Abstract

Background

Langerhans cell histiocytosis affecting the thyroid commonly presents with nonspecific clinical and radiological manifestations. Thyroid Langerhans cell histiocytosis is typically characterized by non-enhancing hypodense lesions with an enlarged thyroid on computed tomography medical images. Thyroid involvement in LCH is uncommon and typically encountered in adults, as is salivary gland involvement. Therefore, we present a unique pediatric case featuring simultaneous salivary and thyroid involvement in LCH.

Case presentation

A 3-year-old boy with complaints of an anterior neck mass persisting for 1 to 2 months, accompanied by mild pain, dysphagia, and hoarseness. A physical examination revealed a 2.5 cm firm and tender mass in the left anterior neck. Laboratory examinations revealed normal thyroid function test levels. Ultrasonography revealed multiple heterogeneous hypoechoic nodules with unclear and irregular margins in both lobes of the thyroid. Contrast-enhanced neck computed tomography revealed an enlarged thyroid gland and bilateral submandibular glands with non-enhancing hypointense nodular lesions, and multiple confluent thin-walled small (< 1.5 cm) cysts scattered bilaterally in the lungs. Subsequently, a left thyroid excisional biopsy was performed, leading to a histopathological diagnosis of LCH. Immunohistochemical analysis of the specimen demonstrated diffuse positivity for S-100, CD1a, and Langerin and focal positivity for CD68. The patient received standard therapy with vinblastine and steroid, and showed disease regression during regular follow-up of neck ultrasonography.

Conclusions

Involvement of the thyroid and submandibular gland as initial diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis is extremely rare. It is important to investigate the involvement of affected systems. A comprehensive survey and biopsy are required to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is the monoclonal proliferation of Langerhans cells presenting with CD1a + /CD207 (Langerin) + markers in lesions [1]. The annual incidence of this disease is 8.9 per million children, under 15 years of age [2]. LCH can affect many organs, including the bones, skin, lungs, lymph nodes, hypothalamus-pituitary axis, liver, and spleen. The incidence of thyroid involvement is relatively low at 14% in children and 10.10% in adults according to a single-center analysis [3]. Hence, its rare occurrence may lead to delayed diagnosis or misdiagnoses. Herein, we reported the case of a pediatric patient who presented with an anterior neck mass as the first clinical manifestation.

Case presentation

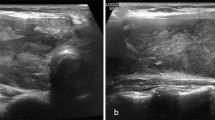

A 3-year-old boy presented to our outpatient department with complaints of an anterior neck mass persisting for 1 to 2 months, accompanied by mild pain, dysphagia, and hoarseness. He had no fever, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, palpitations, or developmental problems. A physical examination revealed a 2.5 cm firm and tender mass in the left anterior neck; the other systems appeared normal. The patient had no known systemic disease, family history of thyroid disease, or malignancies. Laboratory examinations revealed normal thyroid function with levels of thyroid stimulating hormone at 3.679 μIU/mL (normal range: 0.350–4.940 μIU/mL), free thyroxine (free T4) at 1.27 ng/dL (normal range: 0.70–1.48 ng/dL), and triiodothyronine (T3) at 1.66 ng/mL (normal range: 0.58–1.59 ng/mL). Additionally, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 58 mm/h (normal range: < 12 mm/h), lactate dehydrogenase level of 267 IU/L (normal range: 98–192 IU/L), microcytic anemia with hemoglobin of 11.6 g/dL (normal range: 13–18 g/dL), and mean corpuscular volume of 74.8 fL (normal range: 80–98 fL), and thrombocytosis with platelet count of 713 × 103/μL (normal range: 140–450 × 103/μL) were noted. In addition, white blood cell count, renal function, liver function, calcitonin, and electrolyte levels were within normal limits. Ultrasonography (US) revealed multiple heterogeneous hypoechoic nodules with unclear and irregular margins in both lobes of the thyroid (Fig. 1a). Contrast-enhanced neck computed tomography (CT) revealed an enlarged thyroid gland and bilateral submandibular glands with non-enhancing hypointense nodular lesions (Figs. 1b and 2b), and multiple confluent thin-walled small (< 1.5 cm) cysts scattered bilaterally in the lungs (Fig. 2a). Given the preliminary diagnosis of lymphoma or another infiltrative disease and following discussions with the patient's family, the excisional biopsy was more appropriate than percutaneous aspiration or core biopsy. Thereafter, left thyroid excisional biopsy was performed, leading to a histopathological diagnosis of LCH. Immunohistochemical analysis of the specimen demonstrated diffuse positivity for S-100, CD1a, and Langerin (Fig. 3) and focal positivity for CD68. The patient received standard treatment with vinblastine and steroid. Subsequent follow-up thyroid ultrasonography revealed significant resolution of the heterogeneous hypoechoic nodules (Fig. 4). The patient is currently keeping treatment and follow-up.

a Axial non-contrast enhanced computed tomography shows the typical pattern of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis with multiple small confluent thin-walled cysts. b Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography shows enlarged bilateral submandibular glands with multiple non-enhancing hypodense nodules within

Discussion and conclusions

The pituitary gland is the most common site of endocrine system involvement in LCH, typically presenting as diabetes insipidus (DI) and, occasionally, as central hypothyroidism [4]. Thyroid LCH is a rare occurrence with only a few reported cases [3], and can be indistinguishable from other thyroid disorders presenting with goiter, which may lead to a delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. To the best of our knowledge, our patient is the only case with simultaneous involvement of salivary gland and thyroid gland reported within the recent 5 years (Table 1). Patients with thyroid LCH mostly present with euthyroidism or hypothyroidism, although hyperthyroidism and subclinical hypothyroidism have been reported in few cases [5]. In fact, in our case, subacute thyroiditis with subclinical hyperthyroidism was initially diagnosed before biopsy-confirmed LCH diagnosis and was ineffectively treated with low-dose steroids.

On US, thyroid LCH can present as either diffuse or nodular hypoechoic lesion [3], our case demonstrates diffuse heterogeneous of both thyroid lobes with hypoechoic nodularities as well. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), core needle biopsy (CNB), and surgical approaches are used to establish a diagnosis. In a cohort study [3], the reported sensitivity of FNAB was 37.5%, and the overall sensitivity of CNB or thyroid surgery was 100%. Notably, thyroid LCH may be misinterpreted as papillary thyroid carcinoma or autoimmune thyroiditis [19]. Therefore, immunohistochemical staining for CD1a, S100, and Langerin (CD207) is required for establishing a definitive diagnosis [20].

LCH can manifest as either focal or disseminated disease, affecting the skeletal system, lungs, thymus, hepatobiliary system, gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, soft tissues of the head and neck, salivary glands, and rarely the thyroid. The appearance of LCH lesions is associated with the underlying histopathological phases of progression from the initial proliferative phase to the granulomatous, xanthomatous, and fibrous phases [21]. Roentgenological findings of early skeletal lesions manifest as poorly defined osteolytic (punch-out) lesions with lamellated periosteal reaction, whereas late lesions appear well defined with sclerotic margins with an expanded remodeled appearance [21]. Pulmonary LCH lesions show diffuse, bilateral, symmetric, and centrilobular reticulonodular opacities that gradually turn into confluent cysts [21]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of LCH in the central nervous system include loss of the posterior bright spot of the pituitary gland, thickening of the pituitary stalk greater than 3 mm with enhancement, and a mass lesion with iso-intensity and homogeneous enhancement under T1-weighted images [22], as well as neurodegenerative changes in the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum, cerebellar white matter, pons, or basal ganglia causing hyperintensities on T2-weighted images [23]. Thyroid involvement manifests as thyromegaly with hypodense lesions, without enhancement on CT images [24]. Salivary gland involvement, which is rare and has no pathognomonic imaging characteristics, manifests as a homogeneously enlarged gland with heterogeneous enhancement but without necrosis or calcification [25, 26]. However, our case uniquely displayed an extremely rare occurrence of involvement of both the thyroid and submandibular glands, with no evidence of central DI. To the best of our knowledge, we have not encountered a similar case in the English literature thus far.

Thyroid uptake and scintigraphy may assist in the diagnosis of cold defects [27]. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography is a useful modality for detecting systemic involvement in LCH [28]; however, it has been reported to show insignificant findings in patients with pathologically confirmed LCH [12].

Following the guideline for patients under 18 years old [29], LCH should be classified by single or multiple system involvement and risk organs involvement. As in our case, multisystemic LCH without involvement of risk organs requires systemic therapy to control disease activity, reduce reactivations, and reduce sequelae. Standard treatment is based on vinblastine and corticosteroids and monitor clinical response after the first 6 weeks [29]. PET/CT (positron emission tomography and computed tomography) and organ-specific imaging (CT, US, or MRI) are options based on organs involvement at diagnosis, types of treatment, and patient preference [30].

In conclusion, thyroid involvement in LCH can present with clinical and imaging features that may mimic various thyroid disorders, including thyroiditis or thyroid cancers, which can easily lead to a delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. As the solitary involvement of the thyroid is extremely rare in the pediatric population [31], a comprehensive evaluation of potentially affected organs can help physicians raise concerns about LCH when they observe other systemic involvements. Therefore, an early and accurate diagnosis can be made to provide early and proper treatment.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study, but details from the clinical records are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Rodriguez-Galindo C, Allen CE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2020;135(16):1319–31.

Stålemark H, Laurencikas E, Karis J, Gavhed D, Fadeel B, Henter JI. Incidence of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a population-based study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51(1):76–81.

Li Y, Chang L, Chai X, Liu H, Yang H, Xia Y, Huo L, Zhang H, Li N, Lian X. Analysis of thyroid involvement in children and adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis: An underestimated endocrine manifestation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1013616.

Donadieu J, Rolon MA, Thomas C, Brugieres L, Plantaz D, Emile JF, Frappaz D, David M, Brauner R, Genereau T, et al. Endocrine involvement in pediatric-onset Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis: a population-based study. J Pediatr. 2004;144(3):344–50.

Zhang J, Wang C, Lin C, Bai B, Ye M, Xiang D, Li Z. Spontaneous Thyroid Hemorrhage Caused by Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12: 610573.

Li X, Wang Y, Liu Q, Zeng Q, Fu H, He J, Schmidt-Wolf IGH, Sharma A, Liao F. A rare imaging presentation with multisystemic clinicopathological features of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(35): e34881.

Tawashi K, Khattab K. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the frontal bone with unexpected manifestations: Rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;109: 108580.

Shi JJ, Peng Y, Zhang Y, Zhou L, Pan G. Langerhans cell histiocytosis misdiagnosed as thyroid malignancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(5):1152–7.

Mi B, Wu D, Fan Y, Thong BKS, Chen Y, Wang X, Wang C. Thyroid Langerhans cell histiocytosis concurrent with papillary thyroid carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1105152.

Feng X, Zhang L, Chen F, Yuan G. Multi-System Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis as a Mimic of IgG4-Related Disease: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13: 896227.

Luo L, Li YX. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis and multiple system involvement: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(35):11029–35.

Dursun A, Pala EE, Ugurlu L, Aydin C. Primary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in Thyroid. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). 2020;16(4):501–4.

Munkhdelger J, Vatanasapt P, Pientong C, Keelawat S, Bychkov A. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Thyroid Gland. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15(3):1054–8.

Ozisik H, Yurekli BS, Demir D, Ertan Y, Simsir IY, Ozdemir M, Erdogan M, Cetinkalp S, Ozgen G, Saygili F. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the thyroid together with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Hormones (Athens). 2020;19(2):253–9.

Ben Nacef I, Mekni S, Mhedhebi C, Riahi I, Rojbi I, Nadia M, Khiari K. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Thyroid Leading to the Diagnosis of a Disseminated Form. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2020;2020:6284764.

Liu G, Liu T, Shen C, Zhou L, Ouyang R. A case report. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;45(1):96–101.

He Y, Xie J, Zhang H, Wang J, Su X, Liu D. Delayed Diagnosis of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Presenting With Thyroid Involvement and Respiratory Failure: A Pediatric Case Report. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020;42(8):e810–2.

MAAH, Albisher HM, Al Saeed WR, Almumtin AT, Allabbad FM, MAS. BRAF gene mutations in synchronous papillary thyroid carcinoma and Langerhans cell histiocytosis co-existing in the thyroid gland: a case report and literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019; 19(1):170.

Ismayilov R, Aliyev A, Aliyev A, Hasanov I. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of Thyroid Gland in a Child: A Case Report and Literature Review. Eurasian J Med. 2021;53(2):148–51.

Pileri SA, Grogan TM, Harris NL, Banks P, Campo E, Chan JK, Favera RD, Delsol G, De Wolf-Peeters C, Falini B, et al. Tumours of histiocytes and accessory dendritic cells: an immunohistochemical approach to classification from the International Lymphoma Study Group based on 61 cases. Histopathology. 2002;41(1):1–29.

Schmidt S, Eich G, Geoffray A, Hanquinet S, Waibel P, Wolf R, Letovanec I, Alamo-Maestre L, Gudinchet F. Extraosseous langerhans cell histiocytosis in children. Radiographics. 2008; 28(3):707–726; quiz 910–701.

D’Ambrosio N, Soohoo S, Warshall C, Johnson A, Karimi S. Craniofacial and intracranial manifestations of langerhans cell histiocytosis: report of findings in 100 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(2):589–97.

Laurencikas E, Gavhed D, Stålemark H, van't Hooft I, Prayer D, Grois N, Henter JI. Incidence and pattern of radiological central nervous system Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a population based study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011; 56(2):250-257.

Junewick JJ, Braunreiter C, Fulton B, Olsen A. Imaging Features of Thyroid Involvement by Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. J Diagn Med Sonography. 2009;25(4):212–6.

Iqbal Y, Al-Shaalan M, Al-Alola S, Afzal M, Al-Shehri S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as a painless bilateral swelling of the parotid glands. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26(5):276–8.

Schmidt S, Eich G, Hanquinet S, Tschäppeler H, Waibel P, Gudinchet F. Extra-osseous involvement of Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34(4):313–21.

Saiz E, Bakotic BW. Isolated langerhans cell histiocytosis of the thyroid: A report of two cases with nuclear imaging-pathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4(1):23–8.

Liao F, Luo Z, Huang Z, Xu R, Qi W, Shao M, Lei P, Fan B. Application of <sup>18</sup>F-FDG PET/CT in Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2022;2022:8385332.

Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, Schäfer E, Nanduri V, Jubran R, Egeler RM, Janka G, Micic D, Rodriguez-Galindo C, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(2):175–84.

Goyal G, Tazi A, Go RS, Rech KL, Picarsic JL, Vassallo R, Young JR, Cox CW, Van Laar J, Hermiston ML, et al. International expert consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2022;139(17):2601–21.

Patten DK, Wani Z, Tolley N. Solitary langerhans histiocytosis of the thyroid gland: a case report and literature review. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(2):279–89.

Funding

This manuscript is not funded or supported by any institute or company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yu-Fan Cheng collected data and wrote the manuscript. Ching-Che Wang, Dao-Chen Lin, and Wen-Hui Huang revised the manuscript. Pei-Shan Tsai had made a substantial contribution to the concept and design of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been approved by our Institution Review Board. (IRB number: 23MMHIS119e).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication from the patient’s parents was obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, Y.F., Wang, C.C., Tsai, P.S. et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the thyroid mimicking thyroiditis in a boy: a case report and literature review. BMC Pediatr 24, 66 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-04494-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-04494-0