Abstract

Background

Because of COVID-19 pandemic, families across the world are experiencing new stressors that threaten their health, and economic well-being. Such a stress may jeopardize parents-children relationship. We aim to investigate the magnitude of child physical maltreatment (CPM) by parents in Egypt during the COVID-19 pandemic, to relate it to parents’ stress, and to identify other potential risk factors.

Methods

This cross-sectional study assessed parent-reported CPM and their personal experience of stress, depression, and anxiety among a sample of Egyptian parents using an electronic survey. It included sociodemographic data, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), and the Child physical maltreatment scale (CPMS). We also briefly assessed COVID-19 -related data.

Results

Out of 404 respondents, (62.9%) and (32.9%) reported performing minor and severe CPM toward their children during the past 3 months, respectively. The age of youngest child, and anxiety score were significantly correlated with both minor and severe forms of CPM. While number of children, and online education system ratings were only significantly correlated with severe CPM. Parental definition of CPM was significantly correlated to minor CPM, but not to severe CPM.

Conclusions

CPM by parents is not uncommon in Egypt, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings highlight the importance of regular support and intervention that help parents learn parenting skills and the use of non-violent child disciplining methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic poses new challenges to every family across the world, given the novelty and uncertainty concerning this disease [11]. Variable models of prevention have been adopted in different countries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Preventive measures in Egypt included suspension of education (from March 15th until October 16th, 2020), and closure of Mosques and churches. There was partial lockdown with “stay-at-home” orders [9, 22].

Such a global crisis and its percussions, including increased economic stress, unemployment, lockdown, social isolation, physical and mental health concerns, and the shift to home-schooling, may contribute to increased stress among parents [21, 24, 39]. When feeling overwhelmed by the crisis, and when individuals’ resources are insufficient to cope with stressors, parents experience high levels of stress. They may vent these negative emotions through improper behaviours, such as physical or verbal abuse, particularly in families with history of domestic violence or child maltreatment [17, 43]. For example, parents having burnout reported more conflicts with their partners and higher levels of child abuse and neglect [31]. An interventional research even demonstrated that child abuse and neglect could be reduced by targeting levels of parental stress [10].

Amid the COVID-19 crises, increasing reports of child physical maltreatment (CPM) during periods of quarantine and lockdowns emerged [17]. In contrast to these reports, rates of child maltreatment officially reported decreased during the pandemic, which could be attributed to social isolation, and reduced in-person contact with teachers, doctors, child protective services and other professionals, who mainly report such incidents [13, 24]. Despite the underestimated number of maltreatment cases, public health organizations emphasized the increased risk for child maltreatment, especially among families that were abusive prior to the pandemic [39, 43].

Unfortunately, limited studies tackling CPM have been done in Egypt, due to the lack of population-based statistics, and unreliable official records [4]. Researchers often resort to parent or child reports to measure CPM incidence, despite evidence that parents usually underreport maltreatment of their children [34]. Still, it provides a better estimate of CPM occurrence,up to 70 times higher than the estimates derived from official reports [40].

Hard as it is, such a problem is also challenging to study in the Arab countries, and in Egypt, due to the cultural reluctance to report CPM [6]. In the Arab world, research about CPM is scarce, and available ones show it is common and underreported [4].

El-Defrawi, Atef, Ragab & Sobhy [18] study (done on a total of 672 Egyptian parents) reported that they tend to use force in the form of beating to discipline children, particularly when the child shows disruptive behaviour or delinquency. And that such practices increase in severity, and it may even be fatal in low socio-economic families, with lower educational level of parents.

To date, very few studies addressed CPM and parents’ stress in low & middle-income countries [11, 13, 32]. The current study aims, firstly, to estimate the magnitude of CPM in an Egyptian convenient sample during the COVID-19 pandemic. Secondly, to investigate the association between CPM and parental psycho-social stress (stress, anxiety, depression). We hypothesize a robust relation between CPM to parents’ stress. This study can help generate a base of knowledge for monitoring and evaluating CPM and family violence in low & middle-income countries.

Methods

A cross-sectional research design was employed in this study. The study group comprised a total of 404 parents recruited (using convenient sampling) by disseminating the electronic survey link through social media (Facebook groups of parents of different school types). The recruitment statement specified that respondents should be Egyptian parents living in Egypt; there were no listed exclusion criteria.

Due to the lack of awareness of CPM, the social stigma attached to CPM in the Egyptian culture, and the possible unease of participants to report such incidents [4], we resorted to conduct this study using an anonymous online survey. The online survey was open for completion from January 2021 to March 2021. Completion of the survey was entirely voluntary and anonymous. The study protocol was approved by the Ain Shams university ethical committee with the number FMASU R 128/2021. An informed consent statement was obtained from participants.

Assessment

Demographics of the of 404 participants’ were assessed, including age, gender, education level, marital status, perceived family income(high/average/low), residence, and number and age of children. COVID-19 stressors were briefly assessed using investigator developed questions, for fear of being a potential confounding factor. Parents were asked if they tested positive for COVID-19 or knew someone who had COVID-19 infection. Using a scale from (0–10), parents were asked to indicate their level of worry of the COVID-19 pandemic, and to rate how stressful was the social isolation at home, and the shift to online education system.

Moreover, parents were asked one question, if they-themselves- were subjected to physical maltreatment as children (never/ rarely/ sometimes/ often/ very often).

Participants completed 2 sets of scales, namely, the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21) [27] and the Child physical maltreatment scale (CPMS) [28].

The DASS-21 tool consists of 3 self-report scales that assess depression, anxiety, and stress during the past 7 days on a four-point scale between zero and three with higher scores indicating severity. Scores of statements under the same emotional category (seven statements each) were summed and multiplied in two. Out of 42, the cut-off values for mild to moderate depression, anxiety, and stress were 10, 8, and 15, and for severe to very severe were 21, 15, and 26, respectively [12, 27]. The Cronbach’s α of the DASS-21 scale in the current sample was 0.939. the arabic version of DASS-21 tool was used [5].

Child physical maltreatment (CPM) was evaluated using the CPM scale [28].

CPM was assessed based on items used in various published studies (e.g., [7, 14, 37, 42]. The scale included 7 items:

-

Pinched, shook, pushed or shoved a child

-

Hit child’s hand, back, arm or leg with hand

-

Hit child’s buttocks with hand

-

Hit child’s buttocks with an object

-

Hit child’s face or head with hand

-

Kicked a child with a foot or hit with a fist

-

Hit elsewhere (not buttocks) with an object

The first three items are defined as minor CPM. The last four items are classified as severe CPM [28]. The Cronbach’s α of the 7-item scale in the current sample was 0.743.

Frequency of CPM

The scale asked parents how often they performed the behaviours in these items towards their children during the past 3 months. The response categories included never, 1–2 times, 3–5 times, 6–10 times and > 10 times. The midpoints of response categories of the scale were used to define the frequency scores during the past 3 months, that is, “0” for “never,” “1.5” for “1–2 times,” “4” for “3–5 times,” “8” for “6–10 times,” and “15” for “more than 10 times.” [37].

Respondents’ definition of CPM

After each item, the respondent was asked whether he/she believed that the behaviour was an abusive behaviour. Responses were categorized by a 3-point measure, on which “1” indicated “yes,” “2” indicated “unsure,” and “3” indicated “no.” Higher scores reflected low awareness of CPM.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done on a personal computer using IBM© SPSS© Statistics version 26 (IBM© Corp., Armonk, NY).

Data were described in the form of number and percentage, and mean SD. Correlations among numerical variables were tested using Pearson correlation test (r). P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Multiple linear regression analysis was used to assess predictors of the frequency of different forms of CPM. The confidence interval was set to 95% and the margin of error accepted was set to 5%. So, the p-value was considered significant at the level of < 0.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

This is a cross sectional study of Egyptian parents reporting Child Physical Maltreatment (CPM). A total of 404 participants were enrolled in study (377 mothers and 27 fathers), with mean age of (37.4 ± 5.7) years. Most participants reported middle family income (73.5%), and almost all lived in urban location. Participants were mostly married and had a higher education degree. Almost third of parents reported being abused physically themselves as children (Table1).

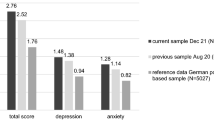

According to DASS-21 cut-off scores, participants’ responses were divided to 3 degrees; normal, mild to moderate, and severe to very severe. According to participants’ responses, 40.1%, 39.6% and 48.8% showed mild to moderate depression, anxiety, and stress, respectively. 31.4%, 47% and 30.2% of the participants reported severe to extremely severe symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression, respectively (Fig. 1).

Participants’ definition, and frequency of CPM

The mean frequencies of occurrence of minor and major CPM in past 3 months were 4.2 ± 6.6 and 1.6 ± 4.2 times, respectively (Table 1). The most common forms of CPM were ‘Hitting a child’s hand, back, arm or leg with hand’ (46.3%), followed by ‘Pinching, shaking, pushing or shoving a child’ (46%) and then ‘Hitting a child elsewhere (not buttocks) with an object’ (15.8%) (supplement table S1). It is important to mention that (22.5%) refused to mention frequency of one or more form of CPM.

As shown in Table 2, the minor CPM definition score (denoting minor CPM definition by parents) was significantly negatively correlated with the frequency of minor CPM in past 3 months. However, parental definition of severe CPM was not significantly correlated with severe CPM frequency.

Participants’ definitions of CPM are demonstrated in Fig. 2. Out of all parents, 5.4%, 19.8% and 38.6% defined the three items of minor CPM (Pinched, shook, pushed or shoved a child- Hit child’s hand, back, arm or leg with hand- Hit child’s buttocks with hand) as not abusive, respectively. As for severe CPM, 35.9%, 29.2%, 32.4% and 30.9% viewed the four items (Hit child’s buttocks with an object- Hit child’s face or head with hand-Kicked a child with a foot or hit with a fist-Hit elsewhere (not buttocks) with an object) as not abusive, respectively.

Regarding minor CPM, Table 2 shows that the age of parents, age of the youngest child, were negatively correlated with minor CPM frequency. While minor CPM frequency was positively correlated with all three depression, anxiety, and stress scores.

On the other hand, major CPM frequency was negatively correlated with the age of youngest child, number of children, and online education ratings. And it was only positively correlated with the anxiety score.

Multiple regression analysis

The variables with a significant correlation with frequency of both forms of CPM (in past 3 months) were included in the multiple regression analysis (Table 3). It showed that the age of youngest child, minor CPM definition score, and anxiety score stood out to be of significance as predictors of minor CPM frequency in past 3 months. On the other hand, regarding severe CPM frequency; the age of youngest child, number of children, online school education ratings, and anxiety score remained significant.

Discussion

There is concern that the COVID-19 pandemic may carry hidden threats to children’s safety worldwide [24]. Given the increased contact between family members amid lockdown together with an economic crisis, this may have created the ideal conditions for an increase in CPM [34]. Such a rise will possibly be underestimated given the difficulty to track its incidence during the pandemic.

We found that the parental self-reported CPM (during past 3 months) in the study sample was common, with 62.9% and 32.9% of parents reported minor and severe CPM towards their children, respectively. It is hard to determine if it is because of COVID-19 crises or not, due to the lack of pre-pandemic data. Regarding parental stress, only parents’ anxiety was correlated to both minor and severe CPM frequency in past 3 months, in contrast depression and stress were not of significance after multiple regression analysis. Parental definition of CPM was predictive for minor CPM frequency only, but not severe CPM frequency. In addition, younger age of children was negatively correlated with both minor and severe CPM frequency. While a greater number of children was only positively correlated with severe forms of CPM.

In one of the few Egyptian studies underwent during the pandemic, 90.5% of children were subjected to violent discipline, and 43.2% encountered severe physical punishment [1]. These rates were higher than that in our study, which could be attributed to the use of different tools, and the time of sampling.

To the best of our knowledge, few studies addressed CPM in Low- and Middle-Income Countries or the Arab world. For example, Maker, Shah, and Agha [29] estimated parent–child physical violence to be 78% in a Latina sample, 73% in South Asian and Middle Eastern samples, and 65% in an East Asian sample. Two Chinese studies also reported comparable figures to our results,in Ma et al. [28] parental self-reported CPM was 42.7% for minor CPM and 21.6% for severe CPM. Similarly, Tang [38] showed prevalence rates between 46 and 52.6% for minor CPM. And in agreement with our results, CPM was more frequently inflicted on younger as compared to older children.

However, a recent Iranian study, showed much lower rates that that in our sample, with 27% of elementary school children reported being physical abused at home [33]. And, in contrast to our findings, there was insignificant effect of child’s age on child abuse. This variation may be explained by the different age groups of the sample, or cultural variation.

Our findings were, however, comparable to previous pre-pandemic Egyptian and regional population-based studies, where pre-pandemic studies reported rates of CPM between 55 and 72% in their samples [4, 19, 44]. However, a previous pre-pandemic study of severe CPM in Egypt showed much less rates than ours (7.6%) versus (32.9%) in our sample [2]. This discrepancy may be explained by the different age groups included in the samples, as well as contextual factors.

Though the age of parents was positively correlated with minor CPM frequency, it was not of significance after controlling for other factors in multiple regression analysis. This came in contrast to other studies, associating physical means of punishment with younger age of parents [3, 15]. This is quite understandable, since younger parents may have less parenting abilities, experience, and knowledge to manage their children, and have more stresses due to limited financial resources. However, in agreement with our findings, [35] found no consistency of parental age as a risk factor for maltreatment.

Respondents’ definition of CPM

In this study, parental definition of CPM significantly impacted the frequency of minor CPM, but not severe CPM. This came in contrast to some studies showing CPM to be associated with parents’ approving of physical discipline [8, 16]. However, one Chinese study had similar results to ours demonstrating that parental definition of CPM had a significant impact on the frequency of minor CPM, but not on severe CPM [28]. Why that was significant for minor, but not severe CPM frequency, warrants further study. However, this finding denotes that frequency of severe CPM mostly occurred regardless of parents’ definition of CPM, i.e., whether parents thought it was an abusive act or not. This aligns with the idea that all parents can become abusive under certain circumstances [21].

In the current sample, parents who regarded items of minor CPM as non-abusive ranged from 5.4% to 38.6%, and those who viewed major CPM as non-abusive ranged from 29.2% to 35.9%. Attitudes toward physical punishment of children as a form of discipline may be affected greatly by unawareness and cultural norms [28]. According to Egyptian traditional culture, some CPM behaviors, especially the minor CPM behaviors, may not be considered abusive, because corporal punishment is somewhat accepted as a disciplining approach [36]. Our results support this observation, given that almost third of the parents in this study reported being abused physically themselves as children.

In concordance with our results, a study underwent in Saudi Arabia reported that around 34% of the participants reported a history of CPM [3]. In fact, many researchers have found that parents’s own rearing history contributes to the way they practice parenting [23]. For instance, many child protective services involve parents that have been abused as children. Such early traumatic experiences can adversely impact their caregiving behavior and increase risk of the intergenerational transmission of child abuse [41]. We could not determine whether parental past history of CPM could explain the high rates of CPM in the sample in the current study design. Yet, identifying such high-risk parents and providing them with training programs could be effective in the prevention of CPM.

CPM and COVID -19 variables

Perceived COVID-19 worry, and social isolation were not related to the frequency of any form of CPM. While online education parents’ ratings had significant correlation with severe CPM. In agreement with our results, Brown et al. [11] found that the cumulative stressors from COVID-19 did not significantly relate to increased risk of CPM potential in their sample. Although stress, in general, is strongly associated with CPM, however stressors specific to COVID-19 may not intensify CPM risk. These results need replication using standardized tools.

CPM and Parents’ stress (using DASS-21)

Out of all participants, 31.4%, 47% and 30.2% reported severe to extremely severe symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression, respectively. These results are consistent with prior research showing that during the COVID-19 pandemic nearly a third of adults reported clinically meaningful symptoms of anxiety and depression [11, 25]. In another Italian study, 17% of their sample experienced significant parenting-related exhaustion in COVID-19 pandemic [30]. El‑Zoghby, Soltan, & Salama [20] Egyptian study of COVID-19 impact on mental health, showed that (41.4%) of their sample suffered a severe impact.

Regarding relation to CPM, we found that after multiple regression, only parents’ anxiety scores stood out to be of significance in predicting both minor and severe CPM frequency.

In agreement to our results, Brown et al., [11] and Lawson et al. [24] studies demonstrated that parental anxiety was a significant predictor of CPM during the pandemic. One Egyptian study showed that there was a strong association between psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on parents and them practicing violence against their children [1].

Limitations

Although the CPM rates are apparently common in our study, they are mostly minimum estimates of the actual figures. Several important limitations should be borne in mind when interpreting these results. First, the observational nature of the present study and the lack of pre-pandemic data to compare with, make it difficult to draw causal inferences. Moreover, convenience samples lack generalizability. Second, the current study only studied physical maltreatment, we did not assess emotional abuse, neglect, nor sexual abuse. Third, some parents may refrain from reporting CPM behaviors because of shame. Fourth, using an online survey may have caused a sort of selection bias as it may only be restricted to those who had smart devices and internet access. This is displayed in the fact that most participants were of the middle class and very few were from a low socio-economic class. This may have underestimated the gravity of the situation. Finally, self-selection bias may exist if the non-respondents were either too abusive to their children or not at all abusive and therefore not interested in this survey.

Despite limitations, this study has important clinical implications such as;

There are unmet needs by the child welfare system in Egypt even before the COVID-19 pandemic. This could be overcome, by providing multiple points of contact to reach parents and children (e.g., primary health care, public schools, and religious institutions). Finally, parents’ stress is a potentially modifiable risk factor contributing to CPM. Parents’ training programs can be an effective solution [26].

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available upon request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- CPM:

-

Child Physical Maltreatment

- DASS-21:

-

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales

- CPMS:

-

Child physical maltreatment scale

References

Abo Kresha SA, Abdelkreem E, Ali RAE. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and related isolation measures on violence against children in Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2021;96(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42506-021-00071-4.

Afifi ZE, El-Lawindi MI, Ahmed SA, Basily WW. Adolescent abuse in a community sample in Beni Suef, Egypt: prevalence and risk factors. East Mediterr Health J. 2003;9(5–6):1003–18 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16450531 .

Al Dosari MN, Ferwana M, Abdulmajeed I, Aldossari KK, Al-Zahrani JM. Parents’ perceptions about child abuse and their impact on physical and emotional child abuse: a study from primary health care centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Fam Community Med. 2017;24(2):79–85. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.205110.

Al-Eissa MA, AlBuhairan FS, Qayad M, Saleheen H, Runyan D, Almuneef M. Determining child maltreatment incidence in Saudi Arabia using the ICAST-CH: a pilot study. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;42:174–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.08.016.

Ali AM, Ahmed A, Sharaf A, Kawakami N, Abdeldayem SM, Green J. The Arabic Version of The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21: Cumulative scaling and discriminant-validation testing. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;30:56–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2017.07.018.

Al-Moosa A, Al-Shaiji J, Al-Fadhli A, Al-Bayed K, Adib SM. Pediatricians’ knowledge, attitudes and experience regarding child maltreatment in Kuwait. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(10):1161–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.009.

Alyahri A, Goodman R. Harsh corporal punishment of Yemeni children: Occurrence, type and associations. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(8):766–73.

Ateah CA, Durrant JE. Maternal use of physical punishment in response to child misbehavior: implications for child abuse prevention. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(2):169–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.010.

Biltagy M. (2021). How did covid-19 pandemic impact education in Egypt?, EMEA Policy Paper. https://euromed-economists.org/download/how-did-covid-19-pandemic-impacteducation-in-egypt/#flipbook-df_rand1325002951/1/.

Brianda ME, Roskam I, Gross JJ, Franssen A, Kapala F, Gerard F, Mikolajczak M. (2020). Treating parental burnout: Impact of two treatment modalities on burnout symptoms, emotions, hair cortisol, and parental neglect and violence. Psychother Psychosomatics. 1, 3. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506354.

Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Pena S, Watamura SE, Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt 2):104699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699.

Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(1):79-89.

Campbell AM. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci Int Rep. 2020;2:100089–100089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089.

Chen JQ. Study on physical abuse by parents and the influencing factors among pupils. Chin J School Health. 2006;27:756–7.

Connelly CD, Straus MA. Mother’s age and risk for physical abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16(5):709–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(92)90107-3.

Crouch JL, Behl LE. Relationships among parental beliefs in corporal punishment, reported stress, and physical child abuse potential. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(3):413–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00256-8.

Cuartas J. Heightened risk of child maltreatment amid the COVID-19 pandemic can exacerbate mental health problems for the next generation. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020;12(S1):S195–6. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000597.

El-Defrawi MH, Atef A, Ragab L, Sobhy SA. Parent-child interactions and child abuse in rural and urban population samples in Ismailia, Port-Said and Suez Governorates. Egypt J Psychiatry. 1997;20:283–96.

Elsaied H, Alsehly A. A study of child physical abuse. Egypt J Psychiatry. 2017;38(2):120–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/1110-1105.209674.

El-Zoghby SM, Soltan EM, Salama HM. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and social support among adult Egyptians. J Community Health. 2020;45(4):689–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00853-5.

Griffith, A. K. (2020). Parental Burnout and Child Maltreatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Fam Viol, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00172-2

Hassany M, AbdelRazek W, Asem N, AbdAllah M, Zaid H. Estimation of COVID-19 burden in Egypt. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30319-4.

Khamis V. Child psychological maltreatment in Palestinian families. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(8):1047–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00157-5.

Lawson M, Piel MH, Simon M. Child Maltreatment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Consequences of Parental Job Loss on Psychological and Physical Abuse Towards Children. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt 2):104709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709.

Lee, S. J., & Ward, K. P. (2020). Mental health, relationships, and coping during the coronavirus pandemic [Research brief]. https://bit.ly/2O84btj

Letarte M-J, Normandeau S, Allard J. Effectiveness of a parent training program “Incredible Years” in a child protection service. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(4):253–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.06.003.

Lovibond S, Lovibond P. Manual for the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales. 2nd ed. Sydney: Psychology Foundation; 1995.

Ma Y, Chen J, Xiao W, Wang F, Zhang M. Parents’ self-reporting of child physical maltreatment in Yuncheng City. China Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(8):592–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.04.006.

Maker AH, Shah PV, Agha Z. Child physical abuse: prevalence, characteristics, predictors, and beliefs about parent-child violence in south Asian, Middle Eastern, East Asian and Latina women in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2005;11:1406–28.

Marchetti D, Fontanesi L, Mazza C, Di Giandomenico S, Roma P, Verrocchio MC. Parenting-Related Exhaustion During the Italian COVID-19 Lockdown. J Pediatric Psychol. 2020;45:jsaa093. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa093.

Mikolajczak M, Gross JJ, Roskam I. Parental burnout: what is it, and why does it matter? Clin Psychol Sci. 2019;7(6):1319–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619858430.

Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2020;75(5):631–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660.

Rafaiee R, Mohseni F, Akbarian N. Prevalence of Child Abuse and Correlations with Family Factors Among Elementary School-aged Children. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. 2021;10(2):e108823. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijhrba.108823.

Rodriguez CM, Lee SJ, Ward KP, Pu DF. The perfect storm: hidden risk of child maltreatment during the Covid-19 pandemic. Child Maltreat. 2020;26(2):139–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559520982066.

Schumacher JA, Slep AM, Heyman RE. Risk factors for child neglect. Aggression Violent Behav. 2001;6:231–54.

Seleem MA, Amer RA. Parenting discipline styles and child psychopathology in a clinical sample of Egyptian children in the Nile Delta region. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2020;27(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-020-00063-8.

Straus MA, Stewart JH. Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1999;2(2):55–70.

Tang CS. Corporal punishment and physical maltreatment against children: a community study on Chinese parents in Hong Kong. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30(8):893–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.02.012.

The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action. (2020). Technical Note:Protection of Children during the Coronavirus Pandemic (v.2). United Nations International Children’s Fund. https://alliancecpha.org/en/COVD19.

Theodore A, Chang JJ, Runyan D. Measuring the risk of physical neglect in a population-based sample. Child Maltreat. 2007;12(1):96–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559506296904.

Widom CS, Czaja SJ, DuMont KA. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: real or detection bias? Science. 2015;347:1480–5.

Wong WCW, Leung PWS, Tang CSK, Chen WQ, Lee A, Ling DC. To unfold a hidden epidemic: Prevalence of child maltreatment and its health implications among high school students in Guangzhou China. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33(7):441–50.

Wu Q, Xu Y. Parenting stress and risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a family stress theory-informed perspective. Dev Child Welfare. 2020;2(3):180–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516103220967937.

Zolotor AJ, Runyan DK, Dunne MP, Jain D, Peturs HR, Ramirez C, Isaeva O. ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool Children’s Version (ICAST-C): Instrument development and multi-national pilot testing. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(11):833–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.004.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M S A and Z M E; study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript. M A H; made substantial contributions to conception and design of the present study and data interpretation. M M G, interpretation of results. N Y S, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ain Shams University Hospital Ethics Committee, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent statement was obtained from participants before participation in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table(S1). CPM 7-items frequency during past 3 months reported by the studied participating parents. Figures (S1). Curve estimation ofsignificant predictors of minor and severe CPM frequency (in multipleregression).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdeen, M.S., Hashim, M.A., Ghanem, M.M. et al. Parents’ self-reporting of Child Physical Maltreatment (CPM) in a low-middle-income country. BMC Psychiatry 23, 506 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04947-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04947-x