Abstract

Background

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the leading causes of preventable blindness in low and middle income countries. In Nepal, there are less studies regarding DR and they too are limited around Kathmandu valley. This study was done to assess visual morbidity in patients with DR at a peripheral tertiary eye care center of Nepal.

Methods

This was a prospective, hospital based, cross-sectional study in which all consecutive cases of DR were evaluated. DR was classified according to Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group - report no. 10 Table A5–1 (Modified Airlie House Classification). Data entry and analysis was done in an SPSS unit version 20. Wherever applicable, variables were set as 100 eyes.

Results

Total number of patients included in this study was 50. Commonest age group was 50–69 yrs. (43/77 yrs.; min/max) comprising 80% of the total population (n = 50) and the predominant population was male (76%). Non proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) was found in 69%, proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) in 31% and advanced diabetic eye disease (ADED) in 3% (n = 100).

Conclusions

All the stages of DR were present at significant proportions in this study, noteworthy was the percentage of PDR. This study shows an urgency to gather a national data on DR, raise awareness among diabetics and train effective man power at a local level to diagnose DR at an early stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is emerging globally as one of the main causes of avoidable blindness and a leading cause of blindness in low and middle income countries. This might be due to industrialization, mobilization of population and changing life styles [1].

Blindness from DR can be prevented by early diagnosis, optimisation of associated risk factors and timely ocular treatment, but systematic screening for DR is rarely done in low and middle income countries (LMIC) like Nepal [2,3,4,5,6].

Various studies have been done abroad regarding DR and its awareness [7,8,9,10,11]. However in Nepal, there are only few studies and they too are limited in and around Kathmandu [3, 12,13,14,15,16]. Despite the studies being conducted in Nepal, data are still not enough to be comparable to the global scenario.

Nepal is a country located in south asia with a population of approx. 25 million [17]. Lumbini Eye Institute (LEI) is situated in the southern belt of Nepal, around 4 km away from the Indian border of Uttar Pradesh. Majority of the patients from Rupandehi and Kapilvastu (approx. 1.4 million population) district are served by LEI. Being a tertiary eye care center, it also serves a fraction of patients who are referred to LEI from further away districts for specialist care. Due to an open border between India and Nepal, a major fraction of patients from the adjoining Uttar Pradesh also visit LEI.

This study was done to enhance the existing scientific knowledge on DR and evaluate its various patterns, at a peripheral tertiary eye care center in Nepal.

Methods

This was a prospective, hospital based, cross-sectional study done between Aug 2013 to July 2014 at Lumbini Eye Institute. Ethical approval for the study was taken from Institutional Review Board of Lumbini Eye Institute. Verbal and written consent for enrolment was taken from all participants.

Non-probability, convenience sampling method was used to evaluate all consecutive cases of DR. Among them, 50 patients at any stage of DR were selected. Patients with causes other than DR for visual impairment putting diagnosis in dilemma and with poor view of fundus were excluded.

Detailed history taking of all the patients were done. Along with their demographic profile, presence of diminution of vision and duration was recorded. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was recorded using Snellen’s chart. Detailed slit lamp examination of anterior and posterior segment was done. Fundus photography and fundus fluorescein angiography was done, as appropriate. DR was classified according to Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group - report no. 10 Table A5–1 (Modified Airlie House Classification).

Data entry and analysis was done in an SPSS unit version 20. Wherever applicable, variables were set as 100 eyes.

Results

Commonest age group was 50–69 yrs. (43/77 yrs.; min/max) comprising 80% of the total population (n = 50) and the predominant population was male (76%).

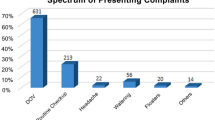

Forty two percent (n = 100) of the eyes checked had BCVA of <6/60, 48% had visual complaints for >1 yr. Only 4% (2/50) of patients sought for eye check up with no visual complaints (Table 1).

Non proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) was found in 69%, proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) in 31% and advanced diabetic eye disease (ADED) in 3% (n = 100). All the stages of DR viz. mild NPDR, moderate NPDR, severe NPDR, early PDR and high risk PDR were seen at 15%, 27%, 27%, 10% and 18%, respectively (n = 100) (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Fundus (a, b, d, f, h) and fluorescein angiography (c, e, g) photographs. (a) Moderate Non Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy, right eye; (b, c) Severe Non Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy, left eye; (d, e) Early Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy, right eye; (f, g) High risk Proliferative diabetic retinopathy, right eye; (h) Advanced Diabetic Eye Disease, left eye

Discussion

Age group and sex predilection in our study was consistent with majority of the studies. This shows that, visual morbidity increases with age and males are more susceptible [15, 16, 18,19,20,21].

Majority of the eyes checked (42%, n = 100) had decreased BCVA (<6/60) at presentation and with a longstanding visual complaints (>1 yr) in 48% of the study population. These patients presented at a very late stage of DR. Above this, only two patients (n = 50) with diabetes sought for an eye check up without any visual complaints. This suggests a lack of awareness regarding visual morbidity related to diabetes. Raising awareness about the consequences of uncontrolled or longstanding diabetes to vision in these patients could change this scenario. Also, counselling and timely referral by their treating physician could play a major role.

There are numerous studies from Nepal to assess the awareness of DR in diabetic population. From the studies on awareness done by Shrestha et al., in 2004; Paudyal G et al., in 2008, Mishra et al., in 2016; to the series of studies by Thapa R et al., from 2012 to 2015; all show decreased awareness [3, 12,13,14, 22, 23].

Hence, lack of awareness is not only a matter of concern in Nepal and LMIC, but seems to be a global issue, as suggested by various studies from abroad [7, 9, 10, 24,25,26,27].

All the stages of DR were present in our study. Percentage of PDR (31%, n = 100) and ADED (3%, n = 100) is an alarming sign for active intervention that warrants ample community based studies and programs for diagnosis of DR at an early stage. Despite a small sample size, significant proportions of DR at all stages were detected in this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this study has shown the highest percentage of PDR (31%) documented from Nepal. Level of PDR and ADED (34%), as shown in this study, suggests a major backlog of cases at a tertiary as well as primary level. Early diagnosis at the primary level, where ophthalmic assistants may play a key role, and treatment at tertiary center by retina specialists may decrease this burden.

Studies done in Nepal since 2004 till 2016 has shown the prevalence of PDR to be as low as 0.5% to as high as 25.93%. These data however, represent Kathmandu and nearby areas. Studies done outside the valley will certainly contribute to this existing pool of data. The authors would like to encourage researchers from the periphery as well, so that a national data that represents Nepal could be documented [3, 12,13,14,15,16, 23].

Conclusions

All the stages of DR were present at significant proportions in this study, noteworthy was the percentage of PDR. Attitude towards eye check up in diabetics seemed low. This shows an urgency to gather a national data on DR, raise awareness among diabetics and train effective man power at a local level to diagnose DR at an early stage.

Abbreviations

- ADED:

-

Advanced diabetic eye disease

- BCVA:

-

Best corrected visual acuity

- DR:

-

Diabetic Retinopathy

- NPDR:

-

Non proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- PDR:

-

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

References

WHO | Prevention of blindness from diabetes mellitus. WHO Available at: http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/prevention_diabetes2006/en/. Accessed 27 Dec 2016.

Diabetic Retinopathy PPP - Updated 2016. American Academy of Ophthalmology (2016). Available at: https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/diabetic-retinopathy-ppp-updated-2016. Accessed 27 Dec 2016.

Thapa R, Poudyal G, Maharjan N, Bernstein PS. Demographics and awareness of diabetic retinopathy among diabetic patients attending the vitreo-retinal service at a tertiary eye care center in Nepal. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2012;4:10–6.

International Council of Ophthalmology:Enhancing Eye Care:Diabetic Eye Care. Available at: http://www.icoph.org/enhancing_eyecare/diabetic_eyecare.html. Accessed 8 May 2017.

Singh R, Ramasamy K, Abraham C, Gupta V, Gupta A. Diabetic retinopathy: an update. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:179–88.

Lee R, Wong TY, Sabanayagam C. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema and related vision loss. Eye Vis. 2015;17(2):2–25.

Hussain R, Bindu R, Anantharaman G, Gopalakrishnan M, Sadasivan S, James J, et al. Knowledge and awareness about diabetes mellitus and diabetic retinopathy in suburban population of a south Indian state and its practice among the patients with diabetes mellitus: a population-based study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64(4):272–6.

Al Zarea BK. Knowledge, attitude and practice of diabetic retinopathy amongst the diabetic patients of AlJouf and Hail Province of Saudi Arabia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(5):5–8.

Mohammed I, Waziri AM. Awareness of diabetic retinopathy amongst diabetic patients at the murtala mohammed hospital, Kano. Nigeria Niger Med J. 2009;50(2):38–41.

Tajunisah I, Wong P, Tan L, Rokiah P, Reddy S. Awareness of eye complications and prevalence of retinopathy in the first visit to eye clinic among type 2 diabetic patients. Int. J Ophthalmol. 2011;4(5):519–24.

Huang OS, Tay WT, Tai ES, Wang JJ, Saw SM, Jeganathan VS, et al. Lack of awareness amongst community patients with diabetes and diabetic retinopathy: the Singapore Malay eye study. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2009;38(12):1048–55.

Shrestha S, Malla OK, Karki DB, Byanju RN. Retinopathy in a diabetic population. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2007;5(2):204–9.

Thapa R, Joshi DM, Rizyal A, Maharjan N, Joshi RD. Prevalence, risk factors and awareness of diabetic retinopathy among admitted diabetic patients at a tertiary level hospital in Kathmandu. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2014;6(1):24–30.

Paudyal G, Shrestha M, Meyer JJ, Thapa R, Gurung R, Ruit S. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy following a community screening for diabetes. Nepal Med Coll J. 2008;10(3):160–3.

Shrestha MK, Paudyal G, Wagle RR, Gurung R, Ruit S, Onta SR. Prevalence of and factors associated with diabetic retinopathy among diabetics in Nepal: a hospital based study. Nepal Med Coll J. 2007;9(4):225–9.

Thapa SS, Thapa R, Paudyal I, Khanal S, Aujla J, Paudyal G, et al. Prevalence and pattern of vitreo-retinal diseases in Nepal: the Bhaktapur glaucoma study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013;13(9):2–8.

Population Profile of Nepal | Central Bureau of Statistics. Available at: http://cbs.gov.np/sectoral_statistics/population/population_profile. Accessed 10 Sept 2017.

Varma R, Macias GL, Torres M, Klein R, Pena FY, Azen SP, et al. Biologic risk factors associated with diabetic retinopathy: the Los Angeles Latino eye study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(7):1332–40.

Rema M, Premkumar S, Anitha B, Deepa R, Pradeepa R, Mohan V. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in urban India: the Chennai urban rural epidemiology study (CURES) eye study, I. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(7):2328–33.

Raman R, Ganesan S, Pal SS, Kulothungan V, Sharma T. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in rural India. Sankara Nethralaya diabetic retinopathy epidemiology and molecular genetic study III (SN-DREAMS III), report no 2. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2014;2(1):e000005.

Chatziralli IP, Sergentanis TN, Keryttopoulos P, Vatkalis N, Agorastos A, Papazisis L. Risk factors associated with diabetic retinopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:153.

Thapa R, Bajimaya S, Paudyal G, Khanal S, Tan S, Thapa SS, et al. Population awareness of diabetic eye disease and age related macular degeneration in Nepal: the Bhaktapur retina study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:188.

Mishra S, Pant B, Subedi P. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among known diabetic population in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2016;14(2):134–9.

Dandona R, Dandona L, John RK, McCarty CA, Rao GN. Awareness of eye diseases in an urban population in southern India. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(2):96–102.

Murugesan N, Snehalatha C, Shobhana R, Roglic G, Ramachandran A. Awareness about diabetes and its complications in the general and diabetic population in a city in southern India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77(3):433–7.

Prabhu M, Kakhandaki A, Chandra KP. Pramod. A hospital based study on awareness of diabetic retinopathy in diabetic individuals based on knowledge, attitude and practices in a tier-2 city in South India. IJCEO. 2015;1(3):159–63.

Pan CW, Wang S, Qian DJ, Xu C, Song E. Prevalence, awareness, and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy among adults with known type 2 diabetes mellitus in an Urban Community in China. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017;24(3):188–94.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. Shakti Shrestha for his contributions during the preparation of the manuscript and data analysis.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP was involved in conception, design, data collection, literature review, manuscript preparation and data analysis. GL, RK, SKC and AMB was involved in drafting the manuscript and critical revision for intellectual content. DB was involved in literature review and manuscript preparation. NG was involved in manuscript preparation, data analysis and critical revision for intellectual content. All authors have equally contributed for the research. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was taken from the Institutional Review Board of Lumbini Eye Institute and oral as well as written consent was taken from all the patients for their enrolment into the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pandey, A., Lamichhane, G., Khanal, R. et al. Assessment of visual morbidity amongst diabetic retinopathy at tertiary eye care center, Nepal: a cross-sectional descriptive study. BMC Ophthalmol 17, 263 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-017-0656-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-017-0656-3