Abstract

Aim

We evaluated fine motor skills; precision, motor integration, manual dexterity, and upper-limb coordination according to sex and risk stratification in children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL).

Methods

We evaluated twenty-nine children in the maintenance phase aged 6 to 12 years with the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency-second edition (BOT-2), and sex and age-specific norm values of BOT-2 were used to compare our results.

Results

We found lower scores on the upper-limb coordination subtest, p = 0.003 and on the manual coordination composite, p = 0.008, than normative values. Most boys performed “average” on both the subtests and the composites, but girls showed lower scores with a mean difference of 7.69 (95%CI; 2.24 to 3.14), p = 0.009. Girls’ scale scores on the upper-limb coordination subtest were lower than normative values, with mean difference 5.08 (95%CI; 2.35 to 7.81), p = 0.006. The mean standard score difference in high-risk patients was lower than normative on the manual coordination composite, 8.18 (95%CI; 2.26 to 14.1), p = 0.015. High-risk children also performed below the BOT-2 normative on manual dexterity 2.82 (95%CI; 0.14 to 5.78), p = 0.035 and upper limb coordination subtest 4.10 (95%CI; 1.13 to 7.05), p = 0.028. We found a decrease in fine motor precision in children with a higher BMI, rho= -0.87, p = 0.056 and a negative correlation between older age and lower manual dexterity, r= -0.41 p = 0.026; however, we did not find any correlation with the weeks in the maintenance phase.

Conclusions

Fine motor impairments are common in children with ALL in the maintenance phase; it is important to identify these impairments to early rehabilitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL) is the most common cancer in childhood [1]. Advances in chemotherapy treatment in these patients have increased their survival [2, 3]. However, neurotoxicity from the chemotherapy received has also increased the risk of developing peripheral neuropathy in these children, affecting their fine motor skills [4, 5].

Some fine motor skills affected by peripheral neuropathy are weakness of the distal muscles and decreased strength in the upper and lower limbs, alterations in hand coordination, and sensory disturbances [5,6,7].

The above fine motor skills in children are essential for developing physical, social and academic activities [8, 9]. Manual skills are developed in the school stage, as well as some others [10,11,12]. Patients with ALL are often forced to drop out of school for different reasons, including academic ones related to the impairment of these manual skills [13, 14].

Some researchers [15,16,17] have reported fine motor skills impairments in speed and automation of movement and manual dexterity in children and adolescents with ALL in surveillance and in the treatment phase. De Luca et al. (2013) [18] also studied gross and fine motor skills in children with ALL under surveillance; however, they found no differences in their fine motor skills scores when compared to normative values.

Besides, gender differences in fine motor skills have also been described in children with ALL with low-risk and standard-risk ALL in the maintenance phase, and their results showed girls had the most significant deficit than boys except in fine motor integration and fine motor control composite below the average normative data [19].

Some authors have reported girls’ advantages in graphomotor tasks [20] and learning novel tasks [21]. At the same time, other authors have reported that healthy boys outperform better than girls in tasks that require control of objects, such as throwing objects, while prepubertal girls have better manual control when performing novel tasks [22]. Children with ALL, especially those at high risk, do not manage to have manual control even when they reach preadolescence [23].

With everything described above, the importance of evaluating fine motor skills in children with ALL is clear. Therefore, we aimed to describe alterations in fine motor skills (precision, integration, manual dexterity, and coordination of upper limbs) in schoolchildren with ALL during their treatment and if characteristics such as sex, type of risk, age, weight and weeks of treatment were associated with these impairments.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study was performed between July 2019 to August 2022 in the Hospital Infantil de México, Federico Gómez in Mexico City. This study was part of the protocol approved by the Ethics and Research Committee with register number HIM-2019/078. We invited and recruited children with ALL in the Haematology and Oncology Department who received chemotherapy treatment according to the St. Jude total therapy protocol [24]. We obtained informed consent from all parents/legal guardians and children less than 18 years.

Inclusion criteria

Boys and girls with ALL aged 6 to 12 years in the maintenance phase at the time of assessment and high and standard risk were included.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded children with a genetic disorder, pre-existing neurological conditions, those who received cranial radiotherapy, or those who were enrolled in previous or current physical or occupational therapy.

Sample size calculation

We used a mean difference formula with a power of 80% to determine the sample size. Considering a two-tailed hypothesis, the sample calculated was 26 participants. The type of sampling was for convenience of consecutive cases.

Participants selection process

Forty-three children were invited, but eight rejected our invitation because they were uninterested. Thirty-five children with ALL met eligibility criteria, but only 29 were included in the analysis because they completed their fine motor skills assessment (Fig. 1).

Assessment instrument

We used the BOT-2 ® to assess fine motor skills. The BOT-2 fine motor composite consists of four subtests: fine motor precision, fine motor integration, manual dexterity, and upper-limb coordination, grouped into two composites: fine manual control composite and manual coordination composite. Fine manual control encompasses control and coordination of the distal musculature of the hands and fingers during activities like grasping, writing and drawing. In contrast, manual coordination encompasses control and coordination of the arms and hand in object manipulation [25].

The BOT-2 have an internal consistency between 0.73 and 0.89 in both composites and subtests, with interrater reliability coefficients of 0.98 and 0.99 for the subtests [25].

Measures and procedures

Once the children were recruited, a physiotherapist with five years of professional practice and training in managing the BOT-2 applied and analysed the tests and subtests to assess fine motor skills. Each child was evaluated individually and required about 20–30 min to complete the subtests.

Participants were required to use their dominant drawing hand for all subtests except the upper limb coordination subtest, performed by the dominant throwing hand according to the BOT-2 manual.

Subsequently, children’s clinical characteristics such as sex, age, weeks on the maintenance phase at assessment, weight, height and risk stratification (standard, high), weight z-score classification and comorbidities were registered. Anthropometric measures were determined by a trained nutritionist using a Medical beam scale for weight, and Stadiometer Nuevo León S.A de C.V for height. Weight z-score classification was determined according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Finally, we represented scale and standard scores for composites and subtests in descriptive categories ranging from “Well-below average” to “Well-above average.“ The BOT-2 manual defines the “Average” category as ± 1 standard deviation of the scale or standard score [25]. Additionally, reported total point scores according to age- and sex-specific scale scores (X = 15; SD = 5) and standard scores (X = 50; SD = 10) according to the BOT-2 normative reference [25].

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilks test was used to determine the data normality. Mean and standard deviation (± SD) were used to represent our quantitative variables (age, weight, height and weeks on maintenance phase) and frequencies relatives and absolutes were used to describe the qualitative variables (stratification risk, comorbidities, z score classification).

We used a one-sample independent t-test to compare the reference value in BOT-2 subtests and composite scores and the U-Mann Whitney test to compare differences between sex and risk stratification. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the association between BOT-2 subtests, composite scores, weeks on maintenance phase and age. The Spearman correlation coefficient was also calculated to determine the association between BOT-2 subtests and composite scores and qualitative variables (sex, risk stratification and weight z-score classification).

We compare the mean score standard differences between the scholarship included and the BOT-2 normative with 95% confidence intervals and significance level < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using the Stata program version 15.1 for Windows (StataCorp, Texas, USA), and the graphs were made using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

We included 29 children aged 7.9 ± 1.29 years, and 16 were boys (55.2%). Clinical characteristics showed that boys had greater body weight (p > 0.05) and girls were stratified with a higher risk of disease (p = 0.96). In addition, only one girl had a history of COVID-19, and another had lower limb neuropathy. Therefore, four children had a relapse history, and three had high-risk ALL (two boys and one girl) (Table 1).

Fine manual control and manual coordination composites

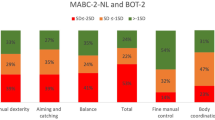

The descriptive categories for fine manual control and manual coordination composites are shown in Fig. 2a. Most of the children had an “average” performance; however, almost 30% of them were categorised as “below average” or “well-below average” performance, and the manual coordination composite had the highest proportion of children with “below average”.

The mean standard score difference on BOT-2 composites according to sex showed that girls had lower scores than the age-match norm on manual coordination with a mean difference of 7.69 (95% CI 2.24 to 13.14), p = 0.009. The mean standard score difference in high-risk patients was significantly lower than standard-risk patients on the age-matched norm on the manual coordination composite, with a mean difference of 8.18 (95% CI 2.26 to 14.1), p = 0.015. Fine motor control and fine motor function were not statistically significant, with p > 0.05 (Fig. 3a and b).

(a) Mean differences in BOT-2 composites according to sex. (b) Mean differences in BOT-2 composites according to risk stratification. *Statistically significant (p < 0.05). BOT-2 Standard score mean = 50 (SD = 10) [25]

Although differences previously mentioned compared to the age-match norm, we did not find statistically significant differences between boys and girls in our sample, nor between high-risk and standard-risk stratification (p > 0.05).

We found no correlation between BOT-2 subtests scale scores nor composites standard scores and the weeks on the maintenance phase, risk stratification, nor Z score > 1 (p > 0.05).

BOT-2 subtests

The descriptive categories for fine motor precision, integration and manual dexterity, and upper-limb coordination subtests are shown in Fig. 2b. Most of the children had an “average” performance; however, almost 30% of them were categorised as having “below average” or “well-below average” performance on manual dexterity and upper-limb coordination. The manual dexterity subtest had the highest proportion of children “below average”.

ALL children included performed more poorly compared to the standardised age-match BOT-2 norm on manual dexterity with a mean difference of 1.48 (95% CI -3.30 to 0.34), p = 0.057, but this value was not statistically significant. However, on upper-limb coordination subtests of the BOT-2 scale scores were significantly lower in ALL studied children with a mean difference of 3.42 (95% CI 1.59 to 5.23), p = 0.0031. Furthermore, girls’ scale scores on the upper-limb coordination subtest were significantly lower than the age-match BOT-2 norm with a mean difference of 5.08 (95% CI 2.35 to 7.81), p = 0.006 (Fig. 4a).

(a) Mean differences on BOT-2 subtests according to sex. (b) Mean differences on BOT-2 subtests according to risk stratification. *Statistically significant (< 0.05). BOT-2 Scale Score mean = 15 (SD = 5) [25]

Regarding risk stratification, high-risk children performed below the BOT-2 norm for age in manual dexterity with a mean difference of 2.82 (95% CI 0.14 to 5.78), p = 0.035 (Fig. 4b). In addition, standard-risk and high-risk children had lower scores on the upper limb coordination subtest than the BOT-2 norm; mean differences were 3.0 (95%CI 0.69 to 5.31), p = 0.030 and 4.10 (95%CI 1.13 to 7.05), p = 0.028 respectively (Fig. 4b).

Fine motor precision and fine motor integration subtests were not different from the norm data (p > 0.05). We did not find differences between boys and girls, nor between high-risk and standard-risk patients.

We found a negative correlation between age and manual dexterity scale score (r= -0.41), p = 0.026 (Online Resource 1). We did not find a significant correlation between weight z-score classification and the subtests scale score; however, we found a decrease in fine motor accuracy in children with the highest BMI (rho= -0.87), p = 0.058.

Discussion

The main findings of our study were that manual coordination composite in children with ALL evaluated was the most affected fine motor skills as well as upper limb coordination and manual dexterity domains in girls and high-risk children.

Fine motor skills are particularly important when children are at the school stage, where they spend more than half of the day completing academic tasks that require the integrity of these skills [26]. In particular, the completeness of hand coordination and its subtests allow for goal-directed activities involving reaching, grasping, and hand coordination to pick up small objects and for self-care activities such as holding eating utensils. In older children, when these skills are altered, the quality of writing may be affected, leading to poor student performance [27].

Additionally, alterations in fine motor skills could affect the social, academic, communication, and coping environment of children with cancer [13, 28,29,30].

Our study showed lower scores in girls in upper limb coordination, which are relevant skills for catching and throwing objects; however, this finding differs from that reported by Hamari L et al. (2020), [29] who described better scores in girls in manual dexterity and coordination of upper limbs when they were evaluated at 6, 12, and 30 months (p > 0.05). An explanation for these differences is that, in our study, most of the affected girls were classified as high-risk. In contrast, the affected girls reported in Hamari’s study had low-risk or standard risk. We consider this finding relevant because children with high-risk ALL who receive frequent, high doses of chemotherapeutic agents have been reported to be at increased risk of developing fine motor deficits; however, our study could not demonstrate this [23, 30].

In addition, the children evaluated in our study were older than those included by Hamari et al. [29], who included children aged 5.62 ± 1.11 years. This aspect is relevant since school-age children, like those in our research, perform tasks that require more complex manual and upper limb coordination than younger children, which, in addition to making these motor deficiencies more evident, could explain the negative correlation found in our study between older age and lower manual dexterity.

On the other hand, sex has been described as another factor in explaining motor skills in boys, which can somehow explain the poor performance of our girls due to gender stereotypes about the type of games and activities in which they should participate [20].

Besides, our study showed that children with higher BMI had poor fine motor precision (rho= -0.87), p = 0.058. This finding has already been reported; an example of this is the study of Gentier et al. (2013), [31] who reported worse scores in fine motor precision and manual dexterity according to their weight increase in patients aged 7–13 years. Our results suggest a trend towards poorer motor performance in overweight patients compared to normal-weight patients; however, our sample size was small.

Our study has strengths, such as identifying fine motor skills impairment in older girls with ALL patients with high risk during the maintenance phase. However, despite the strengths of our study, we also recognise several limitations related to the small sample size, the cross-sectional design, and its consequent selection bias; therefore, we did not search for a correlation between chemotherapy and fine motor impairments.

This study highlighted the importance of evaluating fine motor skills in children with cancer, specifically those girls with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. The early identification of deterioration in manual coordination and its upper limbs is essential for the treating physicians to refer children promptly for rehabilitation. This timely rehabilitation will allow these children to achieve their social, academic and recreational activities necessary for optimal growth and development.

Conclusion

In the maintenance phase, fine motor impairments are common in children with ALL, and their identification could facilitate early rehabilitation.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ALL:

-

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia

- BOT-2:

-

Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency- second edition

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Malard F, Mohty M. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. The Lancet. 2020;395:1146–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33018-1.

Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, Camitta BM, Gaynon PS, Winick NJ, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: a report from the children’s oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1663–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8018.

Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Al ESEER, Cancer Statistics. Review, 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations). National Cancer Institute 2009. http://serr.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/ (accessed May 9, 2022).

Lehtinen SS, Huuskonen UE, Harila-Saari AH, Tolonen U, Vainionpää LK, Lanning BM. Motor nervous system impairment persists in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2002;94:2466–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10503.

Ramchandren S, Leonard M, Mody RJ, Donohue JE, Moyer J, Hutchinson R, et al. Peripheral neuropathy in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Peripheral Nerv Syst. 2009;14:184–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8027.2009.00230.x.

Gomber S, Dewan P, Chhonker D. Vincristine induced neurotoxicity in cancer patients. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:97–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-009-0254-3.

Reinders-Messelink HA, Schoemaker MM, Snijders TAB, Göeken LNH, Bökkerink JPM, Kamps WA. Analysis of handwriting of children during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37:393–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpo.1216.

Cantell MH, Smyth MM, Ahonen TP. Clumsiness in adolescence: Educational, motor, and social outcomes of motor delay detected at 5 years. Adapted Phys Activity Q. 1994;11:115–29. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.11.2.115.

Schoemaker MM, Kalverboer AF. Social and affective problems of children who are clumsy: how early do they begin? Adapted Phys Activity Q. 1994;11:130–40. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.11.2.130.

Geertsen SS, Thomas R, Larsen MN, Dahn IM, Andersen JN, Krause-Jensen M, et al. Motor skills and exercise capacity are associated with objective measures of cognitive functions and academic performance in preadolescent children. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161960. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161960.

Moore IM, Lupo PJ, Insel K, Harris LL, Pasvogel A, Koerner KM, et al. Neurocognitive predictors of academic outcomes among childhood leukemia survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:255–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000293.

Barnes MA, Raghubar KP. Mathematics development and difficulties: the role of visual-spatial perception and other cognitive skills. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1729–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24909.

Tremolada M, Taverna L, Bonichini S, Basso G, Pillon M. Self-esteem and academic difficulties in preadolescents and adolescents healed from paediatric leukaemia. Cancers (Basel). 2017;9:55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers9060055.

Donnan BM, Webster T, Wakefield CE, Dalla-Pozza L, Alvaro F, Lavoipierre J, et al. What about School? Educational Challenges for children and adolescents with Cancer. Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist. 2015;32:23–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2015.9.

Goebel AM, Koustenis E, Rueckriegel SM, Pfuhlmann L, Brandsma R, Sival D, et al. Motor function in survivors of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with chemotherapy-only. Eur J Pediatr Neurol. 2019;23:304–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.12.005.

Sabarre CL, Rassekh SR, Zwicker JG. Vincristine and fine motor function of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Can J Occup Ther. 2014;81:256–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417414539926.

Hockenberry M, Krull K, Moore K, Gregurich MA, Casey ME, Kaemingk K. Longitudinal evaluation of fine motor skills in children with leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;29:535–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e3180f61b92.

De Luca CR, McCarthy M, Galvin J, Green JL, Murphy A, Knight S, et al. Gross and fine motor skills in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Dev Neurorehabil. 2013;16:180–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2013.771221.

Hanna S, Elshennawy S, El-Ayadi M, Abdelazeim F. Investigating fine motor deficits during maintenance therapy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28385.

Moser T, Reikerås E. Motor-life-skills of toddlers – a comparative study of norwegian and british boys and girls applying the early Years Movement Skills Checklist. Eur Early Child Educ Res J. 2016;24:115–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2014.895560.

Flatters I, Hill LJB, Williams JHG, Barber SE, Mon-Williams M. Manual Control Age and Sex differences in 4 to 11 Year Old Children. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e88692. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088692.

Escolano-Pérez E, Sánchez-López CR, Herrero-Nivela ML. Early environmental and biological influences on Preschool Motor Skills: implications for early Childhood Care and Education. Front Psychol. 2021;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.725832.

Livshits Z, Rao RB, Smith SW. An Approach to Chemotherapy-Associated toxicity. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32:167–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2013.09.002.

Omar AA, Basiouny L, Elnoby AS, Zaki A, Abouzid M. St. Jude Total Therapy studies from I to XVII for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a brief review. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2022;34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43046-022-00126-3.

Bruininks R, Bruininks B. Bruininks-Oseretsky test of motor profienciency. 2nd ed. Minneapolis: NCS Pearson; 2005.

McHale K, Cermak SA. Fine Motor Activities in Elementary School: preliminary Findings and Provisional Implications for Children with Fine Motor problems. Am J Occup Therapy. 1992;46:898–903. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.46.10.898.

Chase CI. Essay test scoring: Interaction of relevant variables. J Educ Meas. 1986;23:33–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3984.1986.tb00232.x.

Tremolada M, Taverna L, Bonichini S, Pillon M, Biffi A. The developmental pathways of preschool children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: communicative and social sequelae one year after treatment. Children. 2019;6:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6080092.

Hamari L, Lähteenmäki PM, Pukkila H, Arola M, Axelin A, Salanterä S, et al. Motor Performance in Children diagnosed with Cancer: a longitudinal observational study. Children. 2020;7:98. https://doi.org/10.3390/children7080098.

Buizer AI, de Sonneville LMJ, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Veerman AJP. Behavioral and educational limitations after chemotherapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia or Wilms tumor. Cancer. 2006;106:2067–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21820.

Gentier I, D’Hondt E, Shultz S, Deforche B, Augustijn M, Hoorne S, et al. Fine and gross motor skills differ between healthy-weight and obese children. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:4043–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.08.040.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Research Department of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez for the financial support for purchasing the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency-second edition (BOT-2) ® assessment tool.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tejeda-Castellanos: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing- original draft, writing- review & editing, visualization; Sánchez-Medina: investigation, resources, writing- review & editing, project administration; Márquez-González: resources, writing- review & editing; Alaniz-Arcos: writing- review & editing; Ortiz-Cornejo: writing- review & editing; Brito-Suarez: investigation, writing- review & editing; Juárez-Villegas: writing- review & editing, visualization; Gutierrez-Camacho: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, supervision, writing- original draft, writing- review & editing, visualization, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Statements and declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Ethics approval

This study was part of the protocol approved by the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez’s Ethics and Research Committee with register number HIM-2019/078. Therefore, this study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

We obtained informed consent from all parents/legal guardians and children less than 18 years.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tejeda-Castellanos, X., Sánchez-Medina, C.M., Márquez-González, H. et al. Impairments in fine motor skills in children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr 23, 513 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-04316-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-04316-3