Abstract

Background

Hyponatremia is a serious problem that leads to substantial increases morbidity and mortality in critically ill children. The identification of risk factors, implementation of preventive measures, and timely diagnosis and management are crucial to reduce adverse events related to hyponatremia. Despite the higher burden of the problem in Ethiopia, evidence related to the risk factors for hyponatremia among children in Ethiopia is limited; in particular, no study has been identified in eastern Ethiopia. Therefore, we aimed to determine the magnitude of hyponatremia and its associated factors in children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit at the Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital.

Methods

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted using 422 medical records of pediatric patients admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit at Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital from January 2019 to December 2022. Medical records were reviewed to collect data. Data were analyzed using a statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 26. A binary logistic regression model with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to identify factors associated with the outcome variable. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The magnitude of hyponatremia was 39.1% (95% CL: 34.4–43.8%). The age of the child (aOR = 2.37;95% CL:1.31–4.31), diagnosis of sepsis (aOR = 2.33; 95% CL:1.41–3.84), surgical procedures (aOR = 2.39; 95% CL:1.26–4.56), nutritional status (aOR = 2.60; 95% CL:1.51–4.49), and length of hospital stay (aOR = 3.04; 95% CL: 1.73–5.33) were factors significantly associated with hyponatremia.

Conclusions

Four out of ten children admitted to pediatric intensive care units had hyponatremia. Hyponatremia was significantly associated with the age of the child, malnutrition, sepsis, surgical procedures, and length of hospital stay. To reduce the burden of hyponatremia and associated mortality, attention should be focused on improving the care of malnourished children, and those with sepsis, and the quality of postoperative monitoring services. Moreover, intervention strategies aimed at reducing the burden of hyponatremia should target the identified factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hyponatremia is defined as a plasma sodium level of less than 135 mmol/L. It is the most common electrolyte disorder encountered in clinical practice and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1,2,3]. Hyponatremia can cause neurological dysfunction, decreased mental function, cerebral edema, osteoporosis, fractures, gait disturbances, and falls [4,5,6]. Hyponatremia affects up to 22% of hospitalized patients and up to 67.2% of hospitalized in pediatric intensive care units ( PICUs) [7]. Hyponatremia accounts for 32.5% of mortality after admission to the PICUs. However, early diagnosis and treatment of hyponatremia can reduce morbidity and hospitalization times [6, 8]. Underlying medical conditions increase the risk of moderate to severe hyponatremia and death [3, 9,10,11].

Hyponatremia is associated with overall poor outcomes in pediatric populations [11]. The problems associated with delays in the provision of appropriate care can result in seizures, acute psychosis, permanent brain damage, and brainstem herniation, leading to coma and death [3, 6, 12, 13]. Appropriate treatment of pediatric hyponatremia necessitates knowledge of the etiology of hyponatremia; the child’s effective circulating volume, hemodynamic stability, the severity of symptoms, and the duration and rate of sodium concentration change [13]. Low sodium levels should be treated based on the underlying cause, and treatment with hypertonic sodium, fluid restriction, and treatment of the underlying disease leads to complete recovery [14, 15].

Hyponatremia has multifactorial causes and can be associated with salt and water loss [1, 15, 16]. Free water consumption, and underlying conditions that cause no osmotic stimulation for the synthesis of vasopressin [16]. Children are especially susceptible to clinical hyponatremia and hyponatremia encephalopathy and have a poor prognosis if treatment is not started on time [17, 18]. Critically ill patients admitted to the PICU with underlying medical conditions have abnormal sodium and potassium levels [19].

The most frequent electrolyte abnormalities are hyponatremia associated with central nervous system disorders (52.9%), gastrointestinal disorders (17.6%), and sepsis (11.8%) [7, 20]. Moreover, malaria, gastroenteritis, pneumonia, malnutrition, neonatal sepsis [21], postsurgical status, prolonged PICU stay, fluid intake, and mechanical ventilation were other significantly associated factors [22, 23]. Hyponatremia can increase the length of hospital stay by 1–2 days and correlates with an increased risk of intensive care unit admission [22, 24].

Preventive measures for hyponatremia include checking plasma sodium levels 1–2 weeks after starting thiazide, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) therapy, especially in patients at high risk for hyponatremia; avoiding hypotonic fluids and thiazides in people with high fluid or low protein intake and measuring plasma sodium levels in all hospitalized patients on admission [25, 26]. Clinicians should monitor daily plasma sodium levels in patients with hyponatremia or in those at high risk [25]. Furthermore, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends the use of isotonic fluids for the maintenance of intravenous fluids in patients aged 28 days to 18 years to reduce the risk of developing hyponatremia, which can occur with hypotonic fluids [27].

Few studies had investigated the burden of hyponatremia in low and middle-income countries, particularly Ethiopia where many pediatric patients are admitted to the PICUs. The lack of sodium level studies in these settings may lead to inappropriate treatments, especially with supportive fluid therapy, which should consider electrolyte concentrations [14, 28]. Early recognition of hyponatremia and its associated factors may be enhanced by supportive therapy to improve outcomes. Studies investigating the magnitude and associated factors in children admitted to the PICUs are warranted. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the magnitude of hyponatremia and address the associated factors among patients admitted to the PICU at Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital.

Methods

Study setting, design, and population

This retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted at Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital in eastern Ethiopia. This is a teaching referral hospital at Haramaya University, located 526 km from Addis Ababa. This facility provides health services for an estimated six million people in eastern Ethiopia. The hospital was established during the Italian invasion and became a teaching and referral hospital at Haramaya University in 2014. There are different wards and clinics within the hospital, including the pediatric ward, PICU, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), internal medicine, surgery, gynecology, and obstetrics. This study was conducted among children admitted to the PICU between January 2019 and December 30, 2022. All medical records of children admitted to the PICU between January 2019 and December 2022 were the source population. However, the medical records of children with pre existing electrolyte disturbances, such as chronic kidney disease, and medical records without electrolyte determination were excluded from this study.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

The sample size was computed using a single proportion formula by considering 50% hyponatremia as a proportion (P) because no study was previously conducted in Ethiopia. We considered the following assumptions: 95% confidence interval (CI) and marginal error of 5%. The calculated sample size was 384; we added a 10% nonresponse rate, and the final sample size was 422. A simple random sampling technique was used to select participants. A total of 628 patients were admitted to the PICU of the hospital from January 2019 to December 2022. Of these, 422 were included in the study using computer-generated simple random sampling techniques and fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Data collection

Data were collected by two BSc nurses and supervised by two senior MSc nurses. Data were collected from medical chart review using a validated data abstraction checklist adapted from previous studies [10, 21, 22]. The tools contain information on the sociodemographic factors of the child such as; age, sex, and place of residence. Serum electrolyte profile; sodium. Admission diagnosis; central nervous system disorders, cardiovascular disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, endocrine disorders, respiratory disorders, postsurgical cases, renal disorders, sepsis, severe acute malnutrition, poisoning, and hematologic disorders. Hospital interventions; surgery, hyponatremia fluid therapy, mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, and outcomes. Serum electrolyte levels were measured following the standard operating procedure. Serum Sodium value: Normal Range: 135 to 145 mmol/L, Hyponatremia: <135 mmol/L Hypernatremia: >145 mmol/L [17]. Weight for length/height, between 3SD and 2SD – normal and below 2SD- malnourished; BMI for age, between 3SD and 2SD – normal and below 2SD- malnourished.

Data quality assurance

To ensure the quality of data, a pretest was conducted with 5% of the sample size at Dil Chora Hospital’s pediatric intensive care unit. Two days of training were provided to all data collectors and supervisors. The data collection process was closely supervised. Supervisors and principal investigators checked the completeness of each questionnaire daily. During data cleaning, a logical checking technique was employed to identify errors. Finally, double data entry was performed to verify data consistency.

Data processing and statistical analysis

The collected data were entered into Epi Data 4.6 and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26. Frequency, mean and proportion were used for the descriptive analysis. A binary logistic regression model was used to determine the factors associated with the outcome variable. All variables with p ≤ 0.25 in the bivariable logistic regression were entered into the final multivariable analysis to control confounders. The goodness of fit of the model was tested using the Hosmer‒Lemeshow test (> 0.05). A multicollinearity test was performed to determine the correlation between the independent variables using variance inflation factors (VIF > 10). The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

The medical records of 422 children were reviewed. The age of the study subjects ranged from 29 days to 15 years and the mean and standard deviation (SD) age was 3 ± 3.7 years. Of these 422 participants, 187 (44.3%) were aged less than 5 years. Among the study participants, 243 (57.6%) were male while the remaining 179 (42.4%) were female. Nearly two thirds of the study participants, 251(59.5%) were from urban areas [Table 1].

Magnitude of hyponatremia

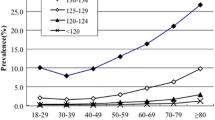

Of the 422 medical records reviewed, 165 (39.1%) had hyponatremia with 95% CL: 34.4–43.8%). The mean sodium concentration was 136 mmol/l. Two hundred (47.4%) patients had a normal range of sodium concentration [Fig. 1].

Common morbidities at admission

Nearly half of the patients, 206 (48.8%) showed altered levels of consciousness. More than one-third of the patients, 176 (41.7%) had central nervous system disorders at admission, with meningitis accounting for 146 (82.9%) of the cases. More than one-fifth of the study participants 97 (22.9%) were diagnosed with sepsis at admission and 29 (29.9%) had severe sepsis. Only 44 (10.4%) participants had cardiovascular disorders, and heart failure accounted for 36 (81.8%). One-third of the patients, 119 (28.2%) had gastrointestinal related problems. Only 3 (0.7%) had endocrine disorders of which 2 (66.7%) had diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and the remaining 1(33.3%) had hypoglycemia. Four (0.9%) had poisoning [Table 2].

Hospital interventions

Regarding hospital stay, the patients stayed in the hospital for an average of 12 days. One-third 154 (36.5%) of the children stayed for 1 to 2 weeks. Of 422 patients, 69 (16.4%) underwent surgery, and 22 (31.9%) underwent laparotomy [Table 3].

Factors associated with hyponatremia

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that; the age of the child, Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC), sepsis, surgery, and duration of hospital stay were significantly associated with hyponatremia. Children aged less than 5 years were 2.37 times (aOR = 2.37; 95% CI; 1.31–4.31) more likely to develop hyponatremia than children aged 5 and 15 years. Severely malnourished children who were measured by MUAC were 2.60 times (aOR = 2.6; 95% CI: 1.51–4.49) more likely to be hyponatremic than well-nourished children. Moreover, pediatric patients who were diagnosed with sepsis were 2.33 times (aOR = 2.32; 95% CI: 1.41–3.83) more likely to suffer from hyponatremia than their counterparts. Furthermore, children who underwent surgical procedures and were admitted to the PICU were 2.39 times (aOR = 2.39; 95% CI: 1.26–4.56) more likely to develop hyponatremia than those who did not undergo surgical procedures. In addition, patients who stayed in the PICU for more than 2 weeks were 3.04 times (aOR = 3.04; CI 1.73–5.33) more likely to develop hyponatremia than those who stayed for less than a week [Table 4].

Discussion

Hyponatremia in critically ill children leads to a substantial increase in morbidity and mortality [1,2,3]. Evidence suggested that a delay in recognition and treatment of hyponatremia can lead to poor prognosis [17, 18]. Identification of risk factors, implementation of preventive measures, and timely diagnosis with management are crucial to minimize adverse events related to hyponatremia. This study aimed to assess the magnitude of hyponatremia and its associated factors among children admitted to the PICU at the Hiwot Fana Comprehensive Specialized University Hospital. The magnitude of hyponatremia was 39.1% (95% CI: 34.4–43.8%). In multivariable analysis, age less than five years, MUAC, diagnosis of sepsis, undergoing surgical procedures, and length of hospital stay were identified as independently associated with hyponatremia.

The findings of this study are consistent with those studies conducted in Egypt (36%) [29], and Nigeria (39.6%) [30]. However, this study is inconsistent with a study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (16.7%) [22]. This variation could be due to the difference in the comorbidities that the child was admitted with, and the method of serum sodium measurement. Most laboratories use a direct measurement of sodium. This could also be hyponatremia in critically ill children, which may reflect an endogenous state of sodium dysregulation, iatrogenic causes, or both [19].

Furthermore, the present findings indicate that critically ill children aged less than 5 years were two times more likely to have hyponatremia than those aged 5–15 years. This finding is supported by studies conducted in Taiwan [31], and Nigeria [30]. This could be because younger children are at high risk for the development of hyponatremia due to their small body size, hence their high water concentration, lower glomerular filtration rate, reduced proximal tubular reabsorption of sodium, and increased arginine vasopressin levels in response to illness [32].

In addition, malnourished children are three times more likely to develop hyponatremia than their counterparts. This finding is in line with studies conducted in India [33], Bangladesh [34], and Kenya [21]. This may be due to severely malnourished children; most children have excess total body sodium despite low serum sodium levels thus, masking sodium overload [35].

Moreover, this study found that a length of hospital stay of more than two weeks was three times increase the risk of hyponatremia. This finding is in agreement with studies conducted in Saudi Arabia [29, 36]. This might be explained by the likelihood of acquiring hospital-acquired infections and receiving a large amount of fluid during the long hospital stay. Furthermore, the more patients stayed in the hospital, the more likely they were to be complicated and prone to take different drugs that can even cause hyponatremia [37].

Furthermore, children diagnosed with sepsis were twice as at risk of hyponatremia. These findings are consistent with those of a study conducted in India [2]. This could be due to sepsis resulting in dilution of the extracellular space with retained exogenous fluid secondary to disrupted cellular membrane integrity as well as the development of renal insufficiency which may lead to hyponatremia [38].

In addition, patients who underwent surgery were twice at risk of developing hyponatremia. This is comparable with studies conducted in the United States of America [36], Croatia [39], and India [40]. This may be because surgical patients receive a large amount of fluid both pre and postoperatively. Furthermore, postoperative hyponatremia is provoked by surgical stress, which causes a syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone levels in almost everyone, often promoting water retention for several days [41].

Conclusions

Four out of ten children admitted to pediatric intensive care unit had hyponatremia. Hyponatremia was found to be significantly associated with the age of child, malnutrition, sepsis, surgical procedures, and longer length of hospital stay in the pediatric intensive care unit.

To reduce the burden of hyponatremia and associated mortality, attention should be directed toward improving the care of malnourished children, and those with sepsis, and the quality of postoperative monitoring services.

In numerous occasions, hyponatremia is found incidentally when serum electrolytes are obtained during clinical evaluation for severly ill patients. So early diagnosis of more risk patients for the occurrence of hyponatremia and early intervention is very important.

Moreover, intervention strategies aimed at reducing the burden of hyponatremia should target the identified factors.

Data Availability

Data will be available upon request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ADH:

-

Anti-diuretic hormone

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- DKA:

-

Diabetic ketoacidosis

- MUAC:

-

Mid-upper arm circumference

- PICU:

-

Pediatric intensive care unit

- SIADH:

-

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone

- IHREC:

-

Institutional Health Research Ethical Committee

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences.

References

Zieg J. Pathophysiology of hyponatremia in children. Front Pead. 2017;5:213.

Padhi R, Panda BN, Jagati S, Patra SC. Hyponatremia in critically ill patients. Indian J Crit care medicine: peer-reviewed official publication Indian Soc Crit Care Med. 2014;18(2):83.

Adrogué HJ. Consequences of inadequate management of hyponatremia. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25(3):240–9.

Patterson JH. The impact of hyponatremia. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 2011;31(5P2):5S–8S.

Mokhtari M, Koochak M, Goharani R, Miri M, Araghi P. Frequency of hyper-and hypo-natremia in patients admitted in the ICU & comparison of their association with mortality. Pejouhesh dar Pezeshki. 2009;33(3).

Bennani S, Abouqal R, Zeggwagh A, Madani N, Abidi K, Zekraoui A, et al. Incidence, causes and prognostic factors of hyponatremia in intensive care. La Revue de Medecine Interne. 2003;24(4):224–9.

Al-Sofyani KA. Prevalence and clinical significance of hyponatremia in pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2019;8(03):130–7.

Ramzan S, Zaffar J, Mazhar S. Hyponatremia among critically ill children admitted to pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). J Med Physiol Biophys. 2017;37:35–9.

Lehtiranta S, Honkila M, Anttila S, Huhtamäki H, Pokka T, Tapiainen T. The incidence, hospitalizations, and deaths in acutely ill children with dysnatraemias. Acta Pediatrica. 2022;111(8):1630–7.

Balaji J. Clinical profile, etiology, management and outcome of serum electrolyte disturbances in children admitted in pediatric intensive care unit in a tertiary care center. Stanley Medical College, Chennai; 2016.

Elliman MG, Vongxay O, Soumphonphakdy B, Gray A. Hyponatraemia in a lao pediatric intensive care unit: prevalence, associations, and intravenous fluid use. J Pediatr Child Health. 2019;55(6):695–700.

Peri A. Morbidity and mortality of hyponatremia. Disorders of Fluid and Electrolyte Metabolism. 2019;52:36–48.

Edmonds ZV. Pathophysiology, impact, and management of hyponatremia. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(S4):1–S5.

AZ. SMT. Hyponatraemia in Children: Evaluation and Management [Internet], Waltham MA. Available from: https://www.uptodate.compklibresourceshealthwagovau/contents/hyponatremia-in-children-evaluation-and-management UpToDate; 2023 [cited 10/03/2023].

Sahay M, Sahay R, Hyponatremia. A practical approach. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;18(6):760.

Horacio JA, Nicolaos EM, Hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(21):1581–9.

McInerny TK. American Academy of Pediatrics textbook of pediatric care. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017.

Moritz ML, Ayus JC. New aspects in the pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment of hyponatremic encephalopathy in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1225–38.

Luu R, DeWitt PE, Reiter PD, Dobyns EL, Kaufman J. Hyponatremia in children with bronchiolitis admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit is associated with worse outcomes. J Pediatr. 2013;163(6):1652–6. e1.

Paidy AR, Thapar RK, Gupta RK. Electrolyte disturbances in critically ill children admitted to the pediatric tertiary care center. J Evol Med Dent Sci (JEMDS). 2017;6:3269–73.

Ibinda F, Zarnack H-C, Newton CR. Sodium disturbances in children admitted to a kenyan hospital: magnitude, outcome and associated factors. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0161320.

Elala G, Shimelis D. Patterns of electrolyte abnormalities in children 0–15 years of age admitted to pediatric emergency and intensive care units of a tertiary hospital. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2018;17(2):12–6.

Sachdev A, Pandharikar N, Gupta D, Gupta N, Gupta S, Venkatraman ST. Hospital-acquired hyponatremia in the pediatric intensive care unit. Indian J Crit Care Medicine: Peer-reviewed Official Publication Indian Soc Crit Care Med. 2017;21(9):599.

Kiran VA, Chaudhary R. Clinical Profile and Outcome of children with serum Electrolyte Abnormalities in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology. 2021:3914–20.

Henry DA. Hyponatremia. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):ITC1–ITC16.

Egger C, Muehlbacher M, Nickel M, Geretsegger C, Stuppaeck C. A review on hyponatremia associated with SSRIs, reboxetine, and venlafaxine. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2006;10(1):17–26.

Costlow L. Maintenance intravenous fluids in children: AAP provides recommendation. Am Family Phys. 2019;100(4):251.

Hoorn EJ, Zietse R. Diagnosis and treatment of hyponatremia: compilation of the guidelines. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(5):1340–9.

Ali SH, Mohammed MM, Youssef RS. The pattern of Electrolyte Imbalance in critically Ill Children admitted in Pediatric Emergency Unit at Sohag University Hospital. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2021;82(2):276–81.

Uhegbu K, Orji I, Uhegbu V, Osuji K, Eke E. Pattern of electrolyte profile among admitted children (1–18 years) at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. Medico Res Chronicles. 2020;7(1):06–12.

Yen C-W, Yu M-C, Lee J. Serum electrolyte abnormalities in pediatric patients presenting to an emergency department with various diseases: age-related differences. Pediatr Neonatology. 2022;63(6):575–81.

Haycock GB, Aperia A. Salt, and the newborn kidney. Pediatr Nephrol. 1991;5:65–70.

Kumar D, Rao SK, Singh TB. Clinico-biochemical profile of sick children with severe acute malnutrition. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(5):2269.

Shahrin L, Chisti MJ, Huq S, Nishath T, Christy MD, Hannan A, et al. Clinical manifestations of hyponatremia and hypernatremia in underf ive diarrheal children in a diarrhea hospital. J Trop Pediatr. 2016;62(3):206–12.

Ashworth AKS, Jackson A, Schofield C. Guidelines for the inpatient treatment of severely malnourished children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

Keating O, Hale AT, Smith AA, Jimenez V, Ashraf AP, Rocque BG. Hyponatremia after craniotomy in children: a single-institution review. Child’s Nerv Syst. 2022:1–7.

Zheng Y, Zheng FP, Li H. [The prevalence and causes of hyponatremia in hospitalized patients]. Zhonghua nei ke za zhi. 2020;59(1):29–34.

Hannon RJ, Boston VE. Hyponatraemia and intracellular water in sepsis: an experimental comparison of the effect of fluid replacement with either 0.9% saline or 5% dextrose. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25(4):422–5.

Pogorelić Z, Lukšić B, Ninčević S, Lukšić B, Polašek O. Hyponatremia as a predictor of perforated acute appendicitis in the pediatric population: a prospective study. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(10):1816–21.

Shrestha AL, Jehangir S, Thomas RJ. Hyponatremia among postoperative children administered with hypotonic fluids in a Tertiary Care Hospital: a descriptive cross-sectional study. JNMA: J Nepal Med Association. 2021;59(243):1131.

Ayus JC, Arieff AI. Brain damage and postoperative hyponatremia: the role of gender. Neurology. 1996;46(2):323–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank Haramaya University for its technical support. We would also like to extend our gratitude to the head and staff of Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, the data collectors, and the supervisors for their collaboration.

Funding

This work was technically (non financial) supported by Haramaya University, Ethiopia. This organization had no role in the selection of participants, data collections, analysis, conclusions, and interpretations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YB, TY, and AD made a substantial contribution to the conception, data acquisition, the study design, analysis, and interpretation of the findings. AM, FM, BDH, AA, GT, MK, and FW contributed to the interpretation of the data, writing, and revising of the manuscript. AA and MK drafted the manuscript. All the authors have carefully revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before starting the data collection process, the study protocol was approved by Haramaya University, College of Health and Medical Sciences Institution Health Research Ethical Review Committee (IHRERC) (Ref.No.IHRERC/184/2022). The need for informed consent was waived by Haramaya University, College of Health and Medical Sciences Institution Health Research Ethical Review Committee (IHRERC) (Ref.No.IHRERC/184/2022). All methods were carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki’s relevant guidelines and regulations. Then, the data were collected after receiving a support letter from the administrative bodies of the health institution. This study did not expose hyponatrimic children to unnecessary risk due to reviewing their medical records. Confdentiality was maintained at all levels of the study, and the data were used only for this study purpose.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Berhanu, Y., Yusuf, T., Mohammed, A. et al. Hyponatremia and its associated factors in children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit in eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr 23, 310 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-04118-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-04118-7