Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this pilot study was to examine relationships between body image, perceived stress, partner and patient-provider sexual communication, and sexual functioning in women with advanced stages of cervical cancer (CC) after the cancer diagnosis.

Methods

In this pilot study, cancer patients (n = 30) and healthy women (n = 30) were compared. A study was conducted from January to March 2022. Sexual functioning and its predictors were assessed using the 6-item Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI-6), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), the Sexual Communication Self-Efficacy Scale (SCSES), the self-administered questionnaire contributing the patient-provider sexual communication, and the Body Esteem Scale (BES). The data was collected from January to June 2022.

Results

Women with cervical cancer after the diagnosis reported impaired sexual functioning, which was associated with self-efficacy in sexual communication, feeling comfortable discussing sexual issues with a healthcare provider, perceived stress, and body image. Compared to the control group, CC patients had significantly lower sexual functioning (mean 8.83 vs 19.23; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Sexual functioning in women with CC is significantly impaired even after the diagnosis and is associated with psychosocial variables. The expanded study will include other predictors of sexual functioning and quality of life in women with CC on the larger group of patients.

Policy Implications

As cancer becomes a more chronic disease that affects even younger individuals, social policy should promote the sexuality issues in cancer patients, as it is an integral part of every person’s life, regardless of health status or age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The incidence of cervical cancer (CC) in Poland is moderate compared to other countries in the world. CC is the third most common cancer in women worldwide. More than 85% of new cases occur in developing countries, with over 54,000 reported in Europe since 2009. The highest number of cases in Poland occurs in the group of women between 40 and 64 years old (62.4% of all patients). Recent years indicate an increase in the number of cases in younger women (from 35 to 44 years old) (Wojciechowska & Didkowska, 2022). The diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer can impair quality of life (QoL), as well as sexual and emotional functioning, and women’s body image (Bacalhau et al., 2020; Bisson et al., 2002; Greimel et al., 2009; Hughes, 2000).

The above-mentioned functioning can be distinct in every stage of the disease, with the first symptoms after receiving the diagnosis. The cancer diagnosis can be associated with increased distress, anxiety, and depression. Tavoli et al. (2007) proved that receiving the diagnosis significantly elevates distress and anxiety levels (M = 6.3 before the diagnosis, M = 9.1 after the diagnosis). It is mainly related to fear of death, treatment consequences, and the time of the treatment anticipation. Available works show that changes in areas of emotional and social functioning and, in some cases, experiencing physical symptoms can deteriorate the QoL among patients even before the beginning of the treatment (Bacon et al., 2001; Montazeri et al., 2009).

An important aspect of quality of life is sexual functioning, which can be significantly interfered or even excluded by the diagnosis and treatment of the disease, not only due to physiological changes caused by the disease or treatment but also due to psychological difficulties (Frumovitz et al., 2005; Hordern & Street, 2007; Nelson et al., 2011). The previously conducted systematic review of sexual functioning in CC patients showed that women experience pain during sexual intercourse, vaginal dryness, and decreased levels of satisfaction and sexual interest (Liberacka-Dwojak & Izdebski, 2021). Some authors described that sexual dysfunctions are very common after the diagnosis (Galbraith & Crighton, 2008; Massie, 2004; Moore et al., 2003) since a cancer diagnosis can trigger a range of emotions that include frustration, anxiety, anger, irritability, or loneliness, which can potentially affect sexuality, especially during the desire phase (Ganz et al., 2019). Sexuality is also inextricably linked to body image and a sense of femininity/masculinity. Women with cervical cancer often suffered from bodily distress and claimed that they feel less feminine due to their illness and treatment. It could lead to a decrease in sexual satisfaction and intimacy, as self-esteem and body image is a relevant predictors of worsened sexual functioning, which is one of the greatest restrictions in terms of quality of life (Bacalhau et al., 2020; Hassan et al., 2021; Hawighorst-Knapstein et al., 2004; Thapa et al., 2018).

Sexuality among women is positively associated with sexual communication among partners (Badr & Carmack Taylor, 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009). However, the treatment of CC is a specific situation that should include the involvement of the patient, doctors, and partners. Therefore, it is relevant to anticipate both partner and patient-provider sexual communication. Only 7–40% of CC survivors claimed that they sought or received help with sexual difficulties from healthcare providers (Vermeer et al., 2015), while almost 90% of cancer patients reported that their oncologists rarely discussed sexual issues (Flynn et al., 2012). The literature suggests that patients also often avoid discussing sexuality issues with their partners in terms of cancer, regarding discomfort, awkwardness in self-disclosing, low self-efficacy in sexual communication, and low self-esteem leading to lower sexual satisfaction, anxiety, or feelings of inadequacy (Cleary & Hegarty, 2011; Hawkins et al., 2009).

In conclusion, the cancer diagnosis is often perceived as a traumatic situation and therefore triggers many severe emotional reactions, mainly anxiety, which can be experienced by approximately 10–30% of cancer patients (Levin & Alici, 2010). The experience of distress is equally common, however prolonged and poorly tolerated distress could hinder functioning and lead to depression. It is estimated that depressive symptoms appear in about 10–25% of patients (Fann et al., 2008; Miller & Massie, 2010). It indicates the relevance of psychological interactions with patients before the treatment, due to the increased intensity of anxiety and depression after receiving the diagnosis (Cardoso et al., 2016).

The purpose of this study was to examine relationships between body image, perceived stress, partner and patient-provider sexual communication, and sexual functioning after the diagnosis to better understand sexuality issues in women with CC so that suitable interventions could be identified for clinical management. The primary aim was to examine those relationships, while the secondary aim was to compare cervical cancer patients with the control group. To better understand sexuality issues in women with CC, a pilot study was conducted on women referred to the Franciszek Łukaszczyk Oncology Centre in Bydgoszcz.

Methods

A pilot study was conducted at the Department of Radiotherapy and the Department of Clinical Brachytherapy at the Franiszek Łukaszczyk Oncology Centre in Bydgoszcz, Poland. The Bioethics Committee agreement was obtained (no. KB 464/2020) from the Bioethics Committee of the Nicolaus Copernicus University functioning at Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz on 27.10.2020. The informed consent was obtained from the participants. The data was collected from January to June 2022.

Participants

This study employs a cross-sectional study design. To gain a homogenous group of patients with similar treatment methods, only women with advanced stages of CC were recruited. In that case, 30 CC patients in stages IIb to IIIa at the beginning of radiotherapy or brachytherapy treatment were enrolled. The 30 healthy women were recruited for the control group. We expect to recruit 60 subjects in each group in the final study.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients aged 40–65 as a range of middle adulthood; (2) patients diagnosed with CC with IIb to IIIa stage by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO); (3) patients classified for the radiotherapy or brachytherapy treatment; and (4) patients who did not experience any other untreated medical issues which could affect their sexuality such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or depression. The subjects for the control group were enrolled with the inclusion criteria as follows: (1) subjects aged 40–65; and (2) subjects who were not diagnosed with any cancer or any untreated medical issues which could affect their sexuality. All subjects in both groups had to be sexually active and had to agree to participate in the study and sign an informed consent form.

Study Methods

Data were acquired by using questionnaires, which have high reliability and validity. All necessary agreements were obtained from the questionnaire authors.

Sexual functioning was measured using the 6-item Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI-6), a 6-item multiple-choice questionnaire. The survey measures five domains, including sexual desire arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain (Isidori et al., 2010). An FSFI-6 score of 19 or below was considered abnormal (Pontallier et al., 2016). The reliability was 0.87. As the FSFI-6 was not used in the Polish population, the model fit was checked. The results showed good fit (chi2 = 6.391; CFI = 0.999; TLI = 0.997; RFI = 0.947; RMSEA = 0.027).

Perceived stress was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), which is a 10-item questionnaire evaluating the degree to which an individual has perceived life as unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloading (Cohen et al., 1983). The reliability was 0.92.

Two instruments were used to examine sexual communication. The Sexual Communication Self-Efficacy Scale (SCSES) measures respondents’ confidence in engaging in a variety of activities with a sexual partner. The 22 items provide five factors which are contraception communication, positive sexual messages, negative sexual messages, and condom negotiation (Quinn-Nilas et al., 2016). The reliability was 0.98. A self-administered questionnaire contributing the patient-provider sexual communication was used. The five items that referred to the presence of discussion about sexual activity before and after the cancer diagnosis (from the provider and patient side) were scored as yes–no answers and the level of comfortability during such discussions was scored on the 5-point Likert scale. The version for the control group included three items. The reliability was 0.69 for the CC group and 0.72 for the control group.

Finally, the Body Esteem Scale was used to assess body image. The 35-item scale refers to the three domains such as sexual attractiveness, weight concern, and physical condition (Franzoi & Shields, 1984). The reliability was 0.97.

Demographic data, including age, level of education, place of residence, number of children, marital status, and medical issues, including HPV vaccination, regular gynecological screening tests, menopausal status, and other medical comorbidities, were collected for all participants. The CC patients were also asked about the stage of cancer, treatment type, previous colposcopy, and the date of their cancer diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed with SPSS version 26 statistical software packages. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the subject. The factors related to the sexual functioning and differences between groups were analyzed with Pearson correlation and bivariate analyses, which were Student’s t-test and ANOVA depending on the number of categories of independent variables. A two-sided significance level of 5% was used in all analyses. All variables were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test).

Results

Demographic and clinical data, including age, education, marital status, menopausal status, comorbidities, HPV vaccination, and regular screening tests in CC patients and control group, are shown in Table 1. The mean age in CC group was 56.20 (SD = 6.13) and 53.60 (SD = 4.34) in control group. In total, 66.67% of women with cervical cancer and 63.33% of the control group claimed to have comorbidities; these were mostly diabetes, hypertension, and hypothyroidism. All women reported being under treatment for these comorbidities to exclude the potential impact of illnesses on sexual functioning (Table 1).

Overall, 43.33% (n = 13) of cervical cancer patients were stage IIb and 56.67% (n = 17) were stage IIIa as classified by FIGO. The median interval from the start of the treatment to the current study was 1.02 weeks (SD = 1.12) which shows that the study involves women at the beginning of their treatment.

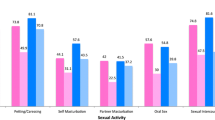

The patients received radiotherapy or brachytherapy. All women stated that sexual activity was understood to be any sexual contact with partners, including kissing or petting. However, the score of sexual functioning in the CC group was reported as low (see Table 2). The scores of the questionnaires in the CC group and control group and the variables associated with sexual functioning in women with cervical cancer are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Among the scales, FSFI-6 scores were significantly different between the groups (t(58) = − 12.19; p < 0.001).

Sexual functioning in the CC group was positively associated with all domains of sexual communication self-efficacy (p < 0.001), all domains of body esteem (p < 0.05), and the perceived level of stress (p = 0.001). Women who initiated discussions about sexual issues with providers during their screening visits and those who felt more comfortable during such discussions presented a higher level of sexual functioning (Table 4).

Discussion

The study aimed to gain information about sexuality, body image, and communication in women with cervical cancer after the cancer diagnosis. Many studies refer to sexuality and quality of life in long-term CC survivors, although there has been a limited number of studies concerning women with CC at the beginning of their treatment (Grion et al., 2016). The median interval from the beginning of the treatment to the current study was 1.02 weeks, which is highly relevant for understanding the results. Moreover, in the present pilot study, the questionnaires referred to the perception of sexual functioning in the last 4 weeks, so it refers to the time of treatment anticipation. Diagnosis of cancer could be a life-threatening event that prompts psychological distress, anxiety, fear of death, and deterioration in the quality of life (Mcbride et al., 2000; Schofield et al., 2003). As shown in the literature, women at the beginning of treatment have to cope with changes in social interactions, physical changes, reconstructing self-identity, and body image (Ching et al., 2009). Women in our study were diagnosed with advanced stages of CC (IIb and IIIa by FIGO) which could also be associated with distress as a more life-threatening experience (Distefano et al., 2008). It implicates the need to investigate other aspects and predictors of quality of life in women at the start of their illness.

Women with gynecological cancer may experience decreased sexual function from the moment of diagnosis (Grion et al., 2016), which could result from psychological symptoms after diagnosis or treatment-related issues. Women reported a significant impairment of sexual functioning in comparison to the control group, with results implicating no sexual dysfunctions, which is consistent with previous studies regarding sexuality in CC patients (Cleary & Hegarty, 2011; Ekwall et al., 2003; Grion et al., 2016; Roussin et al., 2021; Thapa et al., 2018). The perception of sexual activity in women is considered to be very interesting in terms of understanding the results. The FSFI-6 questionnaire consists of six questions regarding the overall level of arousal, the arousal during sexual activity, lubrication, orgasm, sexual satisfaction, and pain during penetration (Isidori et al., 2010). Although they reported so many vagina-related issues that penetration was not possible, women still consider sexual activity to be any other activity concerning intimacy with their partner (kissing, petting, etc.). Many of them reported their sexual satisfaction to be high as they were close to their partners. It manifests the need to enhance the understanding of sexual activity as intimacy and closeness between partners, especially in terms of illness that disrupts sexual functions.

Furthermore, researches implicate the relevant role of sexual communication in better sexual functioning (Flynn et al., 2012; Hordern & Street, 2007; Vermeer et al., 2015), similar to conducted research (correlation between sexual functioning and self-efficacy in sexual communication: r = 0.654–0.736; p < 0.001). Open sexual communication is associated with a better quality of life, lower level of distress, and increased satisfaction and closeness between partners (Hawkins et al., 2009). Such results could be a promising solution for psychosexual issues of CC patients to implicate interventions to help couples adapting changes in sexuality which should not focus exclusively on sexual functions but rather on intimacy between partners (Walker et al., 2017). The literature review outlines the risk factors for sexual dysfunctions mostly as a higher level of depression, distress, and lowers social support (Frumovitz et al., 2005; Hankey et al., 1999; Kamen et al., 2015). As sexuality is a consistent part of the quality of life (Douglas & Fenton, 2013), it confirms the results obtained to consider psychosexual interventions for women during CC treatment as promising to increase their functioning in many areas. Moreover, feeling comfortable in discussions about sexual issues with healthcare providers differentiates the sexual functioning in CC patients (F(1(28) = 8.09; p < 0.05). Patients may find it burdensome to start a conversation about sexual issues. Healthcare providers should be aware that women with cervical cancer are vulnerable to sexual dysfunction and should therefore initiate such discussions with patients to lower their level of stress (Sporn et al., 2015).

Analysis of the factors associated with worsened sexual functioning revealed a significant association between body image and perceived stress. The literature implies that women with gynecological cancers report concerns about body image and sexuality due to a loss of physical integrity (Sacerdoti et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2016). Such side effects of treatment anticipation, like hair loss, infertility, premature menopause, weight gain, scarring, or disfigurement of the genital organs, can impact the perception of their own body (Sacerdoti et al., 2010). Most studies reveal that diagnosis, treatment, and side effects may be associated with higher distress. There is a significant relationship between perceived stress and sexual function (Abedi et al., 2015). In the other study, Bagherzadeh et al. (2021) reported the positive effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction training on revealing sexual dysfunction in women with breast cancer. It suggests that distress could be associated with sexual functioning and thus the psychological interventions aimed at stress could positively impact other aspects of functioning in other groups of cancer patients.

Clinical and Social Policy Implications

Based on the results of the pilot study, there are some implications for psychosocial and clinical interventions. Previous research focused mostly on the treatment effects or late effects of cancer. The conducted pilot study revealed that the time after diagnosis should not be ignored, as the cancer diagnosis can trigger various emotions and symptoms, like anxiety, depression, fear, impaired quality of life, and sexuality. An education program or psychological interventions for women after CC diagnosis could improve their emotional functioning and thus contribute to a better quality of life and sexual functioning. It could be helpful to improve women’s self-efficacy in sexual communication, both with their partners and with healthcare providers. It would also be profitable for patients to intensify doctors’ sensitivity to sexual-related issues since the results show that sexuality changes even after the cancer diagnosis. Patient-provider sexual communication at this time could be a protective factor against further sexual dysfunctions and assist patients to cope with such changes.

The pilot study raises an additional problem that has implications for social policy. Concerns regarding sexual needs in cancer may seem controversial or unconventional in a society where so-called positive-sexuality attitudes are taboo topics. To improve awareness of sexual issues among cancer patients, as well as to support sexuality concerns generally in chronic and acute diseases, educational efforts are required both outside and inside patients. To boost one’s self-efficacy in sexual communication, such support should address sexuality issues that affect both men and women across all age groups. It could apply education about sharing positive and negative feedback, contraception issues, or sexual health, both with partners, children, or medical providers. Meeting a patient’s needs is crucial for maintaining healthy sexuality and raising awareness of the importance of sexual issues, as it is an integral part of every person’s life. Moreover, such efforts could contribute to facilitating the medical providers to conduct an open discussion about sexual health issues with their patients, regardless of health status or age. As cancer becomes a more chronic disease that affects even younger individuals, social policy should promote the sexuality issues in cancer patients.

Study Limitations

The limitations of this pilot study included the small sample. However, the purpose of conducting a pilot study is to improve the design for an expanded study. The cross-sectional design of the study does not allow the scores before and after treatment to be compared, which could change over time. Future studies could be improved by conducting longitudinal and intervention studies to evaluate the sexual functioning and its predictors of CC patients.

Conclusions

Women with cervical cancer after the cancer diagnosis reported impaired sexual functioning, which was associated with self-efficacy in sexual communication, feeling comfortable in discussing sexual issues with a healthcare provider, perceived stress, and body image. It is relevant to implicate the psychosexual interventions from the beginning of the treatment or even before, to help women adapt to changes in sexuality and quality of life. The healthcare provider should be aware that women with cancer are vulnerable to sexual dysfunctions. Furthermore, as cancer becomes a more chronic disease that affects even younger individuals, social policy should promote the sexuality issues in cancer patients, as it is an integral part of every person’s life, regardless of health status or age. The expanded study will be conducted and will respect other predictors of sexual functioning and quality of life in women with cervical cancer in the larger group of patients.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abedi, P., Afrazeh, M., Javadifar, N., & Saki, A. (2015). The relation between stress and sexual function and satisfaction in reproductive-Age women in iran: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 41(4), 384–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2014.915906

Bacalhau, M., do, R. R. N., Pedras, S., & da Graça Pereira Alves, M. (2020). Attachment style and body image as mediators between marital adjustment and sexual satisfaction in women with cervical cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(12), 5813–5819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05423-y

Bacon, C. G., Giovannucci, E., Testa, M., & Kawachi, I. (2001). The impact of cancer treatment on quality of life outcomes for patients with localized prostate cancer. Journal of Urology, 166(5), 1804–1810. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(05)65679-0

Badr, H., & Carmack Taylor, C. L. (2009). Sexual dysfunction and spousal communication in couples coping with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 18(7), 735–746. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1449

Bagherzadeh, R., Sohrabineghad, R., Gharibi, T., Mehboodi, F., & Vahedparast, H. (2021). Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction training on revealing sexual function in Iranian women with breast cancer. Sexuality and Disability, 39(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09660-1

Bisson, J. I., Chubb, H. L., Bennett, S., Mason, M., Jones, D., & Kynaston, H. (2002). The prevalence and predictors of psychological distress in patients with early localized prostate cancer. BJU International, 90(1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.02806.x

Cardoso, G., Graca, J., Klut, C., Trancas, B., & Papoila, A. (2016). Depression and anxiety symptoms following cancer diagnosis: A cross-sectional study. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 21(5), 562–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2015.1125006

Ching, S. S. Y., Martinson, I. M., & Wong, T. K. S. (2009). Reframing: Psychological adjustment of Chinese women at the beginning of the breast cancer experience. Qualitative Health Research, 19(3), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309331867

Cleary, V., & Hegarty, J. (2011). Understanding sexuality in women with gynaecological cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 15(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2010.05.008

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

Distefano, M., Riccardi, S., Capelli, G., Costantini, B., Petrillo, M., Ricci, C., Scambia, G., & Ferrandina, G. (2008). Quality of life and psychological distress in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered pre-operative chemoradiotherapy. Gynecologic Oncology, 111(1), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.034

Douglas, J. M., & Fenton, K. A. (2013). Understanding sexual health and its role in more effective prevention programs. Public Health Reports, 128(SUPPL. 1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549131282s101

Ekwall, E., Ternestedt, B. M., & Sorbe, B. (2003). Important aspects of health care for women with gynecologic cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 30(2), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1188/03.ONF.313-319

Fann, J. R., Thomas-Rich, A. M., Katon, W. J., Cowley, D., Pepping, M., McGregor, B. A., & Gralow, J. (2008). Major depression after breast cancer: A review of epidemiology and treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry, 30(2), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.10.008

Flynn, K. E., Reese, J. B., Jeffery, D. D., Abernethy, A. P., Lin, L., Shelby, R. A., Porter, L. S., Dombeck, C. B., & Weinfurt, K. P. (2012). Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 21(6), 594–601. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1947

Franzoi, S. L., & Shields, S. A. (1984). The Body Esteem Scale: Multidimensional structure and sex differences in a college population. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(2), 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4802_12

Frumovitz, M., Sun, C. C., Schover, L. R., Munsell, M. F., Jhingran, A., Wharton, J. T., Eifel, P., Bevers, T. B., Levenback, C. F., Gershenson, D. M., & Bodurka, D. C. (2005). Quality of life and sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(30), 7428–7436. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3996

Galbraith, M. E., & Crighton, F. (2008). Alterations of sexual function in men with cancer. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 24(2), 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2008.02.010

Ganz, B. P. A., Desmond, K. A., Belin, T. R., Meyerowitz, B. E., & Rowland, J. H. (2019). Predictors of sexual health in women after breast cancer diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 17(8), 2371–2380.

Greimel, E. R., Winter, R., Kapp, K. S., & Haas, J. (2009). Quality of life and sexual functioning after cervical cancer treatment: A long-term follow-up study. Psycho-Oncology, 18(5), 476–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1426

Grion, R. C., Baccaro, L. F., Vaz, A. F., Costa-Paiva, L., Conde, D. M., & Pinto-Neto, A. M. (2016). Sexual function and quality of life in women with cervical cancer before radiotherapy: A pilot study. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 293(4), 879–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3874-z

Hankey, B. F., Feuer, E. J., Clegg, L. X., Hayes, R. B., Julie, M., Prorok, P. C., Ries, L., & a, Merrill, R. M., & Kaplan, R. S. (1999). Cancer surveillance series: Interpreting trends in. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 91(12), 1017–1024.

Hassan, H. E., Masaud, H., Mohammed, R., & Ramadan, S. (2021). Self-knowledge and body image among cervical cancer survivors women in Northern Upper Egypt. Futher Applied Healthcare, 1(1), 1–12.

Hawighorst-Knapstein, S., Fusshoeller, C., Franz, C., Trautmann, K., Schmidt, M., Pilch, H., Schoenefuss, G., Georg Knapstein, P., Koelbl, H., Kelleher, D. K., & Vaupel, P. (2004). The impact of treatment for genital cancer on quality of life and body image - Results of a prospective longitudinal 10-year study. Gynecologic Oncology, 94(2), 398–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.04.025

Hawkins, Y., Ussher, J., Gilbert, E., Perz, J., Sandoval, M., & Sundquist, K. (2009). Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Cancer Nursing, 32(4), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0b013e31819b5a93

Hordern, A. J., & Street, A. F. (2007). Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: Mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Medical Journal of Australia, 186(5), 224–227. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00877.x

Hughes, M. K. (2000). Sexuality and the cancer survivor: A silent coexistence. Cancer Nursing, 23(6), 477–482. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002820-200012000-00011

Isidori, A. M., Pozza, C., Esposito, K., Giugliano, D., Morano, S., Vignozzi, L., Corona, G., Lenzi, A., & Jannini, E. A. (2010). Development and validation of a 6-item version of the female sexual function index (FSFI) as a diagnostic tool for female sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(3), 1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01635.x

Kamen, C., Mustian, K. M., Heckler, C., Janelsins, M. C., Peppone, L. J., Mohile, S., McMahon, J. M., Lord, R., Flynn, P. J., Weiss, M., Spiegel, D., & Morrow, G. R. (2015). The association between partner support and psychological distress among prostate cancer survivors in a nationwide study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 9(3), 492–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0425-3

Levin, T. T., & Alici, Y. (2010). Anxiety dosorders. In R. M. J. C. Holland, W. S. Breitbart, P. B. Jacobsen, M. S. Lederberg, & M. J. Loscazo (Eds.), Psycho-Oncology (2nd ed., pp. 324–331). Oxford University Press.

Liberacka-Dwojak, M., & Izdebski, P. (2021). Sexual function and the role of sexual communication in women diagnosed with cervical cancer: A systematic review. International Journal of Sexual Health, 33(3), 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2021.1919951

Massie, M. J. (2004). Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs, 10021(32), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh014

Mcbride, C. M., Clipp, E., Peterson, B. L., Lipkus, I. M., & Demark-Wahnefried, W. (2000). Psychological impact of diagnosis and risk reduction among cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 9(5), 418–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1611(200009/10)9:5%3c418::AID-PON474%3e3.0.CO;2-E

Miller, K., & Massie, M. J. (2010). Depressive disorders. In R. M. Holland, W. S. Breitbart, P. B. Jacobsen, M. S. Lederberg, & M. J. Loscazo (Eds.), Psycho-oncology (2nd ed., pp. 311–317). Oxford University Press.

Montazeri, A., Tavoli, A., Mohagheghi, M. A., Roshan, R., & Tavoli, Z. (2009). Disclosure of cancer diagnosis and quality of life in cancer patients: Should it be the same everywhere? BMC Cancer, 9, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-9-39

Moore, T. M., Strauss, J. L., Herman, S., & Donatucci, C. F. (2003). Erectile dysfunction in early, middle, and late adulthood: Symptom patterns and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 29(5), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230390224756

Nelson, C., Gilley, J., & Roth, A. (2011). The impact of a cancer diagnosis on sexual health. In J. Mulhall, L. Incrocci, I. Goldstein, & R. Rosen (Eds.), Cancer and Sexual Health (Humana Pre, pp. 407–415). www.journal.uta45jakarta.ac.id

Pontallier, A., Denost, Q., Van Geluwe, B., Adam, J. P., Celerier, B., & Rullier, E. (2016). Potential sexual function improvement by using transanal mesorectal approach for laparoscopic low rectal cancer excision. Surgical Endoscopy, 30(11), 4924–4933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-4833-x

Quinn-Nilas, C., Milhausen, R. R., Breuer, R., Bailey, J., Pavlou, M., DiClemente, R. J., & Wingood, G. M. (2016). Validation of the Sexual Communication Self-Efficacy Scale. Health Education and Behavior, 43(2), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198115598986

Roussin, M., Lowe, J., Hamilton, A., & Martin, L. (2021). Factors of sexual quality of life in gynaecological cancers: A systematic literature review. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 304(3), 791–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-021-06056-0

Sacerdoti, R. C., Laganà, L., & Koopman, C. (2010). Altered sexuality and body image after gynecological cancer treatment: How can psychologists help? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41(6), 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021428

Schofield, P. E., Butow, P. N., Thompson, J. F., Tattersall, M. H. N., Beeney, L. J., & Dunn, S. M. (2003). Psychological responses of patients receiving a diagnosis of cancer. Annals of Oncology, 14(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdg010

Sporn, N. J., Smith, K. B., Pirl, W. F., Lennes, I. T., Hyland, K. A., & Park, E. R. (2015). Sexual health communication between cancer survivors and providers: How frequently does it occur and which providers are preferred? Psycho-Oncology, 24(9), 1167–1173. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3736

Tavoli, A., Mohagheghi, M. A., Montazeri, A., Roshan, R., Tavoli, Z., & Omidvari, S. (2007). Anxiety and depression in patients with gastrointestinal cancer: Does knowledge of cancer diagnosis matter? BMC Gastroenterology, 7, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-7-28

Thapa, N., Maharjan, M., Xiong, Y., Jiang, D., Nguyen, T. P., Petrini, M. A., & Cai, H. (2018). Impact of cervical cancer on quality of life of women in Hubei, China. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30506-6

Vermeer, W. M., Bakker, R. M., Kenter, G. G., De Kroon, C. D., Stiggelbout, A. M., & Ter Kuile, M. M. (2015). Sexual issues among cervical cancer survivors: How can we help women seek help? Psycho-Oncology, 24(4), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3663

Walker, L. M., King, N., Kwasny, Z., & Robinson, J. W. (2017). Intimacy after prostate cancer: A brief couples’ workshop is associated with improvements in relationship satisfaction. Psycho-Oncology, 26(9), 1336–1346. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4147

Wilson, C. M., McGuire, D. B., Rodgers, B. L., Elswick, R. K., Menendez, S., & Temkin, S. M. (2020). Body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning in cervical and endometrial cancer: Interrelationships and women’s experiences. Sexuality and Disability, 38(3), 389–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09641-4

Wojciechowska, U., & Didkowska, J. (2022). Zachorowania i zgony na nowotwory złośliwe w Polsce. Krajowy Rejestr Nowotworów, Narodowy Instytut Onkologii Im. Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy. Retrieved September 10, 2022, from http://onkologia.org.pl/raporty/

Zhong, T., Hu, J., Bagher, S., Vo, A., O’Neill, A. C., Butler, K., Novak, C. B., Hofer, S. O. P., & Metcalfe, K. A. (2016). A comparison of psychological response, body image, sexuality, and quality of life between immediate and delayed autologous tissue breast reconstruction: A prospective long-term outcome study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 138(4), 772–780. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002536

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The Bioethics Committee of the Medical University approved the study protocol.

Informed Consent

All participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study prior to psychological examination.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liberacka-Dwojak, M., Wiłkość-Dębczyńska, M. & Ziółkowski, S. A Pilot Study of Psychosexual Functioning and Communication in Women Treated for Advanced Stages of Cervical Cancer After the Diagnosis. Sex Res Soc Policy 20, 1258–1266 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00796-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00796-1