Abstract

Background

Although combination therapy is the gold standard for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), some of these patients are still being treated with monotherapy.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis at four German PH centres to describe the prevalence and characteristics of patients receiving monotherapy.

Results

We identified 131 incident PAH patients, with a mean age of 64 ± 13.8 years and a varying prevalence of comorbidities, cardiovascular risk factors and targeted therapy. As in other studies, the extent of prescribed PAH therapy varied with age and coexisting diseases, and younger, so-called “typical” PAH patients were more commonly treated early with combination therapy (48% at 4–8 months). In contrast, patients with multiple comorbidities or cardiovascular risk factors were more often treated with monotherapy (69% at 4–8 months). Survival at 12 months was not significantly associated with the number of PAH drugs used (single, dual, triple therapy) and was not different between “atypical” and “typical” PAH patients (89% vs. 85%).

Conclusion

Although “atypical” PAH patients with comorbidities or a more advanced age are less aggressively treated with respect to combination therapy, the outcome of monotherapy in these patients appears to be comparable to that of dual or triple therapy in “typical” PAH patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The current international [1] and national (Cologne Consensus Conference, [2]) Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of P(A)H provide a comprehensive overview of supportive, targeted and interventional therapeutic options. It is recommended that targeted PAH therapy be implemented according to the risk profile. For this reason, various findings and parameters are used to categorize patients into three risk groups, consisting of low, intermediate and high estimated one-year mortality. Nevertheless, early combination therapy is the gold standard for most patients with PAH [3], and several meta-analyses support this approach [4,5,6,7,8]. However, the patients included in these studies do not necessarily represent the entire spectrum of patients routinely treated at PH centres and described in PAH registries. For example, patients included in randomized controlled trials tend to be younger and have fewer comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors. Comparative studies of these different patient groups indicate that PAH combination therapy in elderly patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors (so-called “atypical” PAH patients) may be associated with a higher rate of side effects and reduced efficacy [9]. A post hoc analysis of the AMBITION trial confirmed these findings [10]. These data have been considered in the German recommendations (Cologne Consensus Conference, [2]. Hence, these “atypical” patients, when assigned to the low- or intermediate-risk group, might be treated with monotherapy [11]. It remains to be seen whether such an approach will generally be adopted. Accordingly, initial monotherapy was also mentioned in the 6th world symposium as an appropriate treatment option for selected patients [3]. These include older PAH patients (> 75 years) with cardiovascular risk factors for the presence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and patients with portopulmonary hypertension or uncorrected congenital heart defects.

The presented analysis aimed to answer the following questions: (1) what is the proportion of PAH patients treated with monotherapy in daily routine at German PH centres; (2) do PAH patients with comorbidities receive monotherapy more frequently; and (3) do PAH patients receiving monotherapy have poorer outcomes?

Methods

Patients

Out of 782 PH patients treated at four German PH centres between 2016 and 2018, 158 were classified as having PAH. In this group, complete data, including data on comorbidities, cardiovascular risk factors and PAH medications, were available for 131 incident PAH patients, representing the group analysed.

Patients were categorized as having “typical” or “atypical” PAH according to the criteria proposed by the Cologne Consensus Conference [11]. “Atypical” patients were defined as being > 65 years old and having ≥ 3 of the following comorbidities or cardiovascular risk factors: arterial hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2), diastolic dysfunction (by echocardiography) or atrial fibrillation (Table 1).

In addition, a broad spectrum of comorbidities potentially affecting the outcome in these patients were recorded, including chronic kidney disease, thromboembolic disease, peripheral arterial occlusive disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), interstitial lung disease (ILD), cancer and obstructive sleep apnoea.

Data collection

The four contributing university PH centres are considered representative of German PH centres, as they are well-established institutions with documented expertise in diagnosing and treating PH patients. Furthermore, they regularly participate in clinical studies and maintain good collaboration. The number of PH patients treated with monotherapy at these four centres is comparable to data on the German registry (COMPERA registry, data on file).

The following data were collected retrospectively from medical records: age, sex, weight, height, secondary diagnoses, selected echocardiographic parameters, spiroergometric parameters, 6-min walking distance and haemodynamic parameters. The prescribed PAH drugs were documented for the entire observation period, and the vital status (alive, dead, transplanted, lost to follow-up) was recorded at the end of follow-up on September 30, 2019.

Follow-up

Follow-up data were collected at 0—3 months (baseline), 4—8 months (1st follow-up) and 9—15 months (2nd follow-up).

Statistics

Continuous data are presented as the mean (± standard deviation), and categorical variables are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages. The t-test was used to compare selected parameters between patients with “typical” or “atypical” PAH. Categorical variables were compared by the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or the McNemar test. Survival was evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis, and differences between groups were assessed by the log-rank test. Analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Greifswald (Reg. No. BB 167/18, with an amendment to extend the observation period).

Results

The study included 131 patients (49.6% male), of whom 48 (36.6%) were classified as having idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) and 83 (63.4%) were classified as having pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). At baseline, the mean age was 64 ± 13.8 years, and the functional class (FC) was III in 90 (68.7%) and IV in 23 patients (17.6%) (Table 1). The average 6-min walking distance was 266 ± 129 m.

Considering cardiovascular risk factors and age, 86 (65.6%) patients were classified as having “typical” PAH and 45 (34.4%) were classified as having “atypical” PAH. Comparing “typical” and “atypical” PAH patients, significant differences between the two groups were found in terms of age, sex, diastolic dysfunction, arterial hypertension, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and peak oxygen uptake (Table 1).

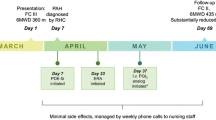

At baseline, 117/131 (89.3%) patients were treated with targeted PAH therapy, with 83 (70.9%) receiving monotherapy, 27 (23.1%) receiving dual therapy and 7 (6.0%) receiving triple therapy. At the first follow-up, 125/131 patients (95%) were treated with PAH therapy, of whom 72 (57.6%) continued to receive monotherapy, while 53 (42.4%) were on dual or triple therapy. At the second follow-up, 111/131 patients (85%) were available, of whom 50 (45.0%) continued to receive monotherapy, while 61 (55.0%) were on dual or triple therapy (Fig. 1). Overall, the median follow-up duration was 22 months (13; 30).

Regarding the “atypical” or “typical” phenotype, we found significant differences in the distribution of monotherapy vs. dual/triple therapy at baseline (p = 0.036), a pattern that persisted, although no longer significant, at the first and second follow-ups (Table 2). In “atypical” patients, we observed an increased proportion of combination therapy over time (baseline to first follow-up, p = 0.014 and to second follow-up, p = 0.002).

With increasing age, the proportion of patients treated with combination therapy decreased. At baseline, older patients received more monotherapy (p = 0.016). This difference was no longer significant at the first or second follow-up (Table 3). However, in patients over 65 years of age, we observed an increased proportion of combination therapy over time (baseline to first follow-up, p < 0.001 and to second follow-up, p < 0.001).

Survival

There was no significant difference (p = 0.411) in survival with respect to the number of PAH drugs prescribed (Fig. 2). Accordingly, at 12 months, survival was similar between patients with “atypical” and “typical” PAH (89% vs. 85%, p = 0.700, Fig. 3). Within the “atypical” PAH group (N = 45), survival at 12 months did not differ between patients on combination therapy and those on monotherapy (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This study enrolled 131 incident PAH patients treated at four German PH centres between 2016 and 2018. The mean patient age of 64 ± 13.8 years is comparable to that of patients in registry studies used for risk assessment [12,13,14] but higher than that in recently published clinical trials [15,16,17,18]. Among recent randomized clinical trials, the mean age was 54 ± 14 years in the AMBITION trial [19], 46 ± 16 years in the SERAPHIN trial [20] and 48 ± 15 years in the GRIPHON trial [21].

Only 36.6% of our patients were classified as having IPAH; however, this number reached up to 75% in clinical trials [12] and ranged between 46 and 63% in PH registries [22, 23]. One reason for this difference might be the high proportion of PAH patients with comorbidities or cardiovascular risk factors. In previous registry studies, such data were not systematically collected [24,25,26]. The English ASPIRE registry reported comorbidities in 37% of their CTEPH patients [27]. For the first time, a more complete analysis of comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors was performed in the American REVEAL registry [23]. In contrast, the COMPERA registry [28] obtained data for only a limited number of comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors, although these investigators pointed out a significant increase in the age of their newly diagnosed IPAH patients. In later studies [19, 29] as well as registry analyses [13, 30], these data were documented more comprehensively. Remarkably, the amendment redefining the eligibility criteria in the recruiting phase of the AMBITION trial to implement more stringent haemodynamic requirements and exclude patients with ≥ 3 risk factors for left ventricular diastolic dysfunction led to a change in the study population [19]. The background of this modification was based on the observation that a relevant proportion of the initially recruited patients had cardiovascular risk factors (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, relevant coronary heart disease). This subgroup of patients was described as having “atypical” PAH to distinguish them from “classical” IPAH patients with few comorbidities [31]. This terminology was adopted in subsequent studies [9] and in the German recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of PH. Certain comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors are more common in our patients than in other cohorts, especially arterial hypertension (Table 4). It remains unclear whether these differences in risk factor and comorbidity profiles are due to variations in data acquisition or represent distinct patient populations [32]. The incidence of echocardiographic signs of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, which is not even reported in most studies or registries, could be documented in almost 50% of our patients, although not all criteria of the most recent definition of “heart failure with preserved ejection fraction” were met [33]. Our findings are in line with those of previous reports describing frequent signs of “left ventricular diastolic dysfunction” in patients with IPAH [34]. Among the other comorbidities, both chronic kidney disease [13, 35] and ischaemic heart disease [13] are prognostically relevant. For this reason, chronic kidney disease is part of the REVEAL risk score [36]. Pulmonary hypertension is a frequent finding in patients with chronic kidney disease [37, 38]. Moreover, with increasing age, the incidence of kidney dysfunction increases in patients with PAH (63% for IPAH patients 65–74 years old, 85% for those ≥ 75 years old) [13]. It is not yet clear whether patients with PH and kidney dysfunction should be categorized in WHO Group V or classified as PAH patients with renal comorbidity [39].

Similar to other chronic diseases, such as chronic heart failure [40] or COPD [41], the prevalence of comorbidities increases with age and affects survival in PAH patients. Therefore, the treatment of these comorbidities can also improve the prognosis of the “primary” disease, in this case, PAH [42]. On the other hand, previous studies have suggested that the clinical response to targeted PAH drugs can be comparable, irrespective of the number of comorbidities [9, 10, 43]. Recent studies using cluster analyses have described different IPAH phenotypes based on age, the presence of cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities and selected echocardiographic, spiroergometric and haemodynamic findings [44], as done previously in patients with pulmonary heart disease [45]. These data suggest that so-called type II pulmonary heart disease, with severe pulmonary vascular involvement and right ventricular dysfunction, is comparable to PAH. A similar approach (cluster analysis) was performed on IPAH patients in the COMPERA registry, linking different phenotypes with survival [46]. It remains to be seen whether such phenotype classifications will affect therapeutic strategies for PAH patients in the future, as has been proposed for other disease entities, such as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [47]. In the recently published COMPERA cluster analysis [46] of 846 IPAH patients, 38% and 63% of “typical” patients (median age of 45 years old, without so-called “risk factors for left heart disease”) were treated with combined targeted PAH therapy within the first three months and after one year during follow-up, respectively. The other patients were predominantly treated with monotherapy at baseline and during follow-up.

It remains an important goal to treat PAH patients according to the current guidelines and reduce the gap between patients who do and do not receive aggressive combination therapy, when appropriate [48, 49]. Accordingly, recent data indicate that the use of combination therapy in patients with PAH increased continuously from 27% in 2010 to 42% in 2015 [50]. Nevertheless, targeted PAH drugs are prescribed less aggressively in patients over 65 years of age, which may impair survival, even after adjusting for age, when compared with younger PAH patients [51]. Our study (including a large spectrum of PAH patients) indicates a late initiation of combination therapy in patients over 65 years of age. This is comparable to recently published data from the COMPERA registry [46], in which the proportion of older patients receiving combination PAH therapy also increased over time. In our study, “typical” PAH patients received early combination therapy, as suggested by the guidelines, while older patients with more risk factors and comorbidities received this form of therapy later.

Despite these differences, the outcome of patients remaining on monotherapy during the entire observation period was not different from that of patients receiving dual or triple therapy. This was true for “atypical” as well as for “typical” PAH patients, although the number of patients was too small for a reliable survival analysis within each of these groups.

Conclusion

Considering these results, upfront combination therapy for “atypical” PAH patients may not be needed when PAH is complicated by advanced age and multiple comorbidities, since the outcome of monotherapy in these patients appears to be comparable to that of dual or triple therapy in “typical” PAH patients.

Availability of data and materials

To obtain access to the raw data please contact our statistician Dr. Anne Obst, E-Mail: anne.obst@uni-greifswald.de.

Abbreviations

- PAH:

-

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- IPAH:

-

idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PH:

-

pulmonary hypertension

- CTEPH:

-

chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- FC:

-

functional class

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

References

Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Noordegraaf AV, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Sanchez MAG, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M. ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) (vol 46, pg 903, 2015). Eur Respir J. 2015;46:1855–6.

Hoeper MM, Apitz C, Grunig E, Halank M, Ewert R, Kaemmerer H, Kabitz HJ, Kahler C, Klose H, Leuchte H, Ulrich S, Olsson KM, Distler O, Rosenkranz S. Ghofrani HA [targeted therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension: recommendations of the cologne consensus conference 2016]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2016;141:S33–41.

Galie N, Channick RN, Frantz RP, Grunig E, Jing ZC, Moiseeva O, Preston IR, Pulido T, Safdar Z, Tamura Y, McLaughlin VV. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. European Respiratory Journal 2019; 53.

Galie N, Palazzini M, Manes A. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: from the kingdom of the near-dead to multiple clinical trial meta-analyses. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2080–6.

Galie N, Manes A, Negro L, Palazzini M, Bacchi-Reggiani ML, Branzi A. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:394–403.

Ryerson CJ, Nayar S, Swiston JR, Sin DD. Pharmacotherapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2010;11:12.

He B, Zhang F, Li X, Tang C, Lin G, Du J, Jin H. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ J. 2010;74:1458–64.

Lajoie AC, Lauziere G, Lega JC, Lacasse Y, Martin S, Simard S, Bonnet S, Provencher S. Combination therapy versus monotherapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: a meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:291–305.

Opitz CF, Hoeper MM, Gibbs JS, Kaemmerer H, Pepke-Zaba J, Coghlan JG, Scelsi L, D’Alto M, Olsson KM, Ulrich S, Scholtz W, Schulz U, Grunig E, Vizza CD, Staehler G, Bruch L, Huscher D, Pittrow D, Rosenkranz S. Pre-capillary, combined, and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension: a pathophysiological continuum. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:368–78.

McLaughlin VV, Vachiery JL, Oudiz RJ, Rosenkranz S, Galie N, Barbera JA, Frost AE, Ghofrani HA, Peacock AJ, Simonneau G, Rubin LJ, Blair C, Langley J, Hoeper MM, Group AS. Patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension with and without cardiovascular risk factors: results from the AMBITION trial. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2019;38:1286–95.

Hoeper MM, Apitz C, Grunig E, Halank M, Ewert R, Kaemmerer H, Kabitz HJ, Kahler C, Klose H, Leuchte H, Ulrich S, Olsson KM, Distler O, Rosenkranz S, Ghofrani HA. Targeted therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension: updated recommendations from the cologne consensus conference 2018. Int J Cardiol. 2018;272S:37–45.

Boucly A, Weatherald J, Savale L, Jais X, Cottin V, Prevot G, Picard F, de Groote P, Jevnikar M, Bergot E, Chaouat A, Chabanne C, Bourdin A, Parent F, Montani D, Simonneau G, Humbert M, Sitbon O. Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2017; 50.

Hjalmarsson C, Radegran G, Kylhammar D, Rundqvist B, Multing J, Nisell MD, Kjellstrom B, SveFph, Spahr. Impact of age and comorbidity on risk stratification in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2018; 51.

Hoeper MM, Kramer T, Pan Z, Eichstaedt CA, Spiesshoefer J, Benjamin N, Olsson KM, Meyer K, Vizza CD, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Distler O, Opitz C, Gibbs JSR, Delcroix M, Ghofrani HA, Huscher D, Pittrow D, Rosenkranz S, Grunig E, Mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension: prediction by the, . European pulmonary hypertension guidelines risk stratification model. Eur Respir J. 2015;2017:50.

Bourge RC, Waxman AB, Gomberg-Maitland M, Shapiro SM, Tarver JH 3rd, Zwicke DL, Feldman JP, Chakinala MM, Frantz RP, Torres F, Cerkvenik J, Morris M, Thalin M, Peterson L, Rubin LJ. Treprostinil administered to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension using a fully implantable programmable intravascular delivery system: results of the delivery for PAH trial. Chest. 2016;150:27–34.

Olsson KM, Richter MJ, Kamp JC, Gall H, Heine A, Ghofrani HA, Fuge J, Ewert R, Hoeper MM. Intravenous treprostinil as an add-on therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2019;38:748–56.

Badagliacca R, Papa S, Poscia R, Valli G, Pezzuto B, Manzi G, Torre R, Gianfrilli D, Sciomer S, Palange P, Naeije R, Fedele F, Vizza CD. The added value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the follow-up of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2019;38:306–14.

Bartolome SD, Sood N, Shah TG, Styrvoky K, Torres F, Chin KM. Mortality in Patients With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Treated With Continuous Prostanoids. Chest. 2018;154:532–40.

Galie N, Barbera JA, Frost AE, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, McLaughlin VV, Peacock AJ, Simonneau G, Vachiery JL, Grunig E, Oudiz RJ, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, White RJ, Blair C, Gillies H, Miller KL, Harris JH, Langley J, Rubin LJ, Investigators A. Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:834–44.

Pulido T, Adzerikho I, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Galie N, Ghofrani HA, Jansa P, Jing ZC, Le Brun FO, Mehta S, Mittelholzer CM, Perchenet L, Sastry BK, Sitbon O, Souza R, Torbicki A, Zeng X, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G, Investigators S. Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:809–18.

Sitbon O, Channick R, Chin KM, Frey A, Gaine S, Galie N, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, Lang IM, Preiss R, Rubin LJ, Di Scala L, Tapson V, Adzerikho I, Liu J, Moiseeva O, Zeng X, Simonneau G, McLaughlin VV, Investigators G. Selexipag for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2522–33.

Hoeper MM, Huscher D, Pittrow D. Incidence and prevalence of pulmonary arterial hypertension in Germany. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:612–3.

Badesch DB, Raskob GE, Elliott CG, Krichman AM, Farber HW, Frost AE, Barst RJ, Benza RL, Liou TG, Turner M, Giles S, Feldkircher K, Miller DP, McGoon MD. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: baseline characteristics from the REVEAL registry. Chest. 2010;137:376–87.

Rich S, Dantzker DR, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, Fishman AP, Goldring RM, Groves BM, Koerner SK, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension. A national prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:216–23.

Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V, Yaici A, Weitzenblum E, Cordier JF, Chabot F, Dromer C, Pison C, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Haloun A, Laurent M, Hachulla E, Simonneau G. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: results from a national registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1023–30.

Escribano-Subias P, Blanco I, Lopez-Meseguer M, Lopez-Guarch CJ, Roman A, Morales P, Castillo-Palma MJ, Segovia J, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Barbera JA, Investigators R. Survival in pulmonary hypertension in Spain: insights from the Spanish registry. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:596–603.

Hurdman J, Condliffe R, Elliot CA, Davies C, Hill C, Wild JM, Capener D, Sephton P, Hamilton N, Armstrong IJ, Billings C, Lawrie A, Sabroe I, Akil M, O’Toole L, Kiely DG. ASPIRE registry: assessing the Spectrum of Pulmonary hypertension Identified at a REferral centre. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:945–55.

Hoeper MM, Huscher D, Ghofrani HA, Delcroix M, Distler O, Schweiger C, Grunig E, Staehler G, Rosenkranz S, Halank M, Held M, Grohe C, Lange TJ, Behr J, Klose H, Wilkens H, Filusch A, Germann M, Ewert R, Seyfarth HJ, Olsson KM, Opitz CF, Gaine SP, Vizza CD, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Kaemmerer H, Gibbs JS, Pittrow D. Elderly patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the COMPERA registry. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:871–80.

Heresi GA, Love TE, Tonelli AR, Highland KB, Dweik RA. Choice of initial oral therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: age and long-term survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1090–3.

Kylhammar D, Kjellstrom B, Hjalmarsson C, Jansson K, Nisell M, Soderberg S, Wikstrom G, Radegran G. A comprehensive risk stratification at early follow-up determines prognosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:4175–81.

Mclaughlin VGN, Barbera JA, Frost A, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper M, Peacock AJ, Simmoneau G, Vachiery J-L, Blair C, Gillies HC, Harris J, Langley J, Rubin LJ. A comparison of characteristics and outcomes of patients with atypical and classical pulmonary arterial hypertension from the AMBITION trial [abstract]. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2015;191(Astr Suppl):2196.

Swinnen K, Quarck R, Godinas L, Belge C, Delcroix M. Learning from registries in pulmonary arterial hypertension: pitfalls and recommendations. Eur Respir Rev 2019; 28.

Pieske B, Tschope C, de Boer RA, Fraser AG, Anker SD, Donal E, Edelmann F, Fu M, Guazzi M, Lam CSP, Lancellotti P, Melenovsky V, Morris DA, Nagel E, Pieske-Kraigher E, Ponikowski P, Solomon SD, Vasan RS, Rutten FH, Voors AA, Ruschitzka F, Paulus WJ, Seferovic P, Filippatos G. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3297–317.

Tonelli AR, Plana JC, Heresi GA, Dweik RA. Prevalence and prognostic value of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in idiopathic and heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2012;141:1457–65.

Benza RL, Miller DP, Foreman AJ, Frost AE, Badesch DB, Benton WW, McGoon MD. Prognostic implications of serial risk score assessments in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL) analysis. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2015;34:356–61.

Weatherald J, Boucly A, Sitbon O. Risk stratification in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24:407–15.

Pabst S, Hammerstingl C, Hundt F, Gerhardt T, Grohe C, Nickenig G, Woitas R, Skowasch D. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with chronic kidney disease on dialysis and without dialysis: results of the PEPPER-study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35310.

Ortwein J, Feustel A, Reichenberger F. Prevalence of pulmonary hypertension in dialysis patients with end-stage renal disease. Pneumologie. 2020;74:210–6.

Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, Williams PG, Souza R. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019; 53.

Regan JA, Kitzman DW, Leifer ES, Kraus WE, Fleg JL, Forman DE, Whellan DJ, Wojdyla D, Parikh K, O’Connor CM, Mentz RJ. Impact of age on comorbidities and outcomes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:1056–65.

Vanfleteren LE, Spruit MA, Groenen M, Gaffron S, van Empel VP, Bruijnzeel PL, Rutten EP, Op’t Roodt J, Wouters EF, Franssen FM. Clusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:728–35.

Lang IM, Palazzini M. The burden of comorbidities in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019;21:K21–8.

Rosenkranz SCR, Chin K, Jenner B, Gaine S, Galie N, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, Mclaughlin VV, Preiss R, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, Tapson V, Lang IM. Efficacy and safety of selexipag in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients with and without significant cardiovascular (CV) comorbidities. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:4973.

Badagliacca R, Rischard F, Papa S, Kubba S, Vanderpool R, Yuan JX, Garcia JGN, Airhart S, Poscia R, Pezzuto B, Manzi G, Miotti C, Luongo F, Scoccia G, Sciomer S, Torre R, Fedele F, Vizza CD. Clinical implications of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension phenotypes defined by cluster analysis. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2020;39:310–20.

Forfia PR, Vaidya A, Wiegers SE. Pulmonary heart disease: The heart-lung interaction and its impact on patient phenotypes. Pulm Circ. 2013;3:5–19.

Hoeper MM, Pausch C, Grunig E, Klose H, Staehler G, Huscher D, Pittrow D, Olsson KM, Vizza CD, Gall H, Benjamin N, Distler O, Opitz C, Gibbs JSR, Delcroix M, Ghofrani HA, Rosenkranz S, Ewert R, Kaemmerer H, Lange TJ, Kabitz HJ, Skowasch D, Skride A, Jureviciene E, Paleviciute E, Miliauskas S, Claussen M, Behr J, Milger K, Halank M, Wilkens H, Wirtz H, Pfeuffer-Jovic E, Harbaum L, Scholtz W, Dumitrescu D, Bruch L, Coghlan G, Neurohr C, Tsangaris I, Gorenflo M, Scelsi L, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Ulrich S, Held M. Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension phenotypes determined by cluster analysis from the COMPERA registry. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2020;39:1435–44.

Samson R, Jaiswal A, Ennezat PV, Cassidy M, Le Jemtel TH. Clinical phenotypes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5.

Small M, Piercy J, Pike J, Cerulli A. Incremental burden of disease in patients diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension receiving monotherapy and combination vasodilator therapy. Adv Ther. 2014;31:168–79.

Farber HW, Miller DP, Meltzer LA, McGoon MD. Treatment of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension at the time of death or deterioration to functional class IV: insights from the REVEAL Registry. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2013;32:1114–22.

Burger CD, Pruett JA, Lickert CA, Berger A, Murphy B, Drake W 3rd. Prostacyclin use among patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension in the united states: a retrospective analysis of a large health care claims database. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:291–302.

Sitbon O, Howard L. Management of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients aged over 65 years. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019;21:K29–36.

Acknowledgements

We explicitly thank Mrs. Dagmar Fimmel, Mrs. Kathrin Gutsche, and the documentarian Mrs. Irena Mennel. All authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Grant from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BS, RE, CFO, HJS, JK, MH, HG, SD made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. AO, BS, RE and CFO were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors were involved in drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and have provided final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent was waived by an Institutional Review Board (IRB). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Greifswald (Reg. No. BB 167/18, with an amendment to extend the observation period). No administrative permissions and/or licenses were acquired by our team to access the clinical/personal patient data used in our research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Stubbe, B., Seyfarth, HJ., Kleymann, J. et al. Monotherapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension at four German PH centres. BMC Pulm Med 21, 130 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01499-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01499-2