Abstract

Background

Recurrent esophageal cancer is associated with dismal prognosis. There is no consensus about the role of surgical treatments in patients with limited recurrences. This study aimed to evaluate the role of surgical resection in patients with resectable recurrences after curative esophagectomy and to identify their prognostic factors.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed patients with recurrent esophageal cancer after curative esophagectomy between 2004 and 2017 and included those with oligo-recurrence that was amenable for surgical intent. The prognostic factors of overall survival (OS) and post-recurrence survival (PRS), as well as the survival impact of surgical resection, were analyzed.

Results

Among 654 patients after curative esophagectomies reviewed, 284 (43.4%) had disease recurrences. The recurrences were found resectable in 63 (9.6%) patients, and 30 (4.6%) patients received surgery. The significant prognostic factors of PRS with poor outcome included mediastinum lymph node (LN) recurrence and pathologic T3 stage. In patients with and without surgical resection for recurrence cancer, the 3-year OS rates were 65.6 and 47.6% (p = 0.108), while the 3-year PRS rates were 42.9 and 23.5% (p = 0.100). In the subgroup analysis, surgery for resectable recurrence, compared with non-surgery, could achieve better PRS for patients without any comorbidities (hazard ratio 0.36, 95% CI: 0.14 to 0.94, p = 0.038).

Conclusions

Mediastinum LN recurrence or pathologic T3 was associated with worse OS and PRS in patients with oligo-recurrences after curative esophagectomies. No definite survival benefit was noted in patients undergoing surgery for resectable recurrence, except in those without comorbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Esophageal cancer is an aggressive gastrointestinal cancer with high rates of recurrence even after curative treatments. Although multimodality treatments combining (neo)adjuvant therapy and radical surgical resection have improved the prognosis for esophageal malignancy [1, 2], postoperative recurrence are still associated with dismal prognosis, with a median survival usually no longer than a year [3, 4]. Around 75% of recurrences occurred in the first 2 years after surgery [5]. Patients were empirically given with systemic therapy with palliative-intent or best supportive care according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, whereas only highly selected patients received potentially curative definitive treatment for limited number of metastases [4].

The concept of oligometastases was first proposed by Hellman in 1995 [6]. It is defined as metastases limited in location and number and perhaps represents tumor early in the chain of progression, not been fully developed and with restricted growth. In theory, it is thought to be more indolent in biological nature and clinical behavior, and may be amenable to a curative therapeutic strategy. Niibe et al. [7] proposed the new notion of oligo-recurrence, similar to oligometastases but with controlled primary lesion. In the state of oligo-recurrence, gross recurrent or metastatic sites could be treated using local therapy. As previous studies [8] have shown, patients with oligo-recurrences had better survival than those with multiple recurrences.

Prior studies [8,9,10] have shown that selected patients with oligo-recurrent diseases may benefit from aggressive definitive local therapy compared with systemic management alone. However, there is no consensus about the role of surgical resection in these patients. Our purpose is to analyze the post-recurrence survival in patients with resectable recurrences after curative esophagectomy. We aim to identify the prognostic factors and elucidate the role of surgical resection in the management of resectable oligo-recurrence.

Methods

Study design and eligibility criteria

We retrospectively reviewed patients receiving esophagectomy for cancer at Taipei Veteran General Hospital between January 2004 and December 2017. To identify patients with resectable recurrences after esophagectomy, we excluded the patients who were (1) at M1 stage, (2) operated on R2 resection, (3) lost from follow-up, (4) without evidence of disease recurrence during follow-up period, and (5) with unresectable recurrences.

The preoperative staging examinations in our protocol included physical examination, laboratory tests, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, flexible bronchoscopy (for upper third and middle third tumors), computed tomography (CT) scans from neck to upper abdomen, and radionuclide bone scans. Endoscopic ultrasound and positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) scan became a routine preoperative staging examination for esophageal cancer from 2007. From 2010, multidisciplinary team meetings were held regularly for discussion of examination results and treatment plans. For patients receiving upfront surgery, adjuvant therapy was suggested in patients with pT3/T4 stage and N+ stage. Since the publication of Chemoradiotherapy for Oesophageal Cancer Followed by Surgery Study (CROSS) study, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery has become the popular treatment combination for patients with locally advanced tumors. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital and, because of the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent from included patients was waived (approval no. 2015–06-001 BC).

Follow-up

Clinicopathological stage was determined according to the eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system. After curative treatments, all patients were followed routinely every 3 months in the first 2 years, and every 6–12 months after then. Routine follow-up examinations included serum tumor marker, chest radiography, and CT scan from the neck to the upper abdomen. Endoscopy, abdominal sonogram, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), radionuclide bone scans, and PET/CT scan were obtained as clinically indicated.

Recurrence

Diagnosis of recurrence or metastasis was based on histological, cytological or radiological evidences. Recurrences at the anastomotic site or within the area of previous resection and nodal clearance in the mediastinum or upper abdomen were classified as locoregional recurrence. Distant recurrence was defined as hematogenous metastasis to solid organs or recurrence in the pleura or peritoneal cavity. Resectable lesion was defined as (1) oligo-recurrence, i.e. limited number (≤5) or single site of recurrence, (2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status < 2, and (3) surgical approachability based on image studies and determined by two surgeons, PC Tsai and PK Hsu. For example, recurrence in two solid-organ sites or combined failure (simultaneous locoregional and distant recurrences) was considered as disseminated disease that was unresectable. Patient with limited number of lesions in same lobe of liver but judged as not suitable for partial hepatectomy by a multidisciplinary team meeting was defined as unresectable.

Statistical analyses

Chi-square test was used to compare between categorical variables and independent t test was used to compare between continuous variables. In the survival analysis, overall survival (OS) was defined as the period of time from the curative esophagectomy to death or the last follow-up. Disease free interval (DFI) was defined as the period of time from the curative esophagectomy to the detection of recurrence. The duration between the detection of initial recurrence and either death or the last follow-up was defined as post-recurrence survival (PRS). Survival curves were plotted by Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank test. Cox’s proportional hazards model was used for univariate and multivariate survival analysis. A p < 0.05 was defined as indicative of statistical significance. All calculations were performed using IBM SPSS 25.0 software, and picture design was finished based on R version 4.1.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA) using the Survival, ggplot2, survminer packages.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 654 patients who underwent esophagectomy between 2004 and 2017 were included, and 284 of them (43.4%) had disease recurrence. After exclusionary screening, 63 patients were deemed with oligo-recurrence amenable for surgical intent. Based on definitive treatments for “resectable” recurrences, these patients were divided into operation group (n = 30) and non-operation group (n = 33) (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows their clinical and pathologic features. Both groups of patients were overwhelmingly male (96.8%), and had squamous cell carcinoma (95.2%) as the histologic cell type of esophageal cancer. The patients in non-operation group were older (median age: 60 vs. 52 yrs., p = 0.003), and had more with locoregional oligo-recurrence (31.7% vs. 11.2%, p = 0.003). Otherwise, we found no substantial differences between both groups in parameters such as gender, performance status, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), tumor characteristics, or initial treatment modality of the primary esophageal cancer.

Recurrence pattern and treatment modalities

During the mean follow-up of 38 months, the median period of time to develop recurrence was 13 months. The patterns of recurrences were distant only in 36 (36/63, 57.1%) patients, and locoregional only in 27 (27/63, 42.9%) patients (Table 1). The treatment modalities for resectable recurrences are shown in Table 2. In the operation group, surgical resection followed by chemotherapy (53.3%) was the most common treatment combination. Most (80%) of the patients had additional treatments after surgery, whereas the other 20% had surgery only. In the non-operation group, chemoradiotherapy (42.4%) was the most common treatments, followed by chemotherapy only (27.3%) and local radiotherapy only (12.1%). Specifically in the operation group (among 63 patients having resectable recurrences), one of five patients with anastomosis recurrence underwent revision of esophagogastric anastomosis; 17 of 21 patients with isolated lung metastasis had lung resection. One of four patients with liver oligo-recurrence received lateral hepatectomy and 3 other patients had radiofrequency ablation. One patient with pleural/chest wall oligo-recurrence underwent cryoablation plus radiotherapy.

Factors of PRS and OS

The overall 1- and 3-year PRS rates were 62.7 and 31.6%. Median survival for all patients after recurrence was 18 months (interquartile range (IQR): 8 to 64 months). The prognostic factors of PRS are shown in Table 3. In the multivariate analysis with forward selection criteria, pathologic T3 stage (hazard ratio 2.53, 95% CI: 1.36 to 4.71, p = 0.003) and mediastinum recurrence (hazard ratio 3.81, 95% CI: 1.76 to 8.26, p = 0.006) were the independent prognostic factors of PRS.

In the univariate analysis (Table 4), pathologic T3 stage, DFI less than 12 months, brain metastasis, and mediastinal recurrence demonstrated to be significant factors of OS. Similar to the findings of PRS, pathologic T3 stage (hazard ratio 3.17, 95% CI: 1.57 to 6.37, p = 0.001) and mediastinum recurrence (hazard ratio 4.21, 95% CI: 1.88 to 9.43, p = 0.001) were also the poor prognostic factors of OS. Additionally, we found brain metastasis (hazard ratio 8.21, 95% CI: 2.19 to 30.78, p = 0.002) as an independent prognostic factor of worse OS.

Impact of treatment modality on survival

Figure 2 demonstrates the impact curves of different treatment modalities on patient outcome (A: PRS; B: OS). Patients were divided into surgery (surgical resection +/− systemic therapy), local therapy (radiation therapy/radiofrequency ablation/cryoablation +/− systemic therapy), chemotherapy only, and palliative care groups. Although the patients who underwent surgery seemed to have better outcomes--median OS: 42.5 months, interquartile range (IQR):20.3–64.8; and median PRS: 18 months, no statistical significance was reached. There was no significant difference between surgery and non-surgery groups (median OS: 35 months (IQR:16.5–56.5); median PRS: 13 months; p = 0.108 in PRS and p = 0.100 in OS), and between any types of local treatments and systemic treatments (median OS: 39.5 months (IQR:19–60.8) vs. 23 (IQR:13–51), p = 0.171; median PRS: 16.5 vs 8 months, p = 0.145). Further subgroup analysis of patient who underwent surgery (with adjuvant therapy or not) or alternative treatment (chemo-radiotherapy/chemotherapy only/ radiotherapy only) were demonstrated in Fig. 3, with limited sample size in some groups. No significant difference between surgery alone and surgery with adjuvant therapy groups (median OS: 41 (IQR:22.8–57) vs. 42.5 months (IQR:22.8–59.5), p = 0.284; median PRS: 17.5 (IQR:9–25.3) vs 18 months (IQR:9–29), p = 0.497). Between chemo-radiotherapy /chemotherapy only/ radiotherapy only treatment groups (median OS: 45.5 vs. 31 vs 31 months; median PRS: 13 vs 15.5 vs 17 months, respectively) were no statistical significance in each group comparison.

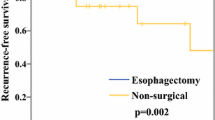

To identify who might benefit from surgical resection for resectable recurrence, survival analysis was undertaken to compare between operation and non-operation groups (Fig. 4). Although operation, in general, led to better outcomes, CCI = 0 was identified as the only indicator to make significant difference between operation and non-operation. Patients without comorbidities could expect significantly better PRS outcome from surgery for resectable recurrence than from non-operation treatments (hazard ratio 0.36, 95% CI: 0.14 to 0.94, p = 0.038).

Discussion

Esophageal cancer is one of the deadliest cancers with rapidly rising incidence. In our previous report [3], tumor recurrence after curative esophagectomy developed in 42.9% of patients in the median of only 10 months. As high as 66.2% of recurrences happened within 1 year after operation. The reported prognostic factors of PRS included liver recurrence, shorter disease-free interval and palliative therapy. Distant recurrence and more than 3 recurrent locations were associated with worse PRS, as demonstrated in K. Parry et al’s study [4]. In current study on patients with oligo-recurrence after esophagectomy, we identified pathological T3 stage and mediastinal recurrence as the prognostic factors of PRS.

In general, patients with multiple recurrent sites had a worse survival compared with those with less involved sites [8]. Combined failure pattern of simultaneous locoregional and distant recurrences also had inferior outcome [9]. Indeed, patients with recurrent esophageal disease deserved multimodality therapy for better outcome. Furthermore, based on the rising publications showing evidence that oligo-recurrence may represent tumors with more favorable biology, early identification and aggressive treatment for oligometastatic recurrence might improve survival [8,9,10,11,12]. However, the role of surgery in patients with isolated oligo-recurrence has not yet been defined.

In Ghaly et al’s study [11], no pronounced difference was found in disease-free survival or in PRS between patients with oligo-recurrence treated with operation, with or without chemo- and radiotherapy, and patients who received definitive chemoradiotherapy without resection. In contrast, the study by Depypere et al. [9] demonstrated prolonged survival in patients with isolated locoregional recurrence or single solid organ metastasis, especially if surgery was offered. Surgical resection (+/− systemic therapy) of solitary recurrent lesion was a considerable therapeutic option for well-selected patients with recurrent esophageal carcinoma. Similarily, Ohkura et al. [8] reported a significantly better OS rate in the patients who underwent resection of oligo-recurrences than in those who did not. However, they found no significant difference in survival between the patients with shorter and longer DFI (< 12 months vs. > 12 months), indicating that a shorter DFI should not be an unfavorable prognostic factor to hinder surgeons from choosing surgical resection. In line with these reports, we observed that surgical resection for oligo-recurrence may lead to better OS and PRS, albeit without statistical significance. Most of our patient (95.2%) histologically were classified as squamous cell carcinoma, which has been well demonstrated more chemo-radiosensitive and better pathologic response than adenocarcinoma [2], may have influenced our analysis. However, in subgroup analysis, we found that surgery, compared with non-surgical treatments, may confer survival benefit to patients without comorbidities, highlighting the importance of patient selection in deciding treatment modalities. The cause of death after recurrence might be multi-faceted and complex, patients without comorbidities may well tolerate both surgery and subsequent therapy side effect side-effects without fatal toxicity in our study.

Cervical and mediastinal lymph node failures have been reported to be one of the most common types of recurrence after esophagectomy in patients with thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [3, 13]. In Ni’s study [13], lymph node recurrence above the diaphragm and single region lymph node recurrence exhibited better OS than those at the subphrenic region and multiple regions, respectively. They also identified original pathological stage and salvage treatment regimen as independent prognostic factors. Whereas chemoradiotherapy could offer a safe and effective treatment for patients with lymph node recurrences, especially with a single region failure [14, 15], many reports suggested that salvage cervical lymphadenectomy as the main treatment could achieve locoregional disease control and prolong survival in patients with cervical lymph node (LN) recurrence after curative esophagectomy [16]. Focusing on lymph node recurrence, Nakamura et al. have shown significantly better survival in the lymphadenectomy and chemoradiotherapy groups than in the patients who received chemotherapy or best supportive care for lymph node recurrence after curative esophagectomy [17]. However, there was no statistically significant difference in survival between the surgical lymphadenectomy and chemoradiotherapy groups. Of note, 11 of 12 patients with cervical lymph node recurrence received surgical resection, whereas less than one third of patients with paraesophageal or paratracheal lymph node recurrences had surgical resection. These results were compatible with our findings that only one of 11 patients with isolated mediastinal lymph node recurrence received surgery. Mediastinal lymph node recurrence was also a significant prognostic factor of both OS and PRS. Therefore, the possibility and benefit of salvage surgical resection for mediastinal LN recurrence remains unclear and needs more data to clarify.

Limited reports on oligo-recurrence to distant solid organ have made it difficult to collect sufficient cases for analysis. The role of surgery in these patients thus remains unknown. For example, only 30% of the patients with oligo-recurrence had surgery in Nobel’s study [12]. However, several reports have recommended pulmonary metastasectomy as an acceptable and effective treatment for solitary pulmonary metastasis [18,19,20,21]. For example, Kobayashi et al. analyzed 23 patients who underwent 30 curative pulmonary metastasectomies at a single institution [18]. In their report, the unfavorable prognostic factors included history of extrapulmonary metastases before pulmonary metastasectomy, poorly differentiated primary esophageal carcinoma, and short disease-free interval. Their results also recommended that pulmonary resection for lung metastases from esophageal carcinoma should be considered in carefully selected patients, and repeated metastasectomy was encouraged in suitable patients.

On the other hand, Nobel et al. have reported significantly worse outcome in patients with liver and brain oligo-recurrence from esophageal cancer when compared with lung oligo-recurrence, which showed a more indolent course [12]. In our series, 17 of 21 patients had received pulmonary resection but showed no significant differences in survival analysis compared with patients with oligo-recurrences in other sites. On the contrary, patients with brain oligo-recurrence had worst OS (HR: 3.83, p = 0.031) compared with patients with oligo-recurrences in other sites, which are compatible with the findings in Nobel’s cohort. Whether patients with esophageal cancer should be screened or surveyed for brain metastases remains unclear [22,23,24]. Although a previous study [22] has reported that half of brain oligo-recurrences occurred within 12 months of esophagectomy and all were diagnosed because of symptomatic disease, which led to the suggestion of brain surveillance imaging for high risk patients, there was report showing low incidence of brain metastasis in patients with esophageal carcinoma, which made it unnecessary for baseline screening or surveillance, even the prognosis was poor [23].

There are several limitations in our study. First, this is a single-institution study. The inherent bias of retrospective nature and relatively small sample size may limit the power of statistical significance. Second, due to the lack of strict definition for “resectable” and guidelines for therapeutic approach in each recurrence site, selection bias for treatment modalities and surgical intervention are inevitable. Third, routine surveillance for bone and brain was not performed in our practice, which might miss early diagnosis of oligo-recurrences in these sites. Finally, since only patients with single site of recurrence were selected, the role of surgery in combination with other aggressive local control or systemic therapy in patients with limited or multiple sites of recurrence was beyond the scope of our study. External validation study with more cases is needed to confirm our observations.

Conclusions

Patients with oligo-recurrence represent a small subgroup of patients with recurrence, surgical resection may offer a survival benefit for properly selected patients. We demonstrated that patients with mediastinum LN recurrence or pathologic T3/4 stage were independent factors of OS and PRS for those who had oligo-recurrences after esophagectomy. In patients without comorbidities (CCI = 0), surgical resection was associated with better PRS. Further studies are warranted to define the role of surgical resection in the management of resectable oligo-recurrence.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and IRB approval.

Abbreviations

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PRS:

-

Post-recurrence survival

- DFI:

-

Disease free interval

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CROSS:

-

Chemoradiotherapy for Oesophageal Cancer Followed by Surgery Study

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- EGJ:

-

Esophagogastric junction

- LVI:

-

Lymphovascular invasion

- PNI:

-

Perineural invasion

- TRG:

-

Tumor regression grade

- CRM:

-

Circumferential resection margin

- LN:

-

Lymph node

References

Ando N, Iizuka T, Ide H, et al. Surgery plus chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for localized squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus: a Japan clinical oncology group study—JCOG9204. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(24):4592–6.

van Hagen P, Hulshof MCCM, van Lanschot JJB, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2074–84.

Hsu PK, Wang BY, Huang CS, et al. Prognostic factors for post-recurrence survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients with recurrence after resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(4):558–65.

Parry K, Visser E, van Rossum PS, et al. Prognosis and Treatment After Diagnosis of Recurrent Esophageal Carcinoma Following Esophagectomy with Curative Intent. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(Suppl 3):S1292–300.

Lou F, Sima CS, Adusumilli PS, et al. Esophageal cancer recurrence patterns and implications for surveillance. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(12):1558–62.

Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR. Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):8–10.

Niibe Y, Hayakawa K. Oligometastases and oligo-recurrence: the new era of cancer therapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40(2):107–11.

Ohkura Y, Shindoh J, Ueno M, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of oligometastases from esophageal cancer and long-term outcomes of resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(3):651–9.

Depypere L, Lerut T, Moons J, et al. Isolated local recurrence or solitary solid organ metastasis after esophagectomy for cancer is not the end of the road. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(1):1–8.

Schizas D, Lazaridis II, Moris D, et al. The role of surgical treatment in isolated organ recurrence of esophageal cancer-a systematic review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16(1):55.

Ghaly G, Harrison S, Kamel MK, et al. Predictors of survival after treatment of oligometastases after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(2):357–62.

Nobel TB, Sihag S, Xing XX, et al. Oligometastases after curative esophagectomy are not one-size-fits-all. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;112:1775–81.

Ni W, Yang J, Deng W, et al. Patterns of recurrence after surgery and efficacy of salvage therapy after recurrence in patients with thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):144.

Kawamoto T, Nihei K, Sasai K, et al. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors of chemoradiotherapy for postoperative lymph node recurrence of esophageal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48(3):259–64.

Yamashita H, Jingu K, Niibe Y, et al. Definitive salvage radiation therapy and chemoradiation therapy for lymph node oligo-recurrence of esophageal cancer: a Japanese multi-institutional study of 237 patients. Radiat Oncol. 2017;12(1):38.

Yuan X, Lv J, Dong H, et al. Does cervical lymph node recurrence after oesophagectomy or definitive chemoradiotherapy for thoracic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma benefit from salvage treatment? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2017;24(5):792–5.

Nakamura T, Ota M, Narumiya K, et al. Multimodal treatment for lymph node recurrence of esophageal carcinoma after curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2451–7.

Kobayashi N, Kohno T, Haruta S, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy secondary to esophageal carcinoma: long-term survival and prognostic factors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(Suppl 3):S365–9.

Shiono S, Kawamura M, Sato T, et al. Disease-free interval length correlates to prognosis of patients who underwent metastasectomy for esophageal lung metastases. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(9):1046–9.

Ichikawa H, Kosugi S, Nakagawa S, et al. Operative treatment for metachronous pulmonary metastasis from esophageal carcinoma. Surgery. 2011;149(2):164–70.

Takemura M, Sakurai K, Takii M, et al. Metachronous pulmonary metastasis after radical esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: prognosis and outcome. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;7:103.

Nobel TB, Dave N, Eljalby M, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Isolated Esophageal Cancer Recurrence to the Brain. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109(2):329–36.

Wadhwa R, Taketa T, Correa AM, et al. Incidence of brain metastases after trimodality therapy in patients with esophageal or gastroesophageal cancer: implications for screening and surveillance. Oncology. 2013;85(4):204–7.

Kothari N, Mellon E, Hoffe SE, et al. Outcomes in patients with brain metastasis from esophageal carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7(4):562–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Taipei Veterans General Hospital Esophageal Cancer Panel Members, including Chun-Ku Chen in Department of Radiology; Ko-Han Lin in Department of Nuclear Medicine; Teh-Ying Chou, Yi-Chen Yeh in Department of Pathology; Chueh Chuan Yen, Ming-Huang Chen, Sheng-Yu Chen, Pin-I Huang, Yi-Wei Chen in Department of Oncology, for reviewing patient’s examination results and arranging patient’s treatments and follow-up.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TPC: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing—original draft. CHC: Data acquisition and Analysis. HPK: Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing—review & editing. HJJ: Conceptualization; Supervision. HCC: Conceptualization; Supervision. HWH: Conceptualization; Supervision. HHS: Conceptualization; Supervision. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital and, because of the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent from included patients was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (approval no. 2015–06-001 BC). The study was carried out in accordance to institutional guidelines which is established based on the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, PC., Chien, HC., Hsu, PK. et al. Post-recurrence survival analysis in patients with oligo-recurrence after curative esophagectomy. BMC Cancer 22, 637 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09739-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09739-2