Abstract

Background

Given the physiological changes during pregnancy, pregnant women are likely to develop recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) and pyelonephritis, which may result in adverse obstetric outcomes, including prematurity and low birth weight preeclampsia. However, data on UTI prevalence and bacterial profile in Latin American pregnant women remain scarce, necessitating the present systematic review to address this issue.

Methods

To identify eligible observational studies published up to September 2022, keywords were systematically searched in Medline/PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, and Bireme/Lilacs electronic databases and Google Scholar. The systematic review with meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, and the quality of studies was classified according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines. The meta-analysis employed a random-effects method with double-arcsine transformation in the R software.

Results

Database and manual searches identified 253,550 citations published until September 2022. Among the identified citations, 67 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review, corresponding to a sample of 111,249 pregnant women from nine Latin American countries. Among Latin American pregnant women, the prevalence rates of asymptomatic bacteriuria, lower UTI, and pyelonephritis were estimated at 18.45% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 15.45–21.53), 7.54% (95% CI: 4.76–10.87), and 2.34% (95% CI: 0.68–4.85), respectively. Some regional differences were also detected. Among the included studies, Escherichia coli (70%) was identified as the most frequently isolated bacterial species, followed by Klebsiella sp. (6.8%).

Conclusion

Pregnant women in Latin America exhibit a higher prevalence of bacteriuria, UTI, and pyelonephritis than pregnant women globally. This scenario reinforces the importance of universal screening with urine culture during early prenatal care to ensure improved outcomes. Future investigations should assess the microbial susceptibility profiles of uropathogens isolated from pregnant women in Latin America.

Trial registration

This research was registered at PROSPERO (No. CRD42020212601).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bacteriuria reportedly affects 1.78–48.3% of pregnant women [1, 2]. Its prevalence depends on the geographic region or age group analyzed. Although the frequency of bacteriuria among pregnant and non-pregnant women appears to be similar, pyelonephritis and recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI) are more frequent in women during the pregnancy-puerperal cycle [3].

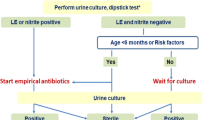

UTIs are classified into three subgroups: (a) asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB); (b) lower UTI, characterized by vaginal mucosa inflammation and irritative urinary tract symptoms; and (c) acute pyelonephritis or upper UTI, a systemic condition. In addition, UTIs can be classified as simple or complicated, depending on the presence of kidney and ureter involvement [4].

Urinary tract dilation and ureteral smooth muscle relaxation during pregnancy increase the susceptibility of the urinary tract to microorganisms. The implementation of universal screening for bacteriuria during pregnancy has substantially reduced the incidence of pyelonephritis; thus, urine culture should be routinely requested for all pregnant women at their first prenatal visit [5,6,7].

Bacterial colonization of the urinary tract during pregnancy may also be associated with adverse perinatal outcomes such as prematurity [8, 9], low birth weight [10], premature rupture of ovular membranes, and hypertensive syndromes [11,12,13]. Treating bacteriuria can mitigate some of these adverse obstetric outcomes.

Notably, there are substantial discrepancies in data regarding the prevalence of bacteriuria during pregnancy. In 2019, Latin America recorded the highest regional UTI incidence globally (13,852.9 cases per 100,000 population), the highest mortality from UTI (10.0 per 100,000 population), and the highest number of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) secondary to UTI (171.3 per 100,000 population) [14]. However, these aspects have been poorly explored in pregnant Latin American women, encouraging the present systematic review with meta-analysis.

The present systematic review would help plan public policies and the implementation of measures to optimize perinatal outcomes related to urinary tract infections during pregnancy.

Methods

Study protocol and selection

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. The studies were selected independently by two reviewers (MAKG and HD). Disagreements regarding study inclusion or exclusion were resolved through discussions until a consensus was reached. This systematic review is registered at PROSPERO (No. CRD42020212601).

Search strategy

The researchers systematically searched Medline/PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, and Bireme/Lilacs electronic databases, as well as the Google Scholar search engine. Studies published up to September 2022 were deemed eligible. The studies were searched using the following keywords alone or in combination: bacteriuria OR urinary tract infection OR pyelonephritis OR cystitis OR asymptomatic bacteriuria OR bacteriuria in pregnancy OR urinary tract infection in pregnancy OR pyelonephritis in pregnancy OR cystitis in pregnancy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: observational studies regarding the prevalence of bacterial urinary tract colonization in pregnant women from Latin American countries; objective diagnostic criteria for UTI, including urine culture reports with minimum bacterial growth of 1 × 105 CFU/ml in a midstream urine sample or of 1 × 102 CFU/ml in a sample obtained by urinary catheterization; published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese; and reported relative risks (RRs) or odds ratios (ORs) or presented original datasets that allowed the calculation of these association measures. This systematic review only included studies conducted in the 20 most populous countries in Latin America, according to the 2020 United Nations Statistical Division: Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Peru, Venezuela, Chile, Guatemala, Ecuador, Bolivia, Haiti, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Honduras, Paraguay, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Panama, and Uruguay [15]. Exclusion criteria were as follows: non-pregnant women; women residing in non-Latin American countries; incomplete information, such as the absence of prevalence data; duplicate studies; case reports or review articles or secondary analyses; or qualitative studies.

Data extraction

Two investigators (MAKG and HD) independently extracted relevant data from the studies using a standardized form. The retrieved data included first author details, year of publication, study demographic coverage area, study design, sample size, the prevalence of bacteriuria, the prevalence of UTI, diagnostic criteria for bacteriuria, and association measures such as RRs or ORs. In addition, information on the frequency of microorganism isolation in urine cultures of pregnant women was extracted.

Quality assessment

Considering the quality, the studies were classified according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines, analyzing five dimensions: sample population, sample size, percentage of participation among those eligible, result evaluation, and analysis of statistical methods employed. Each of these dimensions received a score ranging from 0 to 2 points. The final total score ranged from 0–10 points, with 10 representing the lowest overall risk of study bias and 0 representing the highest overall risk of study bias [16, 17].

Statistical analysis

Study-specific synthesized estimates were pooled using the random-effects meta-regression model to estimate the overall prevalence across studies after stabilizing the variance of individual studies using the Freeman-Tukey double-arcsine transformation [18]. Heterogeneity between study results was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and the I2 index. Publication bias was measured by reviewing the funnel plots and using Begg’s and Egger’s tests. The random-effects model was used to combine highly heterogeneous data. The adjusted ORs and 95%CI of included studies were used for data analysis. Study results were combined to produce a pooled OR-95%CI. Statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical software. Statistical significance was set as p < 0.05.

Results

Search results

Initial database and manual searches identified 253,550 citations (Medline/PubMed, 267; Google Scholar, 252,446; Lilacs/Bireme, 119; and Embase, 718). Studies were selected by title and abstract, resulting in the exclusion of 253,315 irrelevant studies. Of the remaining 235 citations, 27 were removed as duplicates. Thus, 208 full-text citations were evaluated for eligibility, with 141 excluded owing to unclear assessment methods or uncertain bacteriuria definitions (n = 63); non-Latin American pregnant women (n = 30); incomplete information (n = 24); qualitative studies, review articles, or case reports (n = 24). Overall, 67 citations published until September 2022 met the established inclusion criteria and were included in the present systematic review (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The present systematic review with meta-analysis included 67 articles, comprising 111,249 pregnant women from 9 Latin American countries (Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Guatemala, Paraguay, Peru, Mexico, and Venezuela) (Table 1). All included studies were cross-sectional in design, including 44 published articles, one doctoral dissertation, two master’s theses, and 20 undergraduate course papers. The sample size of the included studies ranged from 34–32,641 pregnant women [19, 20]. The largest number of studies were conducted in Brazil [20], followed by Peru [16] and Mexico [10]. No studies conducted in Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Panama, or Uruguay were selected. The lowest prevalence of bacteriuria was 1.78%, recorded in Mexico, and the highest was 56%, documented in Brazil [1, 19]. Studies reporting the presence of irritative urinary tract symptoms showed that the lowest prevalence of ASB was 1.57% in Ecuador, while the highest was 20.83% in Mexico. The lowest rate of cystitis was 3.1% (Mexico), and the highest was 20.9% (Peru) [21,22,23,24,25].

The overall prevalence of ASB, lower UTI, and pyelonephritis

The heterogeneity rate for ASB prevalence was high (I2 = 99.5%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of ASB in Latin American pregnant women was 18.39% (95% CI: 15.45–21.53) (Figs. 2 and 3) [1, 2, 19,20,21, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. Egger's linear regression test was performed to evaluate the asymmetry of the funnel plot, revealing no statistical significance (p = 0.767) (Available in Supplementary Material – Suppl 1).

The heterogeneity rate for lower UTI prevalence was high (I2 = 86.5%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of lower UTI in Latin American pregnant women was 7.54% (95%CI: 4.76–10.87) in 10 studies comprising 5,781 participants [21, 23,24,25, 35, 38, 47, 49, 81, 86]. Egger’s linear regression test to evaluate the asymmetry of the funnel plot showed statistical significance (p = 0.038) (Available in Supplementary Material – Suppl 2).

The heterogeneity rate for the prevalence of pyelonephritis was high (I2 = 88.4%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of pyelonephritis in Latin American pregnant women was 2.34% (95% CI: 0.68–4.85) in five studies comprising a sample size of 4,349 participants (Figs. 4) (Available in Supplementary Material – Suppl 3) [21, 25, 35, 81, 88].

Specific subgroups underwent additional analyses to reduce sample heterogeneity and enhance clinical and public health applicability.

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of ASB in articles comprising more than 500 participants

Studies with a larger sample underwent an initial analysis to reduce sample size biases. However, the heterogeneity rate for the prevalence of ASB in Latin American articles with more than 500 participants was also high (I2 = 99.2%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of ASB in Latin American pregnant women was 13.11% (95% CI: 8.42–18.65) in 15 studies comprising 23,782 participants, which was lower than the previous global rate (Fig. 2) (Available in Supplementary Material – Suppl 4) [1, 31, 35, 41, 45, 65,66,67,68,69, 71, 80,81,82, 84]. Egger’s linear regression test, performed to evaluate the asymmetry of the funnel plot, revealed statistical significance (p = 0.02), i.e., persistent publication bias (Supplementary Material – Suppl 5).

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of ASB in published Latin American articles, except Brazilian articles

The heterogeneity rate for the prevalence of ASB in the Latin American articles, except the Brazilian articles, was high (I2 = 98.6%, p < 0.05). The prevalence of ASB in Latin American pregnant women was 14.97% (95% CI: 11.10–19.28) in 26 studies comprising 20,896 participants (Supplementary Material – Suppl 6) [1, 27,28,29,30,31, 38, 41, 45,46,47, 51, 55,56,57, 61, 66,67,68, 71, 72, 80,81,82,83, 85]. Egger’s linear regression test to evaluate the asymmetry of the funnel plot showed statistical significance (p = 0.015).

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of ASB in Latin American articles (published or unpublished) with a sample of at least 200 participants, except for Brazilian articles

The heterogeneity rate for the prevalence of ASB in the Latin American articles with a sample of at least 200 participants, except for Brazilian articles, was high (I2 = 99.8%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of ASB in Latin American pregnant women, except Brazilian women, was 12.62% (95% CI: 9.26–16.40) (Supplementary Material – Suppl 7) [1, 20, 21, 24, 26, 29,30,31, 34, 38, 41, 45,46,47, 51, 55,56,57, 59, 61, 66,67,68, 70,71,72,73,74,75, 79,80,81,82,83, 85, 87, 89]. Egger’s linear regression test to evaluate the asymmetry of the funnel plot showed statistical significance (p = 0.015) (Supplementary Material – Suppl 8).

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of ASB considering only Brazilian articles (published or unpublished)

Considering only Brazilian articles, the heterogeneity rate for the prevalence of ASB was high (I2 = 97.5%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of ASB in Brazilian pregnant women was 23.62% (95% CI: 18.0–29.74) (Figs. 4 and 5) [2, 19, 23, 35, 37, 39, 40, 42,43,44, 48, 53, 54, 60, 65, 69, 76,77,78, 84, 86]. Egger’s linear regression test to evaluate the asymmetry of the funnel plot showed no statistical significance (p = 0.831) (Supplementary Material – Suppl 9).

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of ASB considering only Brazilian articles (published or unpublished) with a sample of at least 200 participants

Considering only Brazilian articles (published or unpublished), the heterogeneity rate for the prevalence of ASB was high (I2 = 98.7%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of ASB in Brazilian pregnant women was 19.05% (95% CI: 13.18–25.70) in 10 studies comprising 18,137 participants (Supplementary Material – Suppl 10) [2, 35, 37, 42, 43, 53, 65, 69, 76, 84, 86, 90]. Egger’s linear regression test to evaluate the asymmetry of the funnel plot showed no statistical significance (p = 0.595) (Supplementary Material – Suppl 11).

Isolated bacteria

In the present systematic review with meta-analysis of 67 studies, we examined the profile of microorganisms isolated in positive urine cultures of pregnant women residing in the 20 most populous countries in Latin America, comprising a sample of 8,840 urine cultures (Table 2). The most frequently isolated bacterial species in Latin American pregnant women were Escherichia coli (pooled prevalence of 70%, 95% CI: 65.3–74.6%); Klebsiella sp. (pooled prevalence of 6.4%, 95% CI: 4.3–8.7%); Staphylococcus sp., excluding Staphylococcus aureus, (pooled prevalence of 3.0%, 95%CI: 1.7%–4.5%); Proteus mirabilis (pooled prevalence of 2.8%, 95% CI: 1.9–3.9%); and Enterobacter sp. (pooled prevalence of 1.6%, 95% CI: 0.7–2.7%) (Supplementary Material – Suppl 12–21).

Discussion

Based on the present meta-analysis, the frequency of ASB in Latin American pregnant women was 18.39% (95% CI: 15.45–21.53). This prevalence is higher than frequencies reported in international meta-analyses, including those from Ethiopia (15.37%), Africa (11.1%), and Iran (8.7%) [125,126,127].

Despite the current propensity to prevent unnecessary antibiotic use, screening and treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria have become routine in almost all prenatal care guidelines. This occurs because, when the incidence of bacteriuria reaches values greater than 2%, the cost-effectiveness of universal screening appears to be adequate to prevent the occurrence of pyelonephritis during pregnancy [128, 129]. Our study demonstrated a high prevalence of bacteriuria among pregnant Latin American women, reinforcing the importance of universal screening for bacterial colonization of the urinary tract in this population.

In a broad worldwide study in 2019, Tropical Latin America had the highest worldwide UTI incidence standardized by age, with approximately 13,852.9 cases per 100,000 population. Notably, Ecuador presented the highest incidence of UTI globally, with approximately 15,511.3 cases per 100,000 population. In 2019, a global analysis of UTI revealed that the highest mortality rate was recorded in southern Latin America (10 deaths per 100,000 population), and the highest number of DALYs lost was recorded in Tropical Latin America (171.3 per 100,000 population) [14]. Evaluating women only, the highest regional incidences are found, in descending order, in Andean Latin America, Tropical Latin America, Australasia, the Caribbean, and southern Latin America. In 2019, over 404 million individuals had UTIs, with over 236,000 UTI-related deaths recorded [14].

Between 1990 and 2019, the global UTI incidence rate adjusted for age increased from 4,715 to 5,229 per 100,000 population, with the global death rate due to UTI increasing from 1.8 to 3.1 per 100,000 population. A comparison between three-decade-old and current data revealed an absolute increase of approximately 130,000 UTI-related deaths. Over the past three decades, the largest estimated annual percentage changes in UTI incidence rates were observed in Central Latin America (0.48, 95% CI: 0.29–0.67) and Andean Latin America (0.45, 95% CI: 0.4–0.51), and the highest estimated annual percentage changes in UTI mortality rates were documented in southern Latin America (4.92, 95% CI: 4.26–5.59) and Tropical Latin America (3.50, 95% CI: 3.14–3.87). Given the impact of bacterial urinary tract colonization on public health outcomes and the highest global percentage of bacteriuria prevalence documented in Latin America, it is crucial to further explore this topic [14, 130].

Bacteriuria is associated with some adverse perinatal outcomes. Antimicrobial treatment of bacteriuria can reduce the incidence of pyelonephritis in pregnant women (RR 0.24, 95% CI = 0.13–0.41; 12 studies, 2017 women), premature birth (RR 0.34, 95% CI = 0.13–0.88; 3 studies, 327 women) and low birth weight (RR 0.64, 95% CI = 0.45–0.93; 6 studies, 1437 newborns) [131]. There is also evidence that urinary tract infection during pregnancy corresponds to a risk factor for the occurrence of pre-eclampsia (OR 1.31; 95% CI = 1.22–1.40) [13]. The increase in the global mortality rate from UTI in the last three decades, associated with unfavorable obstetric results related to the diagnosis of bacteriuria, reinforces the importance of our study.

Based on the present study, E. coli was the most frequently isolated uropathogen in the urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. The results of this meta-analysis corroborate documented findings in the literature, with up to a 95% frequency of E. coli noted among the total number of bacteria isolated from the urinary tract [3].

Considering the total number of uropathogens, the second most isolated bacterial species belonged to the Enterobacteriaceae family (Klebsiella sp. or Proteus sp.) [3]. The present review revealed that Klebsiella sp. was the second most frequently isolated bacterial species among Latin American pregnant women (pooled prevalence of 6.4%, 95% CI: 4.3–8.7), followed by Proteus mirabilis as the fourth most frequently identified species in urine cultures (pooled prevalence of 2.8%, 95% CI: 1.9–3.9) and Enterobacter sp. as the fifth (pooled prevalence of 1.6%, 95% CI: 0.7–1.7).

This meta-analysis supports previously reported findings regarding the frequency of Streptococcus agalactiae among the total number of uropathogens. Collin et al. have analyzed the prevalence of Lancefield group B Streptococcus in non-invasive bacterial infections worldwide. The authors identified UTI prevalence rates of 1.61% among bacterial isolates collected from the community and 0.72% among UTI bacterial isolates collected from a hospital environment [132].

Although the present systematic review with meta-analysis presents up-to-date evidence on the prevalence of bacteriuria in Latin American pregnant women, the limitations should be addressed. First, the lack of studies in southern Latin America and Central America may hinder generalization, warranting further investigation of UTIs in these regions. Second, there was significant heterogeneity in the overall pooled prevalence analysis of bacteriuria in Latin American pregnant women, a characteristic maintained in almost all subgroup analyses. Third, we noted a significant publication bias in the general assessment of the prevalence of bacteriuria among pregnant women, both in funnel plots and Egger’s test, reinforcing the need for careful data interpretation. The inclusion of non-published studies in the sub-analyses helped reduce this bias.

Our systematic review with meta-analysis included a total of 67 studies. Of this total research, more than a third had not been published. Of the articles published, only a few were selected in journals indexed in the main international databases. Although bacteriuria is a common topic in obstetric clinical practice, available data on Latin American pregnant women were scarce or difficult to obtain and, according to our review, at rates much higher than those from other regions and indicated by other previous studies, strengthening the value of our current research.

In our study we also examined the profile of microorganisms isolated in positive urine cultures from pregnant women living in the 20 most populous countries in Latin America. This information can help in the construction of care protocols guided by the local bacterial profile, favoring treatments with lower-cost antimicrobials. There are still limitations to Latin American pregnant women's access to health services. In the most populous country in the region, Brazil, in 2021, only two thirds (76.55%) of women had access to adequate prenatal care, that is, starting in the first trimester of pregnancy and with at least six outpatient consultations [133]. Therefore, considering the deficiencies in access to health professionals and laboratory tests during pregnancy, knowledge of the bacterial colonization profile of pregnant women in Latin America can help in planning care for this population.

Conclusion

UTI and asymptomatic bacteriuria are markedly common among Latin American pregnant women. The prevalence of bacteriuria among Brazilian pregnant women tends to be higher than the mean of Latin America or other regions worldwide. These results reinforce the need for universal screening with urine culture during early prenatal care. Evidence supporting repeated screening for bacteriuria during different trimesters or gestational ages is lacking. Among Latin American pregnant women, the most common microorganism in the etiology of bacteriuria was E.coli. Another frequently isolated uropathogen was S. agalactiae, with a higher prevalence than that reported in other international studies. This information is highly relevant, as maternal colonization with Lancefield group B streptococci has been associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, such as neonatal sepsis. Given the higher frequency of UTI among Latin American pregnant women, additional studies are needed to assess the effectiveness of screening protocols and better identify the different microbial sensitivity profiles of uropathogens isolated from these women.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- ASB:

-

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

- DALY:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RR:

-

Relative risks

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

References

Medic CV, Villegas MRL, Guerra MAE, Valverde BR. Urinary tract infections prevalence in pregnant women attended at the Hospital Universitario de Puebla. Enferm Infecc Microbiol. 2010;30(4):118–22.

Santos FS, Souza AN, Bezerra JM, Arrais FA, Santos S, Gomes A, et al. Profile socio-demographic, birth and morbidity of pregnant women attended in a primary health care. J Dev Res. 2018;8(2):18890–3.

Urinary tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy - UpToDate. Cited 2022 Mar 4. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/urinary-tract-infections-and-asymptomatic-bacteriuria-in-pregnancy?search=asymptomatic%20bacteriuria%20pregnancy&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~73&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.

Zugaib MFR. Zugaib obstetrícia. 4th ed. São Paulo: Manole; 2019. p. 1424.

Wingert A, Pillay J, Featherstone R, et al. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Edmonton: Evidence Review and Synthesis Centre, Univerity of Alberta; 2017.

Wingert A, Pillay J, Sebastianski M, Gates M, Featherstone R, Shave K, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy: systematic reviews of screening and treatment effectiveness and patient preferences. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e02134.

Moore A, Doull M, Grad R, Groulx S, Pottie K, Tonelli M, et al. Recommendations on screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. CMAJ. 2018;190(27):E823–30.

Wren BG. The value of leucocyte excretion rates in determining “at risk” patient with asymptomatic bacilluria. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1971;78(2):130–5.

Henderson M, Entwisle G, Tayback M. Bacteriuria and pregnancy outcome: preliminary findings. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1962;52(11):1887–93.

Smaill FM, Vazquez JC. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD000490.

Kincaid-Smith P, Bullen M. Bacteriuria in pregnancy. Lancet. 1965;285(7382):395–9.

Stuart KL, Cummins GTM, Chin WA. Bacteriuria, prematurity, and the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Br Med J. 1965;1(5434):554.

Yan L, Jin Y, Hang H, Yan B. The association between urinary tract infection during pregnancy and preeclampsia: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97:36.

Zeng Z, Zhan J, Zhang K, Chen H, Cheng S. Global, regional, and national burden of urinary tract infections from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. World J Urol. 2022;40:755–63.

UNdata. Cited 2022 Oct 14. Available from: http://data.un.org/.

Song P, Zhang Y, Yu J, Zha M, Zhu Y, Rahimi K, et al. Global prevalence of hypertension in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(12):1154.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbrouckef JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(11):867.

Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(11):974–8.

Pagnonceli J, Abegg MA, Colacite J. Avaliação de infecção urinária em gestantes do município de Marechal Cândido Rondon – PR. Arquivos Ciênc Saúde UNIPAR. 2010;14(3):211–6.

Poma Zapana JH. Infección urinaria materna y sus riesgos materno perinatales en el Hospital Hipólito Unanue de Tacna 2009 – 2018. 2019. p. 101. Tesis (Título de Médico Cirujano) - Universidad Nacional Jorge Basadre Grohmann, Tacna, Perú.

Macías JS. Infección de vías urinarias durante el embarazo: factores de riesgo. Propuesta de guía educativa para su prevención. 2016. p. 76. Trabajo de Titulación (Grado de Magister em gerencia Clinica em Salud Sexual y Reproductiva) – Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Romero Macías LL. Infecciones de vias urinarias, factores de riesgo y complicaciones en embarazadas de 18 a 25 años, estudio a realizarse en el Hospital Teodoro Maldonado Carbo período 2014 - 2015. 2016. Cited 2021 Oct 28. Available from: http://repositorio.ug.edu.ec/handle/redug/35817.

Quiroga-Feuchter G, Robles-Torres RE, Ruelas-Morán A, Gómez-Alcalá AV. Asymptomatic bacteriuria among pregnant women. An underestimated threat. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2007;45(2):169–72.

Martínez González JÁ. Incidencia de gérmenes en urocultivos en pacientes adolescentes embarazadas en Hospital Alta Especialidad en Veracruz. 2019. p. 29. Tesis (Posgrado em Ginecologia e Obstetricia) – Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz, México.

Gonzales IG. Factores de riesgo asociados en la infección del tracto urinario en gestantes atendidas en el Centro de Salud Talavera – Provincia Andahuaylas. Abril – Junio 2017. 2017.p. 89. Tesis (Licenciatura em Obstetricia) – Universidad Alas Peruanas, Abancay, Perú.

Morán AL, Angarita JS, Castañeda AL. Bacteriuria asintomática en el embarazo. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 1990;41(1):13–23.

Pacheco J, Flores T, García M. Contribución al estudio de la prevalencia de la bacteriuria asintomática en gestantes. Rev Peruana Ginecol Obstet. 1996;42(2):39–43.

Ginestre M, Martínez A, Fernández M, Alaña F, Castellano M, Romero S, Rincón G. Bacteriuria asintomática en mujeres embarazadas: frecuencia y factores de riesgo. Kasmera. 2001;29(2):171–83.

Cárdenas HFM, Ardila LYA, Prada MNCS, Rico MLT, Parra ARV. Prevalencia de bacteriuria asintomática en embarazadas de 12 a 16 semana de gestación. Med UNAB. 2005;8(2):78–81.

Teppa RJ, Roberts JM. The uriscreen test to detect significant asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12(1):50–3.

Hernández Blas F, López Carmona JM, Rodríguez Moctezuma JR, Peralta Pedrero ML, Rodríguez Gutiérrez RS, Ortiz Aguirre AR. Asymptomatic bacteruiria frequency in pregnant women and uropathogen in vitro antimicrobial sensitivity. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2007;75(6):325–31.

Sánchez Villasante E. Factores de riesgo para bacteriuria asintomática durante la gestación en el Instituto Especializado Materno Perinatal, y el año 2004. 2005. p. 32. Tesis (Posgrado en Ginecologia y Obstetricia) - Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru.

Feitosa DCA. Infecções do trato urinário e do trato genital inferior em gestantes de baixo risco do município de Botucatu/SP. Aleph; 2008. p. 105. Available from: https://repositorio.unesp.br/handle/11449/104861.

Sotero Neciosup VE. Prevalencia, Factores De Riesgo Y Patógenos Asociados A Bacteriuria Asintomática Según Trimestre De Gestación. Hospital De Apoyo Chepén. 2009. p. 58. Tesis (Bachiller en Medicina) - Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Trujillo, Peru.

Vasconcelos Pereira EF, Figueiró Filho EA, de Marcon Oliveira V, Claudia A, Fernandes O, de Santos Moura Fé C, et al. Urinary tract infection in high risk pregnant women. J Trop Pathol. 2013;42(1):21–9.

Santana Mera LJ. Perfil de Resistencia Bacteriana de Infecciones Urinarias en Pacientes Embarazadas Atendidas en el Servicio de Ginecología y Obstetricia del Hospital Provincial General Docente Riobamba Durrante el Periodo Enero - Diciembre 2008. 2009. p. 78. Tesis (titulo de Médico general) – Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo, Riobamba, Ecuador.

Darzé OISP, Barroso U, Lordelo M. Clinical predictors of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2011;33(8):196–200.

Valdivieso FDL. Microorganismos que provocan infección de vías urinarias en mujeres en período de gestación y su resistencia en el Hospital Carlos Andrade Marín en el período mayo 2011 - septiembre 2011. 2012. p. 81. Tesis (título de Médico Cirujano) - Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador.

Giraldo PC, Arajo ED, Junior JE, do Amaral RL, Passos MRL, Gonaçlves AK. The prevalence of urogenital infections in pregnant women experiencing preterm and full-term labor. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:878241.

de Guerra GV, de Souza ASR, da Costa BF, do Nascimento FRQ, de Amaral MA, Serafim ACP. Exame simples de urina no diagnóstico de infecção urinária em gestantes de alto risco. Rev Br Ginecol Obstet. 2012;34(11):488–93.

Mendieta A, Morales M. Bacteriuria Asintomática durante el embarazo, estudio de prevalencia en el Hopital “José Carrasco Arteaga. Rev Méd HJCA. 2012;4(2):133–133.

Vettore MV, Dias M, Vettore MV, do Leal MC. Assessment of urinary infection management during prenatal care in pregnant women attending public health care units in the city of Rio de Janeiro Brazil. Rev Br Epidemiol. 2013;16(2):338–51.

Farias RAR. Morbidades na gravidez associadas ao nascimento pré-termo em São Luís/MA. 2013. p. 99. Dissertação (Mestrado em Enfermagem) – Universidade Federal do Maranhão, São Luís, Maranhão.

Barros SRAF. Infecção urinária na gestação e sua correlação com a dor lombar versus intervenções de enfermagem. Revista Dor. 2013;14(2):88–93.

Corral Anduaga JA, González Orduño JF, Corral Anduaga JA, González Orduño JF. Índice de infección en el tracto urinario de mujeres embarazadas atendidas en el Hospital General de Bajo Río Mayo de Huatabampo, en el período comprendido de julio 2011 a junio 2012. 2013. p. 78. Tesis (Título de Químico Biólogo) – Universidad de Sonora, Sonora, México.

Maroto Llerena GE. Etiología y resistencia bacteriana en infección de vías urinarias en pacientes embarazadas atendidas en el servicio de hospitalización de ginecología y obstetricia del hospital provincial general puyo durante el período de marzo-agosto 2012. 2013.p. 88. Tesis (Título de Médico) – Universidad Técnica de Ambato, Ambato, Ecuador.

Vargas JE, Torres LG, Concha YL. Infección urinaria y gestación centro de Salud ampliación Paucarpata. Veritas J. 2013;13(1):208–16.

Alves CN, Wilhelm LA, Bublitz S, Bisognin P, Barreto CN, Ressel LB. Gynaecological-obstetric profile of pregnant women assisted in consultation of prenatal low risk. J Nurs UFPE Online. 2014;8(7):3059–68.

Salazar JCG. Frecuencia de la infección de vías urinarias en pacientes en el tercer trimestre del embarazo del centro especializado de atención primaria de la salud Santa María Rayón, México de agosto 2013 a febrero 2014. 2014. p. 46. Tesis (Licenciatura en Médico Cirujano) – Universidad Autônoma del Estado de México, Toluca, México.

Castillo DEF. Características epidemiológicas clínicas y etiológicas de la infección del tracto urinario en gestantes atendidas en el Hospital Regional EsSalud III José Cayetano Heredia Piura. 2015. 54f. Tesis (posgrado en Médico Cirujano) – Universidad Nacional de Piura, Piura, Peru.

Pérez WSF. Incidenca de Infección Urinaria en gestantes atendidas en el Hospital Provincial Docente Belen de Lambayeque. Julio – Setiembre 2015. 2015. p. 44. Tesis (Licenciatura en Biologia, Microbiologia y Parasitologia) – Universidad Nacional Pedro Ruiz Gallo, Lambayeque, Peru.

Orozco Vega RV. Determinación de bacteriuria asintomática y su relación con infección de vías urinarias en mujeres gestantes que acuden al centro de salud tipo a de la Ciudad de la Joya de los Sachas. 2015. Trabajo de finalización del curso – Universidad Tecnica de Ambato, Ambato, Ecuador.

Ramos GC, Laurentino AP, Fochesatto S, Francisquetti FA, Rodrigues AD. Prevalência de infecção do trato urinário em gestantes em uma cidade no sul do Brasil. Saúde (Santa Maria). 2016;42(1):173–8.

de Oliveira RA, Ribeiro EA, Gomes MC, Coelho DD, Tomich GM. Perfil de suscetibilidade de uropatógenos em gestantes atendidas em um hospital no sudeste do Estado do Pará Brasil. Rev Panamazonica Saude. 2016;7(3):8–8.

Autún Rosado DP, Sanabria Padrón VH, Cortés Figueroa EH, Rangel Villaseñor O, Hernández-Valencia M. Etiología y frecuencia de bacteriuria asintomática en mujeres embarazadas. Perinatol Reprod Hum. 2015;29(4):148–51.

Alvarado ET, Rubio MAS. Prevalencia de bacteriuria en pacientes embarazadas de una unidad de medicina familiar del Estado de México. Atención Familiar. 2016;23(3):80–3.

Solomán ASPH, Salazar GGP. Prevalencia de bacteriuria asintomática en adolescentes gestantes y factores de riesgo associados. 2016. p. 78 f. Tesis – Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala.

Mantilla ADC. Infección de las vías urinarias bajas, causas y complicaciones durante el primer trimestre de embarazo, a realizarse en el Hospital Naval de Guayaquil período 2014–2015. 2016. p. 49. Tesis (título de Médico) – Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Soria JMB. Infección de vías urinarias, factores de riesgo y complicaciones en embarazadas de 15 a 35 años Area Ginecología Hospital Alfredo Noboa : período 2015. 2016. p. 46. Trabajo de Titulación (Título de Médico) – Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Santos AMA. Histórico de intercorrências na gestação de mulheres residentes na Cidade Estrutural, Distrito Federal, 2017. 2017. p. 22. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Graduação em Enfermagem) – Centro Universitário de Brasília, Brasília, Distrito Federal.

Campo-Urbina ML, Ortega-Ariza N, Parody-Muñoz A, Gómez-Rodríguez LD. Characterization and susceptibility profile of uropathogens associated with the presence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women in the department of Atlántico, Colombia 2014–2015. Cross-sectional study. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2017;68(1):62–70.

Maquera DJM. Complicaciones obstétricas y perinatales en las gestantes adolescentes atendidas en el hospital nacional Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen durante el periodo enero – julio del año 2016. 2017. p. 121 . Tesis (Posgrado en Médico Cirujano) - Universidad Nacional Jorge Basadre Grohmann, Tacna, Peru.

Flores YJ. Frecuencia de infección del tracto urinario en mujeres gestantes que asisten a consulta prenatal al Hospital Víctor Lazarte Echegaray Trujillo. Julio –Diciembre 2016. 2017. p. 48. Tesis (Licenciatura Tecnologo Medico) – Universidad Alas Peruanas, Trujillo, Perú.

Melendres AF. Frecuencia y factores de riesgo asociados a bacteriuria asintomática en gestantes atendidas en el Hospital Referencial de Ferreñafe, Noviembre 2016. 2017. p. 56. Tesis (Título de Médico Cirujano) – Universidad Particular de Chiclayo, Chiclayo, Perú.

Santos CC, Madeira HS, Silva CM, Teixeira JJV, Peder LD. Prevalência de infecções urinárias e do trato genital em gestantes atendidas em Unidades Básicas de Saúde. Rev Ciênc Méd. 2018;27(3):101–13.

Quirós-Del Castillo AL, Apolaya-Segura M. Prevalence of urinary tract infection and microbiological profile in women who end their pregnancy in a private clinic in Lima Peru. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2018;86(10):634–9.

Villantoy Sanchez LM. Prevalencia de infección del tracto urinario en gestantes del Distrito de Huanta, 2016. 2017. p. 59. Tesis (Especialista em Emergencias y Alto Riesgo Obstétrico) – Universidad Nacional de Huancavelica, Huancavelica, Perú.

Bello-Fernández Z, Cozme-Rojas Y, Pacheco-Pérez Y, Gallart-Cruz A, Bello-Rojas A. Resistencia antimicrobiana en embarazadas con urocultivo positivo. Revista Electrónica Dr. Zoilo E. Marinello Vidaurreta [Internet]. 2018 [cited 20 Oct 2023];43(4). Available from: https://revzoilomarinello.sld.cu/index.php/zmv/article/view/1433.

Pancotto C, von Lovison OA, Cattani F. Perfil de resistência, etiologia e prevalência de patógenos isolados em uroculturas de gestantes atendidas em um laboratório de análises clínicas da cidade de Veranópolis, Rio Grande do Sul. Rev Br Anál Clín. 2019;51(1):29–33.

Cconislla YLG. Características epidemiológicas, clínicas y microbiológicas de la infección del tracto urinario en gestantes atendidas en el Hospital Nacional Adolfo Guevara Velasco Essalud-Cusco, 2018. 2019. p. 70. Tesis (Título de Médico Cirujano) - Universidad Andina del Cusco, Cusco, Perú.

Díaz IBAG. Incidencia y factores de riesgo en infecciones del tracto urinario en embarazadas de 12 a 35 años atendidas en el Hospital Regional Docente de Cajamarca durante el año 2018. 2019. p. 70. Tesis (Título de Médico Cirujano) - Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Cajamarca, Perú.

Chamoly FR. Frecuencia y sensibilidad antimicrobiana de bacterias causantes de itu en gestantes atendidas en el centro de salud Huanchaco durante agosto - noviembre 2018. 2019. p. 60. Tesis (Título Profesional em Laboratorio de Analisis Clinico y Biologicos) - Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Trujillo, Perú.

Placencia DLA. Prevalencia y factores asociados a infección del tracto urinario en gestantes hospitalizadas en el área de ginecología del Hospital Homero Castanier Crespo. Azogues. Enero a diciembre de 2018. 2019. p. 65. Trabajo de Graduación (título de Médico) - Universidad Católica de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador.

Mandujano JCG. Frecuencia de bacteriuria asintomática, uropatógenos asociados y sensibilidad antimicrobiana in vitro en pacientes que acuden a control obstétrico en el hospital de la mujer durante el período de enero a diciembre del 2016. 2020. p. 73. Tesis (Posgrado en Ginecologia y Obstetricia) – Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca, Morelos, México.

Fretes MS, Fretes NE, Villagra AR, Galeano A, Oviedo RV, Cruz FVS. Infección urinaria en embarazadas que asisten al consultorio externo del hospital materno infantil santísima trinidad. Asunción, Paraguay. Anal Facultad Cienc Méd (Asunción). 2020;53(1):31–40.

Cabús CG. Agentes etiológicos bacterianos de infecção do trato urinário em gestantes da rede pública de Manaus. 2021. 58 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências da Saúde) - Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, Amazonas.

Rhode S, dos Santos JC, Dam RI, Ferrazza MHSH, Tenfen A. Prevalence of urinary infection in pregnant women attended by a basic health unit in Jaraguá do Sul, SC - Brazil. Br J Dev. 2021;7(1):7035–47.

Filho ES, de Vieira HRAL, do Castro FFS. Bacterial profile and resistance to standard antibiotics in pregnant women with symptomatic and asymptomatic bacterial in the federal district. Br J Health Rev. 2021;4(5):20765–78.

Macías JA. Frecuencia de infección de vías urinarias en el embarazo y el apego a guía de práctica clínica en la UMF2. 2021. p. 66f. Tesis (Posgrado em Medicina Familiar) – Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Puebla, México.

Ruiz-Rodríguez M, Sánchez-Martínez Y, Suárez-Cadena FC, García-Ramírez JC, Ruiz-Rodríguez M, Sánchez-Martínez Y, et al. Prevalence and characterization of urinary tract infection in socially vulnerable pregnant women in Bucaramanga, Colombia. Rev Facultad Med. 2021;69(2):e77949.

la Hoz FJED. Infección Urinaria en Gestantes: Prevalencia y Factores Asociados en el Eje Cafetero, Colombia, 2018–2019. Colombian Urology Journal. 2021;30(02):098–104.

Sánchez-Álvarez M, Escobar-Martín H, Sánchez-Guerra Y, Molina-Linares I, Sánchez-Padrón G, Quesada-Ravelo O, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: diagnosis in pregnant women by oyron well d-one in primary health care, Villa Clara. Cuba Paideia XXI. 2021;11(1):31–42.

Planchez LC, et al. Gestantes con infección urinaria pertenecientes a un área de salud del municipio Guanabacoa La Habana. Ver Med Electrón. 2021;43(1):2748–58.

de Souza HD, Hase EA, Galletta MAK, Diorio GRM, Waissman AL, Francisco RPV, et al. Urinary bacterial profile and antibiotic susceptibility in pregnant adolescents and pregnant low obstetric risk adult women. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:2829.

Jerí M, Callahui R, Lam N. Bacteriuria asintomática en la gestante de altura. Rev Peruana Ginecol Obstet. 2007;53(2):135–9.

Feitosa DCA, da Silva MG, de Parada CMGL. Accuracy of simple urine tests for diagnosis of urinary tract infections in low-risk pregnant women. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2009;17(4):507–13.

Castillo DEF. Características epidemiológicas clínicas y etiológicas de la infección del tracto urinario en gestantes atendidas en el Hospital Regional EsSalud III José Cayetano Heredia Piura. 2015. p. 54. Tesis (Posgrado en Médico Cirujano) – Universidad Nacional de Piura, Piura, Peru.

de Zanatta DAL, de Rossini MM, Trapani Júnior A. Pielonefrite na gestação: aspectos clínicos e laboratoriais e resultados perinatais. Rev Br Ginecol Obstet. 2017;39(12):653–8.

Malberti González AA. Prevalencia de infección urinaria en embarazadas internadas en el servicio de ginecología obstetricia del Hospital Central del Instituto de Previsión Social, 2018. 2019. Trabajo de fin de grado – Universidad Nacional de Caaguazú, Coronel Oviedo, Paraguay.

Souza HD, Francisco RPV, Hase EA, Diório GRM, Waissman AL, Peres SV, et al. Bacteriuria in pregnant adolescents and behavioral risk factors: a cross-sectional study at a Brazilian teaching hospital. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2022;35(3):314–22.

Schenkel DF, Dallé J, Antonello VS, Schenkel DF, Dallé J, Antonello VS. Prevalência de uropatógenos e sensibilidade antimicrobiana em uroculturas de gestantes do Sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2014;36(3):102–6.

Pereira ÉFV. Aspectos diagnósticos, terapêuticos e complicações perinatais em gestantes de alto risco com infecção do trato urinário. 2010. Dissertação de mestrado -Universidade Federal do Mato Grosso do Sul, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil.

Souza RB. Sensibilidade bacteriana à fosfomicina em gestantes com infecção urinária. 2014. Dissertação de mestrado – Universidade do Sul da Santa Catarina, Santa Catarina, Brasil.

Aguirre Carvalho F, de Abreu RM, Bottega A, Hörner R. Prevalência e perfil de sensibilidade de bactérias isoladas da urina de gestantes atendidas no serviço de obstetrícia de um hospital terciário. Scientia Medica. 2016;26(4):5.

de Menezes FMC, de Guimarães BMA, dos Neto AGS, Alves LL, Pinheiro MS. Urinary tract infection in pregnant women: assessing uropatogen susceptibility to antimicrobials in positive urocultures. Br J Health Rev. 2020;3(6):17353–64.

Stella AE, de Oliveira AF. Padrões de resistência a antibióticos em enterobactérias isoladas de infecções do trato urinário em gestantes. Res Soc Dev. 2020;9(8):e862986337.

Arruda ACPMG, Marangoni PA, Tebet JLS. Sensitivity profile of uropathogens in pregnant women at a teaching hospital in the city of São Paulo. Femina. 2021;49(6):373–8.

Ferreira FE, Olaya SX, Zúñiga P, Angulo M. Infección urinaria durante el embarazo, perfil de resistencia bacteriana al tratamiento en el Hospital General de Neiva Colombia. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2005;56(3):239–43.

Francisco SR, José JH, Omar LG, Samuel CV. Antibiotic resistance of the germs which cause acute pyelonephritis in pregnancy. Rev Cienc Bioméd. 2012;3(2):260–6.

Herrera NAN. Incidencia de pielonefritis aguda en el embarazo, tasa de curación microbiológica y resultados maternos en la Clínica Foscal Floridablanca, Colombia. 2020. Trabajo de grado – Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga, Bucaramanga, Colombia.

Mora MCI, Bayona ABM. Infección de vías urinarias en gestantes : caracterización microbiológica y clínica en un hospital universitario, Bogotá (Colombia) 2016–2017. 2018. Trabajo de grado – Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia.

Arrieta JFQ. Perfil de resistencia antimicrobiana en infección del tracto urinario de embarazadas atendidas en una institución de la ciudad de Cartagena entre los años 2018 y 2019. 2020. Trabajo de grado – Universidad de Cartagena, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia.

Casas PRL, Ortiz M, Erazo-Bucheli D. The prevalence of ampicillin resistance in pregnant women suffering from urinary tract infections in the San josé Teaching Hospital. Popayán, Colombia 2007–2008. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2009;60(4):334–8.

Reyes-Hurtado A, Gómez-Ríos A, Rodríguez-Ortiz JA. Validez del parcial de orina y el Gram en el diagnóstico de infección del tracto urinario en el embarazo. Hospital Simón Bolívar, Bogotá, Colombia, 2009–2010. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2013;64(1):53–9.

Aguirre JD. Prevalencia de la resitencia a la ampicilina en gestantes con infección urinaria en el HTUU de Tuluá 2010–2011. 2013. Trabajo investigativo – Unidad Central del Valle del Cauca, Tuluá, Colombia.

Rodríguez Pereira JM, Luque Guerrero MI. Resistencia bacteriana al tratamiento de infecciones del tracto urinario en la gestación en una clínica de Santa Marta. 2018. Trabajo de investigación – Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia, Santa Marta, Colombia.

Sanin-Ramirez R, Calle-Meneses C, Jaramillo-Mesa C, Nieto-Restrepo JA, Marín-Pineda DM, Campo-Campo MN. Etiological prevalence of urinary tract infections in symptomatic pregnant women in a high complexity hospital in Medellín, Colombia, 2013–2015. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2019;70(4):243–52.

Mc´Nish Gordon DE, Rodríguez Toledo LV. Perfil de sensibilidad de patógeno identificado en urocultivosen mujeres gestantes en el Hospital Alfonso Jaramillo Salazar E.S.E. 2016. 2019. Trabajo de grado – Universidad del Tolima, Tolima, Peru.

Jaramillo LIJ, Aristizábal KJO, Londoño ACJ, Carvajal MCU. Perfil clínico y epidemiológico de gestantes con infección del tracto urinario y bacteriuria asintomática que consultan a un hospital de mediana complejidad de Antioquia (Colombia). Arch Med (Manizales). 2021;21(1):57–66.

Vásquez Del Aguila TG. Sensibilidad Antibiótica De Las Bacterias Causantes De Infecciones Del Tracto Urinario En Gestantes. Hospital Regional Docente De Trujillo 2007 - 2008. 2008. Trabajo de grado - Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Trujillo, Peru.

Rivera DV. Características microbiológicas y tratamiento de la gestante com infección del tracto urinario em el hospital Goyeneche, Arequipa – 2014. 2015. Tesis de Grado - Universidad Católica de Santa Maria, Arequipa, Peru.

Tafur Rivera YI. Determinación etiológica y sensibilidad antimicrobiana en infecciones del tracto urinario en gestantes atendidas en el hospital tingo maría, año 2016. 2018. Tesis - Universidad de Huánuco, Tingo Maria, Peru.

Montalvo Mayta SL. Frecuencia de microorganismos en infección urinaria en gestantes de altura en el Hospital Ramiro Prialé - Huancayo 2019. 2020. Tesis - Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú, Huancayo, Peru.

Paredes Reyes SI. Bacterias causantes de infecciones del tracto urinario y resistencia antibiótica en gestantes atendidas en el Hospital de Apoyo Chepén, La Libertad-Perú. 2019. Tesis - Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Trujillo, Peru.

Tordecilla Argel JV. Estudio de factores de riesgo del desarrollo de bacteriuria asintomática en embarazadas de 12 - 18 semanas de gestación Hospital Gineco-Obstétrico Enrique C. Sotomayor, 2009 - 2010. 2011. Trabajo de grado – Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Rodríguez Jaya NL. Prevalencia de infecciones del tracto urinario en mujeres atendidas en el centro de salud de Las Lajas. El Oro 2009 - 2011. Propuesta de medidas de prevención. 2014. Trabajo de grado – Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Albán Moreno HO. Salud sexual y reproductiva, bacteriuria asintomática en el embarazo y efectos perinatales en la Clínica La Providencia, programa de control. 2016. Trabajo de grado – Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Cevallos Piloso AM, Pinos Sarabia GJ. Incidencia de infecciones de las vías urinarias en gestantes de un centro de salud público de Guayaquil. 2017. Trabajo de grado – Universidad Católica de Santiago de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Gadvay Bonilla NM, Peñafiel Paliz JJ. Determinación de resistencia a antibióticos en mujeres embarazadas con diagnóstico de infección de vías urinarias. 2019. Trabajo de grado – Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Jiménez Martinetti YE, Rodríguez Villarreal IA. Incidencia de infecciones de las vías urinarias en gestantes de 15 a 19 años en un Centro de Salud de la ciudad de Guayaquil, desde octubre 2018 a febrero 2019. 2019. Trabajo de grado – Universidad Catolica de Santiago de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Mendoza Flores NL, Rodrigues ZA. Determinación de el perfil de resistencia bacteriana en Infecciones del Tracto Urinario de mujeres embarazadas, que acudieron a control prenatal en el servicio de bacteriología del Hospital Municipal Boliviano Holandés de enero a diciembre 2009. 2011. Tesina – Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, La Paz, Bolivia.

Abarzúa CF, Zajer C, Donoso B, Belmar JC, Riveros JP, González BP, et al. Reevaluacion de la sensibilidad antimicrobiana de patogenos urinarios en el embarazo. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol. 2002;67(3):226–31.

Alvarado, MMH. Factores de riesgo relacionados con la prevalencia de bacteriuria asintomática em el hospital “Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes” de Carhuaz. 2015. Tesis – Universidad Privada de Ica, Ica, Peru.

Moreira Ortega JA. Etiología y manifestaciones clínicas en las infecciones de vías urinarias, estudio a realizarse en pacientes de 20 a 40 semanas de gestación en el Hospital Teodoro Maldonado Carbo en el año 2015. 2016. Trabajo de grado – Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Awoke N, Tekalign T, Teshome M, Lolaso T, Dendir G, Obsa MS. Bacterial Profile and asymptomatic bacteriuria among pregnant women in Africa: a systematic review and meta analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;37:100952.

Getaneh T, Negesse A, Dessie G, Desta M, Tigabu A. Prevalence of urinary tract infection and its associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021.

Azami M, Jaafari Z, Masoumi M, Shohani M, Badfar G, Mahmudi L, et al. The etiology and prevalence of urinary tract infection and asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women in Iran: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2019;19(1):1–5.

Rouse D, Andrews W, Goldenberg R, Owen J. Screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria of pregnancy to prevent pyelonephritis: a cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analysis. Obst Gynecol. 1995;86(1):119-23. 192 185.

Wadland WC, Plante DA. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. A decision and cost analysis. J Fam Pract. 1989;29(4):372–6.

Yang X, Chen H, Zheng Y, Qu S, Wang H. Yi F. Disease burden and long-term trends of urinary tract infections: A worldwide report. Front Public Health; 2022. p. 10.

Smaill FM, Vazquez JC. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(11):CD000490.

Collin SM, Shetty N, Guy R, Nyaga VN, Bull A, Richards MJ, et al. Group B Streptococcus in surgical site and non-invasive bacterial infections worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;83:116–29.

TabNet Win32 3.0: Nascidos vivos - Brasil. Cited 2022 Jun 26. Available from: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?sinasc/cnv/nvuf.def.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the employees of the Obstetric Clinic at the Clinics Hospital of the Medical School, the University of São Paulo.

All listed authors helped write the first draft of the manuscript. No payment was made to anyone to produce the manuscript. The corresponding author would also like to state that all authors who contributed significantly to this work have been included in the list of authors.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HDS and MAKG read the abstracts, selected and read the full articles. HDS wrote the manuscript in its initial draft. MAKG contributed to the final writing of the manuscript. SVP performed the statistical analysis related to the meta-analysis. GRMD assisted in reading some articles and wrote the manuscript in its initial draft. RPVF reviewed the final article and provided general supervision of the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supp 1. Funnel plot to test the publication bias in 67 studies with 95% Confidence limits. Suppl 2. Funnel plot to test the publication bias in 10 studies with 95% Confidence limits. Supp 3. Funnel plot to test the publication bias in 5 studies with 95% Confidence limits. Supp 4. Prevalence of bacteriuria in pregnant women in Latin America, considering only articles published with samples greater than 500 individuals. Supp 5. Funnel plot to test the publication bias in 15 studies with 95% Confidence limits. Supp 6. Prevalence of bacteriuria in pregnant women in Latin America, with the exception of Brazilian articles. Supp 7. Prevalence of bacteriuria in pregnant women in Latin America, with the exception of Brazilian articles, in studies with samples greater than 200 individuals. Supp 8. Funnel plot to test the publication bias in 28 studies with 95% Confidence limits. Supp 9. Funnel plot to test the publication bias in 20 studies with 95% Confidence limits. Supp 10. Prevalence of bacteriuria in Brazilian pregnant women, considering published or unpublished studies, in studies with samples greater than 200 individuals. Supp 11 Funnel plot to test the publication bias in 10 studies with 95% Confidence limits. Supp 12. Prevalence of Escherichia coli among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. Supp 13. Prevalence of Klebsiella sp. among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. Supp 14. Prevalence of Staphilococcus sp. (exceptStaphilococcus aureus) among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. Supp 15. Prevalence of Proteus mirabilis among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. Supp 16. Prevalence of Enterobacter sp. among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. Supp 17. Prevalence of Enterococcus sp. among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. Supp 18. Prevalence of Streptococcus agalactiae among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. Supp 19. Prevalence of Staphilococcus aureus among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. Supp 20 Prevalence of Citrobacter sp. among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women. Supp 21. Prevalence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa among the total number of uropathogens isolated from urine cultures of Latin American pregnant women.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

de Souza, H.D., Diório, G.R.M., Peres, S.V. et al. Bacterial profile and prevalence of urinary tract infections in pregnant women in Latin America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 774 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-06060-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-06060-z