Abstract

Background

Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common childhood neurobehavioral conditions. Symptoms related to this disorder cause a significant impairment in school tasks and in the activities of children’s daily lives; an early diagnosis and appropriate treatment could almost certainly help improve their outcomes.

The current study, part of the Models Of Child Health Appraised (MOCHA) project, aims to explore the age at which children experience the onset or diagnosis of ADHD in European countries.

Methods

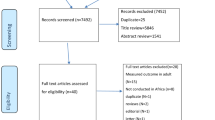

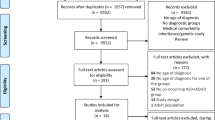

A systematic review was done examining the studies reporting the age of onset/diagnosis (AO/AD) of ADHD in European countries (28 European Member States plus 2 European Economic Area countries), published between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2019. Of the 2276 identified studies, 44 met all the predefined criteria and were included in the review.

Results

The lowest mean AO in the children diagnosed with ADHD alone was 2.25 years and the highest was 7.5 years. It was 15.3 years in the children with ADHD and disruptive behaviour disorder. The mean AD ranges between 6.2 and 18.1 years.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that there is a wide variability in both the AO and AD of ADHD, and a too large distance between AO and AD. Since studies in the literature suggest that an early identification of ADHD symptoms may facilitate early referral and treatment, it would be important to understand the underlying reasons behind the wide variability found.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registration: CRD42017070631.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which is one of the most common childhood neurobehavioral conditions, has been characterized by continually increasing global prevalence rates over the past few decades [1]. A global consensus on the ADHD prevalence rate in children and adolescents has yet to be reached: meta-regression analyses have estimated the worldwide rate at between 5.29% [2] and 7.1% [3], but according to one comprehensive meta-analysis, the best-estimate prevalence rate of study based on case definition was 1.4%, (range: 1.1–3.1) [4].

These conflicting figures have triggered the hypothesis that ADHD is either over diagnosed [5, 6], underdiagnosed, missed, or undertreated [7].

Children with unmanaged ADHD often experience unnecessary impairments and detrimental long-term consequences leading to high personal and societal costs [8, 9]. Early identification and effective management could significantly improve the functioning and overall quality of life of these children and their families.

Healthcare professionals specialized in child psychology, including the American Academy of Paediatrics, advise screening for the disorder early as the preschool period [10] so that those affected can be treated precociously permitting them to achieve their full potential in school and at home [11].

Multiple factors may affect the perception of the disorder by family members and healthcare providers and thus the timing of its diagnosis and treatment [7]. Moreover, there are numerous factors intrinsic to childhood or adolescence that could affect the diagnosis of ADHD including gender, age, race, socioeconomic status, and severity of symptoms [12, 13].

Parents play a central role in recognizing behavioural problems early in their children, their perception, awareness and acceptance of the disease, as their decision to accompany the child to a specialist [14]. Once parents decide to seek help, they need to be able to access specialised care for a timely and accurate diagnosis as well as optimal disease management strategies. Although there is an operationalized psychodynamic diagnostic process, no objective test is at yet available and substantial controversy exists regarding the challenge of formulating a correct diagnosis [15, 16]. In fact, conflicting views continue to exist with regard to the symptoms and psychometric features leading to a diagnosis of ADHD diagnosis [17,18,19].

Many clinicians depend on and utilize the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) [20] for guidance in making diagnoses, even if general diagnostic issues (e.g. model of diagnosis and level of impairment) need of better clarification [17] also using different diagnostic criteria, such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and the Research Domain Criteria.

Although the heterogeneity in the methodology of diagnosing of ADHD has resulted in a high variability in prevalence rates around the world [21], differences linked to age at diagnosis (AD) or onset (AO) of ADHD need to be investigated.

Within the Models Of Child Health Appraised (MOCHA) project [22], which has been critically assessing the existing models of primary care for children in 30 European countries (28 European Member States plus 2 European Economic Area countries), Minicuci et al. [23] have been involved in investigating the AO and AD of ADHD.

The current work set out to examine the studies involving children with ADHD in European countries that report their age at onset or diagnosis.

Methods

Following a systematic review approach and a standardized method of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [24], we searched for studies that reported the AO or AD of ADHD. The review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42017070631). The PRISMA checklist for this systematic review is presented in Additional file 1.

We searched the Medline (PubMed) database for studies in the literature examining ADHD onset or diagnosis published between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2019. It was decided to limit the review to the last decade because it is the one in which the clinical guideline’s recommendations previously produced by many parties had to be consolidated also with the fifth revision of the DSM started in 2000 and finished in 2013 [25]. The search terms used were: “ADHD”, “Attention deficit”, “Hyperactivity Disorder” and “Attention disorder” in the title or abstract, combined with “age”, “onset” or “diagnosis” and “child” or “adolescent” in the text word (see Additional file 1 for details). Any study not in English were excluded. In order to include all studies reporting ADHD AO/AD, no exclusion criteria was applied to diagnostic criteria/tools used for participants’ diagnosis in the studies reviewed. The diagnostic criteria or tools adopted in each included study, as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria followed to select the study sample, have been examined at a later time with other relevant characteristics.

The abstracts of all the articles were read and the full version of the papers for those seemingly fulfilling the selection criteria were retrieved.

Studies were included in this review if they reported the AO or AD for ADHD and were conducted in or referred to data from a European country.

We utilized a standardized form for data extraction that included the following items: the authors’ names, the year of publication, the country in which the study was performed, the journal in which the study was published, the type of study, the aim of the study, the year in which the study was performed, the types of persons composing the study sample (including age and sample size), the diagnostic criteria adopted for the diagnosis, and, of course, the AO/ADs.

Two of the authors (IR and BC) screened all the articles; any differences in viewpoints that arose were resolved through discussion with the third author (NM).

Results

The initial PubMed search yielded 2276 studies (Fig. 1). After the abstracts were screened, a total of 1163 articles were excluded, mainly because the population studied and/or the geographic area (did not meet our criteria, in the former case for age, in the latter it referred to studies outside Europe). Out of the 1113 full-text articles reviewed, 49.1% were carried out outside Europe and 43.4% did not report AO or AD. Forty-four articles met our inclusion criteria for this review.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the studies included are outlined in Table 1. Twenty-three articles were published in 2010–15 and 21 articles in 2016–19.

One article reported both the AD and the AO, 34 studies reported only the AD, and 9 reported only the AO. The majority of the studies included in this review were conducted in Sweden (7 articles) and in Germany (5 articles), followed by 3 countries publishing 4 articles each.

Table 2 provides a full list of the 44 studies mentioned here, in the order of their publication date; its chronological number is also used throughout the text in all subsequent references to that article.

Diagnostic criteria

In the majority of the articles, the diagnostic criteria used to define ADHD symptoms or to formulate a diagnosis of ADHD was the DSM. One study conducted in Sweden [31] reported that the DSM criteria in the DSM-III-R [70] and in the DSM-IV [71] were used before and after 1994 respectively; while in the study of van Lieshout et al. [53] the DSM-IV and DSM-5 [72] were adopted. In eight papers the 4th edition (DSM-IV) was adopted, in five papers the “text revision” of the DSM-IV, namely the DSM-IV-TR [73], was used. The DSM-IV items of the Conners’ teacher questionnaire were used with the Parental Account of Childhood Symptoms (PACS) interview in the study by Muller and colleagues [32].

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 3.0 was used to determine the presence of ADHD according to the DSM-IV criteria in the article by Tuithof and collaborators [36]. Developed by the World Health Organization, the CIDI is a fully structured, lay administered interview used worldwide that has been shown to be a reliable and valid instrument [74].

We also identified 15 papers using the ICD to define ADHD symptoms or to make an ADHD diagnosis. Among these papers, one article [47] used both the 9th [75] and 10th [76] editions; the remaining articles used the 10th edition.

In three articles, multiple sources of information were taken into consideration for the diagnosis of ADHD. The diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV and the ICD-9/ICD-10 were adopted and the results of Conner’s questionnaire were considered in the six countries involved in the study by Hodgkins and collaborators [39]. In the article by Chen and collaborators [57], the individuals who were diagnosed with hyperkinetic disorder (ICD-9, ICD-10) or ADHD (DSM-IV) were defined as ADHD cases; in Bahmanyar et al. [38] the ICD-10 and DSM-IV were adopted.

The semistructured Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) is a DSM-IV-based diagnostic interview procedure that was used in some of the articles to support ADHD diagnosis [41, 53, 59].

Two studies [65, 66] used Read codes for an ADHD diagnosis. Read codes are clinical terminology developed in the UK by the National Health Service (NHS) based on clinical parameters and usage.

Read codes have become the de facto standard for coding diagnoses, operations, and procedure for all national data sets and statistics on hospital and community health services in the UK.

Lastly, the diagnostic criteria utilized were not specified in six articles. In three papers [43, 45, 58], parents/caregivers of children and adolescents were asked if their children had ever been diagnosed with ADHD by a doctor or other healthcare professional; in a paper by Caci and colleagues [49] the physicians treating children with ADHD were asked to select patients to enrol in the study; finally, the patients were identified from the psychiatric cases and drug registers in two articles [48, 64].

Age at onset

Eight out of 10 of the studies presenting information on the AO reported the mean, median or age range at symptom onset in the sample of children being studied [26, 29, 35, 36, 41, 49, 51, 53]. The lowest AO was reported by a Dutch study examining a sample made up of 347 patients with combined ADHD, whose ages were between 5 and 19 years; the first ADHD symptom appeared at a mean age of 2.25 years [53]. The highest AO was reported in a study referring to children in Finland: it was 7.5 years in the children with only ADHD diagnosis and 15.3 years in the children with comorbid ADHD and disruptive behaviour disorder (DBD) [41].

The study by Muller and colleagues [32] reported the time of ADHD detection rather than the time of symptom onset which was analysed by comparing probands with combined ADHD with their siblings without ADHD diagnosis or to different subtypes of ADHD.

Polanczyk et al. [28] focused on the implications of extending the ADHD AO criterion from ages 7 to 12 years, since the variation would lead to a negligible increase in ADHD prevalence (0.1% in their cohort) by age 12.

Age at diagnosis

Thirty-two of the 35 studies presenting information on the AD of ADHD reported its mean, median, range or distribution, one study presented the peak of the ADHD incidence in males and females [63]; in two other studies, information on the AD was inferred through the graphical representations of the cumulative incidence of ADHD diagnosis among siblings and cousins [57] and of the prevalence of ADHD diagnosis in an insured population [55].

The age range in the 24 studies reporting the mean AD was 6.2 to 18.1 years. The lowest mean value, which was reported by Andreou and Trott [37], concerned a group of 30 university students living in Greece who were diagnosed with ADHD during childhood (26 a combined form and 4 a hyperactive impulsive form).

Granström et al. [64] reported the highest mean AD in 26 individuals with Hirschsprung disease and 7390 controls taking any drug for the treatment of ADHD according to the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register.

Two studies reported the mean age for ADHD diagnosis for a specific group of countries [39, 43]. Taking into consideration the same countries (i.e. France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and UK), the two studies identified Germany as the country with the lowest mean age and the UK [39] and the Netherlands [43] as the countries with the highest mean age.

Discussion

ADHD, one of the most common childhood neurodevelopmental disorders, is characterized by a pattern of inattention and/or impulsivity and hyperactivity, behaviours that can have a dramatic impact on children and on family life [77]. Since early identification of the disease is essential to optimize the quality of life of both the children themselves and their families, there is growing research interest in investigating the timing of diagnosis which can lead to prompt medical attention.

The current study set out to investigate age at the time of onset and/or diagnosis of ADHD in children living in European countries by examining the studies published between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2019 reporting on the AO and AD of ADHD. The study’s most important finding was that there is a wide variability in both.

Much of the variability could be attributed to discrepancies in study methods. Differences in study designs, ranging from case-control, cohort, to cross-sectional, could have affected the AO/AD as a cohort study could more accurately identify the AO and thus the incidence of ADHD with respect to a cross-sectional retroactive study basing its figures on parent reports.

The studies also show differences in sampling methods. Several studies, in fact, used convenience samples from clinic-based studies; others were based on registry data or medical records. It is reasonable to hypothesise that referred patient samples have lower AO/AD compared to community cohorts given the differences in the severity of the disorder in these populations.

The source of information (self-reported, parent-reported, teacher-reported, doctor-reported) can also significantly influence the figures on the AO/AD registered by the different studies. In a multi-country cross-section study by Caci et al. [43] which assessed the degree to which ADHD impairs patients’ everyday lives, the diagnosis was caregiver-reported and the mean AD was 7.0 years, ranging from 6.3 years in Germany to 7.6 years in the Netherlands. The diagnosis was obtained following the consultation of a mean of 2.7 doctors, ranging from 2.3 in the Netherlands to 3.2 in France, over a mean period of 20.4 months, ranging from 12.2 in Spain to 31.8 in the UK.

The articles by Genuneit et al. [45] and Pohlabeln et al. [58] presented the parent-reported AD: in the first, 44% of the children included in the sample were diagnosed before the age of 8 years and the others between 9 and 11 years; in the second article the percentage of children diagnosed between 9 and 11 years fell to 17%. Although the age range as well as the source of information (parent-reported) of these two articles was the same, the differences in AD could probably be explained by the presence of a comorbidity, that is Atopic Eczema in the case of the first sample.

The presence of comorbidities is an exceedingly important consideration when ADHD diagnosis is being discussed. ADHD symptoms can overlap with those of other disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, disorders of mood and conduct, oppositional defiant disorder, learning difficulties, impaired motor control, poor executive functions (working memory, planning, organisation, and time management), communication difficulties, sleep disorders, tics/Tourette syndrome, epilepsy, and anxiety disorders, that commonly coexist with ADHD.

Socanski et al. [42], who compared the ADs of ADHD in a group of children with epilepsy and a control group, uncovered a statistically significant different in the mean ages: the children with epilepsy had a mean AD of 8.2 years, while those without epilepsy had a mean AD of 9.4 years (p-value = 0.07). This result suggests that children with comorbidities related to ADHD have a greater probability of being diagnosed with ADHD at a younger age, presumably because they already have access to some kind of healthcare services and are being monitored by medical specialists.

Thus, the characteristics of enrolled populations (exclusion/inclusion criteria) and the sample size enormously undermine the evaluation and comparison of studies as well as a formal summary of the results. The application of meta-analysis is also impossible due to the lack of publication by all the studies of the absolute values.

The criteria used to diagnose the condition is another important factor that could affect the heterogeneity in the studies considered.

The two main diagnostic systems currently being used are the ICD-10 and the DSM-V [72]. Both systems require that symptoms be present in several settings, for example school/work, home life and leisure activities, and that the onset of symptoms be evident in early life, although this criterion has not yet received a consensus among specialists and has changed over the last decades. For the DSM-V, onset is expected to occur by the age of 12 years; for the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV by the age of 7 years. Since AO itself is one of the criteria of a diagnosis of ADHD in the studies included in our analysis, the AD falls within the ages determined by the diagnostic criteria.

Several research teams have been concerned about the implications of increasing the age of onset to 12 years [78]. Some investigators seem favourable to adopting the new criteria since it has increased the number of ADHD patients receiving help [79]. Other researchers believe that parents’ inability to recall the AO prior to 7 years might give false negative results and reduce some of the diagnostic relevance connected to recalling the AO [80]. A revision of AO criteria should in any case be based on studies assessing the performance of different diagnostic criteria in the population [79].

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this study represents the first systematic review of the AO and AD of ADHD in European countries. Although we did adhere to PRISMA guidelines [24] to ensure methodological rigour, the study does have a number of potential limitations.

The first is that studies not published in English as well as those not available in PubMed were not taken into consideration.

We would also like to point out that the 44 articles included in this systematic review refer to studies conducted in 13 European countries.

Despite these limitations, and those methodological of analysed studies, the review offers new insights into the timing of the onset and diagnosis of ADHD.

Conclusions

One of the key functions of primary care is to recognize the symptoms of an illness at an early stage. As far as childhood illnesses are concerned, neurodevelopmental disorders are relatively common and increasing in Europe. Early diagnosis makes it possible to contemplate and implement opportune treatment strategies thus reducing, in this case, some of ADHD’s adverse current and future consequences in the child and family. This study provides a preliminary overview on the timing of the onset and the diagnosis of ADHD in children living in European countries. The long term validity and heterogeneity of the classification systems used to guide diagnoses and the factors behind the social, cultural and genetic differences affecting the timing of identification of the syndrome need further analysis. The fact that Germany has a much earlier AO and AD with respect to the UK and the Netherlands is just one example of differences that need to be clarified. Studies in the literature suggest that identifying ADHD symptoms early on can facilitate early referral and treatment, and thus limit its cost in personal and societal terms [81, 82]. To optimize the quality of the service and of the care delivered is the task of both policymakers and clinical experts. To guarantee an equal standard of care for all children and adolescents with ADHD is a pressing need to reduce the times to complete the diagnostic path, and promptly star with appropriate therapy [83]. However, further studies are necessary to uncover the underlying reasons for the large variability observed in both AO and AD, and reducing the distance between the onset and the diagnosis of ADHD.

Availability of data and materials

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Change history

21 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03703-x

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

- AD:

-

Age of diagnosis

- AO:

-

Age of onset

- ADHD-RS:

-

ADHD Rating Scale-IV

- ADI-R:

-

Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised

- ADOS-G:

-

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Generic

- ASSQ:

-

Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire

- BD:

-

Bipolar Disorder

- DSRS:

-

Birleson Depression Self-Rating Scale

- CAPA:

-

Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment

- CBCL:

-

Child Behavior Checklist for parents

- CDI:

-

Children’s Depression Inventory

- CMAS:

-

Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale

- CGI-S:

-

Clinical global impressions–severity scale

- CIDI:

-

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

- CAARS-S:L:

-

Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales-Self-Report: Long Version

- CPRS:

-

Conners’ Parent Rating Scale

- CPRS-R:L:

-

Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long version

- CTRS-R:L:

-

Conners’ Teachers’ Rating Scale–Revised: Long Form

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- DBD:

-

Disruptive Behaviour Disorder

- DBRS:

-

Disruptive Behaviour Rating Scale

- FTF:

-

Five to Fifteen questionnaire

- GAF:

-

Global Assessment of Functioning Scale

- H/I:

-

Hyperactivity/Impulsivity

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- MPH:

-

Methylphenidate

- MOCHA:

-

Models Of Child Health Appraised

- PACS:

-

Parental account of childhood symptoms

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- K-SADS-PL:

-

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version

- SDQ:

-

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SWAN:

-

Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behaviour

- VABS-DLS:

-

Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales–Daily Living Skills domain

- WAIS-R:

-

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised

- WISC-III:

-

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition

- WPPSIR:

-

Wechsler Preschool & Primary Scale of Intelligence–Revised

- WURS:

-

Wender Utah Rating Scale

References

Boyle CA, Boulet S, Schieve LA, Cohen RA, Blumberg SJ, Yeargin-Allsopp M, et al. Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997–2008. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1034–42.

Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942.

Willcutt EG. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(3):490–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-012-0135-8.

Reale L, Bonati M. ADHD prevalence estimates in Italian children and adolescents: a methodological issue. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44(1):108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0545-2.

Batstra L, Nieweg EH, Pijl S, Van Tol DG, Hadders-Algra M. Childhood ADHD: a stepped diagnosis approach. J Psychiatr Pract. 2014;20(3):169–77. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000450316.68494.20.

Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, Ghandour RM, et al. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003-2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(34–46):e32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001.

Hamed AM, Kauer AJ, Stevens HE. Why the diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity disorder matters. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00168.

Caci H, Asherson P, Donfrancesco R, Faraone SV, Hervas A, Fitzgerald M, et al. Daily life impairments associated with childhood/adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as recalled by adults: results from the European lifetime impairment survey. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(2):112–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852914000078.

Biederman J, Monuteaux M, Mick E, et al. Young adult outcome of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a controlled 10 year follow-up study. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):167–79. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291705006410.

Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity D, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management, Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, Du Paul G, et al. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007–22. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2654.

Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, Biederman J. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: is it an American condition? World Psychiatry. 2003;2(2):104–13.

Bussing R, Gary FA, Mills TL, Garvan CW. Parental explanatory models of ADHD: gender and cultural variations. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(10):563–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-003-0674-8.

Able SL, Johnston JA, Adler LA, Swindle RW. Functional and psychosocial impairment in adults with undiagnosed ADHD. Psychol Med. 2007;37(1):97–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706008713.

Zwaanswijk M, Verhaak PF, Bensing JM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Help seeking for emotional and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: a review of recent literature. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;12(4):153–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-003-0322-6.

Ford-Jones P. Misdiagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: ‘Normal behaviour’ and relative maturity. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20(4):200–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/20.4.200.

Taylor E. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: overdiagnosed or diagnoses missed? Arch Dis Child. 2016;102(4):376–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-310487.

Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow E. Conners’ adult ADHD rating scales technical manual. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems; 1999.

World Health Organization. Hyperkinetic disorder. In: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and related health problems. 10th ed; 1992.

Smyth AC, Meier ST. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Conners adult ADHD rating scales. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(10):1111–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715624230.

Bell AS. A critical review of ADHD diagnostic criteria: what to address in the DSM-V. J Atten Disord. 2011;15(1):3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054710365982.

Levy F, Hay DA, Bennett KS, McStephen M. Gender differences in ADHD subtype comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(4):368–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000153232.64968.c1.

MOCHA Project www.childhealthservicemodels.eu, access date: 27 November 2018.

Minicuci N, Corso B, Rocco I. (2016) Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Literature – Part 2. Retrieved from: http://www.childhealthservicemodels.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/D1.1-part-2-Systematic-review.pdf

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and Meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Wolraich ML, Hagan JF, Allan C, et al. Subcommittee on Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactive Disorder. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20192528. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2528.

Bernardi S, Cortese S, Solanto M, Hollander E, Pallanti S. Bipolar disorder and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. A distinct clinical phenotype? Clinical characteristics and temperamental traits. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(4):656–66. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622971003653238.

Kopp S, Kelly KB, Gillberg C. Girls with social and/or attention deficits: a descriptive study of 100 clinic attendees. J Atten Disord. 2010;14(2):157–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054709332458.

Polanczyk G, Caspi A, Houts R, Kollins SH, Rohde LA, Moffitt TE. Implications of extending the ADHD age-of-onset criterion to age 12: results from a prospectively studied birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(3):210–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2009.12.014.

Prihodova I, Paclt I, Kemlink D, Skibova J, Ptacek R, Nevsimalova S. Sleep disorders and daytime sleepiness in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a two-night polysomnographic study with a multiple sleep latency test. Sleep Med. 2010;11(9):922–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.03.017.

Berek M, Kordon A, Hargarter L, Mattejat F, Slawik L, Rettig K, et al. Improved functionality, health related quality of life and decreased burden of disease in patients with ADHD treated with OROS® MPH: is treatment response different between children and adolescents? Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-5-26.

Gustafsson P, Källén K. Perinatal, maternal, and fetal characteristics of children diagnosed with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder: results from a population-based study utilizing the Swedish Medical Birth Register. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(3):263–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03820.x Erratum in: Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011 May;53(5):478.

Müller UC, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar JK, Ebstein RP, Eisenberg J, et al. The impact of study design and diagnostic approach in a large multi-Centre ADHD study. Part 1: ADHD symptom patterns. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-54.

Durá-Travé T, Yoldi-Petri ME, Gallinas-Victoriano F, Zardoya-Santos P. Effects of osmotic-release methylphenidate on height and weight in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) following up to four years of treatment. J Child Neurol. 2012;27(5):604–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073811422752.

Garbe E, Mikolajczyk RT, Banaschewski T, Petermann U, Petermann F, Kraut AA, et al. Drug treatment patterns of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents in Germany: results from a large population-based cohort study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):452–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2012.0022.

Kirov R, Uebel H, Albrecht B, Banaschewski T, Yordanova J, Rothenberger A. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and adaptation night as determinants of sleep patterns in children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(12):681–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0308-3.

Tuithof M, ten Have M, van den Brink W, Vollebergh WAM, de Graaf R. The role of conduct disorder in the association between ADHD and alcohol use (disorder). Results from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence Study-2. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123(2012):115–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.030.

Andreou G, Trott K. Verbal fluency in adults diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in childhood. ADHD Atten Deficit Hyperactivity Disord. 2013;5(4):343–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-013-0112-z.

Bahmanyar S, Sundström A, Kaijser M, von Knorring AL, Kieler H. Pharmacological treatment and demographic characteristics of pediatric patients with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity disorder, Sweden. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(12):1732–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.07.009.

Hodgkins P, Setyawan J, Mitra D, Davis K, Quintero J, Fridman M, et al. Management of ADHD in children across Europe: patient demographics, physician characteristics and treatment patterns. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(7):895–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-013-1969-8 Epub 2013 Feb 26.

McCarthy H, Skokauskas N, Mulligan A, Donohoe G, Mullins D, Kelly J, et al. Attention network hypoconnectivity with default and affective network hyperconnectivity in adults diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1329–37. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2174.

Nordström T, Hurtig T, Moilanen I, Taanila A, Ebeling H. Disruptive behaviour disorder with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a risk of psychiatric hospitalization. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(11):1100–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12383 Epub 2013 Aug 30.

Socanski D, Aurlien D, Herigstad A, Thomsen PH, Larsen TK. Epilepsy in a large cohort of children diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders (ADHD). Seizure. 2013;22(8):651–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2013.04.021 Epub 2013 May 24.

Caci H, Doepfner M, Asherson P, Donfrancesco R, Faraone SV, Hervas A, et al. Daily life impairments associated with self-reported childhood/adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and experiences of diagnosis and treatment: results from the European lifetime impairment survey. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(5):316–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.10.007 Epub 2013 Dec 16.

Dalsgaard S, Leckman JF, Nielsen HS, Simonsen M. Gender and injuries predict stimulant medication use. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(5):253–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2013.0101 Epub 2014 May 9.

Genuneit J, Braig S, Brandt S, Wabitsch M, Florath I, Brenner H, et al. Infant atopic eczema and subsequent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder--a prospective birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25(1):51–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.12152 Epub 2013 Dec 1.

Steinhausen HC, Bisgaard C. Substance use disorders in association with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, co-morbid mental disorders, and medication in a nationwide sample. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(2):232–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.11.003 Epub 2013 Nov 18.

Sucksdorff M, Lehtonen L, Chudal R, Suominen A, Joelsson P, Gissler M, et al. Preterm birth and poor fetal growth as risk factors of Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2015;136(3):e599–608. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1043.

van den Ban EF, Souverein PC, van Engeland H, Swaab H, Egberts TC, Heerdink ER. Differences in ADHD medication usage patterns in children and adolescents from different cultural backgrounds in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(7):1153–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1068-4 Epub 2015 May 28.

Caci H, Cohen D, Bonnot O, Kabuth B, Raynaud JP, Paillé S, et al. Health Care Trajectories for Children With ADHD in France: Results From the QUEST Survey. J Atten Disord. 2016; Epub ahead of print.

Lemcke S, Parner ET, Bjerrum M, Thomsen PH, Lauritsen MB. Early development in children that are later diagnosed with disorders of attention and activity: a longitudinal study in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016; Epub ahead of print.

Rheims S, Herbillon V, Villeneuve N, Auvin S, Napuri S, Cances C, et al. ADHD in childhood epilepsy: clinical determinants of severity and of the response to methylphenidate. Epilepsia. 2016;57(7):1069–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13420 Epub 2016 May 29.

Sollie H, Larsson B. Parent-reported symptoms, impairment, helpfulness of treatment, and unmet service needs in a follow-up of outpatient children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;70(8):582–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2016.1187204 Epub 2016 Jun 7.

van Lieshout M, Luman M, Twisk JW, van Ewijk H, Groenman AP, Thissen AJ, et al. A 6-year follow-up of a large European cohort of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-combined subtype: outcomes in late adolescence and young adulthood. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016; Epub ahead of print.

Abel MH, Ystrom E, Caspersen IH, Meltzer HM, Aase H, Torheim LE, et al. Maternal Iodine Intake and Offspring Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Results from a Large Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2017;9(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9111239.

Bachmann CJ, Philipsen A, Hoffmann F. ADHD in Germany: trends in diagnosis and pharmacotherapy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(9):141–8. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2017.0141.

Balboni G, Incognito O, Belacchi C, Bonichini S, Cubelli R. Vineland-II adaptive behavior profile of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or specific learning disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2017;61:55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2016.12.003 Epub 2017 Jan 2.

Chen Q, Brikell I, Lichtenstein P, Serlachius E, Kuja-Halkola R, Sandin S, et al. Familial aggregation of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(3):231–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12616 Epub 2016 Aug 22.

Pohlabeln H, Rach S, De Henauw S, Eiben G, Gwozdz W, Hadjigeorgiou C, et al. IDEFICS consortium. Further evidence for the role of pregnancy-induced hypertension and other early life influences in the development of ADHD: results from the IDEFICS study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(8):957–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-0966-2 Epub 2017 Mar 3.

Sayal K, Chudal R, Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S, Joelsson P, Sourander A. Relative age within the school year and diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(11):868–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30394-2 Epub 2017 Oct 9.

Bonati M, Cartabia M, Zanetti M, Reale L, Didoni A, Costantino MA, et al. Age level vs grade level for the diagnosis of ADHD and neurodevelopmental disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1180-6 Epub ahead of print.

Cornu C, Mercier C, Ginhoux T, Masson S, Mouchet J, Nony P, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomised trial of omega-3 supplementation in children with moderate ADHD symptoms. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(3):377–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1058-z Epub 2017 Oct 5.

Prasad V, West J, Sayal K, Kendrick D. Injury among children and young people with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the community: the risk of fractures, thermal injuries, and poisonings. Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44(6):871–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12591 Epub 2018 Jul 24.

Dalsgaard S, Thorsteinsson E, Trabjerg BB, Schullehner J, Plana-Ripoll O, Brikell I, et al. Incidence Rates and Cumulative Incidences of the Full Spectrum of Diagnosed Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3523 Epub ahead of print.

Granström AL, Skoglund C, Wester T. No increased risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorders in patients with Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(10):2024–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.10.067 Epub 2018 Nov 7.

Hoang U, James AC, Liyanage H, Jones S, Joy M, Blair M, et al. Determinants of inter-practice variation in ADHD diagnosis and stimulant prescribing: cross-sectional database study of a national surveillance network. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2019;24(4):155–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111133 Epub 2019 Feb 14.

Root A, Brown JP, Forbes HJ, Bhaskaran K, Hayes J, Smeeth L, et al. Association of Relative Age in the School Year With Diagnosis of Intellectual Disability, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and Depression. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3194 Epub ahead of print.

Sun S, Kuja-Halkola R, Faraone SV, D'Onofrio BM, Dalsgaard S, Chang Z, et al. Association of psychiatric comorbidity with the risk of premature death among children and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1944 Epub ahead of print.

Sourander A, Sucksdorff M, Chudal R, Surcel HM, Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S, Gyllenberg D, et al. Prenatal cotinine levels and ADHD among offspring. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3144.

Taylor MJ, Larsson H, Gillberg C, Lichtenstein P, Lundström S. Investigating the childhood symptom profile of community-based individuals diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as adults. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(3):259–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12988 Epub 2018 Oct 19.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders text revision. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349.

Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, De Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, et al. Concordance of the composite international diagnostic interview version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO world mental health surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2006;15(4):167–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.196.

World Health Organization. International classification of diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1977.

World Health Organization. International classification of diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

Coghill D, Seth S. Effective management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) through structurated re-assessment: the Dundee ADHD clinical care pathway. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0083-2.

Chandra S, Biederman J, Faraone SV. Assessing the validity of the age at onset criterion for diagnosing ADHD in DSM-5. J Atten Disord. 2016;25(2):143–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716629717.

Coghill D, Seth S. Do the diagnostic criteria for ADHD need to change? Comments on the preliminary proposals of the DSM-5 ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders Committee. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:75–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-010-0142-4.

Epstein JN, Loren RE. Changes in the definition of ADHD in DSM-5: subtle but important. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3:455–8. https://doi.org/10.2217/npy.13.59.

Foy JM, Earls MF. A process for developing community consensus regarding the diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):e97–e104. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0953.

Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Olazagasti MA, Roizen E, Hutchison JA, Lashua EC, et al. Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1295–303. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.271.

Bonati M, Cartabia M, Zanetti M, Lombardy ADHD Group. Waiting times for diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents referred to Italian ADHD centers must be reduced. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:673. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4524-0.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the MOCHA project, that was funded by the European Commission through the Horizon 2020 Framework [grant agreement number: 634201] but this work was produced subsequently without funding. The funding body was not involved in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IR and BC screened all the articles present in this review; IR wrote the manuscript; IR, BC, MB interpreted the data; all authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: the corresponding author has been correctly assigned.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rocco, I., Corso, B., Bonati, M. et al. Time of onset and/or diagnosis of ADHD in European children: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 21, 575 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03547-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03547-x