Abstract

Background

High-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) is used in the treatment of different childhood cancers, including leukemia, the most common cancer type and is commonly defined as an intravenous dose of at least 1 g/m2 body surface area per application. A systematic review on late effects on different organs due to HD-MTX is lacking.

Method

We conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed, including studies published in English or German between 1985 and 2020. The population of each study had to consist of at least 75% childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) who had completed the cancer treatment at least twelve months before late effects were assessed and who had received HD-MTX. The literature search was not restricted to specific cancer diagnosis or organ systems at risk for late effects. We excluded case reports, case series, commentaries, editorial letters, poster abstracts, narrative reviews and studies only reporting prevalence of late effects. We followed PRISMA guidelines, assessed the quality of the eligible studies according to GRADE criteria and registered the protocol on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42020212262).

Results

We included 15 out of 1731 identified studies. Most studies included CCSs diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n = 12). The included studies investigated late effects of HD-MTX on central nervous system (n = 10), renal (n = 2) and bone health (n = 3). Nine studies showed adverse outcomes in neuropsychological testing in exposed compared to non-exposed CCSs, healthy controls or reference values. No study revealed lower bone density or worse renal function in exposed CCSs. As a limitation, the overall quality of the studies per organ system was low to very low, mainly due to selection bias, missing adjustment for important confounders and low precision.

Conclusions

CCSs treated with HD-MTX might benefit from neuropsychological testing, to intervene early in case of abnormal results. Methodological shortcomings and heterogeneity of the tests used made it impossible to determine the most appropriate test. Based on the few studies on renal function and bone health, regular screening for dysfunction seems not to be justified. Only screening for neurocognitive late effects is warranted in CCSs treated with HD-MTX.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Improvements in diagnosis and treatment of children with cancer have resulted in high survival rates and a growing population of childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) [1, 2]. Amongst other factors, this high survival rate is achieved through intensive treatments, which can cause late effects in potentially every organ system [3, 4].The early detection and treatment of late effects have become a focus of research. Concomitantly, different national long-term follow-up (LTFU) care guidelines have been established to address the need to detect late effects early, recommend treatment and improve the quality of life of CCS. These LTFU care guidelines include those from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) in the US [5], the United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group Late Effects Group (UKCCLG) [6] and the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG) [7]. These guidelines recommend screening for neurocognitive function, bone mineral density, kidney and liver function in exposed CCSs, but the recommendations are not uniform (Supplemental S1).

HD-MTX has proven to be successful in the treatment of a variety of childhood cancers, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), non-Hodgkin lymphoma, osteosarcoma and certain high-grade tumours of the central nervous system (CNS) [8,9,10,11]. There is no official cut-off dose to define HD-MTX. Ackland et al. defined MTX doses of at least 1 g per body surface area (≥ 1 g/m2) given intravenously as high-dose, as from this dose onwards leucovorin rescue is needed [12]. As clinical guidelines use the same cut-off dose, we used it for this systematic review[13]. Despite the successful use of HD-MTX, no systematic review exists of its potential to cause late effects. This systematic review aims to close this gap and to systematically search for evidence of late effects associated with HD-MTX treatment.

Methods

Literature search

We conducted the systematic literature search in PubMed in June 2020, using the terms “cancer” with different types of cancers written out, “children and adolescents” and “high-dose methotrexate”, including also synonyms and combinations (Supplemental S2). The Cochrane Library search with the term “high-dose methotrexate” resulted in three publications, two on non-oncological diseases and one on primary central nervous system lymphoma in adults. We additionally screened the references in the LTFU care guidelines mentioned for HD-MTX and added studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria, which were not covered by the systematic search. Organs at risk, based on LTFU care guidelines, are the CNS, kidney, bone and liver. We performed this systematic review according to the guidelines of the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis” (PRISMA) [14] and registered the study protocol on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42020212262) [15].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We searched for studies published in English or German between January 1985 and June 2020. Studies before 1985 were excluded as relevant treatment protocols were introduced thereafter and their focus was mainly on survival, not late effects. We defined the following inclusion criteria based on the PICO criteria: (P) study populations with ≥ 75% CCSs, defined as children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer < 19 years of age and the cancer treatment had to be completed at ≥ 12 months before late effects were assessed; (I) the cancer treatment had to contain HD-MTX, (≥ 1 g/m2 per application); (C) the analysis had to include either a comparison between CCSs exposed and not exposed to HD-MTX, comparison to a reference population or a regression analysis investigating the association of a certain late effects with the HD-MTX dose; (O) the outcome was not restricted on specific cancer diagnosis or organ systems at risk for late effects. We excluded case reports, case series (patient number < 10), commentaries, editorial letters, poster abstracts, narrative reviews and studies only reporting prevalence of late effects in a cohort of CCSs exposed to HD-MTX. We additionally excluded studies comparing CCSs treated with HD-MTX to CCSs treated with cranial radiotherapy with or without HD-MTX and studies reporting radiological changes in the brain as primary outcomes.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers (ED and KS) screened all titles and abstracts independently according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, followed by screening the retrieved full texts for eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (MO). Data were extracted by one reviewer (ED), using a standardized data extraction form and were checked by a second reviewer (MO). The corresponding authors of seven studies were contacted to resolve uncertainties related to the data. Five authors responded and three of these studies could be included. We extracted the following information from eligible studies: (a) study details (first author, year of publication, country, study design, statistics); (b) study population (number of participants, sex, year of diagnosis or treatment, age at diagnosis, cancer type); (c) treatment characteristics (treatment protocol, HD-MTX dose per application); (d) outcome measures (method used to assess organ function, reference values, follow-up). We categorized children and adolescents receiving HD-MTX as “HD-MTX” and those without as “No HD-MTX”. If the control groups were healthy children, children diagnosed with cancer before start of treatment or patients without HD-MTX, we extracted information on their age. If any of the information was missing, we indicated this with "N/A".

Two reviewers (ED and MO) assessed the risk of bias of each eligible study independently, including attrition bias, confounding, detection bias and selection bias. A third reviewer (KS) was consulted in case of disagreement. Based on the risk of bias, an overall assessment of the available evidence was performed for each organ system ranging from very low to high quality of evidence based on the adapted GRADE criteria, used by the International Guideline Harmonization Group [16, 17].

Results were finally summarized by identified organ system at risk for late effects and synthesized descriptively.

Results

Literature search

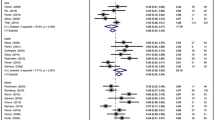

Through the systematic literature search, the manual search of the LTFU care guidelines and after removing duplicates, we identified 1731 studies and subsequently excluded 1668 studies after title and abstract screening. Additional 48 studies were excluded after full-text screening, mainly because the MTX dose was less than 1 g/m2 or the time between exposure and assessment of late affects was less than 12 months. Finally, we included 15 studies (Fig. 1) [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Ten studies assessed neurocognitive function [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], two kidney function [28, 29] and three bone health [30,31,32].

Study populations and control groups

The size of the study populations varied between 21 and 1122 CCSs. All studies on bone health (n = 3) and most on neurocognitive function (n = 9) included CCSs diagnosed with ALL only [18,19,20,21,22, 24,25,26,27]. Both studies assessing renal function included different paediatric cancer types [28, 29]. The comparison groups differed between studies and consisted of childhood cancer patients with outcome assessment before start of treatment [18, 22], childhood cancer patients treated with non-HD-MTX [19,20,21, 31], childhood cancer patients treated with different doses of HD-MTX [27,28,29], healthy controls [23, 26] and reference values [21, 23,24,25, 27, 30, 32]. Follow-up time started in most studies at completion of treatment. The average follow-up time was below 10 years in most studies except for one study on neurocognitive function with a median follow-up of 24.7 years and one study on kidney function with a median follow-up of 15.3 years.

Neurocognitive function

Ten studies examined the effects of HD-MTX on neurocognitive function with results from neuropsychological testing as the primary outcome [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] (Table 1). In all except one study [20] at least one neuropsychological test was significantly worse in CCSs treated with HD-MTX compared to the control. Different tests were carried out to assess neurocognitive function, due to different functional domains. In addition, different versions exist for some tests, such as child-, adult- and abbreviated versions of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale. This made an overall conclusion difficult. However, CCSs treated with HD-MTX performed significantly worse in at least one subtest on processing speed alone [18, 23,24,25]. In all studies investigating memory [23, 25] and visual-motor and fine-motor function [26], exposed CCSs performed worse than controls. In most studies on sustained attention (3 out of 4) at least one subscale was significantly lower in exposed CCSs [23,24,25, 27]. The same was true for memory and attention (2 out of 3 studies) [18, 21, 23], intelligence (IQ) assessment (4 out of 8 studies) [18,19,20,21,22,23, 25, 27], executive function (3 out of 6 studies) [18, 22,23,24,25,26], academic achievement (1 out of 3 studies) [21, 23, 27], and memory and learning (1 out of 2 studies) [22, 26]. In three neurocognitive domains, CCSs treated with HD-MTX did not perform significantly worse in any of the sub-tests than controls: attention and processing speed combined [22, 26], emotional assessment [23], and verbal learning [27] (Supplemental S3).

Kidney function

Two studies investigated kidney function in CCSs treated with HD-MTX. Mulder et al. used the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as primary outcome [29], whereas Grönroos et al. used low-molecular weight proteinuria, albuminuria and GFR measured by isotope method [28]. All CCSs from both studies received MTX-containing treatment, but in different doses. Both studies showed no increased risk for kidney function impairment after higher cumulative doses of HD-MTX [28, 29]. Mulder et al. additionally showed no significant effect of HD-MTX on deterioration of GFR over time in their multivariable logistic regression model [29] (Table 2, Supplemental S4).

Bone health

Three studies examined late effects of HD-MTX on bone health [30,31,32]. Bone mineral density (BMD) was assessed by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Table 3, Supplemental S5). CCSs treated with HD-MTX did not have significantly lower BMD than expected or than CCSs not treated with HD-MTX.

Quality assessment

The overall quality of the evidence was low to very low for the three organ systems (Supplemental S3-S5). Following reasons led to the down-grading of the quality: selection bias, missing adjustment for important confounders and low precision, such as reporting of results as p-values only and without effect size.

Discussion

For three organ systems, we found literature assessing the potential impact of HD-MTX on the development of late effects in CCSs: neurocognition, kidney, and bone. Based on the available literature, exposed CCSs had more often abnormal neurocognitive test results than controls but did not more frequently suffer from impaired kidney function or bone health.

For neurocognitive testing, we found evidence in most included studies (9 out of 10), that CCSs treated with HD-MTX had more frequent abnormal test results or significantly lower scores in at least one subscale compared to controls. This is congruent with the LTFU care guidelines, where all three guidelines recommend testing, either specifically for CCSs treated with HD-MTX or because it is recommended for all CCSs. Our findings are in line with a publication by Cheung et al., assessing 190 CCSs treated for ALL with chemotherapy only [33]. Even though they did not investigate MTX specifically, survivors demonstrated more neurocognitive problems in the domains of working memory, organization, initiation and planning. The pathomechanism of HD-MTX-related neurotoxicity may include alterations in intracellular metabolic pathways due to MTX-induced folate deficiency which may lead to demyelination and elevated levels of homocysteine, which can further be metabolized to excitatory neurotransmitters, causing neurotoxicity [34,35,36]. All but one study on neurocognitive outcomes included only CCSs treated for ALL. Intrathecal MTX is part of the standard treatment for ALL. Therefore, all patients exposed to intrathecal MTX are also exposed to HD-MTX and the potential effect of intrathecal MTX on neurocognitive function is impossible to disentangle in this setting. The only study on non-ALL survivors included 80 osteosarcoma survivors. They did not receive intrathecal MTX and performed significantly worse than the matched controls.

For kidney function, our review shows, that HD-MTX does not have a significantly negative impact in the long-term [28, 29]. This is reflected in the LFTU care guidelines, where it is recommended in one guideline only (Supplemental S1). It is unclear how HD-MTX contributes to kidney function impairment years following completion of treatment. For acute nephrotoxicity the mechanism includes precipitation of MTX and its metabolites within the renal tubules [37]. The methods used to assess kidney function were urinalysis, radioisotop GFR and calculation of GFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula for adults. Urinalysis and estimated GFR (eGFR) based on serum creatinine level are widely used in daily practice. Although the eGFR is standardized for age, sex and ethnic origin, it might under- or overestimate the true GFR, as the creatinine is influenced by the muscle mass. This is the case, if a patients muscle mass deviates from the mean of the reference population of the same sex and age [38]. Cystatin C varies less with anthropometric data. It has been shown that cystatin C-based GFR formulas can provide an accurate estimation of GFR in the paediatric population, including oncology patients [39, 40]. We therefore suggest using cystatin C or cystatin C-based GFR alone or in addition to the eGFR to estimate kidney function in CCSs.

Bone mineral density in CCSs treated with HD-MTX does not significantly differ from the reference values. This contrasts with some LTFU care guidelines, where it either is recommended or not specified (Supplemental S1). This finding is also unexpected, as all three studies included ALL survivors only. Survivors treated for ALL are exposed to high-dose steroids, which are associated with a reduction in BMD [41]. HD-MTX may cause reduced bone mass by several mechanisms, including growth plate dysfunction, damage to osteoprogenitor cells resulting in suppressed bone formation, and increase bone resorption [42]. Our results might be explained by the small cohorts and the missing information on physical activity, nutrition intake and other hormonal deficits in the included studies, which are relevant determinants for BMD [31, 43].

Strengths and limitations

This is the first review summarizing late effects of HD-MTX treatment on different organ systems in CCSs. The key strengths of this study are the thorough application of the systematic review methodology, including the performance of all steps by two reviewers, and the quality assessment of the included studies. The neurocognitive domains assessed, the tests used for each domain and the reference values differed between studies; for example in the Wechsler test [19,20,21]. This made the direct comparison of results from the different studies difficult. Most recently, guidelines and position statements on screening strategies and neurocognitive testing have been published [44, 45]. Similar guidelines would be helpful to assess kidney and bone health in a standardized way. Because of the small numbers of eligible studies and their small population sizes, the results on kidney and bone health might not be representative for all CCSs exposed to HD-MTX. Furthermore, important confounders were not considered, for example socioeconomic status in neuropsychological testing or physical activity for bone health. In addition, the overall quality of the evidence was low to very low.

Conclusion

CCSs treated with HD-MTX are at risk for neurocognitive impairment, but not for significantly worse kidney function or bone health than controls. These findings are in contrast to the currently used LTFU care guidelines, where also kidney, bone, and liver are defined as organs at risk. Further research is needed to fully understand the impact of HD-MTX on late effects in CCSs and its relevance for long-term follow-up care.

Availability of data and materials

The search strategy is available in the supplemental material as additional material.

Abbreviations

- ALL:

-

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- BMD:

-

Bone Mineral Density

- CCS:

-

Childhood Cancer Survivor

- CKD-EPI:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- CNS:

-

Central Nervous System

- COG:

-

Children’s Oncology Group

- DXA:

-

Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry

- DCOG:

-

Dutch Childhood Oncology Group

- eGFR:

-

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

- GFR:

-

Glomerular Filtration Rate

- HD-MTX:

-

High-dose Methotrexate

- LTFU:

-

Long-term follow-up

- MTX:

-

Methotrexate

- UKCCLG:

-

United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group Late Effects Group

References

Winther JF, Kenborg L, Byrne J, Hjorth L, Kaatsch P, Kremer LC, et al. Childhood cancer survivor cohorts in Europe. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden). 2015;54(5):655–68. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186x.2015.1008648.

Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, Aareleid T, Bielska-Lasota M, Clavel J, et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007: results of EUROCARE-5–a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70548-5.

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa060185.

Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, van den Bos C, van der Pal HJ, Heinen RC, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2705–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.24.2705.

Childrens Oncology Group. Long Term Follow-Up guidelines Version 5.0. 2018. (http://www.survivorshipguidelines.orgAccessed 25.08.2020 (October 2018)).

United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group. Therapy based long term follow-up - Practice Statement. 2005.

SKION DCOG. Guidelines for follow-up in survivors of childhood cancer 5 years after diagnosis. 2010. (https://www.skion.nl/voor-patienten-en-ouders/late-effecten/533/richtlijn-follow-up-na-kinderkanker/ Accessed 25.08.2020).

Cooper SL, Brown PA. Treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62(1):61–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2014.09.006.

Mueller S, Chang S. Pediatric brain tumors: current treatment strategies and future therapeutic approaches. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2009;6(3):570–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurt.2009.04.006.

Gross TG, Termuhlen AM. Pediatric non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9(6):459–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-007-0064-6.

Isakoff MS, Bielack SS, Meltzer P, Gorlick R. Osteosarcoma: Current Treatment and a Collaborative Pathway to Success. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(27):3029–35. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.59.4895.

Ackland SP, Schilsky RL. High-dose methotrexate: a critical reappraisal. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1987;5(12):2017–31. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1987.5.12.2017.

Hall GW, S. Guidelines for use of HIGH DOSE METHOTREXATE (HDMTX). NHS. 2017. http://tvscn.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Cancer-Children-High-Dose-Methotrexate-Guidance-for-Haematolgy-and-Oncology-v2.1-Dec-2015.pdf. Accessed 20.11.2021 2021.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2021;88: 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906.

Scheinemann K, E; Otth, M; Drozdov, D; Bargetzi M. Late effect of high-dose methotrexate treatment in childhood cancer survivors - a systematic review. 2020. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020212262.

Kremer LC, Mulder RL, Oeffinger KC, Bhatia S, Landier W, Levitt G, et al. A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(4):543–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24445.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026.

Zając-Spychała O, Pawlak MA, Karmelita-Katulska K, Pilarczyk J, Derwich K, Wachowiak J. Long-term brain structural magnetic resonance imaging and cognitive functioning in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia with high-dose methotrexate chemotherapy alone or combined with CNS radiotherapy at reduced total dose to 12 Gy. Neuroradiology. 2017;59(2):147–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-016-1777-8.

Sherief LM, Sanad R, ElHaddad A, Shebl A, Abdelkhalek ER, Elsafy ER, et al. A Cross-sectional Study of Two Chemotherapy Protocols on Long Term Neurocognitive Functions in Egyptian Children Surviving Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2018;14(4):253–60. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573396314666181031134919.

Halsey C, Buck G, Richards S, Vargha-Khadem F, Hill F, Gibson B. The impact of therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia on intelligence quotients; results of the risk-stratified randomized central nervous system treatment trial MRC UKALL XI. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-8722-4-42.

Spiegler BJ, Kennedy K, Maze R, Greenberg ML, Weitzman S, Hitzler JK, et al. Comparison of long-term neurocognitive outcomes in young children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with cranial radiation or high-dose or very high-dose intravenous methotrexate. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(24):3858–64. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2006.05.9055.

Zając-Spychała O, Pawlak M, Karmelita-Katulska K, Pilarczyk J, Jończyk-Potoczna K, Przepióra A, et al. Anti-leukemic treatment-induced neurotoxicity in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: impact of reduced central nervous system radiotherapy and intermediate- to high-dose methotrexate. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59(10):2342–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2018.1434879.

Edelmann MN, Daryani VM, Bishop MW, Liu W, Brinkman TM, Stewart CF, et al. Neurocognitive and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Adult Survivors of Childhood Osteosarcoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(2):201–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4398.

Liu W, Cheung YT, Conklin HM, Jacola LM, Srivastava D, Nolan VG, et al. Evolution of neurocognitive function in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with chemotherapy only. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. 2018;12(3):398–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0679-7.

Fellah S, Cheung YT, Scoggins MA, Zou P, Sabin ND, Pui CH, et al. Brain Activity Associated With Attention Deficits Following Chemotherapy for Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(2):201–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy089.

Jansen NC, Kingma A, Schuitema A, Bouma A, Veerman AJ, Kamps WA. Neuropsychological outcome in chemotherapy-only-treated children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(18):3025–30. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.12.4149.

Jacola LM, Krull KR, Pui CH, Pei D, Cheng C, Reddick WE, et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Neurocognitive Outcomes in Survivors of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treated on a Contemporary Chemotherapy Protocol. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(11):1239–47. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.64.3205.

Grönroos MH, Jahnukainen T, Möttönen M, Perkkiö M, Irjala K, Salmi TT. Long-term follow-up of renal function after high-dose methotrexate treatment in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51(4):535–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21650.

Mulder RL, Knijnenburg SL, Geskus RB, van Dalen EC, van der Pal HJ, Koning CC, et al. Glomerular function time trends in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a longitudinal study. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2013;22(10):1736–46. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-13-0036.

Lequin MH, van der Shuis IM, Van Rijn RR, Hop WC, van ven Huevel-Eibrink MM, MuinckKeizer-Schrama SM, et al. Bone mineral assessment with tibial ultrasonometry and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. J Clin Densitom. 2002;5(2):167–73. https://doi.org/10.1385/jcd:5:2:167.

Tillmann V, Darlington AS, Eiser C, Bishop NJ, Davies HA. Male sex and low physical activity are associated with reduced spine bone mineral density in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2002;17(6):1073–80. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.6.1073.

van der Sluis IM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Hählen K, Krenning EP, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM. Bone mineral density, body composition, and height in long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;35(4):415–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/1096-911x(20001001)35:4%3c415::aid-mpo4%3e3.0.co;2-9.

Cheung YT, Sabin ND, Reddick WE, Bhojwani D, Liu W, Brinkman TM, et al. Leukoencephalopathy and long-term neurobehavioural, neurocognitive, and brain imaging outcomes in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia treated with chemotherapy: a longitudinal analysis. The Lancet Haematology. 2016;3(10):e456–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3026(16)30110-7.

Surtees R, Clelland J, Hann I. Demyelination and single-carbon transfer pathway metabolites during the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia: CSF studies. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16(4):1505–11. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1998.16.4.1505.

Quinn CT, Griener JC, Bottiglieri T, Hyland K, Farrow A, Kamen BA. Elevation of homocysteine and excitatory amino acid neurotransmitters in the CSF of children who receive methotrexate for the treatment of cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15(8):2800–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1997.15.8.2800.

Wen J, Maxwell RR, Wolf AJ, Spira M, Gulinello ME, Cole PD. Methotrexate causes persistent deficits in memory and executive function in a juvenile animal model. Neuropharmacology. 2018;139:76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.07.007.

Howard SC, McCormick J, Pui CH, Buddington RK, Harvey RD. Preventing and Managing Toxicities of High-Dose Methotrexate. Oncologist. 2016;21(12):1471–82. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0164.

den Bakker E, Gemke R, Bökenkamp A. Endogenous markers for kidney function in children: a review. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2018;55(3):163–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2018.1427041.

Laskin BL, Nehus E, Goebel J, Khoury JC, Davies SM, Jodele S. Cystatin C-estimated glomerular filtration rate in pediatric autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2012;18(11):1745–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.06.006.

Nehus EJ, Laskin BL, Kathman TI, Bissler JJ. Performance of cystatin C-based equations in a pediatric cohort at high risk of kidney injury. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2013;28(3):453–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-012-2341-3.

den Hoed MA, Klap BC, te Winkel ML, Pieters R, van Waas M, Neggers SJ, et al. Bone mineral density after childhood cancer in 346 long-term adult survivors of childhood cancer. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2015;26(2):521–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2878-z.

Fan C, Georgiou KR, King TJ, Xian CJ. Methotrexate toxicity in growing long bones of young rats: a model for studying cancer chemotherapy-induced bone growth defects in children. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011: 903097. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/903097.

Thomas IH, Donohue JE, Ness KK, Dengel DR, Baker KS, Gurney JG. Bone mineral density in young adult survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3248–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23912.

Limond JT, S; Bull, KS; Calaminus, G; Lemiere, J; Traunwieser, T; van Santen, HM, Weiler, L; Spoudeas, HA; Chevignard, M. Quality of survival assessment in European childhood brain tumour trials, for children below the age of 5 years. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2020(25):59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2019.10.002.

Jacola LP, M; Lemiere, J; Hudson, MH; Thomas S. Assessment and Monitoring of Neurocognitive Function in Pediatric Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2021(39(16)):1696–704. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.02444.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this review. KS had the idea for the manuscript. ED and MO performed the literature search and the data analysis. ED drafted the manuscript which was critically reviewed by KS, MB and MO. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable for systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for systematic review.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplemental S1. Recommendation for late effects screening in different long-term follow-up care guidelines. Supplemental S2. Search strategy in PubMed. Supplemental S3. Detailed summary of eligible studies on late effects assessed by neuropsychological testing, n = 10 studies. Supplemental S4. Detailed summary of eligible studies on kidney function, n = 2 studies. Supplemental S5. Detailed summary of eligible studies on bone health, n = 3 studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Daetwyler, E., Bargetzi, M., Otth, M. et al. Late effects of high-dose methotrexate treatment in childhood cancer survivors—a systematic review. BMC Cancer 22, 267 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-09145-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-09145-0