Abstract

Background

The prevalence in the Lebanese general population of cigarette and waterpipe smoking, alcohol drinking and internet use seems to be increasing lately. So far, no study was done relating the above to attachment styles in Lebanese adolescents. Consequently, the objective of our study was to assess the relationship between attachment styles (secure, preoccupied, fearful, and dismissing) and addictions (cigarettes, water pipes, alcohol, and internet) among this population.

Methods

It is a cross-sectional study that took place between January and May 2019. Two thousand questionnaires were distributed out of which 1810 (90.5%) were completed and collected back. A proportionate random sample of schools from all Lebanese Mohafazat was used as recruitment method.

Results

A secure attachment style was significantly associated with lower addiction to alcohol, cigarette, and waterpipe, whereas insecure attachment styles (preoccupied, dismissing and fearful) were significantly associated with higher addiction to cigarette, waterpipe, alcohol, and internet.

Conclusion

Lebanese adolescents with insecure attachment had higher rates of addiction to cigarette, waterpipe, alcohol, and internet. They should be closely monitored in order to reduce the risk of future substance use disorder and/or behavioral addiction development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Originally proposed [1], then developed by John Bowlby [2] and Mary Ainsworth [3], the attachment theory explains the effect of interpersonal relationships on normal and abnormal psychological functioning. According to Bowlby, the quality of close relationships between people, from early childhood, interferes in the elaboration of mental representations of oneself and others. These representations constitute the roots for social experiences and environmental understandings. This being said those representations might be the source of vulnerability in the case of personal history of insecure relationships, or on the contrary source of resilience in the case of secured ones [4]. Four types of attachment styles were identified: secure, anxious or preoccupied, dismissive, and fearful. Securely attached people are optimistic about themselves and others [5]; their caregivers were emotionally stable and provided them with quality time during childhood, thereby regulating their positive and negative emotions [6]. Preoccupied people are optimistic about others but pessimistic about themselves, hence worried about relationships [5]. Dismissive people are optimistic about themselves but pessimistic about others, therefore, do not value relations [5]. Fearful people are pessimistic about themselves and others; they think they are unlovable and untrustworthy, and others will reject them [5].

According to Attachment Theory, humans are biologically prone to create strong bonds with other humans from whom they receive emotional support and protection [1]. The type of attachment that will an infant develop towards its primary caregiver will have future implications on his social and emotional functioning at an older age. These ties will play vital roles throughout the life of individuals [7]. As children grow, they develop new attachment relationships with friends and romantic partners [8], and most adults report using both parents and their romantic partners as attachment figures [9]. In other words, the formation of attachment is a process of development that persists well beyond infancy and childhood [10]. During adolescence, representations of attachment relationships can be continually changed as individuals develop new intimate relationships [11]. This process of change is not only the product of the adolescent’s autonomy and increased physical abilities, but also of cognitive development that marks the transition to formal operations, which greatly increases the individual’s ability to think about his motivations and interpersonal relationships [12]. Alongside the increase in the adolescent’s abstract thinking capacity, there are many environmental issues, including the transition to university, the development of more intimate relationships, concerns about self-image and puberty, possible family problems, and the development of sexuality [13]. This association of increased abilities and increased environmental constraints during adolescence seems to create ideal conditions for the development of a wider range of intimate relationships, and vulnerability to the development of dysfunctional behavior, such as addiction [1, 14] that is defined by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) as “a primary chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry” [15]. Many believe that addictions are a coping mechanism and that the attachment style can play a key role in the development of addictions [16], such as those related to smoking, alcohol, and internet.

Previous findings suggest that smokers were more likely to be of the anxious type [17]. Indeed, young adults who tend to smoke have more conflicts within their families and are, therefore, influenced by external objects, such as cigarettes to overcome their psychological needs [18], but to our knowledge, no studies have shown an association between waterpipe addiction in adolescence and attachment styles.

As for alcohol use disorder, previous studies revealed that subjects addicted to alcohol and other psychoactive substances are very likely to have insecure and avoidance attachment styles [19, 20], in addition to higher anxiety-trait, alexithymia, and schizoid traits [19, 21].

Moreover, a correlation was found between insecure attachment style and internet addiction [22]. In fact, the secure type was shown to be a protective factor against internet addiction since people with this attachment style have a high self-esteem in face-to-face relationships [23]. In contrast, the anxious type was associated with higher social networking addiction because people of this type make huge efforts to be accepted by others. They also fear face-to-face interactions and have, through social networking, the advantage of choosing the time for interacting with other people and the way they present themselves to others [23, 24]. The avoidant type is also correlated with higher social networking addiction since these people satisfy their social needs through online platforms while keeping a safe distance [23].

The incidence of cigarette smoking is increasing globally, with a higher incidence in developing countries [25], where Lebanon ranks first in terms of smoking prevalence in the Middle-East and among Arab women [25]. Its prevalence is also rising among adolescents (3.9% frequent smokers in 2012), especially in the presence of a family member or friend who smokes [26]. Similarly, the prevalence of waterpipe use is high in Lebanon, with up to 35% of the 13 to 15 years old category having already used it [27]. Actually, waterpipes are more appealing to adolescents due to the different flavors and look, and due to the false idea of waterpipe smoking being a non-harmful method [28], its use in adolescent population is popular [29, 30]. Its popularity among adolescents might be also due to its social acceptance [31]. This also leads to an increase in its prevalence (19% of Lebanese adolescents were frequent waterpipe users in 2012) [26]. Moreover, the lack in the application of the laws protecting minors from drinking alcohol makes it easier for them to buy it with no respect to age restrictions. This, combined with alcohol cheap prices in Lebanon play a role in the increase of alcohol consumption in this category [32]. Alcohol use among adolescence is due to curiosity, power feeling, media influence and to cope with stress [33, 34]. This might explain the increased alcohol addiction in adolescents (an increase in Lebanese adolescent lifetime drunkenness between 2005 and 2011 by 48%) [35]. As for Internet addiction, studies revealed that the global prevalence is 1.6 to 18% [36] and varies with sex, age, and ethnicity [37]. In Lebanon, it is around 40–42% among adolescents [38, 39]. High incidence is explained by the fact that social media is used to enhance friendly relationships [40] whereas gaming activities, interactive platforms, hook adolescents to the internet leading to an increased risk of addiction by increasing internet usage time [41].

In addition to all these factors, Lebanese adolescents [42] and adults [43] have to face many other stressors leading them to high levels of exclusion and destabilization, such as the Syrian crisis and the resulting immigration, internal instability, and the persistent economic inequalities. Moreover, Lebanese adolescents have a low level of participation and civic engagement and feel powerless in the political system due to lack of representation, low budget allocation, and weak implementation of policies and programs for youth (Unicef Lebanon). All these factors can increase the risk of addiction among adolescents, with previous studies showing that adolescents with anxious attachment may have alcohol problems [44]. In such settings, and since the prevalence in the Lebanese general population of cigarette and waterpipe smoking, alcohol drinking and internet use seems to be increasing lately [45, 46], and in the absence of studies on their association with attachment styles, it decision to conduct such a research among Lebanese adolescents was taken. Consequently, the objective of our study was to assess the relationship between attachment styles (secure, preoccupied, fearful, and dismissing) and addictions (cigarettes, water pipes, alcohol, and internet) among Lebanese adolescents.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted between January and May 2019. A proportionate random sample of schools from all Lebanese Mohafazat (Beirut, Mount Lebanon, North, South and Bekaa) was used as recruitment method. The list of schools was obtained from the Ministry of Education and Higher Education in Lebanon. From each mohafaza, a proportionate number to the total number of schools was selected; in case of school refusal to participate, replacement was not done. Out of the of the 18 private schools contacted, 2 refused to participate, and the 16 that accepted were located as follows: 4 in Beirut, 2 in South Lebanon, 6 in the Mount Lebanon, 2 in North Lebanon, and 2 in Bekaa. All students, aged between 14 and 17 years old, from each school were eligible to participate. Students who refused to fill the questionnaire were excluded. The methodology used has been previously described [39, 44, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

Minimal sample size

Since there are no similar studies in Lebanon, we postulated that an insecure attachment style would increase waterpipe dependence moderately (effect size r = 0.3). The G-power software estimated a minimal sample of 134 participants (power of 95%). The total sample at the end of the data collection consisted of 1810 (90.5%) questionnaires collected back out of 2000 distributed.

Questionnaire

A study-independent personnel was responsible for the distribution of the questionnaire. It was in Arabic, the native language of Lebanon, and required approximately 30 min to complete. Students were asked to fill out the questionnaire during classes to avoid parental influence in answering questions. The anonymity of the participants was guaranteed during the data collection process.

The sociodemographic details of the participants were addressed in the first part of the questionnaire (i.e. age, gender, smoking status). Participants self-reported their heights and weights based on which the Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2) was calculated. The household crowding index was calculated by dividing the number of persons living in the house by the number of rooms in the house, excluding the bathroom and the kitchen [73].

The second part of the questionnaire included the following scales:

Relationship questionnaire (RQ)

This questionnaire consists of four short paragraphs, each describing one of the four adult attachment styles. Style A relates to the secure attachment, Style B to the preoccupied attachment, Style C to the fearful attachment, and Style D to the dismissing attachment [74]. Each paragraph is rated on a 7-points Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) (αCronbach in this study = 0.970).

Internet addiction test (IAT)

This 20-item tool is rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 = does not apply/never to 5 = always applies [75]. The total score varied between 20 and 100, with higher scores defining higher internet addiction (αCronbach in this study = 0.925). This scale has previously been validated among Lebanese adolescents [76].

The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT)

This self-reported screening tool consists of 10 items and assesses alcohol use, drinking patterns, and alcohol-related issues [77]. The AUDIT scale was shown to have an acceptable sensitivity for the identification of alcohol problems in adolescents aged between 14 and 18 years old [78]. A score equal to or greater than 8 indicates the presence of an alcohol use disorder (αCronbach in this study = 0.960).

Lebanon Waterpipe dependence Scale-11 (LWDS-11)

This test is used to assess waterpipe dependence [79]. It includes 11 items measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3; higher scores reflect higher waterpipe dependence (αCronbach in this study = 0.888).

Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (FTND)

This 6-item tool is used to assess the intensity of physical addiction to nicotine related to cigarette smoking. The higher the total score, the more intense the patient’s physical dependence on nicotine [80]. This scale can be used to asses cigarette addiction in adolescents [81] (αCronbach in this study = 0.825).

Translation procedure

The translation from English to Arabic was carried out by a single bilingual translator. A backward translation was then performed by a native English-speaking translator, fluent in Arabic and unfamiliar with the concepts of the scales. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus between translators and researchers.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software version 23. Cronbach’s alpha values were recorded for reliability analysis for all the scales. Missing data was not replaced since it formed less than 10% of the total data. Attachment styles measures were then dichotomized according to the mean. For bivariate analysis, the Student’s test was used to compare means between two groups, and correlation coefficients were used to assess the association between continuous variables. In all cases, a p-value lower than 0.05 was considered significant. A multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was carried out to compare multiple measures (each addiction scale was taken as a dependent variable) between the dichotomized attachment styles categories, taking into account potential confounding variables: age, gender, house crowding index and BMI. A p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 15.42 ± 1.14 years, with 53.3% females. The means and standard deviations for the scales were as follows: AUDIT (6.46 ± 8.44), IAT (39.42 ± 18.08), FTND (1.53 ± 2.83) and LWDS (4.73 ± 8.68). Furthermore, the results showed that 43.45% of the participants had a secure attachment style [95% CI 0.408–0.461], 44.18% a preoccupied style [95% CI 0.442–0.415], 49.01% a fearful style [95% CI 0.464–0.517] and 45.50% a dismissing style [95% CI 0.429–0.481].

Bivariate analysis

No significant difference was found between genders in terms of alcohol use disorder, cigarette, and waterpipe dependence (Table 2). Higher internet addiction, cigarette and waterpipe dependence, fearful style, and dismissing style were significantly associated with higher alcohol use disorders, whereas higher secure and preoccupied styles were significantly associated with lower alcohol use disorders. Higher cigarette and waterpipe dependence, higher age, preoccupied and fearful styles were significantly associated with higher internet addiction. Higher waterpipe dependence, preoccupied, fearful, and dismissing styles were significantly associated with higher cigarette dependence, whereas higher age, higher house crowding index, and higher secure style were significantly associated with lower cigarette dependence. Higher body mass index, preoccupied, fearful, and dismissing styles were significantly associated with higher waterpipe dependence, whereas higher age, house crowding index, and secure style were significantly associated with lower waterpipe dependence (Table 3).

Addiction scores means according to attachment styles

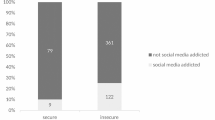

The adjusted means for the addiction scores according to each attachment style are summarized in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4. In all types of addiction, a secure attachment style is associated with lower addiction, while unsecured attachment styles were significantly associated with higher addiction.

Multivariate analysis

The MANCOVA analysis was performed taking the scales as the dependent variable and the attachment styles as independent variables, after adjusting for the covariates (age, gender, house crowding index and BMI).

A secure relationship style was significantly associated with lower AUDIT scores (B = -3.35), lower cigarette (B = -1.57) and waterpipe (B = -2.73) dependence. A fearful relationship style was significantly associated with higher AUDIT scores (B = 1.83), internet addiction (B = 4.46) and cigarette dependence (B = 0.58). A dismissing relationship style was significantly associated with higher AUDIT scores (B = 1.79), internet addiction (B = 2.64), cigarette (B = 1.77) and waterpipe (B = 4.23) dependence. Finally, a preoccupied relationship style was significantly associated with higher internet addiction (B = 8.84), cigarette (B = 1.43) and waterpipe (B = 3.95) dependence (Table 4).

Discussion

This is the first study of its kind in Lebanon to address the association between the attachment styles and addictions in adolescents. A secure attachment style was significantly associated with lower addiction to alcohol, cigarette, and waterpipe, whereas insecure attachment styles (preoccupied, dismissing and fearful) were significantly associated with higher addiction to cigarette, waterpipe, alcohol, and internet.

A secure attachment style, increased age, and higher house crowding index were associated with lower cigarette smoking addiction in adolescents, as opposed to insecure attachment styles (preoccupied, dismissing, and fearful) and female gender, in line with previous research [18, 82]. Indeed, people with insecure attachment styles have low self-esteem and more anxiety, which increase substance abuse, such as smoking, especially in cases of emotional distress [83]. Further, people with insecure attachment (high avoidance/anxiety) have a lower capability to self-regulate during stressful times/situations and consequently look for external methods to relieve their stress, such as tobacco use; hence, tobacco use can be considered as a coping mechanism for stress in those persons [84]. The negative association between increased house crowding index and smoking can be hypothesized by the fact that a crowded house does not give to adolescents freedom or the time to smoke alone, especially if their roommate is annoyed by passive smoking.

Waterpipe addiction was positively associated with all insecure attachment styles and negatively associated with increased age. This could be due to the same reasons related to cigarette smoking. According to studies, a 45-min waterpipe smoking is equivalent to approximately 40 cigarettes [85]. These high nicotine levels in waterpipe are believed to relieve anxiety and mitigate psychological problems [86]. Another factor that has significantly contributed to the increased use of the waterpipe is the perception of its “positive” attributes, such as socializing, relaxing, and the good taste/smell of the smoke; these attributes seem to encourage and maintain waterpipe use, thereby reducing anxiety [87]. However, as adolescents grow older, they learn more about the side effects of waterpipe and cigarette smoking, which can explain the negative association between aging and both smoking addictions [88].

Our results also show that the secure attachment style was negatively associated with alcohol addiction, contrary to insecure attachment styles, consistent with previous findings on adults [44]. This is probably due to the fact that people with insecure attachment styles have problems with anxiety and relationship stability, which increases the risk of any substance abuse, including alcohol [19]. Alcohol is a substrate of the GABAergic receptors that decreases anxiety and controls emotions; this means that people with an insecure attachment style will feel more relieved by drinking alcohol, which can lead to addiction over time [19]. Female gender was also associated with alcohol addiction. In fact, alcohol is absorbed faster and metabolized slower in women [89], leading to higher blood alcohol concentrations in women for a longer time with the same amount of ingested alcohol, thereby increasing the risk of addiction.

As for internet addiction, it was positively related with insecure attachment styles (preoccupied and dismissing) in adolescents, consistent with previous studies [16]. People with an insecure style have problems with self and/or others’ image, thus hindering direct relationships [5]. Consequently, they prefer indirect relationships, using social media, to face-to-face relationships (e.g. Facebook); this will increase the time spent on social media, resulting in an increased risk of internet addiction [23, 24]. On another hand, people with a secure attachment style have high self-esteem and do not have any difficulty sharing their feelings with others, making them able to manage time spent on social media without becoming addict [7].

Clinical implications

The relationship between insecure attachment styles and addictions require specific treatment considerations. Thus, it appears reasonable to take therapeutic actions to support persons reporting real-life shortfalls; this can be achieved either by a good patient-communication relationship, which can be considered as a “substitute attachment figure” or by a group therapy that can also provide corrective relationship experiences. In addition, prevention programs are warranted, and healthcare providers could explore tools to build a more secure attachment in children to possibly decrease the likelihood of future addictions (tobacco, waterpipe, alcohol and internet addiction) initiation.

Limitations

This study has few limitations. Its cross-sectional nature does not allow inferring causality due to temporality issues. The Relationship Questionnaire is a very reductive form of measurement for adult attachment and close relationships. It was not validated among adolescents in Lebanon, which may lead to a non-differential information bias, underestimating the relationship between attachment style and addictive behaviors. All scales used, except the IAT, have not been validated among Lebanese adolescents, which might have led to a non-differential information bias; this might explain the negative correlation between age with smoking (cigarettes and waterpipe). This finding, in itself, could be pointing to the issue of addiction needing to be measured differently during adolescence due to the tendency for adolescents to experiment this kind of addiction during this period of development. Information bias might be present because of trouble understanding a question. The study did not include adolescents not attending schools, which hinders extrapolation to out-of-school adolescents where addiction problems might be expected to be more common. Finally, a selection bias might be present because of the selection process of schools since public schools were not included. However, we believe that our results are generalizable to the whole adolescents’ population in Lebanon.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Lebanese adolescents with insecure attachment had higher rates of addiction to cigarette, waterpipe, alcohol, and internet. They should be continuously followed-up to avoid developing any addiction that could potentially harm them. Future studies that include out-of-school adolescents are warranted to confirm our findings.

Availability of data and materials

Data can be made available under reasonable request form the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ASAM:

-

American Society of Addiction Medicine

- RQ:

-

Relationship questionnaire

- IAT:

-

Internet Addiction Test

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- LWDS:

-

Lebanon waterpipe dependence scale

- FTND:

-

Fagerström test for nicotine dependence

References

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. New York: Basic Books; 1969.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Loss, sadness and depression (Vol. 3). New York: Basic Books; 1980.

Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1978.

Ainsworth MS, Bowlby J. An ethological approach to personality development. Am Psychol. 1991;46(4):333.

Van Buren A, Cooley EL. Attachment styles, view of self and negative affect; 2002.

Sable P. What is adult attachment? Clin Soc Work J. 2008;36(1):21–30.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: separation: anxiety and anger, vol. 2Vintage; 1980.

Nickerson AB, Nagle RJ. Parent and peer attachment in late childhood and early adolescence. J Early Adolesc. 2005;25(2):223–49.

Doherty NA, Feeney JA. The composition of attachment networks throughout the adult years. Pers Relat. 2004;11(4):469–88.

Allen JP, Porter M, McFarland C, McElhaney KB, Marsh P. The relation of attachment security to adolescents' paternal and peer relationships, depression, and externalizing behavior. Child Dev. 2007;78(4):1222–39.

Simpson JA, Collins WA, Tran S, Haydon KC. Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in romantic relationships: a developmental perspective. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(2):355–67.

Kobak R, Cole H. Attachment and meta-monitoring: implications for adolescent autonomy and psychopathology. Disord Dysfunctions Self. 1994;5:267.

Shaw SK, Dallos R. Attachment and adolescent depression: the impact of early attachment experiences. Attach Hum Dev. 2005;7(4):409–24.

Monasterio E. Vulnerabilities of adolescence and Young adulthood. In: Medical Management of Vulnerable and Underserved Patients: principles, practice, populations; 2016. p. 226.

Smith DE. The process addictions and the new ASAM definition of addiction. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2012;44(1):1–4.

Estevez A, Jauregui P, Lopez-Gonzalez H. Attachment and behavioral addictions in adolescents: the mediating and moderating role of coping strategies. Scand J Psychol. 2019;60(4):348–60.

Wise MH, Weierbach F, Cao Y, Phillips K. Tobacco use and attachment style in Appalachia. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2017;38(7):562–9.

Habibi M, Hosseini F, Darharaj M, Moghadamzadeh A, Radfar F, Ghaffari Y. Attachment style, perceived loneliness, and psychological well-being in smoking and non-smoking university students. J Psychol. 2018;152(4):226–36.

Wedekind D, Bandelow B, Heitmann S, Havemann-Reinecke U, Engel KR, Huether G. Attachment style, anxiety coping, and personality-styles in withdrawn alcohol addicted inpatients. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2013;8(1):1.

Juen F, Arnold L, Meissner D, Nolte T, Buchheim A. Attachment disorganization in different clinical groups: what underpins unresolved attachment? Psihologija. 2013;46(2):127–41.

Thorberg FA, Young RM, Sullivan KA, Lyvers M, Connor JP, Feeney GF. Alexithymia, craving and attachment in a heavy drinking population. Addict Behav. 2011;36(4):427–30.

Lin M-P, Ko H-C, Wu JY-W. Prevalence and psychosocial risk factors associated with internet addiction in a nationally representative sample of college students in Taiwan. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(12):741–6.

Monacis L, De Palo V, Griffiths MD, Sinatra M. Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen social media addiction scale. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(2):178–86.

Marino C, Marci T, Ferrante L, et al. Attachment and problematic Facebook use in adolescents: the mediating role of metacognitions. J Behav Addict. 2019;8(1):63–78.

Salti N, Brouwer E, Verguet S. The health, financial and distributional consequences of increases in the tobacco excise tax among smokers in Lebanon. Soc Sci Med. 2016;170:161–9.

Bejjani N, El Bcheraoui C, Adib SM. The social context of tobacco products use among adolescents in Lebanon (MedSPAD-Lebanon). J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2012;2(1):15–22.

Bahelah R, DiFranza JR, Ward KD, et al. Waterpipe smoking patterns and symptoms of nicotine dependence: the Waterpipe dependence in Lebanese youth study. Addict Behav. 2017;74:127–33.

Eissenberg T, Ward KD, Smith-Simone S, Maziak W. Waterpipe tobacco smoking on a U.S. college campus: prevalence and correlates. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(5):526–9.

Hallit S, Haddad C, Bou Malhab S, Khabbaz LR, Salameh P. Construction and validation of the water pipe harm perception scale (WHPS-6) among the Lebanese population. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27(3):3440–8.

World Health Organization. Advisory note: water pipe tobacco smokingAvailable from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_interaction/tobreg/Waterpipe%20recommendation_Final.pdf; 2009.

Dar-Odeh NS, Abu-Hammad OA. The changing trends in tobacco smoking for young Arab women; narghile, an old habit with a liberal attitude. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8(1):24.

Yassin N, Afifi R, Singh N, Saad R, Ghandour L. "there is zero regulation on the selling of alcohol": the voice of the youth on the context and determinants of alcohol drinking in Lebanon. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(5):733–44.

Coleman LM, Cater SM. A qualitative study of the relationship between alcohol consumption and risky sex in adolescents. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34(6):649–61.

Massad SG, Shaheen M, Karam R, et al. Substance use among Palestinian youth in the West Bank, Palestine: a qualitative investigation. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):800.

Ghandour L, Afifi R, Fares S, El Salibi N, Rady A. Time trends and policy gaps: the case of alcohol misuse among adolescents in Lebanon. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(14):1826–39.

Shaw M, Black DW. Internet addiction. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(5):353–65.

Pujazon-Zazik M, Park MJ. To tweet, or not to tweet: gender differences and potential positive and negative health outcomes of adolescents’ social internet use. Am J Mens Health. 2010;4(1):77–85.

Hawi NS. Internet addiction among adolescents in Lebanon. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28(3):1044–53.

Obeid S, Saade S, Haddad C, et al. Internet addiction among Lebanese adolescents: the role of self-esteem, anger, depression, anxiety, social anxiety and fear, impulsivity, and aggression-a cross-sectional study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207(10):838–46.

Young KS. Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1(3):237–44.

Kheyrkhah F, Ghabeli JA, Gouran A. Internet addiction, prevalence and epidemiological features in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran; 2010.

Unicef Lebanon. Youth development. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/lebanon/youth-development. Accessed 2 Dec 2019.

Obeid S, Haddad C, Salame W, Kheir N, Hallit S. Xenophobic attitudes, behaviors and coping strategies among Lebanese people toward immigrants and refugees. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;55(4):710–7.

Obeid S, Haddad C, Akel M, Fares K, Salameh P, Hallit S. Factors associated with the adults' attachment styles in Lebanon: the role of alexithymia, depression, anxiety, stress, burnout, and emotional intelligence. In: Perspectives in psychiatric care; 2019.

Alomari MA, Al-Sheyab NA. Impact of waterpipe smoking on blood pressure and heart rate among adolescents: the Irbid-TRY. J Subst Abuse. 2018;23(3):280–5.

Dalbudak E, Evren C, Aldemir S, Evren B. The severity of internet addiction risk and its relationship with the severity of borderline personality features, childhood traumas, dissociative experiences, depression and anxiety symptoms among Turkish university students. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):577–82.

Haddad C, Hallit R, Akel M, et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the ORTO-15 questionnaire in a sample of the Lebanese population. In: Eating and weight disorders-studies on anorexia, bulimia and obesity; 2019. p. 1–10.

Haddad C, Obeid S, Akel M, et al. Correlates of orthorexia nervosa among a representative sample of the Lebanese population. Eating Weight Disord-Stud Anorexia, Bulimia Obes. 2019;24(3):481–93.

Haddad C, Zakhour M, Akel M, et al. Factors associated with body dissatisfaction among the Lebanese population. In: Eating and weight disorders-studies on anorexia, bulimia and obesity; 2019. p. 1–13.

Khansa W, Haddad C, Hallit R, et al. Interaction between anxiety and depression on suicidal ideation, quality of life, and work productivity impairment: results from a representative sample of the Lebanese population. In: Perspectives in psychiatric care; 2019.

Lahoud N, Zakhour M, Haddad C, et al. Burnout and its relationships with alexithymia, stress, self-esteem, depression, alcohol use disorders, and emotional intelligence: results from a Lebanese cross-sectional study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207(8):642–50.

Obeid S, Fares K, Haddad C, et al. Construction and validation of the Lebanese fear of relationship commitment scale among a representative sample of the Lebanese population. In: Perspectives in psychiatric care; 2019.

Obeid S, Sacre H, Haddad C, et al. Factors associated with fear of intimacy among a representative sample of the Lebanese population: the role of depression, social phobia, self-esteem, intimate partner violence, attachment, and maladaptive schemas. In: Perspectives in psychiatric care; 2019.

Obeid S, Akel M, Haddad C, et al. Factors associated with alexithymia among the Lebanese population: results of a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2019;7(1):80.

Saade S, Hallit S, Haddad C, et al. Factors associated with restrained eating and validation of the Arabic version of the restrained eating scale among an adult representative sample of the Lebanese population: a cross-sectional study. J Eat Disord. 2019;7(1):24.

Haddad C, Zakhour M, Akel M, et al. Factors associated with body dissatisfaction among the Lebanese population. In: Eat weight Disord; 2019.

Zeidan RK, Haddad C, Hallit R, et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the binge eating scale and correlates of binge eating disorder among a sample of the Lebanese population. J Eat Disord. 2019;7(1):40.

Zakhour M, Haddad C, Salameh P, et al. Impact of the interaction between alexithymia and the adult attachment styles in participants with alcohol use disorder. Alcohol. 2019;83:1–8.

Sfeir E, Haddad C, Salameh P, et al. Binge eating, orthorexia nervosa, restrained eating, and quality of life: a population study in Lebanon. In: Eating and weight disorders-studies on anorexia, bulimia and obesity; 2019. p. 1–14.

Obeid S, Haddad C, Zakhour M, et al. Correlates of self-esteem among the Lebanese population: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatr Danub. 2019;31(4):429–39.

Fares K, Hallit S, Haddad C, Akel M, Khachan T, Obeid S. Relationship between cosmetics use, self-esteem, and self-perceived attractiveness among Lebanese women. J Cosmet Sci. 2019;70(1):47–56.

Hallit S, Sacre H, Haddad C, et al. Development of the Lebanese insomnia scale (LIS-18): a new scale to assess insomnia in adult patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):421.

Obeid S, Haddad C, Akel M, Fares K, Salameh P, Hallit S. Factors associated with the adults' attachment styles in Lebanon: the role of alexithymia, depression, anxiety, stress, burnout, and emotional intelligence. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;55:607–17.

Hallit S, Hajj A, Sacre H, et al. Impact of sleep disorders and other factors on the quality of life in general population: a cross-sectional study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207(5):333–9.

Rahme C, Haddad C, Akel M, et al. Factors associated with violence against women in a representative sample of the Lebanese population: results of a cross-sectional study. Arch Womens Ment Health; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01022-2.

Rahme C, Haddad C, Akel M, et al. Does Stockholm syndrome exist in Lebanon? Results of a cross-sectional study considering the factors associated with violence against women in a Lebanese representative sample. J Interpers Violence. 2020:886260519897337.

Haddad C, Darwich MJ, Obeid S, et al. Factors associated with anxiety disorders among patients with substance use disorders in Lebanon: results of a cross-sectional study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12462.

Obeid S, Sacre H, Haddad C, et al. Factors associated with fear of intimacy among a representative sample of the Lebanese population: the role of depression, social phobia, self-esteem, intimate partner violence, attachment, and maladaptive schemas. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12438.

Obeid S, Fares K, Haddad C, et al. Construction and validation of the Lebanese fear of relationship commitment scale among a representative sample of the Lebanese population. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12424.

Haddad C, Zakhour M, Akel M, et al. Factors associated with body dissatisfaction among the Lebanese population. Eating Weight Disord: EWD. 2019;24(3):507–19.

Obeid S, Lahoud N, Haddad C, et al. Factors associated with anxiety among the Lebanese population: the role of alexithymia, self-esteem, alcohol use disorders, emotional intelligence and stress and burnout. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2020:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2020.1723641.

Hallit S, Obeid S, Haddad C, et al. Construction of the Lebanese anxiety scale (LAS-10): a new scale to assess anxiety in adult patients. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2020:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2020.1744662.

Melki I, Beydoun H, Khogali M, Tamim H, Yunis K. Household crowding index: a correlate of socioeconomic status and inter-pregnancy spacing in an urban setting. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(6):476–80.

Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(2):226.

Young KS. Psychology of computer use: XL. Addictive use of the internet: a case that breaks the stereotype. Psychol Rep. 1996;79(3):899–902.

Samaha AA, Fawaz M, El Yahfoufi N, et al. Assessing the psychometric properties of the internet addiction test (IAT) among Lebanese college students. Front Public Health. 2018;6:365.

Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56(4):423–32.

Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Chang G. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: a comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(1):67–73.

Salameh P, Waked M, Aoun Z. Waterpipe smoking: construction and validation of the Lebanon Waterpipe dependence scale (LWDS-11). Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(1):149–58.

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–27.

Carpenter MJ, Baker NL, Gray KM, Upadhyaya HP. Assessment of nicotine dependence among adolescent and young adult smokers: a comparison of measures. Addict Behav. 2010;35(11):977–82.

Narain R, Sardana S, Gupta S, Sehgal A. Age at initiation & prevalence of tobacco use among school children in Noida, India: a cross-sectional questionnaire based survey. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133(3):300.

Kassel JD, Wardle M, Roberts JE. Adult attachment security and college student substance use. Addict Behav. 2007;32(6):1164–76.

Wise MH. Tobacco use and attachment styles. Available from: https://dc.etsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1300&context=honors. Accessed 2 Dec 2019.

Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):518–23.

Picciotto MR, Brunzell DH, Caldarone BJ. Effect of nicotine and nicotinic receptors on anxiety and depression. Neuroreport. 2002;13(9):1097–106.

Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):393–8.

Control CfD, Prevention. Current tobacco use among middle and high school students--United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):581.

Thomasson HR. Gender Differences in Alcohol Metabolism. In: Galanter M. et al. (eds) Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Recent Developments in Alcoholism, vol 12. Boston: Springer; 2002.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jad Chidiac, Dr. Jennyfer Hallit and Dr. Melissa Chahine for their help in the data collection, as well as all the participants who helped us during this project.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SO and SH designed the study; LN ad SO drafted the manuscript; SH, CH and PS carried out the analysis and interpreted the results; RH, MS and HS assisted in drafting and reviewing the manuscript; MA was responsible for data collection; HS edited the paper for English language. All authors reviewed the final manuscript and gave their consent.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Psychiatric Hospital of the Cross Ethics and Research Committee, in compliance with the Hospital’s Regulatory Research Protocol, approved this study protocol (HPC-012-2019). A written consent was obtained from the parents of the students before starting the data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakhoul, L., Obeid, S., Sacre, H. et al. Attachment style and addictions (alcohol, cigarette, waterpipe and internet) among Lebanese adolescents: a national study. BMC Psychol 8, 33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00404-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00404-6