Abstract

Background

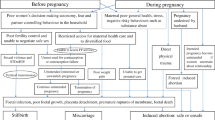

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has been shown to be associated with poor maternal healthcare utilisation and poor pregnancy outcomes. IPV can be seen both as the cause and result of low socioeconomic status and lack of maternal autonomy that can limit women’s access to resources and motivation necessary for seeking healthcare during pregnancy. This paper aims to study the relationship between intimate partner violence (IPV) and the utilisation of facility delivery services in Nigeria.

Methods

We applied propensity score matching (PSM) approach to examine the relationship between intimate partner violence (IPV) and the utilisation of facility delivery services. PSM is a popular strategy for reducing sampling bias through balancing sample characteristics, a technique that mimics randomization on cross-sectional data. Data were collected from Nigeria DHS surveys conducted in 2008 and 2013. IPV was the main explanatory variable of interest for delivery at health facility which was defined as delivering at any health institution including health clinics.

Results

PSM generated 20,446 cases distributed into two equal groups i.e. those who delivered at health facility versus those who did not. The prevalence of facility delivery in 2013 was 56.8% (95%CI 55.0–58.6) indicating a moderate increase from its 2008 level of 43.2% (41.4–45.0%). Lifetime prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual abuse was respectively 21.5%(95%CI 20.6, 22.4), 14.9% (14.2, 15.7) and 5.0% (4.6–5.4). In the multivariable analysis after adjusting for potential confounders, ever experiencing emotional abuse was associated increased odds of not delivering at a health facility. (AOR = 1.228, 95%CI, 1.095–1.679).

Conclusion

Women experiencing emotional violence are less likely to use institutional delivery services, and hence are susceptible to increased risk of reproductive complications. IPV is a complex issue that needs to be tackled by introducing evidence based strategies contextually relevant to local sociocultural environment. Further studies are required to understand the roots of IPV and the pathways through which it hindrances healthcare utilisation among women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is among one of the most common types of violence against women [1,2,3]. It exists throughout the world [4] and is a major public health problem. Approximately 30% of women worldwide have reported physical or sexual abuse by a partner whom they have been in an intimate relationship with [4]. Prevalence of IPV in Sub-Saharan Africa is substantially high, with prevalence estimated between 20 and 70% [4]. Non-governmental organizations, World Health Organisation, and other organizations recognize the problem of IPV and have called on countries to take appropriate measures in reducing IPV against women [5]. Despite the calls made by these organizations, IPV remains rampant and continues to affect millions of women throughout the world [6]. Prevalence of violence against women in Nigeria varies with region and is estimated to be anywhere from 11 to 17% [7,8,9,10,11]. Because there are no standard methods to estimate IPV, there is a wide range in reported prevalence rates. Within Nigeria, violence against women is highly underreported [7,8,9,10].

IPV prevented the attainment of Millennial Development Goals including those pertaining to lowering maternal/child morbidity and mortality [5]. The Millennial Development Goals (MDG) 5 was targeted to improve maternal health, reduce maternal deaths, and create universal access to maternal or reproductive health services by 2015 [12]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) also place strong emphasis on promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment that can reduce the women’s vulnerability to IPV. Conversely, efforts to address IPV will also help achieving the gender violence related SDGs [1]. IPV can lead to complications in pregnancy including miscarriage, bleeding, anaemia and infection amongst others through direct and indirect mechanisms thus lowered the chances of meeting the Millennial Development Goals [5, 9, 13,14,15,16].

Although other studies have looked at the relationship between partner violence and maternal health [17], there have been few studies looking at the impact of IPV on utilisation of maternal health services in Nigeria. Furthermore, given the widespread prevalence of IPV, exploring the relationship between IPV and health facility delivery can be particularly useful for maternal health programs in the country. Therefore, this study used propensity score matching and data collected from Nigeria DHS surveys conducted in 2008 and 2013 to determine the relationship between intimate partner violence (IPV) and the utilisation of facility delivery services in Nigeria. For better understanding of the relationship between IPV and maternal health facility utilisation in Nigeria, the results can be used as a policy tool in order to design programs that will lower IPV and thus increase maternal health facility utilisation within the country.

Methods

The survey and sampling design

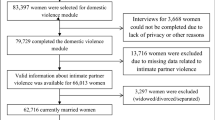

The Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys (NDHS) of 2008 and 2013 were both implemented by the National Population Commission (NPC). Technical and financial assistance were given by Inner City Fund International which came through the USAID funded MEASURE DHS program. DHS collect information on a wide range of health topics including anthropometric, socioeconomic, demographic, family planning and domestic violence. The surveys are nationally representative and include men and women aged 15–49 years old and children under the age of 5 years residing in non-institutional settings. Participants in the surveys were sampled following a three-stage stratified cluster design using a list of enumeration areas (EAs) obtained from the Nigerian 2006 population census. EAs are units selected systematically from localities that constitutes the Local Government Areas (LGAs) – subdivisions of the 36 administrative states that are classified under six developmental zones in Nigeria. For the two NDHS used in this study, 38,948 and 33,385 women were respectively interviewed with a response rate of 98% for the 2013 NDHS and 97% for the 2008 NDHS. The sample selection strategy has been presented in Table 1 and details about the surveys have been published online on the main surveys’ reports.

Variables

Outcome variable was location of most recent childbirth. This was measured by asking the respondent about the place of delivery for the most recent childbirth, and was dichotomised in the following way: (1) Institutional (For deliveries occurring at a Government hospital, District hospital, Private hospital/clinic, Private medical college hospital); and (2) Non-Institutional (For deliveries occurring at respondents’ or relatives’ homes, or in other nonprofessional facilities).

The explanatory variable of focus was three lifetime measures of IPV:

-

Emotional: Ever any emotional violence/ Spouse ever humiliated her/ spouse ever threatened her with harm.

-

Physical: Spouse ever punched with fist or something harmful spouse ever pushed, shook or threw something spouse ever slapped.

-

Sexual: spouse ever forced other sexual acts when not wanted spouse ever physically forced sex when not wanted.

Covariates

Year: 2008/ 2013; Age groups 15–19/ 20–24/ 25–29/ 30–34/ 35–39/ 40–44/ 45–49); type of place of residence: Urban/ Rural; Region: North Central/ North East/ North West/ South East/ South South/ South West; Religion: Christian/ Islam/ Other; Education: no education/ Primary/ Secondary/ Higher; Wealth index: poorest/ poorer/ middle/ richer/ richest; Husbands education: No education/ primary/ secondary/ higher; Sex of household: Male/ Female; Total children born: 1–2/ 3–4/ > 4; Has health insurance: No/ yes.

Data analysis

Data were analysed with SPSS 24. Women who has a childbirth during past five years were included in the analysis. We used propensity score technique that simulates randomisation by matching the groups by outcome status (e.g. user vs non user of facility delivery service) for the predictor variables, which reduces the likelihood of bias in the treatment effect. The main advantage of this method is that it mimics certain characteristics of randomized controlled trials and thereby minimises the bias due to non-randomisation in observational studies. For this study, we used we used logistic regression as estimation algorithm and nearest neighbour matching as matching algorithm with tolerance level of 0.01%. At the first step of the analysis, basic sociodemographic characteristics of the participants were presented as percentages. Prevalence of IPV was calculated for the years 2008 and 2013. Following descriptive analysis, Chi-square (χ2) test was performed to check for the significant associations between the explanatory variables and place of delivery. Variables that were found to be significantly associated in the χ2 tests (at p < 0.25) were selected for final regression analysis. In the final step, binary logistic regression model was used to calculate the odds ratios (OR) of the associations between place of delivery and three types of IPV (physical, emotional, sexual).

Results

In total 20,446 women were included in the study (Table 2). The prevalence of health facility delivery was 43.2% (95%CI = 41.4–45.0) in 2008 and rose to 56.8% (95%CI = 55.0–58.6) in 2013. Table 2 shows that the prevalence was higher among women in the age group of 25–29 years, in the urban areas, located in the South West region, had secondary level education, followers of Christianity, lived in the households with highest wealth quintile, had partners with secondary level education, were from male-headed households, had 1–2 children, had no health insurance.

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of three types of IPVs. Overall, 21.5, 16.1 and 5% of the women reported ever experiencing emotional, physical and sexual violence.

In Fig. 2, about 21.5% reported lifetime experience of emotional violence. The overall proportions of women who had ever been slapped was approximately 14.9%, those who had ever been humiliated was 12.3%. However, lifetime experience of punch or fist with something harmful, pushed shook or threw something, ever forced other sexual acts when not wanted and physically forced sex when not wanted were relatively low among Nigerian women.

Results of regression analysis on the association between place of delivery and three types of IPV were presented in Table 3. In the adjusted models, experiencing emotional (OR = 1. 228, 95%CI = 1.095–1.679) and physical violence (OR = 1.477, 95%CI = 1.128–2.072) were found to be significantly associated with higher odds of not delivering at health facility. That for sexual violence also showed higher odds of not delivering at health facility, however the association was not statistically significant (OR = 1.123, 95%CI = 0.901–1.398).

Discussion

Through this study we were able to determine that women experiencing emotional violence in Nigeria may under-utilize institutional delivery services, and hence are susceptible to increased risk of reproductive complications.

PSM generated 20,446 cases distributed into two equal groups i.e. those who delivered at health facility versus those who did not. The prevalence of facility delivery in 2013 was slightly below half indicating a moderate increase from its 2008 level. A major finding of the study was that most women who delivered at a health care facility were 25–29 years of age, lived in an urban area, were from the South West region, were Christian, had secondary level education, were from the richest or second richest wealth status, and had no health insurance. Other studies have found that the age of women, their family setting, and education level was associated with the level of IPV they experienced [9, 13, 18, 19]. Lifetime prevalence of emotional abuse was highest, physical and sexual abuses were least. Our findings for the prevalence of emotional violence is similar to that of another study conducted in Nigeria that found that 22.4% of women had experienced at least one type of emotional violence by a male partner [20].

In the multivariable analysis after adjusting for potential confounders, ever experiencing emotional abuse was associated increased odds of not delivering at a health facility. Our findings are consistent with another study that found that women who experience emotional violence are less likely to utilise skilled antenatal care, facility delivery and skilled assistance [21]. Another study conducted in Nigeria also found that women who underwent emotional IPV were less likely to use antenatal care [22]. These findings suggest that emotional violence may be playing a less noticeable yet important role in poor utilisation of maternal health services. The possible mechanism by which IPV can reduce the access to healthcare services among women is through affecting their psychosocial situation and health promoting behaviour, which are necessary preconditions for uptake of maternal health care services. In order to boost maternal health services utilisation more attention is needed to be paid to emotional violence. Most studies on IPV have focussed on physical and sexual IPV and their outcomes [23], while there is still little known on the relationship between emotional IPV and utilization of maternal health care services.

In an effort to improve reproductive health in Nigeria, IPV and women’s health right issues are being highlighted in policy making in the country [24]. In many states within the country, The Gender Policy for the Nigeria Police Force (2010) and Gender-based Violence (Prohibition) Law are administered in order to reduce violence against women and as a result, improve women’s health [25]. Despite these initiatives, IPV is still persistent globally [6]. Having a better understanding of the impact of IPV on the choice of maternal health care facility is important. A potential solution can be to lower IPV is by making it, as well as its negative consequences, aware to the public through public enlightenment [26, 27]. Attitude change is also paramount to reducing IPV. Attitude changes can be made by empowering women, promoting gender equality, education, and advocacy as described by the Millennial Development Goals [28,29,30].

Strengths and limitations

The evidence gathered from this study filled an important gap in research and increased our understanding of the association between IPV and utilization of maternal health care facilities. This study also had reduced bias by using applied propensity score matching (PSM) which is used as a popular strategy for reducing sampling bias by balancing sample characteristics, a technique that mimics randomization on cross-sectional data. However, PSM is not without its limitation. An inherent issue is that the investigators do not have control over the exposure to participants and oftentimes it is unlikely that the outcome will be experienced by them for the given context. One important limitation of the study is the possible underreporting of IPV by the study population. Violence is often underreported and there is a chance that some women in the study failed to report IPV that they have experienced [31, 32]. We also used lifetime prevalence of IPV which might have influence the association as the data were collected for the most recent childbirth. Stigmatization as well as personal (embarrassment, economic dependence) and societal reasons (imbalanced power relations between men and women in society) can cause women to underreport IPV [33,34,35].

Conclusion

Intimate partner violence exists in Nigeria. All types of intimate partner violence but especially emotional violence may cause Nigerian women to under-utilise institutional delivery services, and hence making them susceptible to increased risk of reproductive complications. Healthcare policies and programs connected to maternal empowerment, improved behaviour change communication could help address persistent IPV in Nigeria. Further studies are required to understand the causes of IPV and possible pathways by which hinders healthcare utilisation among women as to proffer long-term solutions.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study were sourced from Demographic and Health surveys (DHS) and available here: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Abbreviations

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Survey

- EAs:

-

Enumeration Areas

- IPV:

-

Intimate Partner Violence

- LGAs:

-

Local Government Areas

- PSM:

-

Propensity Score Matching

References

World Health Organization. Violence against women: intimate partner and sexual violence against women. Fact sheet 2016.

Krug EG, et al. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–8.

Garcia-Moreno C, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–9.

World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women : prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. (in IRIS). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. p. 51.

Garcia-Moreno C, Watts C. Violence against women: an urgent public health priority. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:2–2.

Devries KM, Mak JY, García-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, Lim S, Bacchus LJ, Engell RE, Rosenfeld L, Pallitto C, Vos T, Abrahams N, Watts CH. Science. 2013 Jun 28;340(6140):1527–8.

Fawole OI, Aderonmu AL, Fawole AO. Intimate partner abuse: wife beating among civil servants in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9:54–64.

Aimakhu CO, Olayemi O, Iwe CA, Oluyemi FA, Ojoko IE, Shoretire KA, et al. Current causes and management of violence against women in Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:58–63.

Ikeme AC, Ezegwui HU. Domestic violence against pregnant Nigerian women. Trop J Obstet Gyeacol. 2003;20:116–8.

Okemgbo CN, Omideyi AK, Odimegwu CO. Prevalence, patterns and correlates of domestic violence in selected Igbo communities of Imo state, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2002;6:101–14.

Garcia-Moreno C, Watts C. Violence against women: an urgent public health priority. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:2.

Hill PS, et al. From millennium development goals to post-2015 sustainable development: sexual and reproductive health and rights in an evolving aid environment. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21(42):113–24.

Ameh N, Abdul MA. Prevalence of domestic violence amongst pregnant women in Zaria, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2004;3:4–6.

Ezechi OC, Kalu BK, Ezechi LO, Nwokoro CA, Ndububa VI, Okeke GC. Prevalence and pattern of domestic violence against pregnant Nigerian women. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:652–6.

Cokkinides VE, Coker AL, Sanderson M, Addy C, Bethea L. Physical violence during pregnancy: maternal complications and birth outcomes. J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:661–6.

Petersen R, Gazmararian JA, Spitz AM, Rowley DL, Goodwin MM, Saltzman LE, et al. Violence and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a review of the literature and directions for future research. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:366–73.

Stewart, H., Sommerfelt, E., Borwankar, R., Oluwole, D., Fogg, K., and Goings, S. 2010. “Domestic violence against women in sub-Saharan Africa: associations with maternal health”. Presented in commemoration of 16 Days of Activism against Gender Violence 2010.

Hammoury N, Khawaja M, Mahfoud Z, Afifi RA, Madi H. Domestic violence against women during pregnancy: the case of Palestinian refugees attending an antenatal clinic in Lebanon. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18:337–45.

Umeora OU, Dimejesi BI, Ejikeme BN, Egwuatu VE. Pattern and determinants of domestic violence among prenatal clinic attendees in a referral Centre, south-East Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:769–74.

Solanke BL. Association between intimate partner violence and utilisation of maternal health services in Nigeria. Afr Popul Stud. 2014;28(2):933–45.

Hindin MJ, Kishor S, Ansara DL. “Intimate partner violence and couples in 10 DHS countries: predictors and health outcomes”. DHS analytical studies no. 18. Calverton: Macro International Inc; 2008.

Okenwa L, Lawoko S, Jansson B. Contraception, reproductive health and pregnancy outcomes among women exposed to intimate partner violence in Nigeria. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2011;16(1):18–25.

Rahman M, et al. Maternal exposure to intimate partner violence and the risk of undernutrition among children younger than 5 years in Bangladesh. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1336–45.

National Population Commission. National Population Policy for sustainable development. Abuja: National Population Commission; 2004.

Omoluabi E, Aina OI, Attanasso MO. Gender in Nigeria’s development discourse: relevance of gender statistics. African Popul Stud. 2014;27(2) Supp):372–85.

World Health Organization (1997). Violence against women: The priority health issue. Reproductive health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997.

Ibekwe PC. Preventing violence against women: time to uphold an important aspect of the reproductive health needs of women in Nigeria. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2007;33:235–6.

Yaya S, Ghose B. Global inequality in maternal health care service utilization: implications for sustainable development goals. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):145–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2018.0082 eCollection 2019.

Yaya S, Okonofua F, Ntoimo L, Udenigwe O, Bishwajit G. Men's perception of barriers to women's use and access of skilled pregnancy care in rural Nigeria: a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0752-3.

Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Gunawardena N. Socioeconomic factors associated with choice of delivery place among mothers: a population-based cross-sectional study in Guinea-Bissau. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(2):e001341. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001341 eCollection 2019.

Garcia-Moreno C, Stockl H. Violence against women, its prevalence and health consequences. In: Garcia-Moreno C, Riecher-Rossier A, editors. Gender violence and mental health. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2013.

Uwameiye BE, Iserameiya FE. Gender based violence against women and its implication on the girl Child education in Nigeria. Int J Acad Res Prog Educ Dev. 2013;2(1):219–26.

Gracia E. Unreported cases of domestic violence against women: towards an epidemiology of social silence, tolerance, and inhibition. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(7):536–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.019604.

Yaya S, Kunnuji MON, Ghose B. Intimate partner violence: a potential challenge for women’s health in Angola. Challenges. 2019;10:21. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe10010021.

Yaya S, Ghose B. Alcohol drinking by husbands/partners is associated with higher intimate partner violence against women in Angola. Safety. 2019;5(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety5010005.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the MEASURE DHS project for their support and for free access to the original data.

Funding

The authors have no support or funding to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SY and GB contributed to the conception and design of the study. GB did the acquisition of data. SY and NG did the literature review. SY and GB conducted the statistical analysis and interpreted the original results. SY had final responsibility to submit for publication. All authors wrote or reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was not required since the data is secondary and is available in the public domain. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available at: http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Consent for publication

No consent to publish was needed for this study as we did not use any details, images or videos related to individual participants. In addition data used is available in the public domain.

Competing interests

Sanni Yaya is member of the editorial board (Associate Editor) of this journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yaya, S., Gunawardena, N. & Bishwajit, G. Association between intimate partner violence and utilization of facility delivery services in Nigeria: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Public Health 19, 1131 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7470-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7470-1