Abstract

Objective

Pembrolizumab has become an integral first line therapeutic agent for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but its potential predictive role in clinical and molecular characteristics remains to be clarified. Accordingly, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the clinical benefit of pembrolizumab in treatment of first line NSCLC and to select individuals with the greatest potential benefit from pembrolizumab therapy, in order to obtain a more accurate treatment of NSCLC in immunotherapy.

Methods

Mainstream oncology datasets and conferences were searched for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) published before August 2022. RCTs involved individuals with first line NSCLC treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy. Two authors independently selected the studies, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias. The basic characteristics of the included studies were recorded, along with 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) and hazard ratios (HR) for all patients and subgroups. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS), and secondary endpoints was progression-free survival (PFS). Pooled treatment data were estimated using the inverse variance-weighted method.

Results

Five RCTs involving 2,877 individuals were included in the study. Pembrolizumab-based therapy significantly improved OS (HR 0.66; CI 95%, 0.55–0.79; p < 0.00001) and PFS (HR 0.60; CI 95%, 0.40–0.91; p = 0.02) compared with chemotherapy. OS was substantially enhanced in individuals aged < 65 years (HR 0.59; CI 95%, 0.42–0.82; p = 0.002), males (HR 0.74; CI 95%, 0.65–0.83; p < 0.00001), with a smoking history (HR 0.65; CI 95%, 0.52–0.82; p = 0.0003), with PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) < 1% (HR 0.55; CI 95%, 0.41–0.73; p < 0.0001) and TPS ≥ 50% (HR 0.66; CI 95%, 0.56–0.76; p < 0.00001), but not in individuals aged ≥ 75 years (HR 0.82; CI 95%, 0.56–1.21; p = 0.32), females (HR 0.57; CI 95%, 0.31–1.06; p = 0.08), never smokers (HR 0.57; CI 95%, 0.18–1.80; p = 0.34), or with TPS 1–49% (HR 0.72; CI 95%, 0.52–1.01; p = 0.06). Pembrolizumab significantly prolonged OS in NSCLC patients, regardless of histology type (squamous or non-squamous NSCLC), performance status (PS) (0 or 1), and brain metastatic status (all p < 0.05). Subgroup analysis revealed that pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy had more favorable HR values than pembrolizumab monotherapy in improving the OS of individuals with different clinical and molecular features.

Conclusion

Pembrolizumab-based therapy is a valuable option for first line treating advanced or metastatic NSCLC. Age, sex, smoking history and PD-L1 expression status can be used to predict the clinical benefit of pembrolizumab. Cautiousness was needed when using pembrolizumab in NSCLC patients aged ≥ 75 years, females, never smokers, or in patients with TPS 1–49%. Furthermore, pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy may be a more effective treatment regimen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer has long been the principal cause of cancer morbidity and mortality worldly [1]. Approximately 85% of all lung cancers are non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) [2]. Immunotherapy based on immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has been an indispensable therapeutic method after surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy in the past 20 years and has been included in the 1st-line therapy for various malignancies [3,4,5,6,7]. The methods of immunotherapy for cancer include a variety of drugs recently developed to stimulate the immune system of patients and destroy tumor cells [8]. Among the many immune checkpoint pathways, the PD-1 receptor pathway is the most prominent in cancer treatment, through which anti-tumor immune activity is reduced. The PD-1 receptor exists on the surface of activated T cells surface [3, 9], which prevents tissue damage resulting from chronic inflammation and adjusts immune tolerance [10]. Programmed death ligands 1 and 2 (PD-L1 and PD-L2) interact with PD-1 to reduce T-cell receptor signal transduction and downregulate T-cell activation, proliferation, and T-cell-mediated anti-tumor response [11,12,13]. Pembrolizumab is a potent and highly selective IgG4-κ humanized anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody that has been presently approved for the treatment of a variety of neoplasms, involving NSCLC, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin, melanoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), urothelial cell and microsatellite instability (MSI) high cancer [14,15,16]. Pembrolizumab has a high affinity for the PD-1 receptor and a significant inhibitory effect on ligand interactivity and activity [17]. Results from several large clinical trials have shown the benefits of pembrolizumab for overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in advanced NSCLC [15, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

However, only a subset of patients with NSCLC would benefit from pembrolizumab treatment, and it is important to identify which group of patients has a greater chance of benefit. In this way, the benefit population can be screened, and on the other hand, the additional toxic side effects caused by unnecessary drug use can be reduced [26, 27]. PD-L1 expression determined by immunohistochemistry is one of the most influential biomarkers for detecting the efficacy of pembrolizumab. However, the detection reagent and platform are difficult to unify, and the puncture tissue size of many advanced patients is small and limited, which may affect the application of combined positive scores (CPS) or tumor proportion scores (TPS). Therefore, diagnostic accuracy may be limited. Additionally, some trials have shown that PD-L1 expression does not accurately identify individuals who are sensitive to immunotherapy. ICIs may be beneficial to individuals with negative PD-L1 expression [28, 29], and their accuracy in predicting response to immunotherapy is not ideal. Another promising biomarker is tumor mutational burden (TMB), however, its predictive efficacy remains controversial [30].

Current treatment options for individuals with advanced NSCLC have not yet met medical needs, especially those with recurrent or metastatic diseases. Although pembrolizumab-based therapy may have a strong and lasting tumor response, on the one hand, due to the lack of reliable biomarkers to predict the prognosis of individuals, the further clinical application of pembrolizumab is still a major challenge; on the other hand, because pembrolizumab is associated with specific adverse events, efforts are being made to identify predictable biomarkers to select individuals who obtain the greatest potential benefits from immunotherapy treatment. We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to analyze the impact of different clinical and molecular characteristics on the clinical benefit of pembrolizumab first line treatment in individuals with NSCLC to determine the appropriate biomarkers and guide the choice of treatment. We have provided a follow-up article in light of the PRISMA Reporting Checklist.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were selected according to the PICOs principle (participants, intervention, comparison, and outcomes). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) pembrolizumab monotherapy or combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy for first line NSCLC individuals, and (II) OS and/or PFS available for each clinical and molecular feature subgroup. The exclusion criteria were: (I) pembrolizumab combined with anti-CTLA-4, antiangiogenic, radiotherapy or other specific therapy, (II) survival data were incomplete, (III) the control group only took placebo, (IV) if multiple articles were reported on the same RCTs, we selected the most recent, comprehensive data and the longest follow up, (V) if different articles in the same RCT looked at different subgroups, we brought into them all.

Literature searching and data collecting

We searched for the target literature through PubMed, Embase Science Direct, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane library, as well as the minutes of main oncology meetings. The primary search terms were NSCLC, pembrolizumab, and a randomized controlled trial, supplemented by other terms. The literature was published prior to August 2022. The authors (WJL and GWH) independently selected the literature and extracted data from those studies. The third author (PC) resolved these differences. The title, first author, year of publication, study phase, line of therapy, study design, blinding, and survival outcomes were recorded.

Quality assessment and statistical analyses

Quality assessment was independently evaluated by two authors (WJL and GWH) using the Cochrane bias tool. The primary endpoint was OS, and secondary endpoints was PFS. The chi-square test and I2 statistics were used to assess heterogeneity. Both I2 < 50% and p > 0.10 was regarded as heterogeneity-acceptable, employing the fixed-effect model; otherwise, the random-effect model was employed. Aggregated assessments, together with confidence intervals (CI) 95% and hazard ratios (HR) for all patients and subgroups were displayed using forest plots. Review Manager 5.3 was used for data statistics. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The literature was excluded individually for sensitivity analyses.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

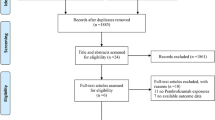

In total, 2,120 articles were obtained from the database. Figure 1 illustrated the filtering process. After filtering, 2,115 articles were excluded. Ultimately, 2,877 patients from five RCTs were included in our meta-analysis (Table 1). The included RCTs included one phase II [25], and four phase III RCTs [15, 19,20,21,22,23], published between 2016 and 2021. All RCTs had a low risk of bias, according to the risk of bias analysis (Fig. 2).

Effects of pembrolizumab in NSCLC

Our meta-analysis revealed that pembrolizumab-based first line therapy significantly improved patients’ OS (HR 0.66; CI 95%, 0.55–0.79; p < 0.00001) (Fig. 3A) and PFS (HR 0.60; CI 95%, 0.40–0.91; p = 0.02) (Fig. 3B) compared with chemotherapy in five studies, respectively.

Effects of pembrolizumab by age group

OS was significantly improved by pembrolizumab-based first line therapy versus chemotherapy in individuals aged < 65 years (HR 0.59; CI 95%, 0.42–0.82; p = 0.002) and ≥ 65 years (HR 0.68; CI 95%, 0.54–0.85; p = 0.0008). Surprisingly, we found no OS benefit in patients aged ≥ 75 years (HR 0.82; CI 95%, 0.56–1.21; p = 0.32) (Fig. S1A). Subgroup analysis revealed that the regimen of treatment did not affect OS improvement in individuals aged < 65 or ≥ 65 years (Table 2). In terms of PFS data from four studies, pembrolizumab significantly enhanced PFS versus chemotherapy in patients aged < 65 years (HR 0.48; CI 95%, 0.40–0.58; p < 0.00001) and ≥ 65 years (HR 0.63; CI 95%, 0.52–0.76; p < 0.00001) (Figure S2A and Table S1). No PFS data were available for the analysis of patients aged ≥ 75 years.

Effects of pembrolizumab by gender

Pembrolizumab significantly enhanced OS for the first line treatment in male (HR 0.74; CI 95%, 0.65–0.83; p < 0.00001), but not in female individuals (HR 0.57; CI 95%, 0.31–1.06; p = 0.08) compared with chemotherapy (Fig. S1B). Subgroup analysis showed that pembrolizumab as combination therapy (HR 0.70; CI 95%, 0.56–0.88; p = 0.002) improved the survival of individuals, but not as monotherapy in male individuals. In female individuals, subgroup analysis showed that pembrolizumab as combination therapy (HR 0.32; CI 95%, 0.23–0.46; p < 0.00001) improved the survival of individuals, but not as monotherapy (Table 2). PFS was substantially improved in both male (HR 0.55; CI 95%, 0.43–0.71; p < 0.00001) and in female individuals (HR 0.51; CI 95%, 0.35–0.74; p = 0.0004) (Figure S2B and Table S1).

Effects of pembrolizumab by histomorphological subtypes

OS was significantly enhanced by pembrolizumab in first line therapy versus chemotherapy in both squamous (HR 0.71; CI 95%, 0.60–0.83; p < 0.0001) and non-squamous NSCLC (HR 0.68; CI 95%, 0.52–0.87; p = 0.002) (Fig. S1C). In non-squamous cell carcinoma, the analysis of subgroup by treatment regimen indicated that patients with pembrolizumab as combination therapy had a better survival (HR 0.59; CI 95%, 0.48–0.72; p < 0.00001), while patients treated with pembrolizumab as monotherapy had no substantial difference in survival compared with those who received chemotherapy. Subgroup analysis showed that both pembrolizumab monotherapy and combined chemotherapy prolonged the survival of individuals in squamous NSCLC (Table 2). PFS was also significantly improved in squamous (HR 0.54; CI 95%, 0.44–0.66; p < 0.00001) and non-squamous NSCLC individuals (HR 0.50; CI 95%, 0.43–0.58; p < 0.00001) (Figure S2C and Table S1).

Effects of pembrolizumab by ECOG PS score

Pembrolizumab significantly enhanced OS versus chemotherapy in both individuals with performance status (PS) 0 (HR 0.67; CI 95%, 0.54–0.83; p = 0.0002) and PS 1 (HR 0.66; CI 95%, 0.52–0.83; p = 0.0005) (Fig. S1D). The analysis of the subgroup by the treatment regimen revealed that patients with PS 0 who received pembrolizumab as combination therapy had a better survival (HR 0.48;CI 95%, 0.33–0.69; p = 0.0001), but those who received monotherapy based on pembrolizumab did not. Subgroup analysis revealed that pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy prolonged the survival of individuals with PS 1 (HR 0.59;CI 95%, 0.47–0.74; p < 0.00001), but in monotherapy (Table 2). PFS was also substantially enhanced in patients for PS 0 (HR 0.47; CI 95%, 0.37–0.59; p < 0.00001) and PS 1 (HR 0.57; CI 95%, 0.49–0.67; p < 0.00001) (Figure S2D and Table S1).

Effects of pembrolizumab by smoking status

Findings revealed that pembrolizumab-based 1st-line therapy provided a longer OS in individuals with a smoking history (HR 0.65; CI 95%, 0.52–0.82; p = 0.0003), but not in never smokers (HR 0.57; CI 95%, 0.18–1.80; p = 0.34) compared with chemotherapy (Fig. S1E). Patients with a smoking history had OS benefits regardless of the treatment regimen. In patients who had never smoked, pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy improved survival (HR 0.23; CI 95%, 0.10–0.54; P = 0.0007), whereas monotherapy did not (Table 2).

Effects of pembrolizumab by brain metastatic status

OS was significantly improved by pembrolizumab-based 1st-line therapy compared to chemotherapy in both individuals with brain metastases (HR 0.44; CI 95%, 0.27–0.70; p = 0.0006) and without brain metastases (HR 0.60; CI 95%, 0.50–0.73; p < 0.00001) (Fig. S1F). Subgroup analyses showed that only pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy prolonged survival among patients with brain metastasis (HR 0.41; CI 95%, 0.24–0.67; p = 0.0005), but pembrolizumab monotherapy did not prolong survival. The treatment regimen did not affect OS improvement in individuals without brain metastasis (Table 2). Similarly, PFS was also substantially enhanced in patients with brain metastases (HR 0.44; CI 95%, 0.29–0.67; p = 0.0001) and without brain metastases (HR 0.49; CI 95%, 0.41–0.58; p < 0.00001) (Figure S2E and Table S1).

Effects of pembrolizumab by PD-L1 tumor proportion score

OS was obviously prolonged by pembrolizumab for first line therapy compared with chemotherapy in individuals with PD-L1 TPS < 1% (HR 0.55; CI 95%, 0.41–0.73; p < 0.0001), TPS ≥ 1% (HR 0.71; CI 95%, 0.58–0.87; p = 0.001), and TPS ≥ 50% (HR 0.66; CI 95%, 0.56–0.76; p < 0.00001), while not in individuals with TPS 1–49% (HR 0.72; CI 95%, 0.52–1.01; p = 0.06) (Fig. S1G). Subgroup analysis revealed that for patients with TPS < 1%, 1st-line combined therapy had OS benefits, and there were no relevant data based on monotherapy. The analysis of subgroups by treatment regimen revealed that for patients with TPS 1–49%, the pooled HR involving three studies based on pembrolizumab combined chemotherapy was 0.60 (CI 95% 0.44–0.81; p = 0.0007). Only one research was referred to the monotherapy, with the HR of 0.92 (CI 95% 0.77–1.11; p = 0.40). Patients with TPS ≥ 1% and ≥ 50% had OS benefits regardless of the regimen of therapy (Table 2). PFS was significantly improved in patients with PD-L1 TPS < 1% (HR 0.66; CI 95%, 0.52–0.84; p = 0.0008), TPS 1–49% (HR 0.53; CI 95%, 0.42–0.69; p < 0.00001), and TPS ≥ 50% (HR 0.50; CI 95%, 0.32–0.76; p = 0.001) (Figure S2F and Table S1).

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

The literature was excluded individually for sensitivity analyses, revealing that the main outcomes after excluding this research did not differ substantially from past outcomes, indicating low sensitivity, credibility, and robustness of the outcomes (Table S2). These sensitivity analyses did not alter the prognostic factors in the entire cohort. Furthermore, no obvious publication bias was discovered based on the funnel plots of OS and PFS (Figure S3) and the funnel plots of OS and PFS for each subgroup (Figure S4 and S5).

Discussion

The success of PD-1 inhibitors in the treatment of NSCLC was a vital milepost in the history of tumor treatment [31], which has been shown to have long-lasting anti-tumor efficacy and has significantly revolutionized the therapeutic paradigm of advanced/metastatic NSCLC [32,33,34,35]. Pembrolizumab strongly inhibits the PD-1/PD-L1 immune signaling pathway. This prospective neobiological drug has rightfully earned its place as one of the most successful new therapies for cancer. Better efficiency and treatment tolerance demonstrated that pembrolizumab was superior to chemotherapy [36,37,38,39]. Although a crucial breakthrough has been made, this persistence only reaches a few patients (about 20%) [40] and pembrolizumab was associated with specific adverse events, which highlights the urgency of biomarkers to predict the long-term clinical benefit of treatment. The expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells was related to clinical benefits and currently routinely serves as a biomarker in the clinical practice of NSCLC [36]. Nonetheless, PD-L1 remains a defective biomarker because a few high expression individuals are non-responsive, whereas PD-L1 negative or low expression individuals are usually observed to be responsive. In NSCLC, TMB was also related to PFS and objective response rate (ORR) with anti-PD-1 antibodies [41, 42]. The use of TMB in clinical practice demands constant efforts to reconcile quantitative calculation methods, solutions for the rapid return of results, costs, and intratumoral and inter-tumor heterogeneity. To date, the association of TMB with OS has either gone undetected or has been limited to relatively short followings [43, 44]. Studies on tumor specimens from melanoma patients have shown that the response to PD-1/L1 blockers was dependent on tumor infiltration of activated CD8+ T effector cells prior to treatment [45]. The impact of CD4+ T lymphocytes in the treatment of PD-1 inhibitors has not been well studied, and there was no clear correlation yet. Therefore, the predictive value of biomarkers such as CD4+, CD8+, PD-L1, and TMB for PFS and OS in patients with NSCLC receiving anti-PD-1 antibodies was limited. In addition, many biomarkers have been proposed to determine the therapeutic effect of pembrolizumab treatment, such as tumor size, albumin, lymphocyte count, and lactate dehydrogenase level [41, 46,47,48,49], however, none of these biomarkers accurately predicted the efficacy of pembrolizumab. The demand for a robust, non-invasive biomarker to predict the clinical benefit of pembrolizumab for first line treatment in patients with advanced NSCLC was still lacking. The development of reliable biomarkers to accurately identify individuals who could benefit from immunosuppressive agents is essential for optimizing the treatment of advanced NSCLC and selecting the most effective treatment to maximize clinical benefit.

A total of 2,877 patients from five RCTs were included in our meta-analysis. Our meta-analysis revealed that pembrolizumab was an effective treatment for NSCLC in first line. The pooled estimate for both OS and PFS was substantially improved compared with chemotherapy. Did pembrolizumab have a positive effect on patients with different clinical characteristics? We further searched for the dominant population using a subgroup analysis. To the best of our knowledge, our study was one of the largest meta-analyses to explore the efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with NSCLC with different clinical features.

Age is a well-known hazard factor for carcinoma occurrence and progression [50], and is associated with poor prognosis [51, 52]. Similarly, if elderly patients benefit less from ICIs, then age related changes in the immune system may result in a decline in immune function, which has also triggered debate [53, 54]. Age was reported to be related to changes in the immune system [55, 56], which may alter cytokine dynamics [57] and reduce CD8+ T-cell proliferation [58]. This has also been associated with reduced T-cell function [59], CD28 expression [60, 61], and costimulatory signals for T-cell activation [62]. However, Elias et al. [63] discussed the clinical benefit and safety of PD-1/L1 inhibitors in patients with NSCLC, melanoma, and kidney carcinoma and observed no significant age-related differences in OS and side effects between older and younger individuals in clinical trials. This finding was consistent with the results of our study. Interestingly, in patients aged ≥ 75 years, pembrolizumab did not result in better OS than chemotherapy. This result was inconsistent with the results of a recently published study that found that among patients with NSCLC aged > 75 years, pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy achieved longer OS and PFS [64]. Comparing the results of our meta-analysis, we enrolled patients aged ≥ 75 years who were all treated with 1st-line pembrolizumab monotherapy, whereas in the study by Yang et al., all patients were treated with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy. This may have contributed to the different results, but the study also points out that pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy leading to treatment discontinuation (26% vs. 5%) caused by adverse events was higher than that of chemotherapy. Therefore, pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy should be prioritized based on close monitoring of adverse reactions in patients aged ≥ 75 years. In addition, according to existing knowledge in this field, a substantial reduction in OS with ICIs was found in patients with cancer aged ≥ 75 years. This may be due to genetic changes in tumor cells and the activation of tumorigenic signals, which initiate inflammation, angiogenesis, or metabolic changes, eventually leading to immune resistance or evasion [65,66,67].

Differences in the immune systems of males and females may be associated with the natural process of chronic inflammatory diseases such as tumors [68, 69]. Gender differences in the efficacy of immunotherapy on PFS/OS were also explored, and the improvement in OS with pembrolizumab differed significantly between male and female patients with male patients appearing to benefit more from pembrolizumab treatment than women. This may be due to the fact that female tumors must avoid more effective immune surveillance mechanisms and undergo more intensive immune editing processes to metastasize [70]. This ability of female tumors to escape immune surveillance may reduce the immunogenicity of advanced female tumors, and the immune escape mechanism is stronger than that of similar tumors in males [71]. Therefore, these cells may be more resistant to immunotherapy. Second, a higher TMB was a powerful predictor of the benefits of ICIs [72]. TMB was significantly higher in male patients with multiple tissue types, including melanoma and NSCLC [73,74,75]. It is important to note that complex interactions among genes, hormones, environment, and symbiotic microbiome components may also affect the gender response to pembrolizumab-based treatment [76,77,78,79,80]. Furthermore, it has also been shown that EGFR mutant type NSCLC tumors are significantly less sensitive to ICIs than EGFR wild type NSCLC tumors, and are more common in female patients than in male patients [81].

The approval of pembrolizumab as an anti-PD-1 antibody in the 1st-line therapy for advanced/metastatic NSCLC with PD-L1 ≥ 50% (all histologies) provided direction for a new therapeutic option for patients with squamous cell carcinoma, accounting for approximately 25–30% of cases [82, 83]. Compared with non-squamous NSCLC, patients with squamous histological type are usually older at diagnosis and have advanced disease [84, 85], have a higher incidence of comorbidity [86, 87] and are more likely to invade larger vessels [88,89,90]. In addition, mutations approved for targeted therapy were rare in squamous NSCLC [91,92,93,94,95]. Therefore, treatment options for improving the prognosis of these patients were limited, especially the 1st-line options for advanced stages [96, 97]. In our analysis, pembrolizumab exhibited longer OS than chemotherapy in individuals with squamous and non-squamous NSCLC, suggesting that histology may not be a prognostic factor or predictor of clinical efficacy outcomes. Meanwhile, individuals with both squamous and non-squamous NSCLC benefit from 1st-line treatment, which provided an early treatment regimen [98]. It should be pointed out that although < 30% of individuals who meet the pembrolizumab therapy conditions may have enhanced survival, the present guidelines still recommend 1st-line platinum-based dual chemotherapy for the majority of treatment-naive individuals, even those with PS 0 and 1 [99,100,101,102,103]. For individuals with PS 2 or elderly patients, systemic treatment was recommended because of possible comorbidity and toxicity [96, 97], but there was evidence that individuals with PS 2 complicated with diseases or elderly patients usually did not receive chemotherapy [104,105,106]. The benefit of pembrolizumab observed in individuals with squamous NSCLC was significant and may promote better survival outcomes. Therefore, could pembrolizumab be a promising alternative to chemotherapy for these patients?

At present, the evaluation of PS should not be ignored as an important decision parameter when patients with advanced cancer choose treatment. The ECOG PS guidance for clinicians was a more reliable reflection of the real condition than biological age. This was widely supported in the literatures [107,108,109,110]. Meanwhile, a good PS (0 or 1) may play a vital role in guiding treatment decisions for NSCLC [111]. Previous studies have shown that earlier pembrolizumab treatment most likely confers the maximum survival benefit among individuals with PS of 0 and 1. Immunotherapy was also often the preferred option in practice for individuals with PS 0 and 1, who were not receiving 1st-line pembrolizumab therapy, and whose disease has progressed after 1st-line chemotherapy [112]. Most RCTs on pembrolizumab have included only patients with NSCLC with an ECOG PS of 0 or 1. We did not consider pembrolizumab as a treatment option for patients with PS ≥ 2, because the extent of the benefit was unclear. To achieve optimal use of pembrolizumab in clinical practice and improve patient outcomes, we investigated whether ECOG PS could be used as a potential biomarker to predict pembrolizumab clinical benefit. Our results indicated that early treatment with pembrolizumab improved OS in both individuals with PS 0 and 1, and that combined chemotherapy provided further OS benefits. Similar conclusions have been drawn for other immunotherapies such as atezolizumab and nivolumab [113, 114]. In addition, Ksienski et al. revealed that individuals with ECOG PS 2 or 3 had a higher rate of serious adverse effects after pembrolizumab treatment compared to patients with ECOG PS 0/1 [115]. Pembrolizumab should be carefully considered when considering treatment for patients with poor ECOG PS. To determine the definite efficacy of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy, subsequent RCTs in individuals with an ECOG PS of 2 or 3 are required.

Smoking status was highly correlated with the incidence of NSCLC and has an obvious effect on the efficacy and tolerance of many lung cancer drugs [116]. In terms of immunotherapy, Li et al. [117] and Lee et al. [118] showed that smoking status affects the survival benefit of patients. We assessed the association between smoking status and survival benefits in NSCLC patients treated with pembrolizumab. Similar studies have been conducted in previous meta-analyses; however, there was a lack of detailed subgroups and multiple PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors involved [117, 119, 120]. Our results show that compared with chemotherapy, the use of pembrolizumab significantly prolonged the survival of former and current smokers with NSCLC but did not improve the survival of patients who never smoked. This result was similar to that of Kim et al., who observed that ICIs had a substantially longer OS than chemotherapy in individuals with a history of smoking, but no benefit was found in individuals who had never smoked [121]. Other studies have shown that the ORR was substantially higher in non-squamous NSCLC individuals with a smoking history than in never-smokers (21.5% vs. 9.2%, p = 0.0001) when treated with nivolumab [122]. This may be because, firstly, smoking could significantly increase TMB [123], making tumors more immunogenic, thus increasing the anti-tumor effect of pembrolizumab [41]. Secondly, smokers and non-smokers have different molecular profiles of lung cancer as well as different tumor microenvironments [124], which may also influence the susceptibility of patients to pembrolizumab treatment. Thirdly, smoking promotes tumorigenesis by allowing pulmonary epithelial cells to evade adaptive immunity. The carcinogen benzoapyrene (BAP) can also induce PD-L1 expression in pulmonary epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo, and PD-1 inhibitors can significantly inhibit BAP-induced lung cancer [125]. However, further subgroup analysis found that in the pembrolizumab combined chemotherapy group, patients who never smoked also gained survival benefits. Thus, we believe that chemotherapy may have increased the efficacy of pembrolizumab in the combination therapy group, which requires further experimental confirmation. In summary, smoking status should be fully considered during treatment, and combined treatment may be more effective for patients with NSCLC who never smoke. In addition, studies have shown that recurrent molecular alterations were frequently detected in never-smokers, and activated T-cell therapy may be a possible strategy for treating patients with lung cancer [126, 127]. Therefore, the smoking status appears to be an appropriate biomarker.

NSCLC accounts for approximately 80% of all lung cancer cases, and nearly half of patients with NSCLC have distant metastases at their initial diagnosis. The brain is one of the most common metastatic sites [128]. Approximately one-third of individuals with advanced NSCLC have brain metastasis [129]. The prognosis of patients with NSCLC after the diagnosis of brain metastasis was consistently poor, with an estimated median OS of 7.8 months [130]. Previous RCTs of pembrolizumab administered to individuals with advanced NSCLC have reported good activity and some long-lasting system responses [36]. However, trials using these and other ICIs typically exclude patients with brain metastases. Our analysis specifically targeted pembrolizumab in individuals with untreated advanced NSCLC, in which patients with NSCLC with or without brain metastasis benefited from pembrolizumab treatment, underscoring the potential activity of pembrolizumab in individuals with central nervous system diseases. Further subgroup analysis showed that both pembrolizumab monotherapy and combined chemotherapy prolonged the OS in patients without brain metastases. Some studies have shown that individuals with brain metastases from NSCLC could benefit from immunotherapy either as monotherapy [15] or in combination with chemotherapy [19, 20]. However, we did not observe any benefit of pembrolizumab as a 1st-line monotherapy in NSCLC patients with brain metastasis, while individuals were observed to mainly benefit from pembrolizumab-based early combination therapy. This may be due to the disruption of the blood–brain barrier and the formation of new blood vessels that enable chemotherapy to pass through the brain [131]. In preclinical studies, chemotherapy drugs showed immune regulatory properties that could increase tumor immunogenicity [132,133,134]. Therefore, pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy appears to be more effective in patients with brain metastasis. Moreover, our findings correspond with a real-world study that assessed the efficacy of pembrolizumab plus carboplatin and pemetrexed in individuals with advanced non-squamous NSCLC with or without brain metastasis, and the combined activity of the two groups was demonstrated [135].

PD-L1 is expressed in tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating immune cells [136]. The combination of PD-L1 with the PD-1 receptor on activated T-cells reduces the immune response of T cells and prevents tumor cell eradication [137, 138]. Besides playing a central role as a critical factor in current immunotherapy regimens, PD-L1 has also been demonstrated in several studies to emerge as a potential prognostic biomarker that can predict which individuals with NSCLC were more responsive to ICIs [139,140,141,142,143,144]. Our study specifically targeted the impact of PD-L1 expression in the treatment of pembrolizumab, similarly, suggesting that the expression status of PD-L1 appeared to be a significant biomarker for predicting pembrolizumab efficacy. Furthermore, we found that when treated with a single drug (individuals with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50%) and combined chemotherapy (regardless of tumor cell PD-L1 expression) for advanced or metastatic NSCLC, pembrolizumab increased the OS compared to platinum-based chemotherapy. It should be noted that the application of pembrolizumab as a monotherapy to improve survival in individuals with negative PD-L1 expression is not recommended because of the lack of experimental results and data support. It could be seen that when TPS ≥ 50%, pembrolizumab showed a more stable survival improvement. Previous studies have shown that PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% was related to a statistically substantial improvement in survival compared to individuals with lower PD-L1 expression in NSCLC [15, 145, 146]. For the 1st-line therapy of patients with metastatic NSCLC receiving pembrolizumab monotherapy, TPS ≥ 1% (preferably TPS ≥ 50%) was required to initiate treatment. PD-L1 was a continuous variable related to ICI; the higher the expression, the higher the possibility of a reaction. However, in some patients, the high expression itself was not enough to react with pembrolizumab, while in other patients, although the expression was very low, the reaction does occur. This may be explained by the multiple parameters that influence the anti-tumor immune response. Patients with some favorable parameters, such as normal LDH, normal CRP, and lower TMB (such as early stage disease), may have fewer immune responses influenced by PD-L1 expression [147]. In addition, factors such as the diversity of PD-L1 antibodies and platforms, diversity of tissue processing methods, heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression within the same cancer, and heterogeneity between primary cancer metastasis showed that PD-L1 expression was obviously imperfect as a biomarker for pembrolizumab treatment [148].

Our meta-analysis revealed that the OS benefit was not affected by histology type, ECOG PS score, or brain metastatic status. The PFS benefit was not affected by age, sex, histology type, ECOG PS score, or brain metastatic status. In addition, we found that pembrolizumab combination chemotherapy possessed a more beneficial HR value than pembrolizumab monotherapy in improving patient OS, and we recommend that pembrolizumab-based combination therapy is preferred for NSCLC in clinical applications.

Although our results provided some useful conclusions, we acknowledge the following limitations. Firstly, the data came from published articles with prearranged subgroups that were not obtained from the characteristics of the individual patients themselves. Therefore, some potential variants (such as TMB) were omitted from our analysis, which could lead to differences between our results on the clinical activity of pembrolizumab and the current results, which would cause some imprecision in the results and potential bias. Therefore, our subgroup analysis findings were still enlightening but were not conclusive. Secondly, some of the results with heterogeneous due to the fact that patients in a subgroup had diversity clinical and molecular characteristics, and the results about the biomarkers were somewhat scattered. For example, PD-L1 expression in tumors, which was distributed differently between the sexes, may influence pembrolizumab response. Thirdly, despite our comprehensive and systematic search in mainstream databases, the number of retrieved articles was still relatively small, and some subgroup analyses performed in this study included only a few trials. It could not be ruled out that insufficient statistical power may explain the results obtained from these subgroup analyses. Therefore, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results. Fourthly, we have not compared the clinical benefit of pembrolizumab monotherapy versus pembrolizumab combined with platinum-based chemotherapy. Further research is needed using the method of network meta-analysis. Fifthly, the majority of studies have demonstrated a rapid decline in PFS and OS in the pembrolizumab arm compared to chemotherapy, especially in the first six months following randomization, which may violate the proportional hazard assumption—indicating that during the early post-randomization phase, the HR may be higher than the given HR in the publication before becoming lower (which may be lower than the given HR in the publication) in subsequent phases.

Pembrolizumab, an immune drug, enhances the body's natural defenses against tumors. In the practical application of pembrolizumab, a comprehensive evaluation of these clinical predictors will help better direct the treatment of NSCLC individuals, shape clinical decision-making of NSCLC, and assist in the planning of future RCTs, in order to achieve personalized treatment and finally apply the principles of precision medicine. Beyond that, there is a need to continue investigating the potential benefit of pembrolizumab as part of a multi-modal treatment approach for advanced/metastatic NSCLC. In fact, we are beginning an exciting journey for patients and scientific research.

In summary, this meta-analysis revealed that pembrolizumab-based therapy is a valuable option for the treatment of advanced/metastatic NSCLC. Age, sex, smoking history and PD-L1 expression status can be used to predict the clinical benefit of pembrolizumab. Cautious use of pembrolizumab is needed in patients with NSCLC aged ≥ 75 years, females, never smokers, or in patients with TPS 1–49%. Furthermore, pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy may be a more effective treatment option, regardless of the clinical and molecular characteristics of patients with NSCLC. The results of this analysis will contribute to the design of future clinical trials based on predefined subgroups.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21551.

Li Z, Huang J, Shen S, Ding Z, Luo Q, Chen Z, et al. SIRT6 drives epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer via snail-dependent transrepression of KLF4. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):323. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-018-0984-z.

Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, Honjo T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11(11):3887–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x.

Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012.

Giroux Leprieur E, Dumenil C, Julie C, Giraud V, Dumoulin J, Labrune S, et al. Immunotherapy revolutionises non-small-cell lung cancer therapy: Results, perspectives and new challenges. Eur J Cancer. 2017;78:16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.041.

Pai-Scherf L, Blumenthal GM, Li H, Subramaniam S, Mishra-Kalyani PS, He K, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for Treatment of Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: First-Line Therapy and Beyond. Oncologist. 2017;22(11):1392–9. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0078.

Havel JJ, Chowell D, Chan TA. The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(3):133–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0116-x.

Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(5):275–87. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2016.36.

Nishimura H, Nose M, Hiai H, Minato N, Honjo T. Development of lupus-like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD-1 gene encoding an ITIM motif-carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity. 1999;11(2):141–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80089-8.

McDermott DF, Atkins MB. PD-1 as a potential target in cancer therapy. Cancer Med. 2013;2(5):662–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.106.

Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192(7):1027–34. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.192.7.1027.

Latchman Y, Wood CR, Chernova T, Chaudhary D, Borde M, Chernova I, et al. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(3):261–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/85330.

Carter L, Fouser LA, Jussif J, Fitz L, Deng B, Wood CR, et al. PD-1:PD-L inhibitory pathway affects both CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells and is overcome by IL-2. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32(3):634–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3%3c634::AID-IMMU634%3e3.0.CO;2-9.

Chow L, Haddad R, Gupta S, Mahipal A, Mehra R, Tahara M, et al. Antitumor Activity of Pembrolizumab in Biomarker-Unselected Patients With Recurrent and/or Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Results From the Phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 Expansion Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(32):3838–45. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.68.1478.

Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1606774.

Homšek A, Radosavljević D, Miletić N, Spasić J, Jovanović M, Miljković B, et al. Review of the Clinical Pharmacokinetics, Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab. Curr Drug Metab. 2022;23(6):460–72. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200223666220609125013.

Patnaik A, Kang SP, Rasco D, Papadopoulos KP, Elassaiss-Schaap J, Beeram M, et al. Phase I Study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475; Anti-PD-1 Monoclonal Antibody) in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(19):4286–93. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2607.

Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Pérez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1540–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7.

Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078–92. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801005.

Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, Tafreshi A, Gümüş M, Mazières J, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2040–51. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1810865.

Mok T, Wu YL, Kudaba I, Kowalski DM, Cho BC, Turna HZ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1819–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7.

Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Updated Analysis of KEYNOTE-024: Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7):537–46. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.00149.

Gadgeel S, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Speranza G, Esteban E, Felip E, Dómine M, et al. Updated Analysis From KEYNOTE-189: Pembrolizumab or Placebo Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum for Previously Untreated Metastatic Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(14):1505–17. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.03136.

Herbst RS, Garon EB, Kim DW, Cho BC, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Long-Term Outcomes and Retreatment Among Patients With Previously Treated, Programmed Death-Ligand 1-Positive, Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in the KEYNOTE-010 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(14):1580–90. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.02446.

Awad MM, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, Patnaik A, Yang JC, Powell SF, et al. Long-Term Overall Survival From KEYNOTE-021 Cohort G: Pemetrexed and Carboplatin With or Without Pembrolizumab as First-Line Therapy for Advanced Nonsquamous NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(1):162–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2020.09.015.

Hegde PS, Chen DS. Top 10 Challenges in Cancer Immunotherapy. Immunity. 2020;52(1):17–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.12.011.

Munari E, Mariotti FR, Quatrini L, Bertoglio P, Tumino N, Vacca P, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 in Cancer: Pathophysiological, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22105123.

Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park K, Gandara DDR. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X.

Borghaei H, Gettinger S, Vokes EE, Chow L, Burgio MA, de Castro CJ, et al. Five-Year Outcomes From the Randomized, Phase III Trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):723–33. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.01605.

Addeo A, Friedlaender A, Banna GL, Weiss GJ. TMB or not TMB as a biomarker: That is the question. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;163:103374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103374.

Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553(7689):446–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25183.

Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(18):1693–703. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1006448.

Kim ES, Herbst RS, Wistuba II, Lee JJ, Blumenschein GR Jr, Tsao A, et al. The BATTLE trial: personalizing therapy for lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1(1):44–53. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0010.

Okazaki T, Chikuma S, Iwai Y, Fagarasan S, Honjo T. A rheostat for immune responses: the unique properties of PD-1 and their advantages for clinical application. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(12):1212–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.2762.

Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359(6382):1350–5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar4060.

Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2018–28. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1501824.

Sul J, Blumenthal GM, Jiang X, He K, Keegan P, Pazdur R. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Patients With Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Whose Tumors Express Programmed Death-Ligand 1. Oncologist. 2016;21(5):643–50. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0498.

Gadgeel SM, Stevenson JP, Langer CJ, Gandhi L, Borghaei H, Patnaik A, et al. Pembrolizumab and platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Phase 1 cohorts from the KEYNOTE-021 study. Lung Cancer. 2018;125:273–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.08.019.

van Vugt M, Stone JA, De Greef R, Snyder ES, Lipka L, Turner DC, et al. Immunogenicity of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-019-0663-4.

He BX, Zhong YF, Zhu YB, Deng JJ, Fang MJ, She YL, et al. Deep learning for predicting immunotherapeutic efficacy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients: a retrospective study combining progression-free survival risk and overall survival risk. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2022;11(4):670–85. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-22-244.

Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1348.

Rizvi H, Sanchez-Vega F, La K, Chatila W, Jonsson P, Halpenny D, et al. Molecular Determinants of Response to Anti-Programmed Cell Death (PD)-1 and Anti-Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Blockade in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Profiled With Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(7):633–41. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.75.3384.

Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, Creelan B, Horn L, Steins M, et al. First-Line Nivolumab in Stage IV or Recurrent Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25):2415–26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1613493.

Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, Lee JS, Otterson GA, Audigier-Valette C, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2093–104. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801946.

Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJ, Robert L, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515(7528):568–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13954.

Ahamadi M, Freshwater T, Prohn M, Li CH, de Alwis DP, de Greef R, et al. Model-Based Characterization of the Pharmacokinetics of Pembrolizumab: A Humanized Anti-PD-1 Monoclonal Antibody in Advanced Solid Tumors. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6(1):49–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp4.12139.

Chatterjee MS, Elassaiss-Schaap J, Lindauer A, Turner DC, Sostelly A, Freshwater T, et al. Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling of Tumor Size Dynamics in Pembrolizumab-Treated Advanced Melanoma. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6(1):29–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp4.12140.

Li H, Yu J, Liu C, Liu J, Subramaniam S, Zhao H, et al. Time dependent pharmacokinetics of pembrolizumab in patients with solid tumor and its correlation with best overall response. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2017;44(5):403–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10928-017-9528-y.

Li H, Sun Y, Yu J, Liu C, Liu J, Wang Y. Semimechanistically Based Modeling of Pembrolizumab Time-Varying Clearance Using 4 Longitudinal Covariates in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Pharm Sci. 2019;108(1):692–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xphs.2018.10.064.

Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A. Phytochemicals inhibit the immunosuppressive functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC): Impact on cancer and age-related chronic inflammatory disorders. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;61:231–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2018.06.005.

Yusup A, Wang HJ, Rahmutula A, Sayim P, Zhao ZL, Zhang GQ. Clinical features and prognosis in colorectal cancer patients with different ethnicities in Northwest China. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(41):7183–8. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i41.7183.

Quinn BA, Deng X, Colton A, Bandyopadhyay D, Carter JS, Fields EC. Increasing age predicts poor cervical cancer prognosis with subsequent effect on treatment and overall survival. Brachytherapy. 2019;18(1):29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brachy.2018.08.016.

Elias R, Karantanos T, Sira E, Hartshorn KL. Immunotherapy comes of age: Immune aging & checkpoint inhibitors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8(3):229–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2017.02.001.

Ferrara R, Mezquita L, Auclin E, Chaput N, Besse B. Immunosenescence and immunecheckpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer patients: Does age really matter. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;60:60–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.08.003.

Van Beek AA, Hoogerland JA, Belzer C, De Vos P, De Vos WM, Savelkoul HF, et al. Interaction of mouse splenocytes and macrophages with bacterial strains in vitro: the effect of age in the immune response. Benef Microbes. 2016;7(2):275–87. https://doi.org/10.3920/BM2015.0094.

Yi X, Yuan Y, Li N, Yi L, Wang C, Qi Y, et al. A mouse model with age-dependent immune response and immune-tolerance for HBV infection. Vaccine. 2018;36(6):794–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.071.

Eichinger KM, Resetar E, Orend J, Anderson K, Empey KM. Age predicts cytokine kinetics and innate immune cell activation following intranasal delivery of IFNγ and GM-CSF in a mouse model of RSV infection. Cytokine. 2017;97:25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2017.05.019.

Quinn KM, Fox A, Harland KL, Russ BE, Li J, Nguyen T, et al. Age-Related Decline in Primary CD8+ T Cell Responses Is Associated with the Development of Senescence in Virtual Memory CD8+ T Cells. Cell Rep. 2018;23(12):3512–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.057.

Liu R, Zhang S, Ma W, Lu H, Gao J, Gan X, et al. Age-dependent loss of induced regulatory T cell function exacerbates liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol Immunol. 2018;103:251–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2018.10.004.

Dawany N, Parzych EM, Showe LC, Ertl HC. Age-related changes in the gene expression profile of antigen-specific mouse CD8+ T cells can be partially reversed by blockade of the BTLA/CD160 pathways during vaccination. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8(12):3272–97. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.101105.

Xie J, Zhang J, Wu H, Tang X, Liu J, Cheng G, et al. The influences of age on T lymphocyte subsets in C57BL/6 mice. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2017;24(1):108–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.09.002.

Bandaranayake T, Shaw AC. Host Resistance and Immune Aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(3):415–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2016.02.007.

Elias R, Morales J, Rehman Y, Khurshid H. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Older Adults. Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18(8):47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-016-0534-9.

Yang Z, Chen Y, Wang Y, Hu M, Qian F, Zhang Y, et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Monotherapy as a First-Line Treatment in Elderly Patients (≥75 Years Old) With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:807575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.807575.

Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(7):1073–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgp127.

Champiat S, Dercle L, Ammari S, Massard C, Hollebecque A, Postel-Vinay S, et al. Hyperprogressive Disease Is a New Pattern of Progression in Cancer Patients Treated by Anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(8):1920–8. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1741.

Champiat S, Ferrara R, Massard C, Besse B, Marabelle A, Soria JC, et al. Hyperprogressive disease: recognizing a novel pattern to improve patient management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(12):748–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-018-0111-2.

Cook MB, Dawsey SM, Freedman ND, Inskip PD, Wichner SM, Quraishi SM, et al. Sex disparities in cancer incidence by period and age. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(4):1174–82. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1118.

Cook MB, McGlynn KA, Devesa SS, Freedman ND, Anderson WF. Sex disparities in cancer mortality and survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1629–37. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0246.

Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331(6024):1565–70. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1203486.

Conforti F, Pala L, Bagnardi V, De Pas T, Martinetti M, Viale G, et al. Cancer immunotherapy efficacy and patients’ sex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(6):737–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4.

Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Shukla SA, Blank C, Zimmer L, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350(6257):207–11. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad0095.

Gupta S, Artomov M, Goggins W, Daly M, Tsao H. Gender Disparity and Mutation Burden in Metastatic Melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(11). https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv221.

Xiao D, Pan H, Li F, Wu K, Zhang X, He J. Analysis of ultra-deep targeted sequencing reveals mutation burden is associated with gender and clinical outcome in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(16):22857–64. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.8213.

Salem ME, Xiu J, Lenz HJ, Atkins MB, Marshall J. Characterization of tumor mutation load (TML) in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):11517–11517.

Libert C, Dejager L, Pinheiro I. The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(8):594–604. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2815.

Markle JG, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, Robertson CE, Feazel LM, Rolle-Kampczyk U, et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science. 2013;339(6123):1084–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1233521.

Markle JG, Fish EN. SeXX matters in immunity. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(3):97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2013.10.006.

Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.90.

Org E, Mehrabian M, Parks BW, Shipkova P, Liu X, Drake TA, et al. Sex differences and hormonal effects on gut microbiota composition in mice. Gut Microbes. 2016;7(4):313–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1203502.

Lee CK, Man J, Lord S, Links M, Gebski V, Mok T, et al. Checkpoint Inhibitors in Metastatic EGFR-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer-A Meta-Analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(2):403–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.007.

Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Baade PD. The International Epidemiology of Lung Cancer: geographical distribution and secular trends. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(8):819–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818020eb.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, Yatabe Y, Austin J, Beasley MB, et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(9):1243–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630.

Subramanian J, Morgensztern D, Goodgame B, Baggstrom MQ, Gao F, Piccirillo J, et al. Distinctive characteristics of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the young: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(1):23–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c41e8d.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21254.

Janssen-Heijnen ML, Schipper RM, Razenberg PP, Crommelin MA, Coebergh JW. Prevalence of co-morbidity in lung cancer patients and its relationship with treatment: a population-based study. Lung Cancer. 1998;21(2):105–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5002(98)00039-7.

Papi A, Casoni G, Caramori G, Guzzinati I, Boschetto P, Ravenna F, et al. COPD increases the risk of squamous histological subtype in smokers who develop non-small cell lung carcinoma. Thorax. 2004;59(8):679–81. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2003.018291.

Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Templeton PA, Moran CA. Bronchogenic carcinoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1994;14(2):429–46. quiz 447–8. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.14.2.8190965.

Hirsch FR, Spreafico A, Novello S, Wood MD, Simms L, Papotti M. The prognostic and predictive role of histology in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a literature review. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(12):1468–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e318189f551.

Nichols L, Saunders R, Knollmann FD. Causes of death of patients with lung cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(12):1552–7. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2011-0521-OA.

Miyamae Y, Shimizu K, Hirato J, Araki T, Tanaka K, Ogawa H, et al. Significance of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in squamous cell lung carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2011;25(4):921–8. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2011.1182.

Caliò A, Nottegar A, Gilioli E, Bria E, Pilotto S, Peretti U, et al. ALK/EML4 fusion gene may be found in pure squamous carcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(5):729–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0000000000000109.

Pan Y, Wang R, Ye T, Li C, Hu H, Yu Y, et al. Comprehensive analysis of oncogenic mutations in lung squamous cell carcinoma with minor glandular component. Chest. 2014;145(3):473–9. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-2679.

König K, Peifer M, Fassunke J, Ihle MA, Künstlinger H, Heydt C, et al. Implementation of Amplicon Parallel Sequencing Leads to Improvement of Diagnosis and Therapy of Lung Cancer Patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(7):1049–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0000000000000570.

Zhao W, Choi YL, Song JY, Zhu Y, Xu Q, Zhang F, et al. ALK, ROS1 and RET rearrangements in lung squamous cell carcinoma are very rare. Lung Cancer. 2016;94:22–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.01.011.

Masters GA, Temin S, Azzoli CG, Giaccone G, Baker S Jr, Brahmer JR, et al. Systemic Therapy for Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(30):3488–515. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1342.

Novello S, Barlesi F, Califano R, Cufer T, Ekman S, Levra MG, et al. Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v1–1v27. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw326.

Socinski MA, Obasaju C, Gandara D, Hirsch FR, Bonomi P, Bunn P, et al. Clinicopathologic Features of Advanced Squamous NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(9):1411–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2016.05.024.

Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3543–51. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375.

Tan EH, Rolski J, Grodzki T, Schneider CP, Gatzemeier U, Zatloukal P, et al. Global Lung Oncology Branch trial 3 (GLOB3): final results of a randomised multinational phase III study alternating oral and i.v. vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus docetaxel plus cisplatin as first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(7):1249–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn774.

Socinski MA, Bondarenko I, Karaseva NA, Makhson AM, Vynnychenko I, Okamoto I, et al. Weekly nab-paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin versus solvent-based paclitaxel plus carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: final results of a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2055–62. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5848.

Hoang T, Dahlberg SE, Schiller JH, Johnson DH. Does histology predict survival of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with platin-based chemotherapy? An analysis of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E1594. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(1):47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.03.018.

Kelly K, Chansky K, Mack PC, Lara PN Jr, Hirsch FR, Franklin WA, et al. Chemotherapy outcomes by histologic subtypes of non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of the southwest oncology group database for antimicrotubule-platinum therapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14(6):627–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2013.06.010.

Ritzwoller DP, Carroll NM, Delate T, Hornbrook MC, Kushi L, Aiello Bowles EJ, et al. Patterns and predictors of first-line chemotherapy use among adults with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the cancer research network. Lung Cancer. 2012;78(3):245–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.09.008.

Søgaard M, Thomsen RW, Bossen KS, Sørensen HT, Nørgaard M. The impact of comorbidity on cancer survival: a review. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5(Suppl 1):3–29. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S47150.

Tabchi S, Kassouf E, Florescu M, Tehfe M, Blais N. Factors influencing treatment selection and survival in advanced lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(2):e115–115e122. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.24.3355.

Morabito A, Gebbia V, Di Maio M, Cinieri S, Viganò MG, Bianco R, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine and cisplatin vs. gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and a performance status of 2: the CAPPA-2 study. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(1):77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.04.008.

Mörth C, Valachis A. Single-agent versus combination chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and performance status 2: a literature-based meta-analysis of randomized studies. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(3):209–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.03.015.

Strøm HH, Bremnes RM, Sundstrøm SH, Helbekkmo N, Aasebø U. Poor prognosis patients with inoperable locally advanced NSCLC and large tumors benefit from palliative chemoradiotherapy: a subset analysis from a randomized clinical phase III trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(6):825–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0000000000000184.

Caires-Lima R, Cayres K, Protásio B, Caires I, Andrade J, Rocha L, et al. Palliative chemotherapy outcomes in patients with ECOG-PS higher than 1. Ecancermedicalscience. 2018;12:831. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2018.831.

Tan PS, Lopes G, Acharyya S, Bilger M, Haaland B. Bayesian network meta-comparison of maintenance treatments for stage IIIb/IV non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with good performance status not progressing after first-line induction chemotherapy: results by performance status, EGFR mutation, histology and response to previous induction. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(16):2330–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.007.

Socinski MA, Obasaju C, Gandara D, Hirsch FR, Bonomi P, Bunn PA Jr, et al. Current and Emergent Therapy Options for Advanced Squamous Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(2):165–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2017.11.111.

Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Brahmer JR, Juergens RA, Borghaei H, Gettinger S, et al. Nivolumab in Combination With Platinum-Based Doublet Chemotherapy for First-Line Treatment of Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(25):2969–79. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9861.

Peters S, Gettinger S, Johnson ML, Jänne PA, Garassino MC, Christoph D, et al. Phase II Trial of Atezolizumab As First-Line or Subsequent Therapy for Patients With Programmed Death-Ligand 1-Selected Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (BIRCH). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(24):2781–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.71.9476.

Ksienski D, Wai ES, Croteau N, Freeman AT, Chan A, Fiorino L, et al. Pembrolizumab for advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer: Efficacy and safety in everyday clinical practice. Lung Cancer. 2019;133:110–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.05.005.

Condoluci A, Mazzara C, Zoccoli A, Pezzuto A, Tonini G. Impact of smoking on lung cancer treatment effectiveness: a review. Future Oncol. 2016;12(18):2149–61. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2015-0055.

Li B, Huang X, Fu L. Impact of smoking on efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3691–6. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S156421.

Lee CK, Man J, Lord S, Cooper W, Links M, Gebski V, et al. Clinical and Molecular Characteristics Associated With Survival Among Patients Treated With Checkpoint Inhibitors for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(2):210–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4427.

El-Osta H, Jafri S. Predictors for clinical benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 2019;11(3):189–99. https://doi.org/10.2217/imt-2018-0086.

Li X, Huang C, Xie X, Wu Z, Tian X, Wu Y, et al. The impact of smoking status on the progression-free survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving molecularly target therapy or immunotherapy versus chemotherapy: A meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;46(2):256–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.13309.

Kim JH, Kim HS, Kim BJ. Prognostic value of smoking status in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(54):93149–55. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.18703.

Garassino MC, Gelibter AJ, Grossi F, Chiari R, Soto Parra H, Cascinu S, et al. Italian Nivolumab Expanded Access Program in Nonsquamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients: Results in Never-Smokers and EGFR-Mutant Patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(8):1146–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.025.

West H, McCleod M, Hussein M, Morabito A, Rittmeyer A, Conter HJ, et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(7):924–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30167-6.

de Alencar V, Formiga MN, de Lima V. Inherited lung cancer: a review Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1008. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2020.1008.

Wang GZ, Zhang L, Zhao XC, Gao SH, Qu LW, Yu H, et al. The Aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediates tobacco-induced PD-L1 expression and is associated with response to immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1125. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08887-7.

Hu Z, Zheng X, Jiao D, Zhou Y, Sun R, Wang B, et al. LunX-CAR T Cells as a Targeted Therapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;17:361–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2020.04.008.

Qu J, Mei Q, Chen L, Zhou J. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cell therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): current status and future perspectives. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021;70(3):619–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-020-02735-0.

Azevedo CR, Cezana L, Moraes ES, Begnami MD, Paiva Júnior TF, Dettino AL, et al. Synchronous thyroid and colon metastases from epidermoid carcinoma of the lung: case report. Sao Paulo Med J. 2010;128(6):371–4. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1516-31802010000600011.

Gibson A, Li H, D’Silva A, Tudor RA, Elegbede AA, Otsuka SM, et al. Impact of number versus location of metastases on survival in stage IV M1b non-small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2018;35(9):117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-018-1182-8.

Ali A, Goffin JR, Arnold A, Ellis PM. Survival of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer after a diagnosis of brain metastases. Curr Oncol. 2013;20(4):e300–6. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.20.1481.

Ernani V, Stinchcombe TE. Management of Brain Metastases in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(11):563–70. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00357.

Kersten K, Salvagno C, de Visser KE. Exploiting the Immunomodulatory Properties of Chemotherapeutic Drugs to Improve the Success of Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2015;6:516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00516.

Peng J, Hamanishi J, Matsumura N, Abiko K, Murat K, Baba T, et al. Chemotherapy Induces Programmed Cell Death-Ligand 1 Overexpression via the Nuclear Factor-κB to Foster an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75(23):5034–45. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3098.

Wang Z, Till B, Gao Q. Chemotherapeutic agent-mediated elimination of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(7):e1331807. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2017.1331807.

Afzal MZ, Dragnev K, Shirai K. A tertiary care cancer center experience with carboplatin and pemetrexed in combination with pembrolizumab in comparison with carboplatin and pemetrexed alone in non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(6):3575–84. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2018.06.08.

Chen DS, Irving BA, Hodi FS. Molecular pathways: next-generation immunotherapy–inhibiting programmed death-ligand 1 and programmed death-1. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(24):6580–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1362.

Soria JC, Marabelle A, Brahmer JR, Gettinger S. Immune checkpoint modulation for non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(10):2256–62. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2959.

Buchbinder EI, Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathways: Similarities, Differences, and Implications of Their Inhibition. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39(1):98–106. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000239.

Chen YB, Mu CY, Huang JA. Clinical significance of programmed death-1 ligand-1 expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a 5-year-follow-up study. Tumori. 2012;98(6):751–5. https://doi.org/10.1700/1217.13499.

D’Incecco A, Andreozzi M, Ludovini V, Rossi E, Capodanno A, Landi L, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in molecularly selected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(1):95–102. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.555.

Cha YJ, Kim HR, Lee CY, Cho BC, Shim HS. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of programmed cell death ligand-1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma and its relationship with p53 status. Lung Cancer. 2016;97:73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.05.001.

Takada K, Okamoto T, Shoji F, Shimokawa M, Akamine T, Takamori S, et al. Clinical Significance of PD-L1 Protein Expression in Surgically Resected Primary Lung Adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(11):1879–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.006.

Li H, Xu Y, Wan B, Song Y, Zhan P, Hu Y, et al. The clinicopathological and prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression assessed by immunohistochemistry in lung cancer: a meta-analysis of 50 studies with 11,383 patients. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(4):429–49. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr.2019.08.04.

Tuminello S, Sikavi D, Veluswamy R, Gamarra C, Lieberman-Cribbin W, Flores R, et al. PD-L1 as a prognostic biomarker in surgically resectable non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020;9(4):1343–60. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-19-638.

Majem M, Cobo M, Isla D, Marquez-Medina D, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Casal-Rubio J, et al. PD-(L)1 Inhibitors as Monotherapy for the First-Line Treatment of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients with High PD-L1 Expression: A Network Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10071365.

Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(21):2339–49. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.00174.

Rozeman EA, Menzies AM, van Akkooi A, Adhikari C, Bierman C, van de Wiel BA, et al. Identification of the optimal combination dosing schedule of neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma (OpACIN-neo): a multicentre, phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(7):948–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30151-2.

Haanen JB, Blank CU. Prognostic and predictive role of the tumor immune landscape. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;64(2):143–51. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1824-4785.20.03255-0.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the China Anti-Cancer Association HER2 target Chinese Research Fund (CETSDSSCORP239018); and Key Project of Science & Technology Development Fund of Tianjin Education Commission for Higher Education (2022ZD064), China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(I) Conception and design: PC, GWH, and WJL; (II) collection and assembly of data: WJL and GWH; (III) assessment of the eligibility of feasible studies: WJL and GWH; (IV) statistical analysis: WJL and GWH; (V) methodology and visualization: WJL and GWH; (VI) writing of the first draft of the manuscript: WJL and GWH; (VII) revision and editing of the manuscript: WJL and GWH; (VIII) final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article