Abstract

Background

Deterioration of fine motor control of the tongue is common in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and has a major impact on quality of life. However, the underlying neuronal substrate is largely unknown. Here, we aimed to explore the association of tongue motor dysfunction in MS patients with overall clinical disability and structural brain damage.

Methods

We employed a force transducer based quantitative-motor system (Q-Motor) to objectively assess tongue function in 33 patients with MS. The variability of tongue force output (TFV) and the mean applied tongue force (TF) were measured during an isometric tongue protrusion task. Twenty-three age and gender matched healthy volunteers served as controls. Correlation analyses of motor performance in MS patients with individual disease burden as expressed by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and with microstructural brain damage as measured by the fractional anisotropy (FA) on Diffusion Tensor Imaging were performed.

Results

MS patients showed significantly increased TFV and decreased TF compared to controls (p < 0.02). TFV but not TF was correlated with the EDSS (p < 0.04). TFV was inversely correlated with FA in the bilateral posterior limb of the internal capsule expanding to the brain stem (p < 0.001), a region critical to tongue function. TF showed a weaker, positive and unilateral correlation with FA in the same region (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Changes in TFV were more robust and correlated better with disease phenotype and FA changes than TF. TFV might serve as an objective and non-invasive outcome measure to augment the quantitative assessment of motor dysfunction in MS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Articulatory dysfunction and swallowing disorders are common in multiple sclerosis (MS) and affect up to 60 % of patients [1–3]. The tongue is critically involved in both articulatory function and swallowing. Consequently, it has been suggested that tongue motor function might serve as a surrogate for dysarthria and dysphagia [4, 5]. Indeed, MS patients display reduced tongue muscle strength, premature fatigue, and slowing during repetitive movements even before clinical dysarthria emerges [6]. However, it is not known how these deficits are linked to overall disease burden and the neuropathological substrate of the disease.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has evolved as a reliable method to quantify the severity of brain tissue damage in MS. Specifically, reductions of the fractional anisotropy (FA) in the cerebral white matter have consistently been reported in MS patients [7]. In this vein, we have found previously that decreased FA in the cerebral white matter adjacent to sensory and visual cortices was linked to increased grip force variability in patients with MS [8].

Here, we utilized a force transducer based experimental setup to objectively quantify deficits in the fine motor control of the tongue in a cohort of MS patients and explored whether these deficits were associated with overall clinical disability and brain microstructural integrity.

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-three patients with the diagnosis of MS were recruited through the Department of Neurology at the University Hospital of Muenster. Their mean age was 38.8 years (SD +/−10.5, range 19–61), 23 were females. The mean EDSS was 3.8 (+/−1.9, range 1–7.5). Eighteen patients suffered from relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), 11 from secondary progressive MS (SPMS) and 4 from primary progressive MS (PPMS). Twenty-three age-matched healthy control subjects (38.4 +/−9.3 years, range 24–55, 16 females) with no former history of neurological or psychiatric disease served as controls. Demographical and clinical data of MS patients and controls are summarized in Table 1. Prior to study participation, informed consent was obtained from each participant in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the local ethics committee at the University Clinic of Muenster. The majority of MS patients and all control subjects have been part of a previously published study investigating grip force control in MS [8].

Isometric tongue force assessment (Glossomotography)

The experimental setup of the Q-Motor “glossomotography” device (QuantiMedis GmbH, Muenster, Germany) has been described in detail elsewhere [9]. Briefly, the subjects protruded their tongue to establish contact with a circular pre-calibrated force transducer mounted on a glossomotograph. The subjects had clear sight at a monitor positioned 30 cm in front of the apparatus. A horizontal line indicated the target force. Subjects were instructed to match the indicated force level by generating an appropriate isometric tongue protrusion force. Each trial lasted 30 s, a cueing tone signaled start and end of each trial. Five trials each were performed at a target force level of 0.5 [N]. Data was sampled at 400 Hz, stored and analyzed on a laboratory computer system (SC/ZOOM, University of Umea, Sweden). The applied mean tongue protrusion force (TF) and the tongue force variability (TFV; defined as the coefficient of variation: SD(TF)/TF×100[%]) were measured during the static phase from second 10 to 30 of each trial. Values obtained from each subject were averaged across trials and entered into statistical analyses.

DTI protocol and data processing

28 of the 33 MS patients were available for DTI imaging as described previously [8]. Controls did not undergo MRI. MRI was conducted using a 3 T whole-body scanner (Gyroscan Intera T30, Philips, Netherlands). Data were acquired using a single shot echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence in 72 axial slices (1.8 mm thick, no gap, FOV 230 × 230 mm, acquired matrix 127 × 128, b factors: 0 and 1,000 s/mm2 6 gradient directions, 3 averages). For further processing all EPI images were reconstructed to 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm3. All images were spatially registered by the multicontrast image registration toolbox for optimal spatial pre-processing of DTI data prior to statistical analysis [10] and corrected for eddy currents in all three dimensions using a recently developed technique [11, 12]. After image registration, all DTI images corresponded to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinate space. Following registration, data were spatially smoothed (4 mm FHWM).

FA maps for each subject were calculated and voxel based statistics were applied using SPM (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Correlational analyses of tongue force measures with FA maps were performed on a voxel by voxel basis using the “simple regression” model implemented in SPM. We applied a voxel threshold of p < 0.001, cluster level corrected at p < 0.05. The cluster extend cutoff was set at 50 voxels. For post-hoc volume of interest (VOI) analysis, FA values were extracted from 4 mm spheres centered at the peak voxel of each cluster revealed by the voxel wise searches and correlated with behavioral measures.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS®. The Student’s t-test was used for intergroup comparisons of behavioral data between MS patients and healthy controls. The Spearman correlation coefficient was applied for correlation of TF and TFV measures with the EDSS. Post-hoc regression analyses of regional DTI measures with TF and TFV, respectively, were carried out using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Results were considered as significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Intergroup comparisons

TFV was significantly increased in MS patients (35.5+/−18.7 [%] (mean+/−SD)) compared to controls (24.7+/−7.1 [%]; p < 0.02; Fig. 1a left). In contrast, TF was significantly decreased in the MS group (0.36+/−0.08 [N] vs. 0.40+/−0.04 [N]; p < 0.02; Fig. 1a right). Notably, TFV and TF were inversely correlated in patients (r = −0.89, p < 0.001; Pearson correlation coefficient), whereas we did not observe a significant correlation of these measures in the control group (p > 0.16).

a Group comparisons of tongue force variability (TFV) and mean applied tongue force (TF) between patients with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and normal controls (NL) during an isometric tongue protrusion task. Compared to NL, TFV was significantly increased in MS patients, whereas TF was significantly decreased in the latter group. b TFV in MS patients correlated with the overall disease burden as assessed by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Bars express group mean values; the error bars indicate the SEM

Correlation to disease severity

We found a moderate correlation of TFV with the EDSS (r = 0.36, p < 0.04) (Fig. 1b). TF did not correlate with the EDSS (p > 0.10).

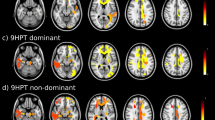

Correlation of behavioral measures with FA

TFV was inversely correlated with FA in a region encompassing the posterior limb of the internal capsule expanding to the brain stem (Fig. 2a, top). Given the inverse relationship of TFV with TF, not surprisingly, we observed a positive, albeit weaker correlation of TF with FA unilaterally in the posterior portion of the right internal capsule (Fig. 2b, top). Post-hoc VOI analysis confirmed a significant correlation of FA with TFV and TF in the posterior internal capsule (p < 0.001; Fig. 2 a/b, bottom panels).

Correlation of tongue force variability (TFV) and mean tongue force (TF) with fractional anisotropy (FA) in 28 patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Results were superimposed on a standard FA template. a Symmetric, negative correlations were found between TFV and FA in the posterior limb of the internal capsule expanding to the brain stem. b TF exhibited a positive correlation with FA in the right internal capsule only. Post-hoc analyses of individual FA values extracted from volumes of interest centered at the peak voxel of each cluster confirmed significant correlations of FA with TFV (a bottom panels) and TF (b bottom panel). aCoordinates are displayed in the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard space; the colored bar indicates the T-values; voxel threshold p < 0.005

Discussion

We found an increased variability of force output and concurrent reductions of the applied mean force during an isometric tongue protrusion task in MS patients. These findings are in line with previous studies reporting reductions of the voluntary force output and increased force variability in MS patients in a variety of motor tasks [8 ,13, 14]. We have found earlier that the variability of force output showed higher sensitivity than the mean applied force in assessing alterations of motor hand function in MS and other neurological conditions, particularly when deterioration of motor performance was still mild [8, 15, 16]. Along these lines, it is noteworthy that TFV but not TF was associated with overall disability and also exhibited stronger correlations with FA measures. These findings further support the hypothesis of force variability being superior over mean applied force to quantify motor dysfunction and its association to microstructural brain damage in MS [8].

FA measures the degree to which overall diffusion of water molecules can be described as anisotropic. FA ranges from 0–1, where 0 indicates completely isotropic diffusion with no contribution of anisotropic diffusion. FA typically is high (i.e. diffusion is predominantly anisotropic) in brain regions rich in myelinated fibers such as the pyramidal tract or corpus callosum and relatively low (i.e. diffusion is predominantly isotropic) in gray matter areas [17]. While other DTI metrics (e.g. axial and radial diffusivity) have been reported in addition to FA, the latter might be the DTI measure best established and most widely utilized to assess white matter integrity and its association with clinical disability in MS (see e.g.[17, 18] for review). We deliberately chose to measure FA for correlational analyses with behavioral data based on our prior findings. In the latter study, we explored the association of altered hand motor function with cerebral white matter integrity. We found that only FA in the white matter adjacent to the primary sensory and visual cortices, but not other DTI measures, i.e. mean diffusivity, axial diffusivity and radial diffusivity, correlated with quantitative measures of hand motor function, suggesting that FA might be most sensitive to assess white matter damage associated with motor dysfunction.

Supporting these findings, TFV was inversely correlated with FA in the posterior limb of the internal capsule expanding to the brain stem, whereas TF showed a positive correlation with FA in this region. Thus, decreased microstructural white matter integrity was indicative of abnormally high tongue force variability and reduced total force output in the MS patients. The posterior portion of the internal capsule mainly incorporates cortico fugal motor fibers comprising the pyramidal and corticobulbar tracts, and somatosensory fibers. The motor fibers have a somatotopic organization with the tongue being located in the anterior part of the posterior limb [19, 20]. Hence, structural damage of this structure, particularly its anterior portion, is likely to affect tongue function by disrupting motor output from the motor cortex to the tongue [21].

Dysphagia and dysarthria are common in MS. A recent meta-analysis conducted by Guan et al. showed that at least one third of MS patients suffer from dysphagia [22]. Similar estimates have been suggested for dysarthria in MS patients [1]. Dysphagia can emerge in very early disease stages in ambulatory patients, and constitutes a major hazard in severely affected patients. Several studies established a close relationship between overall clinical disability and the presence of dysphagia, suggesting that dysphagia is most pronounced in clinically severely affected patients with an EDSS of 6.5 or higher [2, 3]. Whereas dysphagia is associated with overall clinical disability, it seems that the MS subtype is not a strong predictor of dysphagia [23]. However, reports are equivocal and some authors suggest that patients with progressive MS forms (SPSS and PPMS) are more likely to develop dysphagia compared to patients with RRMS [24]. Similarly, the severity of dysarthria has been found to correlate well with overall disease burden [25], even though subtle signs of dysarthria have been revealed in MS patients without manifest speech disorder [1]. In line with these findings, we found that MS patients with high EDSS scores exhibited pronounced variability of tongue force output.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. Because of the limited sample size we could not explore potential differences in FA and its correlation with tongue function for the MS subtypes in the current set of data. Moreover, the correlations observed do not necessarily imply a causal relationship of structure and function and the specificity of the findings reported remains unclear because healthy controls did not undergo MRI. That said, the strong and symmetric correlations of TFV with FA in a region crucial to tongue motor function are intriguing and indicate a link of increased TFV to the neuropathological substrate of the disease. Previous reports suggest that both dysarthria and dysphagia are associated with overall disease burden rather than alterations of single functional systems or subtype of MS [22, 26]. That being said, for future studies, it might be worthwhile to additionally apply clinical rating scales specifically assessing dysphagia and dysarthria. Finally, we note that FA is very sensitive to microstructural brain changes per se [11, 27], but is limited in characterizing the pathological processes underpinning these structural alterations. For example, FA changes in afferent pathways can be caused by both potentially reversible demyelination and irreversible axonal degeneration in patients with MS [28]. A multi-modal imaging approach including myelin sensitive MRI techniques might help to better understand the pathological processes underlying microstructural tissue damage [29, 30].

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the quantitative motor (Q-Motor) measurement of tongue function might proof useful as a non-invasive and cost efficient method to assess motor dysfunction in MS in addition to categorical scales such as the EDSS. Avoidance of inter- and intra-rater variability and lack of site-effects due to the pre-calibration of sensors applied may increase sensitivity and reliability, e.g., in small proof-of-concept studies. In line with prior studies [8, 9] TFV was a more sensitive surrogate of motor dysfunction and more robustly linked to overall disease burden and microstructural brain integrity than TF. Prospective studies are warranted to prove the utility of TFV to assess longitudinal changes of motor phenotype and cerebral microstructure in patients with MS.

References

Hartelius L, Runmarker B, Andersen O. Prevalence and characteristics of dysarthria in a multiple-sclerosis incidence cohort: relation to neurological data. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2000;52(4):160–77.

De Pauw A, Dejaeger E, D'Hooghe B, Carton H. Dysphagia in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2002;104(4):345–51.

Calcagno P, Ruoppolo G, Grasso MG, De Vincentiis M, Paolucci S. Dysphagia in multiple sclerosis - prevalence and prognostic factors. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;105(1):40–3.

Hartelius L, Lillvik M. Lip and tongue function differently affected in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2003;55(1):1–9.

Weijnen FG, Kuks JB, van der Bilt A, van der Glas HW, Wassenberg MW, Bosman F. Tongue force in patients with myasthenia gravis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102(5):303–8.

Murdoch BE, Spencer TJ, Theodoros DG, Thompson EC. Lip and tongue function in multiple sclerosis: A physiological analysis. Mot Control. 1998;2(2):148–60.

Filippi M, Rocca MA, De Stefano N, Enzinger C, Fisher E, Horsfield MA, et al. Magnetic resonance techniques in multiple sclerosis: the present and the future. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(12):1514–20.

Reilmann R, Holtbernd F, Bachmann R, Mohammadi S, Ringelstein EB, Deppe M. Grasping multiple sclerosis: do quantitative motor assessments provide a link between structure and function? J Neurol. 2013;260(2):407–14.

Reilmann R, Bohlen S, Klopstock T, Bender A, Weindl A, Saemann P, et al. Tongue force analysis assesses motor phenotype in premanifest and symptomatic Huntington's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(13):2195–202.

Mohammadi S, Keller SS, Glauche V, Kugel H, Jansen A, Hutton C, et al. The influence of spatial registration on detection of cerebral asymmetries using voxel-based statistics of fractional anisotropy images and TBSS. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e36851.

Deppe M, Kellinghaus C, Duning T, Moddel G, Mohammadi S, Deppe K, et al. Nerve fiber impairment of anterior thalamocortical circuitry in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Neurology. 2008;71(24):1981–5.

Mohammadi S, Moller HE, Kugel H, Muller DK, Deppe M. Correcting eddy current and motion effects by affine whole-brain registrations: evaluation of three-dimensional distortions and comparison with slicewise correction. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(4):1047–56.

de Haan A, de Ruiter CJ, van Der Woude LH, Jongen PJ. Contractile properties and fatigue of quadriceps muscles in multiple sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23(10):1534–41.

Krishnan V, Jaric S. Hand function in multiple sclerosis: force coordination in manipulation tasks. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119(10):2274–81.

Reilmann R, Bohlen S, Klopstock T, Bender A, Weindl A, Saemann P, et al. Grasping premanifest Huntington’s disease - shaping new endpoints for new trials. Mov Disord. 2010;25(16):2858–62.

Tabrizi SJ, Reilmann R, Roos RA, Durr A, Leavitt B, Owen G, et al. Potential endpoints for clinical trials in premanifest and early Huntington’s disease in the TRACK-HD study: analysis of 24 month observational data. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(1):42–53.

Fox RJ. Picturing multiple sclerosis: conventional and diffusion tensor imaging. Semin Neurol. 2008;28(4):453–66.

Ge Y, Law M, Grossman RI. Applications of diffusion tensor MR imaging in multiple sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1064:202–19.

Duerden EG, Finnis KW, Peters TM, Sadikot AF. Three-dimensional somatotopic organization and probabilistic mapping of motor responses from the human internal capsule. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(6):1706–14.

Pan C, Peck KK, Young RJ, Holodny AI. Somatotopic organization of motor pathways in the internal capsule: a probabilistic diffusion tractography study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(7):1274–80.

Titelbaum DS, Sodha NB, Moonis M. Transient hemiglossal denervation during acute internal capsule infarct in the setting of dysarthria-clumsy hand syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(7):1266–7.

Guan XL, Wang H, Huang HS, Meng L. Prevalence of dysphagia in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(5):671–81.

Poorjavad M, Derakhshandeh F, Etemadifar M, Soleymani B, Minagar A, Maghzi AH. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010;16(3):362–5.

Bergamaschi R, Crivelli P, Rezzani C, Patti F, Solaro C, Rossi P, et al. The DYMUS questionnaire for the assessment of dysphagia in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2008;269(1–2):49–53.

Darley FL, Brown JR, Goldstein NP. Dysarthria in multiple sclerosis. J Speech Hear Res. 1972;15(2):229–45.

Hartelius L, Theodoros D, Cahill L, Lillvik M. Comparability of perceptual analysis of speech characteristics in Australian and Swedish speakers with multiple sclerosis. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2003;55(4):177–88.

Meinzer M, Mohammadi S, Kugel H, Schiffbauer H, Floel A, Albers J, et al. Integrity of the hippocampus and surrounding white matter is correlated with language training success in aphasia. Neuroimage. 2010;53(1):283–90.

Kolappan M, Henderson AP, Jenkins TM, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Plant GT, Thompson AJ, et al. Assessing structure and function of the afferent visual pathway in multiple sclerosis and associated optic neuritis. J Neurol. 2009;256(3):305–19.

Kolind S, Matthews L, Johansen-Berg H, Leite MI, Williams SC, Deoni S, et al. Myelin water imaging reflects clinical variability in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2012;60(1):263–70.

Freund P, Weiskopf N, Ashburner J, Wolf K, Sutter R, Altmann DR, et al. MRI investigation of the sensorimotor cortex and the corticospinal tract after acute spinal cord injury: a prospective longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(9):873–81.

Acknowledgements

This study was not funded. Q-Motor (“glossomotography”) devices and analysis can be made available for studies & collaborations (contact: ralf.reilmann@ghi-muenster.de). We thank all research participants for their contribution to this project. FH work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, HO 5034/1-1). SM work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, MO 2397/1-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

RR has provided consulting services, advisory board functions, clinical trial services, quantitative motor (Q-Motor) analyses, and/or lectures for: Novartis, Siena Bitoech, Neurosearch Inc., Ipsen, Teva, Lundbeck, Medivation, Pfizer, Wyeth, ISIS Pharma, Link Medicine, Prana Biotechnology, the Cure Huntington’s Disease Initiative Foundation, MEDA Pharma, Temmler Pharma, and AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals AG. He is the founding director of the “George-Huntington-Institute” and has several responsibilities in the European Huntington’s Disease Network (member of the “Executive Committee” and the “Clinical trials task force”, Lead Facilitator of the Neuroprotective Therapy and Motor Phenotype Working Groups). Dr. Reilmann has received grant support from the High-Q-Foundation, the Cure Huntington’s Disease Initiative Foundation (CHDI), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the European Union (EU-FP7) and the European Huntington’s Disease Network (EHDN).

Authors’ contributions

FH participated in study design, carried out tongue force assessments, carried out statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript MD participated in MRI data processing and analysis and revised the manuscript RB acquired the MRI data, was involved in data analysis and revised the manuscript SM was involved in MRI data analysis and revised the manuscript EBR participated in study design and revised the manuscript RR participated in study design, carried out the clinical assessments, was involved in data analysis and drafted the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Holtbernd, F., Deppe, M., Bachmann, R. et al. Deficits in tongue motor control are linked to microstructural brain damage in multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. BMC Neurol 15, 190 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-015-0451-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-015-0451-9