Abstract

Background

Women of Afro-Caribbean and Asian origin are more at risk of stillbirths. However, there are limited tools built for risk-prediction models for stillbirth within sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, we examined the predictors for stillbirth in low resource setting in Northern Uganda.

Methods

Prospective cohort study at St. Mary’s hospital Lacor in Northern Uganda. Using Yamane’s 1967 formula for calculating sample size for cohort studies using finite population size, the required sample size was 379 mothers. We doubled the number (to > 758) to cater for loss to follow up, miscarriages, and clients opting out of the study during the follow-up period. Recruited 1,285 pregnant mothers at 16–24 weeks, excluded those with lethal congenital anomalies diagnosed on ultrasound. Their history, physical findings, blood tests and uterine artery Doppler indices were taken, and the mothers were encouraged to continue with routine prenatal care until the time for delivery. While in the delivery ward, they were followed up in labour until delivery by the research team. The primary outcome was stillbirth 24 + weeks with no signs of life. Built models in RStudio. Since the data was imbalanced with low stillbirth rate, used ROSE package to over-sample stillbirths and under-sample live-births to balance the data. We cross-validated the models with the ROSE-derived data using K (10)-fold cross-validation and obtained the area under curve (AUC) with accuracy, sensitivity and specificity.

Results

The incidence of stillbirth was 2.5%. Predictors of stillbirth were history of abortion (aOR = 3.07, 95% CI 1.11—8.05, p = 0.0243), bilateral end-diastolic notch (aOR = 3.51, 95% CI 1.13—9.92, p = 0.0209), personal history of preeclampsia (aOR = 5.18, 95% CI 0.60—30.66, p = 0.0916), and haemoglobin 9.5 – 12.1 g/dL (aOR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.11—0.93, p = 0.0375). The models’ AUC was 75.0% with 68.1% accuracy, 69.1% sensitivity and 67.1% specificity.

Conclusion

Risk factors for stillbirth include history of abortion and bilateral end-diastolic notch, while haemoglobin of 9.5—12.1 g/dL is protective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stillbirth is the death of a fetus before birth after 20 weeks of gestation [1]. In the early twentieth century, stillbirth was any child who exhibits no sign of life by crying or breathing, or by pulsation in the cord at its attachment to the body of the child, or by beating of the heart and measuring more than 13 inches in length from the top of head to the heel at birth [2]. In the late twentieth century stillbirth was defined as any baby born at 24 weeks of gestation without a sign of life [3]. It can be classified as an early (24 – 27 weeks), late (28 – 36 weeks), or term ( 37 weeks) stillbirth [4].

The global prevalence of stillbirth is approximately 2% [5], with 0.3% occurring in the global north [6, 7], and more than 2% in the global south [5, 8,9,10]. Women of Afro-Caribbean and Asian origin are more at risk of stillbirths [7, 11,12,13,14] and this may be associated with racial disparities in accessing health care [12]. Incidence of stillbirth in Uganda is about 2.0%—3.6% [15, 16]. However, due to challenges in access to care and policies on death registration in the global south, most stillbirths are not registered [17].

When maternal obesity, smoking, chronic hypertension, antiphospholipid syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and insulin requirement are used in a prediction model risk calculator for stillbirth [18], it predicted stillbirths at 60—72% AUC at 75% sensitivity and close to 100% specificity [6, 7, 19]. When maternal history and fetal growth rates were added to maternal history without using the risk calculator, the discriminative performance of the model had a C-statistic of 0.80 [8].

There are limited number of tools built for risk-prediction models for stillbirth within sub-Saharan Africa. With the problems of access to hospital delivery and African ancestry being a risk factor for stillbirth, we set out to develop and validate a prediction model for stillbirth in Northern Uganda.

Materials and methods

Study design

A prospective cohort study at St. Mary’s Hospital Lacor, which is one of the teaching hospitals of Gulu University. Using Yamane’s 1967 formula for calculating sample size for cohort studies using finite population size, St. Mary’s hospital Lacor delivers approximately seven thousand mothers per year. Since my study duration was 12 months for recruitment of the mothers, the finite population I could access was about 7,000 mothers. Yamane 1967 formula:

where N is the finite population size 7,000 mothers.

Margin of error (e) 05%

Therefore n = 7,000 / 1 + 7,000(0.05).2

n = 379.

The required sample size was 379 mothers. We doubled the number (to > 758) to cater for loss to follow-up, miscarriages, and clients opting out of the study during the follow-up period. Recruited 1,285 pregnant mothers 16 – 24 weeks from April 2019 to March 2020. Excluded all with lethal congenital anomalies diagnosed on ultrasound scan especially molar pregnancy, anencephaly, and cystic hygroma. A questionnaire was filled, and uterine artery Doppler sonography was done on all the mothers. The ultrasonography was done by one trained obstetrician. A full foetal anatomical survey was done in addition to the uterine artery Doppler indices (pulsatility and resistive indices, end-diastolic notch). Blood samples were taken for complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, from one thousand (1,000) mothers. The mothers were encouraged to continue with routine antenatal care until the time for delivery. While admitted to the delivery ward, the mothers were followed up by the research team until delivery of the baby. The last mother was delivered at the end of September 2020.

Outcome

The Apgar score of zero within the first minute of birth at 24 + weeks was taken as stillbirth.

Statistical analysis

One thousand four (1,004) complete delivery records were obtained. Data were pre-processed using Stata 15.0 and built models using RStudio R version 4.1.1 (2021–08-10). Univariable analysis was done, and all variables with p-values ≤ 0.20 or were known risk factors for stillbirth like age and maternal comorbidities were put together into a logistic regression model. Since the data was imbalanced with few stillbirths, we applied the ROSE technique [20, 21] to create a new dataset by over-sampling stillbirths and under-sampling live births, and obtained a distribution of live births and stillbirth cases as 400 (51.1%) and 383 (48.9%), respectively. The ROSE-derived data set was fitted into a confusion matrix to evaluate the performance of our models (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity) using K-(10)-fold cross-validation. Variables were said to be independent risk factors of stillbirth if their p-value < 0.05 in the model. Six models were built.

Results

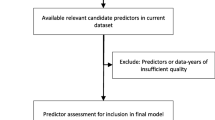

One thousand four (1004) complete delivery records were obtained at the end of the study period.. Of these, seven hundred eighty two mothers had laboratory blood tests done with 2.4% (19) stillbirths and 97.6% (763) live-births. Prevalence of stillbirth was 2.5% (25 out of 1004). There was 979 (97.5%) live births. Seven (28%) out of the 25 deaths occurred intrapartum. Two (8%) of the 25 mothers who lost their babies had a history of previous stillbirth. Two hundred eighty-one mothers were lost to follow-up. Details are found in Fig. 1.

The incidence rates for stillbirth were higher at lower gestation ages, as outlined in Table 1. There were 273 stillbirths per 104 women weeks at < 28 weeks while only 3 stillbirths per 104 women weeks at ≥ 37 weeks.

Second trimester characteristics of the women who returned to deliver in hospital

Mean maternal age was 26.3 years while 316 participants were first time mothers. Details in Table 2.

Average body-mass index (BMI) was 24.7, and prevalence of multiple pregnancy was 2.4%. Only 0.6% (6) of participants had prenatal hypertension at the time of recruitment. Details in Table 3.

Prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy was high with a mean haemoglogin level of 10.7 g/dL and haematocrit levels of 32.6%. Details in Table 4.

Unadjusted logistic regression for stillbirth with demographic characteristics

Personal history of preeclampsia and any history of abortion were significantly related to stillbirth while being married or cohabiting was protective. Details in Table 5.

While for the clinical characteristics; systolic hypertension, end diastolic notch, pulsatility and resistive indices were significantly related to stillbirth. Details in table 6.

When laboratory characteristics were used, there were no significant relationship to stillbirth. Details in Table 7.

All the variables with unadjusted p-value of ≤ 0.200 were taken for multivariable analysis to produce the models for prediction of stillbirth. Six models were built in R-studio. The variables are removed from the model in a stepwise manner to remain with the least number of variables with a high AUC. Those variables with p < 0.1 were retained in the model while those with p < 0.05 were taken as independent risk factors for stillbirth.

Models for prediction of stillbirth

Model 1 examined maternal history and physical examination (details in Table 8). The predictors of stillbirth were parity, age ≥ 35 years, history of abortion and personal history of preeclampsia. Personal history of preeclampsia (aOR = 11.08, 95% CI 1.44—57.34, p = 0.0075) and history of abortion (aOR = 2.92, 95% CI 1.07—7.57, p = 0.0293) were independent risk factors for stillbirth.

Model 2 examined the uterine artery Doppler indices (details in Table 9). The predictor of stillbirth was presence of end diastolic notch on the uterine artery Doppler flow tracing. Bilateral end diastolic notch (aOR = 4.28, 95% CI 1.54—11.19, p = 0.0035) was an independent risk factor for stillbirth.

Model 3 examined the combination of maternal history, physical examination and uterine artery Doppler indices (models 1 and 2) (details in Table 10). The predictors of stillbirth were history of abortion and end-diastolic notch on the uterine artery Doppler flow tracing. The history of abortion (aOR = 3.29, 95% CI 1.24—8.41, p = 0.0134) and bilateral end-diastolic notch (aOR = 4.49, 95% CI 1.60—11.88), p = 0.0029) were independent risk factors for stillbirth.

Model 4 examined maternal laboratory blood tests (details in Table 11). The predictors of stillbirth were platelet neutrophil ratio, neutrophil count and haemoglobin level. The independent risk factors for stillbirth was platelet neutrophil ratio of > 83.95 (aOR = 5.76, 95% CI 1.12—35.90, p = 0.0437). Haemoglobin level of 9.5 – 12.1 g/dL (aOR = 0.32, 95% CI 0.11—0.89, p = 0.0287) was protective against stillbirth.

Model 5 examined the combination of maternal history and laboratory tests (models 1 and 4) (details in Table 12). The predictors of stillbirth were history of abortion, parity, age ≥ 35 years and haemoglobin level. The independent risk factors for stillbirth was history of abortion (aOR = 3.10, 95% CI 1.11—8.26), p = 0.0254). Haemoglobin level of 9.5 – 12.1 g/dL (aOR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.109—0.95, p = 0.0411) was protective against stillbirth.

Model 6 examined the combination of maternal history, physical examination, uterine artery Doppler indices and laboratory tests (models 1, 2 and 4) (details in Table 13).The predictors of stillbirth were personal history of preeclampsia, history of abortion, end-diastolic notch and haemoglobin level. The history of abortion (aOR = 3.07, 95% CI 1.11—8.05, p = 0.0243) and bilateral end diastolic notch (aOR = 3.51, 95% CI 1.13—9.92, p = 0.0209) were independent risk factors for stillbirth while haemoglobin level of 9.5 – 12.1 g/dL (aOR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.11—0.93, p = 0.0375) was protective.

Evaluation of the models of stillbirth

The models AUC ranges from 66.8% to 75.0%, with accuracies of 63.9% to 68.1%. Details in Table 14.

Model 1 examined maternal history and physical examination (details in Table 8). The predictors of stillbirth were parity, age ≥ 35 years, history of abortion and personal history of preeclampsia. This predicted stillbirth with 65.8% accuracy, 82.4% sensitivity, 48.4% specificity and 71.9% AUC. The details for the models are found in Table 14.

Discussion

From demographic characteristics of our participants, the predictors of stillbirth were parity, age ≥ 35 years, history of abortion and personal history of preeclampsia. This predicted stillbirth with 65.8% accuracy, 82.4% sensitivity, 48.4% specificity and 71.9% AUC. In Niger state Nigeria, the predictors of stillbirth were maternal comorbidity, rural place of residence, multipara, bleeding during pregnancy, and non-cephalic fetal presentation [8]. Maternal employment was protective of stillbirth [8]. They predicted stillbirth with a C-statistic basic model = 0.80 (95% CI 0.78–0.83), and when ultrasound parameters were added the extended C-statistic model improved slightly to 0.82 (95% CI 0.80–0.83)[8]. In a case–control study in southern Ethiopia, the predictors of stillbirth were women with multiple pregnancy [aOR = 2.98, 95%CI: 1.39–6.36], having preterm birth [aOR = 2.83, 95%CI: 1.58– 508], having cesarean mode of delivery [aOR = 3.19, 95%CI: 1.87–5.44], having no ANC visit [aOR = 4.17, 95%CI: 2.38–7.33], and being hypertensive during pregnancy [aOR = 3.43, 95%CI: 1.93–6.06].[22]. However, these women were recruited after they had given birth. In clinical settings in low resource settings one can use the demographic characteristics above as predictors to identify up to two-thirds of mothers at risk of having stillbirth. Despites the model’s sensitivity of 82.4%, the model’s specificity of 48.4% is low. One will have to put more than twice the number of women identified as at risk of stillbirth in order to get the two thirds of women who will actually get stillbirth.

Combination of uterine artery Doppler indices and maternal history predicted stillbirth by 67.6% accuracy, 75.8% sensitivity and 69.9% AUC. This may be comparable to Akolekar et al.[19] who predicted 55% of all stillbirths, including 75% of those due to impaired placentation and 23% of those that were unexplained or due to other causes, at a false-positive rate of 10% using maternal history and uterine artery Doppler indices. Ultrasound examination is not compulsory in Uganda[23]. It is reserved for a few referral centers, teaching hospitals and private hospitals[24, 25]. Majority of the mothers go through their gestation period without performing a single ultrasound scan.

We predicted stillbirth by 75.0% AUC with 68.1% accuracy, 69.1% sensitivity and 67.1% specificity. This was comparable to the stillbirth-risk calculator [18] validated in Austria at 72% AUC [6]. In the United Kingdom, stillbirth detection rates ranged from 28 to 48% with an AUC of 55.0% to 65.8% even after allowing a 10% false positive rate [7, 19]. In Australia, the detection rate for stillbirth was 45%, with an AUC ranging from 59 to 84% [26]. Similarly, in the United States of America, the detection rate for stillbirth has been 64%—66% AUC [27].

Mastrodima et al. [28] used maternal factors, PAPP-A, Doppler pulsatility index and ductus venosus pulsatility index for veins (DV-PIV), and predicted 40% of all stillbirths and 55% of those due to impaired placentation, at a false-positive rate of 10%. Within the impaired-placentation group, the detection rate of stillbirth < 32 weeks’ gestation was higher than that of stillbirth ≥ 37 weeks (64% vs 42%). This makes the study compare favorably to those conducted in global north. Perhaps the differences seen is due to the differences in the population itself and the technology used for the prediction of stillbirth.

Research implications

These models may be used in several clinics. Future studies may include a larger number of participants from several locations to validate the models to ensure generalizability.

Strengths and limitation

This study was a baseline study in Northern Uganda to find out the predictors of stillbirths and to pave way for more research. There was a high number of mothers lost to follow-up.

Conclusion

In places where ultrasound or laboratory services are not available, the predictors of stillbirths are history of abortion, personal history of preeclampsia, maternal age ≥ 35 years and parity. These variables predict stillbirth by 71.9% AUC with 68.5% accuracy, 82.4% sensitivity and 48.4% specificity.

Availability of data and materials

The corresponding author Dr. Silvia Awor or Makerere University Directorate of Research and Graduate training can be contacted to request for the data and other materials.

References

WHO: International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems ICD10. In: ICD10. vol. 10, 5TH edn. online: WHO; 2010.

Definition of Stillbirth. Proc R Soc Med 1913, 6(Obstet Gynaecol Sect):64.

Cartlidge PH, Stewart JH. Effect of changing the stillbirth definition on evaluation of perinatal mortality rates. Lancet. 1995;346(8973):486–8.

Robert K. Creasy, Robert Resnik, Jay D. Iams, Charles J. Lookwood, Thomas R. Moore, Greene MF: Creasy and Resnik's maternal-fetal medicine, Principles and practice, 7th edn: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, Say L, Chou D, Mathers C, Hogan D, Shiekh S, Qureshi ZU, You D, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(2):e98–108.

Muin DA, Windsperger K, Attia N, Kiss H. Predicting singleton antepartum stillbirth by the demographic Fetal Medicine Foundation Risk Calculator—A retrospective case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0260964.

Yerlikaya G, Akolekar R, McPherson K, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides KH. Prediction of stillbirth from maternal demographic and pregnancy characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(5):607–12.

Kayode GA, Grobbee DE, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Adeleke IT, Ansah E, de Groot JA, Klipstein-Grobusch K. Predicting stillbirth in a low resource setting. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:274.

Okunowo AA, Smith-Okonu ST. The trend and characteristics of stillbirth delivery in a university teaching hospital in Lagos. Nigeria Ann Afr Med. 2020;19(4):221–9.

Bedwell C, Blaikie K, Actis Danna V, Sutton C, Laisser R, Tembo Kasengele C, Wakasiaka S, Victor S, Lavender T. Understanding the complexities of unexplained stillbirth in sub-Saharan Africa: a mixed-methods study. BJOG. 2021;128(7):1206–14.

Rowland Hogue CJ, Silver RM. Racial and ethnic disparities in United States: stillbirth rates: trends, risk factors, and research needs. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35(4):221–33.

Williams AD, Wallace M, Nobles C, Mendola P. Racial residential segregation and racial disparities in stillbirth in the United States. Health Place. 2018;51:208–16.

Willinger M, Ko CW, Reddy UM. Racial disparities in stillbirth risk across gestation in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(5):469-e461 468.

Salihu HM, Kinniburgh BA, Aliyu MH, Kirby RS, Alexander GR. Racial disparity in stillbirth among singleton, twin, and triplet gestations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):734–40.

Tesfalul MA, Natureeba P, Day N, Thomas O, Gaw SL. Identifying risk factors for perinatal death at Tororo District Hospital, Uganda: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2727-3.

Arach AAO, Tumwine JK, Nakasujja N, Ndeezi G, Kiguli J, Mukunya D, Odongkara B, Achora V, Tongun JB, Musaba MW, et al. Perinatal death in Northern Uganda: incidence and risk factors in a community-based prospective cohort study. Glob Health Action. 2021;14(1):1859823.

Kasasa S, Natukwatsa D, Galiwango E, Nareeba T, Gyezaho C, Fisker AB, Mengistu MY, Dzabeng F, Haider MM, Yargawa J, et al. Birth, stillbirth and death registration data completeness, quality and utility in population-based surveys: EN-INDEPTH study. Popul Health Metr. 2021;19(Suppl 1):14.

Risk for stillbirth calculator [https://fetalmedicine.org/research/assess/stillbirth]

Akolekar R, Tokunaka M, Ortega N, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides KH. Prediction of stillbirth from maternal factors, fetal biometry and uterine artery Doppler at 19–24 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(5):624–30.

Lunardon N, Menardi G, Nicola Torelli. ROSE: A Package for Binary Imbalanced Learning. R Journal 2014;6:1:79–89. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2014/RJ-2014-008/index.html.

Menardi G, Torelli N. Training and assessing classification rules with imbalanced data. Data Min Knowl Disc. 2014;28(1):92–122.

Abebe H, Shitu S, Workye H, Mose A. Predictors of stillbirth among women who had given birth in Southern Ethiopia, 2020: A case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0249865.

MoH U. Uganda Clinical guidelines. December. Kampala: Ministry of Health; 2016.

Ross AB, DeStigter KK, Rielly M, Souza S, Morey GE, Nelson M, Silfen EZ, Garra B, Matovu A, Kawooya MG. A low-cost ultrasound program leads to increased antenatal clinic visits and attended deliveries at a health care clinic in rural Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e78450.

Kawooya MG. Training for rural radiology and imaging in sub-saharan Africa: addressing the mismatch between services and population. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2012;2:37.

Malacova E, Tippaya S, Bailey HD, Chai K, Farrant BM, Gebremedhin AT, Leonard H, Marinovich ML, Nassar N, Phatak A, et al. Stillbirth risk prediction using machine learning for a large cohort of births from Western Australia, 1980–2015. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5354.

Trudell AS, Tuuli MG, Colditz GA, Macones GA, Odibo AO. A stillbirth calculator: Development and internal validation of a clinical prediction model to quantify stillbirth risk. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0173461.

Mastrodima S, Akolekar R, Yerlikaya G, Tzelepis T, Nicolaides KH. Prediction of stillbirth from biochemical and biophysical markers at 11–13 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(5):613–7.

DECLARATION OF HELSINKI: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects [https://www.wma.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/DoH-Oct2008.pdf]

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Ronald Kivumbi and Mr. Ronald Waiswa, the biostatisticians, for helping me with part of the preprocessing of the data for analysis. In a special way, I thank my mentor, Prof. Letseka Moeketsi, for guiding me to aim higher. The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided for writing this paper from the British Academy Writing Workshop Programme 2022, ‘Addressing Epistemic Injustice: Supporting Writing about Inclusive and Life-long Education in Africa’.

Funding

The research was carried out a PhD project funded by the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) under the Makerere University – SIDA bilateral agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Silvia Awor is a Ph.D. student who wrote the proposal, collected data and drafted the manuscript. Annettee Nakimuli, Jaspar Ogwal-Okeng and Dan Kabonge Kaye are doctoral supervisors who guided the writing of the manuscript. Rosemary Byanyima, Paul Kiondo and Christopher Garimoi-Orach are doctoral committee members who gave technical advice during the data collection and manuscript writing. Benard Abola, a mathematician, helped develop and validate the model and participated in data analysis. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Makerere University School of Medicine (Reference number 2018–105), Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (Reference number HS258ES), and administrative clearance from St. Mary’s hospital Lacor (Reference number LHIREC Adm 009/11/18). Written informed consent was sought from every participant. All methods were carried out according to the “Declaration of Helsinki” guidelines [29].

Consent for publication

Not application.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Awor, S., Byanyima, R., Abola, B. et al. Prediction of stillbirth low resource setting in Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 855 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05198-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05198-6