Abstract

Background

Escitalopram is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and one of the most commonly prescribed newer antidepressants (ADs) worldwide. We aimed to explore the efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of escitalopram in comparison with other ADs in the acute-phase treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD).

Methods

Medline/PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and Clinical Trials.gov were searched from inception to July 10, 2023. Trial databases of drug-approving agencies were hand-searched for published, unpublished and ongoing controlled trials. All randomized controlled trials comparing escitalopram against any other antidepressant for patients with MDD. Responders and remitters to treatment were calculated on an intention-to-treat basis. For dichotomous data, risk ratios (RRs) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous data were analyzed using standardized mean differences (with 95% CI) using the random effects model.

Results

A total of 30 studies were included in this meta‑analysis, among which sixteen trials compared escitalopram with another SSRI and 14 compared escitalopram with a newer AD. Escitalopram was shown to be significantly more effective than citalopram in achieving acute response (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.50—0.87). Escitalopram was also more effective than citalopram in terms of remission (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.30—0.93).

Conclusions

Escitalopram was superior to other ADs for the acute phase treatment of MDD in terms of efficacy, acceptability and tolerability. However, no significant difference was found between escitalopram and other ADs in early response or follow-up response to treatment of MDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a mood disorder which can lead to a persistent feeling of persistent sadness and loss of interest [1]. The lifetime prevalence of MDD is between 10–20% [2,3,4]. Recent estimates in 204 countries and territories found that the global prevalence and burden of MDD increased by 27.6% in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic [5]. MDD is the most serious disease in disability-adjusted life years (4.3%), and is estimated to be the leading cause of morbidity worldwide by 2030 if such trend continues [6]. The etiology of MDD is multifactorial, and social, cultural, genomic, aging and other underlying biological factors all play a role [7,8,9,10,11,12].

Both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments are effective for MDD [13], however, antidepressant drugs (ADs) remain the mainstay of treatment in primary and secondary medical institutions [14]. Amongst ADs, there are many different agents are available, including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and other newer ADs. The use of ADs is growing globally, especially in high-income countries [15], mainly due to the increasing consumption of SSRIs and newer ADs [16, 17]. SSRIs are generally better tolerated than TCAs, though the difference in efficacy is slight or negligible [18]. However, head-to-head comparisons have provided inverse findings. Duloxetine, for example, may have the edge over SSRIs in terms of efficacy [19, 20]. In addition, individual SSRIs and SNRIs may have varied outcomes [21]. SSRIs are first-line treatments for MDD [22]; however, these drugs work slowly and, in some patients, may not even work [23]. Escitalopram, one of SSRIs, is the representative of antidepressants currently used in terms of safety and efficacy [20, 23].

Recently, new randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of escitalopram in the treatment of MDD are pouring out, which were conducted in different circumstances [24,25,26], and the integration effects of these studies was ambiguous. Therefore, it is urgent to determine the true effect size of escitalopram for clinicians and clinical pharmacists. The aim of this present meta-analysis was to evaluate the efficacy of escitalopram in alleviating the acute symptoms of MDD, and to investigate the acceptability and adverse effects (AEs) of escitalopram in comparison with other ADs.

Methods

This meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [27]. A review protocol with search strategy was registered in the PROSPERO (CRD42022364229).

Search strategy

Electronic databases, including Medline/PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and Clinical Trials.gov, were searched to identify relevant studies from inception to July 10, 2023. No restrictions on language, publication status or gender were imposed. The reference lists of all included articles were also manually searched to identify any potential studies that might qualify.

Selection criteria

Only RCTs were included. Participants who were 18 years or older with a primary diagnosis of MDD were eligible. Studies prior to the 1990s may have used ICD-9, DSM-III/DSM-III-R or other diagnostic criteria. Later studies were more likely to have used criteria of DSM-IV or ICD-10. Studies using Research Diagnostic Criteria or Feighner criteria were included. However, ICD-9 criteria cannot be operationalized, so studies using ICD-9 were excluded. Studies in which no more than 20% of the participants might have bipolar depression were included.

Experimental intervention drug is escitalopram (as monotherapy). Comparator intervention drugs are other ADs for MDD, including TCAs, heterocyclic ADs, SSRIs, and newer ADs (SNRIs, MAOIs, newer agents, and non-conventional ADs such as herbal products). There were no restrictions on dose, frequency, intensity, and duration. Other types of psychotropic agents, such as anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics or mood-stabilizers, were excluded. Depressive patients with severe concomitant diseases, Axis I or II disorders were also excluded. Studies were excluded only if data were not provided at the time of meta-analysis.

The primary outcome was number of participants who responded to treatment, showing a reduction of at least 50% on the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) or Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), or any other depression scale, or score less than 2 on CGI-Improvement. The HAM-D was preferred to judge response when more than one criterion was provided. Secondary outcomes included number of participants who achieved remission, scores of change from baseline to the time point in question, acceptability and tolerability. The cut-off point for remission was preset to be score (1) less than 7 on the 17-item HAM-D or less than 8 for all the other longer versions of HAM-D, or (2) less than 12 on the MADRS, or (3) less than 2 on CGI-Severity. The HAM-D was preferred to judge remission when two or more criteria were provided. Change scores from baseline to the time point in question (early response, acute phase response, or follow-up response as defined above) were provided based on HAM-D, MADRS, or any other depression scale. We adopted a looser form of intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, namely all the participants with more than one post-baseline measurement were represented by their final observations. Acceptability was assessed by total dropout rate, dropout rates due to inefficacy, and dropout rates due to AEs. Tolerability was assessed by total number of patients experiencing at least one AEs, total number of participants experiencing Deaths and suicide. In order to avoid missing any relatively rare yet important AEs, in the data extraction phase, we collected all AEs data reported in the literature and discussed methods for post-hoc summarization.

All titles and abstracts were checked by two reviewers independently (JY and XS) to determine if they met the rough inclusion criteria. All the studies rated as possible candidates by either of the two reviewers were added to the preliminary list. All the full-text articles in the preliminary list were then inspected independently by two reviewers (CW or XL) to determine whether they met the strict inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion, or adjudication of a third reviewer (MM).

Data extraction

Data were collected by two reviewers (JY and CW) using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The extracted data included: author, year of publication, sample size, age, study duration, dose, diagnostic criteria, outcome measures, response criteria, remission criteria rate, overall discontinuation rate, discontinuation rate due to AEs. At the end of the data extraction phase, all key extracted data were reviewed and quality checked by the same two reviewers. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion at first; and then brought to a third author (MM) for resolution, as required.

Risk of bias assessment

Two authors (JY and YC) independently used the Cochrane “Risk of bias” (ROB 2.0) tool to assess the methodological quality of the included trials [28].

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using RevMan 5.4 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020). To evaluate heterogeneity, we used the I2 statistic (with I2 > 50% indicating significant heterogeneity) [29] and Cochran’s Q P value (with P < 0.05 indicating significant heterogeneity). Risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was described by categorical data. Standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI was used for continuous outcomes.

Publication bias was evaluated by visual inspection of funnel plot [30]. We performed subgroup analyses to determine whether the results were influenced by the different types of control groups (other SSRIs or newer ADs). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the synthesized results by excluding studies whose dropout rate was greater than 20%.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

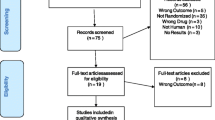

The preliminary search yielded 109 references of potentially eligible studies. After exclusion of studies that were not relevant (mainly for reviews were or non-randomized studies), a total of 30 RCTs were included in this present review (Fig. 1) [24,25,26, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

The basic characteristics for all included studies are displayed in Table 1. In the presentation of the following analyses, a post-hoc decision was made to present all SSRIs (with sub-totals) together in one group, and SNRIs and newer ADs (without sub-totals) together in another group. Sixteen trials (53.3%) compared escitalopram with another SSRI and fourteen (46.7%) compared escitalopram with a newer AD (venlafaxine, bupropion, duloxetine, agomelatine, vilazodone and desvenlafaxine). Neither trials comparing escitalopram with TCAs or MAOIs. Among the total 30 included studies, 28 studies were multicenter, randomized, double-blind trials, the other 2 was randomized, open-label trial. Of all the 30 studies, 17 had an overall high risk of bias, 11 had some concerns of bias, and 2 had a low risk (Figure S1).

The effects of interventions in efficacy, acceptability and tolerability are presented below. The results are reported by comparison (dividing SSRIs from newer ADs). AEs are only reported when statistically significant.

Number of patients who responded to treatment

Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was a statistically significant difference with escitalopram being more effective than other SSRIs (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.95, I2 = 33%; 14 studies, 4111 participants) (Fig. 2). There was a statistically significant difference with escitalopram being more effective than newer ADs (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.97, I2 = 43%; 11 studies, 3663 participants) (Fig. 3).

Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

There was no statistically significant difference with escitalopram being more effective than other SSRIs (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.11) (Figure S2) or newer ADs (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.08) (Figure S3).

Follow-up response (16 to 24 weeks)

There was no statistically significant difference between escitalopram and other SSRIs (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.05, I2 = 0%) (Figure S4). And there was no statistically significant difference between escitalopram and newer ADs (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.19) (Figure S5).

Number of patients who achieved remission

Acute phase treatment (6 to 12 weeks)

There was statistically significant difference between escitalopram being more effective than other SSRIs (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.99, I2 = 69%) (Fig. 4), however, there was no statistically significant difference with escitalopram being more effective than newer ADs (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.01, I2 = 36%) (Figure S6).

Follow-up remission (16 to 24 weeks)

There was no statistically significant difference between escitalopram being more effective than other SSRIs (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.27) (Figure S7) or newer ADs (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.10) (Figure S8).

Mean change from baseline (6 to 12 weeks)

Escitalopram was found to be more efficacious than other SSRIs in reduction of depressive symptoms (SMD -0.13, 95% CI -0.19 to -0.06, I2 = 34%) (Figure S9) or newer ADs (SMD -0.41, 95% CI -0.81 to -0.02, I2 = 97%) (Figure S10).

Tolerability-Total number of patients experiencing at least one side effect

There were statistically significant differences between escitalopram and other SSRIs in terms of tolerability (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.89 to 0.97, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 5). However, there were no statistically significant differences between escitalopram and newer ADs in terms of tolerability (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.01, I2 = 29%) (Figure S11).

Sensitivity analysis

The trials whose dropout rates were greater than 20% were excluded in the sensitivity analysis. Referring to other SSRIs, a dropout rate greater than 20% was found for three studies comparing escitalopram with citalopram [37, 49, 50], one with fluoxetine [40] and one with paroxetine [36]. Among newer ADs, a dropout rate greater than 20% was found for all the three studies comparing escitalopram with bupropion [31, 32, 52], two with duloxetine [48, 55], two with agomelatine [26, 39], one with desvenlafaxine [53], one with vilazodone [25], and one with venlafaxine [35]. Three studies had only one arm reporting a dropout rate greater than 20% [38, 42, 43]. Therefore, sensitivity analysis was conducted only for the comparisons between escitalopram and other SSRIs.

Results from the sensitivity analyses remained in favor of escitalopram, not only when studies whose dropout rate was greater than 20% in both arms were ruled out (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.97, I2 = 68%; 7 studies, 1893 participants; Figure S12), but also when studies whose dropout rate was greater than 20% in only one arm were additionally ruled out (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.98, I2 = 71%; 4 studies, 1062 participants; Figure S13). Therefore, results from these sensitivity analyses did not materially change the main findings, suggesting that the pooled analyses were robust.

Publication bias

Funnel plot of the studies enrolled in the meta-analysis demonstrated no significant asymmetry by visual inspection, therefore, the outcome of failure to respond at 6–12 weeks (escitalopram vs. other SSRIs) was not affected by publication bias (Figure S14).

Discussion

Thirty studies were included in this review. Escitalopram was superior to other SSRIs or newer ADs for the acute phase treatment of MDD in terms of efficacy (citalopram, fluoxetine, desvenlafaxine and duloxetine) and acceptability (Paroxetine and duloxetine). A quarter of the included trials used citalopram as the comparator and only a few trials per comparison were found for most of the remaining ADs (with the exception of duloxetine, fluoxetine, paroxetine and bupropion), which limits the power of this study to detect moderate but clinically meaningful differences between the drugs. The randomized evidence collected in the datasets for this review was sufficient to detect differences in early response to treatment (after two weeks of intervention). However, checking the data reported in the studies included in this meta-analysis, the question on comparative efficacy of early onset response has not been resolved and remains a controversial issue.

To the best of our knowledge, our work is the most comprehensive review to date of the comparative efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of escitalopram and other ADs for the treatment of MDD. The sample size in our study was larger than that of similar systematic reviews comparing an AD versus other ADs [58, 59]. Escitalopram is a relatively new compound and the quality of psychiatric trials may have improved over the past few years. By using a broader scope and advanced statistical methods, our findings provide more certainty about results than previous reviews which assessed similar research questions [20, 60]. Although these studies also focused on RCTs to assess the comparative safety and efficacy of drugs, we employed meta-analyses which enabled us to use a more comprehensive evidence base including head-to-head trials.

It has long been argued that placebo-controlled trials are required to adequately demonstrate the efficacy of newer ADs [61], however, receiving placebo in RCTs increased the chances of dropout and decreased the absolute response of participants to active ADs [62]. In the case of ADs, it may be more appropriate to conduct trials using an active comparator (chosen from the most effective and better-tolerated treatments available) [63]. Therefore, in this review, we included only head-to-head trials comparing between escitalopram and other active treatments. Because the literature search was comprehensive, it might be impossible that some studies had not been identified.

Our study demonstrated that escitalopram was superior to other ADs for the acute phase treatment of MDD in terms of efficacy, acceptability and tolerability. The mechanism action of escitalopram to improve MDD especially in the acute phase may be characterized by the increased subcortical network-ventral attention network connectivity [64], lower plasma kynurenine levels and resting-state regional activity in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [65].

There are some limitations in this review. At First, although the sample size was larger, most studies still do not report adequate information on randomization and allocation concealment. For example, outcomes that were clearly relevant to patients and clinicians, in particular, patients' and their caregivers' attitudes to interventions, their ability to resume work and normal social functioning, were not reported in the enrolled studies. Furthermore, information on randomization and allocation concealment was occasionally lacking, which may be due to reporting in the text than real defects in study design. At last, the reports of the outcomes in the included studies were often unclear or incomplete and the figures used for the analyses were not easy to understand. And sometimes there were some inconsistencies between published data and unpublished data on the websites of pharmaceutical industries. In order to make up for these limitations, we evaluated the risk of bias in the results of trials, and preferred to report meta-analyses restricted to trials with low risk of bias [66,67,68].

In terms of AEs profile, we found that different ADs showed different tolerability profiles, which is an important issue from a clinical point of view, and the outcomes of this study are consistent with previous findings [69, 70]. However, a full description of tolerability profile of drugs cannot rely solely on randomized evidence [71, 72]. In addition, AEs were inconsistently reported in the included studies in our review, which hampers cross-study comparisons. The reporting of AEs needs to be standardized, and more consideration should be given to patients' subjective experience of medication. During the evidence-based decision-making process, clinicians should consider and inform patients of different AEs profiles among ADs, therefore, the issue on tolerability is clinically important. However, it has been shown that RCTs might not be the most effective tool for identifying possible causal relationship between ADs and even severe adverse events (SAEs) [73]. This applies to class-related AE, but might also apply to each specific compound. The more information that is pooled together in a systematic review and meta-analysis, the more precise and accurate is the estimate [74]. We are also aware of the possibility that a number of RCTs comparing escitalopram with other ADs are currently underway [75]. With more reliable and longer-term studies, the real impact and burden of the newer ADs on treated patients in terms of tolerability will be known.

Moreover, clinicians should take dosage and duration into consideration when administering drug therapy. In this review, nearly all studies used dosages and durations within the therapeutic range. Sixteen studies used a flexible-dose regimen and the remaining fourteen used a fixed-dose one. Among the included studies, there was no evidence of imbalance in terms of dosage, duration, or disease severity in favor of the investigational drug.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that escitalopram appears to be suitable as first-line antidepressant treatment for moderate to severe MDD. Escitalopram was superior to other ADs for the acute phase treatment of MDD in terms of efficacy, acceptability and tolerability. However, there is insufficient evidence to detect a difference between escitalopram and other ADs in early response or follow-up response to treatment of MDD. Sponsorship bias may lead to overestimation of treatment effects; therefore, results reported for comparative efficacy should be treated with caution.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse effect

- AD:

-

Antidepressant

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HAM-D:

-

Hamilton Depression Scale

- ITT:

-

Intention-to-treat

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- MAOI:

-

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor

- MADRS:

-

Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- ROB:

-

Risk of bias

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- SSRI:

-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- SNRI:

-

Serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor

- SAE:

-

Severe adverse event

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- TCA:

-

Tricyclic antidepressant

References

Espinoza RT, Kellner CH. Electroconvulsive Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(7):667–72.

Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, Ho CS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. Prevalence of Depression in the Community from 30 Countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2861.

Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Stohl M, et al. Epidemiology of Adult DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder and Its Specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiat. 2018;75(4):336–46.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Prevalence and correlates of major depressive disorder among a national sample of middle-aged and older adults in India. Aging Ment Health. 2023;27(1):81–6.

Santomauro D, Herrera A, Shadid J, Zheng P, Ashbaugh C, Pigott D, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700–12.

Bathla M, Anjum S, Singh M, Panchal S, Singh GP. A 12-week Comparative Prospective Open-label Randomized Controlled Study in Depression Patients Treated with Vilazodone and Escitalopram in a Tertiary Care Hospital in North India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2018;40(1):80–5.

Pham TH, Gardier AM. Fast-acting antidepressant activity of ketamine: highlights on brain serotonin, glutamate, and GABA neurotransmission in preclinical studies. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;199:58–90.

Namkung H, Lee BJ, Sawa A. Causal Inference on Pathophysiological Mediators in Psychiatry. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2018;83:17–23.

Lax E. DNA Methylation as a Therapeutic and Diagnostic Target in Major Depressive Disorder. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:759052.

Cui L, Wang Y, Cao L, Wu Z, Peng D, Chen J, et al. Age of onset for major depressive disorder and its association with symptomatology. J Affect Disord. 2023;320:682–90.

Wang X, Xia J, Wang W, Lu J, Liu Q, Fan J, et al. Disrupted functional connectivity of the cerebellum with default mode and frontoparietal networks in young adults with major depressive disorder. Psychiat Res. 2023;324:115192.

Tanifuji T, Okazaki S, Otsuka I, Mouri K, Horai T, Shindo R, et al. Epigenetic clock analysis reveals increased plasma cystatin C levels based on DNA methylation in major depressive disorder. Psychiat Res. 2023;322:115103.

Garcia A, Yáñez AM, Bennasar-Veny M, Navarro C, Salva J, Ibarra O, et al. Efficacy of an adjuvant non-face-to-face multimodal lifestyle modification program for patients with treatment-resistant major depression: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiat Res. 2023;319:114975.

Shao S, Sun B, Sun H. Clinical efficacy of Vortioxetine and escitalopram in the treatment of depression. Pak J Med Sci. 2022;38(5):1389–94.

Brauer R, Alfageh B, Blais JE, Chan EW, Chui CSL, Hayes JF, et al. Psychotropic medicine consumption in 65 countries and regions, 2008–19: a longitudinal study. Lancet Psychiat. 2021;8(12):1071–82.

Yu Z, Zhang J, Zheng Y, Yu L. Trends in Antidepressant Use and Expenditure in Six Major Cities in China From 2013 to 2018. Front Psychiat. 2020;11:551.

Cebron Lipovec N, Anderlic A, Locatelli I. General antidepressants prescribing trends 2009–2018 in Slovenia: a cross-sectional retrospective database study. Int J Psychiat Clin Pract. 2022;26(4):401–5.

Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Direct comparison of tricyclic and serotonin-reuptake inhibitor antidepressants in randomized head-to-head trials in acute major depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31(9):1184–9.

Harada E, Schacht A, Koyama T, Marangell LB, Tsuji T, Escobar R. Efficacy comparison of duloxetine and SSRIs at doses approved in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:115–23.

Cipriani A, Santilli C, Furukawa TA, Signoretti A, Nakagawa A, McGuire H, et al. Escitalopram versus other antidepressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4(2):CD006532.

Cipriani A, Barbui C, Brambilla P, Furukawa TA, Hotopf M, Geddes JR. Are all antidepressants really the same? The case of fluoxetine: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiat. 2006;67(6):850–64.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357–66.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Focus. 2018;16(4):420–9.

Kishi T, Matsuda Y, Matsunaga S, Moriwaki M, Otake Y, Akamatsu K, et al. Escitalopram versus paroxetine controlled release in major depressive disorder: a randomized trial. Neuropsych Dis Treat. 2017;13:117–25.

Kudyar P, Gupta BM, Khajuria V, Banal R. Comparison of efficacy and safety of escitalopram and vilazodone in major depressive disorder. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2018;8(8):1147–52.

Udristoiu T, Dehelean P, Nuss P, Raba V, Picarel-Blanchot F, de Bodinat C. Early effect on general interest, and short-term antidepressant efficacy and safety of agomelatine (25–50mg/day) and escitalopram (10–20mg/day) in outpatients with Major Depressive Disorder. A 12-week randomised double-blind comparative study. J Affect Dis. 2016;199:6–12.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Clayton (AK130926) www.gsk.com/research/clinical/clinicalreg.html

Clayton (AK130927) http://www.gsk.com/research/clinical/clinicalreg.html

Alexopoulos G, Gordon J. Zhang DHolper L. A placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram and sertraline in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;29:S87.

Baldwin DS, Cooper JA, Huusom AK, Hindmarch I. A double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, flexible-dose study to evaluate the tolerability, efficacy and effects of treatment discontinuation with escitalopram and paroxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharm. 2006;21(3):159–69.

Bielski RJ, Ventura D, Chang CC. A double-blind comparison of escitalopram and venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiat. 2004;65(9):1190–6.

Boulenger JP, Huusom AK, Florea I, Baekdal T, Sarchiapone M. A comparative study of the efficacy of long-term treatment with escitalopram and paroxetine in severely depressed patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(7):1331–41.

Burke WJ, Gergel I, Bose A. Fixed-dose trial of the single isomer SSRI escitalopram in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiat. 2002;63(4):331–6.

Colonna L, Andersen HF, Reines EH. A randomized, double-blind, 24-week study of escitalopram (10 mg/day) versus citalopram (20 mg/day) in primary care patients with major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(10):1659–68.

Corruble E, de Bodinat C, Belaïdi C, Goodwin GM. Efficacy of agomelatine and escitalopram on depression, subjective sleep and emotional experiences in patients with major depressive disorder: a 24-wk randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Int J Neuropsychoph. 2013;16(10):2219–34.

Kennedy SH, Anderson HF, Lam RW. A pooled analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine. Poster presented at the American Psychiatric Association. In: 2005.

Kadam RL, Sontakke SD, Tiple P, Motghare VM, Bajait CS, Kalikar MV. Comparative evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of vilazodone, escitalopram, and amitriptyline in patients of major depressive disorder: a randomized, parallel, open-label clinical study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52(2):79–85.

Kasper S, de Swart H, Andersen HF. Escitalopram in the Treatment of Depressed Elderly Patients. Am J Geriat Psychiat. 2005;13(10):884–91.

Khan A, Bose A, Alexopoulos GS, Gommoll C, Li D, Gandhi C. Double-blind comparison of escitalopram and duloxetine in the acute treatment of major depressive disorder. Clin Drug Investig. 2007;27(7):481–92.

Lepola UM, Loft H, Reines EH. Escitalopram (10–20 mg/day) is effective and well tolerated in a placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18(4):211–7.

Mao PX, Tang YL, Jiang F, Shu L, Gu X, Li M, et al. Escitalopram in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, fixed-dose, parallel trial in a Chinese population. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(1):46–54.

Montgomery SA, Huusom AK, Bothmer J. A randomised study comparing escitalopram with venlafaxine XR in primary care patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;50(1):57–64.

Moore N, Verdoux H, Fantino B. Prospective, multicentre, randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy of escitalopram versus citalopram in outpatient treatment of major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharm. 2005;20(3):131–7.

Nierenberg AA, Greist JH, Mallinckrodt CH, Prakash A, Sambunaris A, Tollefson GD, et al. Duloxetine versus escitalopram and placebo in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: onset of antidepressant action, a non-inferiority study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(2):401–16.

Ou JJ, Xun GL, Wu RR, Li LH, Fang MS, Zhang HG, et al. Efficacy and safety of escitalopram versus citalopram in major depressive disorder: a 6-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose study. Psychopharmacology. 2011;213(2–3):639–46.

Flexible-dose comparison of the safety and eficacy of Lu 26–054 (escitalopram), citalopram, and placebo in the treatment of major depressive disorder www.forestclinicaltrials.com

Double-blind comparison of the efects of Lu 26–054 (escitalopram) and fluoxetine on sleep in depressed patients www.forestclinicaltrials.com

Fixed-dose comparison of escitalopram combination in adult patients with major depressive disorder www.forestclinicaltrials.com

Soares CN, Thase ME, Clayton A, Guico-Pabia CJ, Focht K, Jiang Q, et al. Desvenlafaxine and escitalopram for the treatment of postmenopausal women with major depressive disorder. Menopause. 2010;17(4):700–11.

Ventura D, Armstrong EP, Skrepnek GH, Haim EM. Escitalopram versus sertraline in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(2):245–50.

Wade A, Gembert K, Florea I. A comparative study of the efficacy of acute and continuation treatment with escitalopram versus duloxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(7):1605–14.

Yevtushenko VY, Belous AI, Yevtushenko YG, Gusinin SE, Buzik OJ, Agibalova TV. Efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram versus citalopram in major depressive disorder: a 6-week, multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study in adult outpatients. Clin Ther. 2007;29(11):2319–32.

Kumar PNS, Suresh R, Menon V. An Open-Label Rater-Blinded Randomized Trial of Vilazodone versus Escitalopram in Major Depression. Indian J Psychol Med. 2023;45(1):19–25.

Brignone M, Diamand F, Painchault C, Takyar S. Efficacy and tolerability of switching therapy to vortioxetine versus other antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(2):351–66.

Bauer M, Tharmanathan P, Volz HP, Moeller HJ, Freemantle N. The effect of venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants and placebo in the treatment of major depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiat Clin Neurosci. 2009;259(3):172–85.

Maneeton B, Maneeton N, Likhitsathian S, Woottiluk P, Wiriyacosol P, Boonyanaruthee V, et al. Escitalopram vs duloxetine in acute treatment of major depressive disorder: meta-analysis and systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1953–61.

Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Placebo in clinical trials for depression: complexity and necessity. JAMA. 2002;287(14):1853–4.

Salanti G, Chaimani A, Furukawa TA, Higgins JPT, Ogawa Y, Cipriani A, et al. Impact of placebo arms on outcomes in antidepressant trials: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(5):1454–64.

Geddes JR, Cipriani A. Time to abandon placebo control in pivotal phase III trials? World Psychiat. 2015;14(3):306–7.

Zhang S, Zhou J, Cui J, Zhang Z, Liu R, Feng Y, et al. Effects of 12-week escitalopram treatment on resting-state functional connectivity of large-scale brain networks in major depressive disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2023;44(6):2572–84.

Kamishikiryo T, Okada G, Itai E, Masuda Y, Yokoyama S, Takamura M, et al. Left DLPFC activity is associated with plasma kynurenine levels and can predict treatment response to escitalopram in major depressive disorder. Psychiat Clin Neurosci. 2022;76(8):367–76.

Vanhala A, Lehto AR, Maksimow A, Torkki P, Kivivuori SM. Classifying outcomes in secondary and tertiary care clinical quality registries-an organizational case study with the COMET taxonomy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):806.

Lin YH, Sahker E, Shinohara K, Horinouchi N, Ito M, Lelliott M, et al. Assessment of blinding in randomized controlled trials of antidepressants for depressive disorders 2000–2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;50:101505.

Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, Schulz KF, Jüni P, Altman DG, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2008;336(7644):601–5.

Arango C, Buitelaar JK, Fegert JM, Olivier V, Pénélaud PF, Marx U, et al. Safety and efficacy of agomelatine in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder receiving psychosocial counselling: a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial in nine countries. Lancet Psychiat. 2022;9(2):113–24.

Inoue T, Sasai K, Kitagawa T, Nishimura A, Inada I. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of vortioxetine in Japanese patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiat Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(2):140–8.

Etminan M, Takkouche B, Isorna FC, Samii A. Risk of ischaemic stroke in people with migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2005;330(7482):63.

Jiang W, Liang GH, Li JA, Yu P, Dong M. Migraine and the risk of dementia: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(6):1237–46.

de Abajo FJ, García-Rodríguez LA. Risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine therapy: interaction with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and effect of acid-suppressing agents. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2008;65(7):795–803.

Cumpston MS, McKenzie JE, Welch VA, Brennan SE. Strengthening systematic reviews in public health: guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd edition. J Public Health (Oxf). 2022;44(4):e588–e92.

Yokoi Y, Nakagawa A, Yoshimura N, Furukawa TA, Mimura M, Iwanami A, et al. Acceptability of escitalopram versus duloxetine in outpatients with depression who did not respond to initial second-generation antidepressants: study protocol for a randomized, parallel-group, non-inferiority trial. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2019;39(4):262–72.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Mrs. Naiqin Wang for search strategy.

Funding

This work was funded by Science and Technology Department of Henan Province (grant number 112102310306) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 21605042).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Juntao Yin, Mingsan Miao, and Xuhong Lin conceived and designed the study. Juntao Yin and Chaoyang Wang selected the articles and extracted data. Xuhong Lin and Chaoyang Wang were responsible for statistical analysis. Juntao Yin and Xiaoyong Song wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Mingsan Miao provided advice at different stages. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Risk of bias summary. Figure S2. Failure to respond (at 1-4 weeks): Escitalopram versus other SSRIs. Figure S3. Failure to respond (at 1-4 weeks): Escitalopram versus newer ADs. Figure S4. Failure to respond (at 16-24 weeks): Escitalopram versus other SSRIs. Figure S5. Failure to respond (at 16-24 weeks): Escitalopram versus newer ADs. Figure S6. Failure to remission at endpoint (6-12 weeks): Escitalopram versus newer ADs. Figure S7. Failure to remission (at 16-24 weeks): Escitalopram versus other SSRIs. Figure S8. Failure to remission (at 16-24 weeks): Escitalopram versus newer ADs. Figure S9. Standardized mean difference at endpoint (6-12 weeks): Escitalopram versus other SSRIs. Figure S10. Standardized mean difference at endpoint (6-12 weeks): Escitalopram versus newer ADs. Figure S11. Subjects with at least one TEAE: Escitalopram versus newer ADs. Figure S12. Excluding trials whose dropout rate was greater than 20%: Escitalopram versus other SSRIs (dropout rate greater than 20% in both arms). Figure S13. Excluding trials whose dropout rate was greater than 20%: Escitalopram versus other SSRIs (dropout rate greater than 20% in only one arm). Figure S14. Funnel plot of comparison: Failure to respond at endpoint (6-12 weeks): Escitalopram versus other SSRIs.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, J., Song, X., Wang, C. et al. Escitalopram versus other antidepressive agents for major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 23, 876 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05382-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05382-8