Abstract

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a major public health problem with harmful consequences. In Australia, there is no national standard screening tool and screening practice is variable across states. The objectives of this study were to assess in the antenatal healthcare setting: i) the validity of a new IPV brief screening tool and ii) women’s preference for screening response format, screening frequency and comfort level.

Methods

One thousand sixty-seven antenatal patients in a major metropolitan Victorian hospital in Australia completed a paper-based, self-administered survey. The survey included four screening items about whether they were Afraid/Controlled/Threatened/Slapped or physically hurt (ACTS) by a partner or ex-partner in the last 12 months; and the Composite Abuse Scale (reference standard). The ACTS screen was presented firstly with a binary yes/no response format and then with a five-point ordinal frequency format from ‘never’ (0) to ‘very frequently’ (4). The main outcome measures were test statistics of the four-item ACTS screening tool (sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and area under the curve) against the reference standard and women’s screening preferences.

Results

Twelve-month IPV prevalence varied depending on the ACTS response format with 8% (83) positive on ACTS yes/no format, 12.8% (133) positive on ACTS ordinal frequency format and 10.5% (108) on the reference Composite Abuse Scale. Overall, the ACTS screening tool demonstrated clinical utility for the ordinal frequency format (AUC, 0.80; 95% CI = 0.76 to 0.85) and the binary yes/no format (AUC, 0.74, 95% CI = 0.69 to 0.79). The frequency scale (66%) had greater sensitivity than the yes/no scale (51%). The positive and negative predictive values were 56 and 96% for the frequency scale and 68 and 95% for the yes/no scale. Specificity was high regardless of screening question response options. Half (53%) of the women categorised as abused preferred the yes/no scale. Around half of the women (48%, 472) thought health care providers should ask pregnant women about IPV at every visit.

Conclusions

The four-item ACTS tool (using the frequency scale and a cut-off of one on any item) is recommended for written self-administered screening of women to identify those experiencing IPV to enable first-line response and follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a major public health problem with harmful consequences on the health of women [1], and their unborn babies and children [2, 3]. Globally, it is estimated that about 1 in 3 women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner [4]. IPV is common during pregnancy, with estimates varying from 3 to 29% depending on the measure used, and for many women, violence begins or escalates during pregnancy and the postpartum period [5,6,7]. Women experiencing IPV have higher risk for adverse maternal and perinatal health outcomes including postnatal depression, perceived stress [8]; unintended pregnancies, abortions [9]; low birth weight and preterm births [10].

Given the increased contact with healthcare providers during pregnancy, antenatal care presents a unique opportunity to enquire routinely about IPV [11]. A Cochrane systematic review [12] suggests that IPV screening and initial response by a health professional increases identification with no increase in referrals or changes in women’s experience of violence or wellbeing. However, in antenatal care there may be sufficient evidence to recommend screening all women attending, with two antenatal studies [13, 14] showing improvement in some outcomes for women [12]. Despite increased efforts to reduce IPV and its negative health consequences, it is not consistently screened for in antenatal care across the world [15, 16]. Although there are many barriers to effective identification and response for women experiencing IPV [16], one factor increasing a health professional’s likelihood of screening for IPV is having a set of scripted questions [17,18,19,20]. The use of a validated tool suitable to antenatal settings may facilitate consistent screening but also allow comparisons across health facilities and changes over time for quality improvement purposes [17].

In evaluating IPV screening tools, the balancing act between correctly identifying those experiencing IPV (the true positive rate or sensitivity) and eliminating those not experiencing it (true negative rate specificity) is difficult when dealing with a social problem rather than a biomedical disease with a straight-forward diagnostic gold standard [21]. Thus, there are several analysis issues including that there is no agreed upon gold standard for IPV measurement and pre-test prevalence will alter the positive predictive value of the screening tool. There are also interpretation issues, such as the reductionist approach of IPV screening tools in which women are dichotomised into abused or non-abused categories. Among any group of women who do not report IPV on a particular tool, will be some who have experienced abusive behaviours but do not wish to label themselves as abused. This should be respected and understood.

With IPV it is important to maximise reach to those who have been abused by a partner so that support can be offered, that is, there is a need to maximise the true positive rate. However, there are implications of both false positives (overidentifying cases of IPV) and false-negatives (missing cases of IPV). An ‘over-inclusive’ IPV screen, will mean that some women will be identified as experiencing abuse when the behaviours they experience are not consistent with the current understanding of the coercive controlling dynamics of IPV. For these women (returning a false positive IPV screen), there is a risk of being labelled as someone who is experiencing IPV resulting in unnecessary use of intervention resources. Where the prevalence of the condition of interest is very low, as it often is with screening for IPV in the last 12 months, a test has to be highly specific to reduce the number of false-positive results to an acceptable level [22].

Gaps remain on the most effective ways of screening to identify those affected by IPV and what screening tools to use [23]. A 2009 systematic review showed that the psychometric properties varied across IPV screening tools and settings [24]. This review reported that the most studied screening tools were the Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS, sensitivity 30–100%, specificity 86–99%); the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST, sensitivity 47%, specificity 96%); the Partner Violence Screen (PVS, sensitivity 35–71%, specificity 80–94%); and the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS, sensitivity 93–94%, specificity 55–99%). Internal reliability (HITS, WAST); test–retest reliability (AAS); concurrent validity (HITS, WAST); discriminant validity (WAST); and predictive validity (PVS) were also assessed, however the authors concluded that no single IPV screening tool had well-established psychometric properties. A 2016 systematic review [23] found 10 IPV screening tools and recommended three as having stronger psychometric values, assessing physical, emotional and sexual IPV and having been validated against a reference standard: Women Abuse Screen Tool (WAST), Humiliation, Afraid, Rape and Kick (HARK) and Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS). A strength of the tools is inclusion of questions about fear, which has the potential to identify the majority of women experiencing serious IPV [25].

However, there are several issues with these tools including length, inclusion of sexual violence behaviours, scoring resulting in varied prevalence among pregnant women and lack of addressing coercive control behaviours. The eight item tool WAST [26], though comprehensive, is longer than most tools and this is a consideration in light of findings about the importance of tool brevity e.g., HARK four-item tool [20, 27]. Both tools also include items about sexual violence, which is common in abusive relationships, yet in the context of an initial screen, may be difficult for health providers to ask about and a particularly challenging form of abuse for women to name [28, 29]. The five item AAS has a simple scoring system and has been validated in perinatal settings [30,31,32,33,34,35,36] but has demonstrated a large range of prevalence from 2.8% [34] to 35.5% [35] for IPV during the antenatal period and up to 41% [31] for any history of IPV among a sample of pregnant women. Further, none of these scales (i.e., WAST, HARK, AAS) capture coercive control which is seen as an important part of the pattern of IPV [37].

Systematic reviews have shown that women find screening tools acceptable [38, 39]; however, an additional characteristic of IPV screening tools that is understudied is the format of item responses. Women are generally asked to report the occurrence of abusive behaviours in the past 12 months in either a binary response format (yes or no) or an ordinal frequency format. While HARK [27], AAS [40], and PVS [41] response choices are yes or no, the WAST has three options (‘often’, ‘sometimes’ and ‘never’) [42] and HITS has five options (‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘fairly often’, ‘frequently) [43]. It is not known whether response format affects IPV screening tool validity. It is also not known whether women prefer to respond to screening questions with a binary yes/no or have a range of frequency options. IPV screen length, response options and scoring may all impact on both validity and ease of use for health practitioners and women clients.

Recognising the shortcomings of current IPV screening tools for use in antenatal care, we developed the brief ACTS tool through reviewing items on existing tools and a consensus discussion amongst the authors [17]. In this paper, we introduce the ACTS tool and present our findings of initial tool testing. Our aim was to test in antenatal care i) the accuracy of the new IPV screening tool and ii) how women prefer to be asked about IPV. We present test statistics (sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values and area under the receiver operating curve [AUC]) against the reference standard Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) [44] and the utility of the ACTS tool with two alternative response formats. We also assess women’s preference for IPV screen response format and frequency of asking, along with their comfort level in being screened.

Methods

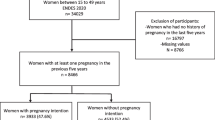

This analysis was part of the larger study - Sustainability of identification and response to domestic violence in antenatal care (the SUSTAIN study), funded by the Australian Research Organisation for Women’s Safety. Detailed methods for the SUSTAIN study are reported elsewhere [17]. Briefly, participants were antenatal patients in a major metropolitan Victorian hospital who completed a paper-based, self-administered survey while they waited for their antenatal clinic appointments.

Data collection and recruitment

Patients were approached in the antenatal waiting room between May and July 2018 and asked if they were accompanied by a partner, family member or other person(s). Those who responded ‘yes’ were thanked and not invited to participate to minimize potential risks to the safety of women from possible perpetrator awareness. Women presenting unaccompanied who were at least 16 years of age and were proficient in written English, Arabic, Mandarin or Cantonese (the four most common languages spoken at the hospital) were offered information about the SUSTAIN study.

The SUSTAIN survey included six sections: pregnancy and pregnancy care; health and well-being; relationships and safety; supports; personal and household details; and views about the survey [17]. Within the relationships and safety section were the IPV screening four items relating to partner or ex-partner behaviours: Afraid, Controlled, Threatened to physically hurt, Hit, Slapped, or physically hurt (ACTS) (see Table 2). These four items were presented twice consecutively within the survey, with two response formats. We advised women that there would be repetition of questions and encouraged them to answer all formats. The first format presented a binary ‘yes’ (coded 1) or ‘no’ (coded 0) response to each of the four items. The second format presented a five-point ordered response based on frequency of the behaviours (never = 0, rarely = 1, sometimes = 2, frequently = 3, very frequently = 4). An additional question asked which of these response formats women preferred when being asked about IPV (Thinking about question 2a and 2b, which way would you prefer to be asked? 2a [answering with yes or no], 2b [answering how often]). Another question asked how often they would prefer to be asked ACTS during pregnancy (When do you think is the best time during pregnancy for health care providers to ask about domestic violence? [at the first visit only; at some visits i.e., first, 28 weeks and 36 weeks; at every visit; I don’t think they should ask]). The SUSTAIN survey then included the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) [44] as an IPV reference standard. The CAS is a comprehensive, multidimensional measure of IPV covering physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. Women self-report their experience of 30 abuse acts in the past 12 months on a six-point frequency scale from ‘never’ (0) to ‘daily’ (5). It has four dimensions: Severe Combined Abuse, Emotional Abuse, Physical Abuse, and Harassment that provide four categories of abuse for an individual woman’s experience of IPV [44].

.Analysis

A ‘yes’ response to one or more of the four binary format ACTS questions was considered a positive screen for IPV. A response of ‘rarely’ or higher for one or more of the four frequency format ACTS questions was considered a positive screen for IPV. For the reference standard CAS, scoring on one or more of the four abuse categories was considered positive for experiencing IPV [17]. A small number of participants were unable to be classified due to missing screening and/or CAS items. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of the ACTS screening tools were assessed against the CAS. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to assess the overall accuracy of the ACTS screening questions using CAS as the reference. For each ROC curve, the AUC is reported when plotting sensitivity against 1-specificity. AUC of greater than 0.75 is generally considered clinically useful [45].

Participants were assured participation was voluntary and choosing not to participate would not impact their care. A distress protocol and information resources were available for both women and researchers involved in the study. Where women screened positive for IPV, they were prompted to speak to their midwife or social worker, or IPV service.

Results

The survey was completed by 1067 pregnancy care patients aged between 18 and 48 years, representing a response rate of 76.2%. Approximately half (49%, 515) of participants were pregnant with their first child and nearly all (97%; 1008) had a current partner. The study sample was linguistically diverse with about 27% (273) of participants having a first language other than English and 1% [10] identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander women. Over 90% (931) had completed at least Year 12 education (Table 1).

Rates of IPV and abusive behaviours experienced by participants

The proportion of women screening positive for IPV was 8% (n = 83) based on the four-item binary (yes/no) response format ACTS and 12.8% (n = 133) for the ordinal frequency response format (Table 2). These rates compare to 10.5% (n = 108) of women categorised as positive for IPV experience using the CAS reference standard. While both ACTS IPV screen prevalence estimates approximated the referent standard (overlapping confidence intervals), the estimated prevalence of the dichotomous response format tool was lower than for the frequency response format.

Accuracy of ACTS IPV screen

The test performance of the four individual ACTS screen items and the overall screen, judged against the referent CAS, by response format, followed a consistent pattern (see Table 3). The sensitivity was higher with the ordinal frequency response format while the specificity was higher for the binary response format. Given the more stringent binary response (resulting in fewer women categorised as abused) compared to the ordinal frequency format, it is not surprising that the positive predictive value was higher for the binary format (0.68) compared to the ordinal (0.56). This is due to the yes/no response format being associated with fewer false positives. Each of the ACTS’ four items and overall, regardless of response format, performed well in identifying women who did not experience IPV based on the CAS, with negative predictive values of .95 (binary response) and .96 (ordinal frequency response).

The ACTS screening tool demonstrated good overall accuracy demonstrated by an area under the ROC curve of 0.80 (95% CI = 0.76 to 0.85) for the ordinal frequency response and 0.74, (95% CI = 0.69 to 0.79) for the binary response (see Table 3 and Additional file Figure 1).

Women’s preferences for IPV screening response format, frequency of enquiry and comfort to be asked

A small majority (60%) of participants indicated a preference for the ACTS screening tool option with the binary yes/no response format over the ordinal frequency format (Table 4). Comparing those women exposed to IPV or not, 53% of women who have experienced IPV (53, 95% CI = .43, .62) preferred the binary yes/no response format compared to 61% (489, 95% CI = 0.58, 0.62) of women not experiencing IPV.

The majority of participants (82%) supported health care providers asking about IPV screening more than once (‘at some visits’ or ‘at every visit’) during antenatal care, compared to at only the first visit (14%), or not at all (3%) (Table 4). While most women were comfortable talking about IPV, one out of every three women (31%) exposed to IPV (CAS positive) indicated they were uncomfortable or very uncomfortable talking with health providers about experiencing fear of a current or ex-partner (Table 4).

Discussion

This study assessed the validity of a new four-item ACTS IPV screening tool developed for use in antenatal healthcare settings and the findings are promising. In this sample of 1067 women, the ACTS screening tool with an ordinal frequency response format, provided a balance of sensitivity and specificity, correctly identifying 66% of women with IPV and 94% of women without IPV. The ACTS screening tool also demonstrated clinical utility, with 56% of women with a positive screen and 96% of women with a negative screen correctly classified based on the referent Composite Abuse Scale (predictive values). These predictive values are dependent on the pre-test prevalence, which in this sample was around 1 in 10 women attending the antenatal care setting. Similar trends were observed for the binary response format (51% sensitivity and 97% specificity with 68% of true IPV-positive cases and 95% of true IPV-negative cases). These figures are higher than with other tools including the WAST (sensitivity 47%, specificity 96%) and PVS (sensitivity 35–71%, specificity 80–94%) [24].

The ACTS screening tool was efficient at ruling out women who were not experiencing IPV but less accurate for detecting women experiencing IPV. Decisions regarding optimal use of the tool in healthcare settings should be informed by the general objectives of screening. In fact, the high NPV offers clinicians the confidence that women who are not experiencing IPV are more likely to be ruled out during screening than those experiencing IPV. This is a strength of the tool, as it enables clinicians to differentiate between these two groups of women and may allow them to direct more attention and resources through further assessment and follow-up to those who screened positive.

With respect to how screening questions should be framed or asked at antenatal visits, participants categorised as abused were split on which format of response they preferred, while more participants in the non-abused category preferred the binary format. This may be partly attributable to the fact that women in the non-abused category might find yes/ no questions less demanding. On the other hand, women who experience abuse may appreciate being able to disclose in steps, for example, replying “sometimes” rather than committing to the ‘all or nothing’ approach that yes or no requires. This is consistent with the conclusion of an analysis of women’s perspectives on IPV screening questions showing that answers to questions were rarely “yes” or “no” and thus midwives were often unclear whether women’s responses constituted IPV [46]. With regard to frequency of assessing for IPV, over three quarters of women indicated that screening questions should be asked more than once throughout the antenatal period (including 48% of respondents who preferred being asked at every visit). This is consistent with the knowledge that for IPV screening tools to be effective, they need to be repeated during the antenatal period and postnatally, with an ability to document clearly previous answers so women are not repeatedly asked for the same information [47]. Indeed, screening metrics aside, it is vital that screening tools do not dominate decision making but rather complement professional judgement of trained clinicians who are supported by their workplaces [48]. Addressing the sensitive topic of IPV requires trained clinicians knowledgeable about dynamics of IPV, structural entrapment, impacts on families and available specialist resources.

Strengths and limitations

This study included more than 1,000 pregnant women, providing the opportunity for robust analysis of the ACTS tool. There are, however, study limitations to consider. While the sample was large and somewhat diverse, the majority of women in this urban setting were well-educated and financially secure. It is important that policy addressing the health response to IPV address the needs of those experiencing IPV along with a multitude of structural social and economic disadvantages. While we were able to consider women’s preferences for response formats by abuse status, there are likely subgroups of women who require bespoke IPV assessment and response with associated training tailored to women’s backgrounds and context. Research drawing on traditional ways of knowing would be needed to explore a safe and effective assessment and response for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women [49]. In addition, for safety reasons, only women presenting to their antenatal care visit unaccompanied were eligible to participate, which may have excluded some groups of women. The IPV prevalence estimates, therefore, may not be representative of the general antenatal population. In addition, in the SUSTAIN survey, the binary response ACTS tool preceded the tool with ordinal frequency (static order rather than randomised), which was then followed by the Composite Abuse Scale. While women were informed that they would be presented questions in several different ways, the results may be influenced by a testing effect. Finally, further research would be warranted testing the ACTS tool across clinical settings with diverse samples and using different modes of delivery (verbal, written, electronic). Improving the sensitivity of the tool may require such research, including the use of qualitative methods to understand how women interpret the questions and response formats.

Conclusions

We conclude that the ACTS tool provides a new clinically useful resource to identify women in the antenatal setting most likely to be experiencing IPV, who could potentially benefit from a health system response [11]. The introduction of this new brief IPV screening tool, that includes controlling behaviour, offers the opportunity for antenatal clinicians to address this important determinant of health [17]. However, evidence informed practice requires that clinicians are supported by a health system that offers private spaces, mandatory staff training, clear protocols and referral pathways, and leadership [1]. Policies need to encompass all aspects of this health system support.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AAS:

-

Abuse Assessment Screen

- ACTS:

-

Afraid/Controlled/Threatened/ Slapped or physically hurt

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CAS:

-

Composite Abuse Scale

- HARK:

-

Humiliation, Afraid, Rape and Kick

- HITS:

-

Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- PVS:

-

Partner Violence Screen

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SUSTAIN:

-

Sustainability of identification and response to domestic violence in antenatal care

- WAST:

-

Woman Abuse Screening Tool

References

Garcia-Moreno C, Hegarty K, d’Oliveira A, Koziol-McLain J, Colombini M, Feder G. The health-systems response to violence against women. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1567–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7.

Martin-de-las-Heras S, Velasco C, Luna-del-Castillo JD, Khan KS. Maternal outcomes associated to psychological and physical intimate partner violence during pregnancy: A cohort study and multivariate analysis. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(6):e0218255.

Murray AL, Kaiser D, Valdebenito S, Hughes C, Baban A, Fernando AD, et al. The intergenerational effects of intimate partner violence in pregnancy: mediating pathways and implications for prevention. Trauma Viol Abuse. 2020;21(5):964–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018813563.

WHO. Global and regional estimates of violence against women; Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: WHO; 2013.

Phillips J, Vandenbroek P. Domestic, family and sexual violence in Australia: an overview of the issues: Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliamentary Library; 2014.

Gazmararian JA, Lazorick S, Spitz AM. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA. 1996;275(24):1915–20. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1996.03530480057041.

Gartland D, Hemphill SA, Hegarty K, Brown S. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and the first year postpartum in an Australian pregnancy cohort study. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(5):570–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0638-z.

Velonis AJ, O'Campo P, Kaufman-Shriqui V, Kenny K, Schafer P, Vance M, et al. The impact of prenatal and postpartum partner violence on maternal mental health: results from the community child health network multisite study. J Women's Health. 2017;26(10):1053–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.6129.

Pallitto CC, García-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Heise L, Ellsberg M, Watts C, et al. Intimate partner violence, abortion, and unintended pregnancy: results from the WHO multi-country study on Women's health and domestic violence. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2013;120(1):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.07.003.

Hill A, Pallitto C, McCleary-Sills J, Garcia-Moreno C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intimate partner violence during pregnancy and selected birth outcomes. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2016;133(3):269–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.10.023.

WHO. Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines: World Health Organization; 2013.

O'Doherty L, Hegarty K, Ramsay J, Davidson L, Feder G, Taft A. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healtcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD007007.

Kiely M, El-Mohandes A, El-Khorazaty M, Blake S, Gantz M. An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 Pt 1):273–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd482.

Tiwari A, Leung W, Leung T, Humphreys J, Parker B, Ho P. A randomised controlled trial of empowerment training for Chinese abused pregnant women in Hong Kong. BJOG. 2005;112(9):1249–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00709.x.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Screening for domestic violence during pregnancy: options for future reporting in the National Data Collection. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2015.

Sprague S, Madden K, Simunovic N, Godin K, Pham NK, Bhandari M, et al. Barriers to screening for intimate partner violence. Women Health. 2012;52(6):587–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2012.690840.

Hegarty K, Spangaro J, Koziol-McLain J, Walsh J, Lee A, Kyei-Onanjiri M, et al. Sustainability of identification and response to domestic violence in antenatal care: The SUSTAIN Study. 2020.

Department of Health. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pregnancy Care. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2018.

Spangaro J. What is the role of health systems in responding to domestic violence? An evidence review. Aust Health Rev. 2017;41(6):639–45. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH16155.

Spangaro J, Poulos R, Zwi A. Pandora doesn’t live here any more: normalization of screening for intimate partner violence in Australian antenatal, mental health and substance abuse services. Violence Vict. 2011;26(1):130–44. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.26.1.130.

Trevethan R. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values: foundations, pliabilities, and pitfalls in research and practice. Front Public Health. 2017;5:307. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00307.

Power M, Fell G, Wright M. Principles for high-quality, high-value testing. Evid Based Med. 2013;18(1):5–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2012-100645.

Arkins B, Begley C, Higgins A. Measures for screening for intimate partner violence: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Mental Health Nurs. 2016;23(3/4):217–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12289.

Rabin R, Jennings J, Campbell J, Bair-Merritt M. Intimate partner violence screening tools: A systematic review. Am J Prevent Med. 2009;36(5):439–45.

Signorelli M, Taft A, Gartland D, Hooker L, McKee C, MacMillan H, et al. How valid is the question of fear of a partner in identifying intimate partner abuse? A cross-sectional analysis of four studies. J Interperson Viol. 2020:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520934439.

Wathen N, Jamieson E, Macmillan H. Who is identified by screening for intimate partner violence? Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(6):423–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.003.

Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder G. The sensitivity and specificity of four questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accuracy study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8(49):1–9.

Spangaro J, Koziol-McLain J, Zwi A, Rutherford A, Frail M, Ruane J. Deciding to tell: qualitative configurational analysis of decisions to disclose experience of intimate partner violence in antenatal care. Soc Sci Med. 2016;154:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.032.

Bagwell-Gray M, Messing J, Baldwin-White A. Intimate partner sexual violence: a review of terms, definitions, and prevalence. Trauma Viol Abuse. 2015;16(3):316–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014557290.

McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy: severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA. 1992;267(23):3176–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03480230068030.

Norton LB, Peipert JF, Zierler S, Lima B, Hume L. Battering in pregnancy: an assessment of two screening methods. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(3):321–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-7844(94)00429-H.

Anderson BA, Marshak HH, Hebbeler DL. Identifying intimate partner violence at entry to prenatal care: clustering routine clinical information. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002;47(5):353–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1526-9523(02)00273-8.

Keeling J, Mason T. Postnatal disclosure of domestic violence: comparison with disclosure in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(1–2):103–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03486.x.

Lutgendorf M, Thagard A, Rockswold P, Busch J, Magann E. Domestic violence screening of obstetric triage patients in a military population. J Perinatol. 2012;32(10):763–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2011.188.

Gashaw BT, Magnus JH, Schei B. Intimate partner violence and late entry into antenatal care in Ethiopia. Women Birth. 2019;32(6):e530–e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.12.008.

Reichenheim ME, Moraes CL. Comparison between the abuse assessment screen and the revised conflict tactics scales for measuring physical violence during pregnancy. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(6):523–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.011742.

Hamberger LK, Larsen SE, Lehrner A. Coercive control in intimate partner violence. Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;37:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.08.003.

Anderson EJ, Krause KC, Meyer Krause C, Welter A, McClelland DJ, Garcia DO, et al. Web-based and mHealth interventions for intimate partner violence victimization prevention: a systematic review. Trauma Viol Abuse. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019888889.

Todahl J, Walters E. Universal screening for intimate partner violence: a systematic review. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011;37(3):355–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00179.x.

Parker B, McFarlane J. Identifying and helping battered pregnant women. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1991;16(3):161–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005721-199105000-00013.

Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Lowenstein SR, Abbott JT. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277(17):1357–61. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540410035027.

MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, Boyle M, McNutt L-A, Worster A, et al. Approaches to screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296(5):530–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.5.530.

Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li X-Q, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508–12.

Hegarty K, Bush R, Sheehan M. The composite abuse scale: further development and assessment of reliability and validity of a multidimensional partner abuse measure in clinical settings. Violence Vict. 2005;20(5):529–47. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.2005.20.5.529.

Fan J, Upadhye S, Worster A. Understanding receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Can J Emerg Med. 2006;8(1):19–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1481803500013336.

Spangaro J, Koziol-McLain J, Rutherford A, Zwi A. Is it yes?: making sense of responses to routine screening for domestic violence. Psychol Violence. 2011;1:150 in press.

Deshpande NA, Lewis-O’Connor A. Screening for intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2013;6(3–4):141–8.

Trevethan R. Screening, sensitivity, specificity, and so forth: a second, somewhat skeptical, sequel. Modern Health Sci. 2019;2(1):60.

Fiolet R, Tarzia L, Hameed M, Hegarty K. Indigenous peoples’ help-seeking behaviors for family violence: a scoping review. Trauma Viol Abuse. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019852638.

National Health Medical Research Council. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2007.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge contributions made by all the women who so generously participated in this study by sharing their experiences with us. We appreciate contributions made by Jacqueline Kuruppu, Rhiannon McArthur, India Jones, Tanya Hoad and Karyn Smith who assisted with survey data collection at the Victorian study sites.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding provided by Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KH designed and led the study conduct and analyses and wrote the first draft with MKO. JKM and JS contributed to design and analyses and write up of paper. JV undertook data analyses and wrote the results section. JW and JC assisted with the design, conduct and analyses of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was provided by The Royal Women’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference: Project 17/35). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was guided by the National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines, as updated in 2018 [50]. All the study methods were performed in accordance with relevant regulations and guidelines as approved by the Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure 1.

Receiver Operating Characteristic curves for the ACTS screening tool (binary “Yes/No” and Likert-scale “Frequency” formats). Description of data: Receiver Operating Characteristic curves for the ACTS screening tool when presented as binary “Yes/No” format and Likert-scale “Frequency” format

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hegarty, K., Spangaro, J., Kyei-Onanjiri, M. et al. Validity of the ACTS intimate partner violence screen in antenatal care: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 21, 1733 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11781-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11781-x