Abstract

Background

This study determined (1) whether a change in frailty status after a 1 year follow up is associated with healthcare utilization and evaluated (2) whether a change in frailty status after a 1 year follow up and health care utilization are associated with all-cause mortality in a sample of Taiwan population.

Methods

This work is a population-based prospective cohort study involving residents aged ≥65 years in 2009. A total of 548 elderly patients who received follow-ups in the subsequent year were included in the current data analysis. Fried frailty phenotype was measured at baseline and 1 year. Information on the outpatient visits of each specialty doctor, emergency care utilization, and hospital admission during the 2 month period before the second interview was collected through standardized questionnaires administered by an interviewer. Deaths were verified by indexing to the national database of deaths.

Results

At the subsequent 1 year follow-up, 73 (13.3%), 356 (64.9%), and 119 (21.7%) elderly participants exhibited deterioration, no change in status, and improvement in frailty states, respectively. Multivariate logistic analysis showed the high risk of any type of outpatient use (odds ratios [OR] 1.94, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–3.71) among older adults with worse frailty status compared with those who were robust at baseline and had unchanged frailty status after 1 year. After multivariate adjustment, participants with high outpatient clinic utilization had significantly higher mortality than those with low outpatient clinic visits among unchanged pre-frail or frail (hazard ratios [HR] 2.79, 95% CI: 1.46–5.33) and frail to pre-frail/robust group (HR 9.32, 95% CI: 3.82–22.73) if the unchanged robustness and low outpatient clinic visits group was used as the reference group.

Conclusions

The conditions associated with frailty status, either after 1 year or at baseline, significantly affected the outpatient visits and may have increased medical expenditures. Combined change in frailty status and number of outpatient visits is related to increased mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

An aging population is considered one of the most important demographic phenomena worldwide and is frequently referred to as a determinant of healthcare utilization [1, 2]. Community-dwelling older adults face the high risk of becoming frail. In particular, 13.6% of non-frail community older adults become frail after 3 years of follow-up [3]. Frail older adults are vulnerable to adverse health problems, including falls, delirium, fractures, disabilities, hospitalization, institutionalization, and mortality [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Several tools used to define frailty include the frailty index [10], Fried’s frailty phenotype (FFP; Cardiovascular Health Study) [4], the FRAIL scale [11], the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Index [5], Edmonton Frailty Scale [12], and the Tilburg Frailty Indicator [13]. All older adults may be screened for frailty during clinical decision-making to provide more patient centered care, prevent iatrogenic harm, and deliver preventive care [14]. Many studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of preventing or reducing frailty levels in community-dwelling older adults [15, 16]. However, a meta-analysis showed that interventions for frail community-dwelling older adults have no significant effect on adverse outcomes [17]. Frailty is an important risk factor for the health of older adults, thus, epidemiology, natural course, intervention, challenges to healthcare policies concerning frailty, and the effects of frailty on older adults should be investigated.

Previous studies have shown that frail patients are more likely to visit outpatient clinics or consult doctors [18,19,20,21,22], visit the emergency room [18, 22,23,24], be admitted to hospitals [18, 20, 22, 24,25,26,27,28], and use community services [18, 19]. Frailty signifies high healthcare costs [24, 29,30,31] and long-term care costs [32]. However, frailty status is a dynamic process that may change after a certain period [33, 34]. Only a few studies have investigated the association between frailty status changes and medical utilization. Sirven et al. found that an elevated frailty index was associated with an increase in specialist practitioner visits [35]. We aimed to offer additional evidence and explore the relationship between medical utilization and frailty change.

Frailty has been proven to be associated with mortality [4, 6, 7, 9, 10]. The rate of change in frailty [22] and frailty transition [36,37,38,39] have been associated with mortality in some studies. Liu et al. found that worsening frailty and remaining frail increased painful death risk after 3 years of follow-up among 11,165 Chinese older adults [37]. One study involving 1171 community dwelling older Mexican Americans determined that participants who changed their status from pre-frail to frail and frail to pre-frail or those who remained frail faced higher mortality risk than those who remained non-frail in 15 years [36]. Another study conducted among 1353 AIDS patients found that maintained, improved, and intermittent frailty statuses are related to increased mortality [39]. A relation between frailty change and 6-year mortality was reported [38]; however, health utilization and frailty change may be associated with mortality. The combined effects of changes in frailty status and health utilization on subsequent mortality are worthy of investigation. Therefore, the present study had two objectives: (1) to determine whether frailty status at baseline and 1 year can predict changes in healthcare utilization, such as outpatient visits, emergency care visits, and hospital admission in a sample of Taiwan older adults; and (2) to analyze the combined effects of changes in frailty status and healthcare utilization on subsequent mortality.

Methods

Participants

This work was a population-based prospective cohort study comprising 3997 residents aged ≥65 years in 8 administrative neighborhoods at the north district of Taichung City, Taiwan. It was conducted in June 2009. The age and gender distributions in the 8 administrative neighborhoods are similar to those in Taichung and Taiwan populations. All residents received recruitment letters along with the research office’s phone number. Those who called the office and agreed to participate were assigned an appointment date for the interview and physical checkup in a clinical setting. Individuals who were hospitalized, lived in an institution, were not at home when the interviewers visited three times, and refused to participate were excluded. Recruitment was conducted between June 2009 and August 2010. A total of 1347 individuals participated at baseline, with an overall response rate of 49.0%. In the subsequent year, 1078 older adults received follow-up. Among them, 548 subjects who provided completed frailty-related components and medical utilization information at baseline and the 1-year follow-up were included in the present study (Fig. 1).

Frailty status and healthcare utilization measurement

Frailty status was defined on the basis of FFP [4], and it consisted of five components: shrinking, weakness, slowness, poor endurance and energy, and low physical activity level. Shrinking was characterized by an unintentional weight loss of ≥3 kg in the previous year. Weakness referred to the slowest quintile of handgrip strength in the population measured using a handgrip dynamometer (TTM-110D, TTM Co. Japan); it was based on the subgroups of gender and body mass index [40]. Slowness is measured as the slowest quintile of the population in accordance with gender and standing height subgroups and based on a 15 ft. walking time [40]. Considering the racial differences in height and body size between Western and Asian populations, we applied the cut points for weakness and slowness from a pooled analysis study of Taiwan community-dwelling older adults [41], instead of the Fried et al’s cut points, which were determined from Western populations. Endurance and energy were measured from a self-report of exhaustion and identified using two questions from the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale [42]. A low physical activity level was measured on the basis of energy expenditure in accordance with frequency, duration, and types of leisure time activity, as reported by each participant [43]. The lowest quintile of physical activity level in our study sample was identified for each gender. Participants with 0, 1–2, and ≥ 3 frailty phenotype components were considered robust, pre-frail, and frail, respectively [4]. Changes in frailty status during the 1 year period included four categories: (1) deterioration (robust at baseline and pre-frail or frail after 1 year, pre-frail at baseline and frail 1 year later); (2) unchanged pre-frail or frail; (3) unchanged robustness; and (4) improvement (frail at baseline and pre-frail or robust after 1 year; pre-frail at baseline and robust 1 year later).

Data on age, gender, marital status, education, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical behavior, and comorbidity were collected through questionnaires when the participants underwent frailty measurement. Smoking and alcohol drinking habits were categorized as never, current, and former. Regular exercise and physical activity were measured using two independent variables. Regular exercise was measured using one item through respondents’ self-report. Participants who exercised for at least 30 min three times per week during the preceding 6 months were classified as having regular exercise. Physical activity was measured frim the sum of the average time per week spent in each activity multiplied by the metabolic equivalent value.

Information regarding the outpatient visits of each specialist doctor, emergency care utilization, and hospital admission during the 2-month period before baseline and the second interview were collected through standardized questionnaires administered by an interviewer. Outpatient clinic utilization was categorized into two subcategories: rehabilitation and non-rehabilitation. This secondary data analysis study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University Hospital. All the methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Survival assessment

All-cause mortality was evaluated from the date of the second interview until August 31, 2019. Deaths were ascertained using computer linkage with a unique identification number in the national database from the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare. The records of all the deaths of Taiwan citizens are stored in this database and coded from death certificates. Survival time was defined as the time between the second interview and the date of death or the study’s end point.

Statistical analysis

The differences in baseline characteristics among the four groups of frailty status changes within the 1-year period was identified using a chi-square test. To examine the difference of number of outpatient visits among different groups, negative binomial regression was applied because the number of outpatient visits was overdispersed with a variance-to-mean ratio of > 1. Univariate logistic regression models were used to analyze the difference of hospital admission or emergency department visit among different groups. The post hoc comparisons of medical utilization among the three groups of baseline frailty status and among the four groups of frailty status changes was tested using Bonferroni correction. Then, multivariate logistic regression models were used to determine whether frailty status changes were independently associated with outpatient visits, outpatient visits for non-rehabilitation, and hospital admission. The models were used after controlling for age, gender, education, cognitive impairment, regular exercise, and smoking and drinking habits. The associations between frailty status and the number of outpatient visits for 2 months were explored using multivariate negative binomial regression models. The combined effects of frailty status change and outpatient utilization on 9-year mortality were investigated using the Cox proportional hazard models. The proportionality of hazard assumption was confirmed by examining the product term of each independent variable with log follow-up time. For evaluating the potential drop-out bias, sensitivity analyses were performed by using inverse probability weighting (IPW) approach. The first was to derive the predicted probability of non-dropout using a multivariate logistic regression model with covariates, including age, gender, education, cognitive impairment, regular exercise, smoking and drinking status. Then the analysis was performed on non-dropout participants using a weighted model, where the weight of each individual was the inverse of the predicted probability. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 version (SAS, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was considered at p of < 0.05 in all analyses.

Results

A total of 548 older adults were included in this study. In particular, 37 (6.8%), 232 (42.3%), and 279 (50.9%) were respectively categorized as frail, pre-frail, and robust at baseline. In the subsequent year, 73 (13.3%), 356 (65.0%), and 119 (21.7%) of the older adults had deteriorated, did not exhibit any changes, and presented improved FFP components, respectively (Table 1).

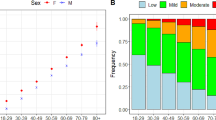

Among the 548 older adults, 313 (57.1%) were male; 208 (38.0%), 140 (25.5%), and 200 (36.5%) were ≤ 70 years old, 71–75 years old, and > 75 years old, respectively; 403 (73.4%) were married; and 385 (70.3%) received education for less than 12 years. Most of older adults have regular exercise (77.8%) and didn’t smoke (78.6%) and didn’t drink (76.6%). The most common chronic diseases was hypertension (51.6%,) (Table 2).

Older adults with improved frailty status outnumbered those with deteriorated status. Gender, age, marital status, educational level, regular exercise, smoking and drinking habits, hypertension history, diabetes history, and frailty status at baseline were significantly associated with frailty status changes (all p values are < 0.05). Older adults with deteriorated FFP status were men, aged ≥75 years, educated for ≥7 years, had regular exercise, engaged in smoking and drinking, and had a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus compared with older adults with improved FFP status (Table 2).

The baseline frailty status suggested that frail and pre-frail older adults reported significantly higher geometric mean numbers of 2-month outpatient visits and non-rehabilitation outpatient visits than robust older adults (1.1 ± 7.6 and 0.9 ± 6.4 for fail; 0.6 ± 8.4 and 0.6 ± 8.3 for pre-frail; 0.4 ± 9.3 and 0.4 ± 9.4 for robust older adults, respectively; Table 3). Changes in medical utilization between baseline and follow-up are similar among the frailty status change groups (Appendix, Table A1). Therefore, the difference in medical utilization at follow-up among these groups was explored. Older adults with unchanged pre-frail or frail status had significantly higher geometric mean numbers of 2-month outpatient and non-rehabilitation outpatient visits than those with deteriorated, improved, and unchanged robust status (0.8 ± 7.5 and 0.8 ± 7.0 for unchanged pre-frail or frail; 0.7 ± 7.1 and 0.7 ± 7.1 for deteriorated; 0.5 ± 9.6 and 0.5 ± 9.4 for improved; and 0.4 ± 9.8 and 0.3 ± 9.6 for unchanged robust older adults, respectively). There was no difference in the number of rehabilitation outpatient visits, proportions of hospital admission and emergency room visits among older adults with different baseline frailty status or change of frailty status (Table 3).

After age, gender, education, cognitive impairment, regular exercise, smoking, and drinking habits were adjusted, multivariate logistic analysis showed that all outpatient and outpatient non-rehabilitation visits were higher among those with unchanged pre-frail or frail status (odds ratios [OR]: 1.94, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.02–3.71 and OR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.04–3.79, respectively), and among those with deteriorated frailty status (OR: 2.01, 95% CI: 0.97–4.18, p = 0.06 borderline significant, and OR: 2.05, 95% CI: 0.99–4.26, p = 0.05 borderline significant, respectively); but not for risks of hospital admission and emergency room visits if unchanged robust status was used as the reference group (Table 4). The association between change of frailty status and outpatient visits disappeared after further adjustment for comorbidity (Appendix, Table A2).

Compared with those of robust older adults at baseline, the adjusted rate ratios of frail and pre-frail older adults were 2.58 [95% CI: 1.82–3.66] and 1.30 [95% CI: 1.07–1.57] in the negative binomial model, respectively. Frail older adults had approximately 141% higher number of outpatient visits in 2 months than robust older adults (p < 0.05; Fig. 2).

The independent effects of change in frailty status and the utilization of 2-month outpatient clinic on mortality were examined. Only the independent effects of frailty either at baseline or 1-year were found, but the independent effect of utilization outpatient clinic at 1-year follow-up was not exist (Appendix, Table A3). Furthermore, the combined effects of changes in frailty status and in the number of outpatient visits on 9-year mortality were explored using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models. The median follow-up duration was 8.83 years (at the end of August 2019). Given that the mortality of the pre-frail to robust and frail to pre-frail/ robust group was different, the groups were separated from the improvement group according to the change in frailty status (Table 5). Among the groups, the group with unchanged robustness and low outpatient clinic utilization had the lowest mortality rate (12.5%), and the frail to pre-frail/robust group and high outpatient clinic utilization group had the highest mortality rate (75.0%). Individuals with high outpatient clinic utilization had relatively higher mortality than those with low outpatient clinic utilization among most groups. Participants who improved from pre-frail to robust had lower mortality rate (17.9, 19.0%) compared with the deterioration (24.3, 27.8%) and unchanged pre-frail / frail group (35.3, 37.9%). After adjusting for age, gender, education, cognitive impairment, regular exercise, smoking, and drinking, individuals with high outpatient clinic utilization had significantly higher mortality than those with low outpatient clinic visits among unchanged pre-frail or frail (HR 2.79, 95% CI: 1.46–5.33) and frail to pre-frail/robust group (HR 9.32, 95% CI: 3.82–22.73) if the group with unchanged robustness and low outpatient clinic visits was used as the reference group. Either change in frailty status or high number of outpatient visits was related to increased mortality. The combined association of change in frailty status and outpatient utilization with mortality remained statistically significant after additional adjustment for comorbidity (hypertension and diabetes) (Appendix, Table A4). In addition to this, sensitivity analysis using IPW approach was performed for controlling potential drop-out bias. (Appendix, Table A5, Table A6, and Fig. A1). Some of these analyses using IPW approach yielded comparable results, some of them became attenuated, and some of them became significant with direction similar to the original analyses.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between baseline and 1-year frailty status changes and healthcare utilization. Results show that frailty status, either at baseline or 1-year change, is associated with healthcare utilization during outpatient visits, which may possibly increase medical expenditures.

In our study, frail older adults reported significantly higher proportions of outpatient and non-rehabilitation outpatient visits. Several previous studies showed that frailty is positively associated with healthcare utilization, such as outpatient clinic visits or doctor consultation [18,19,20,21] and hospital admission, and these results are consistent with the present findings [18, 20, 24, 25]. However, the present study did not reveal the association between frailty status and hospital admission or emergency room visits and is inconsistent with the previous studies [18, 23, 24]. In this study, only 6 (1.1%) and 5 (0.9%) participants were admitted to the hospital or visited the emergency department during the 2-month period before the interview. The number of participants who have hospital admission and emergency department use was very limited, which cannot meet the required number of participants for inadequate statistical power. The baseline frailty status is not associated with outpatient rehabilitation visits in our study. However, a previous study suggested that rehabilitation is effective in frail and pre-frail older adults [44]. Frail older adults should receive rehabilitation to improve their frailty status in the future.

Aside from the baseline frailty status, related changes are also associated with healthcare utilization in our study. Compared with older adults with unchanged robustness, those with unchanged pre-frail or frail were associated with increased risk of outpatient clinic visits and non-rehabilitation use. Sirven et al. used the frailty index to define frailty and concluded that elevated frailty index is associated with the increase in the number of specialist practitioners visit [35]. This finding is consistent with our results. In the present study, all participants obtained the result of their own frailty screen test. Given the convenient and cheap medical environment in Taiwan, pre-frail and frailty older adults may visit doctors to find the reversible causes of frailty and adjust their diet or increase exercise and physical activity. Such steps may result in changes in frailty status and medical utilization. If the health status of pre-frail or frail elders does not change, the use of outpatient clinic will be continuous due to health need.

In addition, the combined effect of frailty change and health utilization on 9-year all-cause mortality was observed. In this cohort, the 1-year change in frailty status and the 6-year all-cause mortality are related [38]. Other previous studies also revealed the relationship with frailty transition and mortality [36, 37, 39]. Furthermore, our findings indicated that the combined effects of the change in frailty status and outpatient utilization on 9-year mortality were significant. The present results indicate the hazard ratios of mortality were greater among elderly with high outpatient clinic utilization and with either improvement from frail to pre-frail/robustness or unchanged frailty status than those among elderly with low outpatient clinic utilization and unchanged robustness. Given the same change of frailty status, higher mortality rate was found in older adults with high healthcare utilization than in those with low utilization. A possible explanation for the phenomena is that high healthcare utilization may raise the risk of adverse outcome due to polypharmacy if elderly care is not integrated well in practice. A previous study reported the prevalence of potential drug-drug interactions in Taiwan was 25% [45]. It was implied that older adults with high health utilization are potentially at increased risk of polypharmacy and drug interactions which is more likely to experience adverse outcome. In general, high medical utilization might reflect the increasing medical needs of the elderly. For the elderly with frailty and frequent outpatient clinic visits, integrated geriatric medicine practice is needed. Doctors might need to address polypharmacy, manage sarcopenia, and find out the treatable causes of weight loss and the causes of exhaustion to improve their frailty status to decrease mortality [46].

However, we observed that individuals who had improved frail status and were frail at baseline and high outpatient clinic utilization had the highest mortality rate. In addition, individuals with improvement of frail status and low outpatient clinical utilization were associated with an increased risk of mortality in sensitivity analysis with IPW. One possible explanation is that elderly people with improved frail status may have underlying illness resulting in high risk of death. Another possible explanation is the improvement of these older adults might not sustain, because the frailty status is a dynamic stage with frequent transitions over time [47]. For clinical practice and future study, frail status in older adults should be regularly monitor. It can be considered as relative stable status if the change of frailty at two years have been observed consistently.

Participants who improved from pre-frail to robust had relatively lower mortality rate than rate of adults improved from frail to prefrail/ robust. Baseline frailty status seemed to have stronger predictive effect than frailty change. To decrease the mortality of the older adults, we should try to prevent frailty in the population by monitoring physical reserve, performing regular exercise, vaccinating for preventable diseases, undergoing prehabilitation before anticipated loss and using comprehensive geriatric evaluation and management [48].

This study has three main advantages. This work is a population-based study and the first to investigate the association between FFP status changes and medical utilization. This study is also the first to investigate the combined effect of frailty transition and medical utilization to mortality. This study has several main limitations. First, healthcare utilization information was obtained using questionnaires; therefore, recall bias is possible. However, Short ME et al. [49] suggested that self-reported healthcare utilization can be used as a proxy when medical claims and administration data, especially yearly and monthly emergency room and inpatient admissions, cannot be obtained. In this study, self-reported bias may not be severe because participants were asked to recall their recent 2-month medical utilization only to minimize the recall task for them. A longer recall period not only increases the recall task of elderly participants, but also increases the recall bias. Brusco and Watts found 35% over–reporting when older patients were asked the numbers of general practice visits in the past 6 months compared to national insurer claims data over the same period [50]. Second, our analysis was restricted to older adults who underwent comprehensive exam at baseline and after 1 year. Those who were extremely frail and sick may not be able to follow, and sample drop-out bias may be present. However, those subjects who were excluded in the analysis of this study were more likely to die (9-year mortality rate, 37.7%). We can still detect the impact of frailty changes and healthcare utilization on mortality. We used IPW approach to control the drop-out bias and the results remained similar. Third, only the 2-month healthcare utilization information prior to the second frailty status evaluation was obtained. According to a systematic review study that evaluates the relationship between frailty and hospitalization states, the follow-up period of other studies were 10 months to 5.9 years [27]. The unchanged robust group was not admitted to the hospital, and the deteriorated group did not visit the emergency room during the 2 month study period (Table 4). Given that the present study population was relatively robust, the medical hospitalization and emergency room states of the participants were limited; this factor may have affected the statistical power. Fourth, we adjusted for as many confounders as possible to minimize the effect of potential confounders, but we cannot entirely exclude the possibility of residual confounding, such as new-onset diseases and health behavior changes in the time period between frailty measurement and mortality data collection. Fifth, our findings may not be applicable elsewhere because of differences in healthcare systems, Finally, comorbidity factors were not included in the multivariate model in contrast to those in other studies [19, 20, 29], and the underlying diseases may affect healthcare utilization. However, multimorbidity is associated with frailty [51]. If they were examined using the regression model simultaneously, multicollinearity might occur and induce bias.

Conclusions

The conditions associated with frailty status, either at baseline or 1 year, highly affect outpatient clinic visits. Thus, healthcare utilization and expenditures may increase, and improvement in or maintenance of robustness in frailty status may decrease outpatient visits. The changes in frailty status and number of outpatient visits are related to mortality. Older adults who remain robust for 1 year have a low mortality rate. Given that frailty is a dynamic process, frailty evaluation should be performed periodically to respond fast if frailty deteriorates. Further research on the relationship of frailty transition and other outcomes, such as life quality, may be considered in the future.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the policy declared by Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HR:

-

Hazard ratios

- FFP:

-

Fried’s frailty phenotype

- IPW:

-

Inverse probability weighting

References

Nouraei Motlagh S, Sabermahani A, Hadian M, Lari MA, Mahdavi MR, Abolghasem Gorji H. Factors affecting health care utilization in Tehran. Global J Health Sci. 2015;7(6):240–9.

Beard JR, Bloom DE. Towards a comprehensive public health response to population ageing. Lancet. 2015;385(9968):658–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61461-6.

Ofori-Asenso R, Chin KL, Mazidi M, Zomer E, Ilomaki J, Zullo AR, et al. Global incidence of frailty and Prefrailty among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198398. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8398.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146.

Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, Fink HA, Cawthon PM, Stone KL, et al. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):382–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2007.113.

Evans SJ, Sayers M, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. The risk of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older patients in relation to a frailty index based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Age Ageing. 2014;43(1):127–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft156.

Chamberlain AM, Finney Rutten LJ, Manemann SM, Yawn BP, Jacobson DJ, Fan C, et al. Frailty trajectories in an elderly population-based cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):285–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13944.

Koyama S, Katata H, Ishiyama D, Komatsu T, Fujimoto J, Suzuki M, et al. Preadmission frailty status as a powerful predictor of dependency after discharge among hospitalized older patients: a clinical-based prospective study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(12):1609–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13537.

Ofori-Asenso R, Chin KL, Sahle BW, Mazidi M, Zullo AR, Liew D. Frailty confers high mortality risk across different populations: evidence from an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Geriatrics. 2020;5(1):17.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/62.7.722.

Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(7):601–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-012-0084-2.

Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton frail scale. Age Ageing. 2006;35(5):526–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl041.

Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. The Tilburg frailty indicator: psychometric properties. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(5):344–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2009.11.003.

Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1365–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31786-6.

Puts MTE, Toubasi S, Andrew MK, Ashe MC, Ploeg J, Atkinson E, et al. Interventions to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a scoping review of the literature and international policies. Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):383–92.

Apostolo J, Cooke R, Bobrowicz-Campos E, Santana S, Marcucci M, Cano A, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent pre-frailty and frailty progression in older adults: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(1):140–232. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003382.

Van der Elst M, Schoenmakers B, Duppen D, Lambotte D, Fret B, Vaes B, et al. Interventions for frail community-dwelling older adults have no significant effect on adverse outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):249. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0936-7.

Hoeck S, Francois G, Geerts J, Van der Heyden J, Vandewoude M, Van Hal G. Health-care and home-care utilization among frail elderly persons in Belgium. Eur J Pub Health. 2012;22(5):671–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckr133.

Rochat S, Cumming RG, Blyth F, Creasey H, Handelsman D, Le Couteur DG, et al. Frailty and use of health and community services by community-dwelling older men: the Concord health and ageing in men project. Age Ageing. 2010;39(2):228–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afp257.

Ilinca S, Calciolari S. The patterns of health care utilization by elderly Europeans: frailty and its implications for health systems. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(1):305–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12211.

Blodgett JM, Theou O, Howlett SE, Wu FC, Rockwood K. A frailty index based on laboratory deficits in community-dwelling men predicted their risk of adverse health outcomes. Age Ageing. 2016;45(4):463–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw054.

Fillion V, Sirois MJ, Gamache P, Guertin JR, Morin SN, Jean S. Frailty and health services use among Quebec seniors with non-hip fractures: a population-based study using adminsitrative databases. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3865-z.

Dent E, Dal Grande E, Price K, Taylor AW. Frailty and usage of health care systems: results from the south Australian monitoring and surveillance system (SAMSS). Maturitas. 2017;104:36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.07.003.

Garcia-Nogueras I, Aranda-Reneo I, Pena-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J, Abizanda P. Use of health resources and healthcare costs associated with frailty: the FRADEA study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(2):207–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0727-9.

Comans TA, Peel NM, Hubbard RE, Mulligan AD, Gray LC, Scuffham PA. The increase in healthcare costs associated with frailty in older people discharged to a post-acute transition care program. Age Ageing. 2016;45(2):317–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv196.

Chao CT, Wang J, Chien KL, group COoGNiNs. Both pre-frailty and frailty increase healthcare utilization and adverse health outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0772-2.

Kojima G. Frailty as a predictor of hospitalisation among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(7):722–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206978.

Forti P, Rietti E, Pisacane N, Olivelli V, Maltoni B, Ravaglia G. A comparison of frailty indexes for prediction of adverse health outcomes in an elderly cohort. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):16–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2011.01.007.

Bock JO, Konig HH, Brenner H, Haefeli WE, Quinzler R, Matschinger H, et al. Associations of frailty with health care costs--results of the ESTHER cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):128. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1360-3.

Robinson TN, Wu DS, Stiegmann GV, Moss M. Frailty predicts increased hospital and six-month healthcare cost following colorectal surgery in older adults. Am J Surg. 2011;202(5):511–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.06.017.

Hajek A, Bock JO, Saum KU, Matschinger H, Brenner H, Holleczek B, et al. Frailty and healthcare costs-longitudinal results of a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2018;47(2):233–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx157.

Peters LL, Burgerhof JG, Boter H, Wild B, Buskens E, Slaets JP. Predictive validity of a frailty measure (GFI) and a case complexity measure (IM-E-SA) on healthcare costs in an elderly population. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(5):404–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.09.015.

Bentur N, Sternberg SA, Shuldiner J. Frailty transitions in community dwelling older people. Isr Med Assoc J. 2016;18(8):449–53.

Ofori-Asenso R, Lee Chin K, Mazidi M, Zomer E, Ilomaki J, Ademi Z, et al. Natural regression of frailty among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2020;60(4):e286–98.

Sirven N, Rapp T. The dynamics of hospital use among older people evidence for Europe using SHARE data. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(3):1168–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12518.

Li CY, Al Snih S, Karmarkar A, Markides KS, Ottenbacher KJ. Early frailty transition predicts 15-year mortality among nondisabled older Mexican Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(6):362–7e363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.03.021.

Liu ZY, Wei YZ, Wei LQ, Jiang XY, Wang XF, Shi Y, et al. Frailty transitions and types of death in Chinese older adults: a population-based cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:947–56. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S157089.

Wang MC, Li TC, Li CI, Liu CS, Lin WY, Lin CH, et al. Frailty, transition in frailty status and all-cause mortality in older adults of a Taichung community-based population. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1039-9.

Piggott DA, Bandeen-Roche K, Mehta SH, Brown TT, Yang H, Walston JD, et al. Frailty transitions, inflammation, and mortality among persons aging with HIV infection and injection drug use. AIDS. 2020;34(8):1217–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002527.

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):255–63.

Wu IC, Lin CC, Hsiung CA, Wang CY, Wu CH, Chan DC, et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among community-dwelling older adults in Taiwan: a pooled analysis for a broader adoption of sarcopenia assessments. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(Suppl 1):52–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12193.

Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ. Factorial and discriminant validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42(1):28–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198601)42:1<28::AID-JCLP2270420104>3.0.CO;2-T.

Taylor HL, Jacobs DR Jr, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31(12):741–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9.

Cameron ID, Kurrle SE. Frailty and rehabilitation. Interdiscip Top Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;41:137–50. https://doi.org/10.1159/000381229.

Lin CF, Wang CY, Bai CH. Polypharmacy, aging and potential drug-drug interactions in outpatients in Taiwan: a retrospective computerized screening study. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(3):219–25. https://doi.org/10.2165/11586870-000000000-00000.

Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Woodhouse L, Rodriguez-Manas L, Fried LP, et al. Physical frailty: ICFSR international clinical practice guidelines for identification and management. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23(9):771–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-019-1273-z.

Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, Han L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):418–23.

Walston J, Buta B, Xue QL. Frailty screening and interventions: considerations for clinical practice. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(1):25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2017.09.004.

Short ME, Goetzel RZ, Pei X, Tabrizi MJ, Ozminkowski RJ, Gibson TB, et al. How accurate are self-reports? Analysis of self-reported health care utilization and absence when compared with administrative data. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(7):786–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a86671.

Brusco NK, Watts JJ. Empirical evidence of recall bias for primary health care visits. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1039-1.

Vetrano DL, Palmer K, Marengoni A, Marzetti E, Lattanzio F, Roller-Wirnsberger R, et al. Frailty and multimorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol: Ser A. 2018;73(5):gly110.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan (NHRI-EX98-9838PI), China Medical University Hospital (DMR-109-097) and Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 105–2314-B-039-021-MY3, MOST 105–2314-B-039-025-MY3, and MOST 108–2314-B-039-031-MY2). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CML and CCL contributed equally to the design of the study and the direction of its implementation, including supervision of the field activities, quality assurance and control. CHL, CIL, CSL, and WYL supervised the field activities. CML, TCL and CCL helped conduct the literature review and prepare the Methods and the Discussion sections of the text. CIL designed the study’s analytic strategy and conducted the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of China Medical University Hospital (DMR 97-IRB-055). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant for the first and second waves of data collection. The present study was also approved by REC (CMUH105-REC1–026), the informed consent was not required because the study was a secondary data analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table A1.

Medical utilization in 2 months at baseline, 1 year follow-up, and difference among the elderly with different change in frailty status after 1 year follow-up. Table A2. Change in frailty status and medical utilization via the multivariate logistic regression models after adjusting for baseline age, gender, cognitive impairment, regular exercise, smoking, drinking status and co-morbidity (hypertension and diabetes). Table A3. Independent effects of change in frailty status and the utilization of 2-month outpatient clinic on 9-years mortality via Cox proportional hazard model. Table A4. Combined effects of change in frailty status and the utilization of 2 months outpatient clinic on 9 years mortality via Cox proportional hazard model with additional adjustment for co-morbidity. Fig. A1. Sensitivity analysis for association between frailty status and the number of outpatient visits in 2 months. Negative binomial regression models with inverse probability weighting approach for controlling potential drop-out bias were adjusted for baseline age, gender, education, cognitive impairment, regular exercise, smoking and drinking status. Table A5. Sensitivity analysis of change in frailty status and medical utilization via the multivariate logistic regression models with inverse probability weighting approach for controlling potential drop-out bias. Table A6. Sensitivity analysis of combined effects of change in frailty status and utilization of 2-month outpatient clinic on 9-year mortality via the Cox proportional hazard models with inverse probability weighting approach for controlling potential drop-out bias.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, CM., Lin, CH., Li, CI. et al. Frailty status changes are associated with healthcare utilization and subsequent mortality in the elderly population. BMC Public Health 21, 645 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10688-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10688-x