Abstract

Background

Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix (NECC) is a rare variant of cervical cancer. The prognosis of women with NECC is poor and there is no standardized therapy for this type of malignancy based on controlled trials.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature search of the databases PubMed and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify clinical trials describing the management and outcome of women with NECC.

Results

Three thousand five hundred thirty-eight cases of NECC in 112 studies were identified. The pooled proportion of NECC among women with cervical cancer was 2303/163470 (1.41%). Small cell NECC, large cell NECC, and other histological subtypes were identified in 80.4, 12.0, and 7.6% of cases, respectively. Early and late stage disease presentation were evenly distributed with 1463 (50.6%) and 1428 (49.4%) cases, respectively. Tumors expressed synaptophysin (424/538 cases; 79%), neuron-specific enolase (196/285 cases; 69%), chromogranin (323/486 cases; 66%), and CD56 (162/267; 61%). The most common primary treatment was radical surgery combined with chemotherapy either as neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy, described in 42/48 studies. Radiotherapy-based primary treatment schemes in the form of radiotherapy, radiochemotherapy, or radiotherapy with concomitant or followed by chemotherapy were also commonly used (15/48 studies). There is no standard chemotherapy regimen for NECC, but cisplatin/carboplatin and etoposide (EP) was the most commonly used treatment scheme (24/40 studies). Overall, the prognosis of women with NECC was poor with a mean recurrence-free survival of 16 months and a mean overall survival of 40 months. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted agents were reported as being active in three case reports.

Conclusion

NECC is a rare variant of cervical cancer with a poor prognosis. Multimodality treatment with radical surgery and neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide with or without radiotherapy is the mainstay of treatment for early stage disease while chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide or topotecan, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab is appropriate for women with locally advanced or recurrent NECC. Immune checkpoint inhibitors may be beneficial, but controlled evidence for their efficacy is lacking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Neuroendocrine neoplasias (NENs) are aggressive malignancies derived from neuroendocrine cells. The term neuroendocrine refers to the fact that the tumor cells originate from the embryonic neuroectoderm and display an immunohistochemical profile consistent with endocrine glandular cells [1]. They may or may not secrete peptide hormones. In humans, NENs are typically located in the gastrointestinal tract, the pancreas, and the lungs and are subdivided in well-differentiated NENs and poorly differentiated NENs [2]. Well-differentiated NENs include neuroendocrine tumors (NET) G1 (also known as typical carcinoid), NET G2 (also known as atypical carcinoid), and NET G3. Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) include small cell NEC and large cell NEC (Table 1).

Rarely, NENs may also occur in other organs such as the female genital tract [3]. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix (NECC) is an aggressive histological variant of cervical cancer accounting for about 1–1.5% of all cervical cancers [1, 4]. Small cell NEC is the most common type of NECC, whereas well-differentiated NETs, especially NET G1 (typical carcinoid) and NET G2 (atypical carcinoid), are very rare at this location [5]. Grading of NECC is similar to NEN of other locations like lung or the digestive system (Table 1). Due to the rarity of this malignancy, the management of NECC is difficult and associated with uncertainty. An interdisciplinary approach is necessary, because most studies investigating the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors have been performed in patients with tumors in organs other than the cervix, mostly the lung and pancreas [4, 6]. Specifically, neuroendocrine tumors mainly occur in the lungs, and thus treatment schedules for neuroendocrine tumors originating in other organs are similar to those used in small cell lung cancer. The biology of NECC is different from squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the cervix regarding a number of characteristics. For example, NECC is more likely to invade the lymph-vascular space and to spread to the regional lymph node basin at the time of diagnosis. Also, local and distant relapses occur more often in NECC, and the 5-year overall survival is significantly poorer with around 30% compared to > 65% for squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix [1, 4]. Thus, the aggressive nature of NECC resembles that of small cell lung cancer which, at the time of initial diagnosis, is rarely localized and mostly locally advanced or metastasized.

Positive immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers like synaptophysin (SYN), chromogranin (CHG), CD56 (N-CAM), and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) is diagnostic for NECC. For establishing the diagnosis, positive staining of at least two neuroendocrine markers is recommended. SYN and CD56 are the most sensitive markers. In some cases of small cell NECC, however, expression of neuroendocrine markers may be negative. Differential diagnosis of NECC includes metastasis of extracervical NEC (e.g. lung or gastro-entero-pancreatic NEC) and extracervical NEC with local wide tumor spread (e.g. urinary bladder, rectum, or Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin). NECC must be distinguished from lymphomas, poorly-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas, and sarcomas or melanomas with morphological small cell-like features. Furthermore, large cell NECC may be positive for p63, a marker strongly expressed in squamous cell carcinomas. In this case, however, positive immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers excludes the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. While isolated neuroendocrine cells may occur in squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas, these tumors should not be interpreted as NECs if they lack the morphological features of NECs.

NSE is not only expressed on the surface of NECC tumor cells, but is also present in the serum of the majority of patients and may thus be used as a serum tumor marker for NECC. For example, in a series of six patients with small cell NECC and 13 patients with squamous cell cervical carcinoma, elevated serum levels of NSE were noted in four of six patients with NECC, but in none of the patients with squamous cell carcinoma [7]. Similar to squamous cell cervical carcinoma, high-risk HPV DNA has been detected in the majority of small cell and large cell NECC [8]. In a recent meta-analysis, Castle et al. [9] analyzed HPV infection data in 403 cases of small cell and 45 cases of large cell NECC. They found that 85 and 88% of cases were HPV positive, respectively. The predominant subtypes were HPV18 and HPV16. The authors conclude that HPV infection is the underlying cause for most cases of NECC and that most if not all cases could thus be prevented by prophylactic HPV vaccination.

No treatment schemes for NECC based on prospective clinical trials are currently available due to the rarity of this malignancy. Many authors have therefore used multimodality approaches, mainly derived from the therapy of cervical cancer in general as well as from neuroendocrine tumors of the lung in particular. In 2011, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) published a clinical document on the management of women with NECC [10]. They also recommend a multimodality therapeutic strategy. Regarding chemotherapy, the SGO recommends etoposide/platinum-based chemotherapies for NECC but not for well differentiated carcinoid tumors, which should be managed similar to gastroenteropancreatic NETs. The Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG), in 2014, also published a consensus review on the treatment of small cell NECC [11]. They recommend radical surgery for early stage disease, either primarily or after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. For patients with advanced stage disease, the GCIG recommends chemoradiation or systemic chemotherapy consisting of etoposide and cisplatin. In line with the SCG and GCIG recommendations, treatment schemes for patients with NECC in the literature usually consist of radical hysterectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for early stage disease. For locally advanced and metastatic disease, definitive concurrent chemoradiation, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery, or chemotherapy alone have been described [1, 4]. Various chemotherapy regimens have been reported in women with NECC and they usually differ from those typically used in squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix. For example, Yin et al. used a combination of cisplatin and etoposide in 23 cases of NECC [12]. Other chemotherapy regimens described in the literature are cisplatin/irinotecan [13], carboplatin/paclitaxel [14], and cisplatin/vincristine/bleomycin [15].

To highlight the clinical characteristics, management, and prognosis of women with NECC, we report the results of a systematic review of the literature with cohort studies, case series, and case reports of women with NECC. We discuss the most common therapies and respective outcomes of this malignancy.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature search of the databases PubMed and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials using the search terms (“neurosecretory systems”[MeSH Terms] OR (“neurosecretory”[All Fields] AND “systems”[All Fields]) OR “neurosecretory systems”[All Fields] OR “neuroendocrine”[All Fields]) AND (“uterine cervical neoplasms”[MeSH Terms] OR (“uterine”[All Fields] AND “cervical”[All Fields] AND “neoplasms”[All Fields]) OR “uterine cervical neoplasms”[All Fields] OR (“cervical”[All Fields] AND “cancer”[All Fields]) OR “cervical cancer”[All Fields]) AND (“therapy”[Subheading] OR “therapy”[All Fields] OR “treatment”[All Fields] OR “therapeutics”[MeSH Terms] OR “therapeutics”[All Fields]). After screening all abstracts of the publications identified by the initial search, studies and case reports reporting on women with NECC were included in the analysis. Suitability of studies was defined for the purpose of this review as reporting on the clinical or biological characteristics, treatment, or clinical outcomes of patients with large cell NECC, small cell NECC, cervical carcinoid tumor, or atypical cervical carcinoid tumor with or without concomitant features of differentiation [16]. In the next step, studies not reporting individual data of women with NECC, duplicate publications, and studies reporting on women with neuroendocrine tumors metastatic to the cervix were excluded. All remaining studies were then retrieved in full and a cross reference search was performed and additional suitable studies reporting on women with NECC as defined above were added to the analysis. Data were extracted, summarized, and analyzed using summary descriptive statistics. Data are given as means or medians where appropriate. No comparative statistics were used.

Results

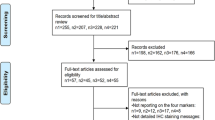

A systematic literature search of the databases PubMed and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials was performed on 21–10-2017 and identified 453 citations. After screening all abstracts, 124 citations were included in the analysis [1, 7, 8, 12,13,14, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134]. Two studies not reporting individual data of women with NECC, double publications, and a study reporting on women with neuroendocrine tumors metastatic to the cervix were excluded [1, 12, 119]. The 121 selected studies were then retrieved in full and a cross reference search was performed which identified 26 additional studies reporting on women with NECC as defined above [15, 135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159]. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the literature search.

We included 147 studies in the final analysis. Table 2 shows study and patient characteristics of 112 studies with individual patient data suitable for pooled analysis. Among these 112 studies, we found 17 retrospective cohort studies, 49 retrospective cases series, and 46 case reports. No prospective studies or interventional trials were identified. Only 8 studies reported on ≥50 patients with NECC describing 130 [59], 100 [100], 68 [71], 64 [129], 61 [142], 57 [134], and 50 [96] cases, respectively. One registry study included 1896 patients without reporting individual patient data [145]. In summary, 3538 cases of NECC have been reported in the literature. Seventeen studies described the total number of cervical cancer patients, among which NECC cases were identified, thus allowing for a calculation of the incidence of NECC among cervical cancer cases. The respective incidences given in these studies were 6/73 (8.22%) [75], 130/2108 (6.17%) [59], 14/389 (3.60%) [108], 10/365 (2.74%) [122], 12/452 (2.65%) [76], 14/649 (2.16%) [103], 44/2835 (1.55%) [109], 1896/127332 (1.49%) [145], 9/677 (1.33%) [56], 31/2385 (1.30%) [48], 25/2201 (1.14%) [120], 11/1370 (0.80%) [117], 64/9474 (0.68%) [129], 14/2074 (0.68%) [150], 6/972 (0.62%) [101], 10/2096 (0.48%) [62], and 7/8018 (0.09%) [123] for a pooled rate of 2303/163470 (1.41%) cases.

The most common histological subtype of NECC was small cell NECC. Specifically, small cell NECC, large cell NECC, and other histological subtypes were identified in 80.4, 12.0, and 7.6% of cases, respectively. Early (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] stages I to IIA) and late (FIGO stages IIB to IV) stage disease presentation were evenly distributed with 1463 (50.6%) and 1428 (49.4%) cases, respectively.

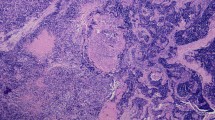

The immunohistochemical profiles of NECC demonstrated expression of SYN (424/538 cases; 79%), NSE (196/285 cases; 69%), CHG (323/486 cases; 66%), and CD56 (162/267; 61%) as the most typical markers of NECC. Only a fraction of the published studies analyzed molecular tumor profiles. Among them, the mutations most often identified were in the p53 (22/86; 26%), KRAS (7/60; 12%), PIK3CA (8/44; 18%), and c-myc (8/15; 53%) genes, respectively. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) was found to be present in 16/53 (30%) cases. Additional file 1: Figure S1 demonstrates immunohistochemical stainings of a small cell NECC with positive staining for CD56 (N-CAM) and the proliferation marker Ki-67.

Treatment modalities and outcomes are shown in Table 3. The most common primary treatment modality of NECC was radical surgery combined with chemotherapy either as neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. Specifically, radical surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy were described in 21/48 studies. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery with or without adjuvant therapies (radiotherapy, radiochemotherapy, or chemotherapy) were described in 12/48 studies. Radiotherapy-based primary treatment schemes in the form of radiotherapy, radiochemotherapy with cisplatin, or radiotherapy with concomitant or followed by chemotherapy were also commonly used (15/48 studies). There was no retrospective or prospective comparison of the efficacy of surgery-based, chemotherapy-based, and radiotherapy-based treatment schemes within comparable disease stages in the published studies. After recurrence of NECC, chemotherapy was used in most studies (7/10 studies), followed by radiotherapy (3/10 studies), and surgery (2/10 studies).

There is no standard chemotherapy regimen for NECC, but cisplatin/carboplatin and etoposide (EP) was the most commonly used treatment scheme (24/40 studies), similar to the treatment routinely used for small cell lung cancer. EP combined with other substances such as bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, or doxorubicin was reported in another 6/40 studies, making EP alone or in combination by far the most commonly used cytotoxic regimen. Other commonly used cytotoxic regimens in the primary therapy setting (neoadjuvant or adjuvant) were cisplatin/carboplatin and paclitaxel (7/40 studies) and cisplatin combined with irinotecan (4/40 studies). Other regimes such as 5-fluorouracil/cisplatin, vincristine/cisplatin/bleomycin, vincristine/adriamycin/cisplatin, and irinotecan/cisplatin/paclitaxel were only rarely used. In women with recurrent NECC, EP alone or in combination with other cytotoxic drugs was also the most commonly used cytotoxic regimen (5/8 studies). Overall, the prognosis of women with NECC was poor. The recurrence-free survival was short with a mean duration of 16 months and the mean overall survival duration of women with NECC was 40 months. In a pooled analysis of all studies reporting absolute survival rates, the 2-year- and 5-year overall survival rates were 50 and 34%, respectively.

Targeted therapies and immune-checkpoint inhibitors were only described in three studies [102, 144, 149]. Paraghamian et al. used nivolumab in a patient with recurrent, metastatic, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1)-negative small cell NECC, who experienced a complete response [149]. Sharabi et al. report a patient with metastatic, chemotherapy-refractory NECC with bowel obstruction due to a large tumor burden [102]. Liquid biopsy demonstrated a high number of tumor mutations. She was treated with radiotherapy combined with nivolumab and experienced a near-complete systemic resolution of disease for at least 10 months. Lastly. Lyons et al. used the mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MEK)-inhibitor trametinib in a woman with recurrent small cell NECC and a Kirsten rat sarcoma gene (KRAS)-mutated tumor [144]. This patient also experienced a complete response.

The largest cohort of women with NECC was published by Margolis et al. [145]. Using the National Cancer Database (NCDB), the authors identified 1896 patients with NECC. These patients were younger, more often white, and diagnosed with metastatic disease at presentation compared to women with squamous cell cervical cancer. In a multivariable analysis, NECC patients of all tumor stages had a significantly higher risk of death compared to women with squamous cell cervical cancer. Three other large cohorts analyzed data sets of 188 [37], 130 [59], and 100 [100] cases, respectively. Cohen et al. summarized the characteristics and treatment results of 188 patients most of whom had early stage disease (n = 135 with FIGO stages I-IIA) [37]. The 5-year disease-specific survival in FIGO stages I-IIA, IIB-IVA, and IVB disease were 36.8, 9.8, and 0%, respectively. In this patient cohort, adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation was associated with a significantly improved survival in all patients. Consequently, use of chemotherapy or chemoradiation was an independent prognostic factor for improved survival. Robin et al. used the National Cancer Data Base to identify 100 women with locally advanced NECC treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy [100]. There was a substantial improvement in overall survival when brachytherapy was administered in addition to external beam radiotherapy resulting in an improved median survival of 48.6 vs. 21.6 months. Intaraphet et al. looked at 130 patients with small cell NECC and identified older age and locoregional lymph node involvement as the most important prognostic factors among surgically treated patients [59].

The largest series of women analyzing the treatment efficacy of chemotherapy among women with recurrent NECC was published by Frumovitz et al. [140]. They compared 13 patients who received the combination of topotecan, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab (TPB) with 21 patients receiving other regimens, mostly a platinum-based regimen with or without a taxane. TPB was associated with a significantly improved outcome. For example, the median progression-free survival was 7.8 months for TPB and 4.0 months for non-TPB regimens and the median overall survival was 9.7 months for TPB and 9.4 months for the non-TPB regimens. Eight women (62%) who received TPB versus four (19%) who received non-TPB regimens were on treatment for > 6 months, and four patients (31%) in the TPB group versus two (10%) in the non-TPB group were on treatment for > 12 months.

The bulk of studies identified in this systematic review were small case series (43.8%) and case reports (41.1%). As expected, the heterogeneity among these studies with low numbers of NECC patients was considerable. However, as shown in Table 3, most patients were treated with radical surgery and adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy, whereas chemotherapy alone or radio/chemo/therapy alone were rarely used. Long-term survivors among these women were almost exclusively found in cases with early stage disease at initial presentation, complete tumor resection, and chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy.

Discussion

NECC is an aggressive histological variant of cervical cancer accounting for 1.4% of all cervical cancers. The management of NECC is difficult and is associated with uncertainty. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the literature and identified data of 3538 NECC cases from 112 studies. We found that NECC is a rare variant of cervical cancer with small cell NECC being the most common histological subtype. This tumor carries a poor prognosis with a mean overall survival of 40 months and a 5-year overall survival rate of 34%. Multimodality treatment with radical surgery and adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin is the mainstay of treatment for early stage disease while combined radiochemotherapy and chemotherapy are appropriate for women with locally advanced or recurrent NECC. A large number of chemotherapy regimens have been described in the treatment of patients with NECC but cisplatin/carboplatin and etoposide alone or in combination with other substances have been described in more than two thirds of the published studies. Novel therapeutics such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies may be beneficial, but evidence for their efficacy is lacking.

Although there is no standard of care regarding the choice of chemotherapy for women with NECC, we found that cisplatin/carboplatin and etoposide was the most commonly used regimen in the primary treatment and may thus be regarded as an informal standard. Of note, this combination was described in 30/40 studies. The exact dosage and therapy duration of this scheme, however, varied considerably in the published studies. For example, Baykal et al. used cisplatin 80 mg/m2 on day 1 together with etoposide 120 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, and 3 in a 21 day cycle [26]. Intaraphet et al. used cisplatin 75 mg/m2 and etoposide 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks [59]. Hoskins et al. used etoposide (40 mg/m2/d) and cisplatin (25 mg/m2/d) over 5 consecutive days starting on days 1, 15, 29, and 43 and combined this scheme with locoregional irradiation started on day 15 [14].

In women with recurrent NECC, cisplatin/etoposide alone or in combination with other cytotoxic drugs was also the most commonly used cytotoxic regimen described in 5/8 studies. Of note, women with recurrent disease who had already been treated with cisplatin/carboplatin and etoposide in the primary setting might benefit from a triplet regimen consisting of topotecan, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. In the largest series of women with recurrent NECC, Frumovitz et al. found that the combination of topotecan, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab was superior to platinum-based regimens with or without a taxane [140]. Thus, in women who already had received cisplatin/carboplatin and etoposide in the primary treatment, topotecan, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab might be an appropriate choice.

Women with NECC have a poor prognosis irrespective of the treatments used. Even with aggressive treatment schemes involving radical surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the mean 5-year overall survival rate was only 34% in our pooled analysis of the published data. Therefore, new treatment concepts are warranted for this subgroup of cervical cancer patients. Targeted therapies and immune-checkpoint inhibitors might be such new treatment options for NECC. In two case reports, nivolumab led to durable remissions in patients with recurrent disease as did the MEK-inhibitor trametinib in a woman with recurrent small cell NECC and a KRAS-mutated tumor [102, 144, 149]. Clearly, this is not a broad evidence base. On the other hand, NECC is a very rare disease and in view of a reasonable alternative, these novel agents might be used in women with recurrent NECC and progression after conventional chemotherapy regimens such as cisplatin/etoposide or topotecan, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. When comparing these regimens to those usually used for small cell lung cancer, platinum compounds, etoposide, topotecan and anthracyclines are familiar substances whereas paclitaxel or bevacizumab are rarely used in small cell lung cancer.

Conclusions

We found that NECC is a rare form of cervical cancer with a poor prognosis. Due to the small number of cases and the retrospective nature of this analysis, conclusions are limited, but multimodality treatment with radical surgery and adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin is the mainstay of treatment for early stage disease while combined radiochemotherapy and chemotherapy are appropriate for women with locally advanced or recurrent NECC. In light of the poor prognosis of women with NECC despite aggressive treatment, novel therapeutics such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted agents should be incorporated into the management even without controlled evidence.

Abbreviations

- CHG:

-

Chromogranin

- EP:

-

Cisplatin/carboplatin and etoposide

- FIGO:

-

International federation of gynecology and obstetrics

- GCIG:

-

Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup

- KRAS:

-

Kirsten rat sarcoma gene

- LOH:

-

Loss of heterozygosity

- MEK-1:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1

- NCDB:

-

National Cancer Database

- NEC:

-

Neuroendocrine carcinoma

- NECC:

-

Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix

- NEN:

-

Neuroendocrine neoplasia

- NET:

-

Neuroendocrine tumor

- NSE:

-

Neuron-specific enolase

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

- SGO:

-

Society of Gynecologic Oncology

- SYN:

-

Synaptophysin

- TPB:

-

Topotecan, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab

References

Gadducci A, Carinelli S, Aletti G. Neuroendrocrine tumors of the uterine cervix: a therapeutic challenge for gynecologic oncologists. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:637–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.12.003.

Kim JY, Hong SM, Ro JY. Recent updates on grading and classification of neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;29:11–6.

Guadagno E, de RG, de Del Basso Caro M. Neuroendocrine tumours in rare sites: differences in nomenclature and diagnostics-a rare and ubiquitous histotype. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:563–74. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203551.

Burzawa J, Gonzales N, Frumovitz M. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of cervical neuroendocrine carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2015;15:805–10. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737140.2015.1047767.

Lax SF, Horn LC, Löning T. Categorization of uterine cervix tumors: What's new in the 2014 WHO classification. Pathologe. 2016;37(6):573–84.

Grande E, Capdevila J, Castellano D, Teulé A, Durán I, Fuster J, et al. Pazopanib in pretreated advanced neuroendocrine tumors: a phase II, open-label trial of the Spanish task force Group for Neuroendocrine Tumors (GETNE). Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1987–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv252.

Chen CA, Wu CC, Juang GT, Wang JF, Chen TM, Hsieh CY. Serum neuron-specific enolase levels in patients with small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Formos Med Assoc. 1994;93:81–3.

Wang HL, Lu DW. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA and expression of p16, Rb, and p53 proteins in small cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:901–8.

Castle PE, Pierz A, Stoler MH. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the attribution of human papillomavirus (HPV) in neuroendocrine cancers of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:422–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.001.

Gardner GJ, Reidy-Lagunes D, Gehrig PA. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gynecologic tract: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) clinical document. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:190–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.011.

Satoh T, Takei Y, Treilleux I, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Ledermann J, Viswanathan AN, et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus review for small cell carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:S102–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000262.

Yin ZM, Yu AJ, Wu MJ, Fang J, Liu LF, Zhu JQ, Yu H. Effects and toxicity of neoadjuvant chemotherapy preoperative followed by adjuvant chemoradiation in small cell neurdendocrine cervical carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2015;36:326–9.

Nasu K, Hirakawa T, Okamoto M, Nishida M, Kiyoshima C, Matsumoto H, et al. Advanced small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy with irinotecan and cisplatin followed by radical surgery. Rare Tumors. 2011;3:e6. https://doi.org/10.4081/rt.2011.e6.

Hoskins PJ, Swenerton KD, Pike JA, Lim P, Aquino-Parsons C, Wong F, Lee N. Small-cell carcinoma of the cervix: fourteen years of experience at a single institution using a combined-modality regimen of involved-field irradiation and platinum-based combination chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3495–501. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.01.501.

Bermúdez A, Vighi S, García A, Sardi J. Neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:32–9. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.2001.6201.

Albores-Saavedra J, Gersell D, Gilks CB, Henson DE, Lindberg G, Santiago H, et al. Terminology of endocrine tumors of the uterine cervix: results of a workshop sponsored by the College of American Pathologists and the National Cancer Institute. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:34–9.

Abdallah R, Bush SH, Chon HS, Apte SM, Wenham RM, Shahzad MMK. Therapeutic dilemma: prognostic factors and outcome for neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:553–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000631.

Abeler VM, Holm R, Nesland JM, Kjørstad KE. Small cell carcinoma of the cervix. A clinicopathologic study of 26 patients. Cancer. 1994;73:672–7.

Abulafia O, Sherer DM. Adjuvant chemotherapy in stage IB neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the cervix. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:740–4.

Agarwal S, Schmeler KM, Ramirez PT, Sun CC, Nick A, Dos Reis R, et al. Outcomes of patients undergoing radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer of high-risk histological subtypes. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:123–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0b013e3181ffccc1.

Albores-Saavedra J, Martinez-Benitez B, Luevano E. Small cell carcinomas and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the endometrium and cervix: polypoid tumors and those arising in polyps may have a favorable prognosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:333–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/PGP.0b013e31815de006.

Alphandery C, Dagrada G, Frattini M, Perrone F, Pilotti S. Neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the cervix associated with endocervical adenocarcinoma: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:589–93.

Ambros RA, Park JS, Shah KV, Kurman RJ. Evaluation of histologic, morphometric, and immunohistochemical criteria in the differential diagnosis of small cell carcinomas of the cervix with particular reference to human papillomavirus types 16 and 18. Mod Pathol. 1991;4:586–93.

Asensio N, Luis A, Costa I, Oliveira J, Vaz F. Meningeal carcinomatosis and uterine carcinoma: three different clinical settings and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:168–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/IGC.0b013e31819a1e1a.

Balega J, Ulbright TM, Look KY. Coexistence of metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11:334–7.

Baykal C, Al A, Tulunay G, Bulbul D, Güler G, Ozer S, Küçükali T. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix. A case report. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2005;59:207–11. https://doi.org/10.1159/000084259.

Bifulco G, Mandato VD, Giampaolino P, Piccoli R, Insabato L, de Rosa N, Nappi C. Small cell neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma with 1-year follow-up: case report and review. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:477–84.

Brown KR, Leitao MM. Cisplatin-induced syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) in a patient with neuroendocrine tumor of the cervix: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010;31:107–8.

Cavalcanti MS, Schultheis AM, Ho C, Wang L, DeLair DF, Weigelt B, et al. Mixed mesonephric adenocarcinoma and high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: case description of a previously unreported entity with insights into its molecular pathogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2017;36:76–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/PGP.0000000000000306.

Cetiner H, Kir G, Akoz I, Gurbuz A, Karateke A. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix associated with cervical-type invasive adenocarcinoma: a report of case and discussion of histogenesis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:438–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00194.x.

Chan JK, Loizzi V, Burger RA, Rutgers J, Monk BJ. Prognostic factors in neuroendocrine small cell cervical carcinoma: A multivariate analysis. Cancer. 2003;97:568–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11086.

Chatterjee S, Chakravorty S, Kapoor P, Chattopadhyay D. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of cervix--a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2005;48:410–2.

Chavez-Blanco A, Taja-Chayeb L, Cetina L, Chanona-Vilchis G, Trejo-Becerril C, Perez-Cardenas E, et al. Neuroendocrine marker expression in cervical carcinomas of non-small cell type. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21:368–74.

Cho SY, Choi M, Ban H-J, Lee CH, Park S, Kim H, et al. Cervical small cell neuroendocrine tumor mutation profiles via whole exome sequencing. Oncotarget. 2017;8:8095–104. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14098.

Chun K-C, Kim D-Y, Kim J-H, Kim Y-M, Kim Y-T, Nam J-H. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel plus platinum followed by radical surgery in early cervical cancer during pregnancy: three case reports. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:694–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyq039.

Chung W-K, Yang J-H, Chang S-E, Lee M-W, Choi J-H, Moon K-C, Koh J-K. A case of cutaneous metastasis of small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:636–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/DAD.0b013e31817e6f27.

Cohen JG, Kapp DS, Shin JY, Urban R, Sherman AE, L-m C, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the cervix: treatment and survival outcomes of 188 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:347.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.019.

Collinet P, Lanvin D, Declerck D, Chevalier-Place A, Leblanc E, Querleu D. Neuroendocrine tumors of the uterine cervix. Clinicopathologic study of five patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;91:51–7.

Conner MG, Richter H, Moran CA, Hameed A, Albores-Saavedra J. Small cell carcinoma of the cervix: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 23 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002;6:345–8. https://doi.org/10.1053/adpa.2002.36661.

Cui S, Lespinasse P, Cracchiolo B, Sama J, Kreitzer MS, Heller DS. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix associated with adenocarcinoma in situ: evidence of a common origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:311–2.

Damian A, Lago G, Rossi S, Alonso O, Engler H. Early detection of bone metastasis in small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix by 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT imaging. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42:216–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0000000000001498.

Delaloge S, Pautier P, Kerbrat P, Castaigne D, Haie-Meder C, Duvillard P, et al. Neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: what disease? What treatment? Report of ten cases and a review of the literature. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2000;12:357–62.

Dikmen Y, Kazandi M, Zekioglu O, Ozsaran A, Terek MC, Erhan Y. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004;270:185–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-003-0482-0.

Donati P, Paolino G, Donati M, Panetta C. Adenocarcinoma of the cervix associated with a neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the cervix in the spectrum of Muir-Torre syndrome. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2015;36:213–5.

Duan X, Ban X, Zhang X, Hu H, Li G, Wang D, et al. MR imaging features and staging of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix with pathological correlations. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:4293–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4327-1.

Emmett M, Gildea C, Nordin A, Hirschowitz L, Poole J. Variations in treatment of cervical Cancer according to tumor morphology-population-based cohort analysis of English National Cancer Registration Data. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:138–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000859.

Frumovitz M, Burzawa JK, Byers LA, Lyons YA, Ramalingam P, Coleman RL, Brown J. Sequencing of mutational hotspots in cancer-related genes in small cell neuroendocrine cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:588–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.04.001.

Ganesan R, Hirschowitz L, Dawson P, Askew S, Pearmain P, Jones PW, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: review of a series of cases and correlation with outcome. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24(6):490. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066896916643385.

Gersell DJ, Mazoujian G, Mutch DG, Rudloff MA. Small-cell undifferentiated carcinoma of the cervix. A clinicopathologic, ultrastructural, and immunocytochemical study of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:684–98.

Gilks CB, Young RH, Gersell DJ, Clement PB. Large cell neuroendocrine corrected carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:905–14.

Grayson W, Rhemtula HA, Taylor LF, Allard U, Tiltman AJ. Detection of human papillomavirus in large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a study of 12 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:108–14.

Gressner O, Sauerbruch T. Secondary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix after radiotherapy for cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.05.027.

Hao H, Itoyama M, Tsubamoto H, Tsujimoto M, Hirota S. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix associated with intestinal variant invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma. Pathol Int. 2011;61:55–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02606.x.

Hara H, Ishii E, Hondo T, Nakagawa M, Teramoto K, Oyama T. Cytological features of atypical carcinoid combined with adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40(8):724. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.21657.

Herrington CS, Graham D, Southern SA, Bramdev A, Chetty R. Loss of retinoblastoma protein expression is frequent in small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix and is unrelated to HPV type. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:906–10.

Horn L-C, Hentschel B, Bilek K, Richter CE, Einenkel J, Leo C. Mixed small cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix: prognostic impact of focal neuroendocrine differentiation but not of Ki-67 labeling index. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10(3):140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.07.019.

Horn L-C, Lindner K, Szepankiewicz G, Edelmann J, Hentschel B, Tannapfel A, et al. p16, p14, p53, and cyclin D1 expression and HPV analysis in small cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25:182–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pgp.0000185406.85685.df.

Hsieh T-C, Wu Y-C, Sun S-S, Yang C-F, Yen K-Y, Liang J-A, Kao C-H. Rare breast and adrenal gland metastases from small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of uterine cervix. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37(3):280. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0b013e31823ea6c4.

Intaraphet S, Kasatpibal N, Siriaunkgul S, Sogaard M, Patumanond J, Khunamornpong S, et al. Prognostic impact of histology in patients with cervical squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5355–60.

Ishida GM, Kato N, Hayasaka T, Saito M, Kobayashi H, Katayama Y, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix: a histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:366–72.

Kajiwara H, Hirabayashi K, Miyazawa M, Nakamura N, Hirasawa T, Muramatsu T, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of somatostatin type 2A receptor in neuroendocrine carcinoma of uterine cervix. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:521–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-008-0760-y.

Kasamatsu T, Sasajima Y, Onda T, Sawada M, Kato T, Tanikawa M. Surgical treatment for neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:225–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.051.

Kim DY, Yun HJ, Lee YS, Lee HN, Kim CJ. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix presenting with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:420–5. https://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2013.56.6.420.

Ko M-L, Jeng C-J, Huang S-H, Shen J, Chen S-C, Tzeng C-R. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix associated with adenocarcinoma. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46:68–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60111-4.

Koch CA, Azumi N, Furlong MA, Jha RC, Kehoe TE, Trowbridge CH, et al. Carcinoid syndrome caused by an atypical carcinoid of the uterine cervix. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4209–13. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.84.11.6126.

Komiyama S, Nishio E, Torii Y, Kawamura K, Oe S, Kato R, et al. A case of primary uterine cervical neuroendocrine tumor with meningeal carcinomatosis confirmed by diagnostic imaging and autopsy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16:581–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-010-0155-5.

Kuji S, Watanabe R, Sato Y, Iwata T, Hirashima Y, Takekuma M, et al. A new marker, insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1), for high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: analysis of 37 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:384–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.11.020.

Kumar S, Nair S, Alexander M. Carcinomatous meningitis occurring prior to a diagnosis of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50:311–2.

Kuroda N, Wada Y, Inoue K, Ohara M, Mizuno K, Toi M, et al. Smear cytology findings of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:636–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.21834.

Lan-Fang L, Hai-Yan S, Zuo-Ming Y, Jian-Qing Z, Ya-Qing C. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: analysis of the prognosis and role of radiation therapy for 43 cases. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2012;33:68–73.

Lee J-M, Lee K-B, Nam J-H, Ryu S-Y, Bae D-S, Park J-T, et al. Prognostic factors in FIGO stage IB-IIA small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated surgically: results of a multi-center retrospective Korean study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:321–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm465.

Lee SW, Nam J-H, Kim D-Y, Kim J-H, Kim K-R, Kim Y-M, Kim Y-T. Unfavorable prognosis of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a retrospective matched case-control study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:411–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181ce427b.

Lee S-W, Lim K-T, Bae DS, Park SY, Kim YT, Kim K-R, Nam J-H. A multicenter study of the importance of systemic chemotherapy for patients with small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2015;79:172–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000367920.

Lee W-J, Lee D-W, Lee M-W, Choi J-H, Moon K-C, Koh J-K. Multiple cutaneous metastases of neuroendocrine carcinoma derived from the uterine cervix. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:494–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02955.x.

Lenczewski A, Terlikowski S, Sulkowska M, Famulski W, Kisielewski W, Kulikowski M. Small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix--an uncommon variant of cervical cancer with neuroendocrine features. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2001;39(Suppl 2):89–90.

Li S, Zhu H. Twelve cases of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix: cytology, histopathology and discussion of their histogenesis. Acta Cytol. 2013;57:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1159/000342516.

Li WWH, Yau TN, Leung CWL, Pong WM, Chan MYM. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix complicating pregnancy. Hong Kong Med J. 2009;15:69–72.

Lin Y, Lin WY, Liang JA, Lu YY, Wang HY, Tsai SC, Kao CH. Opportunities for 2-(18)F fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET/CT in cervical-vaginal neuroendocrine carcinoma: Case series and literature review. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13:760–70. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2012.13.6.760.

Majhi U, Murhekar K, Sundersingh S, Srinivasan V. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of cervix showing neuroendocrine differentiation. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:492–3. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1482.146114.

Mannion C, Park WS, Man YG, Zhuang Z, Albores-Saavedra J, Tavassoli FA. Endocrine tumors of the cervix: morphologic assessment, expression of human papillomavirus, and evaluation for loss of heterozygosity on 1p,3p, 11q, and 17p. Cancer. 1998;83:1391–400.

Markopoulos MC, Lagadas AA, Alexandrou P, Giannakopoulos KC, Polyzos A. Prolonged disease free survival with aggressive adjuvant chemotherapy in a case of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J BUON. 2009;14:322–3.

Marongiu A, Salvati M, D'Elia A, Arcella A, Giangaspero F, Esposito V. Single brain metastases from cervical carcinoma: report of two cases and critical review of the literature. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:937–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-011-0861-4.

Marshall L-J, Sutton CD, White SA, Mackay H, Dennison AR. Syndrome X induced by carcinoid syndrome secondary to a cervical neuroendocrine primary tumour. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72:372–4.

McCluggage WG, Kennedy K, Busam KJ. An immunohistochemical study of cervical neuroendocrine carcinomas: neoplasms that are commonly TTF1 positive and which may express CK20 and P63. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:525–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d1d457.

McGarry RC, Smith C, Seemayer TA. Treatment resistant small cell carcinoma of the cervix. Oncology. 1999;57:293–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000012063.

Nagao S, Miwa M, Maeda N, Kogiku A, Yamamoto K, Morimoto A, et al. Clinical features of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a single-institution retrospective review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:1300–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000495.

Nakata SI, Yamamoto K, Kobayashi Y, Maeda K, Tsuda H, Deguchi M, et al. Excellent results of radiotherapy for neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:777–9.

Niwa K, Nonaka-Shibata M, Satoh E, Hirose Y. Cervical large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma with cytologic presentation: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:977–80.

Ohwada M, Wada T, Saga Y, Tsunoda S, Jobo T, Kuramoto H, et al. C-kit overexpression in neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006;27:53–5.

Perrin L, Bell J, Ward B. Small cell carcinoma of the cervix of neuroendocrine origin causing obstructed labour. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;36:85–7.

Powell JL, McKinney CD. Large cell neuroendocrine tumor of the cervix and human papillomavirus 16: a case report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2008;12:242–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0b013e3181641b4f.

Puig F, Rodrigo C, Muñoz G, Lanzón R. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: report of two cases. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30:321–2.

Pyeon SY, Park JY, Ulak R, Seol HJ, Lee JM. Isolated brain metastasis from uterine cervical cancer: a case report and review of literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2015;36:602–4.

Ramalingam P, Malpica A, Deavers MT. Mixed endocervical adenocarcinoma and high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix with ovarian metastasis of the former component: a report of 2 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2012;31:490–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/PGP.0b013e31824735a5.

Rashed MM, Bekele A. Neuroendocrine differentiation in a case of cervical cancer. Pan Afr Med J. 2010;6:4.

Rekhi B, Patil B, Deodhar KK, Maheshwari A, A Kerkar R, Gupta S, et al. Spectrum of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix, including histopathologic features, terminology, immunohistochemical profile, and clinical outcomes in a series of 50 cases from a single institution in India. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2012.01.009.

Rhemtula H, Grayson W, van Iddekinge B, Tiltman A. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix--a clinicopathological study of five cases. S Afr Med J. 2001;91:525–8.

Rhiem K, Possover M, Gossmann A, Drebber K, Mallmann P, Ulrich U. “Occult” neuroendocrine component and rare metastatic pattern in cervical cancer: report of a case and brief review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2007;28:139–41.

Ribeiro-Silva A, Novello-Vilar A, Cunha-Mercante AM, de Angelo Andrade LAL. Malignant mixed Mullerian tumor of the uterine cervix with neuroendocrine differentiation. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:223–7.

Robin TP, Amini A, Schefter TE, Behbakht K, Fisher CM. Brachytherapy should not be omitted when treating locally advanced neuroendocrine cervical cancer with definitive chemoradiation therapy. Brachytherapy. 2016;15:845–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brachy.2016.08.007.

Sato Y, Shimamoto T, Amada S, Asada Y, Hayashi T. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathological study of six cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2003;22:226–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PGP.0000071046.12278.D1.

Sharabi A, Kim SS, Kato S, Sanders PD, Patel SP, Sanghvi P, et al. Exceptional response to Nivolumab and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) in neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma with high tumor mutational burden: management considerations from the center for personalized Cancer therapy at UC san Diego Moores Cancer center. Oncologist. 2017;22:631–7. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0517.

Sheets EE, Berman ML, Hrountas CK, Liao SY, DiSaia PJ. Surgically treated, early-stage neuroendocrine small-cell cervical carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:10–4.

Silva-Meléndez PE, Escobar PF, Héctor S, Gutiérrez S, Rodríguez M. Small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a case report and literature review. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2015;107:55–7.

Singh S, Redline R, Resnick KE. Fertility-sparing management of a stage IB1 small cell neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma with radical abdominal trachelectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2015;13:5–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gore.2015.04.004.

Siriaunkgul S, Utaipat U, Suwiwat S, Settakorn J, Sukpan K, Srisomboon J, Khunamornpong S. Prognostic value of HPV18 DNA viral load in patients with early-stage neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:3281–5.

Sisti G, Buccoliero AM, Novelli L, Sansovini M, Severi S, Pieralli A, et al. A case of metachronous double primary neuroendocrine cancer in pancreas/ileum and uterine cervix. Ups J Med Sci. 2012;117:453–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/03009734.2012.707254.

Sitthinamsuwan P, Angkathunyakul N, Chuangsuwanich T, Inthasorn P. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathological study. J Med Assoc Thail. 2013;96:83–90.

Sodsanrat K, Saeaib N, Liabsuetrakul T. Comparison of clinical manifestations and survival outcomes between neuroendocrine tumor and squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: results from a tertiary Center in Southern Thailand. J Med Assoc Thail. 2015;98:725–33.

Straughn JM, Richter HE, Conner MG, Meleth S, Barnes MN. Predictors of outcome in small cell carcinoma of the cervix--a case series. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;83:216–20. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.2001.6385.

Strinić T, Tomić S, Pejković L, Eterović D, Forko JI, Karelović DA. Cure from the small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix following conventional surgery. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2000;122:387–9.

Tangjitgamol S, Ramirez PT, Sun CC, See HT, Jhingran A, Kavanagh JJ, Deavers MT. Expression of HER-2/neu, epidermal growth factor receptor, vascular endothelial growth factor, cyclooxygenase-2, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor in small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic and prognostic study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:646–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00121.x.

Tangjitgamol S, Manusirivithaya S, Choomchuay N, Leelahakorn S, Thawaramara T, Pataradool K, Suekwatana P. Paclitaxel and carboplatin for large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33:218–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00509.x.

Teefey P, Orr B, Vogt M, Roberts W. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix during pregnancy: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep. 2012;2:73–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gynor.2012.03.003.

Toki T, Katayama Y, Motoyama T. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix associated with micro-invasive squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma in situ. Pathol Int. 1996;46:520–5.

Trinh XB, Bogers JJ, van Marck EA, Tjalma WAA. Treatment policy of neuroendocrine small cell cancer of the cervix. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2004;25:40–4.

Tsunoda S, Jobo T, Arai M, Imai M, Kanai T, Tamura T, et al. Small-cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:295–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.15219.x.

Turner WA, Gallup DG, Talledo OE, Otken LB, Guthrie TH. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix complicated by pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:80S–3S.

van Nagell JR, Donaldson ES, Wood EG, Maruyama Y, Utley J. Small cell cancer of the uterine cervix. Cancer. 1977;40:2243–9.

van Nagell JR, Powell DE, Gallion HH, Elliott DG, Donaldson ES, Carpenter AE, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer. 1988;62:1586–93.

Viswanathan AN, Deavers MT, Jhingran A, Ramirez PT, Levenback C, Eifel PJ. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: outcome and patterns of recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.12.027.

Walker AN, Mills SE, Taylor PT. Cervical neuroendocrine carcinoma: a clinical and light microscopic study of 14 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1988;7:64–74.

Wang K-L, Wang T-Y, Huang Y-C, Lai JC-Y, Chang T-C, Yen M-S. Human papillomavirus type and clinical manifestation in seven cases of large-cell neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108:428–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60088-7.

Wang K-L, Yang Y-C, Wang T-Y, Chen J-R, Chen T-C, Chen H-S, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic retrospective study of 31 cases with prognostic implications. J Chemother. 2006;18:209–16. https://doi.org/10.1179/joc.2006.18.2.209.

Wang Y, Mei K, Xiang MF, Li JM, Xie RM. Clinicopathological characteristics and outcome of patients with small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: case series and literature review. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2013;34:307–10.

Weed JC, Graff AT, Shoup B, Tawfik O. Small cell undifferentiated (neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:44–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00120-0.

Wistuba II, Thomas B, Behrens C, Onuki N, Lindberg G, Albores-Saavedra J, Gazdar AF. Molecular abnormalities associated with endocrine tumors of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;72:3–9. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.1998.5248.

Wu P-Y, Cheng Y-M, New GH, Chou C-Y, Chiang C-T, Tsai H-W, Huang Y-F. Case report: term birth after fertility-sparing treatments for stage IB1 small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0404-0.

Yin ZM, Yu AJ, Wu MJ, Zhu JQ, Zhang X, Chen JH, et al. Prognostic factors and treatment comparison in small cell neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2014;35:259–63.

Yoshida Y, Sato K, Katayama K, Yamaguchi A, Imamura Y, Kotsuji F. Atypical metastatic carcinoid of the uterine cervix and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:636–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01402.x.

Yousef I, Siyam F, Layfield L, Freter C, Sowers JR. Cervical neuroendocrine tumor in a young female with lynch syndrome. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014;35:89–94.

Yuan L, Jiang H, Lu Y, Guo S-W, Liu X. Prognostic factors of surgically treated early-stage small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:1315–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000496.

Yun K, Cho NP, Glassford GN. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a report of a case with coexisting cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and human papillomavirus 16. Pathology. 1999;31:158–61.

Zaid T, Burzawa J, Basen-Engquist K, Bodurka DC, Ramondetta LM, Brown J, Frumovitz M. Use of social media to conduct a cross-sectional epidemiologic and quality of life survey of patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: a feasibility study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:149–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.10.015.

Baggar S, Ouahbi H, Azegrar M, El M'rabet FZ, Arifi S, Mellas N. Carcinome neuroendocrine du col utérin: À propos d’un cas avec revue de la littérature. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:82. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.27.82.10902.

Bellefqih S, Khalil J, Mezouri I, Kebdani T, Benjaafar N. Carcinome neuroendocrine à petites cellules du col utérin: À propos de six cas et revue de la littérature. Cancer Radiother. 2014;18:201–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canrad.2014.01.003.

Boruta DM, Schorge JO, Duska LA, Crum CP, Castrillon DH, Sheets EE. Multimodality therapy in early-stage neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:82–7. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.2000.6118.

Chang TC, Lai CH, Tseng CJ, Hsueh S, Huang KG, Chou HH. Prognostic factors in surgically treated small cell cervical carcinoma followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 1998;83:712–8.

Dongol S, Tai Y, Shao Y, Jiang J, Kong B. A retrospective clinicopathological analysis of small-cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:71–5. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2013.193.

Frumovitz M, Munsell MF, Burzawa JK, Byers LA, Ramalingam P, Brown J, Coleman RL. Combination therapy with topotecan, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab improves progression-free survival in recurrent small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:46–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.040.

Futagami M, Yokoyama Y, Mizunuma H. Presentation of a patient with pT2bN1M0 small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix who obtained long-term survival with maintenance chemotherapy, and literature-based discussion. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2011;32:99–102.

Lee DY, Chong C, Lee M, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Park SY. Prognostic factors in neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016;59:116–22. https://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2016.59.2.116.

Lewandowski GS, Copeland LJ. A potential role for intensive chemotherapy in the treatment of small cell neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;48:127–31. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.1993.1021.

Lyons YA, Frumovitz M, Soliman PT. Response to MEK inhibitor in small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix with a KRAS mutation. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2014;10:28–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gore.2014.09.003.

Margolis B, Tergas AI, Chen L, Hou JY, Burke WM, Hu JC, et al. Natural history and outcome of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:247–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.02.008.

McCann GA, Boutsicaris CE, Preston MM, Backes FJ, Eisenhauer EL, Fowler JM, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: the role of multimodality therapy in early-stage disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:135–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.01.014.

Murakami R, Kou I, Date K, Nakayama H. Advanced composite of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma: a case report of uterine cervical cancer in a virgin woman. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:921384. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/921384.

Omori M, Hashi A, Kondo T, Tagaya H, Hirata S. Successful neoadjuvant chemotherapy for large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep. 2014;8:4–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gynor.2013.12.001.

Paraghamian SE, Longoria TC, Eskander RN. Metastatic small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix treated with the PD-1 inhibitor, nivolumab: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40661-017-0038-9.

Peng P, Ming W, Jiaxin Y, Keng S. Neuroendocrine tumor of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:1247–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2407-2.

Rajkumar S, Iyer R, Culora G, Lane G. Fertility sparing management of large cell neuroendocrine tumour of cervix: a case report & review of literature. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;18:15–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gore.2016.10.002.

Sheth S, Shende D, Arneja S. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of cervix and leiomyoma between the vagina and rectum. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35:314–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2014.940295.

Stecklein SR, Jhingran A, Burzawa J, Ramalingam P, Klopp AH, Eifel PJ, Frumovitz M. Patterns of recurrence and survival in neuroendocrine cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:552–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.09.011.

Tanimoto H, Hamasaki A, Akimoto Y, Honda H, Takao Y, Okamoto K, et al. A case of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) of the uterine cervix successfully treated by postoperative CPT-11+CDDP chemotherapy after non-curative surgery. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2012;39:1439–41.

Wang PH, Liu YC, Lai CR, Chao HT, Yuan CC, Small YKJ. Cell carcinoma of the cervix: analysis of clinical and pathological findings. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1998;19:189–92.

Wang Q, Liu Y-H, Xie L, Hu W-J, Liu B-R. Small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix in pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:91–5. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2668.

Wang Z, Wu L, Yao H, Sun Y, Li X, Li B, et al. Clinical analysis of 32 cases with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix in early-stage disease. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2015;50:198–203.

Xie S, Song L, Yang F, Tang C, Yang S, He J, Pan X. Enhanced efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy in selected cases of surgically resected neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6361. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006361.

Zivanovic O, Leitao MM, Park KJ, Zhao H, Diaz JP, Konner J, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: analysis of outcome, recurrence pattern and the impact of platinum-based combination chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.010.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the DFG Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CBT and GAR collected the data. GAR analyzed the data. CBT, ZH, AD, and BS wrote the manuscript. PK, IT, and GAR critically contributed to the manuscript text. IT provided the data shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Immunohistochemical stainings of a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining. (B) Staining for CD56 (N-CAM). (C) Staining for the proliferation marker Ki-67 (using monoclonal antibody MIB-1). Bars, 100 μm. (PDF 1545 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tempfer, C.B., Tischoff, I., Dogan, A. et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Cancer 18, 530 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4447-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4447-x