Abstract

COVID-19 mitigation measures such as lockdown and social distancing could have a negative impact on mental health. Understanding their impact is essential to minimize adverse effects on individuals, families, and communities. This longitudinal study aimed to evaluate the emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and social isolation in the Argentinian population over time. An online survey evaluating anxiety and depression symptoms, positive affect, and negative affect, was completed by 3,833 people at three different time points: immediately after the lockdown began, 12–15 days after the first assessment, and after 47–51 days. Various socio-demographic factors were considered. A series of mixed repeated-measures ANOVAs were performed, with results showing significant increases over time (with small effect sizes) in anxiety, depression, negative affect, and a decrease in positive affect. Some socio-demographic factors such as age, gender, number of children, and educational level differentially affected these changes. These results suggest that mental health and quality of life were negatively affected, making it essential to monitor emotional distress and other mental health problems in the population and encourage the implementation of support and containment devices to cope with these adverse effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. At this time, more than 100 countries implemented preventive measures, such as full or partial lockdown, physical distancing, self-care recommendations (hygiene), and the use of masks, among others (or a combination of some of these measures). In Europe, most countries have had a period of national lockdown. In Asia and Oceania, some countries have adopted either national or local lockdowns, and others have adopted recommendations on physical distancing or hybrid approaches. Different measures were established in America; for example, Brazil opted for a localized lockdown, whereas Uruguay opted for national recommendations (Dunford et al., 2020).

On March 20, the Argentinian government declared strict isolation measures that reached the entire country. Except for people who worked in essential activities and/or provide basic services (i.e., essential workers) people had to stay at home and could only go out to buy supplies (e.g., food, medicines). These initial measures also included schools and daycare closures. Unlike other countries, isolation was established at an early stage aiming to strengthen the health system (i.e., gathering supplies, freeing up hospital therapy beds, training human resources). From April 18 to June 4, each Argentinian province was allowed to cease mandatory isolation on the condition of establishing protocols to guarantee physical distancing.

The COVID-19 pandemic, as well as those measures proposed to control the spread of the disease (Hawryluck et al., 2004), could lead to adverse cascade effects on mental health (Daks et al., 2020) due to worries about one's health and that of loved ones, economic disruption and losses, challenges in meeting basic needs, lifestyle disruptions, school closures and extended periods of loneliness, among others. These worries could increase with a pronounced multiplication of cases, along with inadequate information provided by the media (Serafini et al., 2020; Shanahan et al., 2020). This context could induce emotional distress and increase anxiety, depressive symptoms, uncertainty, discomfort, and perceived loss of control (Brooks et al., 2020).

Studies about previous epidemics involving quarantines reported worsening in mental health (see Brooks et al., 2020), and results during the COVID-19 pandemic are in accordance with these results (de Quervain et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). People who were in isolation experienced a greater number of psychological symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, sleep problems, irritability, anger, confusion, distress, and post-traumatic stress (Serafini et al., 2020). Some studies even suggested lasting effects after the quarantine ended (Liu et al., 2012).

Longitudinal studies about the COVID-19 pandemic have gradually emerged (e.g., Breslau et al., 2021; Daly et al., 2020). COVID-Minds Network brings together approximately 120 longitudinal studies around the world, synthesizing the main findings regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in five points: (a) Mental health and wellbeing have worsened in comparison to pre-pandemic levels; (b) mental health and wellbeing could potentially return to pre-pandemic levels as lockdown restrictions are gradually eliminated; (c) COVID-19 is not affecting all people in the same way; young adults (18–25 years old), children, women, minority groups, individuals with pre-existing problems, people living alone or people in socioeconomic adversity experience worse psychological responses; (d) healthy habits declined during the pandemic; (e) sleep is an important mediator of levels of stress, depression, and anxiety.

Research conducted in countries with an early spread of COVID-19 has revealed a broad psychological impact (Lima et al., 2020). As reported, psychological symptoms may emerge in individuals without previous mental disorders or worsen in those with pre-existing psychological conditions. Anguish may emerge or increase among infected people or their caretakers (Kelvin & Rubino, 2020). In addition, quarantine can elicit severe distress among people, consequently increasing the risk of hopelessness (Serafini et al., 2020) and suicide rates (Goyal et al., 2020). Moreover, previous studies reported that some socio-demographic factors moderate the psychological impact of quarantine. For example, Taylor et al. (2008) found that gender, age, number of children, and educational level, were related to the psychological effect of quarantine. However, other studies (e.g., Hawryluck et al., 2004) indicate that demographic factors such as marital status, age, educational level, living with other adults, and having children were not associated with psychological effects during quarantine. It is worth mentioning that the majority of the studies were conducted in high-income countries. Low and middle-income countries are often under-represented in empirical studies; therefore, it is necessary to explore how isolation may affect mental health in low and middle-income countries –such as Argentina.

To evaluate the emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and social isolation on mental health, we conducted a longitudinal study consisting of three waves of assessment of anxiety, depression, negative affect, and positive affect. According to both the literature and longitudinal studies reported so far, these dimensions could be compromised in this context. We propose two hypotheses: (a) changes in affective variables intensify as a function of time, showing increases in depressive and anxious symptoms, and (b) these changes will be more pronounced in groups that previous longitudinal COVID-19 studies have identified as vulnerable such as women and young adults.

Methods

Participants

A total of 3,833 participants took part in the three waves of the study. For the statistical analysis, those who answered only one or two of the surveys were removed. Inclusion criteria were to be over 18 years old, live in Argentina, and not suffer from severe physical or psychological diseases. The first survey was answered by 16,514 people. From this survey, a mail list was compilated with all participants that agreed to be included. After 12–15 days, using that list, we reached the participants again, from which 7,336 answered the second survey (44.4% of the original sample). When the third survey was sent, 5,171 people answered it (31.3% of the original sample). We then removed all participants except those who responded to all three instances to allow establishing comparisons. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1.

Instruments

Depression

The Argentinian adaptation (Brenlla & Rodríguez, 2006) of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) was used. The BDI-II is a self-report measure of 21 items that assess the presence and severity of depressive symptoms (e.g., sadness, guilt, pessimism). Participants respond to each item on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores representing higher severity of the symptom. Item 9 (suicidal ideation) was omitted following the recommendation of the Ethics Committee that evaluated this study due to the potential risk it might imply in online surveys. Cronbach's α in the current study (excluding item 9) was 0.96.

Anxiety

The Argentinian adaptation (Leibovich de Figueroa, 1991) of the Spanish version (Spielberger et al., 1999) of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger et al., 1970) was used. Only the state-anxiety dimension was used for the present study, which is composed of 20 items that must be answered on a 4-point Likert scale. Cronbach's α in the current study was 0.91.

Positive and Negative Affect

The Argentinian adaptation (Moriondo et al., 2012) of the Spanish version (López-Gómez et al., 2015) of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) was used. The PANAS includes two subscales, Positive Affect and Negative Affect, each composed of 10 items such as "tense", "nervous", or "satisfied". The participant must indicate whether she/he is feeling that way at that moment, rating each item on a 5-point Likert scale. In the present study, Cronbach's α was 0.97 for the Positive Affect subscale and 0.95 for the Negative Affect subscale.

Socio-Demographic Factors

A structured questionnaire was used to gather information regarding: (a) Self-perceived degree of quarantine compliance, (b) Age, (c) Gender, (d) Variation in economic income due to quarantine, (e) Educational level, (f) Number of children, (g) Whether the respondent has or not dependent older adults, and (h) Total news hours per day. The presence of severe physical or psychological diseases was evaluated through a question included in this questionnaire.

Procedure and Ethical Considerations

Data collection was performed by employing a Google Forms survey. The first freely accessed survey was disseminated by social networks (Facebook and WhatsApp) using a snowball sampling procedure between March 22 and 25 (Time 1 = T1), close to the beginning of isolation measures in Argentina (see Fig. 1). Twelve to fifteen days later (between April 3 and 9, depending on the day the first survey had been answered), participants were contacted again and sent the second survey (Time 2 = T2). Between 47 and 51 days (May 6 and 10)-, a third survey was sent to the participants (Time 3 = T3).

Procedures were conducted following the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (WMA, 2013). Adults voluntarily participated in the study after signing a digitally informed consent form. The potential risk of conducting online surveys in the quarantine context was taken into account; therefore, participants were given information about different psychological support services to which they could turn if necessary. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Research Board of the National University of Mar del Plata (Book 3. Nº 4/2020. F 120).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the entire sample and each level of the between-subjects variables (i.e., socio-demographic factors). A series of mixed repeated-measures ANOVAs were performed, allowing to evaluate (a) variations in depression, anxiety, negative and positive affect across the different waves of the study (Time: within-subject factor), (b) the effect of socio-demographic factors on the dependent variables (Group: between-subject factor), and (c) Group × Time interaction effects. Since the sphericity assumption was not met, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used in all of the models. In addition, to analyze the effect of Time on each dependent variable, a repeated-measures ANOVA was performed, with each assessment wave as the repeated measure (T1, T2, T3). Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni correction. Effect sizes were obtained for each model’s main effects and interaction effects (partial eta squared, ηp2), and pairwise comparisons (Cohen´s d; Cohen, 1988). All tests were two-sided, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 for Windows.

Results

Results of the Repeated Measures ANOVAs for anxiety, depression, positive affect, and negative affect are presented in Table 2. Means by each wave of assessment (T1, T2, and T3) and each socio-demographic variable are presented in Table 3. Effect sizes for mean differences are presented in Table 4.

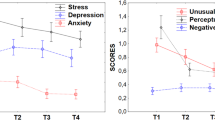

Anxiety

A significant main effect of Time on anxiety was observed. Pairwise comparisons show that anxiety decreases between T1 and T2, while it increases between T2 and T3. In addition, anxiety is higher at T3 than at T1 (in all cases, p < 0.001). This effect did not change due to differences in socio-demographic factors. Group × Time interaction effects were obtained for some of the socio-demographic variables. A series of contrasts were made to understand these effects, which are summarized below.

Perceived Economic Impact

The contrast for anxiety at T1 and T2 for the different levels of perceived economic impact is not significant, F (4, 3659) = 0.308, p = 0.873, while the contrast comparing T2 and T3 is significant, F (4, 3659) = 4.680, p = 0.001. Those who did not indicate any perceived economic impact showed a lower increase in their level of anxiety compared to those who reported different levels of perceived economic impact.

Older Adults in Care

The contrast for anxiety at T1 and T2 is not significant, F (1, 3831) = 0.149, p = 0.699, while the contrast comparing T2 and T3 is significant, F (1, 3831) = 4.637, p = 0.031. Those who do not have older adults in their care showed a greater increase in their level of anxiety from T2 to T3 compared to those who have adults in care.

Daily News Hours

The contrast for anxiety at T1 and T2 is significant, F (3, 3700) = 6.364, p < 0.001. Those who watch news 3–4 h or more than 4 h per day reduced their anxiety -between T1 and T2- to a greater extent than those watching less than 1 h per day of news. The contrast for T2 and T3 is not significant, F (3, 3700) = 1.872, p = 0.132.

Depression

A significant effect of Time on depression is observed. Pairwise comparisons show an increase in depression from T1 to T2 and from T2 to T3 (in all cases, p < 0.001). Group × Time interaction effects were obtained for some of the socio-demographic variables. A series of contrasts were made to understand these effects, which are summarized below.

Age Group

The contrast is not significant when comparing the level of depression at T1 and T2, F (3, 3829) = 2.569, p = 0.053, whereas the contrast is significant at T2 and T3, F (3, 3829) = 7.569, p < 0.001. Age affects the increase in depression from T2 to T3, resulting in a more pronounced increase the younger the age group.

Gender

The comparison of the level of depression at T1 and T2 is non-significant, F (1, 3803) = 0.002, p = 0.967, while the contrast for T2 and T3 is significant, F (1, 3803) = 6.189, p = 0.013. Women show a more pronounced increase in depression between T2 and T3 than men.

Perceived Economic Impact

The contrast is not significant when comparing depression at T1 and T2, F (4, 3659) = 1.837, p = 0.119. However, the contrast for T2 and T3 is significant, F (4, 3659) = 3.095, p = 0.015, indicating the increase in depression from T2 to T3 is less pronounced for those who did not perceive an impact on their income compared to those who did.

Number of Children

The contrast for depression at T1 and T2 is significant, F (4, 3828) = 2.416, p = 0.047, while the contrast for T2 and T3 is not, F (4, 3828) = 1.965, p = 0.097. The increase in depression from T1 to T2 is affected by the number of children: those with four or more children had a lesser increase in depression than those with fewer or no children.

Positive Affect

There is a significant effect of Time on positive affect. Pairwise comparisons show a decrease in positive affect between T1 and T2 (p = 0.003), and then an increase between T2 and T3 (p < 0.001). However, there were no differences between T1 and T3 (p > 0.05). When analyzing the effect of socio-demographic variables, the effect of Time remained significant in most cases. A Group effect was also observed on all variables except for older adults in care. A single interaction effect was observed, which is detailed next.

Gender

The contrast for positive affect at T1 and T2 is significant, F (1, 3803) = 10.464, p = 0.001, as well as the contrast for T2 and T3, F (1, 3803) = 5.610, p = 0.018, indicating that men show a more pronounced decrease in positive affect between T1 and T2, and a more pronounced increase between T2 and T3.

Negative Affect

There is a significant effect of Time on negative affect. Pairwise comparisons show that between T1 and T2, negative affect levels decrease, then increase between T2 and T3, and between T1 and T3 (in all cases, p < 0.001). This effect remains significant when considering differences based on socio-demographic variables. Group × Time interaction effects were observed in some socio-demographic variables. A series of contrasts were made to understand these effects, which are summarized below.

Age Group

The contrast for negative affect between T1 and T2 is non-significant, F (3, 3829) = 0.063, p = 0.979, while between T2 and T3 the contrast is significant, F (3, 3829) = 4.983, p = 0.002. The increase in negative affect from T2 to T3 is more pronounced for people between 18 and 60 years than for those over 60 years.

Perceived Economic Impact

The contrast for negative affect between T1 and T2 is not significant, F (4, 3659) = 1.109, p = 0.351, while the contrast for T2 and T3 is significant, F (4, 3659) = 3.821, p = 0.004. Those who did not perceive an economic impact show a less pronounced increase in negative affect between T2 and T3 than those that indicated perceiving an economic impact.

Number of Children

The comparison of negative affect at T1 and T2 is not significant, F (4, 3828) = 0.469, p = 0.759, while the comparison between T2 and T3 is significant, F (4, 3828) = 2.751, p = 0.027. Those with four or more children show a slight decrease in negative affect, while those with fewer or no children show an increase from T2 to T3.

Older Adults in Care

The contrast for negative affect at T1 and T2 is not significant, F (1, 3831) = 0.138, p = 0.710, while the contrast between T2 and T3 is significant, F (1, 3831) = 4.209, p = 0.040. The increase in negative affect between T2 and T3 is more pronounced among those without adults in their care.

Daily News

The contrast for negative affect at T1 and T2 is significant, F (3, 3700) = 4.130, p = 0.006, as well as the contrast for T2 and T3, F (3, 3700) = 4.270, p = 0.005. Those who watch less than 1 h per day of news showed a lower reduction in negative affect from T1 to T2 than those who watch more hours. The increase in negative affect from T2 to T3 was less pronounced for those who watch four or more hours of news per day than for those who watch fewer hours.

Effect of Gender and Age Group on Interaction Effects

We carried out a further set of mixed repeated measures ANOVAs to analyze the possible interaction effects by gender or age. Those models showed significant Group × Time interactions when conducted with Gender or Age group as an additional between-subjects factor. These analyses were performed for (a) Anxiety, with Perceived economic impact, Older adults in care, and Daily news hours; (b) Depression, with Age Group, Gender, perceived economic impact, and Number of children; (c) Positive Affect with Gender; (d) Negative Affect, with Age group, perceived economic impact, Number of children, Older adults in care and Daily news hours. Results indicate that the inclusion of Gender or Age group as an additional between-subjects factor does not result in significant Group × Gender × Time or Group × Age group × Time interaction effects; in all cases, F < 1.489, p > 0.09, ηp2 < 0.004. Thus, interaction effects were not modulated by gender or age.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and social isolation on the mental health of the Argentinian population. It was hypothesized that anxiety, depression, and negative affect would increase over time, while positive affect would decrease. Results on each dependent variable are discussed below.

Anxiety

Following previous studies, anxiety showed a slight decrease between T1 and T2 -after two weeks of lockdown- and then an increase between T2 and T3. The results coincide with those reported in a cross-sectional study also carried out in Argentina (López-Steinmetz et al., 2021), which indicates that anxiety levels tend to increase slightly between April and May.

The decrease in anxiety observed between T1 and T2 is similar to findings from previous studies (Benz et al., 2020; Fancourt & Steptoe, 2020). However, while anxiety decreases between T1 and T2, depression slightly increases. A series of authors have raised the possibility that this effect may be explained due to a state of learned helplessness which allow people to disengage their attention from threats and reduce feelings of fear and anxiety (Lifshin et al., 2020; López-Steinmetz et al., 2021). The learned helplessness could explain -among other factors- the increases in anxiety between T2 and T3. Also, changes in anxiety may be more transient and fluctuating in nature than depressive symptoms (Benz et al., 2020). As Lifshin et al. (2020) point out, more research is needed to understand the complex relationship between helplessness and anxiety. If the pandemic and the isolation measures continue, anxiety and depression may evidence a significant and sustained increase (Evanoff et al., 2020).

As in other studies (e.g., Bahrami & Yousefi, 2011; McLean et al., 2011), women reported more anxiety than men. This result is also congruent with recent studies showing a higher prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in women (Ausín et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020). Also, people who have three or more children showed less anxiety. This result may seem counterintuitive and previous findings are not conclusive. In this sense, Moscardino et al. (2021) showed that the increase in parental responsibilities stemming from activities such as home-schooling could be related to parental stress. However, on the other side, raising two or more children was related to less stress and more well-being than raising a single child both in pre-pandemic and pandemic situations (Brooks et al., 2020; Creese et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2008). Even though some authors suggest that parental experience helps to reduce stress (Berry & Jones, 1995; Brooks et al., 2020), further studies on the relationship between parental stress and parenting are still needed.

Regarding age, in line with different studies (e.g., Cao et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020), young adults (18 to 25 years old) showed more anxiety. According to the socio-emotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, 1993), young adults have a stronger need to socialize. Containment measures interfere with the satisfaction of this need, which could explain -in part- the higher levels of anxiety and depression in this age group (McMullen, 2021).

People with lower educational levels evidenced more anxiety. It seems a higher academic background could be a protective factor (Brooks et al., 2020; Moreira et al., 2020). On the contrary, Qiu et al. (2020) found that higher educational levels were associated with more symptoms. We needed more evidence to understand better the role of education in coping with anxiety in the context of prolonged isolation. Furthermore, the interaction effects on anxiety suggested that those who did not perceive economic impact showed a smaller increase in anxiety over time than those who report some degree of perceived economic impact. Some authors (Brooks et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020) found that financial loss is a risk factor for psychological distress during the pandemic.

In addition, people who do not have older adults in care showed a higher increase in anxiety between T2 and T3 than those who do. It is possible that caring for others may cause focusing attention on attitude management and withdrawing attention from other sources of stress. In this sense, taking care of someone is related to subjective indicators of quality of life such as something to live for, a sense of fulfillment, and self-esteem (Kuroiwa et al., 2016; Robak & Griffin, 2000).

Finally, those who watch fewer hours of news per day showed a greater decrease in anxiety between T1 and T2 than those who watch more hours. Contrarily, previous evidence suggests that sustained media exposure may increase anxiety and stress (Brooks et al., 2020; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020). Furthermore, the greater decrease in anxiety from T1 to T3 among those who watch more hours of news per day may be due to both an initially high level of anxiety during T1, as well as constant exposure leading to habituation (consequently, the same stimulus would not produce a response as intense as the initial one).

Depression

Similar to other studies conducted worldwide (e.g., Benz et al., 2020; Goularte et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2020) and in Argentina (López-Steinmetz et al., 2021) the levels of depression increased significantly over time. It should be noted that some studies found a reduction in pandemic impact over time (e.g., Wang et al., 2020), which was not observed at least until the third wave (T3) in the present study. In this regard, psychological symptomatology is expected to fluctuate along with the changes in containment measures and the increase in infections and deaths. As reported for anxiety, results indicated greater depressive symptomatology in people with lower education (secondary or less) and among those who watch more than two hours of news per day (Brooks et al., 2020).

Considering Time × Socio-demographic factors interactions, women appeared more vulnerable to depression than men over time (Ausín et al., 2020). Various factors may contribute to this (not only the prevalence of depression in women; see Salari et al., 2020), but women also showed a more pronounced increase in depression between T2 and T3. Women are the primary caregivers at home and also many women do not have a formal job, especially in middle-income countries like Argentina (Gausman & Langer, 2020). Finally, confinement increases the likelihood of gender-based violence (Mittal & Singh, 2020).

Further, depression levels were higher in young adults (18 to 25 years), as was consistently found by several studies (see Salari et al., 2020). Young adults also showed a higher increase in depression between T2 and T3. As noted, this group presents itself as particularly vulnerable to containment measures (McMullen, 2021). Similarly, Giuntella et al. (2020) found that university students at risk of clinical depression increased from 31 to 65% compared to pre-pandemic assessment. The authors explain this due to significant disruptions faced regarding their education and living situations and the possibility of facing lifelong economic impacts from the pandemic.

Individuals who reported that their income was unaffected showed a smaller increase in depression over time than those who reported some degree of income impact. In previous pandemics (see Brooks et al., 2020) and in the current one (e.g. Wilson et al., 2020), perceived changes in financial income have been associated with an increase in depressive symptoms.

Finally, those with a single child or no children experienced higher depression levels at the onset of the containment measures (i.e., from T1 to T2) than those with two or more children. Recent studies found that people with no children or only one child felt lonelier than those with two or more children (Creese et al., 2021).

Negative Affect

Negative affect showed a slight initial decrease (between T1 and T2) followed by an increase (between T2 and T3). The observed decrease between T1 and T2 may be due to negative emotions increasing during the first days of quarantine, which slowly decreased as people got used to the new situation. Higher levels of negative affect were observed in women, people with lower educational levels (secondary or more minor), and people who watched more hours of news. In this sense, some of the explanations about anxiety could also explain this pattern of results.

Consistent with studies showing a more significant impact on the social lives of the younger population (Chen et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020), when considering Time × Socio-demographic factors interactions, adults younger than 60 years showed a more pronounced increase in negative affect from T2 to T3 than those older than 60 years. For example, young and middle-aged adults faced more interpersonal conflicts, study issues, and family-related daily stress (Uchino, 2006). Furthermore, those who perceived some degree of economic impact showed a higher increase in negative affect between T2 and T3 than those who did not report affected income. Understandably, a differential increase in negative affect concerning perceived economic impact did not occur at the beginning of the pandemic because the duration of containment measures was unknown, and economic changes were not yet perceived. However, the prolonged pandemic may have generated more negative emotions in those who perceived a decline in income.

When considering the number of children, negative affect slightly decreased from T2 to T3 for those with four or more children, whereas it increased for those with fewer or no children. As mentioned, people with more children tend to feel less lonely and experience fewer negative feelings (Creese et al., 2021). Also, negative affect showed a more pronounced decrease between T2 and T3 for those with elderly in their care. Previous research indicated that caregiving generates a sense of accomplishment and a feeling of having something to live for (Kuroiwa et al., 2016). Finally, those who watch more hours of news per day showed a greater decrease in negative affect between T1 and T2, probably due to habituation resulting from constant exposure to the same stimuli over time.

Positive Affect

Positive affect shows a slight decrease from T1 to T2, followed by an increase from T2 to T3, which can be understood as an adaptation to the situation. Higher levels of positive affect were observed in people who quarantined, people with higher levels of education, and people who watched fewer hours of news per day. There was a single time × Socio-demographic factors interaction: men reported a more considerable decrease in positive affect from T1 to T2 than women. This could be explained by changes in their daily routines, by an increase in the number of hours at home, and by sharing parenting and caregiving roles to which they might not be used to (Cerrato & Cifre, 2018). Then from T2 to T3, men showed a higher increase in positive affect than women; this could be due to men typically expressing emotions associated with power and status and scoring higher in items such as those included in the PANAS (Brody, 1997), so they will likely return after a period of adaptation to more basal levels in these emotions.

Limitations

Concerning the limitations of this study, future longitudinal studies may implement procedures to avoid biases in sample composition and measures to avoid attrition. Sample biases have been introduced by using online surveys, as only a part of the Argentinian population is accessible through them, especially people with high living standards or younger people. Another source of bias is the attrition in the subsequent survey waves. Those that did not respond to all stages of the study had worse scores in depression, anxiety, and negative affect indicators; this is some form of "survival of the fittest", and as such, we can conclude that this study sheds a favorable light over the actual distribution of psychological distress in the Argentinian population. In this sense, future longitudinal studies should consider these issues and be cautious in the generalization of the results obtained in this study.

Conclusions

While there are differences in the trajectory of the affective variables during the pandemic, there is a trend towards a moderate increase over time in anxiety, depression, and negative affect, and a decrease in positive affect. Taken together, this indicates the emotional impact of the pandemic. Furthermore, it does not seem to affect everyone equally; some groups like young adults aged 18 to 25, women, those who perceive a significant impact on their income, those with fewer or no children, those with secondary or lower education, those with no older adult dependents, and those who watch more hours of news per day since the start of the pandemic are more vulnerable than others. This vulnerability is relevant because policymakers and service providers need reliable information about changes in mental health associated with the pandemic. Decisions are underpinned by knowledge of changes in the population's mental health and who is most vulnerable to symptoms of mental distress (Pierce et al., 2020).

Beyond its limitations, this study could contribute to the knowledge of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health by exploring fluctuations experienced by the population from the onset of isolation measures. It provides evidence on which variables were most affected over time in the population and which groups were vulnerable. Policymakers and service providers may find in these results possible inputs to base their decisions and justify their interventions toward those most in need. Also, these results indicate the need for more financing for mental health and initiatives to encourage women with lived experiences to participate in the planning and execution of the suggested actions. The U.S. Surgeon General's Advisory (2021) shares some guidelines that we have adapted as suggestions: address the economic and social barriers that contribute to poor mental health for women, ensure most people have comprehensive and affordable coverage for mental health care, expand the use of telehealth for mental health challenges and expand and support the mental health workforce. In addition, some authors have pointed out the need to develop rapid response strategies to mental health crises as a consequence of the pandemic, adapting services to ensure continuity of care and access to care for the new demand that has arisen (Irarrazaval et al., 2021). Government preparedness for future pandemics and support for mental health, individual finance, and community organizations should be policy priorities in the post‐COVID‐19 recovery phase (Hammarberg et al., 2021).

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results of this study will be made available upon reasonable request.

References

Ausín, B., González-Sanguino, C., Castellanos, M. Á., & Muñoz, M. (2020). Gender-related differences in the psychological impact of confinement as a consequence of COVID-19 in Spain. Journal of Gender Studies, 30(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2020.1799768

Bahrami, F., & Yousefi, N. (2011). Females are more anxious than males: A metacognitive perspective. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 5(2), 83–90.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck depression Inventory-II. The Psychological Corporation.

Benz, A., Meier, M., Bentele, U. U., Dimitroff, S. J., Denk, B., Pruessner, J., & Unternaehrer, E. (2020). Early life adversity, dispositional mindfulness, and longitudinal stress experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5kt6z

Berry, J. O., & Jones, W. H. (1995). The parental stress scale: Initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(3), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0265407595123009

Brenlla, M. E., & Rodríguez, C. M. (2006). Adaptación argentina del Inventario de Depresión de Beck (BDI-II) [Argentine adaptation of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)]. In A. T. Beck, R. A. Steer & G. K. Brown (Ed.), BDI-II. Inventario de Depresión de Beck. Segunda Edición. Manual [BDI-II. Beck Depression Inventory. Second Edition. Manual]. Paidós.

Breslau, J., Finucane, M. L., Locker, A. R., Baird, M. D., Roth, E. A., & Collins, R. L. (2021). A longitudinal study of psychological distress in the United States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preventive Medicine, 143, 106362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106362

Brody, L. R. (1997). Gender and emotion: Beyond stereotypes. Journal of Social Issues, 53(2), 369–393.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395, 912–920.

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934.

Carstensen, L. L. (1993). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In J. E. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation: 1992, developmental perspectives on motivation (Vol. 40, pp. 209–254). University of Nebraska Press.

Cerrato, J., & Cifre, E. (2018). Gender inequality in household chores and work-family conflict. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01330

Chen, B., Sun, J., & Feng, Y. (2020). How have COVID-19 isolation policies affected young people’s mental health? - Evidence from Chinese college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01529

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates.

Creese, B., Khan, Z., Henley, W., O’Dwyer, S., Corbett, A., Vasconcelos Da Silva, M., & Ballard, C. (2021). Loneliness, physical activity, and mental health during COVID-19: A longitudinal analysis of depression and anxiety in adults over the age of 50 between 2015 and 2020. International Psychogeriatrics, 33(5), 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220004135

Daks, J. S., Peltz, J. S., & Rogge, R. D. (2020). Psychological flexibility and inflexibility as sources of resiliency and risk during a pandemic: Modeling the cascade of COVID-19 stress on family systems with a contextual behavioral science lens. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.08.003

Daly, M., Sutin, A. R., & Robinson, E. (2020). Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720004432

de Quervain, D., Aerni, A., Amini, E., Bentz, D., Coynel, D., Gerhards, C., Fehlmann, B., Freytag, V., Papassotiropoulos, A., Schicktanz, N., Schlitt, T., Zimmer, A., Zuber, P. (2020). The Swiss Corona Stress Study. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/jqw6a

Dunford, D., Dale, B., Stylianou, N., Lowther, E., Ahmed, M., & de la Torre Arenas, I. (2020). Coronavirus: The world in lockdown in maps and charts. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52103747

Evanoff, B. A., Strickland, J. R., Dale, A. M., Hayibor, L., Page, E., Duncan, J. G., Kannampallil, T., & Gray, D. L. (2020). Work-related and personal factors associated with mental well-being during the COVID-19 response: Survey of health care and other workers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e21366. https://doi.org/10.2196/21366

Fancourt, D., & Steptoe, A. (2020). COVID-19 social study. 3(April). https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/project/covid-19-social-study

Gausman, J., & Langer, A. (2020). Sex and gender disparities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Women’s Health, 29(4), 465–466. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8472

Giuntella, O., Hyde, K., Saccardo, S., & Sadoff, S. (2020). Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. IZA Institute for Labor Economics. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3666985

Goularte, J. F., Serafim, S. D., Colombo, R., Hogg, B., Caldieraro, M. A., & Rosa, A. R. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health in Brazil: Psychiatric symptoms in the general population. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 132, 32–37.

Goyal, K., Chauhan, P., Chhikara, K., Gupta, P., & Singh, M. P. (2020). Fear of COVID 2019: First suicidal case in India! Asian journal of Psychiatry, 49, 101989.

Hammarberg, K., Tran, T., Kirkman, M., Rowe, H., & Fisher, J. (2021). Preferred policy options to assist post-COVID-19 mental health recovery: A population study. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 80(3), 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12507

Hawryluck, L., Gold, W. L., Robinson, S., Pogorski, S., Galea, S., & Styra, R. (2004). SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(7), 1206–1212.

Irarrazaval, M., Norambuena, P., Montenegro, C., Toro-Devia, O., Vargas, B., & Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2021). Public policy responses to address the mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Chile. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 590335. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.590335

Kelvin, D. J., & Rubino, S. (2020). Fear of the novel coronavirus. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 14(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.12496

Kuroiwa, S., Kita, K., Watanabe, F., Miura, T., Kuroiwa, M., Koura, T., Yoshida, K., Minami, S., & Yamashiro, S. (2016). Do care activities by elderly people lead to an increased sense of purpose in life? An Official Journal of the Japan Primary Care Association, 39(2), 116–121.

Leibovich de Figueroa, N. B. (1991). Ansiedad: Algunas concepciones teóricas y su evaluación [Anxiety: Some theoretical conceptions and its evaluation.]. In M. M. Casullo, N. B. Leibovich de Figueroa, & M. Aszkenazi (Eds.), Teoría y técnicas de evaluación psicológica [Theory and techniques of psychological assessment] (pp. 123–155). Psicoteca.

Lifshin, U., Mikulincer, M., & Kretchner, M. (2020). Motivated helplessness in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between perceived ability to avoid the virus and anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 39(6), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2020.39.6.479

Lima, C. K. T., de Medeiros Carvalho, P. M., Lima, I. D. A. A. S., de Oliveira Nunes, J. V. A., Saraiva, J. S., de Souza, R. I., & Neto, M. L. R. (2020). The emotional impact of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new Coronavirus disease). Psychiatry Research, 287, 112915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112915

Liu, X., Kakade, M., Fuller, C. J., Fan, B., Fang, Y., Kong, J., & Wu, P. (2012). Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53, 15–23.

López-Gómez, I., Hervás, G., & Vázquez, C. (2015). Adaptación de las “Escalas de afecto positivo y negativo” (PANAS) en una muestra general española. Psicología Conductual, 23, 529–548.

López-Steinmetz, L. C., Leyes, C. A., Florio, M. A. D., Fong, S. B., Steinmetz, R. L., & Godoy, J. C. (2021). Mental health impacts in Argentinean college students during COVID-19 quarantine. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 557880. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.557880

McLean, C. P., Asnaani, A., Litz, B. T., & Hofmann, S. G. (2011). Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(8), 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006

McMullen, S. (2021). Why is the pandemic so hard on young people? Greater good magazine. Science-based insights for a meaningful life. Education. Berkeley. University of California. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/why_is_the_pandemic_so_hard_on_young_people

Mittal, S., & Singh, T. (2020). Gender-based violence during COVID-19 pandemic: a mini-review. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 1, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2020.00004

Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, A. (2020). Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076

Moreira, P. S., Ferreira, S., Couto, B., Machado-Sousa, M., Fernandez, M., Raposo-Lima, C., Souza, N., Pico-Perez, M., & Morgado, P. (2020). Protective elements of mental health status during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Portuguese population. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.28.20080671

Moriondo, M., De Palma, P., Medrano, L. A., & Murillo, P. (2012). Adaptación de la Escala de Afectividad Positiva y Negativa (PANAS) a la población de adultos de la ciudad de Córdoba: Análisis psicométricos preliminares. Universitas Psychologica, 11(1), 187–196.

Moscardino, U., Dicataldo, R., Roch, M., Carbone, M., & Mammarella, I. C. (2021). Parental stress during COVID-19: A brief report on the role of distance education and family resources in an Italian sample. Current Psychology, 40, 5749–5752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01454-8

Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E., Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B., & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry, 33(2), e100213. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213

Robak, R. W., & Griffin, P. W. (2000). Purpose in life: What is its relationship to happiness, depression, and grieving? North American Journal of Psychology, 2(1), 113–119. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-16046-011

Rossi, R., Socci, V., Talevi, D., Mensi, S., Niolu, C., Pacitti, F., Di Marco, A., Rossi, A., Siracusano, A., & Di Lorenzo, G. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 790. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., Rasoulpoor, S., & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

Serafini, G., Parmigiani, B., Amerio, A., Aguglia, A., Sher, L., & Amore, M. (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(8), 531–537. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201

Shanahan L, Steinhoff A, Bechtiger L, Murray AL, Nivette A, Hepp U, Ribeaud D, Eisner M (2020). Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000241X

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1970). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R. E., & Cubero, N. S. (1999). STAI: Cuestionario de Ansiedad Estado-Rasgo. TEA.

Taylor, M. R., Agho, K. E., Stevens, G. J., & Raphael, B. (2008). Factors influencing psychological distress during a disease epidemic: data from Australia’s first outbreak of equine influenza. BMC Public Health, 8, 347. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-347

U.S. Surgeon General. (2021). Protecting youth mental health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf

Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377–387.

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., McIntyre, R. S., Choo, F. N., Tran, B., Ho, R., Sharma, V. K., & Ho, C. (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Wilson, J. M., Lee, J., Fitzgerald, H. N., Oosterhoff, B., Sevi, B., & Shook, N. J. (2020). Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(9), 686–691. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962

World Health Organization. (2020). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.who.int/docs/defaultsource/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf

World Medical Association. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. https://www.wma.net/policiespost/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-researchinvolving-human-subjects/

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia Tecnología e Innovación (Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation) of Argentina. Programa de articulación y fortalecimiento federal de las capacidades en ciencia y tecnología COVID-19; Grant code IF-2020–37418385-APN-SSFCTEI#MCT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Research Board of the National University of Mar del Plata (Book 3. Nº 4/2020. F 120). Procedures were conducted following the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Canet-Juric, L., Vernucci, S., Andrés, M.L. et al. As Time goes by: A Longitudinal Study on the Mental Health of Argentinians during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Trends in Psychol. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-023-00285-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-023-00285-9