Abstract

Introduction

Childhood undernutrition has been investigated extensively in previous literature but gender inequality detailing the burden of undernutrition has not been adequately addressed in scientific papers, especially in Ethiopia, where undernutrition is known to be a public health problem of high significance, necessitating increased efforts to address it and reduce this inequality. This study was carried out to: (1) explore gender differences in the prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight, and (2) compare the factors associated with childhood undernutrition between boys and girls in Ethiopia.

Methods

The study used a dataset of more than 33,564 children aged under 5 years (boys: 17,078 and girls: 16,486) who were included in the nationally representative Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) from 2000 to 2016. The outcome variables were anthropometric indices: stunting (height-for-age < -2 standard deviations), wasting (weight-for-height < -2 standard deviations), and underweight (weight-for-age < -2 standard deviations). Gender-specific multilevel analyses were used to examine and compare the factors associated with child undernutrition.

Results

The overall prevalence of stunting (49.1% for boys vs 45.3% for girls, p < 0.001), wasting (11.9% for boys vs 9.9% for girls, p < 0.001), and underweight (33.1% for boys vs 29.8% for girls, p < 0.001) higher among boys compared to girls. Boys significantly had higher odds of stunting (aOR: 1.31, 95%CI: 1.21–1.42), wasting (aOR: 1.35, 1.23–1.48), and underweight (aOR: 1.38, 95%CI: 1.26–1.50) than girls. The common factors associated with childhood undernutrition for male and female children were the child's age, perceived size of the child at birth, breastfeeding status, maternal stature, maternal education, toilet facility, wealth index, and place of residence. Boys who were perceived by their mothers to be average sized at birth and were born to uneducated mothers had a higher likelihood of experiencing wasting, in contrast to girls. Among boys, birth order (firstborn), household size (1–4), and place of residence (urban) were associated with lower odds of being underweight. Boys living in cities had lower odds of being stunted. While girls born to mothers with no education and worked in agriculture were at a higher odd of being stunted.

Conclusion

Our study revealed that boys were more likely to be malnourished than girls, regardless of their age category, and there were variations in the factors determining undernutrition among boys and girls. The differences in the burden of undernutrition were significant and alarming, positioning Ethiopia to be questioned whether it will meet the set Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 2 of zero hunger by 2030. These findings call for more effort to address malnutrition as a significant public health issue in Ethiopia, and to urgently recognise the need for enhanced interventions that address the gender gap in childhood undernutrition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Undernutrition is associated with about 45% of all childhood deaths and continues to be of one of the greatest public health concerns in many low-middle-income (LMIC) countries [1]. Childhood undernutrition is known to be a cause of severe morbid and significant mortality rates in children and manifests in three broad forms including: wasting, stunting, and underweight. Stunting, which is the condition of being too short for a child’s age, undermines physical and cognitive development, increasing the risk of dying from common infections and predisposing them to non-communicable diseases later in life [2,3,4,5]. Wasting, which is defined as too low weight than expected for the child’s height, is an acute condition that can change frequently and rapidly over a calendar year [5]. Underweight is a composite index that accounts for both acute and chronic undernutrition [1, 2].

Globally in 2020, an estimated 149 million (22%) children under-five years of age were stunted, and 45 million (7%) were wasted [5]. The numbers show persistent regional disparities, with Africa bearing the heaviest burden of all forms of undernutrition. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), two out of five stunted children worldwide and over one-quarter of all wasted children under-five live in Africa [2]. Despite agreeing to work towards reversing all forms of malnutrition by 2030, the pace of necessary actions in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, including Ethiopia, is still lower than acceptable [6, 7].

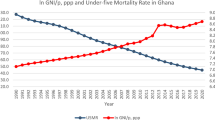

Ethiopia, a country long known for its significant burden of undernutrition, has been implementing a number of nutrition programs to combat undernutrition [7, 8], including the recent “Seqota Declaration” which aimed to end stunting in children under two years by 2030 [9]. Whilst impressive progress has been made in overall undernutrition in Ethiopia, with a decline in the prevalence of stunting from 51 to 37%, wasting from 12 to 7%, and underweight from 33 to 21% between 2005 and 2019 [10, 11], the reduction is not sufficient to meet the 2030 target. Additionally, studies have revealed the existence of gender disparities in undernutrition in Ethiopia and SSA countries, inequitably thwarting the expected progress [12,13,14,15,16].

A wide range of childhood undernutrition risk factors including maternal nutritional status and sociodemographic characteristics [17,18,19,20,21], environmental factors [19, 22, 23], and child related factors-such as the age of the child [17, 24, 25], size at birth [20, 21], complementary food starting before 6 months [26], lack of exclusive breastfeeding [18], and diarrhea [12, 18, 26,27,28] have been stated to be determinants of undernutrition. One of the children's risk factor is its sex [12, 25, 27, 29]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of sex differences in undernutrition that included 74 studies identified that boys had higher odds of being stunted, wasted, and underweight than girls [30]. Likewise, further analysis of the 2019 Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey (EMDHS) revealed significant gender disparities in the burden of childhood undernutrition in Ethiopia [31]. These findings, although focused on a limited set of indicators, showed that understanding the determinants of undernutrition in boys and girls is paramount.

There have been a number of studies on childhood undernutrition among Ethiopian children [32,33,34,35]. However, as far as is known, there is a scarcity of the evidence that identified the different risk factors of undernutrition comparing boys and girls in Ethiopia. The only study that could be found was the one by Samuel and colleagues who focused on gender differences in nutritional status [36], and which was also limited to infants aged between 6 and 11 months. This study also investigated stunting and wasting, and was localized in two regions, hence limiting its generalisability at the national level [36]. Another study by Wang et al. [37] used a decomposition technique to evaluate the differences in nutritional outcomes by observable factors and socio-economic characteristics using the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) 2011. Apart from these two studies, past studies in Ethiopia have mainly focused on urban–rural inequalities [31], socioeconomic inequality [32,33,34, 37], and many concentrated on the spatial analysis of one or more forms of undernutrition [19, 23, 38,39,40, 40, 41]. For example, although Negasi (2021) used the Ethiopia Socioeconomic Survey (ESS) to investigate inequalities in childhood undernutrition, their focus was on socioeconomic status [33], Jember et al. (2021) [42], and Tesema et al. [38] focused on geospatial inequality of anaemia among children. These studies provided insight about forms of inequality, however, non- as focused on gender inequalities. Thus, it is important to gain an understanding of the undernutrition inequalities that exist between boys and girls, as well as to identify potential risk factors that lead to such differences during their first five years of life.

To fill this gap of the literature, our aim was twofold as follows, to: (i) describe the prevalence of childhood undernutrition, specifically targeting it common but important forms, i.e., stunting, wasting and underweight among boys and girls, and (ii) identify their risk factors according to the gender of the child. This study will contribute and improve the dearth of information and existing data gaps in gender inequality in undernutrition in Ethiopia. Additionally, the study also will contribute evidence that will enhance information towards the global commitment of "Leaving no one behind" from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda Goal 2 target 2.2.

Methods

Data sources and sampling design

This analysis used data from four rounds of the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) conducted in 2000, 2005, 2011, and 2016 [10, 43,44,45]. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey is a nationally representative cross-sectional household survey, being also representative at regional and area of residence (urban/rural) levels. The EDHS sampling and household listing methods are described elsewhere [45]. We included children aged 0–59 months born to mothers aged 15–49 years. Children's height and weight measurements were obtained, and anthropometric indices (height-for-age, weight-for-height, and weight-for-age) were calculated. Children were excluded if they lacked anthropometric measures or had implausible values (values < -6 SDs and > + 6 SDs). We used information from 33,564, 33,583, and 33,729 children (weighted sample) who were born 5 years before the surveys were included to analyze stunting, wasting, and underweight, respectively.

Outcome variables

The outcome variables of the study were stunting, wasting, and being underweight. Height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-height (WHZ), and weight-for-age (WAZ) z-scores below − 2 SDs of the WHO Child Growth Standard were used to define stunting, wasting, and underweight, respectively [46].

Independent variables

The independent variables were selected based on previous literature [47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. The selected variables were classified into three categories according to the UNICEF’s conceptual framework of malnutrition: immediate (individual-level factors), underlying (household-level factors), and basic (community-level factors) determinants [54]. The individual-level determinants consisted of child characteristics (age in months, birth order, birth interval, size at birth, breastfeeding status, diarrhea and fever in the past 2 weeks) and maternal characteristics (age, education, occupation, stature, listening to the radio, and watching television). The household-level covariates included wealth index, household number of residents, type of toilet facility, source of drinking water, and time to get to a water source. The community-level factors include the place of residence (urban or rural), contextual region of residence (agrarian, pastoralist, and city administration), and survey year. Variable descriptions for various independent variables are described in Supplementary File 1.

The household wealth index was calculated using the principal components analysis method. Households are given scores based on the number and kinds of consumer goods they own, ranging from a television to a bicycle or car, in addition to housing characteristics such as source of drinking water, toilet facilities, and flooring materials. The wealth index was categorized into wealth quintiles: 'very poor', 'poor', 'middle', 'rich' and 'very rich [45]. For this analysis, we re-coded the wealth index into three categories for adequate sampling in each category: 'poor' (poor and very poor), 'middle' and 'rich' (rich and very rich) [22].

Data analysis

All analyses were carried out using STATA/MP version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The survey command (svy) was used to take into account the sampling design of the survey. Descriptive statistics such as absolute and relative frequencies were used to present the distribution of all variables and stratified by sex (male or female). A comparison between undernutrition indicators according to child’s sex was carried out. The Chi-squared test and a 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to compare the prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight by sex. Then, differences in the prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight by gender were presented using equiplot graphs, which visually represent absolute inequalities. These graphs make it easy for non-specialists to grasp the idea of gender inequalities (https://equidade.org/equiplot).

Gender-specific disaggregated analyses were conducted to identify factors associated with outcome variables. Given the hierarchical nature of the EDHS data, a two-level multilevel binary logistic regression model was built with individuals (level 1) nested within communities (level 2). Accordingly, four models were constructed in this analysis. The empty model (Model I) was fitted without explanatory variables to estimate random variation in the intercept. Model II was constructed to examine the effects of individual-level characteristics, Model III was fitted to assess the effects of community-level characteristics, and Model IV adjusted for the individual- and community-level variables simultaneously. Separate models were run for boys and girls for stunting, wasting, and underweight to explore the individual and community-level factors associated with child undernutrition according to sex. We present the disaggregated analysis results for girls and boys in a condensed table. In the model-building process, we first performed unadjusted bivariate multilevel models disaggregated by the sex for each pair of outcome and covariate. Variables in bivariable analysis with a p-value < 0.2 and known confounder variables were entered into the multilevel multivariate logistic regression model. A multicollinearity test was performed among independent variables, and no evidence of multicollinearity was found. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was computed for each model to evaluate whether the variation in outcome variable is primarily within or between communities. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) was estimated. A significance level of 5% was considered in all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Table 1 presents the weighted proportion of demographic characteristics of the study sample. In all datasets, almost 49.0% of under-five children were girls. Most of the children were born to mothers with no schooling (72.8%), rural residents (89.3%), and poor households (45.4%). Occurrence of diarrhea was slightly higher among boys (17.4% vs. 16.3%, p = 0.002), and more girls were small at birth (34.1% vs. 25.3%, p < 0.001). Breastfeeding initiation within one hour of post-partum was similar between boys and girls (53.7% vs. 54.8%, p = 0.108).

Prevalence of stunting

Table 1 also shows the weighted prevalence of child undernutrition and gender-based inequalities. The overall prevalence of stunting among children under the age of five years was 47.3% (95%CI: 46.8–47.8). The overall prevalence of stunting was higher among male than female children (49.2% vs. 45.4%, p < 0.001).

Prevalence of wasting

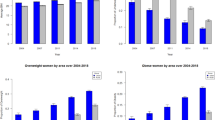

The overall prevalence of wasting among children under the age of five years was 10.9% (95%CI: 10.6–11.3). The prevalence of wasting was also higher among boys than girls (11.95% vs. 9.92%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Prevalence of underweight

The overall prevalence of underweight among children under the age of five years was 31.5% (31.0–32.0). The prevalence of underweight was also higher among boys than girls (33.13% vs. 29.83%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Prevalence of stunting, wasting and underweight by gender

Figures 2, 3 and 4 reported 16 years prevalence of stunting, wasting and underweight and their 95% CIs by gender. Overall, the prevalence stunting, wasting and underweight seem to has been reduced in the past 16 years with girls reporting lower prevalence than boys (Fig. 5). Compared to EDHS-2000, the prevalence of stunting and underweight has also been reduced significantly, this was not the same for the prevalence of wasting which appeared to have been reduced but did not differ statistically to that of EDHS-2016 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary File 2).

The differences in the prevalence of undernutrition between boys and girls stratified by EDHS survey year and age are presented in Fig. 6. Across all age groups (i.e., < 6 months, 6–11, 12–23, 24–35, and 36–59 months) male children had a higher prevalence of stunting, wasting and underweight compared to girls (Supplementary Files 3, 4 and 5).

Factors associated with stunting, wasting and underweight in male and female children

The results of the multilevel bivariable logistic regression analysis for stunting, wasting, and underweight for boys and girls are shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Table 5 and Supplementary File 6 present the condensed tables for multilevel multivariable analysis results. Overall, boys significantly had higher odds of stunting (AOR: 1.31, 95%CI: 1.21–1.42), wasting (AOR: 1.35, 1.23–1.48), and underweight (AOR: 1.38, 95%CI: 1.26–1.50) than girls.

Factors associated with stunting in male and female children

Table 5 presents a multilevel gender-specific disaggregated analysis for all outcome variables. Several factors were associated with childhood stunting in male and female children. At the individual level, the age of the child, perceived size of the child at birth, breastfeeding status, maternal stature, and type of the toilet facility at home were associated with stunting in both male and female children. At the community level, the place of residence (urban) showed a significant association with childhood stunting in both male and female children.

However, there are variations in the factor identified with childhood stunting among boys and girls. Unlike male children, for female children, mother's age, education level of the mother, mother's occupation and household wealth index, were determinants of childhood stunting. Female children born of mothers with no education (AOR: 1.30, 95%CI: 1.12–1.50) and working in agriculture (AOR: 1.33, 95%CI: 1.14–1.55) had higher odds of stunting. Among female children, the odds of stunting were lower among children from a household with a middle (AOR: 0.73, 95%CI: 0.62–0.87) and rich wealth index (AOR: 0.76, 95%CI: 0.64–0.90). On the other hand, unlike girls, boys living in cities had lower odds of being stunted (AOR: 0.70, 95%CI: 0.57–0.86) (Table 5).

Factors associated with wasting in male and female children

Both individual and community-level factors were associated with wasting in both male and female children. The child's age (except those in the age category of 24–35 months), the perceived size of the child at birth (small birth size), the presence of diarrhea and fever, the mother's education, maternal stature, wealth index (rich households), and place of residence were identified factors associated with wasting in boys and girls (Table 5).

Unlike the girls, the odds of wasting were higher (AOR: 1.29, 95%CI: 1.06–1.58), for male children aged 24–35 months compared to children aged 36–59 months. There were higher odds of wasting among male children who were perceived by their mothers to be average sized at birth (AOR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.09–1.49). Male children born to mothers with no education (AOR: 1.32, 95%CI: 1.12–1.55) were associated with higher odds of wasting. Children from a household with a middle wealth status (AOR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.61–0.88) were associated with reduced odds of wasting (Table 5).

In female children, the child's age, the perceived size of the child at birth, diarrhea, fever in the last two weeks prior to the survey, household wealth index, and residence were similar determinants of wasting to that of male children. However, unlike boys, the odds of wasting were significantly higher among female children not fully vaccinated (AOR: 1.24, 95%: 1.02–1.52). Female children in a household with an unimproved toilet facility (AOR: 1.33, 95%CI: 1.01–1.74) were associated with increased odds of wasting. However, we observed an inverse association between unimproved sources of drinking water and childhood wasting (AOR: 0.80, 95%CI: 0.67–0.95) (Table 5).

Factors associated with underweight in male and female children

The child's age, size of child at birth, diarrhea, and fever in the last two weeks, mother's education status, maternal stature, household wealth index, and toilet facility were factors associated with being underweight in both male and female children. Among male children, the odds of being underweight were lower among firstborn children (AOR: 0.77, 95%CI: 0.59–0.98), children living with 1–4 household size (AOR: 0.84, 95%CI: 0.72–0.98), and those from urban setting (AOR: 0.72, 95%CI: 0.56–0.93). On the other hand, among female children, the odds of being underweight were higher among children who were not fully vaccinated (AOR: 1.21, 95%CI: 1.03–1.41), had a fever in the last two weeks prior to the survey, and children born in households whose water source was away from the house for more than 60 min round trip (AOR: 1.45, 95%CI: 1.04–2.02) (Table 5).

Discussion

Despite the significant impact of childhood undernutrition on child survival and development in Ethiopia, few studies have focused on gender inequality and identification of associated risk factors. Although a limited number of studies have been conducted in Ethiopia on childhood stunting, wasting and underweight among Ethiopian children [19, 21, 23, 29, 55,56,57,58], investigation of the burden of undernutrition focusing on gender inequality has not been adequately addressed in scientific papers [37, 59, 60] and efforts to reduce this inequality are rarely seen. Moreover, inequality studies primary focus on socioeconomic inequality [32,33,34, 37]. To our knowledge, our study is the first of its kind to assess the prevalence and factors associated with childhood undernutrition between boys and girls, using a nationally representative sample of children aged between 0 and 59 months in Ethiopia. Our findings showed that in Ethiopian, there are gender differences in childhood undernutrition in under-five children, with boys being more likely than girls to be stunted, wasted, and underweight. The common significant factors for childhood stunting in male and female children were the child's age, the perceived size of the child at birth, breastfeeding status, maternal stature, type of toilet facility, and place of residence. However, when comparing boys and girls, there are differences in risk factors for stunting, wasting, and underweight. Among female children, the education level of the mother, the mother's occupation, and the household wealth index were further identified as factors associated with childhood stunting. Unlike girls, the odds of wasting was higher for male children who were perceived by their mothers to be average sized at birth and children born to mothers with no education. Additionally, among male children, the odds of being underweight were lower among firstborn children, children living in 1–4 household size, and those from urban setting.

In this study, through all age groups (i.e., < 6 months, 6–11, 12–23, 24–35, and 36–59 months) and across all survey years male children had a higher prevalence of stunting, wasting and underweight compared to girls. The present analysis provides the evidence that inform the role that gender plays in childhood undernutrition in Ethiopia, highlighting the necessity of sex-specific nutritional interventions for promoting optimal child growth and development in the country. The high prevalence of undernutrition among boys observed in the current analyses is consistent with previous findings from Ethiopia [12, 14, 61, 62]. This finding is also consistent with the most recent systematic review and meta-analysis, which found that boys had a higher risk of stunting, wasting, and being underweight than girls [30]. Additionally, pooled evidence of studies conducted from 2008 to 2020 from 35 sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries reported that being a male child was associated with higher odds of stunting [63]. The higher likelihood of male children being wasted in this study mirrors the previous findings in India and Ghana [64, 65]. Similarly, prior studies in Ethiopia [62], and different low-income settings such as Kenya [66], Rwanda [67], Senegal [68], Tanzania [69] and Indonesia [70] have reported that being underweight was the most common undernutrition problem among boys than girls. Our study extends the body of knowledge including informing the need to put significant emphasis of targeting a male child in addressing undernutrition, thus addressing gender inequality As well, given that the previous studies in Ethiopia have had one of the following limitations: either dated (e.g. survey specific and based on the 2011 EDHS [37]), consisted of a narrower age band, socioeconomic status or geographically specific [36], they limited their generalisability at the national level.

Studies investigating the role of gender on child development are still limited in Ethiopia. However, many questions remain unanswered, such as the causal direction of undernutrition and gender and the possible mechanism that explains this interaction in children aged under five years. Several possible explanations have been reported concerning gender differences in undernutrition status. According to Thompson (2021) [71], boys may be more vulnerable to illness and malnourishment due to sex differences in immune system development. Sex-based biological factors may also make boys more vulnerable to infection [30, 71]. There is also evidence that, men are more susceptible to infections than women [72,73,74], and that boys are more likely to be born preterm, increasing their risk for most adverse neonatal outcomes [75] and a higher risk of perinatal complications [76]. Furthermore, studies show that boys have a shorter median duration of predominant breastfeeding than girls [45], and there are differences in growth and immune function between these two genders [77]. The roles that boys and girls play in a community, as well as the values associated with them, may have an impact on their nutritional status [78]. Identifying the various causes, mechanisms, and effects of sex variations in undernutrition necessitates additional research to discover whether sex differences affect child growth, development and long-term morbidity and mortality rates.

A child's age is a common determinant of stunting for both boys and girls. The odds of stunting were lower among young children (i.e., aged 0–23 months) than those in the age category of 36–59 months in both sexes, consistent with several other related studies conducted elsewhere [56, 79,80,81,82,83]. The observed lower odds of stunting among children aged 0 to 23 months could be explained by the protective effect of breastfeeding, as most Ethiopian children are breastfed until the age of two years [84]. Additionally, in countries like Ethiopia where food security is still a serious issue, a lack of adequate and balanced food intake to meet the metabolic demand of older children leaves a child vulnerable to a high risk of stunting. Further studies could examine which age groups, genders, and why they do suffer from undernutrition.

Our study revealed that the likelihood of stunting was higher among children perceived by their mothers as smaller and average size than normal at birth among boys and girls. In agreement with the current study, previous studies in India, Bangladesh, and Nepal have also stated that children born with smaller than average size were more prone to stunting [85,86,87]. We speculate that the observed results may be due to children's low birth weight, which may have an effect on child liner growth. In our study, having a very short and short mother was associated with increased odds of stunting among children of both sexes. Stunting is related to maternal stature [88,89,90]. This finding evidenced that stunting is passed from one generation to the next in an intergenerational cycle, indicating that children born to stunted mothers are more likely to be stunted themselves [4, 91].

The relationship between unimproved water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and child undernutrition has been widely acknowledged by previous literature [22, 92,93,94]. Not surprisingly, in the current study, children in households with inadequate toilet facilities were at a higher risk of stunting. The findings suggest that children living in households with poor toilet facilities or in areas where open defecation was widespread were more vulnerable to stunting, which could be attributed to frequent episodes of diarrheal disease. Diarrhea contributes to nutritional deficiencies by reducing food intake, decreasing nutrient absorption, and promoting nutrient catabolism. There is a clear biological mechanism and plausibility for the impact of WASH access on nutritional status. WASH is dependent not just on the availability of factors including water and sanitation facilities, but also on proper health behaviors (e.g., hand washing at crucial times) by all or key members of the family (e.g., caregiver cleaning a child's hands). Hence, attention to this issue is of particular importance, as large interventional studies, such as the WASH-Benefits Bangladesh [95], the WASH-Benefits Kenya [96] and the Sanitation Hygiene Infant Nutrition Efficacy (SHINE) trials in Zimbabwe [97] have found no effects of any WASH intervention on child linear growth. These findings suggest that poor WASH affects children’s developmental processes in complex ways, spanning multiple routes.

Among the girl children, our study indicates that children born to mothers with no education and working in agriculture were more likely to be stunted. The growing body of evidence connects maternal employment to children's nutritional status. For example, one study from the nine Demographic and Health Surveys conducted in various countries (Benin, Burundi, Cambodia, Congo, Haiti, Rwanda, Senegal, Togo, and Uganda) found that parental agricultural employment, relative to non-agricultural employment, was associated with poorer child development [98]. Further studies could further explore why certain maternal employment influenced children's nutritional status in different sexes.

Similar to previous studies [99, 100], a significant association between mothers' education and stunting was found. This result is more predictable because education gives mothers the information necessary to be knowledgeable about child nutrition, hygiene, and health. That is, a mother with a higher level of education is associated with better childcare practices. Studies have also found that knowledge of these things strongly predicts stunting in children under five years [101].

This finding reaffirms that children from relatively wealthiest households and living in an urban setting were less likely to be stunted compared to their counterparts. This association may reflect that greater wealth ensures a sufficient nutritionally balanced household food supply and a better living environment, and a variety of other essential characteristics for effective child growth and development. Additionally, previous studies in Ethiopia [14, 15], Rwanda [102], Ghana [103], and Tanzania [104] found a link between higher wealth status and a lower risk of undernutrition.

In our analyses, for both boys and girls of younger age, children who were perceived by their mothers to be smaller than normal at birth, children who had diarrhea and fever in the last two weeks prior to the survey and living in urban residences were significant independent risk factors of childhood wasting. Our findings also indicate that children from relatively wealthiest households had lower odds of wasting than children from poor households for both sexes. We hypothesize that children from richer households afford foods high in nutritional value, have lower intestinal infections and live in food secure households. Corresponding with our findings, the World Health Organizations Framework for Social Determinants of Health (SDH) acknowledged that poverty, low level of education, the environment where people live and work, determine population health outcomes [105].

Unlike girls, boys born to mothers with no education had higher odds of being wasted. On the other hand, those living in households with unimproved toilet facilities was one of the factors associated with wasting among girls. These results corroborate other studies, where children who had diarrhea [28], reported to have been born with low birth size [106,107,108], living in urban areas [27], and had poor socioeconomic status [28, 109] were more likely to be wasted.

Several factors were associated with child underweight in both boys and girls. The most consistent factors identified were younger child age, the perceived size of the child at birth, diarrhea, maternal education, maternal stature, watching television, wealth index, and household sanitation facility. However, among boys, birth order, household size, and place of residence were important factors significantly associated with being underweight. On the other hand, vaccination status, having fever, and time taken for a round trip to water sources were the identified factors associated with being underweight for girls.

The odds of being underweight were higher among children perceived as small size at birth. This is similar to various reports in Ethiopia and elsewhere [29, 64, 69, 110], confirming that birth size was an important determinant factor that significantly affected the nutritional status. The lower odds ratios of underweight for children in age groups (< 6 months and 6 to 11 months) observed among boys and girls also supports other studies from Bangladesh [111]. Our findings are consistent with other research showing strong positive associations between underweight and diarrhea in the last two weeks [29, 112, 113], short-statured mothers [114, 115], mothers with no education [29, 69, 112], and children from households that used unimproved toilets [69, 116, 117]. Our study also emphasized that children under five years from relatively wealthiest households are at a lower risk of being underweight than children from poor households [29, 111]. Wealth status serves as a substitute for higher socioeconomic status that improves the ability of mothers to afford the cost of nutritious food and ensured household food security. Children’s from relatively wealthiest households were found at lower risk of being underweight. The other finding of this study is birth order and place of residence, which had a strong positive association with being underweight. In agreement with related studies, boys' probability of being underweight for a firstborn child [29] and those residing in an urban setting [118] was lower.

Limitations

The study has certain limitations. First, since this study was based on cross-sectional data, it could not provide evidence of a causal relationship between outcome and independent variables. Second, due to the unavailability of data on potential confounders, including household food security, the behavior of the parents, and underlying disease conditions, these were not included in the analysis. Third, some data on personal and household practices were based on the mothers’ recall, which might have been subjected to recall bias. Fourth, the pooling of the data may be affected by heterogeneity across survey years. Despite these limitations, the data were collected from across the country, making it a nationally representative study. In addition, using a nationwide population-based dataset provides a large sample size and statistical power to study identify factors for childhood stunting, wasting and underweight among under-five boys and girls in Ethiopia. Additionally, having used the national survey dataset from across multiple years when the four consecutive Ethiopia Demographic and Health Surveys were conducted (2000 to 2016), our findings provide a nationwide assessment of gender differentials in childhood undernutrition, and compares the prevalence of different forms of this significant health problem across the years, contributing evidence from the context of the whole of Ethiopia and over time. Further investigation is needed to understand how gender-sensitive interventions targeting child growth are successful and economically feasible, and we are aware that such studies are scarce in low-income countries such as Ethiopia.

Conclusions

Our analyses show that childhood stunting, wasting, and being underweight were higher among boys than girls. The most consistent factors for childhood undernutrition for male and female children were the child's age, the perceived size of the child at birth, breastfeeding status, maternal stature, maternal education, toilet facility, wealth index, and place of residence. However, among female children, education level, the mother's occupation, and the household wealth index were factors identified to be associated with childhood stunting. Unlike girls, boys born to mothers with no education had higher odds of being wasted. On the other hand, those living in households with unimproved toilet facilities were more likely to have wasting among girls. Among boys, birth order and place of residence were important factors, significantly associated with being underweight. Moreover, vaccination status, fever, and time taken to get to and from the water sources were the factors identified to be associated with being underweight for girls. Overall, child sex has been identified as an important risk factor for childhood undernutrition in Ethiopia. Recently the government of Ethiopia endorsed 2019 Food and Nutrition Policy which aims to achieve optimal nutritional status throughout the life cycle via implementation of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions. The current finding will benefit and inform this policy as it informs the need to emphasize on gender-sensitive interventions to optimize infant and young child nutritional status. Furthermore, the Seqota Declaration, in which Ethiopia has made commitment to ending childhood undernutrition by 2030, should emphasize gender-sensitive programs to accelerate reductions in childhood undernutrition.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data for this study were sourced from Demographic and Health surveys (DHS) and available here: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

References

World Health Organization (WHO), 2022. Fact sheets - Malnutrition. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition. [cited 2022 Jan 16].

World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Organizaiton and World Bank, levels and trends in child malnutrition: key findings of the 2020 edition. in Nutrition and Food Saftey. World Health Organization, Editor; 2020. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/69816/file/Joint-malnutrition-estimates-2020.pdf.

Prendergast AJ, Humphrey JH. The stunting syndrome in developing countries. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2014;34(4):250–65.

Martorell R, Zongrone A. Intergenerational Influences on Child Growth and Undernutrition: Intergenerational influences. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26:302–14.

In Brief to The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 [Internet]. FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO; 2022. Available from: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc0640en. [cited 2022 Dec 31].

John-Joy Owolade A, Abdullateef RO, Adesola RO, Olaloye ED. Malnutrition: an underlying health condition faced in sub Saharan Africa: challenges and recommendations. Ann Med Surg. 2022;82: 104769.

Shrivastava S, Shrivastava P, Ramasamy J. The global public health challenge of malnutrition: ensuring trend reversal. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2017;10(5):1375.

Seife Ayele EAZ, Nisbett N. Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Policy and Programme Design, Coordination and Implementation in Ethiopia. IDS; 2020.

Ministry of Health (MoH) Ethiopia. Seqota Declaration. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.et/site/am/node/170. [cited 2022 Nov 15].

EDHS. Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Central Statistical Agency/Ethiopia and ORC Macro; 2006. 2005.

EPHI and ICF. EPHI ICF. Ethiopia MiniDemographic and Health Survey, 2019 Key indicators Rockville, Maryland, USA: EPHI and ICF 2019 2019.

Asfaw M, Wondaferash M, Taha M, Dube L. Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among children aged between six to fifty nine months in Bule Hora district, South Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):41.

Tesfaw LM, Woya AA. Potential mediators of the link between wealth index and anthropometric indices of under-five children in Ethiopia. Front Public Health. 2022;13(10): 981484.

Muche A, Dewau R. Severe stunting and its associated factors among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia; multilevel ordinal logistic regression model. Ital J Pediatr. 2021;47(1):161.

Sahiledengle B, Mwanri L, Petrucka P, Kumie A, Beressa G, Atlaw D, et al. Determinants of undernutrition among young children in Ethiopia. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):20945.

Wamani H, Åstrøm AN, Peterson S, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T. Boys are more stunted than girls in Sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of 16 demographic and health surveys. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7(1):17.

Roba AA, Assefa N, Dessie Y, Tolera A, Teji K, Elena H, et al. Prevalence and determinants of concurrent wasting and stunting and other indicators of malnutrition among children 6–59 months old in Kersa, Ethiopia. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(3): e13172.

Eshete Tadesse S, Chane Mekonnen T, Adane M. Priorities for intervention of childhood stunting in northeastern Ethiopia: a matched case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9): e0239255.

Haile D, Azage M, Mola T, Rainey R. Exploring spatial variations and factors associated with childhood stunting in Ethiopia: spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16(1):49.

Ayelign A, Zerfu T. Household, dietary and healthcare factors predicting childhood stunting in Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2021;7(4): e06733.

Fantay Gebru K, Mekonnen Haileselassie W, Haftom Temesgen A, Oumer Seid A, Afework MB. Determinants of stunting among under-five children in Ethiopia: a multilevel mixed-effects analysis of 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):176.

Sahiledengle B, Petrucka P, Kumie A, Mwanri L, Beressa G, Atlaw D, et al. Association between water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and child undernutrition in Ethiopia: a hierarchical approach. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1943.

BT Seboka TD Alene HS Ngusie S Hailegebreal DE Yehualashet G Gilano S Variations Determinants of Acute Malnutrition Among Under-Five Children in Ethiopia: Evidence from, et al 2019 Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey Ann Glob Health 87 1 114.

Geda NR, Feng CX, Henry CJ, Lepnurm R, Janzen B, Whiting SJ. Multiple anthropometric and nutritional deficiencies in young children in Ethiopia: a multi-level analysis based on a nationally representative data. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):11.

Paramashanti BA, Benita S. Early introduction of complementary food and childhood stunting were linked among children aged 6–23 months. J Gizi Klin Indones. 2020;17(1):1–8.

Wasting in under five children is significantly varied between rice producing and non-producing households of Libokemkem district, Amhara region, Ethiopia | BMC Pediatrics | Full Text [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 28]. Available from: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-019-1677-2.

Dires S, Mareg M. The Magnitude of wasting and associated factors among children aged 2–5 years in Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BioMed Res Int. 2021;7(2021): e6645996.

Derso T, Tariku A, Biks GA, Wassie MM. Stunting, wasting and associated factors among children aged 6–24 months in Dabat health and demographic surveillance system site: A community based cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):96.

Birhan NA, Belay DB. Associated risk factors of underweight among under-five children in Ethiopia using multilevel ordinal logistic regression model. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21(1):362–72.

Thurstans S, Opondo C, Seal A, Wells J, Khara T, Dolan C, et al. Boys are more likely to be undernourished than girls: a systematic review and meta-analysis of sex differences in undernutrition. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(12): e004030.

Irenso AA, Dessie Y, Berhane Y, Assefa N, Canavan CR, Fawzi WW. Prevalence and predictors of adolescent linear growth and stunting across the urban–rural gradient in eastern Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2020;25(1):101–10.

Mohammed SH, Muhammad F, Pakzad R, Alizadeh S. Socioeconomic inequality in stunting among under-5 children in Ethiopia: a decomposition analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):184.

Yayo NM. Dynamics of inequality in child under-nutrition in Ethiopia. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):182.

Shiferaw N, Regassa N. Levels and trends in key socioeconomic inequalities in childhood undernutrition in Ethiopia: evidence from Ethiopia demographic and health surveys 2000–2019. Discov Soc Sci Health. 2023;3(1):5.

Fenta HM, Tesfaw LM, Derebe MA. Trends and determinants of underweight among under-five children in Ethiopia: Data from EDHS. Int J Pediatr. 2020;29(2020):1–9.

Samuel A, Osendarp SJM, Feskens EJM, Lelisa A, Adish A, Kebede A, et al. Gender differences in nutritional status and determinants among infants (6–11 m): a cross-sectional study in two regions in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):401.

Wang M, Nadolnyak D, Hartarska V. Gender Differences in Child Malnutrition in Ethiopia: Evidence from Three Decomposition Techniques. Res Appl Econ. 2021;13(3):67.

Tesema GA, Tessema ZT, Angaw DA, Tamirat KS, Teshale AB. Geographic weighted regression analysis of hot spots of anemia and its associated factors among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia: A geographic weighted regression analysis and multilevel robust Poisson regression analysis. Blachier F, editor. PLOS ONE. 2021 Nov 4;16(11):e0259147.

Alemu ZA, Ahmed AA, Yalew AW, Birhanu BS. Non random distribution of child undernutrition in Ethiopia: spatial analysis from the 2011 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):198.

Seboka BT, Hailegebreal S, Mamo TT, Yehualashet DE, Gilano G, Kabthymer RH, et al. Spatial trends and projections of chronic malnutrition among children under 5 years of age in Ethiopia from 2011 to 2019: a geographically weighted regression analysis. J Health Popul Nutr. 2022;41(1):28.

Tamir TT, Techane MA, Dessie MT, Atalell KA. Applied nutritional investigation spatial variation and determinants of stunting among children aged less than 5 y in Ethiopia: a spatial and multilevel analysis of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2019. Nutrition. 2022;103–104: 111786.

Jember TA, Teshome DF, Gezie LD, Agegnehu CD. Spatial variation and determinants of childhood anemia among children aged 6 to 59 months in Ethiopia: further analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health survey 2016. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):497.

EDHS. Central Statistical Authority [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. 2001. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Authority and ORC Macro. 2000.

EDHS. Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Central Statistical Agency and ICF International; 2012. 2011.

EDHS. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2016. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF. 2016.

WHO Child Growth Standards, 2006. Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924154693X.

Sunuwar DR, Singh DR, Pradhan PMS. Prevalence and factors associated with double and triple burden of malnutrition among mothers and children in Nepal: evidence from 2016 Nepal demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Tarekegn BT, Assimamaw NT, Atalell KA, Kassa SF, Muhye AB, Techane MA, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of double and triple burden of malnutrition among child-mother pairs in Ethiopia: spatial and survey regression analysis. BMC Nutr. 2022;8(1):34.

Félix-Beltrán L, Macinko J, Kuhn R. Maternal height and double-burden of malnutrition households in Mexico: stunted children with overweight or obese mothers. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(1):106–16.

Kumar P, Chauhan S, Patel R, Srivastava S, Bansod DW. Prevalence and factors associated with triple burden of malnutrition among mother-child pairs in India: a study based on National Family Health Survey 2015–16. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):391.

Bates K, Gjonça A, Leone T. Double burden or double counting of child malnutrition? The methodological and theoretical implications of stuntingoverweight in low and middle income countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(8):779–85.

Determinants of Stunting and Overweight among Young Children and Adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa - Susan Keino, Guy Plasqui, Grace Ettyang, Bart van den Borne, 2014. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/156482651403500203?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed.[cited 2022 Apr 26].

Child stunting concurrent with wasting or being overweight: A 6-y follow up of a randomized maternal education trial in Uganda. 2021;3.

UNICEF. UNICEF Conceptual Framework on Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2021; Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/113291/file/UNICEF%20Conceptual%20Framework.pdf. [cited 2022 May 28].

Gebreegziabher T, Regassa N. Ethiopia’s high childhood undernutrition explained: analysis of the prevalence and key correlates based on recent nationally representative data. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(11):2099–109.

Muche A, Gezie LD, Baraki AG egzabher, Amsalu ET. Predictors of stunting among children age 6–59 months in Ethiopia using Bayesian multi-level analysis. Sci Rep. 2021 Feb 12;11:3759.

Tesfaw LM, Dessie ZG. Multilevel multivariate analysis on the anthropometric indicators of under-five children in Ethiopia: EMDHS 2019. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):162.

Gebreayohanes M, Dessie A. Prevalence of stunting and its associated factors among children 6–59 months of age in pastoralist community, Northeast Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2): e0256722.

Ersino G, Zello GA, Henry CJ, Regassa N. Gender and household structure factors associated with maternal and child undernutrition in rural communities in Ethiopia. Schooling CM, editor. PLOS ONE. 2018 Oct 4;13(10):e0203914.

Ambel, Alemayehu A. and Andrews, Colin and Bakilana, Anne Margreth and Foster, Elizabeth and Khan, Qaiser and Wang, Huihui,. Maternal and Child Health Inequalities in Ethiopia (December 9, 2015). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7508, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2701574.

Amare D, Negesse A, Tsegaye B, Assefa B, Ayenie B. Prevalence of undernutrition and its associated factors among children below five years of age in Bure Town, West Gojjam Zone, Amhara National Regional State. Northwest Ethiopia Adv Public Health. 2016;2016:1–8.

Sewenet T, W/Selassie M, Zenebe Y, Yimam W, Woretaw L. Undernutrition and Associated Factors Among Children Aged 6–23 Months in Dessie Town, Northeastern Ethiopia, 2021: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study. Front Pediatr. 2022 Jul 8;10:916726.

Takele BA, Gezie LD, Alamneh TS. Pooled prevalence of stunting and associated factors among children aged 6–59 months in Sub-Saharan Africa countries: A Bayesian multilevel approach. Augusto O, editor. PLOS ONE. 2022 Oct 13;17(10):e0275889.

Ali Z, Saaka M, Adams AG, Kamwininaang SK, Abizari AR. The effect of maternal and child factors on stunting, wasting and underweight among preschool children in Northern Ghana. BMC Nutr. 2017;3(1):31.

Sinha RK, Dua R, Bijalwan V, Rohatgi S, Kumar P. Determinants of Stunting, Wasting, and Underweight in Five High-Burden Pockets of Four Indian States. Indian J Community Med. 2018 Oct-Dec;43(4):279–283. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_151_18. PMID: 30662180; PMCID: PMC6319291. [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 15]. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/ijcm/Fulltext/2018/43040/Determinants_of_Stunting,_Wasting,_and_Underweight.7.aspx.

Masibo PK, Makoka D. Trends and determinants of undernutrition among young Kenyan children: Kenya Demographic and Health Survey; 1993, 1998, 2003 and 2008–2009. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(9):1715–27.

Mukabutera A, Thomson DR, Hedt-Gauthier BL, Basinga P, Nyirazinyoye L, Murray M. Risk factors associated with underweight status in children under five: an analysis of the 2010 Rwanda Demographic Health Survey (RDHS). BMC Nutr. 2016;2(1):40.

Garenne M, Myatt M, Khara T, Dolan C, Briend A. Concurrent wasting and stunting among under-five children in Niakhar, Senegal. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15(2): e12736.

Moshi CC, Sebastian PJ, Mushumbusi DG, Azizi KA, Meghji WP, Kitunda ME, et al. Determinants of underweight among children aged 0–23 months in Tanzania. Food Sci Nutr. 2022;10(4):1167–74.

Torlesse H, Cronin AA, Sebayang SK, Nandy R. Determinants of stunting in Indonesian children: evidence from a cross-sectional survey indicate a prominent role for the water, sanitation and hygiene sector in stunting reduction. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):669.

Thompson AL. Greater male vulnerability to stunting? evaluating sex differences in growth, pathways and biocultural mechanisms. Ann Hum Biol. 2021;48(6):466–73.

Green MS. The male predominance in the incidence of infectious diseases in children: a postulated explanation for disparities in the literature. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21(2):381–6.

R P. Why is infant mortality higher in boys than in girls? A new hypothesis based on preconception environment and evidence from a large sample of twins. Demography [Internet]. 2013 Apr [cited 2022 May 16];50(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23151996/.

Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, Farrell MH. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(4):302–8.

Steen EE, Källén K, Maršál K, Norman M, Hellström-Westas L. Impact of sex on perinatal mortality and morbidity in twins. J Perinat Med [Internet]. 2014 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Jan 5];42(2). Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/jpm-2013-0147/html.

Galante L, Milan A, Reynolds C, Cameron-Smith D, Vickers M, Pundir S. Sex-specific human milk composition: the role of infant sex in determining early life nutrition. Nutrients. 2018;10(9):1194.

Muenchhoff M, Goulder PJR. Sex differences in pediatric infectious diseases. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(suppl 3):S120–6.

Thurstans S, Opondo C, Seal A, Wells JC, Khara T, Dolan C, et al. Understanding sex differences in childhood undernutrition: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2022;14(5):948.

Agho KE, Akombi BJ, Ferdous AJ, Mbugua I, Kamara JK. Childhood undernutrition in three disadvantaged East African Districts: a multinomial analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):118.

Odei Obeng-Amoako GA, Karamagi CAS, Nangendo J, Okiring J, Kiirya Y, Aryeetey R, et al. Factors associated with concurrent wasting and stunting among children 6–59 months in Karamoja, Uganda. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(1): e13074.

García Cruz L, González Azpeitia G, Reyes Súarez D, Santana Rodríguez A, Loro Ferrer J, Serra-Majem L. Factors associated with stunting among children aged 0 to 59 Months from the Central Region of Mozambique. Nutrients. 2017;9(5):491.

Bukusuba J, Kaaya AN, Atukwase A. Predictors of stunting in children aged 6 to 59 months: a case-control study in Southwest Uganda. Food Nutr Bull. 2017;38(4):542–53.

Simelane MS, Chemhaka GB, Zwane E. A multilevel analysis of individual, household and community level factors on stunting among children aged 6–59 months in Eswatini: a secondary analysis of the Eswatini 2010 and 2014 Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10): e0241548.

Tsega TD, Tafere Y, Ashebir W, Asmare B. Time to breastfeeding cessation and its predictors among mothers who have children aged two to three years in Gozamin district, Northwest Ethiopia: A retrospective follow-up study. Dasvarma GL, editor. PLOS ONE. 2022 Jan 21;17(1):e0262583.

Singh A, Upadhyay AK, Kumar K. Birth size, stunting and recovery from stunting in Andhra Pradesh, India: evidence from the young lives study. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(3):492–508.

Sarma H, Khan JR, Asaduzzaman M, Uddin F, Tarannum S, Hasan MdM, et al. Factors Influencing the Prevalence of Stunting Among Children Aged Below Five Years in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. 2017 Sep;38(3):291–301.

Rina T, Lm A, Ke A. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives: evidence from the 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Pediatr [Internet]. 2014 Sep 27;14. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25262003/. [cited 2022 Jun 7].

Addo OY, Stein AD, Fall CH, Gigante DP, Guntupalli AM, Horta BL, et al. Maternal height and child growth patterns. J Pediatr. 2013;163(2):549–54.

Karlsson O, Kim R, Bogin B, Subramanian S. Maternal height-standardized prevalence of stunting in 67 low- and middle-income countries. J Epidemiol. 2022;32(7):337–44.

Ferreira HS, Moura FA, Cabral CR, Florêncio TMMT, Vieira RC, de Assunção ML. Short stature of mothers from an area endemic for undernutrition is associated with obesity, hypertension and stunted children: a population-based study in the semi-arid region of Alagoas. Northeast Brazil Br J Nutr. 2009;101(8):1239–45.

Khatun W, Alam A, Rasheed S, Huda TM, Dibley MJ. Exploring the intergenerational effects of undernutrition: association of maternal height with neonatal, infant and under-five mortality in Bangladesh. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(6): e000881.

Rahman MHU, Malik MA, Chauhan S, Patel R, Singh A, Mittal A. Examining the linkage between open defecation and child malnutrition in India. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;1(117): 105345.

Cumming O, Cairncross S. Can water, sanitation and hygiene help eliminate stunting? current evidence and policy implications. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(S1):91–105.

Ademas A, Adane M, Keleb A, Berihun G, Tesfaw G. Water, sanitation, and hygiene as a priority intervention for stunting in under-five children in northwest Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Ital J Pediatr. 2021;47(1):174.

Luby SP, Rahman M, Arnold BF, Unicomb L, Ashraf S, Winch PJ, et al. Effects of water quality, sanitation, handwashing, and nutritional interventions on diarrhoea and child growth in rural Bangladesh: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(3):e302–15.

Null C, Stewart CP, Pickering AJ, Dentz HN, Arnold BF, Arnold CD, et al. Effects of water quality, sanitation, handwashing, and nutritional interventions on diarrhoea and child growth in rural Kenya: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(3):e316–29.

Humphrey JH, Mbuya MNN, Ntozini R, Moulton LH, Stoltzfus RJ, Tavengwa NV, et al. Independent and combined effects of improved water, sanitation, and hygiene, and improved complementary feeding, on child stunting and anaemia in rural Zimbabwe: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e132–47.

Bliznashka L, Jeong J, Jaacks LM. Maternal and paternal employment in agriculture and early childhood development: A cross-sectional analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data. Srinivas PN, editor. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023 Jan 6;3(1):e0001116.

Amaha ND, Woldeamanuel BT. Maternal factors associated with moderate and severe stunting in Ethiopian children: analysis of some environmental factors based on 2016 demographic health survey. Nutr J. 2021;20(1):18.

Abuya BA, Ciera J, Kimani-Murage E. Effect of mother’s education on child’s nutritional status in the slums of Nairobi. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12(1):80.

Aprilina HD, Nurkhasanah S, Hisbulloh L. Mother’s nutritional knowledge and behavior to stunting prevalence among children under two years old: case-control. Bali Med J. 2021;10(3):1211–5.

Nshimyiryo A, Hedt-Gauthier B, Mutaganzwa C, Kirk CM, Beck K, Ndayisaba A, et al. Risk factors for stunting among children under five years: a cross-sectional population-based study in Rwanda using the 2015 Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):175.

Darteh EKM, Acquah E, Kumi-Kyereme A. Correlates of stunting among children in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):504.

Chirande L, Charwe D, Mbwana H, Victor R, Kimboka S, Issaka AI, et al. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives in Tanzania: evidence from the 2010 cross-sectional household survey. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):165.

WHO. Social determinants of health. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health. [cited 2023 May 9].

Li H, Yuan S, Fang H, Huang G, Huang Q, Wang H, et al. Prevalence and associated factors for stunting, underweight and wasting among children under 6 years of age in rural Hunan Province, China: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):483.

Aboagye RG, Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Frimpong JB, Archer AG, Adu C, et al. Birth weight and nutritional status of children under five in sub-Saharan Africa. Kumar S, editor. PLOS ONE. 2022 Jun 9;17(6):e0269279.

Woodruff BA, Wirth JP, Ngnie-Teta I, Beaulière JM, Mamady D, Ayoya MA, et al. Determinants of stunting, wasting, and Anemia in Guinean preschool-age children: an analysis of dhs data from 1999, 2005, and 2012. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39(1):39–53.

Yazew T, Daba A. Associated Factors of Wasting among Infants and Young Children (IYC) in Kuyu District, Northern Oromia, Ethiopia. Formanowicz D, editor. BioMed Res Int. 2022 Jun 30;2022:1–8.

Rachmi CN, Agho KE, Li M, Baur LA. Stunting, Underweight and Overweight in Children Aged 2.0–4.9 Years in Indonesia: Prevalence Trends and Associated Risk Factors. PLOS ONE. 2016 May 11;11(5):e0154756.

Das S, Gulshan J. Different forms of malnutrition among under five children in Bangladesh: a cross sectional study on prevalence and determinants. BMC Nutr. 2017;3(1):1.

Bekele SA, Fetene MZ. Modeling non-Gaussian data analysis on determinants of underweight among under five children in rural Ethiopia: Ethiopian demographic and health survey 2016 evidences. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5): e0251239.

Fekadu Y, Mesfin A, Haile D, Stoecker BJ. Factors associated with nutritional status of infants and young children in Somali Region, Ethiopia: a cross- sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):846.

Özaltin E. Association of maternal stature with offspring mortality, underweight, and stunting in low- to middle-income countries. JAMA. 2010;303(15):1507.

Akash Porwal, Praween K Agarwal, Sana Ashraf, Rajib Acharya, Sowmya Ramesh, Nizamuddin Khan, et al. Association of maternal height and body mass index with nutrition of children under 5 years of age in India: Evidence from Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016–18. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2021 Dec 1;30(4).

Kumar R, Abbas F, Mahmood T, Somrongthong R. Prevalence and factors associated with underweight children: a population-based subnational analysis from Pakistan. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7): e028972.

Modjadji P, Madiba S. Childhood undernutrition and its predictors in a rural health and demographic surveillance system site in South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(17):3021.

Nigatu G, Assefa Woreta S, Akalu TY, Yenit MK. Prevalence and associated factors of underweight among children 6–59 months of age in Takusa district, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):106.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Measure DHS Program for providing the DHS datasets.

Funding

No organization funded this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BS contributed to the study design, conceptualization, performed the analysis and drafted the first draft of this manuscript. LM and CB provided technical support and critically reviewed the manuscript. KEA supervised the data analysis, provided technical support and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We used datasets provided by the Demographic Health Surveys programme and have not had any form of contact with the study participants. Informed consent for the present analysis was not necessary because secondary data analysis did not involve interaction with the participants. Ethical clearance for the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) was provided by the Ethiopia Health and Nutrition Research Institute (EHNRI) Review Board, the National Research Ethics Review Committee (NRERC) at the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Institutional Review Board of ICF International, and the CDC. The DHS programme recognizes and adheres to established international and local ethical standards and protocols in its surveys. Further information regarding the DHS data usage and ethical standards can be accessed online (https://dhsprogram.com/data/Access-Instructionscfm). An approval letter for the use of the EDHS data set was gained from MEASURE DHS. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declares that they have no any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahiledengle, B., Mwanri, L., Blumenberg, C. et al. Gender-specific disaggregated analysis of childhood undernutrition in Ethiopia: evidence from 2000–2016 nationwide survey. BMC Public Health 23, 2040 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16907-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16907-x