Abstract

Background

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been growing concern about the declining mental health and healthy behaviors compared to pre-pandemic levels. Despite this, there is a lack of longitudinal studies that have examined the relationship between health behaviors and mental health during the pandemic. In response, the statewide COVIDsmart longitudinal study was launched. The study’s main objective is to better understand the effects of the pandemic on mental health. Findings may provide a foundation for the identification of public health strategies to mitigate future negative impacts of the pandemic.

Methods

Following online recruitment in spring of 2021, adults, ages 18 to 87, filled out social, mental, economic, occupational, and physical health questionnaires on the digital COVIDsmart platform at baseline and through six monthly follow-ups. Changes in the participant’s four health behaviors (e.g., tobacco and alcohol consumption, physical activity, and social media use), along with sex, age, loneliness score, and reported social and economic (SE) hardships, were analyzed for within-between group associations with depression and anxiety scores using Mixed Models Repeated Measures.

Results

In this study, of the 669 individuals who reported, the within-between group analysis indicated that younger adults (F = 23.81, p < 0.0001), loneliness (F = 234.60, p < 0.0001), SE hardships (F = 31.25, p < 0.0001), increased tobacco use (F = 3.05, p = 0.036), decreased physical activity (F = 6.88, p = 0.0002), and both positive and negative changes in social media use (F = 7.22, p = 0.0001) were significantly associated with worse depression scores. Additionally, females (F = 6.01, p = 0.015), younger adults (F = 32.30, p < 0.0001), loneliness (F = 154.59, p < 0.0001), SE hardships (F = 22.13, p < 0.0001), increased tobacco use (F = 4.87, p = 0.004), and both positive and negative changes in social media use (F = 3.51, p = 0.016) were significantly associated with worse anxiety scores. However, no significant changes were observed in the within-between group measurements of depression and anxiety scores over time (p > 0.05). Physical activity was not associated with anxiety nor was alcohol consumption with both depression and anxiety (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the longitudinal changes in behaviors within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings may facilitate the design of preventative population-based health approaches during the COVID-19 pandemic or future pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Numerous studies have demonstrated that COVID-19 has had a negative impact on mental health and has led to increased psychological distress such as anxiety and depression compared to pre-pandemic levels [1,2,3]. There is also a growing body of literature on the relationship between health behaviors and depression and anxiety [4]. Exercise, especially high intensity training, is one of the best health behaviors an individual can adopt to improve physical and mental health [5]. Previous studies reported that an increase in alcohol or tobacco consumptions, as well as a decrease in physical activity, have had a negative impact on mental health during the pandemic [6, 7]. Research on the impact of social media usage on mental health show mixed results, some longitudinal studies reported social media usage as a non-factor, a risk factor, or a protective factor [8,9,10]. During the pandemic, many researchers turned to digital research methods to continue conducting research while mitigating risk of infection. This includes studies of the impacts of COVID-19 on health outcomes [11, 12]. Along with focusing on health safety, digital studies facilitate recruitment of large sample of participants, especially those that live in rural areas [13]. They also reduce the cost and participant burden for collecting multiple waves of data over a short time period.

Using digital research methods, the COVIDsmart longitudinal study aimed to evaluate the relationship between COVID-19-related health behaviors and the mental health of individuals in Virginia. By examining this relationship, this study sought to shed light on the significance of personalized health promotion initiatives during a pandemic.

Methods

COVIDsmart was an online statewide study developed in collaboration with Eastern Virginia Medical School-Sentara Healthcare Analytics and Delivery Science Institute, George Mason University, and Vibrent Health Inc. Data were collected using an online platform in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) [14, 15]. Participants received email invitations to join the COVIDsmart platform and complete a series of questionnaires. Demographic data was collected at baseline, and participants’ personal experiences impacted by COVID-19, mental health and behaviors, and COVID-related occupational experiences were collected at baseline and at each of the six monthly follow-ups [16, 17]. Specifically, the present study evaluated the participant’s sex, age, a sum of the social and economic (SE) hardships experienced (i.e., lost income from a job or business, job loss, unable to get groceries, etc.) (Appendix A) [18], as well as validated measures of depression (using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 or PHQ-9) [19], anxiety (using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 or GAD-7), [20] and loneliness (using a shortened version of the University of California Los Angeles Loneliness scale) [21]. Additionally, the participants’ changes in health behaviors such as alcohol and tobacco consumption, physical activity, and social media use (such as Facebook or Twitter) were also evaluated. Participants were asked whether their behaviors have increased, decreased, approximately stayed the same, or were not applicable (N/A) in the past two weeks (Appendix B).

Study participants

Recruitment strategies and processes have been detailed by Schilling et al. [14] and Bartholmae et al. [15]. Briefly, marketing tools such as radio, television, emails, newsletters, and social media were employed to invite residents of Virginia. Recruitment occurred from March to May 2021, and data was collected from March to November 2021. Inclusion criteria included being a resident of Virginia, United States, between the 18 and 87 years of age, proficient in English, and had access to the internet via a personal email account or a mobile phone number. Eligible participants were sent a digital consent form to join the study. A total of 782 participants (N = 782) gave informed consent to participate in the study. To encourage continuous engagement, participants who completed the questionnaires at each of the six monthly follow-ups had a 1 in 20 chance of winning a $50 gift card each month. At the end of the study, active participants had a 1 in 4 chance of winning a $500 gift card [15].

Statistical analysis

The study conducted descriptive statistics on several factors such as participants' demographics, health behaviors, loneliness, reported number of SE hardships, and their depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) scores. Mixed Models Repeated Measures (MMRM) were used to evaluate the changes in behaviors over the six months and their association with the outcomes, depression and anxiety. The demographics collected at baseline were included in the MMRM as covariates. Independent variables, (loneliness, SE hardships, and heath behaviors) and dependent variables (depression and anxiety) included in the MMRM were collected at baseline and follow-ups one through six. Within-between group comparisons were evaluated across all time points of the study. Additional bivariate analyses were conducted between significant independent variables from the MMRM analyses at each time point of the study. Mann–Whitney U tests were used to measure the differences between males’ and females' depression and anxiety scores. Spearman's correlation was used to measure the association between age, the loneliness scale score, and the number of SE hardships with depression and anxiety scores. Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to measure the difference in the depression and anxiety scores among participants who reported changes in health behaviors such as alcohol, tobacco, physical activity, and social media in the past two weeks. Post-hoc tests were conducted using the Dwass, Steel, Critchlow-Fligner (DSCF) method in cases where the Kruskal–Wallis test found a significant difference in mental health outcome among the health behaviors. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Demographics

Out of the 782 participants who consented to be in the study, 669 participants have completed the questionnaires on their mental health at baseline in the COVIDsmart study. Of these participants’ demographics described in Table 1, most were female (78.30%), middle aged (µ = 50.54, SD = 14.44), non-Hispanic White (94.70%), have earned a post-secondary degree (80.88%), and annually earn at least $50,000 (88.20%). Most participants lived in a two-person household (37.70%) and lived with their married or unmarried partner (68.90%).

Also described in Table 1, initially, 669 participants completed the questionnaires at baseline but, only 66.40% of the participants (n = 444) had reported at the first follow-up. Subsequently, monthly follow-up completion rates declined, with 53.70% (n = 359), 44.50% (n = 298), 37.20% (n = 249), and 35.30% (n = 236) completing follow-ups two, three, four, and five, respectively. At the final follow-up, 212 (31.70%) of the original 669 participants had completed all six follow-ups. A detailed table for screening and eligibility rates was published previously by Schilling et al. [14]. However, the proportion of most of the demographic groups remained relatively the same throughout the study, p > 0.05, except the mean age had increased at each follow-up (p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

Mixed models repeated measures

The MMRM (Table 2) estimated the impact of various demographic, behavioral, social, and economic factors on the depression (PHQ-9) scores of study participants over a period of time. The within-between group results demonstrated that age (F = 23.81, df = 1, p < 0.0001), COVID-19 related SE hardships (F = 31.25, df = 1, p < 0.0001), loneliness (F = 234.60, df = 1, p < 0.0001), tobacco use (F = 3.05, df = 3, p = 0.036), physical activity (F = 6.88, df = 3, p = 0.0002), and social media use (F = 7.22, df = 3, p = 0.001) were all significantly associated with depression scores. However, sex (F = 3.67, df = 1, p = 0.056), alcohol use (F = 1.18, df = 3, p = 0.316), and time (F = 0.98, df = 6, p = 0.435) did not significantly impact the participants’ depression scores. None of the within-between group comparisons over time were statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Another MMRM (Table 2) estimates the impact of the same list of independent factors on the participants’ anxiety (GAD-7) scores over a period of time. The within-between group results demonstrated that sex (F = 6.01, df = 1, p = 0.015), age (F = 32.30, df = 1, p < 0.0001), COVID-19 related SE hardships (F = 22.13, df = 1, p < 0.0001), loneliness (F = 154.59, df = 1, p < 0.0001), tobacco (F = 3.51, df = 3, p = 0.016), and social media (F = 3.51, df = 3, p = 0.016) were all significantly associated with anxiety scores. However, alcohol (F = 1.32, df = 3, p = 0.268), physical activity (F = 1.14, df = 3, p = 0.331), and time (F = 1.14, df = 6, p = 0.331) did not impact the anxiety scores. Additionally, none of the within-group comparisons over time were found not to be statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Depression (PHQ-9)

Following the results of the MMRM, a series of Spearman’s correlations revealed that participant’s age had weak negative correlation to their depression (PHQ-9) scores at all time points (p < 0.0001). Similarly, Spearman’s correlations revealed that the participant’s loneliness was strongly, positively correlated with their depression scores at all time points (p < 0.0001). Additionally, the participant’s reported SE hardships were weakly to moderately, positively correlated with their depression scores at all time points (p < 0.0001) (Table 3).

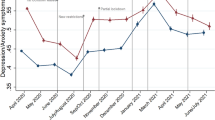

The Kruskal–Wallis tests overall have found significant associations with changes in tobacco consumption and the participant’s depression (PHQ-9) scores at baseline (χ2 = 14.22, p = 0.003), follow-up one (χ2 = 10.78, p = 0.013), follow-up two (χ2 = 9.33, p = 0.025), follow-up four (χ2 = 8.95, p = 0.030), and follow-up six (χ2 = 11.44, p = 0.010). The following the post-hoc DSCF pairwise comparison also revealed that participants who reported an increase in tobacco consumption in the last two weeks also reported higher average depression compared to those who responded with approximately the same or “N/A” (Fig. 1).

Another series of Kruskal–Wallis tests indicated an association between the changes in the participant’s physical activity in the last two weeks and the depression (PHQ-9) scores at baseline (χ2 = 56.50, p < 0.0001), follow-up two (χ2 = 16.75, p = 0.001), follow-up three (χ2 = 25.22, p < 0.0001), and follow-up five (χ2 = 10.81, p = 0.013). The post hoc DSCF method also revealed that participants who reported decreased physical activity had higher depression scores compared to participants whose activity increased or remained approximately the same (Fig. 1).

Regarding the effect of social media and the participant’s depression (PHQ-9) scores, the Kruskal Wallis tests reported a significant association at baseline (χ2 = 35.00, p < 0.0001), follow-up one (χ2 = 14.40, p = 0.002), follow-up three (χ2 = 13.70, p = 0.003), follow-up four (χ2 = 16.55, p = 0.001), and follow-up five (χ2 = 12.38, p = 0.006). The DSCF post hoc tests indicated that participants who reported an increase or a decrease in social media use also reported higher depression scores compared to those who remained approximately the same. However, at some follow-ups, only those who responded with decreased social media use were associated with higher depression scores (Fig. 1).

Anxiety (GAD-7)

The Spearman’s correlations have revealed that age had a weak negative correlation with the participant’s anxiety (GAD-7) scores (p < 0.0001). Similarly, significant Spearman’s correlations have found that loneliness was positively, moderately correlated with the anxiety scores (p < 0.0001). And finally, COVID-19 related SE hardships were also significantly and positively, albeit weakly, correlated with the participant’s anxiety scores (p < 0.0001) Table 3.

The participants who reported an increase in tobacco consumption in the last two weeks also reported higher average anxiety at baseline (χ2 = 21.23, p < 0.0001), follow-up one (χ2 = 13.01, p = 0.005), follow-up two (χ2 = 10.29, p = 0.016), follow-up three (χ2 = 8.50, p = 0.037), and follow-up six (χ2 = 11.23, p = 0.011). The post hoc DSCF test generally indicated that participants who reported increased tobacco consumption in the past two weeks had higher anxiety scores compared to those whose consumption remained approximately the same or responded with “N/A” (Fig. 2).

Regarding the effect of social media and the participant’s anxiety (GAD-7) scores, the Kruskal Wallis tests have found a significant association at baseline (χ2 = 33.79, p < 0.0001), follow-up one (χ2 = 11.90, p = 0.007), follow-up three (χ2 = 166.02, p = 0.001), follow-up four (χ2 = 9.81, p = 0.020), and follow-up five (χ2 = 12.53, p = 0.006). Similar to the models with depression (PHQ-9) scores, the DSCF post hoc tests also revealed that both participants who reported an increase or a decrease in social media use in the past two weeks had higher anxiety scores compared to participants who remained approximately the same. However, the reported associations were not consistent as at some time points, decreased social media use was linked with higher anxiety scores, whereas at other time points, only increased social media use indicated higher scores (Fig. 2).

Sex also played a role in the reported anxiety scores with the Mann–Whitney U tests have indicated that female participants reported significantly higher average anxiety scores than males at baseline (U = 38,395.50, p < 0.0001), follow-up one (U = 15,331.00, p < 0.0001), follow-up two (U = 11,108.50, p = 0.005), follow-up three (U = 7954.00, p = 0.018), follow-up four (U = 5364.00, p = 0.002), follow-up five (U = 5323.00, p = 0.026), and follow-up six (U = 3777.00, p = 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, we examined the effect of changes in alcohol consumption on mental health because alcohol is often used as a coping mechanism following a stressful event, despite its association with negative mental health [22]. However, the present study did not find a statistically significant association between changes in alcohol consumption and an increase in depression or anxiety over the course of the study. This may be due to the fact that majority of the COVIDsmart participants were well-educated white women with higher income, who, as reported by previous literature, are associated with lower rates of alcohol consumption and are therefore less likely to engage in heavy drinking or develop alcohol use disorders when coping with stressors [23,24,25,26]. For example, Probst et al. [23] reported in a meta-analysis that socioeconomically disadvantaged populations with low education and/or income were associated with higher relative risk of alcohol-attributable mortality. Higher socioeconomic factors, such as high income and higher educational attainment, as seen in this study, are examples of social determinants of health with protective factors against alcohol consumption.

Increased tobacco consumption was found to be significantly associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. This finding is consistent with previous research, as Stanton et al. [7] also reported a positive association between an increase in tobacco consumption and a higher risk of depression and anxiety compared to those who reported no change or a decrease in tobacco consumption. These findings coincide with the American Lung Association and the Mental Health Foundation on the important implications for healthcare professionals and policymakers on the need to address the negative impact of tobacco use on mental health [27, 28]. It is essential to develop effective strategies to help individuals reduce or quit tobacco use, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, where the negative impact of tobacco use on respiratory health may be compounded [29]. Additionally, these findings suggest that assessing an individual's tobacco use can provide insight into their risk of developing depression and anxiety. Therefore, it may be valuable to screen for tobacco use during mental health assessments.

In the current study, a decrease in physical activity was found to be associated with higher depression. These findings are similar to other studies the reported the positive effect of exercising on the mental well-being of an individual, including reducing symptoms of depression [7, 30, 31]. Specifically, a systematic review of reviews with meta-analysis published by Singh et al. [30] reported that physical activity reduced depression, especially accounting for the different types of exercise, session duration, and frequency per week. Different from current literature, this study did not find changes in physical activity to be associated with anxiety. Both Singh et al. [30] and Wanjau et al. [31] reported positive effects of physical activity on anxiety, in addition to the effect on depression. The COVIDsmart study may have encountered some external factors not included in the analysis that may confound the anxiety outcomes.

With social media becoming more ubiquitous in maintaining social relationships, researchers have been investigating its use and its potential impact on mental health in both the short- and long-term. Several studies have examined the relationship between social media use and depression and anxiety among adults [8, 32,33,34]. A meta-analysis by Lee et al. [35] found that overall, increased social media use (i.e., Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) was linked to anxiety and depressive symptoms among young adults. This meta-analysis reported that COVID-19 may exacerbate existing mental health disorders that cause depression and anxiety among young adults [35]. In contrast, the middle-aged adults in the COVIDsmart study reported either an increase or decrease in social media use had higher depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) scores compared to those whose use remained relatively stable. These findings are inconclusive but consistent with a non-COVID-19 related systematic review, which reported mixed results regarding the association between social media use and depression or anxiety among emerging adults and adolescents [8]. However, a systematic review by Karim et al. [8] identified a few studies, that focused on either adolescents, young adults, or adults, that did not find a significant association between increased social media use and mental health issues. Nevertheless, they also reported that many other studies did report any positive association [8]. One study suggested that social media use could be a risk factor for emotional dysregulation and perceived stress, but also a coping tool for dealing with mental health crises [34]. However, this study once again focused only on adolescents and young adults. Overall, the present study and the existing literature have reported conflicting results regarding the impact of social media use on mental health. Additional research using validated tools is necessary to identify which aspects and duration of social media use, specifically among middle-aged and older adults, and what are the risk or protective factors.

However, health behaviors rarely occur in a vacuum and are often products of other stressors such as loneliness and SE factors. The COVIDsmart study found that participants who reported an increased number of SE hardships as well as loneliness were also more likely to report higher depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) scores. These results support the current literature that lonely individuals are less likely to improve health behaviors in such as tobacco and alcohol cessation, and additionally, loneliness has been linked to poorer mental health [36, 37]. Similarly, environmental stressors such as poor financial stability and poor health behaviors are interlinked where tobacco and alcohol consumption are often seen as coping mechanisms for stress and psychological distress [38, 39]. Social media use can have a varying impact of mental health where decreasing usage can exacerbate loneliness for individuals who struggle with maintaining online relationships, whereas increasing usage could also mitigate loneliness [40, 41]. However, Hampton et al. [40] also described that an increase in social media usage can introduce additional stressors such as reading negative news articles. Additionally, changes in health behaviors over time may be due to environmental changes at the personal, family, community, or policy levels, for example, losing a job, health status of family members, or community and national restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Given that certain health behaviors, namely tobacco use, physical activity, and social media, are linked with an individual’s mental health, there should be a concerted effort to better disseminate accessible resources to help maintain positive health behaviors. Public health and community leaders should encourage individuals to access the many free resources online that can help stave off tobacco use, maintain physical activity, and manage healthy social media usage [42,43,44,45,46]. Additionally, these individuals can also utilize these on how to cope with stress using information from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention or from the National Alliance on Mental Illness [47, 48]. Not only are healthy behaviors linked to better mental health outcomes, they also improve physical health, extend life expectancy, reduce risk of morbidity later in life, and gain financial stability [49].

The COVIDsmart study has a few strengths; no other studies have observed participants over a course of time to measure the longitudinal effect of health behaviors on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, this HIPAA compliant online platform allowed for this study to occur during the social restrictions of the pandemic. However, it is also important to acknowledge its limitations. Firstly, the data collected relied on self-reported measures of health behaviors, depression, and anxiety, which may be influenced by reporting biases. Secondly, although multiple recruitment strategies were utilized to capture racial and ethnic minorities and vulnerable populations with low socioeconomic status, most participants were white, higher income, and highly educated with at least a Master’s degree [15]. The lack of racial and ethnic diversity and socioeconomic backgrounds limits this study, however, this is a common limitation with digital studies, as observed in other research studies [50]. Therefore, future studies should aim to capture a more diverse population. Thirdly, the study experienced a high rate of loss to follow-up, which may have been influenced by numerous factors such as decreased concern with COVID-19 following the easement of restrictions and availability of vaccines in 2021. Finally, the study's questions did not concretely measure changes in health behaviors such as the number of packs of cigarettes smoked, alcoholic beverages consumed, or the duration of physical activities done in the past two weeks, and therefore, future studies should aim to include discrete measurements when recording changes of health behaviors.

Conclusions

The COVIDsmart study reveals that changes in health behaviors such as increased alcohol consumption, decreased physical activity, and social media use were associated with higher depression and/or anxiety scores among Virginians. These negative changes in behavior could be a response to the unprecedented environmental, social, and economic stressors caused by the pandemic. Continual monitoring of the effect of health behaviors on mental health is necessary to better understand the indirect consequences of the pandemic on mental health. These results have the potential to assist public health leaders to better understand behavioral changes during a pandemic to better tailor population-based health approaches to promote healthy behaviors. Adopting these healthy behaviors will promote better mental and physical health outcomes now and later in life.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the data governance agreement between us and our partners, GMU and Vibrent Health Inc but are available from the corresponding author, SD, on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SE:

-

Social and economic

- HIPAA:

-

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

- N/A:

-

Not applicable

- MMRM:

-

Mixed Model(s) with Repeated Measures

- DSCF:

-

Dwass, Steel, Critchlow-Fligner

References

Robinson E, Sutin AR, Daly M, Jones A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:567–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098.

Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4.

McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(1):93–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.9740.

Craft LL, Perna FM. The benefits of exercise for the clinically depressed. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(3):104–11. https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v06n0301.

Borrega-Mouquinho Y, Sánchez-Gómez J, Fuentes-García JP, Collado-Mateo D, Villafaina S. Effects of high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity training on stress, depression, anxiety, and resilience in healthy adults during coronavirus disease 2019 confinement: a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychol. 2021;12:643069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643069. Published 2021 Feb 24.

Caroppo E, Mazza M, Sannella A, Marano G, Avallone C, Claro AE, et al. Will nothing be the same again?: changes in lifestyle during COVID-19 pandemic and consequences on mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168433.

Stanton R, To QG, Khalesi S, Williams SL, Alley SJ, Thwaite TL, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114065.

Karim F, Oyewande AA, Abdalla LF, Chaudhry Ehsanullah R, Khan S. Social media use and its connection to mental health: a systematic review. Cureus. 2020;12(6):e8627. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8627.

Feder KA, Riehm KE, Mojtabai R. Is there an association between social media use and mental health? the timing of confounding measurement matters-reply. JAMA Psychiat. 2020;77(4):438. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4503. PMID: 31940005.

Coyne SM, Rogers AA, Zurcher JD, Stockdale L, Booth M. Does time spent using social media impact mental? an eight year longitudinal study. Comput Human Behav. 2020;104:106160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160.

De Man J, Campbell L, Tabana H, Wouters E. The pandemic of online research in times of COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e043866. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043866.

De’ R, Pandey N, Pal A. Impact of digital surge during Covid-19 pandemic: a viewpoint on research and practice. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;55:102171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102171.

Bailey J, Mann S, Wayal S, Hunter R, Free C, Abraham C, et al. Sexual health promotion for young people delivered via digital media: a scoping review. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015. (Public Health Research, No. 3.13.) Chapter 7, Digital research methods and optimum research methodology to evaluate digital interventions. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326976/?report=classic

Schilling J, Klein D, Bartholmae MM, Shokouhi, Toepp AJ, Roess A, et al. COVIDsmart: a digital health initiative for remote data collection and study of COVID’s impact on the state of Virginia. JMIR Form Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.2196/37550.

Bartholmae MM, Roess AA, Renshaw KD, Levy BL, Karpov MV, Sill JM, et al. Evaluation of recruitment strategies on inclusiveness of populations at risk for health disparities in the statewide remote online COVIDsmart registry. VJPH. 2022;7(1):11–45. Available from: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/vjph/vol7/iss1/5/.

Kluge HHP, Jakab Z, Bartovic J, D’Anna V, Severoni S. Refugee and migrant health in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;395:1237–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30791-1.

Liem A, Wang C, Wariyanti Y, Latkin CA, Hall BJ. The neglected health of international migrant workers in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:E20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30076-6.

Ballew MT, Bergquist P, Goldberg M, Gustafson A, Kotcher J, Marlon J, et al. Americans’ risk perceptions and emotional responses to COVID-19. PsyArXiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/au9sd.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093.

Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26(6):655–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574.

Merrill JE, Thomas SE. Interactions between adaptive coping and drinking to cope in predicting naturalistic drinking and drinking following a lab-based psychosocial stressor. Addict Behav. 2013;38(3):1672–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.10.003.

Probst C, Roerecke M, Behrendt S, Rehm J. Socioeconomic differences in alcohol-attributable mortality compared with all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(4):1314–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu043.

Cerdá M, Johnson-Lawrence VD, Galea S. Lifetime income patterns and alcohol consumption: investigating the association between long- and short-term income trajectories and drinking. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(8):1178–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.025.

Tembo C, Burns S, Kalembo F. The association between levels of alcohol consumption and mental health problems and academic performance among young university students. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178142. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178142.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Men's Health and Alcohol Use. Cdc.gov. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/mens-health.htm. [Cited 2023 Apr 3].

American Lung Association. Behavioral Health and Tobacco Use. Lung.org. Available from: https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/smoking-facts/impact-of-tobacco-use/behavioral-health-tobacco-use#:%7E:text=It%20is%20estimated%20that%2035,all%20U.S.%20adult%20cigarette%20consumption.&text=Despite%20the%20national%20cigarette%20smoking,with%20a%20behavioral%20health%20disorder. [Cited 2023 Apr 3].

Mental Health Foundation. Smoking and mental health. Mentalhealth.org.uk. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/a-z-topics/smoking-and-mental-health#:%7E:text=Some%20people%20smoke%20as%20'self,it%20reduces%20stress%20and%20anxiety. [Cited 2023 Mar 24].

Baker J, Krishnan N, Abroms LC, Berg CJ. The impact of tobacco use on covid-19 outcomes: a systematic review. J Smok Cessat. 2022;2022:5474397. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5474397.

Singh B, Olds T, Curtis R, Dumuid D, Virgara R, Watson A, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic review. BJSM. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-106195.

Wanjau MN, Möller H, Haigh F, Milat A, Hayek R, Lucas P, et al. Physical activity and depression and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of reviews and assessment of causality. AJPM Focus. 2023;2(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focus.2023.100074

Zhao N, Zhou G. Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: moderator role of disaster stressor and mediator role of negative affect. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2020;12(4):1019–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12226.

Singh P, Cumberland WG, Ugarte D, Bruckner TA, Young SD. Association between generalized anxiety disorder scores and online activity among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional analysis. JMIR. 2020;22(9):e21490. https://doi.org/10.2196/21490.

Rasmussen EE, Punyanunt-Carter N, LaFreniere JR, Norman MS, Kimball TG. The serially mediated relationship between emerging adults’ social media use and mental well-being. Comput Human Behav. 2020;102:206–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.019.

Lee Y, Jeon YJ, Kang S, Shin JI, Jung YC, Jung SJ. Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in young adults: a meta-analysis of 14 cross-sectional studies. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):995. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13409-0.

Kobayashi LC, Steptoe A. Social isolation, loneliness, and health behaviors at older ages: longitudinal cohort study. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(7):582–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kax033.

Mushtaq R, Shoib S, Shah T, Mushtaq S. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? a review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(9):01–4. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828.

Pampel FC, Krueger PM, Denney JT. Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:349–70. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102529.

Ryu S, Fan L. The relationship between financial worries and psychological distress among U.S. adults [published online ahead of print, 2022 Feb 1]. J Fam Econ Issues. 2022;1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09820-9

Hampton K, Rainie L, Lu W, Shin I, Purcell K. Social media and the cost of caring. Pew Research Center. 2014. 44 p. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/01/15/social-media-and-stress/. [Published 2015 Jan 15; cited 2023 Feb 9]

Latikka R, Koivula A, Oksa R, Savela N, Oksanen A. Loneliness and psychological distress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: relationships with social media identity bubbles. Soc Sci Med. 2022;293:114674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114674.

Quitting Starts Now Make Your Quit Plan. National Cancer Institute. Available from: https://smokefree.gov/build-your-quit-plan. [Cited 2023 Jan 26]

Faseru B, Fagan P, Okuyemi KS. Additional benefits of maintaining a healthy lifestyle after quitting smoking. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2232784. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.32784.

Benefits of cutting down or giving up alcohol. Health Service Executive. Available from: https://www2.hse.ie/living-well/alcohol/health/improve-your-health/benefits-of-cutting-down-giving-up/. [Updated 2022 Sep 23; cited 2023 Feb 2]

How to Be Physically Active While Social Distancing. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/how-to-be-physically-active-while-social-distancing.html. [Updated 2022 Apr 26; cited 2023 Jan 26]

Huff C. Media overload is hurting our mental health. Here are ways to manage headline stress. Monit Psychol. 2022;58(8):20. [cited 2023 Jan 26].

Coping with Stress. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/stress-coping/cope-with-stress/index.html#:~:text=Take%20breaks%20from%20news%20stories,computer%20screens%20for%20a%20while. [updated 2023 Jan 3; cited 2023 Jan 26]

Managing Stress. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Available from: https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Individuals-with-Mental-Illness/Taking-Care-of-Your-Body/Managing-Stress. [Cited 2023 Feb 1]

Benefits of Physical Activity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health/index.htm#:~:text=Regular%20physical%20activity%20is%20one,ability%20to%20do%20everyday%20activities. [updated 2022 Jun 16; cited 2023 Feb 2]

Nelson LM, Simard JF, Oluyomi A, Nava V, Rosas LG, Body M, Linos E. US public concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic from results of a survey given via social media. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):1020–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1369.

Acknowledgements

Angela Toepp, Sarah DePerrior, Josh Edwards, Katie Maney, Amy Adams, Doug Gardner, Julie Suedmeyer-Buller, Mary Westbrook, Praduman Jain, Scott Sutherland, Jack Burtch, Dave Klein, Josh Schilling, Alison Young, and Pearson Brown.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MVK performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. MMB, DS, BLL, AAR, KDR, and JMS critically reviewed the manuscript. MMB prepared Figs. 1 and 2. SD is the Principal Investigator of the study and was responsible for the successful completion of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants gave Informed consent to participate in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Eastern Virginia Medical School institutional review board and was conducted in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix A.

Social and economic hardships questions and responses at baseline and six follow-ups. Appendix B. Questions and responses on the changes in alcohol consumption, tobacco consumption, physical activity, and social media use.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Karpov, M.V., Bartholmae, M.M., Levy, B.L. et al. Exploring the influence of behavioral factors on depression and anxiety scores during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from the Virginia statewide COVIDsmart longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 23, 1749 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16614-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16614-7