Abstract

Background

Use of electronic data collection, management and analysis tools to support outbreak response is limited, especially in low income countries. This can hamper timely decision-making during outbreak response. Identifying available tools and assessing their functions in the context of outbreak response would support appropriate selection and use, and likely more timely data-driven decision-making during outbreaks.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and a stakeholder survey of the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network and other partners to identify and describe the use of, and technical characteristics of, electronic data tools used for outbreak response in low- and middle-income countries. Databases included were MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health, Web of Science and CINAHL with publications related to tools for outbreak response included from January 2010–May 2020. Software tool websites of identified tools were also reviewed. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied and counts, and proportions of data obtained from the review or stakeholder survey were calculated.

Results

We identified 75 electronic tools including for data collection (33/75), management (13/75) and analysis (49/75) based on data from the review and survey. Twenty-eight tools integrated all three functionalities upon collection of additional information from the tool developer websites. The majority were open source, capable of offline data collection and data visualisation. EpiInfo, KoBoCollect and Open Data Kit had the broadest use, including for health promotion, infection prevention and control, and surveillance data capture. Survey participants highlighted harmonisation of data tools as a key challenge in outbreaks and the need for preparedness through training front-line responders on data tools. In partnership with the Global Health Network, we created an online interactive decision-making tool using data derived from the survey and review.

Conclusions

Many electronic tools are available for data -collection, −management and -analysis in outbreak response, but appropriate tool selection depends on knowledge of tools’ functionalities and capabilities. The online decision-making tool created to assist selection of the most appropriate tool(s) for outbreak response helps by matching requirements with functionality. Applying the tool together with harmonisation of data formats, and training of front-line responders outside of epidemic periods can support more timely data-driven decision making in outbreaks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infectious disease outbreaks pose a serious global health challenge, as illustrated by the worldwide pandemic of COVID-19. In the last decade alone, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared six Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) associated with infectious diseases [1,2,3]. Low and middle-income countries (LMICs) with weaker health systems are particularly at risk with limited surveillance leading to late detection and response to outbreaks [4, 5]. During outbreaks, timely collection, management, sharing, analysis and reporting of data are required to ensure that interventions are appropriately targeted and effective in supporting outbreak control.

The use of information and communication technologies (ICT) for health - eHealth, is growing in importance as it facilitates access to and delivery of health services as well as collection, management and analysis of infectious and non-communicable disease data [6, 7]. Electronic tools and solutions offer many advantages over traditional paper-based data collection, including more rapid data collection and transfer, use of checks/validation to improve data accuracy, and collection of more diverse data types including images, audio and barcodes. They can provide cost savings and are more environmentally friendly [8,9,10,11]. However, electronic tools also have limitations in some contexts, for example if there are requirements for stable electricity, internet or phone connectivity.

Electronic tools can also be used during outbreaks to support timely collection and analysis of data. However, in practice, in outbreak response we have observed data are often collected on paper and day-to-day programs for analysis being used, foregoing tools better designed to meet needs. There are a growing number of tools available for use in outbreaks and emergencies [12, 13]. A recent review identified 58 mobile tools developed for, or used during, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2013–2016 [12]. There are however challenges to the use of electronic tools in outbreaks and emergencies. Emergencies require rapid deployment of frontline workers for data collection, and while there are now many electronic tools to support this, various similar tools for data collection may occur during the same outbreak at the same time in a fragmented manner, due to lack of coordination. The number of similar tools combined with the compressed timeframes can lead to little time for deliberation over optimal data collection methods. There are also requirements in these contexts - emergencies and outbreaks in LMICs often occur in settings with the most limited infrastructures and tools in these settings need to be flexible to function in these environments. They also need to be able to be incorporated into existing data or surveillance infrastructures and allow for interoperability and/or data sharing between organisations. Ideally, these electronic tools should be employed both for routine surveillance activities and outbreak response in an integrated, sustainable approach.

Choosing the most appropriate electronic tool for an outbreak response is important, but it is also essential to harmonise data collection and ensure interoperability. Some projects seek to support harmonisation of how we collect data independently of the tool we use, including the Humanitarian Exchange Language (HXL) and the WHO “Outbreak Toolkit” [14, 15]. Standardising the choice, format and/or naming/tagging of the data variables collected between and within organisations during outbreaks and humanitarian emergencies (such as through standardised case investigation forms, unique agreed reporting categories, standardised data formats and data dictionaries) facilitates more efficient data sharing and timelier data analyses for rapid decision making.

In outbreaks and emergencies, diverse technical characteristics are required for an electronic data system to support the most effective outbreak response. With limited time and resources, it is unsurprising that decision makers may have difficulty identifying the most appropriate tools for their needs. Here we aim to identify and describe characteristics of electronic data collection, management and analysis tools used for infectious disease outbreaks in LMICs, the functionalities most commonly required in outbreaks, in order to facilitate decision making on appropriate tool selection. We also aimed to make this information more easily accessible to relevant stakeholders through the creation of an interactive and dynamic online decision-making tool.

Methods

Search strategy

We followed PRISMA guidelines to conduct the systematic review [16]. We searched five electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health, Web of Science and CINAHL. The search terms included four categories: LMICs, outbreaks or epidemics or early warning alert and response or humanitarian emergencies, data management, collection and analysis and electronic tools. Search terms are listed in additional file 1 for all databases. The search strategies included indexed terms where possible. LMIC filters based on World Bank categorizations were used from Ovid [17].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies if they described electronic data collection, management or analysis tools that were used in low- and middle-income countries either for detection or response to an infectious disease outbreak (animal or human) alone or as part of a humanitarian emergency, or as part of an early warning and alert system. In addition, studies that analysed outbreak data or performed operational disease modelling analyses were included. Studies published from 1st January 2010 to 12th October 2018 in English, French, German, Portuguese or Spanish were included. An update of the original search was conducted which included studies published from October 2018 to May 2020.

We excluded studies that described non-communicable diseases or drug epidemics, clinical trials in outbreaks; seroprevalence studies; qualitative studies, unless directly linked to data tools for collection, management and analysis of outbreak or outbreak-related humanitarian data. Studies that focused on retrospective analysis of infectious disease surveillance data to identify outbreaks as well as articles describing electronic data tools without any operational application to outbreak response were also excluded. Similarly, modelling analyses based on surveillance or simulated data as well as tools for humanitarian response or preparedness without any link to outbreak response were excluded. Hospital information management tools, unless specifically developed for an outbreak, were also excluded. Review articles and studies for which full text articles were not available open access were also excluded.

Identification of potentially eligible studies

We exported identified studies to Endnote (version 8, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA) and removed any duplicates. Two authors (PK and JM) independently assessed the relevance of all titles and abstracts based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the case of differing views on the inclusion of an article, consensus was reached by discussion between the two researchers. Full-text articles were retrieved for all potentially relevant studies. Two authors (PK and JM) independently assessed the full text articles using the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

We extracted information, using a standardised form, on the electronic tools from the included articles examining cost, license type, compatibility with windows, mac and linux, location of data storage, ability to visualise data, whether data could be collected with a mobile application (also the type of mobile devices that could be used for data collection) or via a web interface, data encryption functionality, collection of GPS data, and ability to collect data offline (see additional file 2 for the definitions used for the data extraction). We supplemented data from the systematic review with additional detail on technical capacities and overall functions either via direct contact with the electronic tool developers and/or reading information provided in their websites.

Stakeholder survey

To identify electronic tools used in recent outbreaks in LMICs, we invited key stakeholders, such as Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) members which includes National Public Health Institutes, Ministries of Health, United Nations Agencies, National and international laboratory teams, non-governmental organisations (e.g. Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières), Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Interventions Network (TEPHINET) and related Field Epidemiology Training Programmes to participate in an online survey (created using Enketo and available in English and French) in May 2019 (see additional file 3 for the data dictionary of the survey). To be eligible to complete the survey, participants needed to have responded to outbreaks in World Health Organisation (WHO) grade two or three priority countries that included Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Pakistan, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey/North Syria, Ukraine and Yemen. We selected these countries to identify tools that had been used in recent outbreaks during acute or protracted emergencies. We asked participants to identify the electronic data collection, management and analysis tools used during the outbreaks and to specify what they used the tools for. We focused on key pillars of outbreak response and asked participants to specify which electronic tools they used to collect/manage and analyse alert, case investigation, contact tracing, health promotion, case management, infection, prevention and control, laboratory, surveillance, clinical trial and water and sanitation data. We also asked participants their reasons for selecting the specific tool, and for any suggestions on how to improve the tools. In addition, participants were asked to rank and comment on data collection challenges in outbreaks.

Data analysis

Counts and proportions of data obtained either from the systematic review or the stakeholder survey were calculated using R version 3.6.1, R Foundation for Statistical Learning, Vienna, Austria. Text data from the stakeholder survey were analysed by reviewing responses and identifying the most frequently shared views.

Results

Identification of electronic tools - systematic review and stakeholder survey

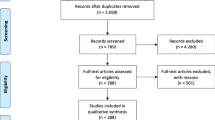

We identified 5773 studies from the five selected databases across the period 2010–2020 and after deduplication, 4503 potentially relevant studies remained. We screened full-text articles for 321 studies, of which 80 were included [11, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96] (see additional file 4 for a list of excluded studies and the reasons for exclusion). From 80 studies included, we identified 64 unique electronic data tools (Fig. 1). Of these 80 studies, twelve, eleven, five and three studies were focused on Ebola, Dengue, Cholera and COVID-19, respectively. Four and six studies described animal outbreaks and early warning systems, respectively. Six custom-made applications were also among the included studies. Among the 64 tools reported, 12 were identified through the update to the systematic review from 2018 to 2020. No major differences were observed in terms of the types of tools (i.e. similar proportions of data collection, management and analysis tools were found in both periods) identified in the periods 2010–2018 and 2018 and 2020.

PRISMA flow chart for systematic literature review (2010–2020) [16]

Fifty-five individuals consented to complete the online stakeholder survey, of which 41 were eligible for inclusion. Four Ministries of Health and sixteen organisations were represented, of which Doctors Without Borders and the WHO made up 22% (n = 9) each of the eligible survey respondents (see additional file 5 for a summary of all organisations that participated). The Democratic Republic of Congo (n = 20), Nigeria (n = 11) and Bangladesh (n = 10) were the countries most frequently mentioned for outbreak response by respondents. However, respondents had been involved in outbreak response in 17 out of the 20 listed countries. Epidemiologists represented the majority of survey respondents (59%, n = 24). Respondents reported working at international, national, regional and field levels, with the majority (51%, n = 21) working at field level. Twenty-nine unique tools were reported in the stakeholder survey and after deduplication with the tools identified from the systematic review, 75 tools were included in this study for further characterisation (Fig. 1).

Uses of electronic data tools

The 75 identified tools reported in the systematic review and survey covered data collection [33], management [13] and analysis [49] activities as detailed in Table 1. Of note, many of the tools could be used for collection and/or management and/or analysis and almost half of the analysis tools related to analysis/visualisation of sequencing data. In the following paragraphs the proportion of data collection, management and analysis tools in terms of their uses and other characteristics is calculated, but these calculations exclude tools for which it was not possible to ascertain if the tool had the specific use/characteristic or not. For data collection tools, surveillance was the most frequently reported use (81%, n = 25), followed by case management and health promotion (69% and 54%, respectively). Electronic data collection tools were less frequently reported as being used for collection of infection, prevention and control data (25%, n = 6) and for WASH assessments (30%, n = 7). For data management, the majority of the thirteen reported data management tools allowed data cleaning, survey generation and more general data management functionality. For data analysis, of the 49 identified data analysis tools, data visualisation (72%, n = 21) and mapping (69%, n = 18) were the most commonly reported uses and phylogenetic analysis the least (43%, n = 13).

The reported uses of electronic data collection, management and analysis tools in outbreak response identified in the systematic review and stakeholder survey are given in Fig. 2a, b and c for each tool respectively. Epi Info, KoBoCollect and ODK were the tools most widely reported in use to collect a range of outbreak data, followed closely by DHIS2 and EWARS (Fig. 2a). There were fewer differences across reported data management tools and MS Access, Excel, EWARS and Epi Data offered the same number of functionalities (Fig. 2b). Among data analysis tools, ArcGIS, R, SAS and Stata were reported as being used with the greatest diversity of functions (Fig. 2c). See additional file 6 for a summary of the tools that organisations with at least two respondents reported. The number of uses identified per tool varied depending on whether the tool was reported in the survey and/or the systematic review, such that tools reported in the systematic review only generally had fewer reported uses (see additional file 7 for a breakdown of where tools were identified from, the period of the systematic review and their reported uses).

Characteristics of electronic data tools

With further investigation via contacting tool developers or through the tool websites, we found that many of the tools identified in the review and stakeholder had more functionalities and uses compared to data obtained from the survey and review alone. Twenty-eight out of the 75 identified tools could perform data collection, management and analysis functions to a greater or lesser extent in comparison to seven tools based on data only available in the review and survey. The 28 tools that incorporate data collection, management and analysis functionalities (Table 2) have overlapping characteristics, with 90% (n = 18) of tools supporting data encryption, 88% (n = 23) offering data visualisation and 85% (n = 22) providing web data entry functionalities. In addition, we found the majority of tools were compatible with Windows (100%) and Apple (85%). However, only 63% (n = 15) are open source software and 87% (n = 20) of the software are free (see additional file 8 for more detailed information per tool).

Factors influencing tool selection

Survey participants were asked an open question on what influenced their choice of tool, and 10 factors emerged as key influencers: [1] cost [2]; user friendliness [3]; speed to configure data collection forms/deploy the system [4]; availability of the tool [5]; previous experience with a tool either by individuals, within specific organisations or by Ministry of Health personnel [6]; open source tool [7]; offline use [8]; availability of specific functionalities e.g. audit log [9]; if the tool was viewed as the “sector standard” and [10] presence of a strong userbase/community of support.

Improving currently available tools

Survey participants were also asked another open question to comment on how their currently used electronic tools could be improved. Ten improvements were recommended: [1] reduce the cost [2]; improve the interoperability [3]; improve user-friendliness [4]; increase the flexibility and customisability of the tool, which would reduce the reliance of local staff on centralised teams/deployment of specialists [5]; provide more training resources and in more languages, with a suggestion to build training modules within the tools [6]; simplify the local hosting procedures [7]; improve data visualisations [8]; allow more advanced analyses to be performed [9]; improve multiple user management and [10] improve support for longitudinal data.

Data collection challenges in outbreaks

Survey respondents’ were asked to rank nine potential data collection challenges during outbreaks in LMICs, which were based on the experiences of the authors: [1] ensuring data confidentiality [2]; harmonisation of data tools [3]; operating in insecure environments [4] lack of or limited internet access [5]; language barriers [6]; physical access to populations/areas [7]; lack of or limited power supply [8]; community resistance and [9] lack of or limited telecommunications/mobile connectivity. Based on the median ranking score, respondents rated harmonisation of data tools as the most difficult challenge of those listed, but there was overlap with other challenges including operating in insecure environments and lack of or limited internet access. Respondents were also asked to comment on other data collection challenges and provide any further reflections on electronic tools and highlighted the following: [1] integrated electronic tools should be capable of doing all the basics for outbreak response with minimal training [2]; there is a need for greater coordination of responding organisations including around tool/template and data sharing [3]; there is insufficient training of data collectors including on how the data collected would be used [4]; the need to provide training on electronic tools outside of outbreak periods and to focus on getting the basics right and [5] feedback loop ensuring that data collection teams can see or access the results/analyses.

Discussion

Capturing accurate, timely data on outbreaks is central to any outbreak response and highlighted further during the COVID-19 pandemic, as it allows timely decision making on response activities, whether localised or worldwide. The COVID-19 pandemic alone has led to the development of a number of new tools for contact tracing and other purposes used across multiple settings, although primarily in high-income countries, but also raised concerns about data protection/security [97]. We identified a wide range of electronic tools to support data collection, management and analysis in outbreak response. Key requirements for tools selected at present include availability and whether training is needed, as well as cost, and if the software is open source. This may lead to use of tools without the optimal functionalities for outbreak response as most members of an outbreak response team, including non-analytical staff, are familiar with standard software. Specifically designed and integrated tools, can better support outbreak investigation across data collection, management and analysis. With more advanced analytics being incorporated into outbreak response and with data management being an integral part of data analysis, ease of use should not drive choice [98]. Analytic tools used in an emergency should ideally be part of routinely used surveillance software or at least be compatible with and complement such routine surveillance software. In addition, analytic tools should also reflect the analysis and data management required for outbreak control. Supporting decision makers to consider and match the functionalities of a tool, with their requirements, is a key part of enabling optimal use of tools, as well as overcoming practical constraints through preparedness, to support training and implementation.

We identified electronic tools in the published literature as well as tools organisations recently used in outbreak response in LMICs. However, the diversity of information may be limited by the responses to the survey, which was sent out to GOARN members (200 technical institutes and over 600 partners worldwide), with only 20 organisations (four Ministries of Health from LMICs) completing the survey [99]. In addition, the majority of respondents were epidemiologists from international organisations including MSF and the WHO and thus the results may not fully reflect the electronic tools being used across different pillars in outbreak response nor those used routinely in LMICs for outbreaks in which international organisations do not get involved. The survey did, however, support identification of tools in the grey literature, which also formed a key part of the findings of a recent review on tools used in the Ebola outbreak [12]. In addition, the period covered by this study included the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic but we only identified one novel tool developed to support COVID-19 response [25]. This tool called the Honghu Hybrid System incorporated clinical, laboratory and social media platform data to help COVID-19 surveillance and control. It is likely that the Honghu Hybrid System is one of many such tools that have been developed since the start of the pandemic and a COVID-19 specific review would enable the identification of further such innovations.

Despite these limitations, we identified a wide range of tools, and showed that tools which are open source are important, as well as training to support their use. Outbreak response personnel, especially front-line workers, must be trained in the use of integrated tools that can perform key basic analyses to support rapid decision making. Training on such tools during non-emergency periods is thus vital. Training initiatives such as the DHIS2 academy enable individuals to build capacity in the implementation of DHIS2 at national and higher levels outside periods of outbreaks/emergencies [100]. Similar training initiatives could be used to strengthen capacity of front-line workers on other outbreak deployment tools and factors such as DHIS2-compatibility, being open source and having large and diverse community user bases could help narrow the scope of tools for such initiatives. Moreover, it would enable the identification of tools more likely to be maintained and developed compared to the use of more niche tools. It was surprising to find a small number of tools created for specific projects such as the AVADAR, mHealthSurvey, OlympTRIP and the Institut Pasteur applications [57, 59, 85, 101]. Through investment in existing open-source tools, researchers and Ministries of Health could add new functionalities to these tools benefitting larger user communities and limiting the proliferation of electronic tools with similar functionalities. In addition, inclusion of regularly updated training modules (in multiple languages) within the tools themselves could offer opportunities to strengthen capacity of front-line workers during non-emergency periods.

The large number of tools for data collection, management and analysis, with similar functionalities (and limited economic evaluation) makes it difficult for decision makers to select the most appropriate tool for their needs. This range of tools has both advantages and disadvantages, as no one tool may be suitable for all types of outbreaks across multiple different contexts. Therefore, decision makers would benefit from support to match the functionalities of tools with their specific requirements and contexts. To address this point, from this study, we created an online decision-making tool (https://uk-phrst.tghn.org/tools-platforms/tools/data-tool-finder-app/) based on data collected from this study to support organisations to identify the most appropriate tool(s) for their needs (based on data in additional file 8). The online decision-making tool enables users to select electronic tools based on their requirements, rate tools they have already used and to make suggestions of any extra tools to include in the decision-making tool. This will allow it to both identify better performing tools and to remain up to date with electronic tools being used and developed for outbreak response in LMICs. Users can take into consideration factors such as the cost, the license type, availability of a mobile application, ability to perform data visualisation and location where data are hosted.

The need for better data harmonisation and improved interoperability between tools was another key finding of this study. Improving the interoperability and harmonisation between outbreak data collection tools and broader Health Information Systems facilitating routine surveillance activities (such as DHIS2) is important. Harmonising use of data tools within and between organisations, supporting training and improving interoperability remain key to improving uptake and use of electronic tools in outbreak response in LMICs. Harmonising electronic tool use across regions would allow for the roll out of standardised training to regional and national rapid response teams and thus improve their ability to support each other during outbreaks. The current COVID-19 pandemic illustrates this further and that it is not just in LMICs where harmonisation of tools and training is required but it would be highly beneficial in all countries. All pillars of the COVID-19 response rely on data to inform interventions/actions taken from case management, contact tracing, risk communication to infection prevention and control and a harmonisation of data formats, tools and training would save countries time and financial resources.

Improving the consistency of the choice and format of data collected in emergencies is recognised internationally [14, 15]. Using the same data templates would greatly facilitate management, analysis and sharing of data and thus more rapid and better-informed decision making. Enabling more rapid sharing of data during a pandemic such as COVID-19 within and between countries would further support more rapid and appropriate decision making. In addition, ensuring that data collectors know why they are collecting the data, how it will be used and have access to the results are all important in maintaining motivation to work in challenging outbreak environments.

In conclusion, a multi-faceted approach that considers both the type and format of data being collected, the use of integrated electronic tools that ideally function both for routine surveillance and outbreak response as well as a focus on training and ongoing capacity strengthening on data collection, management and analyses is needed to address this most urgent challenge.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets created as part of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Soghaier MA, Saeed KM, Zaman KK. Public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) has declared twice in 2014; polio and Ebola at the top. AIMS Public Heal. 2015;2(2):218–22. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2015.2.218.

Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. [cited 2019 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/17-07-2019-ebola-outbreak-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-declared-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern

WHO. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov).

WHO | Top 10 causes of death. [cited 2019 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/causes_death/top_10/en/

Hoffman SJ, Silverberg SL. Delays in global disease outbreak responses: Lessons from H1N1, Ebola, and Zika. American Journal of Public Health. 2018;108:329–33 American Public Health Association Inc.

mHealth Use of appropriate digital technologies for public health. 2018; Available from: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTINFORMATIONANDCOMMUNICATIONANDTECHNO. [cited 2019 Oct 3]

Aranda-Jan CB, Mohutsiwa-Dibe N, Loukanova S. Systematic review on what works, what does not work and why of implementation of mobile health (mHealth) projects in Africa. BMC Public Health. 2014 Feb;14(1):188. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-188.

Pakhare AP, Bali S, Kalra G. Use of Mobile Phones as Research Instrument for Data Collection. Indian J Commun Health. 2013;25 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279853939. [cited 2019 Oct 3].

Flaxman AD, Stewart A, Joseph JC, Alam N, Alam SS, Chowdhury H, et al. Collecting verbal autopsies: improving and streamlining data collection processes using electronic tablets. Popul Health Metrics. 2018;16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-018-0161-9.

Njuguna HN, Caselton DL, Arunga GO, Emukule GO, Kinyanjui DK, Kalani RM, et al. A comparison of smartphones to paper-based questionnaires for routine influenza sentinel surveillance, Kenya, 2011–2012. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:107 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med8&NEWS=N&AN=25539745.

Guo Y, Su XM. Mobile device-based reporting system for Sichuan earthquake-affected areas infectious disease reporting in China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2012;25(6):724–9 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medc&NEWS=N&AN=23228844.

Tom-Aba D, Nguku PM, Arinze CC, Krause G. Assessing the concepts and designs of 58 Mobile apps for the management of the 2014-2015 West Africa Ebola outbreak: systematic review. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2018;4(4):e68. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.9015.

Carroll LN, Au AP, Detwiler LT, Fu TC, Painter IS, Abernethy NF. Visualization and analytics tools for infectious disease epidemiology: a systematic review. J Biomed Inform. 2014;51:287–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2014.04.006.

Outbreak toolkit. [cited 2019 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/outbreak-toolkit

OCHA. hxlstandard. Available from: https://hxlstandard.org

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [cited 2019 Nov 27], Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

New country classifications by income level: 2017–2018 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Oct 3]. Available from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2017-2018

El Hamouchi A, Daoui O, Ait Kbaich M, et al. Epidemiological features of a recent zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis outbreak in Zagora province, southern Morocco. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(4):e0007321. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007321. Published 2019 Apr 9.

Naveca FG, Claro I, Giovanetti M, et al. Genomic, epidemiological and digital surveillance of Chikungunya virus in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(3):e0007065. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007065. Published 2019 Mar 7.

Yan H, Ding Z, Yan J, Yao W, Pan J, Yang Z, et al. Epidemiological characterization of the 2017 dengue outbreak in Zhejiang, China and molecular characterization of the viruses. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:216 Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00216/full.

Neto OL, Cruz O, Albuquerque J, de Sousa MN, Smolinski M, Pessoa Cesse EA, et al. Participatory surveillance based on crowdsourcing during the Rio 2016 Olympic games using the guardians of health platform: descriptive study. JMIR PUBLIC Heal Surveill. 2020;6(2):82–96.

Brumboiu MI, Poolay MC. The capture-recapture method in the analysis of a measles epidemic in the county of Cluj, Romania. Appl Med Informatics [Internet]. 2019;41(4):140–6 Available from: https://ami.info.umfcluj.ro/index.php/AMI/article/view/701.

Swanson KC, Altare C, Wesseh CS, Nyenswah T, Ahmed T, Eyal N, et al. Contact tracing performance during the Ebola epidemic in Liberia, 2014–2015. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(9).

Karo B, Haskew C, Khan AS, Polonsky JA, Mazhar MK. World health organization early warning, alert and response system in the Rohingya crisis, Bangladesh, 2017–2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(11):2074–6 Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/24/11/pdfs/18-1237.pdf.

M. G, L. L, X. S, Y. Y, S. W, Zhu H. AO - Gong Li; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5188-2408 AO - Yang, Yue; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9825-2614 AO - Zhu, Hong; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9969-3542 AO - Sun, Xin; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6554-7088 AO - MO http://orcid.org/000-0001-8197-6643 AO-L. Cloud-Based System for Effective Surveillance and Control of COVID-19: Useful Experiences From Hubei, China. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2020;22(4):e18948. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexb&NEWS=N&AN=631520721

Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=32217556.

Wijayanti SP, Nurlaela S, Octaviana D, Putra FA, Nurhayati S. Dengue virus transmission during outbreak within endemic area in Indonesia : A spatial and temporal analysis. Ann Trop Med Public Heal. 2019;22(11):S320 Available from: http://www.atmph.org.

S. F, K.A. G, Chunara R. AO - Grepin Rumi; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5346-7259 KA. O http://orcid.org/000-0003-4368-0045 AO-C. Tracking health seeking behavior during an Ebola outbreak via mobile phones and SMS. npj Digit Med [Internet]. 2018;1(1):51. Available from: https://www.nature.com/npjdigitalmed/

Zheng S, Fan J, Yu F, Feng B, Lou B, Zou Q, et al. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January–March 2020: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=32317267.

Davies C, Graffy R, Shandukani M, Baloyi E, Gast L, Kok G, et al. Effectiveness of 24-h mobile reporting tool during a malaria outbreak in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Malar J. 2019;18(1):45 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med16&NEWS=N&AN=30791909.

Chien L-C, Lin R-T, Liao Y, Sy FS, Perez A, et al. Surveillance on the endemic of Zika virus infection by meteorological factors in Colombia: a population-based spatial and temporal study. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(180):180 Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12879-018-3085-x.

Braga JM, Nhantumbo L, Nhambomba A, Cossa E, Nhabomba C, Dimas T, et al. Epidemiological profile of health consultations during the Mozambique 9th national cultural festival, August 2016. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33:52 Available from: http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/33/52/pdf/52.pdf.

Rude JM, Kortimai L, Mosoka F, April B, Nuha M, Katawera V, et al. Rapid response to meningococcal disease cluster in Foya district, Lofa County, Liberia January to February 2018. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33(Suppl 2):6 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexa&NEWS=N&AN=629072119.

Wawina-Bokalanga T, Vanmechelen B, Martí-Carreras J, Vergote V, Vermeire K, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, et al. Complete genome sequence of a new Ebola virus strain isolated during the 2017 Likati outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2019;8(20):e00360–19 Available from: https://mra.asm.org/content/ga/8/20/e00360-19.full.pdf.

Dureab F, Ismail O, Müller O. Cholera outbreak in Yemen: Timeliness of reporting and response in the national electronic disease early warning system. Acta Inform Medica. 2019;27(2):85–8 Available from: https://actainformmed.org/.

Li Z, Fu J, Lin G, Jiang D. Spatiotemporal Variation and Hotspot Detection of the Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus in China, 2013–2017. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(4):648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040648. Published 2019 Feb 22.

Jabeen U, Iftikhar A, Hamid MH, Chaudhry A. Comparison of characteristics of dengue hemorrhagic fever in children during 2011 and 2013 outbreaks. Pak Pediatr J. 2018;42(2):95–100 Available from: http://pakpedsjournal.org.pk/Journals.aspx.

Hussain-Alkhateeb L, Kroeger A, Olliaro P, Rocklov J, Sewe MO, Tejeda G, et al. Early warning and response system (EWARS) for dengue outbreaks: Recent advancements towards widespread applications in critical settings. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196811 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emexb&AN=621978385.

Liu Y, Hu J, Snell-Feikema I, MS VB, Lamsal A, Wimberly MC. Software to facilitate remote sensing data access for disease early warning systems. (Special Section: Modelling health risks.). Environ Model Softw. 2015;74:247–57. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=cagh&AN=20153425390https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:caghdb&id=doi:10.1016%2Fj.envsoft.2015.07.006&id=pmid&issn=1364-8152&isbn=&volume=74&issue=&sp.

Qiu H, Wu J, Hong L, Luo Y, Song Q. Clinical and epidemiological features of 36 children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Zhejiang, China: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020; Available from: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/the-lancet-infectious-diseases.

Osuorah D, Shah B, Manjang A, Secka E, Ekwochi U, Ebenebe J. Outbreak of serotype W135 Neisseria meningitidis in central river region of the Gambia between February and June 2012: a hospital-based review of paediatric cases. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015;18(1):41–7 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed16&AN=604579198https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.4103%2F1119-3077.146977&id=pmid25511342&issn=1119-3077&isbn=&volume=18&issue=.

Caceres VM, Cardoso P, Sidibe S, Lambert S, Lopez A, Pedalino B, et al. Daily zero-reporting for suspect Ebola using short message service (SMS) in Guinea-Bissau. Public Health [Internet]. 2016;138:69–73. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed17&AN=610047638https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1016%2Fj.puhe.2016.03.006&id=pmid27106280&issn=0033-3506&isbn=&volume=138&iss. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.006.

Munyua PM, Hightower A, Mbabu MR, Ithondeka P, Anyangu SA, Breiman RF, et al. Rift valley fever disease risk map for Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;1:16 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed13&AN=71040680https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:&id=pmid&issn=0002-9637&isbn=&volume=87&issue=5+SUPPL.+1&spage=16&pages=16&date=2.

Ahmad S, Asif M, Talib R, Adeel M, Yasir M, Chaudary MH. Surveillance of intensity level and geographical spreading of dengue outbreak among males and females in Punjab, Pakistan: A case study of 2011. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(4):472–85 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emexa&AN=619439729https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1016%2Fj.jiph.2017.10.002&id=pmid&issn=1876-0341&isbn=&volume=11&issue=4&spage.

Sigudu TT, Tint KS, Archer B. Epidemiological description of cholera outbreak in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa, December 2008-march 2009. S Afr J Epidemiol Infect. 2015;30(4):18–21 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed16&AN=607329616https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1080%2F23120053.2015.1107263&id=pmid&issn=1015-8782&isbn=&volume=30&issue=4&s.

Jobanputra K, Greig J, Shankar G, Perakslis E, Kremer R, Achar J, et al. Electronic medical records in humanitarian emergencies - the development of an Ebola clinical information and patient management system [version 1; referees: 1 approved, 1 approved with reservations]. F1000Research. 2016;5:1477 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed17&AN=614208916https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.12688%2FF1000RESEARCH.8287.1&id=pmid&issn=2046-1402&isbn=&volume=5&issue=&spa.

Vicente CR, Herbinger KH, Junior CC, Romano CM, De Souza Areias Cabidelle A, Froschl G. Determination of clusters and factors associated with dengue dispersion during the first epidemic related to Dengue virus serotype 4 in Vitoria, Brazil. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175432 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed18&AN=615215921https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0175432&id=pmid28388694&issn=1932-6203&isbn=&volume=12&is.

Chunara R, Chhaya V, Bane S, Mekaru SR, Chan EH, Freifeld CC, et al. Online reporting for malaria surveillance using micro-monetary incentives, in urban India 2010–2011. Malar J. 2012;43 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emexb&AN=51863085https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1186%2F1475-2875-11-43&id=pmid22330227&issn=1475-2875&isbn=&volume=11&issue=1&s.

Weekly epidemiological record. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92(5):45–52 Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,shib&db=rzh&AN=121128684&site=ehost-live.

Quesada-Gomez C, Lopez-Urena D, Acuna-Amador L, Villalobos-Zuniga M, Du T, Freire R, et al. Emergence of an outbreak-associated Clostridium difficile variant with increased virulence. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(4):1216–26 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed16&AN=603212836https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1128%2FJCM.03058-14&id=pmid&issn=0095-1137&isbn=&volume=53&issue=4&spage=1216.

Yano T, Phornwisetsirikun S, Susumpow P, Visrutaratna S, Chanachai K, Phetra P, et al. A participatory system for preventing pandemics of animal origins: pilot study of the participatory one health disease detection (PODD) system. JMIR PUBLIC Heal Surveill. 2018;4(1):304–14. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.7375.

Pinchoff J, Chipeta J, Banda GC, Miti S, Shields T, Curriero F, et al. Spatial clustering of measles cases during endemic (1998–2002) and epidemic (2010) periods in Lusaka, Zambia. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):121 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed16&AN=603523071https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1186%2Fs12879-015-0842-y&id=pmid25888228&issn=1471-2334&isbn=&volume=15&issue.

Kamadjeu R, Gathenji C. Designing and implementing an electronic dashboard for disease outbreaks response - Case study of the 2013–2014 Somalia Polio outbreak response dashboard. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27(Supplement 3):22 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emexa&AN=620723882https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.11604%2Fpamj.supp.2017.27.3.11062&id=pmid29296157&issn=1937-8688&isbn=&volume=.

Osmani MG, Ward MP, Giasuddin M, Islam MR, Kalam A. The spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza (subtype H5N1) clades in Bangladesh, 2010 and 2011. Prev Vet Med 2014;114(1):21–27. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed15&AN=1052980273, https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1016%2Fj.prevetmed.2014.01.010&id=pmid24485276&issn=0167-5877&isbn=&volume=1, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2014.01.010

Null N, Agua-Agum J, Ariyarajah A, Aylward B, Bawo L, Bilivogui P, et al. Exposure Patterns Driving Ebola Transmission in West Africa: A Retrospective Observational Study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(11):1–23 Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,shib&db=rzh&AN=119471479&site=ehost-live.

Xu H, Gao X, Bo F, Ma J, Li Y, Fan C, et al. A rubella outbreak investigation and BRD-II strain rubella vaccine effectiveness study, Harbin city, Heilongjiang province, China, 2010-2011. Vaccine. 2013;32(1):85–9. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed14&AN=52864404https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1016%2Fj.vaccine.2013.10.070&id=pmid24188756&issn=0264-410X&isbn=&volume=32&is. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.070.

Rodriguez-Valero N, Oroz ML, Sanchez DC, Vladimirov A, Espriu M, Vera I, et al. Mobile based surveillance platform for detecting Zika virus among Spanish Delegates attending the Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201943 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emexb&AN=623570427https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0201943&id=pmid&issn=1932-6203&isbn=&volume=13&issue=8&spa.

Ramesh Masthi NR, Madhusudan M, Puthussery YP. Global positioning system & Google earth in the investigation of an outbreak of cholera in a village of Bengaluru Urban district, Karnataka. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142(NOVEMBER):533–7 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed16&AN=607237835https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.4103%2F0971-5916.171277&id=pmid&issn=0971-5916&isbn=&volume=142&issue=NOVEMBE.

Girond F, Randrianasolo L, Randriamampionona L, Rakotomanana F, Randrianarivelojosia M, Ratsitorahina M, et al. Analysing trends and forecasting malaria epidemics in Madagascar using a sentinel surveillance network: a web-based application. Malar J. 2017;16(1):1–11 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed18&AN=614416764https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:10.1186%2Fs12936-017-1728-9&id=pmid28193215&issn=1475-2875&isbn=&volume=16&issue.

Li Y, Guo H, Xu Z, Zhou X, Zhang H, Zhang L, et al. An outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis associated with a secondary water supply system in a factory in south China. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:283 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed14&AN=563086081https://discover.lshtm.ac.uk/openurl/44HYG/44HYG_services_page?sid=OVID:embase&id=doi:&id=pmid23537289&issn=1471-2458&isbn=&volume=13&issue=&spage=283&pages=283&date=.

Stewart-Ibarra AM, Muñoz AG, Ryan SJ, Ayala EB, Borbor-Cordova MJ, Finkelstein JL, et al. Spatiotemporal clustering, climate periodicity, and social-ecological risk factors for dengue during an outbreak in Machala, Ecuador, in 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):610 Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,shib&db=rzh&AN=109727911&site=ehost-live.

Xuan Z, DeGuang K, Jing L, BeiBei P, Ying Z, JunBo Z, et al. An outbreak of gastroenteritis associated with GII.17 norovirus-contaminated secondary water supply system in Wuhan, China, 2017. Food Environ Virol. 2019;11(2):126–37 Available from: http://rd.springer.com/journal/12560.

Schafer IJ, Knudsen E, McNamara LA, Agnihotri S, Rollin PE, Islam A, et al. The epi info viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF) application: a resource for outbreak data management and contact tracing in the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic. Ebola outbreak West Africa. 2016;214(Suppl. 3):S122–36. Available from: http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/214/suppl_3/S122.full. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiw272.

Jeefoo P, Tripathi NK, Souris M. Spatio-temporal diffusion pattern and hotspot detection of dengue in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011 Jan;8(1):51–74. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8010051.

Carbajo AE, Rubio A, Viani MJ, Colombo MR. The largest dengue outbreak in Argentina and spatial analyses of dengue cases in relation to a control program in a district with sylvan and urban environments. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2018;11(3):227–34. https://doi.org/10.4103/1995-7645.228438.

White P, Saketa S, Johnson E, Gopalani SV, Edward E, Loney C, et al. Mass gathering enhanced syndromic surveillance for the 8th Micronesian Games in 2014, Pohnpei State, Federated States of Micronesia. West Pac Surveill Res J. 2018;9(1):1–7 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=29666748.

Lee SS, Wong NS. The clustering and transmission dynamics of pandemic influenza a (H1N1) 2009 cases in Hong Kong. J Infect. 2011;63(4):274–80. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med7&NEWS=N&AN=21601284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2011.03.011.

Oyas H, Holmstrom L, Kemunto NP, Muturi M, Mwatondo A, Osoro E, et al. Enhanced surveillance for Rift Valley Fever in livestock during El Nino rains and threat of RVF outbreak, Kenya, 2015–2016. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(4):e0006353 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=29698487.

Ohene-Adjei K, Kenu E, Bandoh DA, Addo PNO, Noora CL, Nortey P, et al. Epidemiological link of a major cholera outbreak in Greater Accra region of Ghana, 2014. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):801 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=29020965.

Oza S, Jazayeri D, Teich JM, Ball E, Nankubuge PA, Rwebembera J, et al. Development and Deployment of the OpenMRS-Ebola Electronic Health Record System for an Ebola Treatment Center in Sierra Leone. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(8):e294 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medc&NEWS=N&AN=28827211.

Yan L, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Tildesley M, Liu L, Zhang Y, et al. Epidemiological and virological characteristics of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) school outbreaks in China in 2009. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45898 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med7&NEWS=N&AN=23029300.

Li Y, Fang L, Gao S, Wang Z, Gao H, Liu P, et al. Decision support system for the response to infectious disease emergencies based on WebGIS and mobile services in China. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54842 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medc&NEWS=N&AN=23372780.

K. C, A. K. Healthcare impact of COVID-19 epidemic in India: A stochastic mathematical model. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020; Available from: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/Medical-Journal-Armed-Forces-India

Madhanraj K, Singh N, Gupta M, Singh MP, Ratho RK. An outbreak of rubella in Chandigarh, India. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51(11):897–9. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med8&NEWS=N&AN=25432219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-014-0523-8.

Horwood PF, Karl S, Mueller I, Jonduo MH, Pavlin BI, Dagina R, et al. Spatio-temporal epidemiology of the cholera outbreak in Papua New Guinea, 2009–2011. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:449 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med8&NEWS=N&AN=25141942.

Liu W, Yang K, Qi X, Xu K, Ji H, Ai J, et al. Spatial and temporal analysis of human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in China, 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(47) Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med7&NEWS=N&AN=24300887.

Gleason BL, Foster S, Wilt GE, Miles B, Lewis B, Cauthen K, et al. Geospatial analysis of household spread of Ebola virus in a quarantined village - Sierra Leone, 2014. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(14):2921–9. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medc&NEWS=N&AN=28826426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268817001856.

Nic Lochlainn LM, Gayton I, Theocharopoulos G, Edwards R, Danis K, Kremer R, et al. Improving mapping for Ebola response through mobilising a local community with self-owned smartphones: Tonkolili District, Sierra Leone, January 2015. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189959 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=29298314.

Nsoesie EO, Ricketts RP, Brown HE, Fish D, Durham DP, Ndeffo Mbah ML, et al. Spatial and Temporal Clustering of Chikungunya Virus Transmission in Dominica. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(8):e0003977 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med8&NEWS=N&AN=26274813.

Farinelli EC, Baquero OS, Stephan C, Chiaravalloti-Neto F. Low socioeconomic condition and the risk of dengue fever: a direct relationship. Acta Trop. 2018;180:47–57. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=29352990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.01.005.

Pakhare A, Sabde Y, Joshi A, Jain R, Kokane A, Joshi R. A study of spatial and meteorological determinants of dengue outbreak in Bhopal City in 2014. J Vector Borne Dis. 2016;53(3):225–33 Available from: http://www.nimr.org.in/assets/533225.pdf.

Carroll MW, Matthews DA, Hiscox JA, Elmore MJ, Pollakis G, Rambaut A, et al. Temporal and spatial analysis of the 2014-2015 Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa. Nature. 2015;524(7563):97–101. Available from: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v524/n7563/full/nature14594.html. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14594.

Janani MK, Malathi J, Madhavan HN. Isolation of a variant human adenovirus identified based on phylogenetic analysis during an outbreak of acute keratoconjunctivitis in Chennai. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136(2):260–4 Available from: http://www.ijmr.org.in/article.asp?issn=0971-5916.

Peak CM, Wesolowski A, zu Erbach-Schoenberg E, Tatem AJ, Wetter E, Lu X, et al. Population mobility reductions associated with travel restrictions during the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone: Use of mobile phone data. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(5):1562–70 Available from: http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/.

Ganesan M, Prashant S, Mary VP, Janakiraman N, Jhunjhunwala A, Waidyanatha N. The use of mobile phone as a tool for capturing patient data in southern rural Tamil Nadu, India. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2011;5(2):219–27 Available from: http://jhidc.org/index.php/jhidc/article/view/64.

Mutreja A, DongWook K, Thomson NR, Connor TR, JeHee L, Kariuki S, et al. Evidence for several waves of global transmission in the seventh cholera pandemic. Nature. 2011;477(7365):462–5. Available from: http://www.nature.com/nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10392.

Gulenkin VM, Korennoy FI, Karaulov AK, Dudnikov SA. Cartographical analysis of African swine fever outbreaks in the territory of the Russian Federation and computer modeling of the basic reproduction ratio. Ward M, Perez A. Prev Vet Med. 2011;102(3):167–174. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/01675877

Veerasekar G, Swaminathan K. Dengue outbreak 2012: geo mapping and snapshot of clinical course from a tertiary referral center in South India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2016;64(October):38–42 Available from: http://www.japi.org/october_2016/06_oa_dengue_outbreak_2012_geo.pdf.

Tom-Aba D, Olaleye A, Olayinka AT, Nguku P, Waziri N, Adewuyi P, et al. Innovative technological approach to Ebola Virus Disease outbreak response in Nigeria using the open data kit and form hub technology. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131000 Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0131000.

Sesay T, Denisiuk O, Shringarpure KK, Wurie BS, George P, Sesay MI, , Zachariah R, et al. Paediatric care in relation to the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak and general reporting of deaths in Sierra Leone. Suppl Oper Res to Support Heal Syst Recover Follow West African Ebola outbreak. 2017;7(Suppl. 1):S34–9. Available from: http://ingentaconnect.com/contentone/iuatld/pha/2017/00000007/A00101s1/art00008, doi: https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.16.0088

Rebaudet S, Mengel MA, Koivogui L, Moore S, Mutreja A, Kande Y, et al. Deciphering the origin of the 2012 cholera epidemic in Guinea by integrating epidemiological and molecular analyses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(6):e2898 Available from: http://www.plosntds.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pntd.0002898.

Sacks JA, Zehe E, Redick C, Bah A, Cowger K, Camara M, et al. Introduction of mobile health tools to support Ebola surveillance and contact tracing in Guinea. Glob Heal Sci Pract. 2015;3(4):646–59. Available from: http://www.ghspjournal.org/content/3/4/646.full. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00207.

Chakkaravarthy VM, Vincent S, Ambrose T. Novel approach of geographic information systems on recent out-breaks of chikungunya in Tamil Nadu, India. J Environ Sci Technol. 2011;4(4):387–94. Available from: http://scialert.net/fulltext/?doi=jest.2011.387.394&org=11. https://doi.org/10.3923/jest.2011.387.394.

de Vera Luz MA, Nabeshima T, Moi ML, MTA D, LAS P, MPS D, et al. An epidemic of dengue virus serotype-4 during the 2015–2017: The emergence of a novel genotype iia of denv-4 in the Philippines. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2019;72(6):413–9 Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31474703/, [cited 2020 Sep 12].

Bashir RSE, Hassan OA. A One Health perspective to identify environmental factors that affect Rift Valley fever transmission in Gezira state, Central Sudan. Trop Med Health. 2019;47(1).

Makke G, Bitar I, Salloum T, Panossian B, Alousi S, Arabaghian H, et al. Whole-genome-sequence-based characterization of extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii hospital outbreak. mSphere. 2020;5(1):e00934 Available from: https://msphere.asm.org/content/msph/5/1/e00934-19.full.pdf.

Show evidence that apps for COVID-19 contact-tracing are secure and effective. Nature. 2020;580:563–7805. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01264-1 Nat Publ Group.

Polonsky JA, Baidjoe A, Kamvar ZN, et al. Outbreak analytics: a developing data science for informing the response to emerging pathogens. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2019;374(1776):20180276. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0276.

WHO. Global Outbreak Alert & Response Network: WHO; 2015.

Dehnavieh R, Haghdoost A, Khosravi A, Hoseinabadi F, Rahimi H, Poursheikhali A, et al. The District Health Information System (DHIS2): A literature review and meta-synthesis of its strengths and operational challenges based on the experiences of 11 countries. Health Inf Manag. 2019;48(2):62–75 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29898604. [cited 2019 Oct 3].

Shuaib FMB, Musa PF, Gashu ST, Onoka C, Ahmed SA, Bagana M, et al. AVADAR (Auto-Visual AFP Detection and Reporting): demonstration of a novel SMS-based smartphone application to improve acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance in Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(Suppl 4):1305 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30541508, [cited 2019 Oct 4].

Acknowledgements

PK would like to thank the team of the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team for their support throughout study development and manuscript preparation.

Funding

The UK Public Health Rapid Support Team is funded by the National Institute for Health Research and Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PK designed the study and developed the search strategy. PK and JM provided feedback on search strategy and study design.PK conducted the systematic literature search. PK reached out to partners for grey literature. PK and JM conducted the review of literature, abstracts and full texts. PK and JM conducted data extraction. PK wrote the manuscript and prepared all tables and figures. PK, JM, KS LM and AS reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. A consent form was included as part of the online questionnaire which explained the objectives of the study and assured the anonymity and confidentiality of participants. Ethics approval was granted by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Ethics committee (reference 17140). Informed consent was obtained from all participants who took part in the online stakeholder survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategies used in Medline, Embase and Global Health, CINAHL and Web of Sciences databases. This file contains three sets of search strategies (1) those used for OVID database – Medline, Embase and Global Health; (2) CINAHL database and (3) Web of Sciences database.

Additional file 2.

Definitions used for data extraction. Table shows terms used for technical characteristics of electronic tools examined and their definitions.

Additional file 3.

Data dictionary of the online Enketo Stakeholder survey on electronic data collection, management and analysis tools. The data dictionary shows the variable names, question text, response options/question type, skip logic and validation information as well as whether a question was required or not.

Additional file 4.

List of studies excluded from the systematic review (2010–2020) and their reasons for exclusion. Dataset that describes the studies excluded from the systematic review (2010–2020) and includes the first author, title, journal and year of publication of the study and the reason for exclusion.

Additional file 5.

Number and percentage of respondents to the stakeholder survey per responding organisation. Table shows the number and percentages of respondents per organisation that responded to the stakeholder survey.

Additional file 6.

List of electronic tools reported by organisations with at least two respondents to the survey. Table shows number of stakeholder survey respondents per organisation (where at least 2 respondents from the same organisation responded) and the data collection, management and analysis tools used per organisation.

Additional file 7.

List of electronic tools identified and their reported uses from the systematic review (2010–2020)/stakeholder survey. Dataset that describes the reported uses of the electronic tools either from the systematic review (2010–2020) and/or from the stakeholder survey. Where no data were found on a particular use of a tool, “don’t know” was entered in the database and where a tool only had one function (data collection or management or analysis), “NA” for not applicable was added to the relevant columns.

Additional file 8.

Technical characteristics of tools as identified from the review, survey, and tool developers’ websites/direct contact. Dataset that describes the technical characteristics of the electronic tools as identified from the systematic review (2010–2020), survey or from review of software websites or contact with software developers. Where no data were found on a particular characteristic of a tool, “don’t know” was entered in the database and where a tool only had one function (data collection or management or analysis), “NA” for not applicable was added to the relevant columns. The Samaritan’s Purse Reporting System was excluded from this database on request from the organisation.

Additional file 9.

PRISMA checklist. PRISMA checklist describes how PRISMA criteria were applied to the conduct of the systematic review.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Keating, P., Murray, J., Schenkel, K. et al. Electronic data collection, management and analysis tools used for outbreak response in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and stakeholder survey. BMC Public Health 21, 1741 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11790-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11790-w