Abstract

Background

Complex interactions between the immune system and the brain may affect neural development, survival, and function, with etiological and therapeutic implications for neurodegenerative diseases. However, previous studies investigating the association between immune inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have yielded inconsistent results.

Methods

We applied Mendelian randomization (MR) to examine the causal relationship between immune cell traits and AD risk using genetic variants as instrumental variables. MR is an epidemiological study design based on genetic information that reduces the effects of confounding and reverse causation. We analyzed the causal associations between 731 immune cell traits and AD risk based on publicly available genetic data.

Results

We observed that 5 immune cell traits conferred protection against AD, while 7 immune cell traits increased the risk of AD. These immune cell traits mainly involved T cell regulation, monocyte activation and B cell differentiation. Our findings suggest that immune regulation may influence the development of AD and provide new insights into potential targets for AD prevention and treatment. We also conducted various sensitivity analyses to test the validity and robustness of our results, which revealed no evidence of pleiotropy or heterogeneity.

Conclusion

Our research shows that immune regulation is important for AD and provides new information on potential targets for AD prevention and treatment. However, this study has limitations, including the possibility of reverse causality, lack of validation in independent cohorts, and potential confounding by population stratification. Further research is needed to validate and amplify these results and to elucidate the potential mechanisms of the immune cell-AD association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive impairment of memory, cognition, and behavior, resulting in severe deterioration of patients’ quality of life and social function [1, 2]. Globally, approximately 50 million people are affected by AD or other forms of dementia [3]. The current pharmacological interventions employed for AD, namely cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA receptor antagonists, primarily offer symptomatic relief without exerting any substantial influence on the underlying pathological processes of neuronal degeneration and demise. These treatments are incapable of modifying or reversing the progressive neurodegenerative cascade associated with the disease [4, 5]. Hence, it is crucial to identify modifiable risk factors and preventive strategies for AD.

Early-life exposure to various stimuli, such as infections, trauma, stress, and others, can trigger peripheral immune responses that are associated with neurodegeneration in later life, as evidenced by several epidemiological studies [6,7,8]. The intricate interplay between the immune system and the brain, which affects neural development, survival, and function, may have etiological and therapeutic implications for neurological disorders such as AD. Cytokines, which are essential mediators of infection and inflammation, participate in the bidirectional communication between the brain and the immune system [9]. Patients with AD exhibit altered levels of various cytokines in their blood and cerebrospinal fluid, indicating a chronic low-grade systemic inflammation. Moreover, different immune cells, such as macrophages, microglia, T lymphocytes, and B lymphocytes, play a role in the pathogenesis of AD [10,11,12]. These cells modulate amyloid-β (Aβ) clearance, neuronal viability, synaptic plasticity, and other mechanisms [13].

Recent studies have revealed that immune regulation influences the development of AD through multiple pathways, such as epigenetic modifications, checkpoint molecules, neurotrophic factors, and adrenergic signaling [14,15,16,17,18]. Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and noncoding RNAs, regulate the expression of genes involved in immune responses and neurodegeneration [19, 20]. Checkpoint molecules, such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), are involved in regulating immune responses and preventing excessive immune activation [21]. Neurotrophic factors, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), are secreted by immune cells and affect neuronal survival, differentiation, and function [22]. Adrenergic signaling, mediated by the sympathetic nervous system and catecholamines, modulates the activity and phenotype of immune cells and influences the inflammatory milieu in the brain [23]. These studies suggest that immune regulation is a key factor in the pathophysiology of AD and a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

However, the relationship between immune cells and AD has been inconclusive across previous studies, potentially due to methodological challenges such as small sample sizes, inadequate experimental design, and confounding variables [24, 25].

Mendelian randomization (MR) is an analytical technique based on the principles of Mendelian genetics, mainly used for causal inference in epidemiology. It utilizes genetic variation as an instrumental variable (IV) for risk factors. To ensure valid IVs for causal inference, three core assumptions must be satisfied: (1) a direct association between genetic variation and exposure, (2) no association between genetic variation and potential confounders between exposure and outcome, and (3) no influence of genetic variation on outcomes through pathways other than exposure [26,27,28,29]. Previous observational studies have identified numerous immune cell characteristics associated with AD [30,31,32,33]. In this study, we performed a comprehensive two-sample MR analysis to examine the causal relationship between 731 immune cell characteristics and AD.

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the causal relationship between immune cell variations and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease using Mendelian randomization analysis. We aim to overcome the limitations of previous observational studies by leveraging genetic variation as an instrumental variable, thereby providing more robust evidence for the role of immune cells in the pathogenesis of AD.

Materials and methods

Study design

Mendelian randomization (MR) is an analytical method that uses genetic variants, known as instrumental variables (IVs), to establish causal relationships between an exposure (risk factor) and an outcome. This method relies on three key assumptions: (a) the chosen genetic variants (or single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) are associated with the exposure, (b) they are not associated with confounders, and (c) they influence the outcome only through the exposure, not through other pathways [34].

Data sources and selection of instrumental variables

We used summary statistics from a genome-wide association study (GWAS) for AD from the FinnGen project (R9), which involved 9301 cases and 367,976 controls of European ancestry. We also sourced summary statistics of immune-related GWAS from the GWAS Catalog (accession numbers GCST90001391 to GCST90002121) [35]. Both datasets were of European populations, ensuring consistency in our analysis.

For the selection of instrumental variables, we first chose SNPs at a genome-wide significance threshold of P < 1 × 10− 5. Next, we ensured independence of the instruments by applying a linkage disequilibrium clumping procedure with a stringent cut-off r2 = 0.001 and distance = 10,000 kb. Lastly, we only retained SNPs that were more strongly associated with the exposure than the outcome (Pexposure < Poutcome), to avoid direct associations with the outcome.

Statistical analyses

We applied multiple MR methods, including inverse-variance weighted (IVW), weighted mode, sample mode, weighted median, and MR Egger. Each of these methods has specific strengths, and together they provide a comprehensive analysis:(1). IVW: This is the primary method, which uses all the genetic variants to estimate the causal effect. (2). Weighted mode: Gives more weight to the most frequently observed causal estimate, useful when a subset of instruments is valid. (3). Sample mode: Uses a simple count rather than weighting, providing a robust estimate when a mode exists. (4). Weighted median: Balances precision with robustness to invalid IVs, providing a valid causal estimate even if up to 50% of the information comes from invalid instruments. (5). MR Egger: Tests for and adjusts for pleiotropy, or the influence of genetic variants on multiple traits [36,37,38,39,40].

We used MR-PRESSO to detect and correct outliers in IVW linear regression and assessed heterogeneity using the Cochran Q test. If the Cochran Q test p-value was greater than 0.05, indicating no significant heterogeneity, we used the fixed-effects IVW method; otherwise, we used the random-effects IVW method. The analyses were performed using the Two Sample MR and MR-PRESSO packages in R [38].

Results

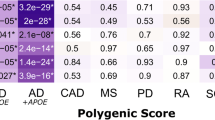

Immune cell types that confer protection against AD

We performed IVW (P < 0.01) as the main analysis, and the results indicated that 5 immune cells had a protective effect on AD (Fig. 1). We observed that the following immune cells were inversely associated with AD risk: CD28 on CD45RA- CD4 not Treg (0.9164, [0.8605–0.9758], 0.0064), CD3 on CM CD8br (0.9224, [0.8685–0.9797], 0.0086), CD4 Treg AC (0.9192, [0.8741–0.9667], 0.0010), HLA DR on CD14- CD16 + monocyte (0.9277, [0.8867–0.9707], 0.0011), SSC-A on HLA DR + CD8br (0.9305, [0.8836-0.9800], 0.0064).

Immune cell types that increase the risk of AD

We performed the main analysis using the IVW method(P < 0.01), which revealed that 7 immune cell markers were genetically predicted to be positively associated with AD: CD38 on IgD- CD38br (1.0301, [1.0109–1.0497], 0.0020),HLA DR on CD14 + CD16- monocyte (1.0608, [1.0158–1.1078], 0.0077),HLA DR on CD14 + monocyte (1.0624, [1.0157–1.1111], 0.0083), HVEM on T cell (1.0663, [1.0187–1.1161], 0.0059), IgD on IgD + CD24+ (1.0625, [1.0214–1.1053], 0.0026),IgD on IgD + CD38- unsw mem (1.0651, [1.0138–1.1190], 0.0123),IgD on IgD + CD38br (1.0769, [1.0255–1.1309], 0.0030) (Fig. 2).

Sensitivity analysis

We assessed the presence of horizontal pleiotropy, which occurs when some genetic variants used as IVs have direct effects on the outcome that are not mediated by the exposure, using the MR-Egger intercept and MR-PRESSO methods. We also evaluated the heterogeneity of causal estimates across IVs using the Cochran Q statistic in the MR-Egger method. We considered evidence of pleiotropy or heterogeneity if the P value was lower than 0.05 (Table 1). In addition, we conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to detect any influential IVs on the main results and ensure the robustness of the MR results. The results of the pleiotropy and sensitivity analysis are presented in Table 1. The overall direction of the results of several other sensitivity analyses agreed with the IVW point estimates. We did not detect heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy using Cochrane Q-analysis and MR-PRESSO global tests, respectively, indicating that the IVW results were reliable (Table 1).

Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive cognitive impairment, memory loss, and behavioral changes [1, 2]. The pathogenesis of AD is complex and multifactorial, involving genetic, environmental, and immunological factors [41]. Previous studies have indicated that immune cells are involved in modulating the inflammatory and immune responses in the brain, which may influence the amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition, tau phosphorylation, neuronal damage, and synaptic dysfunction in AD [42, 43].

Our study employed an exhaustive Mendelian randomization analysis to explore potential causal associations between 731 immune cell phenotypes and the risk of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Our analysis revealed that out of these, five immune cell traits appear to confer protection against AD, while seven immune cell traits were associated with an increased risk. The implicated immune cell traits spanned a broad range of T cells, B cells, monocytes, myeloid cells, and dendritic cells, underscoring the multifaceted and complex role of the immune system in AD pathogenesis. Our data suggest that both components of the immune response, namely innate and adaptive immunity, play significant roles in the etiopathogenesis of AD. Furthermore, different immune cell subsets may have unique or even opposing roles in modulating inflammation and immunity within the brain.

The protective immune cell traits against AD encompassed CD4 Treg AC, HLA DR on CD14- CD16 + monocyte, SSC-A on HLA DR+, CD8br CD28 on CD45RA- CD4 not Treg, CD3 on CM CD8br. These traits may mitigate the risk of AD through various mechanisms, potentially including inflammation suppression, augmentation of Aβ clearance, stimulation of neurogenesis, or maintenance of synaptic plasticity. For example, Tregs are recognized for their anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory functions, which they exert by secreting cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β, expressing molecules such as CTLA-4 and PD-1, or directly killing effector T cells [44]. Prior research has shown that enhancing the quantity or function of CD4 Tregs can ameliorate AD pathology and cognitive impairment [45,46,47].

In addition, classical monocytes, alternatively labeled as HLA DR + CD14- CD16 + monocytes, differentiate into macrophages or dendritic cells, and execute phagocytosis. They also participate in antigen presentation and immune regulation [48]. Earlier studies have indicated that these monocytes can protect against neurodegeneration by enhancing Aβ clearance and promoting neurogenesis [49, 50].

Our analysis identifies specific subgroups of immune cells including CD38 on IgD- CD38br, IgD on IgD + CD24+, IgD on IgD + CD38br,IgD on IgD+, as potential risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease through Mendelian randomization analysis. These immune cell subsets may play crucial roles in neuroinflammation and neuronal damage, both of which are known to be intimately linked with the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease [51,52,53].

Our study has some limitations that should be considered. First, we applied a two-sample MR approach based on publicly available summary statistics from large GWAS cohorts. Therefore, we were unable to perform stratified analyses by sex, age, or other factors that may modify the associations between immune cell traits and AD risk. Second, we used a European ancestry population as the reference panel for both exposure and outcome GWAS. Therefore, our results may not be applicable to other ethnic groups or populations with different genetic backgrounds. Third, we used a relatively lenient threshold for selecting instrumental variables for each immune cell trait to increase the statistical power and avoid weak instrument bias. However, this may also increase the likelihood of false positives or horizontal pleiotropy. Fourth, we could not account for the potential interactions or synergies among different immune cell traits or other factors that may influence the immune system in AD. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution and validated by further studies.

We proposed some future directions and implications for further research. Future studies should include more immune cell types, larger and more diverse populations, more biomarkers, and functional experiments to elucidate the causal mechanisms of immune system and AD. Our results offer valuable insights for the prevention and treatment of AD by modulating the immune system.

Future aspect

The findings of this study open up new avenues for future research in Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding the distinct roles of different immune cell subsets in AD can pave the way for the development of novel therapeutic strategies that modulate the immune response to combat neurodegeneration. Future studies could focus on exploring the mechanisms through which these immune cell traits influence AD pathogenesis and progression. In addition, the potential therapeutic effects of enhancing the protective immune cell traits or inhibiting the harmful ones could be investigated in preclinical and clinical trials. Furthermore, the use of high-throughput technologies and multi-omics approaches can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the immune landscape in AD. Ultimately, these efforts could contribute to the development of personalized immunotherapies for AD, improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

Conclusion

Our study findings suggest that immune regulation is crucial for the pathogenesis of AD and provide novel insights into the potential targets for prevention and treatment of AD. The results were consistent across various sensitivity analyses that evaluated pleiotropy and heterogeneity. However, some limitations of this study should be acknowledged, such as the potential confounding by population stratification, the lack of validation in independent cohorts, and the possibility of reverse causation.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Deng Y, Ye L, Yu C, Yin C, Shi J, Gong Q. (2019). CZYH Alleviates β-Amyloid-Induced Cognitive Impairment and Inflammation Response via Modulation of JNK and NF-κB Pathway in Rats. Behavioural neurology, 2019, 9546761. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9546761.

Guo Q, Wang C, Xue X, Hu B, Bao H. SOCS1 mediates Berberine-Induced amelioration of Microglial activated States in N9 Microglia exposed to β amyloid. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021(9311855). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9311855.

Leo A, Tallarico M, Sciaccaluga M, Citraro R, Costa C. Epilepsy and Alzheimer’s Disease: current concepts and treatment perspective on two closely related pathologies. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2022;20(11):2029–33. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X20666220507020635.

Freyssin A, Rioux Bilan A, Fauconneau B, Galineau L, Serrière S, Tauber C, Perrin F, Guillard J, Chalon S, Page G. Trans ε-Viniferin decreases amyloid deposits with Greater Efficiency Than Resveratrol in an Alzheimer’s mouse model. Front Neurosci. 2022;15:803927. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.803927. PMID: 35069106; PMCID: PMC8770934.

Li W, Jiang J, Zou X, Zhang Y, Sun M, Jia Z, Li W, Xu J. The characteristics of arterial spin labeling cerebral blood flow in patients with subjective cognitive decline: the Chinese imaging, biomarkers, and lifestyle study. Front NeuroSci. 2022;16:961164. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.961164.

Agorastos A, Pervanidou P, Chrousos GP, Baker DG. Developmental trajectories of early life stress and trauma: a narrative review on neurobiological aspects beyond stress system dysregulation. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:118. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00118.

Smith KE, Pollak SD. Early life stress and development: potential mechanisms for adverse outcomes. J Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2020;12(1):1–15.

Kip E, Parr-Brownlie LC. Healthy lifestyles and wellbeing reduce neuroinflammation and prevent neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Front NeuroSci. 2023;17:1092537.

Liu YX, Yu Y, Liu JP, Liu WJ, Cao Y, Yan RM, Yao YM. Neuroimmune Regulation in Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy: the Interaction between the brain and peripheral immunity. Front Neurol. 2022;13:892480. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.892480.

Cao W, Zheng H. Peripheral immune system in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegeneration. 2018;13(1):1–17.

Stephenson J, Nutma E, van der Valk P, Amor S. Inflammation in CNS neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology. 2018;154(2):204–19.

Ott, B. R., Jones, R. N., Daiello, L. A., de la Monte, S. M., Stopa, E. G., Johanson, C. E., ... & Grammas, P. (2018). Blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier gradients in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 10, 245.

Heneka MT, O’Banion MK. Inflammatory processes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184(1–2):69–91.

Deczkowska A, Amit I, Schwartz M. Microglial immune checkpoint mechanisms. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(6):779–86.

Jucker M, Walker LC. Alzheimer’s disease: from immunotherapy to immunoprevention. Cell. 2023;186(20):4260–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.021.

Jorfi M, Maaser-Hecker A, Tanzi RE. The neuroimmune axis of Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med. 2023;15(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-023-01155-w.

Song C, Shi J, Zhang P, Zhang Y, Xu J, Zhao L, Zhang R, Wang H, Chen H. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease: targeting β-amyloid and beyond. Translational Neurodegeneration. 2022;11(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-022-00292-3.

Jevtic S, Sengar AS, Salter MW, McLaurin J. The role of the immune system in Alzheimer disease: etiology and treatment. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;40:84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2017.08.005.

Li C, Ren J, Zhang M, Wang H, Yi F, Wu J, Tang Y. The heterogeneity of microglial activation and its epigenetic and non-coding RNA regulations in the immunopathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(10):511.

Wang L, Yu CC, Liu XY, Deng XN, Tian Q, Du YJ. (2021). Epigenetic modulation of microglia function and phenotypes in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Plasticity, 2021.

Carriero F, Rubino V, Leone S, Montanaro R, Brancaleone V, Ruggiero G, Terrazzano G. Regulatory TR3-56 cells in the Complex Panorama of Immune activation and regulation. Cells. 2023;12(24):2841. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12242841.

Planas-Fontánez TM, Sainato DM, Sharma I, Dreyfus CF. Roles of astrocytes in response to aging, Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis. Brain Res. 2021;1764:147464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2021.147464.

Marvar PJ, Harrison DG. Inflammation, immunity and the autonomic nervous system. Primer on the autonomic nervous system. Academic; 2012. pp. 325–9.

Arlehamn CSL, Garretti F, Sulzer D, Sette A. Roles for the adaptive immune system in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. Curr Opin Immunol. 2019;59:115–20.

Wu KM, Zhang YR, Huang YY, Dong Q, Tan L, Yu JT. The role of the immune system in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;70:101409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101409.

Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyg070.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):512–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv080.

Didelez V, Sheehan N. Mendelian randomization as an instrumental variable approach to causal inference. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(4):309–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280206077743.

Didelez V, Meng S, Sheehan NA. (2010). Assumptions of IV methods for observational epidemiology.

Zotova E, Bharambe V, Cheaveau M, Morgan W, Holmes C, Harris S, Neal JW, Love S, Nicoll JA, Boche D. Inflammatory components in human Alzheimer’s disease and after active amyloid-β42 immunization. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 9):2677–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt210.

Boche D, Donald J, Love S, Harris S, Neal JW, Holmes C, Nicoll JA. Reduction of aggregated tau in neuronal processes but not in the cell bodies after Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(1):13–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-010-0705-y.

Solerte SB, Ceresini G, Ferrari E, Fioravanti M. Hemorheological changes and overproduction of cytokines from immune cells in mild to moderate dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: adverse effects on cerebromicrovascular system. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(2):271–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00105-6.

Orrù, V., Steri, M., Sidore, C., Marongiu, M., Serra, V., Olla, S., Sole, G., Lai, S., Dei, M., Mulas, A., Virdis, F., Piras, M. G., Lobina, M., Marongiu, M., Pitzalis, M., Deidda, F., Loizedda, A., Onano, S., Zoledziewska, M., Sawcer, S., ? Cucca, F. (2020). Complex genetic signatures in immune cells underlie autoimmunity and inform therapy. Nature genetics, 52(10), 1036–1045. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-0684-4.

Bowden J, Spiller W, Del Greco MF, Sheehan N, Thompson J, Minelli C, et al. Improving the visualization, interpretation and analysis of two-sample summary data mendelian randomization via the radial plot and radial regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(4):1264–78.

Yokoyama, J. S., Wang, Y., Schork, A. J., Thompson, W. K., Karch, C. M., Cruchaga, C., ... & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2016). Association between genetic traits for immune-mediated diseases and Alzheimer disease. JAMA neurology, 73(6), 691–697.

Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(7):658–65.

Burgess S, Thompson SG. Bias in causal estimates from mendelian randomization studies with weak instruments. Stat Med. 2011;30(11):1312–23.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):512–25.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40(4):304–14.

Hartwig FP, Smith D, G., Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(6):1985–98.

Chen YG. Research progress in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Chin Med J. 2018;131(13):1618–24.

Yokoyama, J. S., Wang, Y., Schork, A. J., Thompson, W. K., Karch, C. M., Cruchaga, C., ... & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2016). Association between genetic traits for immune-mediated diseases and Alzheimer disease. JAMA neurology, 73(6), 691–697.

Wu KM, Zhang YR, Huang YY, Dong Q, Tan L, Yu JT. The role of the immune system in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;70:101409.

Tang, T. T., Zhu, Z. F., Wang, J., Zhang, W. C., Tu, X., Xiao, H., Du, X. L., Xia, J. H., Dong, N. G., Su, W., Xia, N., Yan, X. X., Nie, S. F., Liu, J., Zhou, S. F., Yao, R., Xie, J. J., Jevallee, H., Wang, X., Liao, M. Y., ?Cheng, X. (2011). Impaired thymic export and apoptosis contribute to regulatory T-cell defects in patients with chronic heart failure. PloS one, 6(9), e24272. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024272.

Fessler J, Ficjan A, Duftner C, Dejaco C. The impact of aging on regulatory T-cells. Front Immunol. 2013;4:231. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2013.00231.

Saresella M, Calabrese E, Marventano I, Piancone F, Gatti A, Calvo MG, Nemni R, Clerici M. PD1 negative and PD1 positive CD4 + T regulatory cells in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD. 2010;21(3):927–38. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-091696.

Srinivasan J, Lancaster JN, Singarapu N, Hale LP, Ehrlich LIR, Richie ER. Age-related changes in Thymic Central Tolerance. Front Immunol. 2021;12:676236. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.676236.

Sampath P, Moideen K, Ranganathan UD, Bethunaickan R. Monocyte subsets: phenotypes and function in tuberculosis infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1726. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01726.

Zuroff L, Daley D, Black KL, Koronyo-Hamaoui M. Clearance of cerebral Aβ in Alzheimer’s disease: reassessing the role of microglia and monocytes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:2167–201.

Thériault P, ElAli A, Rivest S. The dynamics of monocytes and microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:1–10.

Bulati, M., Buffa, S., Martorana, A., Gervasi, F., Camarda, C., Azzarello, D. M., ... & Colonna-Romano, G. (2015). Double Negative (IgG + IgD − CD27−) B Cells are Increased in a Cohort of Moderate-Severe Alzheimer’s Disease Patients and Show a Pro-Inflammatory Trafficking Receptor Phenotype. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 44(4), 1241–1251.

Martorana, A., Balistreri, C. R., Bulati, M., Buffa, S., Azzarello, D. M., Camarda, C., ... & Colonna-Romano, G. (2014). Double negative (CD19 + IgG + IgD − CD27−) B lymphocytes: a new insight from telomerase in healthy elderly, in centenarian offspring and in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Immunology letters, 162(1), 303–309.

Bulati, M., Buffa, S., Candore, G., Caruso, C., Dunn-Walters, D. K., Pellicanò, M., ... & Romano, G. C. (2011). B cells and immunosenescence: a focus on IgG + IgD − CD27−(DN) B cells in aged humans. Ageing research reviews, 10(2), 274–284.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The general program of Shandong Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2021MH373), the Joint Fund of Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2021LZY044), Jinan “GaoXiao 20 Tiao” Funding Project Contract (No. 2020GXRC005), Qilu Health Leading Talent Project, Lu Wei Talent Word [2020] No. 3, NATCM’s Project of High-level Construction of Key TCM Disciplines(zyyzdxk-2023116), and the fifth batch of National Research and Training Program for Outstanding Clinical Talents of Traditional Chinese Medicine (National Letter of TCM Practitioners No. 1 (2022)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Min Shen conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. Linlin Zhang, Chen Chen, Xiaocen Wei implemented the study. Yuning Ma, and Yuxia Ma reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, M., Zhang, L., Chen, C. et al. Investigating the causal relationship between immune cell and Alzheimer’s disease: a mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Neurol 24, 98 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-024-03599-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-024-03599-y