Abstract

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) chronicity in the midst of old age multiplies the risk for chronic non communicable diseases. The old are predisposed to drug-drug interactions, overlapping toxicities and impairment of the quality of life (QoL) due to age-related physiological changes. We investigated polypharmacy, QoL and associated factors among older HIV-infected adults at Muhimbili National hospitals in Dar es Salaam Tanzania.

Methods

A hospital-based cross sectional study enrolled adults aged 50 years or older who were on antiretroviral therapy (ART) for ≥ 6 months. Participants’ Information including the number and type of medications used in the previous one week were recorded. Polypharmacy was defined as concurrent use of five or more non-HIV medications. A World Health Organization QoL questionnaire for people living with HIV on ART (WHOQoL HIV BREF) was used to assess QoL. A score of ≤ 50 meant poor QoLwhile > 50 meant good QoL. Polypharmacy and QoL are presented as proportions and compared using Chi-square test. Association between various factors and polypharmacy or QoL was assessed using modified Poisson regression. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 285 patients were enrolled. The mean (SD) age was 57(± 6.88) years. Females were the majority (62.5%), and 42.5% were married. Polypharmacy was seen in 52 (18.2%) of participants. Presence of co-morbidities was independently associated with polypharmacy (p < 0.001). The mean(SD) score QoL for the study participants was 67.37 ± 11.Poor QoL was seen in 40 (14%) participants.All domains’ mean score were above 50, however social domain had a relatively lowmean scoreof 68 (± 10.10). Having no formal or primary education was independently associated with poor QoL (p = 0.021).

Conclusion

The prevalence of polypharmacy was modestly high and was linked to the presence of co-morbidities. No formal and/or primary education was associated with poor QoL, where by social domain of QoL was the most affected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) is still a global burden despite intensive efforts to stop the chain of transmission. In the year 2021, Globally 38.4 million people were living with HIV, 28.7 million people were accessing antiretroviral therapy, 1.5 million people became newly infected and 650 000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses [1].

In the year 2019, Tanzania had an estimated 1.7 million people living with HIV (PLWHIV), making a prevalence of 4.8% among people aged 15–49 years. As it has been over the past years, women were more affected (6.0%) than men (3.6%). The country reported 27,000 AIDS-related deaths despite having ART coverage of about 75% among all adults living with HIV [2]. The data for the year 2020 was more or less comparable to 2019 data, with a report of about 58,000 new infections, 50% of these were among youths aged 15–29 years [3]. A cross-sectional study in northern Tanzania by Swai et al. (2015) reported a prevalence of HIV to be 1.7% among people aged 50 years or older in year [4].

Knowing that Anti-Retroviral Therapy (ART) has transformed HIV disease from a deadly disease to a chronic manageable condition [5, 6], it is irrefutable that ART has increased life expectancy among PLWHIV [7]. PLWHIV are now living longer to experience age-related co-morbidities like diabetes, arthritis, and cardiovascular diseases thus expose them to multiple drugs use [8]. HIV by itself and its treatment are associated with a number of non-communicable diseases such as atherosclerosis, arterial stiffening, hypertension, dyslipidemia and thus may result into complications associated with cardiovascular diseases [9,10,11]. Cardiovascular complications associated with HIV and its treatment includes acute coronary syndrome, stroke, and vascular diseases. Other co-morbidities are intestinal and renal diseases and many others. [12]. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) are known to have side effects like ischaemic heart disease, peripheral neuropathy and pancreatitis; Protease inhibitors (PIs) do cause hyperlipidemia, diabetes and hepatitis. [13]. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate may cause chronic kidney disease which may be worse enough to necessitate renal replacement therapy [14, 15].

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines polypharmacy in a general population as the use of five or more drugs [16]. Among HIV infected individuals who are on ART, the WHO defines polypharmacy as the concurrent use of five or more non-HIV medications [17, 18].

Polypharmacy is among the burdens faced by HIV infected individuals on ART [17]. It is observed more in older adults, including those on ART [19, 20], possibly because older adults receiving ART are faced with both age-related (non-HIV) and HIV-related co-morbidities [8, 21].

Polypharmacy increases chances of drug-drug interactions and hence adverse drug effects to both the young and the old, however old PLWHIV are more at risk for side effects of polypharmacy hence vulnerable to geriatric syndromes [19, 22,23,24,25]. Old people have altered pharmacokinetics due to reduced residual function of different body organs [26, 27], The main mechanisms involved in drug-drug interactions among PLWHIV on ART are those which affect the pharmacokinetics of drugs at different stages including absorption, protein binding, hepatic metabolism and drug transporter molecules [26]. Age-related co-morbid conditions are the leading factors contributing to polypharmacy [27, 28]. Regardless of the presence of age-related co-morbidities, polypharmacy has been found to be associated with increased risk of falls, fractures, frailty, delirium, pills burden and hence poor medication use [29,30,31] and poor quality of life (QoL) outcomes. Medication side effects have been reported to be the main cause of care dissatisfaction [32], an entity largely linked to polypharmacy. Furthermore polypharmacy is associated with poor patient satisfaction, reduced QoL and poor clinical outcomes including poor viral load suppression and immunological improvement [31].

Polypharmacy among the elderly may be minimized in a number of ways which include thorough medications history, review of indication for the current medications, good communication with healthcare providers, review of drug-drug interaction and determination of therapeutic ratio [27].

In Tanzania, there is scarcity of data on the magnitude of polypharmacy, associated factors and its effect on health-related QoL among HIV-infected older adults on ART. This study was done to inform on the burden and risk factors for polypharmacy and its impact on the QoL among older adults on ART.

Methods

Study design and study area

This was a hospital-based cross sectional study conducted at Muhimbili National Hospital situated in Dar es Salaam city, Tanzania from July 2021 to December 2021. It is the largest tertiary hospital in the country with two campuses Upanga and Mloganzila. It also serves as a teaching hospital for the Muhimbili University of Health and allied sciences. CTC clinic at MNH Upanga provides care for both children and adults with more than 3000 enrolled PLWHIV. In Mloganzila campus, the CTC had enrolled about 300 clients. The two clinics operate for 5 days in a week i.e. Mondays to Fridays excluding public holidays.

Study population

All HIV-infected out-patients aged 50 years or older, on ART for 6 months or more attending care and treatment clinics at Muhimbili National Hospital, Upanga and Mloganzila campuses. We excluded participants who did not provide consent and the very sick who needed emergency care as it wasn’t possible to interview them.

Study procedures

Participants were informed about what the study was all about and asked for their consent to participate. Consenting participants were enrolled consecutively until the required sample size was attained. Data was collected using a face-to-face interviewer-administered structured questionnaire inquiring about socio-demographic and clinical data including co-morbidities and number of medications (including supplements) they were using concomitantly with their ART in the past one week. Participants were also required to provide their active phone contacts at the time of interviews. Those who were not able to recall their medications at the time of interview were contacted later via their phone contact to send names (for those without smart phones) or pictures of the medication leaflets and/or packages to be able to ascertain the number and type of medications they were using. Traditional medications were not counted since their chemical composition and effect/drug-drug interactions are un-predictable.

We recorded information on co-morbid conditions and the number of other regular clinics participants were attending. A short version of the World Health Organization (WHO) QoL questionnaire for HIV-infected patients on ART (WHO QoL-HIV BREF) was used to assess participants’ QoL. The WHOQoL-HIV BREF has six domain scores made up of 29 items plus two items inquiring about individuals’ general QoL(Overall QoL and health perception) which then makes a total of 31 items. The six domains include physical health (4 items), psychological well-being (5 items), level of independence (4 items), social relation (4 items),environmental health (8 items), and spiritual health (4 items).Individual items were rated on a 5-point likert scale where 1 indicates low, negative perception and 5 indicate high, positive perceptions. In such a way, domain scores are scaled in a positive direction where higher scores denote higher QoL. However, seven facets are not scaled in a positive direction, meaning that for those facets, higher scores do not denote higher QoL. Those facets are re-coded in a positive direction so that high scores reflect better QoL. For instance, to what extent do you feel that physical pain prevents you from doing what you need to do? Options are 1-Not at all, 2-A little 3-A moderate amount 4-Very much and 5-An extreme amount. Facets like these were reversed into a positive direction so that 1 be an extreme amount in that order to 5-Not at all hence the higher scores will result into a good QoL. There are two questions of the WHOQoL-HIV BREF that examines the general QoL: question 12 asks about an individual’s overall perception of the QoL and question 13 asks about an individual’s overall perception of health. The first domain, physical health, deals with the presence of pain and discomfort, energy and fatigue, sleep and rest, and symptoms related to HIV. The psychological domain comprises negative and positive feelings, thinking, memory and concentration, body image and appearance, and self-esteem. Independent domain consists of mobility, activities of daily living, dependence on medication or treatments, and work capacity. The social relationships domain describes; personal relationships, social support, and sexual activity. Physical safety and security, home environment, financial resources, physical environment, and opportunities for acquiring new information were described under the environment domain. The last domain, spiritual health, contains information about concern about future death, forgiveness, and blame. There is also a general facet that measures the overall QoL of an individual (2 items asking individuals on the perception of their QoL and general health perception). The standard two weeks’ time frame was used to derive the patient's QoL experience.

As per the questionnaire authors’ suggestion, domain scores were calculated by computing the mean of the facet score within the respective domain and eventually multiplied by 4 to make domain scores comparable with the scores used in the WHO QoL-100 (WHOQOL-100), a commonly used scale [5, 33, 34].

Accordingly, the scores range from 4 to 20 points, reflecting the worst and the best QoL, respectively. The WHOQoL-HIV BREF user’s manual was rigorously followed for scoring and checking domain scores and score were transformed to the one that are found in the WHOQOL-100 then analyzed.

Data analysis

Data entry, cleaning and analysis was done using SPSS statistical software version 23. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Mean and standard deviation was calculated for continuous variables. Prevalence of polypharmacy is reported as percentage. Study participants were divided into two groups; those with good QoL (WHO QoL-HIV BREF mean scores of > 50) and those with poor QoL (mean scores of ≤ 50) in overall QoL and general health perceptions facets.

Chi-square test was used to denote the association between independent variables (socio-demographic and clinical characteristics) and the outcomes of interest (polypharmacy and health related QoL (HRQoL). Univariate analysis using Poisson modified Poisson regression model was used to assess for the association between independent variables and the outcome of interest. Variables with p value of < 0.20 in the bivariate modified Poisson regression analysis were taken to the multivariate modified Poisson regression analysis. A p-value of < 0.05 in the multivariate model was considered statistically significant.

Results

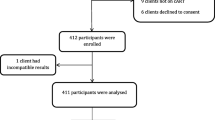

Figure 1 shows participants’ recruitment flow. A total of 298 PLWHIV aged 50 years or older and who were on ART for 6 months or more were screened for eligibility. Two hundred and eighty five participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were enrolled into the study.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of 285 study participants. The mean age (± standard deviation) of study participants was 57(± 6.88) years. A total of 178 (62.5%) of the participants were female. Majority 266 (93.3%)of the study participants were residing in Dar es Salaam, were married 121 (42.5%) and had primary level education 142 (49.8%). Most 233 (81.8%) of the study participants were attending care and treatment clinics at Muhimbili national hospital, Upanga campus.

Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy

The prevalence of polypharmacyin this study population was found to be 18.2% (52/285).

Polypharmacy among older adults living with HIV on ART was found to be significantly associated with increasing number of co-morbidities, attendance to clinic(s) other than CTC and number of clinics attended other than CTC, all with a p value ≤ 0.001. There was no difference on the prevalence of polypharmacy between participants aged 50–64 years (16.9%) and those aged 65 years or older (26.6%), male (18.7%) and female (18.0%) participants, across the marital statuses or education level categories, all having p value > 0.05 (Table 2).

Predictors of polypharmacy were the number of co-morbidities, attendance of clinics other than the HIV clinic and thenumber of clinics participants had to attend. Compared to participants with no co-morbidities, the risk for polypharmacy was 18 times more among those with co-morbidities, PR (95% CI) = 18.09 (7.47–43.78), p < 0.001 (Table 3).

Health related QoL and their predictors among older adult PLWHIV on ART

The overall QoL was good, WHOQoL HIV BREF mean (\(\pm \mathrm{SD}\)) score was 67.37 ± 11. Of the 285 participants, 40 (14%) reported poor QoL. Poor QoL was significantly more prevalent among participants with no formal or primary level of education (18.4%) compared to those with secondary or post-secondary education(9.0%), p = 0.023, among those with two or more co-morbidities (28.6%) compared to those with one (4.3%) and those without co-morbidities (15.4%), p < 0.01, and among participants who attended two or more clinics other than the CTC (27.6%) compared to those who attended the HIV clinic only (15.4%), p < 0.01 (Table 4).

Having no formal or primary education was the only factor that was associated with poor quality of life in univariate regression model for the study population. Multivariate regression analysis for predictors of QoL was not performed because only education qualified for that analysis (Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of polypharmacy among older adults PLWHIV on ART for 6 months or more was high at 18.2%. Polypharmacy was associated with increasing number of co-morbidities, attendance to clinic(s) other than CTC & number of clinics attended other than CTC. Polypharmacy was not associated with age, sex, marital status or education level. Only presence of co-morbidities could predict polypharmacy. Nearly ninety percent of the participants in the present study reported an overall good QoL. Having no formal education or primary education predicted poor QoL in the present study.

The prevalence of polypharmacy in this study was lower compared to a study done in Morogoro rural area in Tanzania which found the prevalence to be 24% among adults PLWHIV on ART [25]. The observed relatively lower prevalence in the present study could be due to differences in time periods the two studies were conducted, rural versus urban setting, socio-economic and the study population differences. One study in Uganda among HIV adults aged 50 years or older reported a prevalence of polypharmacy to be 15.3% [19] which is almost similar to the findings of our study. Other studies have reported different prevalence due to age, geographical, socio-economic factors and methodological difference with our study. For example a study done in Switzerland among Swiss HIV cohort aged 50 years or older found the prevalence of polypharmacy to be 31.8% [21].

Although not significant in the present study, polypharmacy was more prevalent among participants aged 65 years or older as compared to younger participants. Increasing age was found to be associated with polypharmacy in other studies [17, 35,36,37].

High prevalence of polypharmacy among older adults PLWHIV on ART in these studies are believed to be due to several possible reasons including differences in methodological approach [36, 38], racial differences and having health insurance [37]. The same observation has also been reported among HIV uninfected people aged 65 years or older [39, 40].

In the present study we found that having co-morbid conditions was independently associated with polypharmacy. This could be explained by the fact that, these co-morbidities which are both HIV related and non-HIV related do co-exist, with non-HIV related co-morbidities being on the rise due to increased life expectancy among PLWHIV [41,42,43]. Apart from individual factors that contribute to polypharmacy among this group there are also health system, facility-based and clinician factors including development on new therapies, increased preventive measures, medical guidelines and prescribing habits of the attending clinician [40, 44].

In the present study, the participants who reported poor QoL had the social domain of QoL most affected. The social domain can be affected by HIV-related stigma [45], not being sexually active and societal discrimination [46]. No formal and/or primary education level was found to be associated with poor QoL after controlling for other factors. Education level in the present study might have been confounded by other factors like unemployment and low income which weren’t checked in the present study.

Contrary to findings in other studies [5, 33], having co-morbidities was not associated with poor QoL in the present study. This could be because of differences in the study settings. For instance, a study by Zeleke et al.was done among admitted patients with HIV/AIDs in selected hospitals while the present study was done among relatively stable outpatients withHIV infection attending CTC [5]. In another study by Passos et al., the co-morbidities assessed were a bit different from those assessed in our study and this could be the main reason for disagreement between the studies. In the study by Passos et al., co-morbidities that were assessed included Hypertension, Diabetes, dyslipidemia, tuberculosis, hepatitis, CKD, COPD and cancer [33].

Strength of the study

This study used a disease specific WHO tool to assess QoL among older adults PLWHIV on ART.

Limitation of the study

As the study required participants to remember the number of medications in the past one week and QoL facets two weeks ago there was a possibility of recall bias.

Conclusion

The prevalence of polypharmacy was high among older adults living with HIV. Polypharmacy was associated with increasing number of co-morbidities, attendance to clinic(s) other than CTC & number of clinics attended other than CTC. Having no formal education or primary education was found to be an independent determinant of poor QoL.

We recommend synchronization of treatment and care for HIV and HIV-unrelated co-morbidities in order minimize polypharmacy.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset is available from the corresponding author.

References

Sheet F, Hiv N, Hiv N. Global HIV statistics. 2022. p. 1–6.

AVERT Global information and education on HIV and AIDS. HIV and AIDS in Key affected populations. 2017; Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/asia-pacific/india#footnote2_7i7ga58

Monitoring GA. 2020 Progress reports submitted by countries - United Republic of Tanzania. 2020; Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2020countries

Swai SJ, Damian DJ, Urassa S, Temba B, Mahande MJ, Philemon RN, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for HIV among people aged 50 years and older in Rombo district. Northern Tanzania Tanzan J Health Res. 2017;19(2):1–8.

ZelekeNegera G, Ayele MT. Health-related quality of life among admitted HIV/AIDS patients in selected ethiopian tertiary care settings: a cross-sectional study. Open Public Health J. 2020;12(1):532–40.

Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, Halter JB, Hazzard WR, Horne FMF, et al. Workshop on HIV infection and aging: What is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):542–53.

Manuscript A. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):293–9.

Krentz HB, Cosman I, Lee K, Ming JM, Gill MJ. Original article Pill burden in HIV infection : 20 years of experience. Antivir Ther. 2012;840:833–40.

de Gaetano Donati K, Cauda R, Iacoviello L. HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy and cardiovascular risk. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2010;2(3):e2010034.

Defo AK, Chalati MD, Labos C, Fellows LK, Mayo NE, Daskalopoulou SS. Association of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2021;78(2):320–32.

Cerrato E, D’Ascenzo F, Biondi-Zoccai G, Calcagno A, Frea S, Grosso Marra W, et al. Cardiac dysfunction in pauci symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus patients: a meta-analysis in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(19):1432–6.

Islam FM, Wu J, Jansson J, Wilson DP. Relative risk of renal disease among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):234. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/234

Chawla A, Wang C, Patton C, Murray M. A review of long-term toxicity of antiretroviral treatment regimens and implications for an aging population. Infect Dis Ther. 2018;7(2):183–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-018-0201-6.

Mtisi TJ, Ndhlovu CE, Maponga CC, Morse GD. Tenofovir-associated kidney disease in Africans: A systematic review. AIDS Res Ther. 2019;16(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-019-0227-1.

Fernandez-Fernandez B, Montoya-Ferrer A, Sanz AB, Sanchez-Niño MD, Izquierdo MC, Poveda J, et al. Tenofovir nephrotoxicity: 2011 update. AIDS Res Treat. 2011;2011:354908. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/354908.

World Health Organization. Medication safety in polypharmacy. 2019;1–63. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325454/WHO-UHC-SDS-2019.11-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Ware D, Palella FJ, Chew KW, Reuel Friedman M, D’Souza G, Ho K, et al. Prevalence and trends of polypharmacy among HIV-positive and -negative men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study from 2004 to 2016. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):1–14.

Gibbs A, Reddy T, Dunkle K, Jewkes R. HIV-Prevalence in South Africa by settlement type: a repeat population-based cross-sectional analysis of men and women. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230105.

Ssonko M, Stanaway F, Mayanja HK, et al. Polypharmacy among HIV positive older adults on anti-retroviral therapy attending an urban clinic in Uganda. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0817-0.

Moore HN, Mao L, Oramasionwu CU. Factors associated with polypharmacy and the prescription of multiple medications among persons living with HIV (PLWH) compared to non-PLWH. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2015;27(12):1443–8.

Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, Battegay M, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1130–9.

Justice AC, Gordon KS, Skanderson M, Edelman EJ, Akgün KM, Gibert CL, et al. Nonantiretroviral polypharmacy and adverse health outcomes among HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2018;32(6):739–49.

Wing EJ. International Journal of Infectious Diseases HIV and aging. 2016;53:61–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.10.004.

Siefried KJ, Mao L, Cysique LA, Rule J, Giles ML, Smith DE, et al. Concomitant medication polypharmacy, interactions and imperfect adherence are common in Australian adults on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2018;32:35–48.

Schlaeppi C, Vanobberghen F, Sikalengo G, Glass TR, Ndege RC, Foe G, et al. Prevalence and management of drug–drug interactions with antiretroviral treatment in 2069 people living with HIV in rural Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. HIV Med. 2020;21(1):53–63.

Dube MP. , Stein JH. AJ. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Dep Heal Hum Serv. 2021;40(Build 29393). Available from: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf

Courlet P, Livio F, Guidi M, Cavassini M, Battegay M, Stoeckle M, Buclin T, Alves Saldanha S, Csajka C, Marzolini C, Decosterd L; Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Polypharmacy, Drug-Drug Interactions, and Inappropriate Drugs: New Challenges in the Aging Population With HIV. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(12):ofz531. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz531.

DerSarkissian M, Bhak RH, Oglesby A, Priest J, Gao E, Macheca M, et al. Retrospective analysis of comorbidities and treatment burden among patients with HIV infection in a US Medicaid population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(5):781–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2020.1716706.

Greene M, Steinman MA, McNicholl IR, Valcour V. Polypharmacy, drug-drug interactions, and potentially inappropriate medications in older adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):447–53.

Greene M, Justice AC, Lampiris HW, Valcour V. Management of HIV in advanced age. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2013;309(13):1–20.

Krentz HB, Gill MJ. The impact of non-antiretroviral polypharmacy on the continuity of antiretroviral therapy (ART) among HIV patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(1):11–7.

Okoli C, de Los RP, Eremin A, Brough G, Young B, Short D. Relationship between polypharmacy and quality of life among people in 24 countries living with HIV. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E22.

Passos SMK, Souza LD de M. An evaluation of quality of life and its determinants among people living with HIV/AIDS from Southern Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2015;31(4):800–14.

Monteiro F, Canavarro MC, Pereira M. Factors associated with quality of life in middle- aged and older patients living with HIV with HIV. AIDS Care. 2016;0(0):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1146209

Smith JM, Flexner C. The challenge of polypharmacy in an aging population and implications for future antiretroviral therapy development. AIDS. 2017;31(January):S173–84.

Morillo-Verdugo R, Robustillo-Cortés MDLA, Martín LAK, De Sotomayor Paz MÁ, De León Naranjo FL, Almeida-González CV. Determination of a cutoff value for medication regimen complexity index to predict polypharmacy in HIV+ older patient. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2019;32(5):458–64.

Cañabate SF, Valín LO. Polypharmacy among HIV infected people aged 50 years or older. Colomb Med. 2019;50(3):142–52.

López-Centeno B, Badenes-Olmedo C, Mataix-Sanjuan Á, McAllister K, Bellón JM, Gibbons S, et al. Polypharmacy and Drug-Drug Interactions in People Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus in the Region of Madrid, Spain: A Population-Based Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(2):353–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz811.

Kong AM, Pozen A, Anastos K, Kelvin EA, Nash D. Non-HIV comorbid conditions and polypharmacy among people living with HIV age 65 or older compared with HIV-negative individuals age 65 or older in the United States: a retrospective claims-based analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(3):93–103.

Hovstadius B, Petersson G. Factors Leading to Excessive Polypharmacy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):159–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.001.

Marzolini C, Elzi L, Gibbons S, Weber R, Fux C, Furrer H, et al. Prevalence of comedications and effect of potential drug-drug interactions in the Swiss HIV cohort study. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(3):413–23.

Kara E, İnkaya AÇ, Hakli DA, Demirkan K, Ünal S. Polypharmacy and drug-related problems among people living with HIV/aids: a single-center experience. Turkish J Med Sci. 2019;49(1):222–9.

Mata-Marín JA, Martínez-Osio MH, Arroyo-Anduiza CI, Berrospe-Silva MDLÁ, Chaparro-Sánchez A, Cruz-Grajales I, et al. Comorbidities and polypharmacy among HIV-positive patients aged 50 years and over: A case-control study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4576-6.

Gleason LJ, Luque AE, Shah K. Polypharmacy in the HIV-infected older adult population. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:749–63. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S37738.

Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011453.

Osei-yeboah J, Owiredu WKBA, Norgbe GK, Lokpo SY, Obirikorang C, Allotey EA, et al. Quality of Life of People Living with HIV / AIDS in the Ho Municipality, Ghana : A Cross-Sectional Study. 2017;2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6806951.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere gratitude to all the staff in the Department of Internal Medicine of the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied sciences (MUHAS) and the Muhimbili National hospital (MNH) both in Upanga and Mloganzila campuses for their support during the entire period of execution of this work. Special thanks to the MNH Administration under the Executive Director Prof. Lawrance Museru. Thanks to Care and Treatment Clinic doctors, nurses and all other supporting staffs for their support during data collection. Thank you to Dr. Candida Moshiro, Prof. Sylvia Kaaya and Dr. Tumain Basil for the support in data analysis.

I am also grateful to all the clients who volunteered to participate in this study.

Funding

No funding was sought for this study. The costs were covered by the principle investigator who is the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I the main author Dr. Antimon Tibursi prepared the proposal under supervision of Dr. Grace A Shayo and Dr. Sabina F. Mugusi. Dr. Antimon T. Massawe did data collection and analysis. Final report was prepared by me Dr. Antimon T. Massawe and reviewed by Dr. Grace A Shayo and Dr. Sabina F Mugusi and provided their comments incorporated and then agreed on final report. The manuscript was prepared by Dr. Antimon T. Massawe and then reviewed by all authors and agreed together before submission.

Author’s information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) ethical committee (Reference number MUHAS-REC-08–2021-835 of 25th August 2021). Permissions to conduct the study in Muhimbili national hospital campuses were obtained from the respective campuses (Muhimbili National Hospital-Upanga campus and Mloganzila campus).

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants who participated in the study. Privacy and confidentiality was observed in all procedures by ensuring that the interviews were done in privacy (consultation rooms) and the questionnaires had no names instead they contained serial numbers for their identification. Patients who were to be contacted later for identification of their medications had their names matched to the questionnaire serial number and phone contact that were locked in an iron box and the key was kept safe with the primary investigator. Furthermore the data collection and handling of patients’ information was done only by medical personnel. All methods were carried out in accordance to relevant guidelines and regulations as stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Massawe, A.T., Shayo, G.A. & Mugusi, S.F. Polypharmacy and health related quality of life among older adults on antiretroviral therapy in a tertiary hospital in Tanzania: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 23, 179 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08150-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08150-x