Abstract

Background

Pregnancy is a period of transition with important physical and emotional changes. Even in uncomplicated pregnancies, these changes can affect the quality of life (QOL) of pregnant women, affecting both maternal and infant health. The objectives of this study were to describe the quality of life during uncomplicated pregnancy and to assess its associated socio-demographic, physical and psychological factors in developed countries.

Methods

A systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines. Searches were made in PubMed, EMBASE and BDSP (Public Health Database). Two independent reviewers extracted the data. Countries with a human development index over 0.7 were selected. The quality of the articles was evaluated on the basis of the STROBE criteria.

Results

In total, thirty-seven articles were included. While the physical component of QOL decreased throughout pregnancy, the mental component was stable and even showed an improvement during pregnancy. Main factors associated with better QOL were mean maternal age, primiparity, early gestational age, the absence of social and economic problems, having family and friends, doing physical exercise, feeling happiness at being pregnant and being optimistic. Main factors associated with poorer QOL were medically assisted reproduction, complications before or during pregnancy, obesity, nausea and vomiting, epigastralgia, back pain, smoking during the months prior to conception, a history of alcohol dependence, sleep difficulties, stress, anxiety, depression during pregnancy and sexual or domestic violence.

Conclusions

Health-related quality of life refers to the subjective assessment of patients regarding the physical, mental and social dimensions of well-being. Improving the quality of life of pregnant women requires better identification of their difficulties and guidance which offers assistance whenever possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health Organization, quality of life (QOL) is defined as “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. This is a very broad concept, and one that can be influenced in a complex way by the physical health of the subject, his or her psychological state and level of independence, social relations and relationship with the essential elements of his or her environment” [1]. It is therefore founded on several objective factors (linked to the quality of the environment and living conditions), and subjective factors (linked to the personal sphere and measurable in terms of satisfaction and well-being). Health status as an essential component of quality of life is referred to as health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [2].

Pregnancy is a period of transition with important physical and emotional changes [3]. Even in uncomplicated pregnancies, these changes can affect the quality of life of pregnant women and affect both maternal and infant health (pregnancy monitoring, pregnancy outcomes, maternal postpartum health, and the psychomotor development of the infant) [4,5,6,7,8]. Health professionals in the field of prenatal maternal and child health try to satisfy their patients with respect to their experience during preconception and pregnancy periods [2]. Traditionally used pregnancy outcome measures, such as morbidity and mortality rates, remain essential. However, they are not sufficient on their own because population health should be assessed, not only on the basis of saving lives, but also in terms of improving quality of life [2, 9].

Over the past decades, numerous instruments have been developed to measure HRQOL in various patient populations, with 2 basic approaches: generic and disease-specific [10]. While generic measures (for example the SF-36 Short-Form Item 36 and WHOQOL-BREF World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Scale) have broad application across different types and severity of diseases, disease-specific measures are designed to assess particular diseases or patient populations. To our knowledge, there is no review of the literature to describe the quality of life of pregnant women in primary care. The objectives of this study were to describe the quality of life during uncomplicated pregnancy and to assess its associated socio-demographic, physical and psychological factors in developed countries.

Methods

Type of study

The study consisted of a systematic review of the literature in the PUBMED, EMBASE and BDSP databases (BDSP is the French Public Health Database). The search was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria were developed by the whole group of authors after which two authors (LN and IG) individually conducted the literature search. Key search terms included “Pregnancy”, “Quality of life”, or “Health related quality of life”. Search terms were selected with reference to relevant index terms (MeSH, Emtree or Thesaurus). All observational studies (e.g., cohort, cross-sectional, case-control) which were published in English and French prior to March 2016 have been considered (no restriction in the starting date). Developed countries were chosen as a basis for the research to ensure epidemiological uniformity. In order to define a list of developed countries comparable to France, countries with a human development index (HDI) of over 0.7 were selected. This list, provided by the United Nations (UN), is available online [11]. Studies measuring quality of life with a single question were excluded [12, 13]. Studies on specific populations (women with complicated pregnancy) or on a specific scale of quality of life (sexual HRQOL or HRQOL in relation to faecal incontinence, etc.) were also excluded, as it is not possible to compare patients with different pathologies.

HRQOL measurement

The most frequently used HRQOL instruments during pregnancy are the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 survey (SF-36), the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 12 survey (SF-12), the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Scale (WHOQOL) and the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Scale – BREF (WHOQOL – Bref).

The SF-36 includes 36 items and collects information on eight health concepts including, physical functioning, role limitations due to physical and emotional health, mental health, bodily pain, general health, vitality and social functioning. These items are scored providing a component summary scale score for both mental (SF36-MCS) and physical (SF36-PCS) HRQOL (from 0 to 100) [14]. The SF-12 is a validated shortened version of the SF-36. A lower score on the summary scales represents a poorer HRQOL.

The WHOQOL includes 100 questions grouped into 6 categories (physical, psychological, independence, social, environmental and spiritual) (from 0 to 100). The WHOQOL-BREF instrument comprises 26 items and is a validated shortened version of the WHOQOL. A lower score on the summary scales represents a poorer HRQOL.

Article selection and quality assessment

A preliminary selection was made from the titles, then another on reading the summaries and a lastly on a reading of the entire article. Publications “related” to the selected articles as well as the bibliography of the selected articles were also examined. Two independent reviewers extracted the data (LN and IG). Disagreement between reviewers was resolved by consensus. The quality of the articles was evaluated using the STROBE criteria (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) [15].

Analysis

The results were organised in two sections: first, a description of the quality of life of pregnant women in developed countries and second, by the socio-demographic, physical and psychological factors associated with their quality of life. When the study compared two quality of life scales, we used only the “Gold Standard” scale. In the case-control studies where the controls were a particular subgroup, we have retained the “control” group that was most representative of the general population of pregnant women, where all subjects in the study would have resulted in a serious selection bias.

Results

Article selection

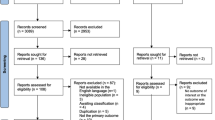

The article selection is described in Fig. 1. Of the 1487 articles retrieved, 37 were selected for our analysis (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The methodological quality was rated from 11 to 22 in the selected articles. The selected articles were published between 2001 and 2016. The samples of pregnant women included in the studies varied between 55 and 12,056 women. Concerning the design of the selected studies, twenty were cross-sectional studies [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], four were case-controlled studies [36,37,38], and fourteen were longitudinal cohort studies [14, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. Thirteen studies were conducted during the first trimester of pregnancy [17, 20, 22, 23, 26, 30, 38,39,40, 44,45,46,47], eleven were from the second trimester [14, 16, 24, 35, 38,39,40,41, 45, 46, 48], eighteen were from the 3rd trimester [14, 18, 19, 27, 29, 31, 33, 34, 37,38,39,40,41,42, 46, 48,49,50] and six studies focused on the entire pregnancy [25, 28, 32, 36, 43, 51]. In measuring the quality of life, nineteen studies used SF-36 [14, 17,18,19, 21, 22, 25,26,27, 30, 33, 34, 38,39,40,41, 44, 46, 51], twelve studies used SF-12 [16, 20, 23, 24, 28, 29, 35, 42, 43, 46, 48, 50], two studies used the WHOQOL Brief [32, 47], one study used The Duke Health Profile [49], and another Nottingham Health Profile [31].

The quality of life of pregnant women

Comparison with the general population

The quality of life of pregnant women was generally lower than that of the general population. Two studies explicitly compared their results with those of non-pregnant women of the same age. On the SF-36 scale, Da Costa et al. found physical activity and physical pain values equal to 56.7 and 61.7; these values were 90.9 and 75.0 for non-pregnant Canadian women of the same age [18]. Similarly, Nakamura et al. made similar comparisons in Japan [38]. The Chan et al. study in 2010 also found that pregnant women had, on average, statistically lower QOL scores (p < 0.001) compared to the general population, excepting general health (p = 0.1) [17, 18]. Similarly, Elsenbruch et al. [20] found a reduced quality of life, physically, when compared to German women of the same age (p < 0.001).

The progression of the quality of life during the trimesters

Of the 23 studies selected, 20 (86,9%) described the progression of QOL using SF-36 or SF-12 (Figs. 2, 3). The study of the SF-36 PCS and MCS aggregate scores revealed that there were significant variations during the trimesters (Fig. 2).

The PCS values ranged from 48 to 61 during the 1st trimester; between 39 and 55 during the 2nd trimester; between 37.5, and 47.5 during the 3rd trimester. For SF-12, values ranged from 44 to 46 in the 1st trimester, 43 and 50 in the 2nd trimester and 41 and 45 in the 3rd trimester. The results of the studies indicated a decrease in physical quality of life throughout pregnancy, particularly related to decreased physical activity and functional limitations (related to physical health and physical pain). In terms of prevalence, the Haas et al. study in 2005 showed an increase in pregnant women with poor physical quality of life during pregnancy: 9% of pregnant women in the second trimester, and 13% in the third trimester [14]. The proportion of pregnant women reporting generally poor health (score 0 to 50) increased from 15.5 to 20.1 and 26.9% and then decreased to 21% in the postpartum period [49].

The MCS values were as follows for the SF-36: in the 1st trimester values between a minimum of 51 and a maximum of 58; in the 2nd trimester between 49 and 62; in the 3rd trimester between 49.5 and 66. In parallel with SF-12, the MCS was between 47 and 48 in the first trimester, between 49 and 52 in the second trimester and 50 and 54 in the third trimester. In five studies, the quality of mental life of the pregnant women increased or remained stable over the course of the trimesters (Fig. 2).

The evolution of the 8 dimensions of SF-36 during the quarters is presented in Fig. 3. The following domains had the lowest scores: role limitations due to physical problems (RP) and vitality (VT). The following domains had the highest scores: general health perceptions (GH) and bodily pain (BP). The results concerning the role limitations due to emotional problems (RE) varied across studies.

Factors influencing quality of life

The results of studies on the factors associated with the quality of life of pregnant women are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Thirty-three articles were selected for this section.

Socio-demographic factors

The following socio-demographic factors were strongly associated with a better quality of life in 15 studies: mean maternal age, primiparity, early gestational age, the absence of economic problems, a high educational level, being employed, being married, having family and friends. With less consensus, belonging to an ethnic minority and alcohol consumption have also been associated in 2 studies with a poorer quality of life.

Physical factors

Medically assisted reproduction, obstetric complications, medical history, possible hospitalisation and obesity were factors frequently indicating a poor quality of life during pregnancy (in 9 studies). Physical symptoms associated with pregnancy such as nausea and vomiting, epigastralgia, reflux, shortness of breath, dizziness, back pain and sleep problems affected women’s quality of life. Exercise was a factor that improved the quality of life of pregnant women. With less consensus, we found other factors associated with a poorer QOL such as smoking during the months prior to conception, a history of alcohol dependence and poor comfort.

Psychological factors

Eight studies have shown that symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress were factors that had a strong negative impact on the quality of life of pregnant women. Sexual and domestic violence was linked to a lower quality of life, as well as the experience of life-threatening events and the experience of infertility. Happiness at being pregnant and being optimistic were factors related to a better quality of life.

Discussion

Summary of results

Pregnant women, especially during the third trimester, had significantly lower quality of life scores than non-pregnant women of the same age. Physically, the quality of life decreased significantly during the course of the trimesters. On a psychological level, several studies reported an increase in quality of life relative to mental health during pregnancy, and in others psychological stability was seen. Many factors were associated with the quality of life in pregnant women. Some factors associated with higher well-being were socio-demographic (first-time pregnancy, a favourable socio-economic status, social support, partner support). Similarly, the desire to be pregnant and moderate physical activity were factors associated with a positive quality of life. A lesser quality of life was attributed to physical factors, (such as complications during pregnancy, medically assisted reproduction, obesity prior to conception, physical symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, sleep difficulties), and otherwise attributed to psychological factors, (such as anxiety and stress during pregnancy and depressive symptoms).

Strengths and limitations of the study

To our knowledge, this is the only systematic review of international literature aimed at synthesizing data regarding the quality of life of pregnant women. Many factors have been studied, considering the different dimensions of the quality of life, for pregnant women in general good health. This work also has its limitations: the research only included articles written in English or French. Therefore, the issue of generalizability should be discussed. In addition, two other articles could not be read in their entirety. Within the selected studies, few studies were multi-centric and only one study used information from a large national survey. In addition, we found a high degree of heterogeneity in the methodology for population selection, in choosing the quality of life scale, as well as in the results presented (dimensions of SF-36, composite scores, etc) complicating the synthesis study. Specific HRQOL questionnaires were not included because they are focused more on specific problems in pregnancy (such as nausea and vomiting) rather than on women’s overall well-being and their quality of life. With regard to the quality of these studies, three studies did not explicitly take into account the confounding factors in the presentation of the results [22, 38, 47], which may lead to confusion bias. In addition, a large number of studies were cross-sectional. These studies did not establish an associative cause-and-effect relationship.

Research and policy implications

In some countries, the quality of life of pregnant woman has been little studied. In France, for example, only one study provided information on pregnant women well-being [6] (study not included in our analysis – cf. exclusion criteria). In this study, the mental health of pregnant women was measured through the following question: “On a psychological level, how did you feel during your pregnancy? Well, Quite well, Quite poor, Poor”. Of the 14,326 women interviewed, 8.9% reported poor self-rated mental health during pregnancy. Moreover, sociodemographic characteristics indicative of social disadvantage were associated with a higher-risk of poor quality of life; sometimes, a social gradient was observed. [6, 52]. Since SF-36 is a generic scale, it allows comparisons with chronic pathologies such as diabetes. The results obtained concerning physical activity and pain in pregnant women can be compared to those obtained for chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer [18]. A study by Sprangers et al. in 2000 found an average value of 58 in the “Physical Functions” and 64 in the “Bodily Pain” categories concerning diabetic patients [53]. In comparison, we found values between 53 and 77 for “Physical Functions” and between 48 and 74 for “Bodily Pain” in pregnant women. Moreover, quality of life refers to subjective elements that may vary from one culture to another. In the Coban et al. study undertaken in three countries over three continents: China, Ghana, USA [25], the subjective concepts of “well-being” or “vitality” were perceived and measured in very different ways on the three continents. This study did not focus on the quality of life of fathers. According to the Abassi et al. study, the quality of life of fathers was significantly higher during pregnancy and postpartum than that of their partner [39]. Specifically, their physical quality of life was significantly higher. Their mental quality of life was close, and there was no significant difference between them and their partner in two studies where this was studied [41, 43]. Finally, we believe that it is necessary to systematically screen women having a poor quality of life during pregnancy. Studies have to determine whether a single question is sufficient in clinical practice or whether it is preferable to have a more specific questionnaire before the follow-up consultation.

Conclusions

Health-related quality of life refers to the subjective assessment of patients regarding the physical, mental and social dimensions of well-being. Women’s subjective perception of their health-related quality of life is an essential measure of the quality and effectiveness of maternal and child health interventions. However, few women (less than 20%) speak spontaneously about their psychological ill-health to a health professional. Health authorities’ recommendations are needed to better detect a poor quality of life of pregnant women and to evaluate the impact of care in terms of quality of life of pregnant women. Then, given the diversity of factors associated with the quality of life, the medical and paramedical professions need to work in cohesion with social agencies, networks, and associations.

References

Programme on Mental Health, Worl Health Organization. WHOQOL Measuring Quality of Life. 1997 [cited 2017 May 23]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/68.pdf

Mogos MF, August EM, Salinas-Miranda AA, Sultan DH, Salihu HMA. Systematic review of quality of life measures in pregnant and postpartum mothers. Appl Res Qual Life. 2013;8:219–50.

Bourgoin E, Callahan S, Séjourné N, Denis A. Image du corps et grossesse : vécu subjectif de 12 femmes selon une approche mixte et exploratoire. Psychol Fr. 2012;57:205–13.

Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Larouche J, Brender W. Psychosocial predictors of labor/delivery complications and infant birth weight: a prospective multivariate study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;21:137–48.

Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Cullen C, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Prepartum, postpartum, and chronic depression effects on newborns. Psychiatry. 2004;67:63–80.

Ibanez G, Blondel B, Prunet C, Kaminski M, Saurel-Cubizolles M-J. Prevalence and characteristics of women reporting poor mental health during pregnancy: findings from the 2010 French National Perinatal Survey. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2015;63:85–95.

Graignic-Philippe R, Tordjman S. Effets du stress pendant la grossesse sur le développement du bébé et de l’enfant. Arch Pédiatrie. 2009;16:1355–63.

Chang S-R, Kenney NJ, Chao Y-MY. Transformation in self-identity amongst Taiwanese women in late pregnancy: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:60–6.

World Bank. World Dev Report 1993: Investing in Health. New York: Oxford University Press. © World Bank; 1993. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5976

Wells GA, Russell AS, Haraoui B, Bissonnette R, Ware CF. Validity of quality of life measurement tools—from generic to disease-specific. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2011;88:2–6.

Rapport sur le développement humain. Pérenniser le progrès humain: réduire les vulnérabilités et renforcer la résilience. New York: Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement; 2014. p. 2014.

Debout C. Le concept de qualité de vie en santé, une définition complexe. Soins. 2011;56:32-4.

Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–9.

Haas JS, Jackson RA, Fuentes-Afflick E, Stewart AL, Dean ML, Brawarsky P, et al. Changes in the health status of women during and after pregnancy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:45–51.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies | The EQUATOR Network. [cited 2017 Oct 8]. Available from: http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/

de Aquino NMR, Sun SY, de Oliveiraw EM, Martins MG, da Silva JF, Mattar R. Sexual violence and its association with health self-perception among pregnant women. Rev Saude Publ. 2009;43:954–60.

Chan OK, Sahota DS, Leung TY, Chan LW, Fung TY, Lau TK. Nausea and vomiting in health-related quality of life among Chinese pregnant women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:512–8.

Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Verreault N, Balaa C, Kudzman J, Khalifé S. Sleep problems and depressed mood negatively impact health-related quality of life during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13:249–57.

Dall’alba V, Callegari-Jacques SM, Krahe C, Bruch JP, Alves BC, de Barros SGS. Health-related quality of life of pregnant women with heartburn and regurgitation. Arq Gastroenterol. 2015;52:100–4.

Elsenbruch S. Social support during pregnancy: effects on maternal depressive symptoms, smoking and pregnancy outcome. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):869–77.

Gharacheh M, Azadi S, Mohammadi N, Montazeri S, Khalajinia Z. Domestic violence during pregnancy and Women’s health-related quality of life. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015;8(2):27–34.

Jomeen J, Martin CR. The factor structure of the SF-36 in early pregnancy. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59:131–8.

Lacasse A, Rey E, Ferreira E, Morin C, Bérard A. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: what about quality of life? BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;115:1484–93.

Lau Y, Yin L. Maternal, obstetric variables, perceived stress and health-related quality of life among pregnant women in Macao, China. Midwifery. 2011;27:668–73.

Li J, Mao J, Du Y, Morris JL, Gong G, Xiong X. Health-related quality of life among pregnant women with and without depression in Hubei, China. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1355–63.

Liu L, Setse R, Grogan R, Powe NR, Nicholson WK. The effect of depression symptoms and social support on black-white differences in health-related quality of life in early pregnancy: the health status in pregnancy (HIP) study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:125.

Mckee MD, Cunningham M, Jankowski KR, Zayas L. Health-related functional status in pregnancy: relationship to depression and social support in a multi-ethnic population. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):988–93.

Mota N, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Calhoun L, Sareen J. The relationship between mental disorders, quality of life, and pregnancy: findings from a nationally representative sample. J Affect Disord. 2008;109:300–4.

Moyer CA, Yang H, Kwawukume Y, Gupta A, Zhu Y, Koranteng I, et al. Optimism/pessimism and health-related quality of life during pregnancy across three continents: a matched cohort study in China, Ghana, and the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:39.

Nicholson WK, Setse R, Hill-Briggs F, Cooper LA, Strobino D, Powe NR. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:798–806.

Olsson C, Nilsson-Wikmar L. Health-related quality of life and physical ability among pregnant women with and without back pain in late pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:351–7.

Shishehgar S, Dolatian M, Majd HA, Bakhtiary M. Perceived pregnancy stress and quality of life amongst Iranian women. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6:270–7.

Fatemeh A, Azam B, Nahid M. Quality of life in pregnant women results of a study from Kashan, Iran. Pak J Med Sci. 2010;26(3):692–7.

Tavoli Z, Tavoli A, Amirpour R, Hosseini R, Montazeri A. Quality of life in women who were exposed to domestic violence during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:19.

Ramírez-Vélez R. Pregnancy and health-related quality of life: a cross sectional study. Colomb Med. 2011;42(4):476–81.

Gezginc K, Uguz F, Karatayli S, Zeytinci E. The impact of obsessive-compulsive disorder in pregnancy on quality of life. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2008;12:134–7.

Coban A, Arslan GG, Colakfakioglu A, Sirlan A. Impact on quality of life and physical ability of pregnancy-related back pain in the third trimester of pregnancy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(11):1122–4.

Nakamura Y, Takeishi Y, Atogami F, Yoshizawa T. Assessment of quality of life in pregnant Japanese women: comparison of hospitalized, outpatient, and non-pregnant women. Nurs Health Sci. 2012;14:182–8.

Abbasi M, Van den Akker O, Bewley C. Persian couples’ experiences of depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life in the pre- and perinatal period. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;35:16–21.

Chang S-R, Chen K-H, Lin M-I, Lin H-H, Huang L-H. Lin W-A. a repeated measures study of changes in health-related quality of life during pregnancy and the relationship with obstetric factors. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:2245–56.

De Pascalis L, Agostini F, Monti F, Paterlini M, Fagandini P, La Sala GB. A comparison of quality of life following spontaneous conception and assisted reproduction. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet 2012;118:216–219.

Emmanuel EN, Sun J. Health related quality of life across the perinatal period among Australian women. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:1611–9.

Ngai F-W, Ngu S-F. Quality of life during the transition to parenthood in Hong Kong: a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;34:157–62.

Setse R, Grogan R, Pham L, Cooper LA, Strobino D, Powe NR, et al. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life during pregnancy and after delivery: the health status in pregnancy (HIP) study. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:577–87.

Tendais I, Figueiredo B, Mota J, Conde A. Physical activity, health-related quality of life and depression during pregnancy. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27:219–28.

Tsai S-Y, Lee P-L, Lin J-W, Lee C-N. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between sleep and health-related quality of life in pregnant women: a prospective observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;56:45–53.

Vachkova E, Jezek S, Mares J, Moravcova M. The evaluation of the psychometric properties of a specific quality of life questionnaire for physiological pregnancy. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:214.

Vinturache A, Stephenson N, McDonald S, Wu M, Bayrampour H, Tough S. Health-related quality of life in pregnancy and postpartum among women with assisted conception in Canada. Fertil Steril 2015;104:188–195.e1.

Wang P, Liou S-R, Cheng C-Y. Prediction of maternal quality of life on preterm birth and low birthweight: a longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:124.

Emmanuel E, St John W, Sun J. Relationship between social support and quality of life in childbearing women during the perinatal period. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41:E62–70.

Hama K, Takamura N, Honda S, Abe Y, Yagura C, Miyamura T, et al. Evaluation of quality of life in Japanese Normal pregnant women. Acta Med Nagasakiensa. 2007;52(4):95–9.

Ibanez G. Santé mentale des femmes enceintes et développement de l’enfant. Thèse de doctorat en santé publique. Paris. Thèse de doctorat en santé publique; 2014.

Sprangers MA, de Regt EB, Andries F, van Agt HM, Bijl RV, de Boer JB, et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:895–907.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: NL, GI. Collection and assembly of data: NL, NG, MS, SR, GI. Data analysis and interpretation: NL, NG, MS, SR, GI, AK, JC. Coordination of the research project, conception and interpretation of data: AMM. Substantial contributions to the first draft of the article: NL, NG, MS, SR, GI, AMM, AK, JC. Work on the revised version of the manuscript: MS and NG. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

None of the authors have any competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lagadec, N., Steinecker, M., Kapassi, A. et al. Factors influencing the quality of life of pregnant women: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 455 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2087-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2087-4