Abstract

Background

Preterm birth is a risk factor for child survival in both the short and long term. In Zimbabwe, the prevalence of preterm birth is rising, and there are growing concerns about the adverse consequences. This study explored the association between intimate partner violence (IPV) during pregnancy and preterm birth in Zimbabwe.

Methods

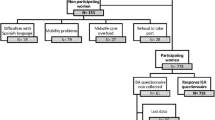

Using data from the 2015 Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey, we applied propensity score matching to estimate the effect of IPV during pregnancy on preterm birth among women of reproductive age (15–49 years). A total of 4833 pregnant women who gave birth during the five years preceding the survey were analysed.

Results

We successfully matched 79 women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy to 372 unexposed during pregnancy. Using the matched sample, the probability of preterm delivery was significantly higher among women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy than those who were not exposed. The findings showed that 7 out of 79 (8.9%) of women exposed to IPV during pregnancy experienced preterm delivery, and 11 out of 372 (3.0%) of those who were not exposed to IPV during pregnancy experienced preterm delivery. In the urban areas, those exposed to IPV during pregnancy were almost five times more likely to experience preterm delivery (OR = 4.8, 95% CI 2.0–11.6), but the association was not significantly different among women in rural areas.

Conclusion

The findings showed that women exposed to IPV during pregnancy were at increased risk of preterm birth. Some of the risk factors associated with IPV were urban residence, low economic status and unemployment. Effective policies and programmes are required to address the issue of IPV in Zimbabwe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infant and child mortality are growing health issues globally, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa [1,2,3]. The complications from preterm birth, including sepsis, periventricular leukomalacia, seizures, infections, feeding difficulties, cerebral palsy, visual and hearing problems and necrotising enterocolitis [1] have led to approximately 16% of all deaths and 35% of deaths of newborn babies globally [1]. Although there have been policies and intervention programmes to tackle and reduce the issue of both preterm birth [4, 5] and infant mortality in many countries [5,6,7], the desired outcomes have not been achieved [1, 6]. To implement effective interventions, there is the need to understand the factors associated with preterm birth. Reducing and mitigating its adverse consequences is also crucial for achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3, which aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages [7].

The issue of intimate partner violence (IPV) is also a worldwide public health and human rights concern [8,9,10], and it is a risk factor for several mental and physical health outcomes, including STI/HIV infections, unintended pregnancies, injuries and abortion [11,12,13]. IPV is pervasive globally [14,15,16], and it comes in the form of sexual, psychological or emotional aggression [9, 13], usually perpetrated by male partners against female partners [9]. Globally, approximately 35% of all women have experienced domestic violence either by their partners or third parties. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), about three out of every ten women in a relationship had ever experienced domestic violence [14].

Evidence suggests that IPV is one of the most prevalent forms of gender-based violence during or before pregnancy [10], which may have both short and long term adverse consequences for babies and mothers [15]. Experiences of IPV during pregnancy may increase women vulnerability to ill health [12]. The various forms of IPV, such as physical, psychological, sexual, or emotional abuse, have also been shown to have an indirect adverse effect on foetal health outcomes, including low birth weight [16,17,18]. For example, a recent study in Ethiopia found an increased risk of preterm birth and low birth weight among pregnant women who experienced multiple forms of IPV [19]. Several risk factors, including younger age, alcohol abuse, past exposure to violence (childhood sexual abuse), marital status and poverty, have been shown to be associated with IPV during pregnancy [20, 21].

A recent study carried out in sixty three low-and middle-income countries also found a negative association between increased acceptability of IPV against women and antenatal care service utilization among women, but there were variations across regions and countries [22,23,24,25,26,27]. Delay in seeking timely antenatal care has also been associated with IPV during pregnancy [28].

An association between antenatal care service utilization and preterm birth has been found in prior studies [29,30,31,32]. Other previous studies suggest that antenatal care service utilization may be useful only in identifying high-risk women but can also facilitate timely intervention [29, 33]. The risk of preterm birth has also been shown to be higher among pregnant women who start antenatal care late than those who start early [34, 35]. Meanwhile, other factors identified to be associated with preterm birth are vaginal bleeding, hypertensive disorder, smoking and stress [36, 37].

Maternal and child mortality is high in sub-Saharan Africa [38, 39], with Zimbabwe having one of the highest rates of maternal health challenges in the region [17]. While the average sub-Saharan rate of maternal mortality was 500/100000 in 2010, Zimbabwe recorded an average of 570/100000 live births [17]. In a recent study in Zimbabwe, Shamu et al. (2018) found intimate partner violence and forced first sex to be associated with adverse health consequences for unborn babies and mothers.

Despite the substantial evidence that IPV during pregnancy impacts negatively on both mother and child health [17], no study has explored the relationship between IPV and preterm birth in Zimbabwe. Hence, this study investigated the relationship between IPV during pregnancy and preterm birth in Zimbabwe. The following research questions will be addressed. (i) Is intimate partner in pregnancy associated with preterm birth in Zimbabwe? (ii) What are the risk factors associated with preterm birth and IPV exposure in Zimbabwe?

Methods

Data sources

The data for the analysis was from the latest (2015) Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey (ZDHS). The survey was undertaken by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency in collaboration with other international organisations, and it is nationally representative of men and women in their reproductive age (15–49 years). In the survey, samples of households were drawn using a stratified multistage cluster sampling design. The standard woman’s questionnaire was used to obtain information on women’s background, reproductive and birth history, information about family planning, maternity history, child immunization, child health and nutrition, marriage and sexual activity, fertility preferences, husband’s background and HIV/AIDS related knowledge and behaviours and other health issues. For this study, we limited our sample to women who gave birth in the five years preceding the survey (N = 4833).

Outcome measure

The outcome variable for this study was preterm birth. Preterm birth was defined as babies born alive before 37 weeks of completed pregnancy or the last babies the respondents had prior to 37 completed weeks of gestation (approximately less than 8 months). On the other hand, term birth was defined as babies born alive after 37 weeks of completed pregnancy or last babies born alive after 37 completed weeks of gestation (9 months or older).

Independent variable

Intimate partner violence (IPV) was the independent variable of interest. This variable was a combination of at least one type of intimate partner abuse experienced by a woman (i.e., physical, sexual or emotional). In the survey, women were asked a series of questions about whether they were exposed to any of the aforementioned forms of violence. The questions posed were for example, “did your husband/partner ever: slap, push, shake, punch, beat, kick or try to strangle you, throw something on you, threaten you using a harmful object?” These questions were used to derive physical violence. Sexual violence was assessed by the questions “did your husband/partner ever physically force you to have sexual intercourse even when you did not want? Or force you with threats to perform any sexual acts you did not want?” Psychological violence was assessed using questions such as “did your husband/partner humiliate you in front of others, threaten to hurt you or those close to you with harm?” Response categories were: ‘yes’ (coded as 1) or ‘no’ (coded as 0).

Covariates

Covariates included in the analysis were maternal age, educational level, residence, wealth index, work status, age at first intercourse, partner’s level of education, prenatal care, number of prenatal care visits and cigarette smoking.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, propensity score matching and subgroup risk analysis were performed in this study. We used descriptive statistics to show the distribution of respondents by the key variables. Values were expressed as absolute numbers (percentages) and mean (standard deviation) for categorical and continuous variables respectively. All cases in the DHS data were given weights to adjust for differences in probability of selection and to adjust for non-response in order to produce the proper representation. Individual weights were used for descriptive statistics.

For propensity score analysis, we first examined the baseline characteristics of the respondents and estimated standardised differences for all variables before and after matching. A standardised difference of 10% or more is suggestive of imbalance. We used propensity score methods to account for all measured differences in baseline characteristics between respondents that reported exposure to IPV during pregnancy and those without. The exposed group consisted of women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy and the unexposed group consisted of those who did not experienced violence during pregnancy. The propensity score for this analysis was estimated using logistic regression. We then matched each respondent with IPV with the closest propensity score on a ratio of 1:5 using a nearest neighbour algorithm with no replacement. Furthermore, we calculated the difference in probability of preterm delivery with and without exposure to IPV during pregnancy in the propensity score–matched cohort.

Finally, we examined the risk by different subgroups, i.e. we calculated odds ratio for the association between exposure to IPV during pregnancy and preterm delivery by socioeconomic status. An odds ratio greater than 1 suggests that preterm delivery is more prevalent among those exposed to IPV. Conversely, a value less than 1 indicates that suggests that preterm delivery is less prevalent among those exposed to IPV.

The null hypothesis was tested against a two-sided alternative hypothesis at a significance level of 5%. The data was analysed using Stata version 16 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. Overall, a total of 4833 women gave birth in the five years preceding the survey. Approximately 2.7% and 97.3% of women reported preterm births and term births, respectively. The results further showed that about 3.1% of women reported having ever experienced IPV during pregnancy, while most women (96.9%) did not report any experience of IPV during pregnancy. More than one-fourth of the respondents were within the younger age groups. For instance, 25.5% of the women were in the 25–29 years age group. Most women (70.6%) reported having secondary or higher education. The distribution of husbands’ educational attainment followed a similar pattern, where about 78.6% reported having higher education. Regarding economic status, about 52.2% of the respondents indicated they were working, and 36.2% reported to be in the poor household category. More than two-thirds (60.9%) lived in rural areas. A significant number of women (41.0%) had their first intercourse within the age group of 15–17 years. While nearly all (94.5%) of the respondents registered for prenatal care services, about 40.2% attended 0–4 times of antenatal care.

Effect of IPV exposure during pregnancy on preterm delivery

The characteristics of the respondents before and after matching are shown in Table 2. There were important baseline differences between respondents with exposure to IPV during pregnancy and those not exposed. Women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy tended to be middle-aged adults compared those who were not exposed. Those exposed to IPV were more likely to be from richer wealth index category, rural areas and less likely to have attended antenatal care. We successfully matched 79 respondents exposed to IPV during pregnancy to 372 not exposed to IPV during pregnancy. After matching, absolute standardised differences were less than 10% for most of the variables used for the propensity score matching, suggesting an adequate match (Table 2). Using the matched sample, the probability of preterm delivery was significantly higher among women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy than those who were not exposed (8.86% vs 2.96%, p = 0.015). 7 out of 79 (8.86%) of women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy reported preterm delivery, while 11 out of 372 (2.96%) of those who were not exposed to IPV during pregnancy experienced preterm delivery.

Risk by different subgroups

Figure 1 shows the association between exposure to IPV during pregnancy and preterm delivery by socioeconomic status. In the urban areas, the results revealed that women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy were almost five times more likely to experience preterm delivery (OR = 4.79, 95% CI 1.98–11.56), but the association was not significantly different among women in rural areas. Similarly, the association was significant among women from poorer household, lower education and those who were not working.

Discussion

Preterm birth is one of the leading causes of complications and death globally among children under 5 years [1, 40]. Approximately 15 million babies are born before completed weeks of gestation (preterm), and the number is on the rise [41, 42]. Prior evidence from WHO estimates from 184 countries with reliable data across the world put the prevalence of preterm birth at 5–18% [42, 43], but there are also country and regional variations [44, 45]. African and Asian countries have the highest rates [46], where more than 60% of preterm births occur in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In sub-Saharan Africa, Zimbabwe has one of the highest prevalence (16.6%) [47].

The prevalence of both IPV [48, 49] and preterm birth [50] are high in Zimbabwe. This study therefore explored the association between intimate partner violence during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth in Zimbabwe, using DHS data collected in 2015. The analyses involved 4833 women who gave birth during the five years preceding the survey. IPV during pregnancy was the exposure and preterm delivery was the outcome of interest. Overall, 3.1% of women reported having ever experienced IPV during pregnancy; with similar prevalence for preterm births.

We applied propensity score matching to estimate the effect of IPV during pregnancy on preterm birth among women, and successfully matched 79 respondents exposed to IPV during pregnancy to 372 not exposed to IPV during pregnancy. Regarding the characteristics of respondents before and after matching, we found disparities among women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy and those not exposed. For instance, the findings showed a pattern where women in the middle-aged groups were more likely to be exposed to IPV during pregnancy than older women. This finding is consistent with a recent meta-analyses [51] and previous cross-sectional studies [52, 53]. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that younger and middle-aged women are more likely to depend on their partners than older women [54, 55], which limits their autonomy in unions [56], leading to excessive control and abuse from their partners.

Consistent with prior studies [9, 57], we found that women who had experienced IPV during pregnancy were more likely to live in rural areas [58, 59], and they had inadequate antenatal visits [9, 57]. These findings may be linked with social norms and traditional belief, particularly in rural areas, where women justify male dominance and abusive acts [60]. Another associated risk factor could be poor socioeconomic conditions including low education and poverty among women in rural areas [58, 59]. Poverty has been shown to be associated with IPV [61, 62], as women who face financial constraints may heavily depend on their partners [63]; and may be at risk of being abused [64]. By contrast, our study showed that rich women were more likely to be exposed to IPV [65]. While this finding is consistent with some previous studies [66], other studies found that improved financial status may be a protective factor against IPV [62, 64, 67]. Nonetheless, we speculate that economically empowered women may also risk being abuse by their male partners who feel threatened by their wealth [68].

The findings revealed more preterm delivery among women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy compared to those who were not exposed, consistent with prior findings [9, 10, 19, 69, 70]. Nonetheless, a study conducted by Audi et al. (2008) did not find any significant association between domestic violence during pregnancy and prematurity [71]. Our findings further revealed a higher incidence of preterm birth among women who were exposed to IPV during pregnancy in urban areas compared to their counterparts in the rural areas. Women in urban areas were about five times more likely to experience preterm birth during pregnancy. Stress and anxiety of urban life, depression, career and tendency of urban women to marry late are some of the factors that have been implicated to explain this phenomenon [10, 72, 73].

Limitations and strength

Our study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of this study prevents conclusions that do not permit fortitude of causality between preterm birth and other variables. Second, self-report information by respondents could be affected by recall bias, for instance, errors may occur in reporting of age of respondents at marriage due to undocumented registration of age system Third, the use of propensity score matching does not eliminate or overcome the initial bias in selection [74]. Despite these limitations, this study used nationally representative DHS data, where selected participants were sampled using probability sampling methods. Also, propensity score matching contributes more to precise estimation of treatment response and balances observed baseline covariates between treatment groups [75].

Conclusion

The findings indicate that exposure to intimate partner violence during pregnancy increased the risk of preterm birth in Zimbabwe. Some of the risk factors associated with IPV were urban residence, low economic status and unemployment. Thus, effective policies and programmes that target women empowerment, education and development are needed to tackle the issue of IPV against women and preterm birth.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study were sourced from Demographic and Health surveys (DHS) and available here: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Abbreviations

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Surveys

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller A-B, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019 Jan;7(1):e37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0.

Budu E, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Seidu AA, Zegeye B, Yaya S. Does birth interval matter in under-five mortality? Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys from Eight Countries in West Africa. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:5516257–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5516257. eCollection 2021.

Idriss-Wheeler D, Yaya S. Exploring antenatal care utilization and intimate partner violence in Benin - are lives at stake? BMC Public Health. 2021 Apr 30;21(1):830. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10884-9.

He Z, Bishwajit G, Yaya S, Cheng Z, Zou D, Zhou Y. Prevalence of low birth weight and its association with maternal body weight status in selected countries in Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018 Aug 29;8(8):e020410. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020410.

Requejo J, Merialdi M, Althabe F, Keller M, Katz J, Menon R. Born too soon: care during pregnancy and childbirth to reduce preterm deliveries and improve health outcomes of the preterm baby. Reprod Health. 2013;10(1):S4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S4.

Pinzón-Rondón ÁM, Gutiérrez-Pinzon V, Madriñan-Navia H, Amin J, Aguilera-Otalvaro P, Hoyos-Martínez A. Low birth weight and prenatal care in Colombia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015 Dec;15(1):118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0541-0.

Loewe M, Rippin N. The Sustainable Development Goals of the Post-2015 Agenda: Comments on the OWG and SDSN Proposals. SSRN Journal [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Sep 30]; Available from: http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=2567302

Yaya S, Gunawardena N, Bishwajit G. Association between intimate partner violence and utilization of facility delivery services in Nigeria: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019 Aug 17;19(1):1131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7470-1.

Jaraba SMR, Garcés-Palacio IC. Association between violence during pregnancy and preterm birth and low birth weight in Colombia: analysis of the demographic and health survey. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(11):1149–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2019.1566331.

Sigalla GN, Mushi D, Meyrowitsch DW, Manongi R, Rogathi JJ, Gammeltoft T, et al. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and its association with preterm birth and low birth weight in Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0172540. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172540.

Gill M, Haardörfer R, Windle M, Berg CJ. Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence and Relationships to Sexual Risk-Related Behaviors Among College Students. The Open Public Health Journal [Internet]. 2020;13(1):559–68. [cited 2021 Jun 5]. Available from: https://benthamopen.com/FULLTEXT/TOPHJ-13-559/

Bazargan-Hejazi S, Kim E, Lin J, Ahmadi A, Khamesi MT, Teruya S. Risk factors associated with different types of intimate partner violence (IPV): an emergency department study. J Emerg Med. 2014;47(6):710–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.07.036.

Plichta SB. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: policy and practice implications. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19(11):1296–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504269685.

WHO. WHO | Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. [Internet]. WHO. 2013 [cited 2020 Feb 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/

Hill A, Pallitto C, McCleary-Sills J, Garcia-Moreno C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intimate partner violence during pregnancy and selected birth outcomes. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Jun;133(3):269–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.10.023.

Navvabi-Rigi SD, Moudi Z, Sheikhi ZP, Moudi F. The association between Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) during pregnancy and birth weight. Prensa Medica Argentina. 2018;104(3).

Shamu S, Munjanja S, Zarowsky C, Shamu P, Temmerman M, Abrahams N. Intimate partner violence, forced first sex and adverse pregnancy outcomes in a sample of Zimbabwean women accessing maternal and child health care. BMC Public Health. 2018 Dec;18(1):595. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5464-z.

Dhar D, McDougal L, Hay K, Atmavilas Y, Silverman J, Triplett D, et al. Associations between intimate partner violence and reproductive and maternal health outcomes in Bihar, India: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2018 Dec;15(1):109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0551-2.

Berhanie E, Gebregziabher D, Berihu H, Gerezgiher A, Kidane G. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a case-control study. Reprod Health. 2019 Feb 25;16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0670-4.

Shamu S, Abrahams N, Temmerman M, Musekiwa A, Zarowsky C. A systematic review of African studies on intimate partner violence against pregnant women: prevalence and risk factors. PLoS One. 2011 Mar 8;6(3):e17591. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017591.

Taillieu TL, Brownridge DA. Violence against pregnant women: prevalence, patterns, risk factors, theories, and directions for future research. Aggress Violent Behav. 2010 Jan 1;15(1):14–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.07.013.

Sripad P, Sharif MIH, Charity N, Warren EC. Autonomy, intimate partner violence, and maternal health-seeking behavior: Findings from mixed-methods analysis in Bangladesh. Ending Eclampsia Country Brief. Washington, DC: Population Council; 2019. http://www.endingeclampsia.org/resources/autonomy-intimate-partner-violence-and-maternal-health-seeking-behavior-findings-from-mixed-methods-analysis/

Singh JK, Evans-Lacko S, Acharya D, Kadel R, Gautam S. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and use of antenatal care among rural women in southern Terai of Nepal. Women Birth. 2018 Apr;31(2):96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.07.009.

Das S, Bapat U, Shah More N, Alcock G, Joshi W, Pantvaidya S, et al. Intimate partner violence against women during and after pregnancy: a cross-sectional study in Mumbai slums. BMC Public Health. 2013 Sep 9;13(1):817. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-817.

Koski AD, Stephenson R, Koenig MR. Physical violence by partner during pregnancy and use of prenatal Care in Rural India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(3):245–54.

Goo L, Harlow SD. Intimate partner violence affects skilled attendance at Most recent delivery among women in Kenya. Matern Child Health J. 2012 Jul 1;16(5):1131–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0838-1.

Ononokpono DN, Azfredrick EC. Intimate partner violence and the utilization of maternal health care services in Nigeria. Health Care Women Int. 2014;35(7-9):973–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2014.924939. Epub 2014 Aug 8.

WHO. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jul 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/rhr_11_35/en/.

Pervin J, Rahman SM, Rahman M, Aktar S, Rahman A. Association between antenatal care visit and preterm birth: a cohort study in rural Bangladesh. BMJ Open. 2020 Jul 23;10(7):e036699. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036699.

McLemore MR, Berkowitz RL, Oltman SP, Baer RJ, Franck L, Fuchs J, Karasek DA,Kuppermann M, McKenzie-Sampson S, Melbourne D, Taylor B, Williams S, Rand L, Chambers BD, Scott K, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL. Risk and Protective Factors for Preterm Birth Among Black Women in Oakland, California. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00889-2.

Zhang B, Yang R, Liang S-W, Wang J, Chang JJ, Hu K, et al. Association between prenatal care utilization and risk of preterm birth among Chinese women. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2017 Aug;37(4):605–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11596-017-1779-8.

Blondel B, Dutilh P, Delour M, Uzan S. Poor antenatal care and pregnancy outcome. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1993 Aug;50(3):191–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-2243(93)90200-V.

WHO. Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Beeckman K, Louckx F, Downe S, Putman K. The relationship between antenatal care and preterm birth: the importance of content of care. Eur J Pub Health. 2013 Jun 1;23(3):366–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cks123.

Barros H, Tavares M, Rodrigues T. Role of prenatal care in preterm birth and low birthweight in Portugal. J Public Health. 1996 Sep 1;18(3):321–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024513.

Bloom SL, Yost NP, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Recurrence of preterm birth in singleton and twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Sep;98(3):379–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01466-1.

Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Medically indicated preterm birth: recognizing the importance of the problem. Clin Perinatol. 2008 Mar 1;35(1):53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2007.11.001.

Schlein L. UN: Most Child, Maternal Deaths Occur in Sub-Saharan Africa. Voice of America - English [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.voanews.com/africa/un-most-child-maternal-deaths-occur-sub-saharan-africa.

Alvarez JL, Gil R, Hernández V, Gil A. Factors associated with maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: an ecological study. BMC Public Health. 2009 Dec 14;9(1):462. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-462.

Kirk CM, Uwamungu JC, Wilson K, Hedt-Gauthier BL, Tapela N, Niyigena P, et al. Health, nutrition, and development of children born preterm and low birth weight in rural Rwanda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2017 Nov 15;17(1):191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0946-1.

Ahishakiye A, Abimana MC, Beck K, Miller AC, Betancourt TS, Magge H, et al. Developmental outcomes of preterm and low birth weight toddlers and term peers in Rwanda. Annals of Global Health. 2019 Dec 17;85(1):147. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2629.

Preterm birth [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth

Wagura P, Wasunna A, Laving A, Wamalwa D, Ng’ang’a P. Prevalence and factors associated with preterm birth at kenyatta national hospital. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018 Apr 19;18(1):107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1740-2.

PAHO/WHO. Violence against women affects almost 60% of women in some countries of the Americas [Internet]. Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization. 2018. [cited 2021 Jun 14]. Available from:https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14830:violence-against-women-affects-almost-60-of-women-in-some-countries-of-the-americas&Itemid=1926&lang=en.

Violence against women [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Vogel JP, Chawanpaiboon S, Watananirun K, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Moller A-B, et al. Global, regional and national levels and trends of preterm birth rates for 1990 to 2014: protocol for development of World Health Organization estimates. Reprod Health. 2016 Dec;13(1):76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0193-1.

Musona-Rukweza J, Haruzivishe C, Gidiri MF, Nziramasangae P, Stray-Pedersen B. Preterm Birth: A concept analysis. AJHMR. 2017; Volume 3, Issue 1, December, Page No.13–20.

Shamu S, Abrahams N, Zarowsky C, Shefer T, Temmerman M. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional study of prevalence, predictors and associations with HIV. Tropical Med Int Health. 2013 Jun;18(6):696–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12078.

Devries KM, Kishor S, Johnson H, Stöckl H, Bacchus LJ, Garcia-Moreno C, et al. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries. Reproductive Health Matters. 2010;18(36):158–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36533-5.

Althabe F, Howson CP, Kinney M, Lawn J, World Health Organization. Born too soon: the global action report on preterm birth [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2021 Jun 11]. Available from: http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2012/201204%5Fborntoosoon-report.pdf

James L, Brody D, Hamilton Z. Risk factors for domestic violence during pregnancy: a meta-analytic review. Violence Vict. 2013;28(3):359–80. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00034.

Ibrahim ZM, Sayed Ahmed WA, El-Hamid SA, Hagras AM. Intimate partner violence among Egyptian pregnant women: incidence, risk factors, and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2015;42(2):212–9.

Iman’ishimwe Mukamana J, Machakanja P, Adjei NK. Trends in prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence against women in Zimbabwe, 2005-2015. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2020 Jan 20;20(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-019-0220-8.

Santhya KG, Ram U, Acharya R, Jejeebhoy SJ, Ram F, Singh A. Associations between early marriage and young women’s marital and reproductive health outcomes: evidence from India. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;36(3):132–9. https://doi.org/10.1363/3613210.

Rocca CH, Rathod S, Falle T, Pande RP, Krishnan S. Challenging assumptions about women’s empowerment: social and economic resources and domestic violence among young married women in urban South India. Int J Epidemiol. 2009 Apr;38(2):577–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyn226.

Kidman R. Child marriage and intimate partner violence: a comparative study of 34 countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2017 Apr 1;46(2):662–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw225.

Ojeda G, Ordóñez M, Ochoa LH. Colombia Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 2010. 2011 Feb 1 [cited 2020 Jun 10]; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr246-dhs-final-reports.cfm

Nabaggala MS, Reddy T, Manda S. Effects of rural–urban residence and education on intimate partner violence among women in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of health survey data. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):1–23.

Wang L. Education, Gender, Residence, and Attitude toward Intimate Partner Violence: An Empirical Study. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2020;29(7):808–25.

Benebo FO, Schumann B, Vaezghasemi M. Intimate partner violence against women in Nigeria: a multilevel study investigating the effect of women’s status and community norms. BMC Womens Health [Internet]. 2018 Aug 9 [cited 2021 Jun 11];18. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6085661/

Gillum TL. The intersection of intimate partner violence and poverty in black communities. Aggress Violent Behav. 2019 May 1;46:37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.01.008.

Abramsky T, Lees S, Stöckl H, Harvey S, Kapinga I, Ranganathan M, et al. Women’s income and risk of intimate partner violence: secondary findings from the MAISHA cluster randomised trial in North-Western Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2019 Aug 14;19(1):1108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7454-1.

Modie-Moroka T. Intimate partner violence and poverty in the context of Botswana. J Psychol Afr. 2010 Jan 1;20(2):185–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2010.10820362.

Ahmadabadi Z, Najman JM, Williams GM, Clavarino AM. Income, gender, and forms of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2020 Dec 1;35(23–24):5500–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517719541.

Krishnan S. Gender, caste, and economic inequalities and marital violence in rural South India. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26(1):87–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330490493368.

Bates LM, Schuler SR, Islam F, Islam K. Socioeconomic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30(4):190–9. https://doi.org/10.1363/3019004.

Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark C, Schafer J. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: a multilevel analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(5):297–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00052-1.

Akhter R, Wilson JK, Haque SE, Ahamed N. Like a Caged Bird: The Coping Strategies of Economically Empowered Women Who Are Victims of Intimate Partner Violence in Bangladesh. J Interpers Violence. 2020:886260520978177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520978177. Epub ahead of print.

Alhusen JL, Ray E, Sharps P, Bullock L. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Women's Health. 2015 Jan;24(1):100–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4872.

Nunes MAA, Camey S, Ferri CP, Manzolli P, Manenti CN, Schmidt MI. Violence during pregnancy and newborn outcomes: a cohort study in a disadvantaged population in Brazil. Eur J Pub Health. 2011 Feb;21(1):92–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp241.

Audi CAF, Corrêa AMS, Latorre MDR d O, Santiago SM. The association between domestic violence during pregnancy and low birth weight or prematurity. J Pediatr. 2008;84(1):60–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0021-75572008000100011.

Mahenge B, Likindikoki S, Stöckl H, Mbwambo J. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and associated mental health symptoms among pregnant women in Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BJOG. 2013;120(8):940–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12185.

Silverman JG, Decker MR, Reed E, Raj A. Intimate partner violence victimization prior to and during pregnancy among women residing in 26 U.S. states: associations with maternal and neonatal health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jul;195(1):140–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.052.

Littnerova S, Jarkovsky J, Parenica J, Pavlik T, Spinar J, Dusek L. Why to use propensity score in observational studies? Case study based on data from the Czech clinical database AHEAD 2006–09. Cor et Vasa. 2013 Aug 1;55(4):e383–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crvasa.2013.04.001.

D’Agostino RB. Propensity scores in cardiovascular research. Circulation. 2007;115(17):2340–3. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594952.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the MEASURE DHS project for their support and for free access to the original data.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SY contributed to the study design and conceptualization. SY, EKO and OU reviewed the literature and performed the analysis. NKA provided technical support and critically reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content. SY had final responsibility to submit for publication. All authors read and amended drafts of the paper and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not required for this study since the data is secondary and is available in the public domain. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available at: http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yaya, S., Odusina, E.K., Adjei, N.K. et al. Association between intimate partner violence during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth. BMC Public Health 21, 1610 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11625-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11625-8