Abstract

Background

Lebanon has the highest prevalence estimates among Middle Eastern countries and Arab women regarding cigarette smoking, with 43% of men and 28% of women involved in such trends. Marital disruption is a tremendous source of irritability and discomfort that may hinder a child's healthy development, creating perturbing distress and increasing disobedience that may exacerbate smoking addiction. Additionally, Lebanese adolescents are inflicted by high emotional and economic instability levels, rendering increased susceptibility to distress and propensity to engage in addictive behavior. This study aims to investigate the association between parental divorce and smoking dependence among Lebanese adolescents, along with exploring the potential mediating effect of mental health disorders of such correlation.

Methods

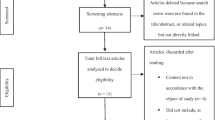

A total of 1810 adolescents (14 and 17 years) enrolled in this cross-sectional survey-based study (January-May 2019). Linear regressions were conducted to check for variables associated with cigarette and waterpipe dependence. PROCESS v3.4 model 4 was used to check for the mediating effect of mental health disorders between parental divorce and smoking dependence.

Results

Higher suicidal ideation and having divorced parents vs living together were significantly associated with more cigarette and waterpipe dependence. Higher anxiety was significantly associated with more waterpipe dependence. Insomnia and suicidal ideation played a mediating role between parental divorce and cigarette/waterpipe dependence.

Conclusion

Our results consolidate the results found in the literature about the association between parental divorce and smoking addiction and the mediating effect of mental health issues. We do not know still in the divorce itself or factors related to it are incriminated in the higher amount of smoking in those adolescents. Those results should be used to inspire parents about the deleterious effect of divorce on their children to lower their risk of smoking addiction. Further longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the complexity of such associations and to see whether the divorce experience by itself or the factors that accompany it are involved in the increased smoking addiction among adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In recent years, health care practitioners and researchers have been interested in the upsurge in psychoactive substance consumption, particularly among young adults. Remarkably, licit psychoactive substances consumption, such as cigarettes and waterpipes, is particularly widespread in adolescence and early adulthood, considered as periods of peak risk for onset and intensification of substance use behaviors that pose risks for short- and long-term health harm [1]. Undoubtedly, tobacco use is a significant public health threat, affecting more than 8 million people worldwide yearly [2], with a rapid increase in developing countries [3], mainly the Middle East region [4]. Accordingly, in 2005, the Global Youth Tobacco Survey, depicted as an all-inclusive, worldwide surveillance of smoking practice among young adults, reported that 8.6% of students smoked cigarettes while waterpipe smoking estimates vastly surpassed those of cigarettes with a 33.9% score [5]. Likewise, previous findings revealed that Lebanon had the highest prevalence estimates among Middle Eastern countries and Arab women regarding cigarette smoking [3], with 43% of men and 28% of women involved in such trends.

Moreover, Lebanon is also a significant region threatened by an escalating waterpipe smoking epidemic, with up to 35% of adolescents aged from 13 to 15 years old extensively using it [6]. Adolescence refers to a tremendously stressful transitional period [7], during which adolescents experience self-discovery to form their identity and interpersonal purposes, biological maturation, mental development processes, and determination for independence while establishing prominent social interplay with one’s environment [8,9,10]. Consequently, this array of adaptational patterns may trigger adverse emotional conditions [11], such as anxiety [12], depressive symptoms [13], and low self-esteem [14], interfering with their everyday functioning.

Previous studies revealed that adolescents who engage in the smoking practice, are highly likely to be inflicted by significant familial discordance; hence, they tend to be intensively affected by compensatory behaviors such as smoking habits to cope with their mental deficiencies and emotional needs [15,16,17]. For instance, according to Jessor et al., marital disruption and familial communication are major predictors of problematic behaviors, including alcohol consumption and smoking [18]. As such, several papers revealed that parental divorce impedes mental processes and social interconnections, rendering subsequent engagement in delinquency and deleterious patterns [19,20,21].

Moreover, previous literature highlighted increased prevalence estimates of adolescent smokers among dissolute families compared to those living with both of their parents [22, 23]. Furthermore, Wolfinger demonstrated that enduring marital disruption as a child dramatically increases the propensity to smoke in adulthood [24]. This might be due to depressive symptoms arising from familial dissolution [25] accompanying familial discordance [26]. However, several findings have established more significant irritability, depression, and emotional stressors stemming from familial discordance, which may trigger smoking and alcohol consumption [27, 28]. Thus, it has been deemed compelling to examine other speculated factors correlated to smoking practice thoroughly.

Several researchers speculated the correlation of substance dependence with mental health disorders such as anxiety, suicidal ideation, and insomnia [29,30,31]. For instance, it has been shown that smoking prevalence estimates increase with anxiety [30] as an adaptive strategy to attenuate such disturbing feelings [31]. Likewise, other findings revealed that primary smoking subsequently predicted suicidal ideation [32]. Further, Groenman et al. highlighted the fundamental role of implementing diagnostic and interventional strategies to prevent substance dependence in adulthood [33], while other findings demonstrated the efficacy of treating dependence in drastically reducing depression and anxiety symptoms [34].

Since divorce rates are steadily growing in Lebanon (an increase of 101% between 2006 and 2017) [35, 36], and since previous international studies [37, 38] have shown a relationship between divorced parents and adolescents’ addiction to smoking, assessing the background of the Lebanese situation was deemed necessary. Additionally, Lebanese adolescents are inflicted by high mental health [36, 39, 40], and emotional and economic instability levels, rendering increased susceptibility to distress and propensity to engage in addictive behavior [41]. Therefore, it is essential to identify factors incriminated in smoking dependence thoroughly, as such patterns do not hazardously occur among the population. Moreover, to our knowledge, no other study has investigated the potential mediating effect of mental health disorders in the association of parental divorce with smoking among adolescents yet. Hence, it is conceivable that the role of mental health disturbances may have been underestimated and requires further examination. Hence, this study aims to investigate the association between parental divorce and smoking dependence among Lebanese adolescents, along with exploring the potential mediating effect of mental health disorders of such correlation.

Methods

Participants

A total of 1810 adolescents out of 2000 approached (90.5%), aged between 14 and 17 years, accepted to participate in this cross-sectional study (January and May 2019). It used a proportionate random sampling of schools from all five Lebanese governorates, according to the list of the Ministry of Education and Higher Education. Out of 18 private schools approached, two declined, and 16 accepted to participate (4 in Beirut, 2 in South Lebanon, 6 in Mount Lebanon, 2 in North Lebanon, and 2 in Beqaa). All students from each school were eligible for participation. They had the right to accept or refuse to enroll in the study; with no financial rewards given in return. The methodology used in this study is similar to that in previous papers [36, 42,43,44,45,46,47].

Minimum sample size calculation

Based on the G-power software, a minimum sample size of 395 students was needed to have adequate statistical power for the multivariable analysis, according to 9 factors that should be entered in the final model.

Questionnaire

The Arabic questionnaire used was anonymous and required approximately 60 min to complete. Students filled it at school to eliminate parents influencing interventions. It consisted of two parts. The first one assessed the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, their self-reported height and weight to calculate the Body Mass Index (BMI), the number of persons in the household, and the number of rooms in the house, excluding the bathroom and the kitchen, to calculate the household crowding index (the number of persons divided by the number of rooms) [48]. It also collected the self-reported intensity, duration, and frequency of daily activity to calculate the Total Physical Activity Index by multiplying the three factors [49].

The second part included the following scales:

Lebanon Waterpipe Dependence Scale-11 (LWDS-11)

The test includes 11 items that are measured on a 4-point Likert scale to evaluate waterpipe dependence [50, 51]. Higher scores reflect higher waterpipe dependence, which was clarified as having a score of ≥ 10.

Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)

The test is based on six elements that assess cigarette dependence [52]. The scoring depends on the type of questions; yes/no questions have a score from 0 to 1, whereas multiple-choice questions are scored from 0 to 3. The higher the FTND score, the more intense the physical nicotine dependence. The scale has been previously validated in Lebanon [53].

Lebanese Anxiety Scale (LAS)

It is a 10-item tool, created for anxiety assessment among adults [54] and adolescents [55]. Items are scored based on a three- or four-point Likert scale. Higher scores reflect more anxiety.

The Adolescent Depression Rating Scale (ADRS)

This 10-item scale was developed to screen for depression among adolescents, with questions rated as yes/no. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression [56]. Two translators performed a forward and backward translation (English-Arabic-English) for the ARDS scale. Discrepancies between the two English versions were solved by consensus.

Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

This 6-item tool, validated in Lebanon [39, 57], is used to assess suicidal ideation and behavior. A score of 0 indicates the absence of suicidal ideation, while a score of 1 or more confirms the opposite [58].

Lebanese insomnia scale (LIS-18)

It is made from 18 items that cover all aspects of insomnia and its symptoms, scored on a five-point Likert scale [59]. Higher scores indicate higher insomnia levels.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed on SPSS software version 25. Cronbach’s alpha values were recorded for all the scales to assess internal consistency. Missing values constituted less than 5% of the total data and thus were not replaced. The FTND and LWDS scores were normally distributed, as verified by skewness and kurtosis values between -2 and + 2 [60]. These assumptions were consolidated by the sample size exceeding 300 [61]. Accordingly, the Student t-test was used to compare two means, whereas the Pearson test was used to correlate two continuous variables. Two linear regressions were conducted, taking the cigarette and waterpipe dependence scores as dependent variables respectively.

The mediation analysis was done using PROCESS v3.4 model 4 [62]. Pathway A determined the regression coefficient for the effect of parental divorce on the mediators (depression, anxiety, insomnia, and suicidal ideation), Pathway B examined the association between the mediators on cigarette/waterpipe dependence, independent of the psychological distress, and Pathway C’ estimated the total and direct effect of parental divorce on cigarette/waterpipe dependence. Pathway AB calculated the indirect intervention effects. Significance was assumed when the confidence interval did not include zero [62]. Independent variables entered in the linear regressions and the mediation analysis models were those that showed an effect size or a correlation coefficient ≥ │0.24│to achieve more parsimonious models [62]. Significance was set at a p < 0.05.

Results

The Cronbach’s alpha values in this study were as follows: LWDS (0.888), FTND (0.825), LAS (0.927), ARDS (0.940), C-SSRS (0.966) and LIS (0.742).

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. The mean age was 15.42 ± 1.14 years, with 53.3% of females. Additionally, 11.9% of adolescents had separated/divorced parents. Finally, 408 (22.5%) had waterpipe dependence (scores ≥ 10), whereas 459 (25.4%) had cigarette dependence (scores ≥ 0).

Bivariate analysis

Higher cigarette and waterpipe dependence was found in adolescents whose parents are divorced compared to living together and was significantly and positively associated with more insomnia, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. Furthermore, it was negatively but weakly associated with older age and a higher household crowding index (Table 2).

Multivariable analysis

The results of a first linear regression, taking the cigarette dependence scale (FTND scale) as the dependent variable, showed that higher suicidal ideation (B = 0.72) and having divorced parents vs living together (B = 1.21) were significantly associated with higher cigarette dependence (higher FTND scores) (Table 3, Model 1).

The results of a second linear regression, taking the waterpipe dependence scale (LWDS-11 scale) as the dependent variable, showed that higher suicidal ideation (B = 1.63), higher anxiety (B = 0.34) and having divorced parents vs living together (B = 2.18) were significantly associated with more waterpipe dependence (higher LWDS-11 scores) (Table 3, Model 2).

Mediation analysis

Insomnia and suicidal ideation mediated the association between parental divorce and cigarette dependence (Table 4, Model 1) and between parental divorce and waterpipe dependence (Table 4, Model 2).

Discussion

Our results showed a percentage of 22.5% for waterpipe dependence and 25.4% for cigarette dependence among enrolled students. Those numbers are higher than the ones reported by Bejjani et al. in 2012 (3.9% frequent cigarette smokers and 19% frequent waterpipe smokers [63]). Adolescents are at higher risk of substance experimentation, particularly if that substance is obtained easily and if their surroundings approve of such behavior [10]. They highly tend to search for novelty and reward dependence, while less avoiding harm [64]. Neuromaturational changes may explain the reasons for negative health behaviors seen among adolescents (substance use/abuse, mental health issues, and violence) [65]. During this complex phase, adolescents face biological and experiential changes and chart their lifestyles, which will have long-term impacts on all facets of their growth, including health [66]. These substances are often associated with partying, socializing, sharing, new experiences, and breaking the prohibitions characteristic of the adolescent period [67]. Young people do not seem to be aware of the dangers that these substances represent to their health: at their age, they display a cerebral immaturity which results in the neglect of these risks, reinforced by the fact that the damage is often observed on the means and the long-term [68].

Our findings revealed that parental divorce was significantly correlated with licit psychoactive substance consumption (cigarette and waterpipe), in line with previous literature [22, 23]. Parents neglect their children at the beginning of the divorce (while trying to resolve their issues); thus, children have a higher tendency to search for such substances to fulfill their emotional needs [69]. According to social learning theory, children's social behaviors are highly afflicted by parental warmth and interactions they witness within their families [70]. Adolescents turn to cigarettes and water pipes as a means to get the attention of their parents and as a means of “self-medication” without thinking about the long-term harmful effect of smoking [71].

Our results showed that the association between parental divorce and cigarette/waterpipe dependence is mediated by mental illness (insomnia and suicidal ideation). The stress experienced by the child during the divorce period creates an unhealthy home environment, which might consequently have a negative effect on their health [17]. Psychological distress, anger, and depression in adolescents that accompany the divorce period [22, 27, 28, 72, 73], along with a high sensation of revolution, may trigger the initiation of risky behaviors such as nicotine addiction and alcohol use [74, 75]. Previous results suggest that anxious people tend to smoke more [76]. This specifically applies to adolescents who experience conflicts within their families and turn to smoke to satisfy their psychological needs [15]. Waterpipe is becoming more popular among adolescents [6, 77] since they are more tempted to smoke water pipes because of the different flavors [78], and the lower knowledge and worse attitude about waterpipe and its harmful effects [79,80,81,82].

The current political and economic instability in Lebanon, in addition to the displacement of many Syrians following the war in their country [83], are additional causes of mental illness and destabilization among Lebanese adolescents [41, 84] and adults [57, 85,86,87]. Furthermore, Lebanese adolescents have low civic engagement and belonging to their country and feel desperate from the country’s political system following the low budget allocation, and the absence of implementation of policies and programs for youth [41].

Clinical implications

Our results have several implications. Divorcing parents need to be aware that their problems might reflect on their children's use of substances [72]. Parents should work together to make this period as easy as possible for the child and try to work with counseling services aiming at reducing parent–child conflict during parental divorce. In fact, adolescents who spent more time with their parents had less smoking [88]. Healthcare professionals should do their best to identify adolescents with mental health issues and who also have a tendency for substance use/abuse, which might prevent and treat consequent problems from the use of addictive substances [89].

Limitations

The study is cross-sectional, and thus, does not permit the inference of causality between variables. A selection bias is present since students from public schools and adolescents who do not attend schools are not represented in our sample. The symptoms were self-reported by students and were not evaluated by a healthcare professional, predisposing us to an information bias. A residual confounding bias is present as well since not all factors associated with addictions were taken into consideration in this study (parental psychiatric diseases, alcohol, smoking, and drug abuse). Adolescents were not asked when they started smoking and when their symptoms (for example insomnia) were observed (before or after the divorce).

Conclusion

Our results consolidate the results found in the literature about the association between parental divorce and smoking addiction and the mediating effect of mental health issues. We do not know still in the divorce itself or factors related to it are incriminated in the higher amount of smoking in those adolescents [88]. Those results should be used to inspire parents about the deleterious effect of divorce on their children to lower their risk of smoking addiction. Further longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the complexity of such associations and to see whether the divorce experience by itself or the factors that accompany it are involved in the increased smoking addiction among adolescents.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions from the ethics committee but are available from the corresponding author (SH) upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- LWDS:

-

Lebanon Waterpipe Dependence Scale

- FTND:

-

Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence

- LAS:

-

Lebanese Anxiety Scale

- ADRS:

-

Adolescent Depression Rating Scale

- C-SSRS:

-

Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale

- LIS:

-

Lebanese Insomnia Scale

References

Hadland SE, Harris SK. Youth marijuana use: state of the science for the practicing clinician. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26(4):420.

World Health Organization: Tobacco. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco.

Salti N, Brouwer E, Verguet S. The health, financial and distributional consequences of increases in the tobacco excise tax among smokers in Lebanon. Soc Sci Med. 2016;170:161–9.

Mzayek F, Khader Y, Eissenberg T, Al Ali R, Ward KD, Maziak W. Patterns of water-pipe and cigarette smoking initiation in schoolchildren: Irbid longitudinal smoking study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(4):448–54.

Saade G, Warren CW, Jones NR, Asma S, Mokdad A. Linking Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) data to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC): the case for Lebanon. Prev Med. 2008;47(Suppl 1):S15-19.

Bahelah R, DiFranza JR, Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Fouad FM, Taleb ZB, Jaber R, Maziak W. Waterpipe smoking patterns and symptoms of nicotine dependence: The Waterpipe Dependence in Lebanese Youth Study. Addict Behav. 2017;74:127–33.

Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24(4):417–63.

La Guardia JG. Developing who I am: A self-determination theory approach to the establishment of healthy identities. Educational Psychologist. 2009;44(2):90–104.

Casey BJ, Getz S, Galvan A. The adolescent brain. Dev Rev. 2008;28(1):62–77.

Blakemore S-J. The social brain in adolescence. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(4):267–77.

Compas BE, Hinden BR, Gerhardt CA. Adolescent development: pathways and processes of risk and resilience. Annu Rev Psychol. 1995;46:265–93.

Abe K, Suzuki T. Prevalence of some symptoms in adolescence and maturity: social phobias, anxiety symptoms, episodic illusions and idea of reference. Psychopathology. 1986;19(4):200–5.

Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, Lowry R, McManus T, Chyen D, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(4):1–131.

Thornburg HD, Jones RM. Social characteristics of early adolescents: Age versus grade. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1982;2(3):229–39.

Habibi M, Hosseini F, Darharaj M, Moghadamzadeh A, Radfar F, Ghaffari Y. Attachment Style, Perceived Loneliness, and Psychological Well-Being in Smoking and Non-Smoking University Students. J Psychol. 2018;152(4):226–36.

Nakhoul L, Obeid S, Sacre H, Haddad C, Soufia M, Hallit R, Akel M, Salameh P, Hallit S. Attachment style and addictions (alcohol, cigarette, waterpipe and internet) among Lebanese adolescents: a national study. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):33.

Jabbour N, Abi Rached V, Haddad C, Salameh P, Sacre H, Hallit R, Soufia M, Obeid S, Hallit S. Association between parental separation and addictions in adolescents: results of a National Lebanese Study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):965.

Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977.

Barrett AE, Turner RJ. Family structure and mental health: the mediating effects of socioeconomic status, family process, and social stress. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(2):156–69.

Amato PR. The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and emotional well-being of the next generation. Future Child. 2005;15(2):75–96.

Houseknecht SK, Hango DW. The impact of marital conflict and disruption on children’s health. Youth & Society. 2006;38(1):58–89.

Menning CL. Nonresident fathers’ involvement and adolescents’ smoking. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47(1):32–46.

Griesbach D, Amos A, Currie C. Adolescent smoking and family structure in Europe. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(1):41–52.

Wolfinger NH. The effects of parental divorce on adult tobacco and alcohol consumption. J Health Soc Behav. 1998;39(3):254–69.

Kirby JB. The influence of parental separation on smoking initiation in adolescents. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(1):56–71.

Amato PR, Afifi TD. Feeling caught between parents: Adult children’s relations with parents and subjective well-being. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68(1):222–35.

Sigfusdottir I-D, Farkas G, Silver E. The role of depressed mood and anger in the relationship between family conflict and delinquent behavior. J Youth Adolesc. 2004;33(6):509–22.

Jeynes WH. The effects of recent parental divorce on their children’s consumption of alcohol. J Youth Adolesc. 2001;30(3):305–19.

Chen LJ, Steptoe A, Chen YH, Ku PW, Lin CH. Physical activity, smoking, and the incidence of clinically diagnosed insomnia. Sleep Med. 2017;30:189–94.

Mondin TC, Konradt CE. Cardoso TdA, Quevedo LdA, Jansen K, Mattos LDd, Pinheiro RT, Silva RAd: Anxiety disorders in young people: a population-based study. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;35(4):347–52.

Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS. Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA. 2000;284(18):2348–51.

McGee R, Williams S, Nada-Raja S. Is cigarette smoking associated with suicidal ideation among young people? Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):619–20.

Groenman AP, Janssen TWP, Oosterlaan J. Childhood Psychiatric Disorders as Risk Factor for Subsequent Substance Abuse: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(7):556–69.

Horigian VE, Weems CF, Robbins MS, Feaster DJ, Ucha J, Miller M, Werstlein R. Reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms in youth receiving substance use treatment. Am J Addict. 2013;22(4):329–37.

The Monthly: Divorce rates in Lebanon. Available from: https://monthlymagazine.com/article-desc_4745.

Obeid S, Al Karaki G, Haddad C, Sacre H, Soufia M, Hallit R, Salameh P, Hallit S. Association between parental divorce and mental health outcomes among Lebanese adolescents: results of a national study. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):455.

Soares ALG, Gonçalves H, Matijasevich A, Sequeira M, Smith GD, Menezes A, Assunção MC, Wehrmeister FC, Fraser A, Howe LD. Parental separation and Cardiometabolic risk factors in late adolescence: a cross-cohort comparison. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(10):898–906.

Doku DT, Acacio-Claro PJ, Koivusilta L, Rimpelä A. Social determinants of adolescent smoking over three generations. Scand J Public Health. 2020;48(6):646–56.

Chahine M, Salameh P, Haddad C, Sacre H, Soufia M, Akel M, Obeid S, Hallit R, Hallit S. Suicidal ideation among Lebanese adolescents: scale validation, prevalence and correlates. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):304.

Hallit J, Salameh P, Haddad C, Sacre H, Soufia M, Akel M, Obeid S, Hallit R, Hallit S. Validation of the AUDIT scale and factors associated with alcohol use disorder in adolescents: results of a National Lebanese Study. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):205.

Youth development. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/lebanon/youth-development

Awad E, Haddad C, Sacre H, Hallit R, Soufia M, Salameh P, Obeid S, Hallit S. Correlates of bullying perpetration among Lebanese adolescents: a national study. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):204.

Dib JE, Haddad C, Sacre H, Akel M, Salameh P, Obeid S, Hallit S. Factors associated with problematic internet use among a large sample of Lebanese adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):148.

Maalouf E, Salameh P, Haddad C, Sacre H, Hallit S, Obeid S. Attachment styles and their association with aggression, hostility, and anger in Lebanese adolescents: a national study. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):104.

Malaeb D, Awad E, Haddad C, Salameh P, Sacre H, Akel M, Soufia M, Hallit R, Obeid S, Hallit S. Bullying victimization among Lebanese adolescents: The role of child abuse, Internet addiction, social phobia and depression and validation of the Illinois Bully Scale. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):520.

Sanayeh EB, Iskandar K, Fadous Khalife MC, Obeid S, Hallit S. Parental divorce and nicotine addiction in Lebanese adolescents: the mediating role of child abuse and bullying victimization. Arch Public Health. 2022;80(1):79.

Fattouh N, Haddad C, Salameh P, et al. A national study of the association of attachment styles with depression, social anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Lebanese adolescents. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2022;24(3):21m03027.

Melki I, Beydoun H, Khogali M, Tamim H, Yunis K. Household crowding index: a correlate of socioeconomic status and inter-pregnancy spacing in an urban setting. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(6):476–80.

Weary-Smith KA. Validation of the physical activity index (PAI) as a measure of total activity load and total kilocalorie expenditure during submaximal treadmill walking. PA, USA: University of Pittsburgh; 2007.

Salameh P, Waked M, Aoun Z. Waterpipe smoking: construction and validation of the Lebanon Waterpipe Dependence Scale (LWDS-11). Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(1):149–58.

Hallit S, Obeid S, Sacre H, Salameh P. Lebanese Waterpipe Dependence Scale (LWDS-11) validation in a sample of Lebanese adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1627.

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–27.

Salameh P, Khayat G, Waked M. The Lebanese Cigarette Dependence (LCD) Score: a comprehensive tool for cigarette dependence assessment. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21(2):385–93.

Hallit S, Obeid S, Haddad C, Hallit R, Akel M, Haddad G, Soufia M, Khansa W, Khoury R, Kheir N, et al. Construction of the Lebanese Anxiety Scale (LAS-10): a new scale to assess anxiety in adult patients. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2020;24(3):270–7.

Merhy G, Azzi V, Salameh P, Obeid S, Hallit S. Anxiety among Lebanese adolescents: scale validation and correlates. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):288.

Revah-Levy A, Birmaher B, Gasquet I, Falissard B. The Adolescent Depression Rating Scale (ADRS): a validation study. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:2.

Zakhour M, Haddad C, Sacre H, Fares K, Akel M, Obeid S, Salameh P, Hallit S. Suicidal ideation among Lebanese adults: scale validation and correlates. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):100.

Nilsson ME, Suryawanshi S, Gassmann-Mayer C, Dubrava S, McSorley P, Jiang K. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale Scoring and Data Analysis Guide. CSSRS Scoring Version. 2013;2:1–13.

Hallit S, Sacre H, Haddad C, Malaeb D, Al Karaki G, Kheir N, Hajj A, Hallit R, Salameh P. Development of the Lebanese insomnia scale (LIS-18): a new scale to assess insomnia in adult patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):421.

George D: SPSS for windows step by step: A simple study guide and reference, 17.0 update, 10/e: Pearson Education India; 2011.

Mishra P, Pandey CM, Singh U, Gupta A, Sahu C, Keshri A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann Card Anaesth. 2019;22(1):67–72.

Hayes AF: Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach: Guilford publications; 2017.

Bejjani N, El Bcheraoui C, Adib SM. The social context of tobacco products use among adolescents in Lebanon (MedSPAD-Lebanon). J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2012;2(1):15–22.

Awad E, Sacre H, Haddad C, Akel M, Salameh P, Hallit S, Obeid S. Association of characters and temperaments with cigarette and waterpipe dependence among a sample of Lebanese adults. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(7):8466–75.

Chambers RA, Potenza MN. Neurodevelopment, impulsivity, and adolescent gambling. J Gambl Stud. 2003;19(1):53–84.

Richter LM. Studying adolescence. Science. 2006;312(5782):1902–5.

Obradovic I. Adolescence and psychoactive substances. Soins. 2017;62(816):36–8.

Jordan CJ, Andersen SL. Sensitive periods of substance abuse: Early risk for the transition to dependence. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2017;25:29–44.

Kuntsche EN, Kuendig H. What is worse? A hierarchy of family-related risk factors predicting alcohol use in adolescence. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(1):71–86.

Ma J, Grogan-Kaylor A, Delva J. Behavior Problems Among Adolescents Exposed to Family and Community Violence in Chile. Fam Relat. 2016;65(3):502–16.

Morrell HE, Song AV, Halpern-Felsher BL. Predicting adolescent perceptions of the risks and benefits of cigarette smoking: a longitudinal investigation. Health Psychol. 2010;29(6):610–7.

Amato PR. The consequences of divorce for adults and children. J Marriage Fam. 2000;62(4):1269–87.

Thoits PA. Stress, coping, and social support processes: where are we? What next? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;Spec No:53-79. PMID: 7560850.

Savolainen I, Kaakinen M, Sirola A, Oksanen A. Addictive behaviors and psychological distress among adolescents and emerging adults: A mediating role of peer group identification. Addict Behav Rep. 2018;7:75–81.

Primack BA, Land SR, Fan J, Kim KH, Rosen D. Associations of mental health problems with waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking among college students. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(3):211–9.

Wise MH, Weierbach F, Cao Y, Phillips K. Tobacco Use and Attachment Style in Appalachia. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2017;38(7):562–9.

World Health Organization. Advisory note: waterpipe tobacco smoking. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_interaction/tobreg/Waterpipe%20recommendation_Final.pdf.

Wagener TL, Leavens ELS, Mehta T, Hale J, Shihadeh A, Eissenberg T, Halquist M, Brinkman MC, Johnson AL, Floyd EL, Ding K, El Hage R, Salman R. Impact of flavors and humectants on waterpipe tobacco smoking topography, subjective effects, toxicant exposure and intentions for continued use. Tob Control. 2020 May 13:tobaccocontrol-2019-055509. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055509.

Hallit S, Haddad C, Bou Malhab S, Khabbaz LR, Salameh P. Construction and validation of the water pipe harm perception scale (WHPS-6) among the Lebanese population. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27(3):3440–8.

Akiki Z, Saadeh D, Haddad C, Sacre H, Hallit S, Salameh P. Knowledge and attitudes toward cigarette and narghile smoking among previous smokers in Lebanon. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27(12):14100–7.

Farah R, Haddad C, Sacre H, Hallit S, Salameh P. Knowledge and attitude toward waterpipe smoking: scale validation and correlates in the Lebanese adult population. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27(25):31250–8.

Haddad C, Lahoud N, Akel M, Sacre H, Hajj A, Hallit S, Salameh P. Knowledge, attitudes, harm perception, and practice related to waterpipe smoking in Lebanon. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27(15):17854–63.

Obeid S, Haddad C, Salame W, Kheir N, Hallit S. Xenophobic attitudes, behaviors and coping strategies among Lebanese people toward immigrants and refugees. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;55(4):710–7.

Sfeir E, Geara C, Hallit S, Obeid S. Alexithymia, aggressive behavior and depression among Lebanese adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:32.

Obeid S, Akel M, Haddad C, Fares K, Sacre H, Salameh P, Hallit S. Factors associated with alexithymia among the Lebanese population: results of a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2019;7(1):80.

Obeid S, Lahoud N, Haddad C, Sacre H, Akel M, Fares K, Salameh P, Hallit S. Factors associated with depression among the Lebanese population: Results of a cross-sectional study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2020;56(4):956–67.

Obeid S, Lahoud N, Haddad C, Sacre H, Fares K, Akel M, Salameh P, Hallit S. Factors associated with anxiety among the Lebanese population: the role of alexithymia, self-esteem, alcohol use disorders, emotional intelligence and stress and burnout. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2020;24(2):151–62.

Kristjansson AL, Sigfusdottir ID, Allegrante JP, Helgason AR. Parental divorce and adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use: assessing the importance of family conflict. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(3):537–42.

Horta RL, Horta BL, Pinheiro RT, Morales B, Strey MN. Tobacco, alcohol, and drug use by teenagers in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil: a gender approach. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(4):775–83.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants and those who helped in this project mainly Dr Melissa Chahine, Dr Jennifer Hallit and Dr Jad Chidiac.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SO and SH designed the study; VA drafted the manuscript; SH carried out the analysis and interpreted the results; KI assisted in drafting and reviewing the manuscript; all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The Psychiatric Hospital of the Cross Ethics and Research Committee approved this study protocol (HPC-012–2019). Written informed consent was obtained from the students’ parents before starting data collection. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (declaration of Helsinki).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Azzi, V., Iskandar, K., Obeid, S. et al. Parental divorce and smoking dependence in Lebanese adolescents: the mediating effect of mental health problems. BMC Pediatr 22, 471 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03523-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03523-8