Abstract

Background

Aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), its associated correlates and relations with clinical and behavioural problems among children and adolescents with HIV/AIDS (CA-HIV) attending five HIV clinics in central and South Western Uganda.

Methods

This study used a quantitative design that involved a random sample of 1339 children and adolescents with HIV and their caregivers. The Participants completed an extensive battery of measures including a standardized DSM-5 referenced rating scale, the parent version (5–18 years) of the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-5 (CASI-5). Using logistic regression, we estimated the prevalence of ADHD and presentations, correlates and its impact on negative clinical and behavioural factors.

Results

The overall prevalence of ADHD was 6% (n = 81; 95%CI, 4.8–7.5%). The predominantly inattentive presentation was the most common (3.7%) whereas the combined presentation was the least prevalent (0.7%). Several correlates were associated with ADHD: socio-demographic (age, sex and socio-economic status); caregiver (caregiver psychological distress and marginally, caregiver educational attainment); child’s psychosocial environment (quality of child-caregiver relationship, history of physical abuse and marginally, orphanhood); and HIV illness parameters (marginally, CD4 counts). ADHD was associated with poor academic performance, school disciplinary problems and early onset of sexual intercourse.

Conclusions

ADHD impacts the lives of many CA-HIV and is associated with poorer academic performance and earlier onset of sexual intercourse. There is an urgent need to integrate the delivery of mental health services into routine clinical care for CA-HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Joint United Nations Programme on AIDS estimates that 88% of the global 3.3 million children and adolescents living with HIV (CA-HIV) reside in Sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Most of these CA-HIV who were perinatally infected with HIV are at risk of developing emotional and behavioural problems [2]. Although many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa including Uganda [3] have adopted the WHO policy recommendation [4] that calls for the integration of mental health services into HIV care, most HIV clinics on the continent have yet to implement them [5].

In Uganda, prevalence of HIV in the general population has stabilised around 7.4% [6], with highest rates in the Central Region (10.6%) and the lowest in Mid-Eastern Region (4.1%). Prevalence is higher among women (8.3%) than men (6.1%); 3.7% of young women and men between 15 and 24 years of age are HIV-positive [3]. There is fairly compelling evidence that HIV contributes to neurocognitive impairment and possibly neuropsychiatric illnesses [7,8,9,10]. CA-HIV experience relatively high rates of psychopathology [11,12,13,14,15] that could arise from the direct and indirect effects of HIV including the psychosocial problems of family disruptions; poor social support; and a high burden of negative life events, stigma, poverty and chronic ill health [16] and the burden of long-term treatment with antiretroviral therapy (ART) [17].

Previous studies have found that ADHD is one of the most common psychiatric disorders among CA-HIV (Scharko, as cited in Mellins and Malee, 2013) [2]. However, little is known about ADHD among CA-HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. Most of what is known comes from two studies [15, 18] conducted in Kenya and South Africa. The Kenyan study reported a prevalence of 12.2% as based on both parent and youth report [18], whereas the South African study found rates of 88% and 17% based on parent and teacher ratings, respectively [15]. The rates of ADHD reported in the Kenyan and South African studies differed significantly possibly due to differences in the assessment instruments used. Whereas the Kenyan study used the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID) [18], a DSM IV based psychiatric assessment tool that undertakes both a symptom count and assessment of functional impairment, the South African study used the Swanson, Nolan and Pelham rating scale [15], a DSM IV-based psychiatric assessment tool that only assesses symptom count. To date, no study has established the prevalence of ADHD among CA-HIV in Uganda.

Although it is widely recognized that ADHD is highly heritable [19], a wide range of variables are associated with symptom severity in CA-HIV [2], and these include impaired social and academic functioning [2, 17, 20,21,22,23,24], which can negatively affect quality of life. However, relatively little is known about child, family, and illness characteristics associated with severity of ADHD among CA-HIV in East Africa or their implications for functional outcomes. The primary objectives of the present study were to (a) document the prevalence of ADHD among a large sample of CA-HIV attending rural and urban HIV clinics in Uganda, (b) characterize the relation of ADHD severity with a wide range of commonly studied clinical correlates, and (c) examine the relation of ADHD with important indices of academic and social functioning. We were particularly interested in ADHD because it is associated with emotional and behavioural dysregulation thus increasing the risk of impaired decision making, poor impulse control, risky sexual behaviour, and aggression among CA-HIV [2].

Methods

Participants

The study comprised a random sample of 1339 child/adolescent-caregiver dyads from the five HIV clinics in rural (Masaka) and urban (Kampala) Uganda. To be eligible for the study, CA-HIV had to be between 5 and 11 and 12–17 years of age, respectively, and caregivers had to be at least 17 years of age. Both CA-HIV and caregivers had to speak English or Luganda (the local language spoken in the study areas) and plan to reside in the study area for the subsequent 12 months. Exclusion criteria were concurrent enrollment in another study (which applied to only one site), need of immediate medical attention, and unable to understand the study’s assessment instruments.

Measures

The assessment battery comprised standardised, locally translated psychosocial instruments [16, 17, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Study variables reported in this paper are described in Additional file 1: Table S1 arranged according to the conceptual framework. ADHD was established using a clinically practical, DSM-5-referenced, behaviour rating scale, the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-5 (CASI-5) [34], which was previously used to study ADHD in CA-HIV in the United States [35, 36]. CASI-5 items can be scored in several different ways, and in the present study we used the symptom count cut-off score. Symptom count cut-off score indicates whether child/adolescent has the prerequisite number of symptoms necessary for a DSM-5 diagnosis. The CASI-5 also provides an algorithm that we used to generate the different ADHD presentations.

Procedures

To obtain the required sample of 268 study participants per study site, research assistants identified potential participants from the patient register. Those who met eligibility criteria were then invited to enroll into the study. This procedure was repeated each clinic day until the required sample size of each site was attained. About 2% of eligible participants were not included owing to a number of reasons including participation in another ongoing study, inability to contact the caregiver to obtain consent, or refusal to give consent by the caregiver.

The study protocol was administered by trained psychiatric nurses and psychiatric clinical officers supervised by a clinical psychologist (RM) and overseen by a psychiatrist (EK). Interviews were conducted in two parts, each part lasting 30 min with a tea break in between. Psychosocial assessments used for the first time in Ugandan, which included the CASI-5 [34], underwent a translation and local adaptation process described in a separate paper [37]. Briefly, this entailed separate forward and back translations by teams of mental health professionals and lay people conversant in both English and Luganda; a consensus workshop of translation teams to derive the versions with the most acceptable face validity; and administration to CA-HIV/caregiver dyads to refine the terminology in order to enhance clarity.

Statistical analyses

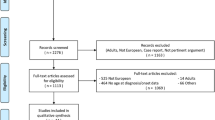

Prevalence of the three ADHD presentations (predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, and combined) as well as any ADHD was estimated with 95% confidence intervals by age-group and gender. Clinical correlates for ADHD were determined by fitting multiple logistic regression models, using the approach recommended by Victora et al. [38]. These variables were divided into four groups: socio-demographic, caregiver, child’s psychosocial environment, and CA-HIV health status (see Fig. 1). First, an initial prediction model was selected based only on socio-demographic variables; study site (as a design variable), sex and age were included in all models as a priori confounders, while other socio-demographic variables were excluded from the model if they were not significant at the 10% level. Caregiver characteristics were then added to the socio-demographic model that had been selected, and those variables that were not statistically significant at the 10% level were removed. Next, psychosocial environment variables were then added to the socio-demographic and caregiver model, and variables that were not statistically significant at the 10% level were removed. Analyses were conducted separately for children and adolescents as some variables were obtained for adolescents but not on children. Then, variables related to the health status of CA-HIV were added to the previous model, and those that were not significant at the 10% level were removed. Finally, any of the initial variables that were no longer significant at the 15% level were omitted. This liberal p-value for potential confounders is advocated by some experts, e.g., Royston et al. [1].

We then examined the association of ADHD with several functional outcomes: poor academic performance at school, poor social functioning at school (experienced problems at school), number of visits to the health unit in the past month, hospital admissions in the last month, non-adherence to HIV treatment and risky sexual behaviour (onset of sexual intercourse) (see Additional file 1 for a detailed description of these variables). For each of these outcomes, the association with ADHD was assessed by fitting a logistic regression model, adjusting for study site (as a design variable), sex, age and educational level. For visit to a health unit and hospital admission, adjustment was also made for current CD4 count, whereas for adherence, adjustment was made for whether or not the CA-HIV was receiving ART (which determined how non-adherence was measured). Associations were assessed separately for each ADHD presentation.

To adjust for multiple testing we followed the suggestion of Bender and Lange [37] and regarded the study as an exploratory study in which significance tests were used for descriptive purposes rather than for decision making. Thus, findings should be viewed as preliminary, and further work is required to carry out confirmatory studies. This approach is supported by Vittinghoff et al. [39] who noted that in an exploratory analysis, it is not clear how many comparisons should be corrected for, but stressed the need for cautious interpretation of any findings.

Ethical considerations

The study obtained ethical approvals from the Uganda Virus Research Institute’s Research and Ethics Committee, the Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology. Participants voluntarily provided consent (caregivers)/assent (CA-HIV). Participants found to have a psychiatric disorder were provided with psycho-education and referred to their local mental health departments.

Result

Characteristics of study participants

Briefly, 64% of CA-HIV were between 5 and 11 years, and 36% were between 12 and 17 years (see Additional file 2 for a detailed description of the study sample). The urban and rural study sites contributed equally. There slightly were more females (52%) than males (48%). With regard to HIV illness parameters, 88% had CD4 counts equal or greater than 350 cells/μL, and most (95%) of the participants were receiving ART.

Prevalence of ADHD

Six percent (6.0%; 95% CI, 4.8–7.5%) of CA-HIV met CASI-5 symptom count criteria for at least one ADHD presentation (Table 1). For specific presentations, rates were 3.7% for the predominantly inattentive (I) presentation, 1.6% for the predominantly hyperactive-impulsive (HI) presentation, and 0.7% for the combined (C) presentation. Among children the most frequent ADHD presentation was ADHD-I (3.0%), followed by ADHD-HI (2.0%) with ADHD-C (0.6%) being the least frequent. Among adolescents ADHD-I (4.8%) was also the most frequent, but both ADHD-HI (1.0%) and ADHD-C (1.0%) were second. The rank order of presentations was the same for both males and females.

Clinical correlates of ADHD inattentive

Variables associated with ADHD-I symptom count cut-off score were increasing age (aOR of 1.14 per 1 year increase in age, p = 0.004), socio-economic status (aOR of 1.91 per unit increase in SES, p = 0.009), caregiver psychological distress scores (aOR of 1.11 per unit increase in psychological distress scores of caregiver, p = 0.004), and quality of child-caregiver relationship (aOR of 1.34 per unit deterioration in quality of the child-caregiver relationship scores, p < 0.0001) (see Additional file 3). Higher caregiver educational status (p = 0.08) and CD4 counts (p = 0.06) approached significance.

Clinical correlates of ADHD hyperactive-impulsive

Variables associated with ADHD-HI symptom scores were increasing caregiver psychological distress scores (aOR of 1.11 per unit increase in psychological distress scores of caregiver, p = 0.02), quality of child-caregiver relationship (aOR of 1.20 per unit deterioration in quality of the child-caregiver relationship scores, p = 0.09), and only assessed among adolescents, having ever been beaten (aOR = 5.0, p = 0.02) (see Additional file 3).

Clinical correlates of ADHD combined

Variables associated with ADHD-C symptom scores were caregiver psychological distress (aOR of 1.16 per unit increase in psychological distress scores of caregiver, p = 0.04) (see Additional file 3). Orphanhood was marginally significant (p = 0.05), with rates highest for those CA-HIV with no living parent compared to those who had at least one living parent (aOR = 11.03, p = 0.05).

Clinical correlates of any ADHD

Variables associated with having any ADHD presentation were increasing socio-economic status (aOR of 1.84 per unit increase in SES, p = 0.004), caregiver psychological distress scores (aOR of 1.11 per unit increase in psychological distress scores of caregiver, p = 0.001), quality of child-caregiver relationship (aOR of 1.32 per unit deterioration in quality of the child-caregiver relationship score, p < 0.0001) (see Additional file 3). Caregiver educational level was marginally significant (p = 0.06).

Association between ADHD presentation and outcome

ADHD-I presentation and having any ADHD were associated with poor academic performance (see Table 2), and having any ADHD was associated with having problems at school. ADHD-I and having any ADHD were marginally associated with early initiation of sexual intercourse (p = 0.07). None of the ADHD presentations were associated with non-adherence to HIV treatment, number of hospital visits, or number of hospital admissions.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of ADHD among CA-HIV in Uganda and associations of ADHD with commonly studied mental health clinical correlates and social, academic and clinical functioning. The prevalence of caregiver-rated ADHD was 6%, which is similar to caregiver-reported CASI ADHD rates for non-HIV, community-based samples in the United States [40, 41]. When we adopted a more clinically oriented criterion for any ADHD based on both symptom count cut-off score and impairment cut-off score, the prevalence of any ADHD was 2.2%, which underscores the importance of considering criteria for defining ADHD when comparing results across studies. With regard to CA-HIV, a study conducted in the United States that used CASI [17, 35] symptom count cut-off scores found that 16% met criteria for ADHD according to caregiver ratings [36]. These findings seem to suggest that the rate of ADHD in the United States study is much higher than that in Uganda, at least among HIV populations. However, Gadow et al. [17] also found the prevalence of ADHD among uninfected youth in the United States from HIV-affected families was similar to CA-HIV (12.6%), and rates for both groups (infected and affected) were higher than comparable rates for population-based samples [40, 41]. The authors noted that one plausible explanation for these differences between infected/affected youth and population-based samples in the United States is the much higher percentage of minority youth among the former and the well-established relation of minority status with mental health concerns, clinical correlates, and less than optimal health care. To this we would add that socio-cultural differences in symptom grading among caregivers in more industrialised Western countries as compared to the more agrarian Ugandan environment (where the caregivers are expected to have a tolerance for psychiatric symptomatology as compared to their Western counterparts) may also contribute to disparate rates of ADHD.

In Uganda the most common ADHD presentation was ADHD-I, followed by ADHD-HI with ADHD-C being the least prevalent. This relative distribution of ADHD presentations was similar for children and adolescents with the exception that rates of ADHD-HI and ADHD-C were identical among adolescents. In the United States study conducted by Gadow and colleagues [17], among their younger cohort (6–12 years old) both ADHD-I and ADHD-HI were tied in first place. Among their older cohort (13–18 years old), ADHD-I was more common than ADHD-HI and ADHD-C, rates for which were identical. Conversely, the South African study by Zeegers and colleagues [15] found that caregiver ratings indicated ADHD-HI and ADHD-C were the most and least common, respectively, but teacher assessments of the same sample indicated ADHD-C was the most frequent presentation with ADHD-I and ADHD-HI both coming in second.

In our Uganda study, several clinical correlates were associated with the different ADHD presentations. Increasing age was associated with increased risk for ADHD-I, which is consistent with the findings from review of literature from nine studies conducted in Africa [42] and is likely explained by the increasing demands school curricula as youth grow older. We observed an increase in the risk of ADHD-I with increasing socio-economic status whereas previous studies of non-HIV samples conducted in the West have reported just the opposite [35, 37]. A possible explanation for our Uganda finding is that more affluent families are better able to pay school fees, and the school is arguably the primary setting in which ADHD-I symptoms are most problematic. In addition, higher socio-economic status is associated with caregiver educational attainment and greater sensitivity to their child’s academic success. Consistent with this interpretation, there was a marginally significant association between increasing caregiver educational status and rates of ADHD-I.

Increasing caregiver psychological distress was associated with higher rates of all ADHD presentations. Similar results have previously been reported by others both among an HIV [2] and a non-HIV [21] population in the West. Possible explanations suggested by others include heritability of ADHD (or any other mental health problems), stressful family and social environments associated with ADHD (or any other mental health problems), and the erosion of parenting capacities which often accompany a parent with HIV or mental illness [2, 21, 43]. In support of the latter, we found that deteriorating quality of the child-caregiver relationship (communication style and emotional reaction between the child and caregiver) was associated with all three ADHD presentations, which is consistent with the findings of others for both HIV [43] and non-HIV [44] samples. Suffering physical abuse (i.e., having ever been beaten) was associated with a fivefold increased risk of ADHD: HI in our adolescent-age sample, which is in accord with the extant literature [44]. It has been suggested that ADHD symptoms may illicit feelings of hostility in the caregiver causing them to use aversive behaviour management strategies with CA-HIV [44].

Additional variables associated with ADHD were orphanhood and CD4 counts. Orphanhood, which not surprisingly was highest among those who reported loss of both parents, was marginally associated with ADHD-C. Previous studies among HIV populations have reported the association between orphanhood and youths’ mental health [45, 46]. Decreasing CD4 counts were marginally associated with increase in the odds of ADHD-I, and prior studies undertaken in the United States report similar findings [2, 10, 35, 36, 43, 47, 48].

ADHD can have a substantial impact on school functioning and is associated with poor exam performance, grade retention, and failure to graduate from secondary school [49]. Cognitive deficits that may interfere with academic performance have commonly been reported among CA-HIV [22, 35, 50]. In our Ugandan sample, we found that any ADHD presentation and ADHD-I specifically were associated with poor academic performance. In addition, having any ADHD presentation was associated with problems at school, which is in accord with prior research involving CA-HIV [2, 35].

Early onset of sexual intercourse (only assessed among adolescents) was marginally associated (p = 0.07) with a two- to threefold increase of having any ADHD or ADHD-I (aORs of 2.93 and 3.43, respectively). Studies conducted elsewhere have reported a positive association between ADHD and risky sexual behaviour [21, 23, 35], which may have important implications for disease transmission. Although others have reported that among CA-HIV, co-occurring ADHD is associated with poorer adherence to HIV treatment, number of hospital visits, and hospital admissions [43, 50], this was not the case in our study.

This study has several strengths to include an exceptionally large sample of CA-HIV, comprehensive assessment battery, and cross-cultural orientation, there are also limitations. Because our analyses are cross-sectional, we cannot comment on the casual directions, but these will be addressed in future publications about the longitudinal component of the CHAKA study. Since ADHD symptoms are influenced by environmental variables and therefore different informants can disagree about symptom severity [51], our prevalence rates for ADHD in Uganda should be considered conservative estimates as we did not obtain CASI-5 ratings from our sample’s school teachers. Because we do not have a comparable sample of seronegative youth from the same geographic areas and environment, it is not possible to know whether relations between ADHD and putative mental health factors and functional outcomes are influenced by HIV status. This does not, however, detract from the clinical implications of our findings for CA-HIV. By design, the present study focused on CA-HIV living in Uganda, and owing to considerable cultural variation in East Africa, our results may not generalize to other countries in the region.

Conclusions

In summary, approximately 6% of CA-HIV living in Uganda met DSM-5 symptom count criteria for ADHD. Clinical ccorrelates of ADHD were reported for all domains (general socio-demographic, caregiver, psychosocial environmental and HIV illness). ADHD among CA-HIV was associated with poorer academic performance, school disciplinary problems, and earlier age of onset of sexual intercourse, all of which may have important implications for clinical management, quality of life, long-term outcome and possible disease transmission. Moving forward, there is a definite need to integrate mental health services into routine HIV care to include the development of cost-effective assessment and treatment strategies that have high probability of success in challenging intervention settings.

Abbreviations

- ADD:

-

Attention Deficit Disorder

- ADHD:

-

Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- APA:

-

American Psychiatric Association

- ART:

-

Anti-Retroviral Therapy

- CA-HIV:

-

Children and Adolescents infected with HIV/AIDS

- CASI-4R:

-

Child Adolescent Symptom inventory-4Revised

- CBCL:

-

Child Behavioural Checklist

- CD:

-

Conduct Disorder

- CDC:

-

Centre for Disease Control and prevention

- CDI:

-

Children’s Depression Inventory

- CI-4R:

-

Child Inventory-4Revised

- CPRS:

-

Conners’ Parent Rating Scale

- CTX:

-

Cotrimoxazole

- DISC-IV:

-

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- IMPAACT/1055:

-

International Maternal Paediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group 1055 study

- KABC:

-

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children

- KABC-II:

-

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, second edition

- ODD:

-

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- PD:

-

Psychiatric Disorder

- YI-4R:

-

Youth Inventory-4Revised

References

UNAIDS. Global Fact Sheet. 2013.

Mellins CA, Malee KM. Understanding the mental health of youth living with perinatal HIV infection: lessons learned and current challenges. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18593.

Uganda AIDS Commission. The Uganda National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 2015/2016–2019/2020. Kampala: Uganda AIDS Commission; 2015.

World Health Organisation. Treat all people living with HIV, offer antiretrovirals as additional prevention choice for people at “substantial” risk. 2015.

Abas M, Ali GC, Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Chibanda D, et al. Depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: time to act. Tropical Med Int Health. 2014;19(12):1392–6.

Ministry of Health/Uganda AIDS Commission. Uganda HIV and AIDS Country Progress report Kampala: Ministry of Health/Uganda AIDS Commission, 2014.

Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–96.

Shapshak P, Kangueane P, Fujimura RK, Levine AJ, editors. Editorial NeuroAIDS review 2011.

Van Rie A, Harrington PR, Dow A, Robertson K. Neurologic and neurodevelopmental manifestations of pediatric HIV/AIDS: a global perspective. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11(1):1–9.

Wood SM, Shah SS, Steenhoff AP, Rutstein RM. The impact of AIDS diagnoses on long-term neurocognitive and psychiatric outcomes of surviving adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS (London, England). 2009;23(14):1859–65.

Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Leu CS, Elkington KS, Dolezal C, Wiznia A, et al. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1131–8.

Mendoza R, Hernandez-Reif M, Castillo R, Burgos N, Zhang G, Shor-Posner G. Behavioural symptoms of children with HIV infection living in the Dominican Republic. West Indian Med. J. 2007;56(1):55–9.

Musisi S, Kinyanda E. Emotional and behavioural disorders in HIV seropositive adolescents in urban Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2009;86(1):16–24.

Rao R, Sagar R, Kabra SK, Lodha R. Psychiatric morbidity in HIV-infected children. AIDS Care. 2007;19(6):828–33.

Zeegers I, Rabie H, Swanevelder S, Edson C, Cotton M, van Toorn R. Attention deficit hyperactivity and oppositional defiance disorder in HIV-infected south African children. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56(2):97–102.

Kinyanda E, Hoskins S, Nakku J, Nawaz S, Patel V. Prevalence and risk factors of major depressive disorder in HIV/AIDS as seen in semi-urban Entebbe district, Uganda. BMC psychiatry. 2011;11:205.

Gadow KD, Chernoff M, Williams PL, Brouwers P, Morse E, Heston J, et al. Co-occuring psychiatric symptoms in children perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparison sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(2):116–28.

Kamau JW, Kuria W, Mathai M, Atwoli L, Kangethe R. Psychiatric morbidity among HIV-infected children and adolescents in a resource-poor Kenyan urban community. AIDS Care. 2012;24(7):836–42.

Franke B, Neale BM, Faraone SV. Genome-wide association studies in ADHD. Hum Genet. 2009;126(1):13–50.

Barkley RA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2006.

Cherkasova M, Sulla EM, Dalena KL, Ponde MP, Hechtman L. Developmental course of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and its predictors. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de l'Academie canadienne de psychiatrie de l'enfant et de l'adolescent. 2013;22(1):47–54.

Nozyce ML, Lee SS, Wiznia A, Nachman S, Mofenson LM, Smith ME, et al. A behavioral and cognitive profile of clinically stable HIV-infected children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):763–70.

Vreeman RC, Scanlon ML, McHenry MS, Nyandiko WM. The physical and psychological effects of HIV infection and its treatment on perinatally HIV-infected children. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(Suppl 6):20258.

Young S, Fitzgerald M, Postma M. ‘ADHD: making the invisible visible’, European Brain Council (EBC) & Global Alliance of Mental Illness Advocacy Networks. 2013.

Kinyanda E, Waswa L, Baisley K, Maher D. Prevalence of severe mental distress and its correlates in a population-based study in rural south-west Uganda. BMC psychiatry. 2011;8(11):97.

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Ramin M, Pierre AK, Elly K, Seggane M, Jean NB, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the self-reporting questionnaire among HIV+ individuals in a rural ART program in southern Uganda. HIV/AIDS-Research and Palliative Care. 2012;4:51–60.

WHO SRQ 20; WHO. A user’s guide of the Self Report Questionnaire (SRQ). 1994.

Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res. Nurs. Health. 2001;24(6):518–29.

Mavie C. ‘Measurement of Stigma and Relationships between Stigma,Depression, and Attachment Style among People with HIV and People with Hepatitis C’: University of Ottawa 2014.

Margolis PJ, Weintraub S. The revised 56-item CRPBI as a research instrument: reliability and factor structure. J Clin Psychol. 1977;33:472–6.

Bernstein F. Childhood trauma questionnaire: a retrospective self-report manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1998.

Kinyanda E, Hjelmeland H, Musisi S. Negative life events associated with deliberate self-harm in an African population in Uganda. Crisis. 2005;26(1):4–11.

WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595629_eng.pdf.

Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child & Adolescent Symptom Inventory-5 (Ages 5 to 18 Years) Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus.; 2013 a,b. http://www.checkmateplus.com/product/casi5.htm].

Nachman S, Chernoff M, Williams P, Hodge J, Heston J, Gadow KD. Human immunodeficiency virus disease severity, psychiatric symptoms, and functional outcomes in perinatally infected youth. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012;166(6):528–35.

Gadow KD, Angelidou K, Chernoff M, Williams PL, Heston J, Hodge J, et al. Longitudinal study of emerging mental health concerns in youth perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparisons. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2012;33(6):456–68.

Mpango RS, Kinyanda E, Rukundo GZ, Gadow K. Cross-cultural adaptation of the child and adolescent symptom Inventory-5 (CASI-5) for use in central and south-western Uganda: the CHAKA project. Submitted to Tropical Doctor 2017.

CG V, SR H, SC F, MTA O. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis; a Heirarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(1):224–7.

Vittinghoff E, Glidden D, Shibowski S, McCullough C. Regression Methods in Biostatistics, Second Edition. Chapter 10: Selection of Predictors: Springer-Verlag.; 2012.

Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child symptom Inventory-4 screening and norms manual. Checkmate Plus: Stony Brook; 2002.

Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Adolescent symptom Inventory-4 screening and norms manual. Checkmate Plus: Stony Brook; 2008.

Bakare MO. Attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and disorder (ADHD) among African children: a review of epidemiology and co-morbidities. Afr. J. Psychiatry. 2012;15(5):358–61.

Malee KM, Tassiopoulos K, Huo Y, Siberry G, Williams PL, Hazra R, et al. Mental health functioning among children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection and perinatal HIV exposure. AIDS Care. 2011b;23(12):1533–44.

Thapar A, Cooper M, Jefferies R, Stergiakouli E. What causes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder? Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(3):260–5.

Fielden SJ, Sheckter L, Chapman GE, Alimenti A, Forbes JC, Sheps S, et al. Growing up: perspectives of children, families and service providers regarding the needs of older children with perinatally-acquired HIV. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):1050–3.

Petersen I, Bhana A, Myeza N, Alicea S, John S, Holst H, et al. Psychosocial challenges and protective influences for socio-emotional coping of HIV+ adolescents in South Africa: a qualitative investigation. AIDS Care. 2010;22(8):970–8.

Mann JR, McDermott S. Are maternal genitourinary infection and pre-eclampsia associated with ADHD in school-aged children? J Atten Disord. 2011;15(8):667–73.

Millichap JG. Etiologic classification of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):e358–65.

Barkley RA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a handbook for diagnosis and treatment. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2006.

Kacanek D, Angelidou K, Williams PL, Chernoff M, Gadow KD, Nachman S, International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) P1055 Study Team. Psychiatric symptoms and antiretroviral nonadherence in US youth with perinatal HIV: a longitudinal study. AIDS (London, England). 2015;29(10):1227–37.

Gadow KD, Drabick DAG, Loney J, Sprafkin J, Salisbury H, Azizian A, et al. Comparison of ADHD symptom subtypes as source-specific syndromes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:1135–49.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the managers of the five study sites (Lubowa Joint Clinical Research Centre, Nsambya homecare department Children’s HIV Care clinic; Nsambya hospital, the Children’s clinic at The AIDS Support Organisation; TASO Masaka, Uganda Cares/Masaka Regional Referral Hospital and Kitovu Mobile AIDS Organisation, Masaka) for permitting the study to be conducted at their specialised HIV/AIDS clinics. The authors extend appreciation to the Medical Research Council, Uganda (MRC, Uganda) for funding and facilitating the study. Special gratitude is extended to the staff working at the five specialised HIV/AIDS clinics where the study was conducted. Appreciation is extended to the diligent work of research assistants. Appreciation is extended to the participants for their time and trust.

Funding

This study was funded by an MRC/DfID grant awarded to Professor Eugene Kinyanda after winning an African Leadership Award; MRC African Research Leaders MR/L004623/1 - Mental health among HIV infected CHildren and Adolescents in KAmpala, Uganda (CHAKA).

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials in this manuscript, additional files and figures attached are freely available with no restrictions.

Declarations

This the article is published as part of a supplement to the study that was funded by an MRC/DfID grant awarded to Professor Eugene Kinyanda after winning an African Leadership Award; MRC African Research Leaders MR/L004623/1 - Mental health among HIV infected CHildren / Adolescents in Kampala and Masaka, Uganda (CHAKA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RM, EK, GZR, KDG and VP have made substantial contributions to conception, design, acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, revising it critically and gave the final approval of this version to be published. JL did the analysis and interpretation of data. Each author participated sufficiently in this work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in Uganda under the authorization HS 1601 approved by the Science and Ethical Committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology. Consent to participate in this study was obtained from caregivers and assent from children and adolescents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. Gadow is shareholder in Checkmate Plus, publisher of the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-5. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Data collection tools for the study. (DOCX 30 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Characteristics of study participants. (DOC 47 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Clinical correlates of ADHD. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mpango, R.S., Kinyanda, E., Rukundo, G.Z. et al. Prevalence and correlates for ADHD and relation with social and academic functioning among children and adolescents with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. BMC Psychiatry 17, 336 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1488-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1488-7