Abstract

Background

Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) has a high prevalence among persons with HIV infection. Since Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs) are used worldwide and have been associated with weight gain, we must determine their effect in the development of NAFLD and Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) in these patients. The aim of this study was to explore the impact of INSTIs on variation of liver steatosis and fibrosis in the ART-naïve person with HIV, using Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI), Fibrosis-4 Index (FIB-4), BARD score and NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS).

Methods

We performed a monocentric, retrospective cohort study in ART-naïve persons with HIV that initiated INSTI based regimens between December 2019 and January 2022. Data was collected at baseline, 6 and 12 months after initiation. Demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics, hepatic steatosis, and fibrosis scores were compared between baseline and last visit at 12 months. Linear regression models were performed to analyse the associations between analytical data at baseline and hepatic scores variation during the 12 months of treatment. Models were performed unadjusted and adjusted for age and sex.

Results

99 patients were included in our study. 82% were male and median age was 36 years. We observed a significant increase in body mass index (BMI), HDL, platelet count, albumin, and creatinine and a significant decrease in AST levels. HSI showed no statistically significant differences during follow-up (p = 0.114). We observed a significant decrease in FIB-4 (p = 0.007) and NFS (p = 0.002). BARD score showed a significant increase (p = 0.006). The linear regression model demonstrated a significant negative association between baseline HIV RNA and FIB-4 change (β= -0.08, 95% CI [-0.16 to -0.00], p = 0.045), suggesting that higher HIV RNA loads at baseline were associated with a greater decrease in FIB-4.

Conclusion

INSTIs seem to have no impact on hepatic steatosis, even though they were associated with a significant increase in BMI. This might be explained by the direct effect of a dolutegravir-containing regimen and/or by the “return-to-health effect” observed with ART initiation. Furthermore, INSTIs were associated with a reduction in risk of liver fibrosis in ART-naïve persons with HIV, possibly due to their effect on viral suppression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Improvements in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection treatment has shifted the priorities in the clinical care of patients with this infection. Due to the increased access to combined Antiretroviral Therapy (ART), mortality amongst persons with HIV has declined and life expectancy has been approaching that of the general population. Even though it remains the leading cause of death in this group of patients, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)-related mortality has decreased, hence increasing the importance of non-AIDS related morbidities, such as non-AIDS cancers, liver disease, cardiovascular diseases, and stroke [1, 2].

Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) is characterized by evidence of hepatic steatosis, without secondary causes for hepatic fat accumulation, and is related to metabolic comorbidities. NAFLD is divided into two categories, Non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFL is defined as the presence of steatosis in ≥ 5% of hepatocytes without hepatocyte ballooning. NASH is defined as the presence of steatosis in ≥ 5% of hepatocytes and inflammation with hepatocyte injury, associated or not to fibrosis [3].

Although the true prevalence of NAFLD in persons with HIV is still unknown, Maurice et al. showed a prevalence of NAFLD and NASH, in these patients, of 35% and 42%, respectively [4]. According to Vodkin et al., there is a higher proportion of NASH and features of more severe liver injury in patients with HIV-associated NAFLD, when compared with patients with primary NAFLD, despite having similar metabolic characteristics [5].

Multiple risk factors have been associated with the development of NAFLD in persons with HIV. These include factors that also have an association with NAFLD in the general population, such as male sex, obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and insulin resistance. However, factors associated with HIV itself, such as lipodystrophy and ART, contribute to the disease as well [6, 7].

Previous studies have suggested the contribution of ART in the development of hepatic steatosis, due to its metabolic side effects [8]. In particular, various HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) have been associated with higher levels of insulin resistance. Most PIs, some Non-Nucleoside Reverse-Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs) such as efavirenz and some Nucleoside/nucleotide Reverse-Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs) such as abacavir have been related to dyslipidemia. Stavudine and didanosine have been shown to induce mitochondrial toxicity, which also contributes to the development of NASH [9].

Bischoff et al., demonstrated that the use of Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs) and/or Tenofovir-alafenamid (TAF) contributes to the occurrence of hepatic steatosis and progression to NASH, in the context of increased body weight [10].

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for identifying both NASH and NAFLD. However, it has various limitations, as it is an invasive procedure with high costs, low acceptability, and sampling variability. Therefore, multiple non-invasive strategies have been studied and developed, as alternatives to this technique, including blood biomarkers and imaging techniques [11]. Scores based on blood biomarkers available to diagnose or grade steatosis include the Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI), and to stage fibrosis include NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS) and BARD, which are more specific of NAFLD, and Aspartate Transaminase (AST)/Alanine Transaminase (ALT) Ratio and Fibrosis-4 Index (FIB-4), which have been developed in the context of hepatitis C [12].

According to the European Association for the Study of the Liver-European Association for the Study of Diabetes-European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASL-EASD-EASO) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NFS, FIB-4, Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) or FibroTest calculation should be performed in every NAFLD patient to exclude significant fibrosis. If fibrosis is not excluded, then transient elastography should be performed. Only if this exam confirms significant fibrosis, should liver biopsy be done in order to establish the final diagnosis [13].

Currently, INSTIs are recommended worldwide as first line treatment in HIV infection [14]. With the growing number of patients under this treatment and the high prevalence of liver disease in persons with HIV, it becomes essential to determine the effect of these drugs in the development of NAFLD and liver fibrosis.

Therefore, we performed a retrospective cohort study with the aim of evaluating the impact of INSTIs on variation of steatosis and fibrosis biomarkers, using HSI, FIB-4, BARD and NFS indexes, in persons with HIV infection.

Methods

Subjects

We performed an observational monocentric, retrospective cohort study in persons with HIV followed at the Infectious Diseases Outpatient Clinic of Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João. This study included all treatment-naïve adults (age ≥ 18 years) that initiated an INSTI based regimen between December 2019 and January 2022 and maintained it during at least 12 months. Exclusion criteria were Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and/or Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) infection, determined by HCV antibody testing and HBV surface antigen positivity, pregnancy at the beginning or during follow-up and excessive alcohol use, based on the self-reported alcohol consumption by the patients. This study was approved by Comissão de Ética para a Saúde do Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João and the requirement for a signed informed consent was waived.

Clinical assessment

For each patient the following information was collected: demographic data (age, sex), clinical comorbidities, such as Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and smoking history, time since HIV diagnosis, HIV infection risk factors, duration of ART, ART regimen and the degree of the infection. We used the “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention” (CDC) criteria for classifying the degree of the infection [15]. Diabetes Mellitus diagnosis was determined using a combination of diagnostic code and use of antidiabetic medication. Weight and height were measured in routine consultation at baseline, before starting ART, and during follow-up. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated automatically using the formula: weight (kg) / height (m2). These data were collected through clinical records stored at the hospital’s electronic platform.

Laboratory analysis

Serum samples were tested at baseline, before starting ART (T0), and six months (T6) and twelve months (T12) after initiating ART. CD4+ T cell count in cells/mm3, type 1 HIV Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) in copies/mL, platelet count in 103/µL, albumin in g/L, AST in U/L, ALT in U/L, total bilirubin in mg/dL, total cholesterol in mg/dL, High-density Lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in mg/dL, Low-density Lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in mg/dL, Triglycerides (TG) in mg/dL, fasting glucose in mg/dL, creatinine in mg/dL, uric acid in mg/dL, and C Reactive Protein (CRP) levels in mg/dL were retrieved from clinical records through the hospital’s electronic platform.

Hepatic steatosis and fibrosis evaluation

The HSI values were calculated automatically using the formula: 8 x (ALT/AST ratio) + Body Mass Index (BMI) (+ 2, if female; +2, if diabetes mellitus). The categories considered were NAFLD ruled out with HSI < 30.0 and NAFLD detected with HSI > 36.0 [16].

The FIB-4 values were calculated automatically using the formula: age (years) × AST [U/l] / (platelets [109/l] ×\(\surd\) (ALT [U/l])). FIB-4 < 1.45 was considered as no or moderate fibrosis (F0-F1-F2-F3), and FIB-4 > 3.25 was considered as extensive fibrosis or cirrhosis (F4-F5-F6) (in the ISHAK classification of fibrosis) [17].

The BARD score was calculated as BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 (1 point) + AST/ALT ratio ≥ 0.8 (2 points) + presence of diabetes (1 point). The categories considered were low risk of advanced fibrosis (0–1 score) or high risk of advanced fibrosis (2–4 score) [18].

The NFS values were calculated automatically using the formula: -1.675 + (0.037 x age [years]) + (0.094 x BMI [kg/m2]) + (1.13 x IFG/diabetes [yes = 1, no = 0]) + (0.99 x AST/ALT ratio) – (0.013 x platelet count [×109/L]) – (0.66 x albumin [g/dl]). We divided the individuals in categories based on NFS score as low risk of advanced fibrosis with NFS<-1,455, intermediate risk with NFS between − 1,455 and 0,672 and high risk with NFS > 0,672 [12].

Statistical analysis

Demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics and hepatic steatosis and fibrosis scores were compared between baseline and last visit at 12 months. Categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous variables were expressed as means (standard deviation), if normally distributed, or as median (25th to 75th percentile), if non-normally distributed. Variables with skewed distribution were transformed to their natural logarithm.

Persons with missing baseline or follow-up data for the variables needed to calculate each score were excluded from the analysis of the respective score.

Differences in continuous variables between baseline and the last visit were assessed using paired t-test or Wilcoxon test, according to the distribution of the variables. McNemar test was used for categorical data.

Linear regression models were performed to analyse the associations between analytical data at baseline and the hepatic scores variation during the 12 months of treatment. Regression models were performed unadjusted and adjusted for age [19] and sex [20].

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

The manuscript was prepared in adherence to the STROBE guidelines for cohort studies [21].

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

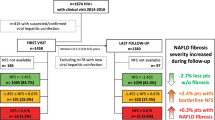

Overall, as demonstrated in Fig. 1, 99 patients were included in our analysis, both at baseline and through follow-up, until last visit at 12 months. 82% were male, and the median age was 36 years (28 to 50). (Table 1) The most frequent routes of transmission were men who have sex with men (60.4%) and heterosexual contact (29.7%). 39% of patients had a nadir CD4 cell count < 200/ µL and 17.2% were diagnosed as having HIV stage C.

We were able to calculate BMI at baseline and/or at last visit only in 68 patients, due to weight and height data availability. At baseline, overweight, defined by a BMI of at least 25 and less than 30 kg/m2, was observed in 19 (27.9%) patients, and obesity, defined by a BMI of at least 30 kg/m2, was observed in 4 (5.9%).

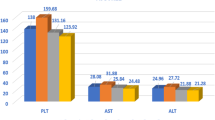

We observed a significant increase in BMI, HDL, platelet count, albumin, and creatinine during follow-up. Furthermore, we observed a significant decrease in AST levels.

Hepatic fibrosis and steatosis scores

We were able to calculate the BARD and HSI scores on either T0 or T12 in 68 patients and on both visits in 59 patients. We were able to calculate the NFS score in 67 patients on at least one of the visits and in 50 patients on both T0 and T12. We were able to calculate the FIB-4 score in 94 patients on at least one of the visits and in 92 patients on both visits. We compared the baseline characteristics of the sample that had all the hepatic steatosis and fibrosis scores available in the first visit (n = 59) with the baseline characteristics of the individuals without at least one of these scores (n = 40) and observed that the characteristics of the individuals were similar between these groups and similar to the whole cohort (see Additional file 1).

The median HSI values were 31.30 (26.78 to 34.82) at baseline and 31.48 (28.21 to 36.37) at the last visit, showing no statistically significant differences (p = 0.114). The median difference in HSI score between baseline and last visit was 0.56 (-1.33 to 2.30). HSI scores < 30, ruling out the presence of NAFLD, were observed in 31 (46.27%) and 26 (38.24%) of patients at baseline and last visit, respectively. HSI values > 36, indicating presence of NAFLD, were observed in 13 (19.40%) and 17 (25.00%) of patients at baseline and last visit, respectively.

The median FIB-4 values were 1.02 (0.64 to 1.40) at baseline and 0.79 (0.60 to 1.20) at the last visit, showing a significant decrease (p = 0.007). The median difference in FIB-4 values between baseline and last visit was − 0.058 (-0.357 to 0.097). FIB-4 values < 1.45, indicating none or moderate fibrosis, were observed in 71 (76.34%) and 78 (82.98%) of patients at baseline and last visit, respectively. FIB-4 values > 3.25, indicating extended fibrosis or cirrhosis, were observed in 4 (4.30%) and 3 (3.19%) of patients at baseline and last visit, respectively.

The mean of BARD scores was 1.82 (0.85) at baseline and 2.09 (0.73) at the last visit, showing a significant increase of this score during follow-up (p = 0.006). The mean difference in BARD values between baseline and last visit was 0.37 (0.93). Eleven (16.4%) and 5 (7.4%) patients had BARD scores of either 0 or 1, representing a low risk for advanced fibrosis, at baseline and last visit, respectively. BARD scores between 2 and 4, representing a high risk of advanced fibrosis, were observed in 56 (83.6%) and 63 (92.7%) patients at baseline and last visit, respectively. However, only 13 (22%) patients had a different BARD score value between baseline and last visit. 46 (78%) patients showed no alteration in BARD score.

The median NFS values were − 1.95 (-3.35 to -0.75) at baseline and − 2.15 (-3.29 to -1.16) at the last visit, displaying a significant decrease in this score (p = 0.002). The median difference in NFS values was − 0.42 (-0.93 to 0.18) between baseline and last visit. NFS scores <-1.455, indicating low risk of advanced fibrosis, were observed in 38 (63.3%) and 45 (66.2%) of patients at baseline and last visit, respectively. NFS values between − 1.455 and 0.672, representing intermediate risk, were found in 18 (30.0%) and 20 (29.4%) patients at baseline and last visit, respectively. NFS values > 0.672, indicating high risk of advanced fibrosis, were observed in 4 (6.67%) and 2 (2.94%) patients at baseline and last visit, respectively.

In Fig. 2, we show a decrease in FIB-4 and NFS throughout time, at baseline, 6 and 12 months, and an increase in BARD. HSI did not vary over time.

Boxplots and bar charts of liver steatosis and fibrosis scores at baseline, and 6 and 12 months after initiation of treatment with Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors.A, Box-plot of FIB-4 values at baseline (T0), 6 months (T6) and 12 months (T12) of follow-up; B, Bar chart of mean BARD values at T0, T6 and T12; C, Box-plot of NFS values at T0, T6 and T12; D, Box-plot of HSI values at T0, T6 and T12. * p < 0.05. Abbreviations: FIB-4, Fibrosis-4; HSI, Hepatic Steatosis Index; NFS, NAFLD Fibrosis Score.

Analytical predictors of changes in hepatic fibrosis scores

In the unadjusted linear regression model (Table 2), there was a significant negative association between baseline HIV RNA and FIB-4 change, suggesting that higher HIV RNA loads at baseline are associated with a decrease in FIB-4 (β=-0.08 [-0.16 to 0.00]; p = 0.045). After adjusting for age and sex, this association was no longer significant, although a trend for a negative association was found (β=-0.08 [-0.16 to 0.00]; p = 0.062).

A significant positive association was observed between total bilirubin at baseline and BARD score change (β = 1.09 [0.18 to 2.00]; p = 0.019 in the adjusted model), suggesting that higher baseline bilirubin is associated with an increase in BARD.

The unadjusted linear regression model showed no association between HDL and NFS change, but, when adjusted for age and sex, there was a significant positive association with NFS change (β = 0.03 [0.00 to 0.05]; p = 0.036), indicating that higher baseline HDL cholesterol is associated with an increase in NFS.

No associations were found between any of the fibrosis scores and CD4 cell count, fasting glucose, total and LDL cholesterol, TG and CRP.

Discussion

In our single-center retrospective assessment of previously naïve persons with HIV on an INSTI based regimen, we observed a significant decrease in the values of FIB-4 and NFS scores, which may indicate a reduction in the risk of developing fibrosis in these patients. Also, we found a significant negative association between HIV RNA load at baseline and FIB-4 variation between baseline and 12 months, suggesting higher HIV RNA at baseline was significantly associated with a greater decrease in FIB-4.

However, we did not find differences in the proportion of individuals in each score category between the first and the last visit, which may be due to the small sample of this study.

Although, we did not see any significant changes in the HSI, that would indicate a change in steatosis, our findings supported that NAFLD is highly prevalent in persons with HIV, as demonstrated in previous studies [4].

Macias et al. compared persons with HIV with NALFD who switched from efavirenz to raltegravir (RAL) with patients maintaining efavirenz-based therapy. After 48 weeks, they found that the patients who switched to RAL showed a reduction in the degree of hepatic steatosis, as measured by Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) as well as a greater proportion of patients without significant steatosis [22]. This study agrees with our findings in suggesting that INSTIs do not contribute to the progression of hepatic steatosis. However, we did not find a similar reduction in hepatic steatosis. The mentioned study measures hepatic steatosis using CAP, a much more sensitive method of evaluating this parameter when compared to the HSI score used in our study, which might explain the differences in results.

On the other hand, Bischoff et al. showed that patients receiving INSTIs had a greater development and progression of steatosis and evolution towards NASH, in relation to increased body weight gain, which is contrary to our findings [10]. Similarly, a prospective cohort study showed that INSTIs were related to greater odds of moderate-to-severe hepatic steatosis. However, they did not find this relation to be true for every INSTI. This association was present for exposure to elvitegravir and RAL, but not to dolutegravir (DTG), even though the patients receiving DTG had the highest weight gain [23].

In our study, the INSTI 96% of patients was receiving was DTG. This way, the previously mentioned study comes to support our findings, and propose a hypothesis as to why they are not congruent with previous studies, such as the one performed by Bischoff et al., in which INSTIs used are not specified. Although INSTIs appear to contribute to the progression of hepatic steatosis in persons with HIV, this might not be true for DTG, despite its effect on weight gain. Riebensahm et al. suggested the same explanation for their findings of lack of relation between INSTIs and hepatic steatosis [8]. Therefore, to support this claim, more studies comparing the various INSTIs and their individual effects on hepatic steatosis are needed.

The patients in the present study showed a significant increase in BMI, which could be explained by multiple factors. On the one hand, several studies demonstrated a greater weight gain in patients receiving INSTI based regimens, especially DTG and RAL, both in ART-naïve and ART-experienced patients [24, 25]. On the other hand, studies have shown that the initiation of ART in treatment-naïve persons with HIV is associated with a short period of weight gain. Considering this is true particularly in patients with lower baseline CD4 + T-cell count and higher HIV RNA viral load, this is consistent with a “return to health effect” [26, 27].

Contrary to the significant decrease in values of FIB-4 and NFS scores, we observed a significant increase in BARD score. These first two scores are continuous variables and BARD score is an ordinal variable, obtained from an addition of points. Although BARD score showed a significant increase, 80% of patients had the same BARD score at baseline and at the last visit, meaning differences were only visible in 13 patients out of 59 in total. Since the calculation of this score includes only BMI, AST/ALT ratio and the presence of diabetes, the fact that BMI showed a significant increase might have had a great impact in BARD score, possibly explaining its elevation. Such an impact would not be so visible in the other scores, since FIB-4 does not include BMI in its calculation and NFS is a much more complex index with various other liver function parameters. Additionally, McPherson et al. compared multiple simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems, including the three scores we used in our study, and found FIB-4 score to have the best diagnostic accuracy for advanced fibrosis, with an Area Under Receiver Operator Characteristic Curve (AUROC) of 0.86. The AUROC for NFS was 0.81 and 0.77 for BARD [28]. Imajo et al. compared elastography and various risk scores to histology and found NFS and FIB-4 to be better than other indexes, including BARD, in predicting advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD [29]. Accordingly, both the guidelines by the European Association for the Study of the Liver and by the American Association for the Study of the Liver Diseases advocated the use of FIB-4 and NFS to rule out advanced liver fibrosis [3, 13].

The decrease we observed in the risk of developing liver fibrosis, as demonstrated by the reduction in NFS and FIB-4 values, can probably be explained by the effects of ART in the suppression of HIV infection.

HIV infection alone contributes to the development of liver fibrosis, through multiple processes, such as mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, fatty acid accumulation, gut microbial translocation and immune-activation and proapoptotic effects on hepatocytes [30, 31]. With viral suppression from ART, these mechanisms are reduced, thus decreasing hepatic fibrosis markers and scores in the patients receiving treatment.

Our linear regression model supported this hypothesis by showing that higher HIV RNA at baseline was significantly associated with a greater decrease in FIB-4. This indicates that patients with a higher activity of HIV at baseline, and consequently more liver damage induced by the above-mentioned mechanisms, had a greater reduction in risk of fibrosis with the initiation of treatment. Therefore, these findings support the early initiation of ART.

Multiple previous studies come to support our conclusions, showing that effective ART and complete suppression of HIV replication prevents liver fibrosis development and that modern ART regimens have a negligible effect in its progression [32]. In addition, Blackard et al. found an association between plasma HIV RNA loads and increased FIB-4 in women with HIV with no ART or alcohol use, as well as a negative association between CD4 cell count and FIB-4 [33].

This was also true in HIV-coinfected patients, as shown by Bräu et al., who demonstrated that HIV suppression with ART led to a slower progression rate of HCV-induced fibrosis [34], and by Yang et al. who associated ART initiation with a significant reduction in fibrosis scores in HIV/HBV coinfected patients [35].

Therefore, our findings are more congruent with the effects of ART on viral suppression and may not give us a clear picture of its direct impact in hepatic fibrosis, suggesting the need for future studies in virologically suppressed persons with HIV who switch to INSTIs.

Additionally, the findings of our linear regression model suggested that higher baseline bilirubin is associated with an increase in BARD, which is in line with previous studies that associate advanced liver fibrosis with increased bilirrubin [36]. Furthermore, this model, when adjusted for age and sex, suggested that higher baseline HDL cholesterol is associated with an increase in NFS, which is contrary to what has been shown in prior studies that associate HDL to regeneration and suppression of liver fibrosis [37].

It has been demonstrated that HIV infection is associated with low levels of HDL and that these levels relate to HIV RNA [38, 39]. When further exploring our database, we also found that lower levels of HDL at baseline were related to higher HIV RNA loads. Therefore, a possible explanation for our model findings might be that the patients with higher HDL at baseline had a lower activity of the infection, thus having less effect of the HIV virus in the liver. Consequently, these patients might have had less benefit with the viral suppression exerted by the initiation of ART, showing no reduction in the fibrosis scores. The association with an increase in NFS can then be explained by the increase shown in BMI.

Our study had several limitations. It was a retrospective assessment of a small predominantly male cohort from one center in the north of Portugal, with no control group, therefore the results may not be generalizable to other populations. Our short follow-up time of 12 months allows us only to evaluate the short-term impact of the INSTIs and may underestimate their effect on liver steatosis and fibrosis on the long run. We used serum biomarkers to evaluate the presence of steatosis and fibrosis that have lower sensitivity and specificity than the gold standard test, liver biopsy, and we did not exclude patients with other liver diseases. Other limitations were present in the availability of patient’s data, possibly due to the COVID-19 period and the use of telephonic or virtual consultations. Weight and height information were not available for every patient at the three evaluation times, which led to BMI calculation only being possible in 59 patients. Additionally, only self-reported, not quantitatively specified, alcohol consumption was available, which might have led us to underestimate the presence of alcohol consumption in a small percentage of patients. Furthermore, data on waist and hip circumferences were not available. Consequently, we evaluated weight gain only considering BMI, which does not give information regarding the distribution of fat and presence of visceral fat, important factors in NAFLD.

Conclusion

In this monocenter cohort of persons with HIV, INSTIs had no impact on hepatic steatosis, mainly driven by the use of a DTG-containing regimen. Additionally, INSTIs were associated with a significant increase in BMI, that might be explained by the direct effect of DTG and/or by the “return-to-health effect” observed with ART initiation. Furthermore, INSTIs were associated with a reduction in the risk of liver fibrosis in persons with HIV, probably due to their effect on suppression of viral replication, perhaps demonstrating a protective action against fibrosis progression.

Therefore, our study highlights the need for early initiation of ART, namely INSTI, as well as a close monitorization of patients with NAFLD, a disease with high prevalence among persons with HIV, in order to prevent the progression towards NASH and liver fibrosis.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- ALT:

-

Alanine Transaminase

- AST:

-

Aspartate Transaminase

- AUROC:

-

Area Under Receiver Operator Characteristic Curve

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CAP:

-

controlled attenuation parameter

- ART:

-

combined Antiretroviral Therapy

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CRP:

-

C Reactive Protein

- DTG:

-

Dolutegravir

- EASL-EASD-EASO:

-

European Association for the Study of the Liver-European Association for the Study of Diabetes-European Association for the Study of Obesity

- ELF:

-

Enhanced Liver Fibrosis

- FIB-4:

-

Fibrosis-4 Index

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B Virus

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C Virus

- HDL:

-

High-density Lipoprotein

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HSI:

-

Hepatic Steatosis Index

- INSTIs:

-

Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors

- LDL:

-

Low-density Lipoprotein

- NAFL:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- NASH:

-

Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis

- NFS:

-

NAFLD Fibrosis Score

- NNRTIs:

-

Non-Nucleoside Reverse-Transcriptase Inhibitors

- NRTIs:

-

Nucleoside/nucleotide Reverse-Transcriptase Inhibitors

- PIs:

-

HIV protease inhibitors

- RAL:

-

Raltegravir

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic Acid

- T0:

-

Before starting ART

- T12:

-

Twelve months of follow-up

- T6:

-

Six months of follow-up

- TAF:

-

Tenofovir-alafenamid

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

References

Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, Morlat P, Pradier C, Reiss P, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. The Lancet. 2014;384(9939):241–8.

Croxford S, Kitching A, Desai S, Kall M, Edelstein M, Skingsley A, et al. Mortality and causes of death in people diagnosed with HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy compared with the general population: an analysis of a national observational cohort. The Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(1):e35–e46.

Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328–57.

Maurice JB, Patel A, Scott AJ, Patel K, Thursz M, Lemoine M. Prevalence and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in HIV-monoinfection. Aids. 2017;31(11):1621–32.

Vodkin I, Valasek MA, Bettencourt R, Cachay E, Loomba R. Clinical, biochemical and histological differences between HIV-associated NAFLD and primary NAFLD: a case-control study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2015;41(4):368 − 78.

Morse CG, McLaughlin M, Matthews L, Proschan M, Thomas F, Gharib AM, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatic fibrosis in HIV-1-Monoinfected adults with elevated aminotransferase levels on antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(10):1569–78.

Guaraldi G, Squillace N, Stentarelli C, Orlando G, D’Amico R, Ligabue G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in HIV-Infected patients referred to a metabolic clinic: prevalence, characteristics, and predictors. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(2):250–7.

Riebensahm C, Berzigotti A, Surial B, Günthard HF, Tarr PE, Furrer H et al. Factors Associated with Liver steatosis in people with human immunodeficiency virus on contemporary antiretroviral therapy. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2022;9(11).

Rockstroh JK. Non-alcoholic fatty liver Disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2017;14(2):47–53.

Bischoff J, Gu W, Schwarze-Zander C, Boesecke C, Wasmuth J-C, Van Bremen K, et al. Stratifying the risk of NAFLD in patients with HIV under combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101116.

Makri E, Goulas A, Polyzos SA, Epidemiology. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and emerging treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Arch Med Res. 2021;52(1):25–37.

Castera L, Friedrich-Rust M, Loomba R. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(5):1264–81e4.

EASL-EASD-EASO. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1388–402.

Organization WH. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery and monitoring: recommendations for a public health approach. World Health Organization; 2021.

Castro KG, Ward JW, Slutsker L, Buehler JW, Jaffe HW, Berkelman RL, et al. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(4):802–10.

Lee J-H, Kim D, Kim HJ, Lee C-H, Yang JI, Kim W, et al. Hepatic steatosis index: a simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Disease. 2010;42(7):503–8.

Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V, et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. Comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology. 2007;46(1):32–6.

Harrison SA, Oliver D, Arnold HL, Gogia S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut. 2008;57(10):1441–7.

McPherson S, Hardy T, Dufour J-F, Petta S, Romero-Gomez M, Allison M, et al. Age as a confounding factor for the accurate non-invasive diagnosis of advanced NAFLD fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(5):740.

Yang JD, Abdelmalek MF, Pang H, Guy CD, Smith AD, Diehl AM, et al. Gender and menopause impact severity of fibrosis among patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1406–14.

Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):31.

Macías J, Mancebo M, Merino D, Téllez F, Montes-Ramírez ML, Pulido F, et al. Changes in liver steatosis after switching from Efavirenz to Raltegravir among Human Immunodeficiency virus–infected patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(6):1012–9.

Kirkegaard-Klitbo DM, Thomsen MT, Gelpi M, Bendtsen F, Nielsen SD, Benfield T. Hepatic steatosis associated with exposure to elvitegravir and raltegravir. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(3):e811–e4.

Bourgi K, Jenkins CA, Rebeiro PF, Shepherd BE, Palella F, Moore RD, et al. Weight gain among treatment-naïve persons with HIV starting integrase inhibitors compared to non‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors or protease inhibitors in a large observational cohort in the United States and Canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(4):e25484.

Kileel EM, Lo J, Malvestutto C, Fitch KV, Zanni MV, Fichtenbaum CJ, et al. editors. Assessment of obesity and cardiometabolic status by integrase inhibitor use in REPRIEVE: a propensity-weighted analysis of a multinational primary cardiovascular prevention cohort of people with human immunodeficiency virus. Open forum infectious diseases; 2021: Oxford University Press US.

Yuh B, Tate J, Butt AA, Crothers K, Freiberg M, Leaf D, et al. Weight change after antiretroviral therapy and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(12):1852–9.

Grant PM, Kitch D, McComsey GA, Collier AC, Bartali B, Koletar SL, et al. Long-term body composition changes in antiretroviral-treated HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2016;30(18):2805.

McPherson S, Stewart SF, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2010;59(9):1265–9.

Imajo K, Kessoku T, Honda Y, Tomeno W, Ogawa Y, Mawatari H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging more accurately classifies steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease than transient elastography. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(3):626–37. e7.

Kaspar MB, Sterling RK. Mechanisms of liver disease in patients infected with HIV. BMJ open gastroenterology. 2017;4(1):e000166.

Kovari H, Weber R. Influence of antiretroviral therapy on liver disease. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6(4):272–7.

Mohr R, Schierwagen R, Schwarze-Zander C, Boesecke C, Wasmuth JC, Trebicka J, et al. Liver fibrosis in HIV Patients receiving a modern cART: which factors play a role? Med (Baltim). 2015;94(50):e2127.

Blackard JT, Welge JA, Taylor LE, Mayer KH, Klein RS, Celentano DD, et al. HIV mono-infection is associated with FIB-4 - a noninvasive index of liver fibrosis - in women. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):674–80.

Bräu N, Salvatore M, Ríos-Bedoya CF, Fernández-Carbia A, Paronetto F, Rodríguez-Orengo JF, et al. Slower fibrosis progression in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients with successful HIV suppression using antiretroviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2006;44(1):47–55.

Yang R, Gui X, Ke H, Xiong Y, Gao S. Combination antiretroviral therapy is associated with reduction in liver fibrosis scores in patients with HIV and HBV co-infection. AIDS Res Therapy. 2021;18:1–9.

Jarčuška P, Janičko M, Veselíny E, Jarčuška P, Skladaný Ľ. Circulating markers of liver fibrosis progression. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411(15–16):1009–17.

Ding B-S, Liu CH, Sun Y, Chen Y, Swendeman SL, Jung B et al. HDL activation of endothelial sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 (S1P1) promotes regeneration and suppresses fibrosis in the liver. JCI insight. 2016;1(21).

Njoroge A, Guthrie BL, Bosire R, Wener M, Kiarie J, Farquhar C. Low HDL-cholesterol among HIV-1 infected and HIV-1 uninfected individuals in Nairobi, Kenya. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16(1):110.

Bernal E, Masiá M, Padilla S, Gutiérrez F. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol in HIV-Infected patients: evidence for an Association with HIV-1 viral load, antiretroviral therapy status, and Regimen Composition. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22(7):569–75.

Acknowledgements

Non applicable.

Funding

Non applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.F. contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the patient data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. A.L. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the patient data and in writing the manuscript. R.L. and A.G. contributed to the acquisition of data. C.P., R.S. and P.F. drafted the work and substantively revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Comissão de Ética para a Saúde do Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João. (Project number 27/2023).

The requirement for a signed informed consent was waived by Comissão de Ética para a Saúde do Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João.

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the world Health Organization, the Oviedo Convention and the ICH guideline for good clinical practice.

Consent for publication

Non applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional file 1

: Comparison of baseline characteristics of cohort with and without all liver scores available at baseline

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernandes, S.R., Leite, A.R., Lino, R. et al. The impact of integrase inhibitors on steatosis and fibrosis biomarkers in persons with HIV naïve to antiretroviral therapy. BMC Infect Dis 23, 553 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08530-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08530-3