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: a review of the current evidence. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(150):180074.

Takizawa A, Kamita M, Kondoh Y, Bando M, Kuwana M, Inoue Y. Current monitoring and treatment of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease: a survey of physicians in Japan, the United States, and the European Union. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(2):1–17.

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care. 2012;165(2):277–304.

Maher TM, Wuyts W. Management of fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Adv Ther. 2019;36(7):1518–31.

Wijsenbeek M, Kreuter M, Olson A, Fischer A, Bendstrup E, Wells CD, et al. Progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: current practice in diagnosis and management. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(11):1–10.

Iqbal K, Kelly C. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: a perspective review. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2015;7(6):247–67.

Hamblin MJ, Kaner RJ, Owens GM. The spectrum of progressive fibrosis interstitial lung disease: clinical and managed care considerations. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(Suppl 7):S147-54.

Olson AL, Patnaik P, Hartmann N, Bohn RL, Garry EM, Wallace L. Prevalence and incidence of chronic fibrosing interstitial lung diseases with a progressive phenotype in the United States estimated in a large claims database analysis. Adv Ther. 2021;38(7):4100–14.

Singer D, Bengtson LGS, Conoscenti CS, Laouri M, Shetty SS, Anderson AJ, et al. Claims-based prevalence of disease progression among patients with non-IPF fibrosing interstitial lung disease in the US. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022.

Hunt WR, Zughaier SM, Guentert DE, Shenep MA, Koval M, McCarty NA, et al. Hyperglycemia impedes lung bacterial clearance in a murine model of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Am J Physiol-Lung C. 2014;306(1):L43-9.

Kyung SY, Byun KH, Yoon JY, Kim YJ, Lee SP, Park J-W, et al. Advanced glycation end-products and receptor for advanced glycation end-products expression in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and NSIP. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;7(1):221–8.

Broder M, Change E, Papoyan E, Popescu I, Reddy S, Raimundo K, et al. Risk of cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of Medicare data. 6 1 Epidemiology. 2016;PA4919.

Collard HR, Ward AJ, Lanes S, Hayflinger DC, Rosenberg DM, Hunsche E. Burden of illness in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Med Econ. 2012;15(5):829–35.

Mermigkis C, Bouloukaki I, Schiza SE. Sleep as a new target for improving outcomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2017;152(6):1327–38.

Mermigkis C, Bouloukaki I, Antoniou K, Papadogiannis G, Giannarakis I, Varouchakis G, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea should be treated in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(1):385–91.

Cottin V, Nunes H, Brillet P-Y, Delaval P, Devouassoux G, Tillie-Leblond I, et al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a distinct underrecognised entity. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(4):586–93.

Chilosi M, Poletti V, Rossi A. The pathogenesis of COPD and IPF: distinct horns of the same devil? Respir Res. 2012;13(1):3.

Michaudet C, Malaty J. Chronic cough: evaluation and management. Am Fam Phys. 2017;96(9):575–80.

Fischer A, Wijsenbeek M, Kreuter M, Mounir B, Zouad-Lejour L, Acciai V, et al. SAT0593 progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease (PF-ILD) in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(Suppl 2):1149.

Levi Y, Israeli-Shani L, Kuchuk M, Shochet GE, Koslow M, Shitrit D. Rheumatological assessment is important for interstitial lung disease diagnosis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45(11):1509–14.

Chaudhuri N, Spencer L, Greaves M, Bishop P, Chaturvedi A, Leonard C. A review of the multidisciplinary diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases: a retrospective analysis in a single UK specialist centre. J Clin Med. 2016;5(8):66.

Sambataro D, Sambataro G, Pignataro F, Zanframundo G, Codullo V, Fagone E, et al. Patients with interstitial lung disease secondary to autoimmune diseases: how to recognize them? Diagnostics. 2020;10(4):208.

Makino S. Progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: a new concept and indication of nintedanib. Mod Rheumatol. 2020;31(1):13–9.

Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care. 2018;198(5):e44-68.

Mundell L, Lindemann R, Douglas J. Monitoring long-term oral corticosteroids. BMJ Open Qual. 2017;6(2):e000209.

Yasuoka H. Recent treatments of interstitial lung disease with systemic sclerosis. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2016;9(Suppl 1):97–110.

Mathai SC, Danoff SK. Management of interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue disease. BMJ. 2016;352:h6819.

Hamblin MJ, Kaner RJ, Owens GM. The spectrum of progressive fibrosis interstitial lung disease: clinical and managed care considerations. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(Suppl 7):S147-54.

Baqir M, Makol A, Osborn TG, Bartholmai BJ, Ryu JH. Mycophenolate mofetil for scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease: a real world experience. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0177107.

Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Khanna D, Kleerup EC, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(9):708–19.

Bes C. Comprehensive review of current diagnostic and treatment approaches to interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2019;6(3):146–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author informations

MN is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc. DS and MH were employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc at the time of this study. DS and MH are currently employees of GSK.

Funding

This study was funded by the Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MN wrote the manuscript and contributed to the concept development and analysis. DS contributed to the concept development and edited the manuscript. MH contributed to the analysis and edited the manuscript. The authors meet the criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is not applicable because it is a retrospective study of an existing database. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix.

Codes list.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nili, M., Singer, D. & Hanna, M. Care patterns of patients with chronic fibrosing interstitial lung disease (ILD) with a progressive phenotype. BMC Pulm Med 22, 153 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-01953-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-01953-9