Abstract

Background

The prevalence of alcohol intake is increasing among women in some populations. Alcohol consumption plays an important role in the risk of major cardiovascular outcomes and total mortality. Here, we conducted a meta-analysis to estimate the association between alcohol intake and major cardiovascular outcomes or total mortality in women compared with men.

Methods

We searched the PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library databases for relevant articles published prior to June 2014. Among these potential included prospective studies, the different dose categories of alcohol intake were compared with the lowest alcohol intake or non-drinkers between women and men for the outcomes of major cardiovascular or total mortality.

Results

We included 23 prospective studies (18 cohorts) reporting data on 489,696 individuals. The summary relative risk ratio (RRR; female to male) for total mortality was significantly increased with moderate alcohol intake compared with the lowest alcohol intake (RRR, 1.10; 95 % confidence interval [CI]: 1.00–1.21; P = 0.047); no such significance was observed with other levels of alcohol intake (low intake: RRR, 1.07; 95 % CI: 0.98–1.17; P = 0.143; heavy intake: RRR, 1.09; 95 % CI: 0.99–1.21; P = 0.084). There was no evidence of a sex difference in the relative risk for coronary disease, cardiac death, stroke, or ischemic stroke between participants with low to heavy alcohol intake compared with those who never consumed alcohol or had the lowest alcohol intake.

Conclusions

Women with moderate to heavy alcohol intake had a significantly increased risk of total mortality compared with men in multiple subpopulations. Control of alcohol intake should be considered for women, particularly for young women who may be susceptible to binge drinking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alcohol is a commonly consumed beverage in many populations, and contributes both favorably and adversely to disease morbidity and mortality [1]. A large number of cohort studies have shown that light-to-moderate alcohol intake is associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease and ischemic stroke, and that heavy intake is associated with an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke among men [2–7]. Previous studies [8, 9] have indicated that women with light-to-moderate alcohol intake have a significantly lower relative risk of cardiovascular disease compared to male drinkers, furthermore, there are some debate as to whether this sex difference is true for the association between alcohol intake and major cardiovascular outcomes or total mortality.

In 1998, the Multiethnic Prospective Cohort (MPC) study [10] indicated that women with heavy alcohol intake had a 203 % greater stroke risk and 17 % greater total mortality risk compared to men. However, in the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study [9], the risk of coronary disease was found to be 67 % lower in women with heavy alcohol intake compared with men. Similarly, the risk of coronary disease was found to be 55 % lower in women with moderate alcohol intake compared to men in the Danish National Cohort Study (DANCOS) [8]. The reasons for this variation in the sex-specific association between alcohol intake and subsequent major cardiovascular outcomes could be the different study designs, the classification of alcohol type, and the different adjusted confounding factors.

At present, it is unclear whether women who consume alcohol are at a greater risk or a benefit of major cardiovascular outcomes than men. Herein, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available prospective observational studies to evaluate those effects of alcohol intake on the subsequent risk of major cardiovascular outcomes or total mortality in women compared with men.

Methods

Data sources, search strategy, and selection criteria

This review was conducted and was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Statement issued in 2009 [11]. Any prospective observational study that evaluated the association between alcohol intake and subsequent major cardiovascular outcomes or total mortality risk in men and women was eligible for inclusion in our study, and no restrictions were placed on language or publication status. Relevant studies were identified using the following procedure:

-

1.

Electronic searches: We searched the PubMed, Embase, Ovid, and the Cochrane Library databases for articles published through June 2014. Both medical subject headings and free-language terms of “ethanol” or “alcohol” or “alcoholic beverages” or “drinking behaviour” or “alcohol drinking” AND (“stroke” or “cardiovascular diseases” or “myocardial infarction” or “myocardial ischemia” or “coronary artery disease” or “heart infarction”) AND “men” AND “women” AND (“cohort” or “prospective” or “nested case–control”)were used as search terms (Additional file 1).

-

2.

Other sources: Meeting abstracts, references of meta-analyses, and reviews already published on related topics were examined. Authors were contacted for essential information regarding publications that were not available in full. The medical subject heading, methods, population, study design, exposure, and outcome variables of these articles were used to identify relevant studies.

The literature search, data extraction, and quality assessment were independently undertaken by two investigators (YHZ and CZ) using a standardized approach. Any inconsistencies between these investigators were identified by the primary investigator (JH) and resolved by consensus. We restricted our study to prospective observational studies that were less likely to be subject to confounding variables or bias compared to traditional case control studies [12]. A study would be eligible for inclusion in our meta-analysis if the following criteria were met: (1) the study was a prospective observational study (prospective cohort study or nested case control study); (2) the study investigated the association between alcohol intake and the risk of major cardiovascular outcomes or total mortality in men and women separately; and (3) the authors reported effect estimate (risk ratio [RR], odds ratio [OR], or hazard ratio [HR]) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) on cardiovascular outcomes (coronary disease, total mortality, cardiac death, stroke, and ischemic stroke) for comparisons of different dosage of alcohol intake with the lowest alcohol intake or non-drinking.

Data collection and quality assessment

The information collected the included group’s name, country, study design, sample size for men and women, age at baseline, percentage of sample size for different alcohol intake categories, follow-up duration, and covariates in the fully adjusted model. We also extracted the effect estimate and its 95 % CIs. For studies that reported several multivariable adjusted RRs, we selected the effect estimate that was maximally adjusted for potential confounders.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) has been partially validated for evaluating the quality of observational studies, was employed to evaluate methodological quality [13, 14]. The NOS is based on the following three subscales: selection (four items), comparability (one item), and outcome (three items). A “star system” (range, 0–9) has been developed for assessment [13]. The data extraction and quality assessment were conducted independently by two authors (YHZ and FL). Referring to the original studies, information was examined and adjudicated independently by an additional author (JH).

Statistical analysis

We examined the relationship between alcohol intake and the risk of major cardiovascular outcomes or total mortality in women compared with men based on the effect estimate (RR, OR, or HR) and its 95 % CI in each study. For every study, sex-specific RRs and 95 % CIs were used to estimate the female-to-male ratio of RRs (relative risk ratio [RRR]) and its 95 % CIs [15]. First, we used a random effects model to calculate summary RRs and 95 % CIs for different exposure categories versus the lowest alcohol intake in men and women separately. Next, both fixed-effect and random-effect models were used to evaluate the pooled RRR for the comparison of different exposure categories versus the lowest alcohol intake in women compared with men; the results from the random-effect model which assumed that the true underlying effect varied among included trials, were presented here [16, 17].

Heterogeneity between studies was investigated using the Q statistic, and we considered P-values of < 0.10 as indication of significant heterogeneity [18–20]. Subgroup analyses were conducted for coronary disease or total mortality based on the country, sample size, physical activity, serum cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, follow-up duration, and the study quality.

We also performed a sensitivity analysis by removing a specific study from the meta-analysis [21]. Several methods were used to check for potential publication bias. Visual inspections of funnel plots for coronary disease and total mortality were conducted. The Egger [22] and Begg tests [23] were also used to statistically assess publication bias for coronary disease and total mortality. All reported P-values were 2-sided and P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant for all included studies. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (version 12.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Studies and patient characteristics

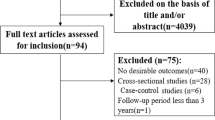

The results of the study selection process were shown in Fig. 1. We identified 2,567 articles in our initial electronic search, of which 2,436 were excluded because they were duplicate or irrelevant articles. A total of 131 potentially eligible studies were selected. After detailed evaluations, 23 prospective studies including 18 cohorts were selected for the final meta-analysis [8–10, 24–43]. A manual search of the reference lists within these studies did not yield any new eligible studies. The general characteristics of the included studies were presented in Tables 1 and Additional file 2: Table S1.

Of the 18 included cohorts, reporting data on 489,696 individuals, 16 cohorts (20 studies) had been examined using a prospective cohort study design [8–10, 24–37, 39, 42, 43], and the remaining two cohorts (three studies) had been examined by using a prospective nested case control study design [38, 40, 41]. The follow-up period for participants was 5.0–20.0 years, and 1,620–114,928 individuals were included in each study. A total of six cohorts (seven studies) were conducted in the US [10, 24, 26, 30, 31, 42, 43], ten (13 studies) were conducted in Europe [8, 25, 27–29, 32, 33, 35, 37–41], and two (three studies) were conducted in other countries [9, 34, 36]. Study quality was assessed using the NOS. Overall, two cohorts had a score of 9 [29, 34–36], four cohorts had a score of 8 [9, 24, 32, 33, 42, 43], seven cohorts had a score of 7 [8, 10, 27, 28, 31, 37, 39], three cohorts had a score of 6 [25, 30, 38], and the remaining two cohorts had a score of 5 [26, 40, 41].

Coronary disease

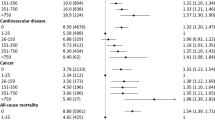

A total of nine cohorts (11 studies) reported an association between alcohol intake and the risk of coronary disease [8–10, 27, 29, 32, 33, 38–41]. The summary RR of the associated between alcohol intake and coronary disease in men and women, were separately listed in Table 2. The pooled RRR (female to male) of low alcohol intake (<15 g/day) versus the lowest alcohol or no alcohol intake was 1.01 (95 % CI: 0.84–1.21; P = 0.947; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S1), with no evidence of heterogeneity among included studies . Furthermore, the pooled RRR (female to male) was 0.96 (95 % CI: 0.75–1.23; P = 0.772; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S2) for moderate alcohol intake (15–30 g/day). There was a significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 40.7 %; P = 0.096). Finally, the pooled RRR (female to male) was reduced by 10 % (RRR, 0.90; 95 % CI: 0.66–1.22; P = 0.503; with moderate heterogeneity; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S3) for heavy alcohol intake (>30 g/day), but this reduction was not statistically significant.

Total mortality

A total of 10 cohorts (14 studies) reported an association between alcohol intake and the risk of total mortality [8, 10, 25–29, 34–36, 40–43]. The summary RR of the associated between alcohol intake and total mortality in men and women, were separately listed in Table 2. The pooled RRR (female to male) for moderate alcohol intake and the risk of total mortality was statistically significantly increased (RRR, 1.10; 95 % CI: 1.00–1.21; P = 0.047; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S5). Although the summary RRR (female to male) increased, there was no significant association between low (RRR, 1.07; 95 % CI: 0.98–1.17; P = 0.143; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S4) or heavy alcohol intake (RRR, 1.09; 95 % CI: 0.99–1.21; P = 0.084; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S6) and the risk of total mortality in women compared with men.

Cardiac death, stroke, and ischemic stroke

The breakdown for the number of cohorts available for each outcome were four (seven studies), five (seven studies), and three (five studies) for cardiac death [25, 31, 34–36, 42, 43], stroke [10, 30, 34–38], and ischemic stroke [24, 30, 34–36] respectively. These associations in men and women separately were shown in Table 2. The summary RRRs (female to male) of low alcohol intake were 0.93, 0.99, and 0.94 for cardiac death (RRR, 0.93; 95 % CI: 0.83–1.04; P = 0.216; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S8), stroke (RRR, 0.99; 95 % CI: 0.83–1.16; P = 0.864; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S9), and ischemic stroke (RRR, 0.94; 95 % CI: 0.74–1.20; P = 0.633; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S7) respectively. Similarly, the summary RRRs (female to male) of moderate alcohol intake were 0.99, 0.90, and 0.88 for cardiac death (RRR, 0.99; 95 % CI: 0.87–1.14; P = 0.934; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S10), stroke (RRR, 0.90; 95 % CI: 0.74–1.10; P = 0.299; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S11), and ischemic stroke (RRR, 0.88; 95 % CI: 0.66–1.16; P = 0.366; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S12) respectively. Finally, the summary RRRs (female to male) of low alcohol intake were 1.44, 1.35, and 1.04 for cardiac death (RRR, 1.14; 95 % CI: 0.99–1.32; P = 0.075; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S13), stroke (RRR, 1.35; 95 % CI: 0.77–2.35; P = 0.292; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S14), and ischemic stroke (RRR,1.04; 95 % CI: 0.80–1.36; P = 0.762; Table 2 and Additional file 2: Figure S15) respectively.

Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis

Sensitivity analyses indicated that exclusion of any individual study did not significantly alter the results (data not shown). Heterogeneity testing for the analysis showed P >0.10 for coronary disease and total mortality. We concluded that heterogeneity was not significant in the overall analysis, which suggested that most variation was attributable to chance alone. Subgroup analyses were also conducted for coronary disease and total mortality to evaluate the effect of alcohol intake in women compared with men in specific subpopulations. The summary RRR (female to male) was significantly increased for the association between moderate alcohol intake and the risk of coronary disease for studies conducted in the US. Furthermore, the summary RRR (female to male) was significantly increased for the association between heavy alcohol intake and subsequent total mortality risk for studies conducted in the US. The study was not adjusted for physical activity, diabetes, or low NOS score (Table 3).

Publication bias

Review of the funnel plots could not rule out the potential for publication bias for the risk of coronary disease, and total mortality. The Egger [22] and Begg test [23] results showed no evidence of publication bias for the risk of coronary disease (low [Additional file 2: Figure S16], moderate [Additional file 2: Figure S17] and heavy alcohol intake [Additional file 2: Figure S18]), total mortality (low [Additional file 2: Figure S16], moderate [Additional file 2: Figure S17] and heavy alcohol intake [Additional file 2: Figure S18]) in women compared with men.

Discussion

Our current study was based on prospective observational studies and was used to explore all possible correlations between alcohol intake and coronary disease, total mortality, cardiac death, stroke, or ischemic stroke in women compared with men. This large quantitative study included 489,696 individuals from 18 prospective cohorts across a broad range of populations. Under the condition of without considering other independent cardiovascular risk factors, the findings of this meta-analysis indicated that female with moderate alcohol intake had a 10 % greater RR of total mortality than male drinkers. Furthermore, subgroup analyses indicated that among US participants, women with moderate alcohol intake had an increased risk of coronary disease (117 %) compared to male drinkers, and that women with heavy alcohol intake had a 16 %, 16 %, 16 %, and 15 % greater RR of total mortality than male drinkers for the study conducted in US, the study not adjusted for physical activity, the study not adjusted for diabetes, or the study with low NOS score respectively.

A previous meta-analysis [44] suggested that the increased alcohol intake was associated with a reduced risk of coronary disease in men and women, but there was no significant difference in the effect of alcohol intake and subsequent coronary disease risk between men and women. The inherent limitation of that previous review was that the study did not provide the results of gender difference. The current study indicated that low-to-heavy alcohol intake might be protective against coronary disease risk in men and women, separately. Furthermore, although the summary RRR (female to male) was slight reduced for the association between moderate or heavy alcohol intake and the risk of coronary disease in women compared with men, the reduction was not statistically significant. Finally, subgroup analyses indicated that there was no statistical evidence for differing beneficial effects of alcohol intake and subsequent risk of coronary disease between men and women, except in US participants. A possible reason for this could be that women had a lower gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity, resulting in higher blood ethanol levels [45]. Furthermore, while the subgroup analysis indicated that US women with moderate alcohol intake had a 117 % greater RR, it might be unreliable because that the analysis only included one study.

In a meta-analysis, Castelnuovo et al. [46] indicated that low alcohol intake was associated with reduced risk of total mortality in both men and women, while heavy alcohol intake was associated with increased risk of total mortality. Costanzo et al. [47] suggested that low-to-moderate alcohol intake was significantly associated with a lower incidence of total mortality. The current study suggested that low-to-moderate alcohol might protect against total mortality risk in men, whereas there was no significant effect on the risk of total mortality in women. Furthermore, women with moderate alcohol intake had a 10 % greater RR for total mortality than men. The possible reasons for this were as follows: (1) there were multiple interrelations between alcohol intake and other risk factors of total mortality. In the current study, subgroup analysis showed that these associations differed if adjustments were made for physical activity or diabetes. However, we could not determine the effects of these potential confounding factors on the risk of total mortality because that very few studies were stratified using these confounders; (2) women with alcohol intake had higher blood ethanol levels, resulting in higher risk of liver disease, which significantly increases the risk of total mortality [45]; (3) concerns remained regarding the impact of the association between the pattern and duration of alcohol intake, such as binge drinking, and the risk of total mortality. Unfortunately, data on the pattern and duration of alcohol intake were rarely available in these studies, therefore, no conclusions could be made.

Previous meta-analyses suggested that increased alcohol intake was associated with a 23 % and 22 % reduction in risk of cardiac death for men and women, respectively [44]. Similarly, in the current study, no significant differences were observed in the relative risk ratios of cardiac death between those men and women who consumed alcohol. Women included in our study were mostly postmenopausal and had a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease; additionally, the association between alcohol and risk of cardiac death might appear to be reduced by regular drinking habits in women [48]. Furthermore, only three prospective observational studies reported the effect estimates of cardiac death for men and women separately. This conclusion might have not been accurate since smaller cohorts were included.

A previous meta-analysis conducted by Zhang et al. [49] illustrated the association between alcohol intake and the risk of stroke and stroke somatotypes, and suggested that low alcohol intake was associated with a reduced risk of stroke morbidity and mortality, whereas heavy alcohol intake was associated with an increased risk of total stroke. Furthermore, another important meta-analysis indicated that alcohol intake was associated with stroke risk; the study reported a 2 % risk increase and a 13 % risk reduction for men and women, respectively. In this study, there was no significant difference between men and women for the association between alcohol intake and the risk of stroke or ischemic stroke. Although women who consumed alcohol had a higher RR of stroke or ischemic stroke than men, this difference might be due to chance, as fewer studies were included, which might have resulted in less variation in the conclusions.

Two strengths of our study should be highlighted. First, only prospective studies were included, which should eliminate selection and recall bias that might be concerned of retrospective case–control studies. Second, the large sample size allowed us to quantitatively assess the gender difference for the association between alcohol intake and the risk of major cardiovascular outcomes or total mortality, and thus, our findings were potentially more robust than those of any individual study.

The limitations of our study were as follows: (1) the cut-off points for the alcohol intake categories differed among studies; (2) in a meta-analysis of published studies, publication bias was an inevitable problem; (3) the validity of self-reported alcohol intake during the follow-up period could be questioned; and (4) the analysis used pooled data (individual data were not available), which restricted us from performing a more detailed relevant analysis and obtaining more comprehensive results.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicated that women who were conferred by moderate alcohol intake had a significant 10 % increased risk of total mortality compared with men. Furthermore, stratified analyses suggested that women with heavy alcohol intake had a significantly increased RR risk of total mortality than male drinkers in multiple subpopulations. Future studies should focus on specific populations, especially for patients with chronic diseases in order to evaluate the secondary prevention of major cardiovascular outcomes.

References

Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med. 2004;38:613–9.

Yano K, Rhoads GG, Kagan A. Coffee, alcohol and risk of coronary heart disease among Japanese men living in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:405–9.

Langer RD, Criqui MH, Reed DM. Lipoproteins and blood pressure as biological pathways for effect of moderate alcohol consumption on coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1992;85:910–5.

Kitamura A, Iso H, Sankai T, Naito Y, Sato S, Kiyama M. et al. Alcohol intake and premature coronary heart disease in urban Japanese men. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:59–65.

JPHC Study Group. Alcohol consumption and risk of stroke among middle-age men: the JPHC Study Cohort I. Stroke. 2004;35:1124–9.

Donahue RP, Abbott RD, Reed DM, Yano K. Alcohol and Hemorrhagic Stroke: The Honolulu Heart Program. JAMA. 1986;255:2311–4.

Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of moderate alcohol consumption and the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:267–73.

Skov-Ettrup LS, Eliasen M, Ekholm O, Gronbaek M, Tolstrup JS. Binge drinking, drinking frequency, and risk of ischaemic heart disease: A population-based cohort study. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:880.

Harriss LR, English DR, Hopper JL, Powles J, Simpson JA, O’Dea K et al. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular mortality accounting for possible misclassification of intake: 11-year follow-up of the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Addiction. 2007;102:1574–85.

Maskarinec G, Meng L, Kolonel LN. Alcohol intake, body weight, and mortality in a multiethnic prospective cohort. Epidemiology. 1998;9:654–61.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Schlesselman JJ. Case–control studies. Design, conduct, analysis. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 1982.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa (ON): Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2009. Available: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm.

Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0. 2011; Available: www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Huxley RR, Woodward M. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Lancet. 2011;378:1297–305.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

Ades AE, Lu G, Higgins JP. The interpretation of random-effects meta analysis in decision models. Med Decis Making. 2005;25:646–54.

Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Analyzing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.0.1. Oxford, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. p. chap 9.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58.

Tobias A. Assessing the influence of a single study in meta-analysis. Stata Tech Bull. 1999;47:15–7.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101.

Djoussé L, Curtis Ellison R, Beiser A, Scaramucci A, D’Agostino RB, Wolf PA. Alcohol Consumption and Risk of Ischemic Stroke: The Framingham Study. Stroke. 2002;33:907–12.

Berberian KM, van Duijn CM, Hoes AW, Valkenburg HA, Hofman A. Alcohol and Mortality: Results from the EPOZ Follow-Up Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:587–93.

Sempos CT, Rehm J, Wu T, Crespo CJ, Trevisan M. Average Volume of Alcohol Consumption and All-Cause Mortality in African Americans: The NHEFS Cohort. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:88–92.

Britton A, Marmot M. Different measures of alcohol consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality: 11-year follow-up of the Whitehall II Cohort Study. Addiction. 2004;99:109–16.

Wellmann J, Heidrich J, Berger K, Doring A, Heuschmann PU, Keil U. Changes in alcohol intake and risk of coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality in the MONICA/KORA-Augsburg cohort 1987–97. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11:48.

Pedersen JØ, Heitmann BL, Schnohr P, Gronbaek M. The combined influence of leisure-time physical activity and weekly alcohol intake on fatal ischaemic heart disease and all-cause mortality. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:204–12.

Chiuve SE, Rexrode KM, Spiegelman D, Logroscino G, Manson JE, Rimm EB. Primary Prevention of Stroke by Healthy Lifestyle. Circulation. 2008;118:947–54.

Paganini-Hill A. Lifestyle Practices and Cardiovascular DiseaseMortality in the Elderly: The LeisureWorld Cohort Study. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:983764.

Hansen JL, Tolstrup JS, Jensen MK, Gronaek M, Tronneland A, Schmidt EB, et al. Alcohol intake and risk of acute coronary syndrome and mortality in men and women with and without hypertension. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26:439–47.

Tolstrup J, Jensen MK, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Mukamai KJ, Gronbaek M. Prospective study of alcohol drinking patterns and coronary heart disease in women and men. BMJ. 2006;332:1244–8.

Ikehara S, Iso H, Toyoshima H, Date C, Yamamoto A, Kikuchi S, et al. Alcohol Consumption and Mortality From Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease Among Japanese Men and Women: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Stroke. 2008;39:2936–42.

Yamada S, Koizumi A, Iso H, Wada Y, Watanabe Y, Date C, et al. Risk Factors for Fatal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Stroke. 2003;34:2781–7.

Lin Y, Kikuchi S, Tamakoshi A, Wakai K, Kawamura T, Iso H, et al. Alcohol Consumption and Mortality among Middle-aged and Elderly Japanese Men and Women. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:590–7.

Tikk K, Sookthai D, Monni S, Gross ML, Lichy C, Kloss M, et al. Primary Preventive Potential for Stroke by Avoidance of Major Lifestyle Risk Factors: The European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition-Heidelberg Cohort. Stroke. 2014;45:2041–6.

Drogan D, Sheldrick AJ, Schutze M, Knuppel S, Andersohn F, di Giuseppe R, et al. Alcohol Consumption, Genetic Variants in Alcohol Deydrogenases, and Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Prospective Study and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32176.

Arriola L, Martinez-Camblor P, Larranaga N, Basterretxea M, Amiano P, Moreno-Iribas C, et al. Alcohol intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in the Spanish EPIC cohort study. Heart. 2010;96:124–30.

Friesema IH, Zwietering PJ, Veenstra MY, Knottnerus JA, Garretsen HF, Kester AD, et al. The effect of alcohol intake on cardiovascular disease and mortality disappeared after takinglifetime drinking and covariates into account. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(4):645–51.

Friesema IH, Zwietering PJ, Veenstra MY,Knottnerus JA, Garretsen HF, et al. Alcohol intake and cardiovascular disease and mortality: the role of pre-existing disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:441–6.

Breslow RA, Graubard BI. Prospective Study of Alcohol Consumption in the United States: Quantity, Frequency, and Cause-Specific Mortality. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:513–21.

Mukamal KJ, Chen CM, Rao SR, Breslow RA. Alcohol Consumption and Cardiovascular Mortality among U.S. Adults, 1987–2002. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55(13): doi:10.1016.

Ronksley PE, Brien SE, Turner BJ, Mukamal KJ, Ghali WA. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d671.

Ely M, Hardy R, Longford NT, Wadsworth ME. Gender differences in the relationship between alcohol consumption and drink problems are largely accounted for by body water. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:894–902.

Castelnuovo AD, Costanzo S, Bagnardi V, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. et al. Alcohol Dosing and Total Mortality in Men and Women: An Updated Meta-analysis of 34 Prospective Studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2437–45.

Costanzo S, Di Castelnuovo A, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. Alcohol consumption and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1339–47.

Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Binge drinking and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;112:3839–45.

Zhang C, Qin YY, Chen Q, Jiang H, Chen XZ, Xu CL, et al. Alcohol intake and risk of stroke: a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cardio. 2014;174:669–77.

Funding

This study was funded by The Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2008ZX10002-007, 2008ZX10002-018, 2008ZX10002-025), The Leading Talents of Science in Shanghai 2010 (022), The Key Discipline Construction of Evidence-Based Public Health in Shanghai (12GWZX0602), The National Science Foundation of China (81373105).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Z-YH Conceived and designed the experiments. Z-YH, Z-C, L-F and H-J Performed the experiments. Z-YH and C-YW Analyzed the data. Z-YH Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. Z-YL, Z-YH and S-Q Wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the planning, execution, and interpretation of the submitted manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Yan-Ling Zheng Feng Lian and Qian Shi contributed equally to this work.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Adjustment factors of included studies. Figures S1. RR or RRR (female to male) of low alcohol intake and the risk of coronary disease. Figure S2. RR or RRR (female to male) of moderate alcohol intake and the risk of coronary disease. Figure S3. RR or RRR (female to male) of heavy alcohol intake and the risk of coronary disease. Figure S4. RR or RRR (female to male) of low alcohol intake and the risk of total mortality. Figure S5. RR or RRR (female to male) of moderate alcohol intake and the risk of total mortality. Figure S6. RR or RRR (female to male) of heavy alcohol intake and the risk of total mortality. Figure S7. RR or RRR (female to male) of low alcohol intake and the risk of ischemic stroke. Figure S8. RR or RRR (female to male) of low alcohol intake and the risk of cardiac death. Figure S9. RR or RRR (female to male) of low alcohol intake and the risk of stroke. Figure S10. RR or RRR (female to male) of moderate alcohol intake and the risk of cardiac death. Figure S11. RR or RRR (female to male) of moderate alcohol intake and the risk of stroke. Figure S12. RR or RRR (female to male) of moderate alcohol intake and the risk of ischemic stroke. Figure S13. RR or RRR (female to male) of heavy alcohol intake and the risk of cardiac death. Figure S14. RR or RRR (female to male) of heavy alcohol intake and the risk of stroke. Figure S15. RR or RRR (female to male) of heavy alcohol intake and the risk of ischemic stroke. Figure S16. Funnel plot of RRR (female to male) for low alcohol intake. Figure S17. Funnel plot of RRR (female to male) for moderate alcohol intake. Figure S18. Funnel plot of RRR (female to male) for heavy alcohol intake. (DOC 10344 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, YL., Lian, F., Shi, Q. et al. Alcohol intake and associated risk of major cardiovascular outcomes in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. BMC Public Health 15, 773 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2081-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2081-y