Abstract

Background

The methylation status of oxygen 6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter has been associated with treatment response in glioblastoma(GBM). Using pre-operative MRI techniques to predict MGMT promoter methylation status remains inconclusive. In this study, we investigated the value of features from structural and advanced imagings in predicting the methylation of MGMT promoter in primary glioblastoma patients.

Methods

Ninety-two pathologically confirmed primary glioblastoma patients underwent preoperative structural MR imagings and the efficacy of structural image features were qualitatively analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. In addition, 77 of the 92 patients underwent additional advanced MRI scans including diffusion-weighted (DWI) and 3-diminsional pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (3D pCASL) imaging. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) values within the manually drawn region-of-interest (ROI) were calculated and compared using independent sample t test for their efficacies in predicting MGMT promoter methylation. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis was used to investigate the predicting efficacy with the area under the curve (AUC) and cross validations. Multiple-variable logistic regression model was employed to evaluate the predicting performance of multiple variables.

Results

MGMT promoter methylation was associated with tumor location and necrosis (P < 0.05). Significantly increased ADC value (P < 0.001) and decreased rCBF (P < 0.001) were associated with MGMT promoter methylation in primary glioblastoma. The ADC achieved the better predicting efficacy than rCBF (ADC: AUC, 0.860; sensitivity, 81.1%; specificity, 82.5%; vs rCBF: AUC, 0.835; sensitivity, 75.0%; specificity, 78.4%; P = 0.032). The combination of tumor location, necrosis, ADC and rCBF resulted in the highest AUC of 0.914.

Conclusion

ADC and rCBF are promising imaging biomarkers in clinical routine to predict the MGMT promoter methylation in primary glioblastoma patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Glioblastoma (GBM) [1], the most common primary malignant brain tumor, accounts for 45% of all malignant primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors and arises most commonly de novo (primary GBM) [2]. Despite multimodal treatments including invasive surgery followed by conformal radiation and chemotherapy, the patients’ median survival remains poor, ranging from 12 to 15 months [3, 4]. The clinical outcome of GBM patients depends on many factors, including age at diagnosis, Karnofsky score, tumor resection extent, the histological classification, tumor grade and genetic alterations of key molecules.

Recently, with the development of molecular pathology, the IDH1/2 gene mutations and oxygen 6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation are increasingly used as prognostic or predictive biomarkers for gliomas [5]. IDH status plays an important role in predicting patients’ survival, however, its mutation occurs in only 6% of GBM patients, leaving the vast majority of GBMs be IDH1/2 wild-type. Therefore, IDH mutation could not fully explain the GBM heterogeneity. MGMT inhibits the repair of temozolomide (TMZ)-induced therapeutic DNA damage, and ultimately correlates with progress-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of GBM patients [6]. Besides, the clinical practice offered evidence that MGMT promoter methylation plays important role in determining therapeutic strategies [7] and associates with better treatment response to TMZ [8]. Thus, it is very important to preoperatively identify the methylation status of MGMT promoter in GBM patients.

The gold standard to identify genetic alterations in GBM is surgical sampling, an necessary invasive procedure for GBM treatment or identification, however, may induce severe complications. Furthermore, GBM heterogeneity and sampling errors increase the risk of erroneous genetic profiling. In contrast, MRI, as a noninvasive method, appears to be an alternative to determine GBM MGMT promoter methylation.

To date, conventional structural image features, including tumor location, tumor volume, enhancement, invasiveness, and edema, have been utilized to predict the MGMT promoter methylation, however without expert consensus [9,10,11]. Recently, image texture analysis [12] and machine learning [13] based on these conventional MRI are gaining more attention, while the time-consuming methodology is not suitable for routine clinical work. Advanced MRI including dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) perfusion imaging [14,15,16,17], diffusion-weighted (DWI) [18,19,20] or diffusion tensor (DTI) imaging [17], arterial spin labeling (ASL) imaging [21] and CT imaging [17], are employed to predict MGMT promoter methylation with unsatisfying accuracies. However, both IDH mutant and wild-type GBMs were included in these studies [9,10,11, 14,15,16,16,16,16,16,16,22], without taking the varied image features or survivals between these two populations into consideration. The association between image parameters and MGMT promoter methylation is not clear, especially in IDH-wild-type GBM population.

Thus, we restricted the current analysis in GBM patients with wild-type IDH. The purpose of our study was to seek certain variables derived from conventional structural image features including multifocal, tumor cross midline, tumor location, enhancement, cyst, necrosis, edema, side, which may reflect MGMT promoter methylation status. Meanwhile, we evaluated the efficacy of ADC and rCBF values in predicting MGMT promoter methylation.

Methods

Patient population

One hundred and five patients with pathologically confirmed primary GBM from July 2014 to September 2015 were retrospectively investigated in the current study. All patients underwent near total or gross total resection. Patients were included according to the following criteria: (a) confirmative information of MGMT promoter methylation status, (b) the image quality was satisfying without susceptibility or motion artifacts, (c) receiving no corticosteroid when MRI was performed, and (d) presence of solid tumor components available for ADC analysis.

Five patients without IDH information and 8 with IDH mutation were excluded, leaving 92 enrolled patients in the current study. Nine patients without 3D pCASL and 6 without DWI were excluded. The final study population contained 77 patients (36 men and 41 women; mean age, 55 years; age, 21–87 years) with newly diagnosed and pathologically confirmed GBM with wild-type IDH. The process flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

MRI data acquisition

The whole brain MRI examinations were performed on a 3 T MRI system (Discovery MR750, General Electric Medical System, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with an eight-channel head coil (General Electric Medical System). Conventional MRI, contrast-enhanced MRI, DWI and 3D pCASL imaging were implemented during the examination.

Conventional MRI sequences included axial T1w image (TR/TE, 1750 ms/24 ms; matrix size, 256 × 256; FOV, 24 × 24 cm; number of excitation, 1; slice thickness, 5 mm; gap, 1.5 mm), axial T2w image (TR/TE, 4247 ms/93 ms; matrix size, 512 × 512; FOV, 24 × 24 cm; number of excitation, 1; slice thickness, 5 mm; gap, 1.5 mm) and sagittal T2w image (TR/TE, 10,639 ms/96 ms; matrix size, 384 × 384; FOV, 24 × 24 cm; number of excitation, 2; slice thickness, 5 mm; gap, 1.0 mm), and axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (TR/TE, 8000 ms/165 ms; matrix size, 256 × 256; FOV, 24 × 24 cm; number of excitation, 1; slice thickness, 5 mm; gap, 1.5 mm). DWI was obtained using a single-shot, echo-planar sequence in the axial plane (TR/TE, 3000 ms/minimum ms; FOV, 24 × 24 cm; matrix size, 160 × 160; number of excitation, 2; slice thickness, 5 mm; gap, 1.5 mm). Two b values (0 and 1000 s/mm2) were used in three orthogonal directions. The acquisition time for DWI was 24 s. 3D pCASL was acquired prior to the injection of contrast agents, using a 3D spiral fast spin echo (FSE) sequence (TR/TE, 4590 ms/10.5 ms; FOV, 24 × 24 cm; slice thickness, 4 mm; slice number, 40; number of excitation, 3; and post-labeling delay time, 1525 ms).

Finally, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted spin echo sequence was acquired in the transverse, sagittal, and coronal planes after intravenous administration of 0.1 mmol/kg gadodiamide (Omniscan; GE Healthcare, Co. Cork, Ireland). 3D T1-weighted sequences were also acquired (TR/TE, 8.2 ms/3.2 ms; TI, 450 ms; flip angle 12°; section thickness, 1.2 mm; FOV, 512 × 512 mm; matrix size, 256 × 256; number of excitations, 1; image number, 140).

MRI data processing and image analysis

All data were transferred to a workstation (Advantage Workstation 4.6, General Electric Medical System, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) for processing.

The conventional structural image features of all patients were assessed independently by two experienced neuroradiologists (Y.-C.H. and L.-F.Y. who have 12 and 6 years of experience, respectively, in neuro-oncology imaging) who were blinded to the MGMT promoter methylation status. A third senior neuroradiologist (G.-B.C, 25 years of experience in brain tumor diagnosis) re-examined the images and determined the final classification of image feature when inconsistency existed between the two neuroradologists. Tumor features derived from the MRI were characterized based on the criteria outlined in Table 1.

First, the two radiologists independently reviewed the conventional plain and contrast-enhanced MR images carefully to determine the solid part of tumor before ADC and CBF analyses. Next, a region of interest (ROI) was manually drawn on the solid part of the tumor with relatively higher signal on DWI and lower ADC value in ADC map. Similarly, ROI was drawn to include the solid elements of tumor with relatively higher signal on CBF map by using 3D contrast enhanced T1weighted imaging(3D–T1WI/C) as cross-reference. The mean ROI area of the lesions was 55.7 ± 6.3 mm2 (range, 41.0–73.0 mm2). Meanwhile, for both the ADC and 3D pCASL analyses, hemorrhagic, calcified, cystic, necrotic areas and large vessels were avoided. Each radiologist made three ROIs on the lesion side, and the mean value was calculated as the final value. To conduct the normalization, CBF value on the lesion side was normalized to that on the contralateral side with same size ROI: rCBF = CBF value on the lesion side/CBF value on the contralateral side.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and WEKA software (WEKA version 3.8.1). A P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistical significance.

Analyses of conventional structural image features. - Categorical data of conventional structural image features (location, tumor cross midline, multifocal, necrosis, edema, cyst, enhancement and side) between MGMT promoter methylated group and unmethylated group were analyzed using the Fisher’s exact test.

Diagnostic performance with ADC or rCBF. - Quantitative data (ADC value and rCBF) were denoted as the mean and standard deviation. The normal distribution of data was investigated with Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test. The differences of ADC and rCBF values between MGMT promoter methylated and unmethylated groups were analyzed by using independent sample t test. ROC analyses were performed to determine the efficacies (sensitivity, specificity, and AUC) of different parameters in predicting MGMT promoter methylation. The Youden index was employed to identify the optimal cut-off value. Additionally, leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) was used to prevent over-fitting, and validated AUC was obtained as well.

Efficacies of imaging parameter combinations. - A multivariate logistic regression model (LRM) with LOOCV was used to investigate the efficacies of image parameter combinations in predicting MGMT promoter methylation.

Analysis of agreement. - The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis was used to assess the inter-reader agreement on measuring image parameters. The ICC was interpreted as poor (< 0.4), moderate (≥ 0.4 but < 0.75), and good (> 0.75).

Results

Differences in conventional structural image features between MGMT promoter methylated and unmethylated groups

The conventional structural image features of the 92 GBM patients were summarized in Table 2. Tumor location was significantly different between MGMT promoter methylated and unmethylated groups (P = 0.012), implying that the subventricular zone (SVZ) was more likely to be spared in patients with MGMT promoter methylation. Besides, MGMT promoter methylation is prone to be associated with tumor necrosis (P = 0.028). Other qualitative image features were not significantly different between these two groups, including multifocal (P = 0.114), tumor cross midline (P = 0.478), cyst (P = 0.335), edema (P = 0.688), enhancement (P = 0.259) and side (P = 0.720).

Performance of single advanced MRI parameter (ADC and rCBF) in predicting MGMT promoter methylation

The descriptive statistics of the DWI and 3D pCASL parameters between MGMT promoter methylated and unmethylated groups were shown in Table 3. The rCBF of GBMs with unmethylated MGMT promoter (9.467 ± 2.706, n = 40) was significantly higher than that of the methylated group (5.916 ± 2.518, n = 37) (P < 0.001). The ADC value was lower in MGMT promoter unmethylated group (0.729 ± 0.085 × 10− 3 mm2/s, n = 40) than that of the methylated group (0.889 ± 0.137 × 10− 3 mm2/s, n = 37) (P < 0.001). The representative cases were shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

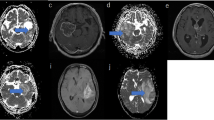

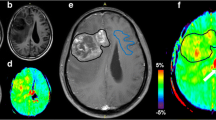

Structural (a, b, c and d) and advanced (e, f, g and h) MR images obtained from a 53-year-old female showing left frontal lobe GBM with MGMT promoter methylation. a Precontrast T1-weighted image. b Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image. c T2-weighted image. d Postcontrast T1-weighted image. e DWI map. f ADC map: the mean ADC value of the three small ROI was 0.722 × 10− 3 mm2/s. g The map fused CBF and 3D–T1WI/C. h CBF map: the mean rCBF of the three small ROI was 3.94

Structural (a, b, c and d) and advanced (e, f, g and h) MR images obtained from a 55-year-old male showing right temporal and parietal lobe GBM without MGMT promoter methylation. a Precontrast T1-weighted image. b Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image. c T2-weighted image. d Postcontrast T1-weighted image. e DWI map. f ADC map: the mean ADC value of the three small ROI was 0.661 × 10− 3 mm2/s. g The map fused CBF and 3D–T1WI/C. h CBF map: the mean rCBF of the three small ROI was 10.64

In predicting MGMT promoter methylation, the AUC of the ADC (0.860) was higher than that of the rCBF (0.835). The optimal thresholds for predicting MGMT promoter methylation were 0.792 × 10− 3 mm2/s for ADC and 7.680 for rCBF (Table 4). By using LOOCV, the cross-validated AUC and accuracy were 0.842 and 79.2% for ADC and 0.814 and 74.0% for rCBF, respectively (Table 4).

Efficacies of parameter combinations for predicting MGMT promoter methylation

On ROC analyses, the AUC for predicting MGMT promoter methylation was the highest when location, necrosis, ADC and rCBF (0.914) were combined, and the lowest when location and necrosis (0.670) were combined (Table 5). For differentiating MGMT promoter methylation from unmethylation, the addition of ADC or rCBF to the combination of location and necrosis significantly improved the AUC from 0.670 to 0.891 (when ADC was added) and from 0.670 to 0.852 (when rCBF was added), respectively.

Compared to combination of location, necrosis and ADC/rCBF, LOOCV offered evidence that the combination of ADC and rCBF showed the higher diagnostic accuracy for distinguishing MGMT promoter methylation from unmethylation. Compared with combination of ADC and rCBF, the addition of location and necrosis did not significantly improved cross-validated AUC. The cross-validated accuracy were 81.8% (for the combination of ADC and rCBF) and 80.5% (for the combination of location, necrosis, ADC and rCBF) (Table 5). The results of the ROC analyses and cross-validations for the combined imaging parameters were summarized in Table 5, respectively.

Analysis of agreement

As shown in Table 6, the inter-observer ICC value for ADC and rCBF was close to 1 (P < 0.001), suggesting excellent measurement reliability of quantitative MRI parameters.

Discussion

In the present study, we revealed that the methylation status of the MGMT promoter in IDH-wild-type GBM was associated with conventional structural image features (tumor location and necrosis). Moreover, the diagnostic performance of ADC was found to be slightly better than that of rCBF in predicting MGMT promoter methylation. In addition, the integrative performance of combined structural image features (location and necrosis) and quantitative parameters (ADC and rCBF) achieved the highest AUC, compared to the combination of location and necrosis or ADC/rCBF.

In the current study, among all the investigated conventional structural image features, only tumor location and necrosis were correlated with MGMT promoter methylation status. First, GBMs with methylated MGMT promoter were more frequently associated with severe necrosis. This result is inconsistent with previous report [23]. One possible explanation may be that methylation of the MGMT promoter decreases the MGMT protein level. As a DNA repair enzyme, decreased MGMT led to severe DNA damage and cell death, eventually more necrosis in tumor. Second, our result demonstrated that SVZ was more likely to be spared in patients with MGMT promoter methylation. Previous studies suggested that MGMT promoter methylation is associated with GBM in parietal and occipital lobes [23], the left hemisphere and temporal lobe [10] or independent from tumor location [13]. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing the relationship between involvement of SVZ and MGMT promoter methylation in GBMs population with wild-type IDH. It is now generally accepted that tumor location, as an important image feature [24] associated with genetic features, is closely related with patient prognosis [25]. Our findings may help explain why MGMT promoter methylated GBMs, which spare the SVZ, have prolonged survival. However, since type I-II contacting the SVZ may be skewed in large tumors, and is not necessarily the same as the SVZ arising ones with the center in the SVZ, cautions should be paid when dealing with such cases and further studies are needed to clarify this issue.

ADC [25, 26] was used as a potential surrogate biomarker for MGMT promoter methylation, however, with controversies [15,16,17,18,19,20, 22, 27, 28]. In our study, we revealed that the ADC value in GBMs with MGMT promoter methylation was higher than in those without MGMT promoter methylation. In accordance with our results, several previous studies showed that ADC ratios or ADC minimum values were lower in tumors with unmethylated MGMT promoters than with methylated promoters [17, 18] and that mean ADC had a positive relationship with the MGMT promoter methylation ratio [22]. However, lower ADC value in MGMT promoter methylated GBMs was reported in a recent histogram analysis study [27]. Besides, no significant correlation between ADC values and MGMT promoter methylation status was also reported [20, 28]. These conflicting results may be partially attributed to different methodologies, including ROI selection (only contrast enhanced portion of the tumor), and different cohorts (high-grade glioma, versus GBMs only). This study is different from previous ones in the study population (IDH-wild-type GBMs only versus both IDH mutant and IDH-wild-type GBMs [15,16,17,18,19,20, 28]) and ROI (ADC minimum area of tumor solid part, not simply contrast enhanced portion of the tumor [29]), which may explain the difference between ours and previous ones. Further investigation with a larger cohort and unified protocol is needed.

3D pCASL, providing valuable information about tumor angiogenesis, can be an important biological marker for tumor grading [30] and treatment response predicting [31]. However, to our knowledge, no significant correlation between rCBF and MGMT promoter methylation was reported in only one study [21]. However, a major confounding factor in that study is the fact that both IDH mutant and IDH-wild-type GBMs were included, with a relatively small number of patients in each group for MGMT promoter methylation analysis. Here, significant differences in the rCBF between MGMT promoter methylated and unmethylated GBMs was confirmed in the current study. A recent study [32] showed a direct link between MGMT expression and decreased angiogenesis of GBM cells, with the unclear mechanism. Therefore, the rCBF provided by 3D pCASL may be a potential image parameter to predict the MGMT promoter methylation. Taking together, both ADC and rCBF performed well in their standing alone ability to predict MGMT promoter methylation in this study. It is generally accepted that varied functional MR techniques can provide different valuable information about tumor microenvironment, which makes the combinational utilization of multimodal MRIs necessary. Our study indeed demonstrated that combination of ADC and rCBF improved the performance in predicting MGMT promoter methylation over single modality parameter. Adding advanced modality parameters (ADC or rCBF) to conventional ones (tumor location and necrosis) further improved the diagnostic accuracy. Given that neither rCBF nor ADC requires an exogenous contrast agent, our results imply that ADC and rCBF is especially useful as an adjunct for predicting MGMT promoter methylation when the patients’ condition is not appropriate for contrast agent administration.

There are some limitations for the current study. First, the sample size was relatively small. Second, analysis of patients’ overall survival and the match of surgical specimen with the corresponding image were not performed. Third, although the measurement consistency between the two independent radiologists was good, however, possible bias still existed due to the manual drawing and/or visually positioning ROIs.

Conclusions

The methylation status of the MGMT promoter in IDH-wild-type GBM was associated with conventional structural image features (tumor location and necrosis). ADC peroformed slightly better than rCBF in predicting MGMT promoter methylation. Combining structural image features (location and necrosis) and quantitative parameters (ADC and rCBF) achieved the higher AUC.

Abbreviations

- 3DpCASL:

-

3-diminsional pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling

- ADC:

-

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- ASL:

-

Arterial spin labeling

- CBF:

-

Cerebral blood flow

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- DSC:

-

Dynamic susceptibility contrast

- DTI:

-

Diffusion tensor imaging

- DWI:

-

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- GBM:

-

Glioblastoma

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation coefficien

- LOOCV:

-

Leave-one-out cross-validation

- LRM:

-

Logistic regression model

- MGMT:

-

Oxygen 6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase

- PFS:

-

Progress-free survival

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- SVZ:

-

Subventricular zone

- TMZ:

-

Temozolomide

Reference

Omuro A, DeAngelis LM. Glioblastoma and other malignant gliomas: a clinical review. JAMA. 2013;310(17):1842–50.

Karsy M, Huang T, Kleinman G, Karpel-Massler G. Molecular, histopathological, and genomic variants of glioblastoma. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2014;19:1065–87.

Oh J, Henry RG, Pirzkall A, Lu Y, Li X, Catalaa I, Chang S, Dillon WP, Nelson SJ. Survival analysis in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: predictive value of choline-to-N-acetylaspartate index, apparent diffusion coefficient, and relative cerebral blood volume. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19(5):546–54.

Marijnen CA, van den Berg SM, van Duinen SG, Voormolen JH, Noordijk EM. Radiotherapy is effective in patients with glioblastoma multiforme with a limited prognosis and in patients above 70 years of age: a retrospective single institution analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2005;75(2):210–6.

Roszkowski K, Furtak J, Zurawski B, Szylberg T, Lewandowska MA. Potential role of methylation marker in glioma supporting clinical decisions. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(11).

Dunn J, Baborie A, Alam F, Joyce K, Moxham M, Sibson R, Crooks D, Husband D, Shenoy A, Brodbelt A, et al. Extent of MGMT promoter methylation correlates with outcome in glioblastomas given temozolomide and radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(1):124–31.

Jiang T, Mao Y, Ma W, Mao Q, You Y, Yang X, Jiang C, Kang C, Li X, Chen L, et al. CGCG clinical practice guidelines for the management of adult diffuse gliomas. Cancer Lett. 2016;375(2):263–73.

Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, Kros JM, Hainfellner JA, Mason W, Mariani L, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003.

Drabycz S, Roldan G, de Robles P, Adler D, McIntyre JB, Magliocco AM, Cairncross JG, Mitchell JR. An analysis of image texture, tumor location, and MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma using magnetic resonance imaging. NeuroImage. 2010;49(2):1398–405.

Ellingson BM, Cloughesy TF, Pope WB, Zaw TM, Phillips H, Lalezari S, Nghiemphu PL, Ibrahim H, Naeini KM, Harris RJ, et al. Anatomic localization of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylated and unmethylated tumors: a radiographic study in 358 de novo human glioblastomas. NeuroImage. 2012;59(2):908–16.

Kanas VG, Zacharaki EI, Thomas GA, Zinn PO, Megalooikonomou V, Colen RR. Learning MRI-based classification models for MGMT methylation status prediction in glioblastoma. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2017;140:249–57.

Korfiatis P, Kline TL, Coufalova L, Lachance DH, Parney IF, Carter RE, Buckner JC, Erickson BJ. MRI texture features as biomarkers to predict MGMT methylation status in glioblastomas. Med Phys. 2016;43(6):2835.

Kickingereder P, Bonekamp D, Nowosielski M, Kratz A, Sill M, Burth S, Wick A, Eidel O, Schlemmer HP, Radbruch A, et al. Radiogenomics of glioblastoma: machine learning-based classification of molecular characteristics by using multiparametric and multiregional MR imaging features. Radiology. 2016;281(3):907–18.

Ryoo I, Choi SH, Kim JH, Sohn CH, Kim SC, Shin HS, Yeom JA, Jung SC, Lee AL, Yun TJ, et al. Cerebral blood volume calculated by dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging: preliminary correlation study with glioblastoma genetic profiles. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71704.

Ahn SS, Shin NY, Chang JH, Kim SH, Kim EH, Kim DW, Lee SK. Prediction of methylguanine methyltransferase promoter methylation in glioblastoma using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance and diffusion tensor imaging. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(2):367–73.

Gupta A, Omuro AM, Shah AD, Graber JJ, Shi W, Zhang Z, Young RJ. Continuing the search for MR imaging biomarkers for MGMT promoter methylation status: conventional and perfusion MRI revisited. Neuroradiology. 2012;54(6):641–3.

Moon WJ, Choi JW, Roh HG, Lim SD, Koh YC. Imaging parameters of high grade gliomas in relation to the MGMT promoter methylation status: the CT, diffusion tensor imaging, and perfusion MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 2012;54(6):555–63.

Romano A, Calabria LF, Tavanti F, Minniti G, Rossi-Espagnet MC, Coppola V, Pugliese S, Guida D, Francione G, Colonnese C, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient obtained by magnetic resonance imaging as a prognostic marker in glioblastomas: correlation with MGMT promoter methylation status. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(2):513–20.

Rundle-Thiele D, Day B, Stringer B, Fay M, Martin J, Jeffree RL, Thomas P, Bell C, Salvado O, Gal Y, et al. Using the apparent diffusion coefficient to identifying MGMT promoter methylation status early in glioblastoma: importance of analytical method. J Med Radiat Sci. 2015;62(2):92–8.

Choi YS, Ahn SS, Kim DW, Chang JH, Kang SG, Kim EH, Kim SH, Rim TH, Lee SK. Incremental prognostic value of ADC histogram analysis over MGMT promoter methylation status in patients with glioblastoma. Radiology. 2016;281(1):175–84.

Yamashita K, Hiwatashi A, Togao O, Kikuchi K, Hatae R, Yoshimoto K, Mizoguchi M, Suzuki SO, Yoshiura T, Honda H. MR imaging-based analysis of glioblastoma Multiforme: estimation of IDH1 mutation status. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(1):58–65.

Sunwoo L, Choi SH, Park CK, Kim JW, Yi KS, Lee WJ, Yoon TJ, Song SW, Kim JE, Kim JY, et al. Correlation of apparent diffusion coefficient values measured by diffusion MRI and MGMT promoter methylation semiquantitatively analyzed with MS-MLPA in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37(2):351–8.

Eoli M, Menghi F, Bruzzone MG, De Simone T, Valletta L, Pollo B, Bissola L, Silvani A, Bianchessi D, D'Incerti L, et al. Methylation of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase and loss of heterozygosity on 19q and/or 17p are overlapping features of secondary glioblastomas with prolonged survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(9):2606–13.

Lim DA, Cha S, Mayo MC, Chen MH, Keles E, VandenBerg S, Berger MS. Relationship of glioblastoma multiforme to neural stem cell regions predicts invasive and multifocal tumor phenotype. Neuro-Oncology. 2007;9(4):424–9.

Hu YC, Yan LF, Sun Q, Liu ZC, Wang SM, Han Y, Tian Q, Sun YZ, Zheng DD, Wang W, et al. Comparison between ultra-high and conventional mono b-value DWI for preoperative glioma grading. Oncotarget. 2017;8(23):37884–895.

Zhang L, Min Z, Tang M, Chen S, Lei X, Zhang X. The utility of diffusion MRI with quantitative ADC measurements for differentiating high-grade from low-grade cerebral gliomas: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2017;373:9–15.

Pope WB, Lai A, Mehta R, Kim HJ, Qiao J, Young JR, Xue X, Goldin J, Brown MS, Nghiemphu PL, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient histogram analysis stratifies progression-free survival in newly diagnosed bevacizumab-treated glioblastoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(5):882–9.

Gupta A, Prager A, Young RJ, Shi W, Omuro AM, Graber JJ. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging and MGMT methylation status in glioblastoma: a reappraisal of the role of preoperative quantitative ADC measurements. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(1):E10–1.

Eidel O, Burth S, Neumann JO, Kieslich PJ, Sahm F, Jungk C, Kickingereder P, Bickelhaupt S, Mundiyanapurath S, Baumer P, et al. Tumor infiltration in enhancing and non-enhancing parts of glioblastoma: a correlation with histopathology. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169292.

Roy B, Awasthi R, Bindal A, Sahoo P, Kumar R, Behari S, Ojha BK, Husain N, Pandey CM, Rathore RK, et al. Comparative evaluation of 3-dimensional pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling with dynamic contrast-enhanced perfusion magnetic resonance imaging in grading of human glioma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2013;37(3):321–6.

Haller S, Zaharchuk G, Thomas DL, Lovblad KO, Barkhof F, Golay X. Arterial spin labeling perfusion of the brain: emerging clinical applications. Radiology. 2016;281(2):337–56.

Chahal M, Xu Y, Lesniak D, Graham K, Famulski K, Christensen JG, Aghi M, Jacques A, Murray D, Sabri S, et al. MGMT modulates glioblastoma angiogenesis and response to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12(8):822–33.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. W XC in GE Healthcare China for providing technical support regarding the appropriate applied DWI and 3D pCASL sequence.

Funding

This study received financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2008 K13–04 to Dr. Cui GB), Science and Technology Development of Shaanxi Province (No. 2014JZ2–007 to Dr. Cui GB) and Innovation and Development Foundation of Tangdu Hospital (No. 2016LCYJ001 to Dr. Cui GB).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CGB and WW conceived the project, HY, YLF, SYZ conducted the patient enrollment and data collection, WXB, ZX, LZC, NHY, HYC, YY (Yang Yang) and ZJ contributed to the data analysis and graph making, YY (Ying Yu), SQ, TQ, HB and XG contributed to the thoughtful discussion and constructive help in data analysis. HY, WW, YLF and CGB drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received ethics approval from the ethic committed of Tangdu Hospital and the informed consents were waived from all participants. This study was also registered to ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02622620, https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Y., Yan, LF., Wang, XB. et al. Structural and advanced imaging in predicting MGMT promoter methylation of primary glioblastoma: a region of interest based analysis. BMC Cancer 18, 215 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4114-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4114-2