Abstract

Background

Several studies have investigated the relationship between dietary patterns and the risk of bladder cancer (BC) in different regions including Europe, the United States, and Asia, with no conclusive evidence. A meta-analysis was undertaken to integrate the most recent information on the relationship between a data-driven Western diet (WD), the Mediterranean diet (MD), and dietary-inflammatory-index (DII) and the risk of BC.

Method

We looked for published research into the relationship between dietary patterns and the incidence of BC in the PubMed/Medline, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Scopus databases up until February 2021. Using a multivariate random-effects model, we compared the highest and lowest categories of WD, MD and DII patterns and provided the relative risk (RR) or odds ratios (OR) and 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs) for the relevant relationships.

Results

The analysis comprised 12 papers that were found to be suitable after scanning the databases. Both case–control (OR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.52, 0.94; I2 = 49.9%, n = 2) and cohort studies (RR 0.93, 95% CI: 0.88, 0.97; I2 = 63%, n = 4) found a substantial inverse association between MD and BC. In addition, although cohort studies (RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.37, 1.70; I2 = 0%, n = 2) showed a direct association between WD and BC, case–control studies (OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.81, 1.88; I2 = 68.5%, n = 2) did not. In cohort studies, we found no significant association between DII and BC (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.93, 1.12; I2 = 38.5%, n = 2). In case–control studies, however, a strong direct association between DII and BC was discovered (RR 2.04, 95% CI 1.23, 2.85; I2 = 0%, n = 2).

Conclusion

The current meta-analysis showed that MD and WD have protective and detrimental effects on BC risk, respectively. No significant association between DII and the risk of BC was observed. More research is still needed to confirm the findings. Additional study is warranted to better understand the etiological mechanisms underlying how different dietary patterns affect BC.

Trial registration

Protocol registration number: CRD42020155353.

Database for protocol registration: The international prospective register of systematic reviews database (PROSPERO).

Data of registration: August 2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Being among the top ten most common types of cancer in the world, cancer of the bladder (BC) causes approximately 550,000 new cases annually [1]. With regard to the geographical distribution the risk of bladder cancer is the highest in Southern and Eastern Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and North America[2]. About 75% of cases of BC are non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), a type that frequently recur and requires intensive treatment and follow-up measures posing a large burden on any national health care budgets [3]. Epidemiological studies introduced several factors that potentially influence the risk of bladder cancer. These factors include, sex, age, occupation, and smoking [3, 4]. Urinary tract infections and exposures to arsenic or aromatic amines like heterocyclic amines (HCAs), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are also among the potential risk factors for BC [5]. Furthermore, more information is becoming available on the possible role of food in the development of BC [5]. However, according to the latest report from World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), the evidence from epidemiologic studies on the above association is scarce and largely inconsistent [6].

Epidemiological studies suggested that several environmental and lifestyle related factors, e.g., pollutions and diet, might also play important roles in the risk of BC [7, 8]. In terms of diet, epidemiological studies have examined at the associations between certain foods and the risk of BC, with some intriguing results. As such, animal fat, a high red meat intake, and refined carbohydrate, that are the major component of the Western diet (WD), are associated to an elevated risk of BC [9,10,11]. In contrast, the Mediterranean diet's key components, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and dietary fiber, have been associated to a lower incidence of BC [12,13,14,15,16,17]. The MD contains sufficient of fiber (found in fruits and vegetables), legumes and grains, fish, moderate wine intake, low-to-moderate milk and dairy products consumption, and minimal meat and meat products consumption [16, 18]. WD, on the other hand, is a dietary pattern that includes a lot of high-fat animal meat, processed products, red meat, and high-sugar foods [19,20,21]. Based on the existing evidence, MD is a significant protective factor for several non-communicable diseases [22,23,24].

Foods contain many interacting nutrients affecting body’s function and well-being. Although several studies associated particular food items are with BC, the evidence is inconclusive [25, 26]. This is because, individuals do consume food items together and it is therefore rather than focusing at individual nutrients when analyzing food, it's critical to apply a holistic approach. Among the several methods in nutritional epidemiology, dietary pattern analysis is now often regarded as a more effective method for determining the overall impact of food consumption on health. Given the fact that the relationship between dietary pattern and BC has attained increasing attention, the evidence remains inconclusive. For example, a few studies reported hazardous effects of WD on the risk of BC [9,10,11], whereas others found an inverse association between WD (or healthy diets) and BC [12,13,14,15,16,17]. To sum up, although the association of BC in association to dietary pattern, has been investigated by several researchers in Europe, United States, and Asia, no conclusive evidence over the subject has been made. We performed a meta-analysis of cohort and case–control studies to integrate the most recent evidence on the relationship between WD, MD, and DII and the risk of BC among those who were suffering from the BC.

Methods

This study was carried out in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) standard recommendations [27].

Protocol and registration

The aim of this study was to see if there was an association between dietary habits and the risk of developing BC. In August 2020, the study protocol was registered with the CRD42020155353 registration number in the international prospective register of systematic reviews database (PROSPERO) (Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=155353).

Search strategy and selection criteria

Without restrictions, we searched PubMed/Medline, Web of Science (ISI), Cochrane library, Clinicaltrials.gov, and SCOPUS databases for papers that indicated a relation between dietary patterns and the risk of BC up to February 2021. The following search keywords or phrases were used to find relevant articles: ("neoplasm" OR "cancer" OR "carcinoma") AND ("bladder" OR "urinary bladder") AND ("dietary pattern" OR "eating pattern" OR "food pattern" OR "dietary habit" OR "diet" OR "dietary"). Additionally, the reference lists of the included papers and recent major reviews were carefully evaluated to find other relevant publications in order to prevent missing any related article. Review studies, and if the retrieved publications didn’t fulfilled the following inclusion criteria, they were excluded in our study: studies with a case–control or cohort design, reported the associations between dietary patterns and BC, included newly diagnosed cases of BC, diagnosed all cases using pathological biopsies or other standard methods, and provided relative risks (RRs), hazards ratios (HRs), or odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95 percent confidence intervals for the dietary patterns. We included the most often identified dietary patterns across studies to reduce the possibility of misclassifications, and we made sure that the selected dietary patterns were specified consistently in terms of factor loadings of the most frequently consumed foods as much as feasible. The categorization of Western, Mediterranean and DII dietary patterns was based on selected peer-reviewed publications. When several publications from the same data were found, the publication with the most participants/person-years was chosen. The selected articles and reading the titles and abstracts of the searched papers independently were examined by two independent reviewers (NA and DB). If both reviewers agreed that a publication did not fulfill the above-mentioned inclusion criteria, it was excluded. Inconsistencies (if any) were to be solved by a consultation with a third author (MD).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Using a standardized data collection form, two reviewers independently extracted the required information. From each study, we gathered the following data: first author's last name; year of publication; study location; study design; sample size; duration of follow-up; method of analysis; diagnostic criteria; gender; average age of participants; dietary valuation methods; dietary patterns; RRs, HRs, or ORs and the corresponding 95% CIs for the highest vs. the lowest categories; of dietary patterns from the final adjusted models and potential confounders adjusted in the multivariate analysis. The authors were contacted by email at least twice, one week apart, when the full text of a paper was unavailable or if any essential information was missing in the provided data. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to measure quality assessment of the included studies [28]. Concisely, we used a nine-score tool based on the NOS to assess the quality of the studies characterized by three broad criteria: [1] appropriate study population selection, [2] study group comparability, and [3] ascertainment of the exposure (for cohort studies) or outcome (for case control studies) of interest. Each study's quality was independently assessed by two reviewers (NA and DB). Disagreements were once again resolved by discussion among the reviewers. Studies having a score of 7 or above, with 9 being the maximum, were deemed to be of high quality.

Statistical analyses

The observed relationship between dietary patterns and the risk of BC was measured using RRs as the common scale. As RR estimators, HRs, ORs, and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were also utilized [29]. We conducted random-effects meta-analysis to obtain the pooled RR and its 95% confidence intervals.

Because of the potential heterogeneity in clinical and methodological characteristics within and between studies, the random-effects analysis was used [30].

To assess heterogeneity across studies, we utilized Q statistics with a significance level of P < 0.10. We also used the I2 statistic to indicate the variance between studies that may be attributed to heterogeneity rather than chance. Moderate heterogeneity was defined as an I2 value larger than 50% [31].

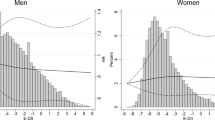

To measure the impact of individual or a group of studies on the results e conducted a sensitivity analysis. We tested for publication bias by visual inspection of Begg’s funnel plots presenting log RRs against their standard errors (SEs) [32, 33]. STATA version 15.0 was used for all analyses (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas). Except otherwise specified, statistical significance was defined as a P-value of less than 0.05.

Results

Study characteristics

Following the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) of the study selection process, we found a total of 2554 articles from the searched databases. Some were excluded because of duplication and being irrelevant articles. Eventually, seven cohort studies [10, 11, 14,15,16,17, 34], and five case control studies [9, 12, 13, 35, 36] were included in the present mete-analysis. Included cohort studies consisted of 12,679 cases and 1,952,859 non-cases. In addition, the case–control studies included 1891 cases and 2326 controls. The study selection procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The details of the included studies are shown in Table 1. Of the Included articles that were published between 2008 and 2020, six studies assessed the effect of MD on BC risk [12,13,14,15,16,17], three articles investigated the associations between WD and BC [9,10,11], and three studied on DII and BC [34,35,36]. Two of them were conducted in Italy [12, 35] and others were conducted in Netherlands [15], two from EPIC study [14, 16], Belgium [13], Australia [17], Uruguay[9], Iran [36], united states [11, 34], and one from Australia, European countries and united states [10]. Dietary intake was assessed using food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) in almost all the included studies. Adjustment-variables were mostly age, sex, smoking, total energy intake, body mass index, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and family history of BC.

Association between a Western dietary patterns and risk of BC

The combined RR for the highest vs. the lowest category of a WD and risk of BC was 1.52 (95% CI 1.36, 1.67), with no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 19.5%, p = 0.29) (Fig. 2). A similar pattern of association was observed in cohort studies (RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.37, 1.70), again with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, p = 0.82). In contrast, we found no significant association between a WD and risk of BC in case–control studies (OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.81, 1.88; I2 = 68.5%, p = 0.07).

Association between Mediterranean diet and risk of BC

According to Fig. 3, six studies (4 cohorts; 2 case–control) examined the effects of a MD and risk of BC, and their results were conflicting. As shown in Fig. 3, the overall RR of the association between risk of BC for the highest vs. the lowest category of MD was protective (RR 0.92, 95% CI: 0.87, 0.96), with a significant heterogeneity (I2 = 62.5%, p = 0.02). We found the same pattern with pooled estimate, in both cohorts (RR 0.93, 95% CI: 0.88, 0.97; I2 = 63%, p = 0.04) and case control studies (OR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.52, 0.94; I2 = 49.9%, p = 0.15).

Association between DII and risk of BC

The combined RR for the highest vs. the lowest category of a DII and risk of BC was 1.04 (95% CI 0.94, 1.13), with a significant heterogeneity (I2 = 61.4%, p = 0.05) (Fig. 4). We found a similar association in cohort studies (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.93, 1.12), with no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 38.5%, p = 0.20). In case–control studies, however, a strong direct association was identified between a DII and the risk of BC (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.23, 2.85; I2 = 0%, p = 0.67).

Quality assessment and sensitivity analysis

Table 2 shows the methodological quality of the selected studies according to the NOS. The NOS scores for the included studies ranged from 6 to 8, with 11 high [9, 10, 12,13,14,15,16,17, 34,35,36] and one medium-quality [11]. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to check if the results would change when each individual study was removed at a time. Except for studies on DII and risk of BC, the results were fairly robust after removing studies from the meta-analyses. Results of publication bias were not provided according to the reviewers suggestions.

Discussion

In the meta-analysis, we reviewed the investigated associations between adherence to major dietary patterns and risk of BC. We observed a direct association between WD and risk of BC, and an inverse association between MD and risk of developing BC. However, there was no association between DII and BC risk.

Several systematic review and meta-analyses have investigated the association between dietary patterns and the risk of cancer of other organs, WD was associated with increased risk of colorectal [37, 38], stomach [39], and prostate cancers [40]. Similar to our results, a meta-analysis with 12 observational studies reported that WD is related to an increased risk of prostate cancer but no association between healthy pattern and prostate cancer risk [40]. However, to date no meta-analysis is available on the association between dietary patterns and BC. The results published from studies that have examined the relationship between WD and risk of BC are in accordance with our findings [9,10,11]. For example, the results of a recently published pooled analysis on 13 cohorts suggested that adherence to a WD pattern is associated with an increased risk of BC [10]. Also, Westhoff et. al. found that greater adherence to a WD was associated with a higher risk of BC recurrence [11]. This finding supports the hypothesis that WD plays a role in the etiology and prognosis of BC. According to the results, although a strong association was observed between higher adherence to a WD and BC in cohort studies (RR 1.55, 95%CI: 1.37 to 1.70), we found no significant association between WD and risk of BC in case–control studies (RR 1.30, 95%CI: 0.81 to 1.88). This might be due to recall bias in these studies and even small sample size of the included case control studies.

Epidemiological studies have concentrated on some key elements of WD and reported a positive associations between red and processed meat, refined grain and saturated fats and risk of BC [41]. Red and processed meat is one of the important key elements of this dietary pattern and it is positively associated with the risk of BC [42]. Potentially hazardous materials present in the WD, such as N-nitroso-compounds, heterocyclic aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in red meat, are excreted in the urine. As a result, they come into direct contact with the inner lining of the bladder wall, potentially causing cancer in urothelial cells [43]. Moreover, it is suggested that red and processed meats contain saturated fat and heme iron, potential inducers of oxidative stress and DNA damage [44]. Also, more mutagenic substitutes during the cooking procedure of these nutrients takes place. As mentioned by Matteo et. al., cooking meat or fats, main components of WD, at higher temperatures (roasting) or for prolonged times (e.g., stewing) were associated with an increased BC risk [45]. According to the previous studies, components produced during food processing, particularly when meat is cooked at higher temperatures or for longer periods of time, can damage DNA and increase the risk of cancer [45,46,47]. However, the lack of information on cooking and preparing food in the included studies prevented us to conduct a subgroup analysis according to the cooking methods.

Regarding adherence to MD and cancer risk, results of a systematic review reported that MD was inversely associated with cancer mortality and risk of colorectal, breast, gastric, liver, head and neck, gallbladder, and biliary tract cancers [48]. However, a meta-analysis of 10 epidemiological studies provided evidence that MD is not related with prostate cancer risk [49]. In our meta-analysis the association between MD and risk of BC was reported by 6 studies [12,13,14,15,16,17]. We found a stronger association between MD and BC in cohort studies rather than case–control studies. A pooled analysis of 13 cohort studies showed that adherence to the MD was associated with a reduced risk of developing BC (HR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.77, 0.93), suggesting a positive effect of a MD on BC risk [16]. In addition, Dugué et al. discovered a moderate inverse relationship between MD adherence and urothelial cell cancer [17]. Also, Buckland et al. found an inverse associations between adherence to the MD and occurrence of overall, aggressive or non-aggressive, BC for both gender [14]. It is suggested that, among key elements of this diet, some of them had beneficial effects on the prevention of BC. For example, it has been shown that the consumption of vegetables and fruits, as the main components of the WD, are inversely associated with the risk of BC [50, 51]. It is suggested that, polyphenols, carotenoids, and vitamins C and E are abundant in both vegetables and fruits, and they serve as antioxidants, preventing DNA damage by neutralizing reactive oxygen species [52]. Olive oil is another significant component of the MD that has been examined as a single dietary item in relation to bladder cancer. Brinkman et al. showed that a higher consumption of olive oil was inversely related to the risk of BC [13].

Regarding DII, A meta-analysis found that higher pro-inflammatory diets are linked to an increased risk of prostate, kidney, and bladder cancer [53], results that are different with our finding. In this study, we investigated 2 case–control and 2 cohort studies [17, 34,35,36] on the association of DII and BC. Our pooled estimates show that DII was not significantly associated with the BC risk. Null association between a DII and BC in cohort studies suggests that the significant association found in case–control studies may be due to recall bias rather than a real association. The discrepancies between the individual studies could be attributed to the small sample sizes, study design or population substructure. Chronic inflammation causes oxidative and nitrative DNA damage in stem cells, which might be one of the processes behind the observed positive relationship between DII and BC [54].

There are probably differences in the definitions of diets in different studies, so we used the most common definition. However, there are some limitations to this meta-analysis, as such, the results are combined from studies conducted with different methods in different populations, resulting in heterogeneity. Among several potential explanations, recall bias occurs a lot in case control studies rather than cohort studies. Moreover, a possible misclassification within the considered dietary patterns may existed. We cannot generalize our results to the whole world because the most studies that we found were from European and developed countries. As a result, more studies are needed, especially in Asian and African countries, to support these findings.

Conclusions

Our results specified a direct association between WD and risk of BC, and an inverse association between MD and risk of developing BC. Also, there was no association between DII and BC risk. According to our findings dietary patterns might play an important role in BC prevention and guidelines might provide more attention to recommend consuming MD components and reducing WD components. However, further researches are needed to confirm our findings and to study the possible mechanisms for the WD effects on carcinogenesis of BC and MD and their effects on BC prevention.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Bladder cancer

- DII:

-

Dietary-inflammatory-index

- WD:

-

Western diet

- MD:

-

Mediterranean diet

- FFQ:

-

Food-frequency questionnaire

- RRs:

-

Relative risks

- HRs:

-

Hazard ratios

- ORs:

-

Odds ratios

- Cis:

-

Confidence intervals

- SEs:

-

Standard errors

- NOS:

-

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

References

Richters A, Kiemeney AKKH, L,. The global burden of urinary bladder cancer: an update. World J Urol. 2020;38:1895–904.

Parkin DM. The global burden of urinary bladder cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 2008;42:12–20.

Mossanen M, Gore JL. The burden of bladder cancer care: direct and indirect costs. Curr Opin Urol. 2014;24:487–91.

Al-Zalabani AH, Stewart KF, Wesselius A, et al. Modifiable risk factors for the prevention of bladder cancer: a systematic review of meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:811–51.

Janković S, Radosavljević V. Risk factors for bladder cancer. Tumori Journal. 2007;93:4–12.

Marmot M, Atinmo T, Byers T et al. (2007) Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective.

Zeegers MP, Volovics A, Dorant E, et al. Alcohol consumption and bladder cancer risk: results from The Netherlands Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:38–41.

Volanis D, Kadiyska T, Galanis A, et al. Environmental factors and genetic susceptibility promote urinary bladder cancer. Toxicol Lett. 2010;193:131–7.

De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Ronco AL, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of bladder cancer: a factor analysis in Uruguay. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:1243.

Dianatinasab M, Wesselius A, Salehi‐Abargouei A, et al. Adherence to a Western dietary pattern and risk of bladder cancer: A pooled analysis of 13 cohort studies of the Bladder Cancer Epidemiology and Nutritional Determinants international study. International Journal of Cancer. 2020;147(12):3394-403.

Westhoff E, Wu X, Kiemeney LA, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of recurrence and progression in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;142:1797–804.

Bravi F, Spei M-E, Polesel J, et al. Mediterranean diet and bladder cancer risk in Italy. Nutrients. 2018;10:1061.

Brinkman MT, Buntinx F, Kellen E, et al. Consumption of animal products, olive oil and dietary fat and results from the Belgian case-control study on bladder cancer risk. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990). 2011;47:436–42.

Buckland G, Ros M, Roswall N, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of bladder cancer in the EPIC cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2504–11.

Schulpen M, van den Brandt PA. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risks of prostate and bladder cancer in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2019;28:1480–8.

Witlox WJ, van Osch FH, Brinkman M, et al. An inverse association between the Mediterranean diet and bladder cancer risk: a pooled analysis of 13 cohort studies. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59:287–96.

Dugué PA, Hodge AM, Brinkman MT, et al. Association between selected dietary scores and the risk of urothelial cell carcinoma: A prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:1251–60.

Antonopoulou M, Mantzorou M, Serdari A, et al. Evaluating Mediterranean diet adherence in university student populations: Does this dietary pattern affect students’ academic performance and mental health? Int J Health Plann Manage. 2020;35:5–21.

Christ A, Latz LM, E,. Western Diet and the Immune System: An Inflammatory Connection. Immunity. 2019;51:794–811.

Jalilpiran Y, Dianatinasab M, Zeighami S, et al. Western Dietary Pattern, But not Mediterranean Dietary Pattern, Increases the Risk of Prostate Cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2018;70:851–9.

Stoll BA. Western diet, early puberty, and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;49:187–93.

Bo S, Ponzo V, Goitre I, et al. Predictive role of the Mediterranean diet on mortality in individuals at low cardiovascular risk: a 12-year follow-up population-based cohort study. J Transl Med. 2016;14:91.

Mourouti N, Panagiotakos DB. The beneficial effect of a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra virgin olive oil in the primary prevention of breast cancer among women at high cardiovascular risk in the PREDIMED Trial. Evid Based Nurs. 2016;19:71–71.

Dianatinasab M, Rezaian M, HaghighatNezad E, et al. Dietary Patterns and Risk of Invasive Ductal and Lobular Breast Carcinomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;20:e516–28.

Catsburg CE, Gago-Dominguez M, Yuan JM, et al. Dietary sources of N-nitroso compounds and bladder cancer risk: findings from the Los Angeles bladder cancer study. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:125–35.

Ferrucci LM, Sinha R, Ward MH, et al. Meat and components of meat and the risk of bladder cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer. 2010;116:4345–53.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100.

Wells G (2004) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analysis. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm.

Xiao Y, Xia J, Li L, et al. Associations between dietary patterns and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21:16.

Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;342:d549.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2003;327:557–60.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1997;315:629–34.

Abufaraj M, Tabung FK, Shariat SF, et al. Association between inflammatory potential of diet and bladder cancer risk: Results of 3 united states prospective cohort studies. J Urol. 2019;202:484–9.

Shivappa N, Hébert JR, Rosato V, et al. Dietary inflammatory index and risk of bladder cancer in a large Italian case-control study. Urology. 2017;100:84–9.

Shivappa N, Hébert JR, Mirsafa F, et al. Increased inflammatory potential of diet is associated with increased risk of bladder cancer in an Iranian case-control study. Nutr Cancer. 2019;71:1086–93.

Magalhães B, PeleteiroLunet BN. Dietary patterns and colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21:15–23.

Feng YL, Shu L, Zheng PF, et al. Dietary patterns and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. European journal of cancer prevention : the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP). 2017;26:201–11.

Bertuccio P, Rosato V, Andreano A, et al. Dietary patterns and gastric cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1450–8.

Fabiani R, Minelli L, Bertarelli G et al. (2016) A Western Dietary Pattern Increases Prostate Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 8.

Li F, An S, Hou L, et al. Red and processed meat intake and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:2100.

Crippa A, Larsson SC, Discacciati A, et al. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of bladder cancer: a dose–response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:689–701.

Xu L, Qu Y-H, Chu X-D, et al. Urinary levels of N-nitroso compounds in relation to risk of gastric cancer: findings from the shanghai cohort study. PloS one. 2015;10:e0117326.

Tappel A. Heme of consumed red meat can act as a catalyst of oxidative damage and could initiate colon, breast and prostate cancers, heart disease and other diseases. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:562–4.

Di Maso M, Turati F, Bosetti C, et al. Food consumption, meat cooking methods and diet diversity and the risk of bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;63:101595.

Lin J, Forman MR, Wang J, et al. Intake of red meat and heterocyclic amines, metabolic pathway genes and bladder cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1892–903.

Chiang VS-C, Quek S-Y. The relationship of red meat with cancer: Effects of thermal processing and related physiological mechanisms. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:1153–73.

Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Galbete C, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9:1063.

Cheng S, Zheng Q, Ding G, et al. Mediterranean dietary pattern and the risk of prostate cancer: A meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019;98:e16341.

Park SY, Ollberding NJ, Woolcott CG, et al. Fruit and vegetable intakes are associated with lower risk of bladder cancer among women in the Multiethnic Cohort Study. J Nutr. 2013;143:1283–92.

Vieira AR, Vingeliene S, Chan DS, et al. Fruits, vegetables, and bladder cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2015;4:136–46.

Pérez-Jiménez J, Diaz-RubioSaura-Calixto MEF. Contribution of macromolecular antioxidants to dietary antioxidant capacity: A Study in the Spanish Mediterranean Diet. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2015;70:365–70.

Lu D-L, Ren Z-J, Zhang Q, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between the inflammatory potential of diet and urologic cancer risk. PloS one. 2018;13:e0204845.

Ohnishi S, Ma N, Thanan R, et al. DNA damage in inflammation-related carcinogenesis and cancer stem cells. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2013;2013:387014.

Acknowledgements

The first author would acknowledge M. Saadatmnad and E. Ghasemi for their cooperation in searching databases. Though, they did not meet the authorship criteria to be listed as co-authors.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study. The study sponsors/universities had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D., E.F., A.A., and N.A., were involved in the study conceptualization, methodology, writing and editing the manuscript. M.D., and D.B. helped in data analysis and manuscript review. A.W., M.Z., and M.F. were involved in writing and editing the manuscript and providing critical feedback. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dianatinasab, M., Forozani, E., Akbari, A. et al. Dietary patterns and risk of bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 22, 73 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12516-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12516-2