Abstract

Background

Methylation is a common epigenetic modification which may play a crucial role in cancer development. To investigate the association between methylation of COX-2 in blood leukocyte DNA and risk of gastric cancer (GC), a nested case–control study was conducted in Linqu County, Shandong Province, a high risk area of GC in China.

Methods

Association between blood leukocyte DNA methylation of COX-2 and risk of GC was investigated in 133 GCs and 285 superficial gastritis (SG)/ chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG). The temporal trend of COX-2 methylation level during GC development was further explored in 74 pre-GC and 95 post-GC samples (including 31 cases with both pre- and post-GC samples). In addition, the association of DNA methylation and risk of progression to GC was evaluated in 74 pre-GC samples and their relevant intestinal metaplasia (IM)/dysplasia (DYS) controls. Methylation level was determined by quantitative methylation-specific PCR (QMSP). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by unconditional logistic regression analysis.

Results

The medians of COX-2 methylation levels were 2.3 % and 2.2 % in GC cases and controls, respectively. No significant association was found between COX-2 methylation and risk of GC (OR, 1.15; 95 % CI: 0.70-1.88). However, the temporal trend analysis showed that COX-2 methylation levels were elevated at 1–4 years ahead of clinical GC diagnosis compared with the year of GC diagnosis (3.0 % vs. 2.2 %, p = 0.01). Further validation in 31 GCs with both pre- and post-GC samples indicated that COX-2 methylation levels were significantly decreased at the year of GC diagnosis compared with pre-GC samples (1.5 % vs. 2.5 %, p = 0.02). No significant association between COX-2 methylation and risk of progression to GC was found in subjects with IM (OR, 0.50; 95 % CI: 0.18–1.42) or DYS (OR, 0.70; 95 % CI: 0.23–2.18). Additionally, we found that elder people had increased risk of COX-2 hypermethylation (OR, 1.55; 95 % CI: 1.02–2.36) and subjects who ever infected with H. pylori had decreased risk of COX-2 hypermethylation (OR, 0.54; 95 % CI: 0.34–0.88).

Conclusions

COX-2 methylation exists in blood leukocyte DNA but at a low level. COX-2 methylation levels in blood leukocyte DNA may change during GC development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. Evidences accumulatively revealed that GC was a consequence of multistage progression of gastric lesions with complex molecular alterations, including DNA methylation [2–4].

Several tumor-related genes, such as CDH1, p16, APC, COX-2, RUNX3, and hMLH1, were detected aberrant methylation in GC [5–8]. However, most of these studies were focused on tissue samples, and few data on the alteration of blood leukocyte DNA methylation was reported. Unlike tissue DNA, blood leukocyte DNA can be obtained non-invasively and inexpensively, thus, aberrant methylation of blood leukocyte DNA may serve as a potential biomarker for GC diagnosis.

Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) is an inducible enzyme, and particularly overexpressed during inflammation of tissue [9]. Animal models showed that COX-2 played important roles in cell adhesion, apoptosis, and angiogenesis [10]. Recently, COX-2 was found to be up-regulated in various carcinomas and play a central role in tumorigenesis [11–13]. Our previous study demonstrated that overexpression of COX-2 was associated with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and increased the risk of precancerous gastric lesions [14]. Studies in vitro and in tumor tissue suggested that promoter methylation status of COX-2 may regulate mRNA and protein expression [8, 15–17]. However, little is known about COX-2 promoter methylation status in blood leukocyte DNA.

In this study, we were particularly interested in the association between COX-2 methylation in blood leukocyte DNA and risk of GC. We compared the COX-2 methylation levels in GC cases with superficial gastritis (SG) or mild chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) controls. In addition, blood samples collected before or/and after GC clinical diagnosis from two long-term cohorts provided us a unique opportunity to evaluate the dynamic changes of COX-2 methylation levels during progression of gastric lesions and GC development.

Methods

Study population

In 1989 and 2002, two cohort studies were launched in Linqu County, involving 3433 and 2638 subjects [18, 19], and 186 GCs were identified until 2009. Endoscopic screening was performed at baseline of each cohort and followed a repeated endoscopic examination using the same procedures in 1999, 2003 and 2009, respectively. For each subject, the biopsy specimens were taken from 5–7 standard sites of the stomach, and given its corresponding histopathologic diagnosis by three senior pathologists independently from Peking University Cancer Hospital according to the Updated Sydney System [20] and Padova International Classification [21]. Each biopsy was classified according to the presence or absence of SG, mild/severe CAG, intestinal metaplasia (IM), dysplasia (DYS) or GC, and given a diagnosis based on the most severe histology. Each subject was assigned a “global” diagnosis based on the most severe diagnosis among any of the biopsies.

For the current study, a nested case–control design was used based on the two cohorts enrolling 133 GC cases with at least one blood sample from follow-up period. According to the time of diagnosis, blood leukocyte samples collected from GC cases were defined into pre-GC (before GC diagnosis ranging from 1 to 10 years) and post-GC (the year of GC diagnosis or up to 10 years after). Among them, 74 pre-GC blood samples from 69 GC cases (5 cases with two pre-GC samples with different time interval) and 95 post-GC samples were collected. Additionally, 31 cases had both pre-GC and post-GC samples were also selected as self-control to measure the methylation levels in the two time intervals (Fig. 1).

To test COX-2 methylation level and risk of GC, 285 subjects with SG or mild CAG were selected as controls for 95 post-GC cases at random with a ratio of 1:3 and frequency-matched in age category (<60 and ≥60 years) and gender. We further selected 99 subjects with IM and 105 with DYS who did not progress to GC during the follow-up period randomly from baseline as controls, because the corresponding gastric lesions for the pre-GC diagnosis were mainly IM (n = 33) and DYS (n = 35) (Fig. 1).

All of the blood samples were collected before the endoscopic examination. Information on gender, date of birth, cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking were obtained from the questionnaires at the baseline of the two cohorts, respectively. Age was determined according to the year when blood sample was collected. Because a number of repeated endoscopic examinations were performed, more than one blood samples from the same subject were collected. Consequently, different ages were calculated corresponding to the date of sample collection in the data analysis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University School of Oncology and all subjects gave written informed consent.

DNA preparation and bisulfite modification

Peripheral blood samples were collected in K2EDTA tubes (BD Vacutainer®) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min for separation from plasma. The leukocyte fraction was washed by Tris-EDTA for 3 times and high molecular weight genomic DNA was isolated by standard proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction. Bisulfite treatment was reported previously [22]. Briefly, 1–10 μg genomic DNA was modified with sodium bisulfite for 16 h at 50 °C to completely convert the unmethylated cytosines to uridines. Bisulfite treated DNA was then purified with a genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and stored at −20 °C until use.

COX-2 Methylation analysis

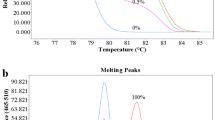

Fluorescence-based, real-time quantitative methylation-specific PCR (QMSP) was carried out for COX-2 using a 7500 fast Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the primers and probe as described previously [23]. The PCR was conducted in a 20-μl mixture, containing 100 ng of bisulfate modified DNA, 200nM of each primer and probe, and 10 μl 2X-MaximaTM Probe/Rox qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas Burlington, Ontario, Canada) at the following conditions: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. The efficiency of PCR amplification was confirmed to be nearly 100 %, and beta actin (ACTB) was used as a reference set to normalize for input DNA.

The methylation level of COX-2 was expressed as percentage, calculated by dividing the COX-2/ACTB ratio of a sample by the COX-2/ACTB ratio of HL60 (a human promyelocytic leukemia cell line which was confirmed to be 100 % methylated in the CpGs in COX-2 primers and probe). The analysis was performed blind by one technician, and various lesion groups were randomly mixed for bisulfite treatment and real-time PCR. Each primer pair was run in a separate well and at least 2 parallels were required at each sample. Parallels were removed when the CT values differed more than 0.06, and the same sample was repeated. A total unmethylated cell line MKN45 was used as negative control to qualify the PCR reaction as well as DNA preparation and bisulfite modification procedure.

H. pylori antibody assay

H. pylori antibody assays were used for determination of H. pylori infection with the serum separated from blood samples collected. Details of serologic assay were described previously [24]. Briefly, serum levels of anti-H. pylori IgG were measured separately in duplicate with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) procedures. An individual was determined to be positive for H. pylori infection if the mean optical density of IgG ≥ 1.0. Quality-control samples were assayed at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s χ2 test was used to examine the differences in distribution of age group, gender, smoking, drinking and H. pylori infection status between SG/CAG and post-GC groups. Mann–Whitney/Wilcoxon test was used to compare the COX-2 methylation levels between SG/CAG and post-GC groups.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were used to assess the associations between COX-2 methylation and the risk of GC and progression of gastric lesions, the potential risk factors, and the differences methylation levels between pre-GC and post-GC groups by unconditional logistic regression, adjusting for age, gender, smoking, drinking, and H. pylori infection status. Ptrend was applied by unconditional logistic regression to analyze the temporal trend of COX-2 methylation levels. To compare the methylation status in 31 GC cases with both pre- and post-diagnosis blood samples, conditional logistic regression was applied with age adjusted.

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System software (version 9.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P value of <0.05 was considered significant and all statistical tests were two sided.

Results

The frequency distributions of age, gender, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and H. pylori status of 95 post-GCs and 285 controls were presented in Table 1. The frequency of H. pylori infection was significantly higher in GC than control group (88.4 % vs. 61.4 %, p < 0.001). The other factors showed no statistical difference in the two groups.

Methylation levels in GCs and SG/CAG controls

We first compared the methylation levels of COX-2 between GC cases and SG/mild CAG controls. The medians (interquartile range) of COX-2 methylation levels were 2.3 % (1.2–3.9 %) in cases and 2.2 % (1.4–3.4 %) in controls (p = 0.94). To further evaluate the relationship between COX-2 methylation and risk of GC, we set 2 % as a cut-off value according to the median level in control group. No significant association was found between COX-2 methylation level and GC risk (OR, 1.15; 95 % CI: 0.70–1.88) after adjusting for age, gender, smoking, drinking and H. pylori infection.

Temporal trends of methylation levels in GC development

By comparing pre-GC (n = 74) and post-GC (n = 95) samples (Table 2), we found that COX-2 methylation levels were slightly lower in post-GC samples than pre-GC samples (2.3 % vs.2.5 %), although the p value showed no statistical significance (p = 0.32).

The temporal trend of COX-2 methylation levels during GC development was explored by dividing the pre- and post-GC samples into 5 groups (5–10 years pre-GC, 1–4 years pre-GC, GC diagnosis year, 1–4 years post-GC and 5–10 years post-GC) according to the time interval between sample collection and GC diagnosis. As shown in Table 2, the median methylation levels of COX-2 in different groups were 1.9 % (1.4–4.0 %), 3.0 % (2.0–4.5 %), 2.2 % (1.1–2.8 %), 1.9 % (1.4–2.9 %) and 2.8 % (1.8–4.9 %), respectively. Taking the year of GC diagnosis as reference (2.2 %), COX-2 methylation levels were significantly increased at 1–4 years ahead of clinical GC diagnosis (3.0 %, p = 0.01), and decreased at 1–4 years after GC diagnosis (1.9 %, p = 0.80). However, COX-2 methylation was back to a higher level at 5–10 years after GC diagnosis (2.8 %, p = 0.06). Since COX-2 methylation levels fluctuated before and after GC clinical diagnosis, we did not find a significance linear trend between groups (p = 0.32).

A similar trend of COX-2 methylation levels was further validated in 31 GC cases (10 females and 21 males) with both pre-GC and post-GC samples (Table 3). We found that COX-2 methylation levels were significantly decreased in post-GC compared with pre-GC samples (1.5 % vs. 2.5 %, p = 0.04). Because most of the 31 pairs of GC samples were collected at 1–4 years ahead of diagnosis (n = 22) and GC diagnosis year (n = 21), we compared two groups and found that COX-2 methylation levels were significantly lower in GC diagnosis year samples than in 1–4 years pre-GC samples (1.5 % vs.2.5 %, p = 0.02).

Methylation levels in IM or DYS subjects with different outcomes

Because the corresponding gastric lesions for the pre-GC diagnosis were mainly IM and DYS, we were very interested to compare the methylation levels in subjects with IM or DYS progressed or not progressed to GC during the follow-up period. However, no significant differences were found between subjects with IM/DYS progressed or not to GC (OR, 0.50; 95 % CI: 0.18–1.42 for IM and OR, 0.70; 95 % CI: 0.23–2.18 for DYS) (Table 4).

Relationships between methylation status and epidemiologic parameters

We also examined the association between COX-2 methylation level and age or other risk factors. As shown in Table 5, for the total participants, COX-2 methylation levels were significantly higher in older subjects (OR, 1.55; 95 % CI: 1.02–2.36), but lower in subject who ever infected with H. pylori (OR, 0.54; 95 % CI: 0.34–0.88). No statistically significant associations were observed between COX-2 methylation level and gender, smoking, and drinking.

Discussion

In the present study, based on our two cohort studies in a high-risk population of GC, we quantified COX-2 methylation level in blood leukocyte DNA of various gastric lesions and investigated the relationship between methylation of COX-2 in blood leukocyte DNA and risk of GC.

Until now, studies on the association between blood leukocyte DNA methylation and risk of GC are limited. Several studies suggested that global hypomethylation in blood leukocyte DNA may be related to GC risk [25, 26]. Recently, a study showed that whole blood p16 methylation may serve as an important prognostic indicator of gastric adenocarcinoma [27]. A Japanese study showed that methylation level of IGF2 in blood leukocyte DNA was lower in GC cases than healthy controls [28]. To our best knowledge, this is the first study to explore the relationship of COX-2 methylation in blood leukocyte DNA and risk of GC.

Human COX-2 gene is located in 1q25.2–25.3, consisting of 10 exons and 9 introns. In the 5′-flanking region, there is a CpG island containing several potential transcription factor binding sites, including two NF-κB sites, two AP-2 sites, three SP1 sites, one C/EBP motif, one Ets-1 site, and one CRE site [29]. SP1 and AP-2 were two human transcription factors, which play critical roles in regulating gene expression during embryonic early development [30–35]. We selected a 75 bp region containing 7 CpG sites in the downstream of the transcriptional starting codon from −296 to −222 with one SP1 binding site and one AP-2 binding site.

In this study, we found that COX-2 methylation existed in blood leukocyte DNA, but at a low level. The median of COX-2 methylation levels was only 2.2 % in SG/mild CAG group. A previous study reported that the frequency of COX-2 hypermethylation was 88 % in primary prostate cancer tissues [36]. However, a German study showed that the frequency of COX-2 hypermethylation was only 2.4 % in serum of prostate cancer [37]. Another study using microdissected foci collected from esophageal cancer patients showed that COX-2 methylation was more common in subepithelial lymphocytes than in epithelial foci or non-lymphocytic stromal tissues [38]. These findings suggested that COX-2 methylation might have tissue specificity.

In the present study, we did not found association between COX-2 methylation in blood leukocyte DNA and risk of GC. However, the temporal trend analysis showed that COX-2 methylation levels were elevated at 1–4 years ahead of clinical GC diagnosis. Further validation using 31 GC cases with both pre- and post-GC blood samples indicated that COX-2 methylation levels were significantly increased before GC diagnosis, suggesting that subjects with higher COX-2 methylation levels in blood leukocyte DNA may increase the GC risk. However, no significant association between COX-2 methylation and risk of progression to GC was found in subjects with IM and DYS who progressed to GC in contrast to those remained with IM and DYS. It may speculate that COX-2 methylation levels mainly increased 1–4 years but not 5–10 years prior to clinical diagnosis. For subjects with IM or DYS who progressed to GC, the blood samples were collected not only at 1–4 years (18 IM, 20 DYS), but also at 5–10 years (15 IM, 15 DYS). Due to the small sample size, we cannot conduct a stratified analysis. Further study with a large sample size is warranted to confirm our results. In addition, because COX-2 methylation levels in blood leukocyte DNA were very low, more studies are needed to identify potential biomarkers for GC diagnosis.

The mechanism for blood leukocyte DNA methylation of COX-2 and risk of GC is still unclear. Until now, no study focused on the mechanism of blood leukocyte DNA methylation and carcinogenesis process, and whether DNA methylation levels in blood leukocytes could represent those in tissues was still unclear. Studies showed that COX-2 mRNA and protein expression were frequently up-regulated in human GC tissue and cell lines [39–41], and 5-aza-deoxycytidine treatment could increase both COX-2 mRNA and protein expression in vitro [42–44]. Another study found that treatment of COX-2-methylated cells with 5-azacytidine had a modest effect on COX-2 expression, but when 5-azacytidine-treated cells were subsequently stimulated with H. pylori, there was a significant, 5–10-fold enhancement of both COX-2 mRNA and protein expression [9]. These findings suggested that COX-2 methylation may be involved in gastric carcinogenesis via regulation COX-2 mRNA and protein expression. However, the biological significance of blood leukocyte DNA methylation of COX-2 needs further studies.

Growing evidences demonstrated that age, environment and lifestyle factors may modify DNA methylation [45–47]. Studies on specific gene methylation showed that CDH1, p53, RUNX3, p16 methylation levels were significant higher in older persons [27, 48]. Aging is associated with global hypomethylation of DNA and hypermethylation of specific genes [49–51]. In our study, we found higher COX-2 methylation levels in blood leukocytes in older persons, consistent with the hypothesis and previous studies. H. pylori infection was a well-known factor which was associated with methylation of many tumor-related genes [5, 52]. A study suggested that loss of COX-2 methylation might facilitate COX-2 expression, which associates with H. pylori infection [9]. In the current study, we found that COX-2 methylation levels were lower in subjects who ever infected with H. pylori. We were also interested in association between differentiation types, metastasis and surgery status of GC and COX-2 methylation levels. Based on our available data, we found that subjects with poor differentiation, metastasis and without surgery had low methylation levels compared with those with moderate/high differentiation, without metastasis and surgery. However, no significant differences were found (data not shown).

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, all subjects came from a high-risk area of GC, containing various pathological diagnosed samples. Secondly, our study had pre-GC diagnosis blood samples for the dynamic observation of COX-2 methylation and also for the comparison of methylation levels between subjects progressed and non-progressed to GC. Instead of normal controls, we selected SG/mild CAG subjects as references, however, this “sub-normal” control could only lead to the dilution of disparity between comparison groups. In addition, because of the limited number of GC cases (n = 31) with both pre- and post-GC samples, unmatched samples were also analyzed for COX-2 methylation alteration before and after GC diagnosis. While, no significant difference was found probably due to the confounders difficult to control.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our population-based nested case–control study found COX-2 methylation in blood leukocyte DNA was at a low level, but may change during GC development. Further studies on methylation of specific genes in blood leukocyte DNA are needed for efficient biomarkers of GC early detection.

Abbreviations

- COX-2:

-

Cyclooxygenase 2

- CAG:

-

Chronic atrophic gastritis

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DYS:

-

Dysplasia

- GC:

-

Gastric cancer

- H. pylori :

-

Helicobacter pylori

- IM:

-

Intestinal metaplasia

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- QMSP:

-

Quantitative methylation-specific PCR

- SG:

-

Superficial gastritis

References

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90.

Ushijima T, Nakajima T, Maekita T. DNA methylation as a marker for the past and future. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:401–7.

Ushijima T, Sasako M. Focus on gastric cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:121–5.

Nanus DM, Kelsen DP, Mentle IR, Altorki N, Albino AP. Infrequent point mutations of ras oncogenes in gastric cancers. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:955–60.

Chan AOO, Lam SK, Wong BCY, Wong WM, Yuen MF, Yeung YH, et al. Promoter methylation of E-cadherin gene in gastric mucosa associated with Helicobacter pylori infection and in gastric cancer. Gut. 2003;52:502–6.

Zou XP, Zhang B, Zhang XQ, Chen M, Cao J, Liu WJ. Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in early gastric adenocarcinoma and precancerous lesions. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1534–42.

Li WQ, Pan KF, Zhang Y, Dong CX, Zhang L, Ma JL, et al. RUNX3 methylation and expression associated with advanced precancerous gastric lesions in a Chinese population. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:406–10.

de Maat MF, van de Velde CJ, Umetani N, de Heer P, Putter H, van Hoesel AQ, et al. Epigenetic silencing of cyclooxygenase-2 affects clinical outcome in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4887–94.

Akhtar M, Cheng YL, Magno RM, Ashktorab H, Smoot DT, Meltzer SJ, et al. Promoter methylation regulates Helicobacter pylori-stimulated cyclooxygenase-2 expression in gastric epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2399–403.

Tsujii M, Dubois RN. Alterations in cellular adhesion and apoptosis in epithelial-cells overexpressing prostaglandin-endoperoxide-synthase-2. Cell. 1995;83:493–501.

Singh B, Berry JA, Shoher A, Ramakrishnan V, Lucci A. COX-2 overexpression increases motility and invasion of breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:1393–9.

Patti R, Gumired K, Reddanna P, Sutton LN, Phillips PC, Reddy CD. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in human primitive neuroectodermal tumors: effect of celecoxib and rofecoxib. Cancer Lett. 2002;180:13–21.

Secchiero P, Barbarotto E, Gonelli A, Tiribelli M, Zerbinati C, Celeghini C, et al. Potential pathogenetic implications of cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in B chronic lymphoid leukemia cells. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1599–607.

Liu F, Pan K, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ma J, et al. Genetic variants in cyclooxygenase-2: Expression and risk of gastric cancer and its precursors in a Chinese population. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1975–84.

Toyota M, Shen L, Ohe-Toyota M, Hamilton SR, Sinicrope FA, Issa JPJ. Aberrant methylation of the Cyclooxygenase 2 CpG island in colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4044–8.

Wang BC, Guo CQ, Sun C, Sun QL, Liu GY, Li DG. Mechanism and clinical significance of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3240–4.

Hur K, Song SH, Lee HS, Kim WH, Bang YJ, Yang HK. Aberrant methylation of the specific CpG island portion regulates cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in human gastric carcinomas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:844–51.

You WC, Zhang L, Gail MH, Chang YS, Liu WD, Ma JL, et al. Gastric cancer: Helicobacter pylori, serum vitamin C, and other risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1607–12.

You WC, Brown LM, Zhang L, Li JY, Jin ML, Chang YS, et al. Randomized double-blind factorial trial of three treatments to reduce the prevalence of precancerous gastric lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:974–83.

Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–81.

Rugge M, Correa P, Dixon MF, Hattori T, Leandro G, Lewin K, et al. Gastric dysplasia - The Padova international classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:167–76.

Sun Y, Deng DJ, You WC, Bai H, Zhang L, Zhou J, et al. Methylation of p16 CpG islands associated with malignant transformation of gastric dysplasia in a population-based study. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5087–93.

Eads CA, Lord RV, Wickramasinghe K, Long TI, Kurumboor SK, Bernstein L, et al. Epigenetic patterns in the progression of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3410–8.

Zhang L, Blot WJ, You WC, Chang YS, Kneller RW, Jin ML, et al. Helicobacter pylori antibodies in relation to precancerous gastric lesions in a high-risk Chinese population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1996;5:627–30.

Rusiecki JA, Al-Nabhani M, Tarantini L, Chen L, Baccarelli A, Al-Moundhri MS. Global DNA methylation and tumor suppressor gene promoter methylation and gastric cancer risk in an Omani Arab population. Epigenomics. 2011;3:417–29.

Gao Y, Baccarelli A, Shu XO, Ji BT, Yu K, Tarantini L, et al. Blood leukocyte Alu and LINE-1 methylation and gastric cancer risk in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:585–91.

Al-Moundhri MS, Al-Nabhani M, Tarantini L, Baccarelli A, Rusiecki JA. The Prognostic Significance of Whole Blood Global and Specific DNA Methylation Levels in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Plos One. 2010;5(12):e15585.

Yuasa Y, Nagasaki H, Oze I, Akiyama Y, Yoshida S, Shitara K, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 2 hypomethylation of blood leukocyte DNA is associated with gastric cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2596–603.

Appleby SB, Ristimaki A, Neilson K, Narko K, Hla T. Structure of the human cyclo-oxygenase-2 gene. Biochem J. 1994;302:723–7.

Samson SLA, Wong NCW. Role of Sp1 in insulin regulation of gene expression. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;29:265–79.

Marin M, Karis A, Visser P, Grosveld F, Philipsen S. Transcription factor Sp1 is essential for early embryonic development but dispensable for cell growth and differentiation. Cell. 1997;89:619–28.

Worrad DM, Ram PT, Schultz RM. Regulation of gene expression in the mouse oocyte and early preimplantation embryo: developmental changes in Sp1 and TATA box-binding protein, TBP. Development. 1994;120:2347–57.

Williams T, Tjian R. Characterization of a dimerization motif in ap-2 and its function in heterologous dna-binding proteins. Science. 1991;251:1067–71.

Williams T, Tjian R. Analysis of the dna-binding and activation properties of the human transcription factor ap-2. Genes Dev. 1991;5:670–82.

Hilger-Eversheim K, Moser M, Schorle H, Buettner R. Regulatory roles of AP-2 transcription factors in vertebrate development, apoptosis and cell-cycle control. Gene. 2000;260:1–12.

Yegnasubramanian S, Kowalski J, Gonzalgo ML, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Walsh PC, et al. Hypermethylation of CpG islands in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1975–86.

Ellinger J, Haan K, Heukamp LC, Kahl P, Buettner R, Mueller SC, et al. CpG island hypermethylation in cell-free serum DNA identifies patients with localized prostate cancer. Prostate. 2008;68:42–9.

Dawsey SP, Roth MJ, Adams L, Hu N, Wang QH, Taylor PR, et al. COX-2 (PTGS2) gene methylation in epithelial, subepithelial lymphocyte and stromal tissue compartments in a spectrum of esophageal squamous neoplasia. Cancer Detect Prev. 2008;32:135–9.

Uefuji K, Ichikura T, Mochizuki H. Increased expression of interleukin-1alpha and cyclooxygenase-2 in human gastric cancer: a possible role in tumor progression. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3225–30.

Yasuda H, Yamada M, Endo Y, Inoue K, Yoshiba M. Elevated cyclooxygenase-2 expression in patients with early gastric cancer in the gastric pylorus. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:690–7.

Ristimaki A, Honkanen N, Jankala H, Sipponen P, Harkonen M. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1276–80.

Meng XY, Zhu ST, Zong Y, Wang YJ, Li P, Zhang ST. Promoter hypermethylation of cyclooxygenase-2 gene in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:444–9.

Fernandez-Alvarez A, Llorente-Izquierdo C, Mayoral R, Agra N, Bosca L, Casado M, et al. Evaluation of epigenetic modulation of cyclooxygenase-2 as a prognostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogenesis. 2012;1:e23.

Ma X, Yang Q, Wilson KT, Kundu N, Meltzer SJ, Fulton AM. Promoter methylation regulates cyclooxygenase expression in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R316–21.

Lim U, Song MA. Dietary and lifestyle factors of DNA methylation. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;863:359–76.

Herceg Z. Epigenetics and cancer: towards an evaluation of the impact of environmental and dietary factors. Mutagenesis. 2007;22:91–103.

Mathers JC, Strathdee G, Relton CL. Induction of epigenetic alterations by dietary and other environmental factors. Adv Genet. 2010;71:3–39.

Suga Y, Miyajima K, Oikawa T, Maeda J, Usuda J, Kajiwara N, et al. Quantitative p16 and ESR1 methylation in the peripheral blood of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:1137–42.

Richardson B. Impact of aging on DNA methylation. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2:245–61.

Gryzinska M, Blaszczak E, Strachecka A, Jezewska-Witkowska G. Analysis of Age-Related Global DNA Methylation in Chicken. Biochem Genet. 2013;51(7-8):554–63.

Keyes MK, Jang H, Mason JB, Liu Z, Crott JW, Smith DE, et al. Older age and dietary folate are determinants of genomic and p16-specific DNA methylation in mouse colon. J Nutr. 2007;137:1713–7.

Maekita T, Nakazawa K, Mihara M, Nakajima T, Yanaoka K, Iguchi M, et al. High levels of aberrant DNA methylation in Helicobacter pylori - Infected gastric mucosae and its possible association with gastric cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:989–95.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by A3 Foresight Program from Natural Science Foundation of China (30921140311), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81171989 and 30801346), and National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program: 2010CB529303).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WCY and KFP conceived and designed the study, reviewed and modified the paper; HJS and YZ performed the experimental work, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; LZ and JLM contributed to the collection of samples and information data; JYL in charge of the histopathologic diagnosis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Hui-juan Su and Yang Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, Hj., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L. et al. Methylation status of COX-2 in blood leukocyte DNA and risk of gastric cancer in a high-risk Chinese population. BMC Cancer 15, 979 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1962-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1962-x