Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a chronic infectious disease currently requiring lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART). People living with HIV (PLWH) face an increased risk of comorbidities associated with aging, chronic HIV, and the toxicity arising from long-term ART. A literature review was conducted to identify the most recent evidence documenting toxicities associated with long-term ART, particularly among aging PLWH. In general, PLWH are at a greater risk of developing fractures, osteoporosis, renal and metabolic disorders, central nervous system disorders, cardiovascular disease, and liver disease. There remains limited evidence describing the economic burden of long-term ART. Overall, an aging HIV population treated with long-term ART presents a scenario in which the clinical, humanistic, and economic burden for healthcare systems will demand thoughtful policy solutions that preserve access to treatment. Newer treatment regimens with fewer drugs may mitigate some of the cumulative toxicity burden of long-term ART.

Funding: ViiV Healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has led to substantial improvements in the life expectancy of patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which is now treated as a chronic disease requiring life-long ART treatment [1,2,3]. Current ART regimens are generally well tolerated with fewer associated severe adverse events (AEs) that are life-threatening or that lead to disability or permanent damage in the short term compared with older regimens; AE profiles that have been documented across all classes of ART are reported in Table 1 [4, 5]. There has been a decrease in the proportion of patients switching or discontinuing treatment, and fewer patients now discontinue ART compared with a decade ago [6]. This decrease can be attributed to factors including fewer AEs or intolerance with newer ART regimens as well as research showing that continuous use of ART is superior to episodic use [6, 7].

Advances in ART have also led to significant increases in survival among people living with HIV (PLWH) [8]; however, the corollary of a longer lifespan is that PLWH are now faced with an increased risk of developing comorbidities and chronic diseases associated with aging in addition to chronic HIV. Approximately 45% of PLWH are aged ≥ 50 years, and by 2020 an estimated 70% of Americans with HIV are projected to be in this age group [9, 10]. Furthermore, PLWH are now using ART over a much longer period of time, and the resulting potential cumulative toxicity that can emerge is not fully understood. Not only could such long-term toxicity lead to poor health status and a diminished quality of life but ART-related AEs that ultimately result in increases in morbidity and mortality risk may contribute significantly to healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with HIV treatment. Reducing the number of ART agents that PLWH require may have the potential to reduce cumulative toxicities as well as the economic burden associated with long-term treatment. Novel ART strategies, such as two-drug regimens, are currently being explored. While not all two-drug regimens studied to date have demonstrated efficacy and safety results indicative of an alternative to current regimens [11], certain regimens have been shown to provide non-inferior viral suppression along with reduced toxicity in virologically stable patients compared with three-drug regimens that are currently considered to be standard of care [12,13,14,15,16].

The objective of this review is to provide a synthesis of evidence documenting the toxicity implications arising from long-term ART use in high-income settings, particularly as it relates to an aging population of PLWH. The economic burden of AEs resulting from long-term ART use is also assessed.

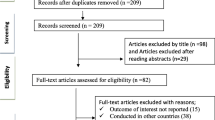

Methods

In this literature review, a combined approach of targeted searches of published literature for pre-specified topics of interest was supplemented with searches to identify additional major studies and clinical guidelines. Searches were conducted in MEDLINE (via PubMed) using keywords to identify studies reporting data on the AEs associated with long-term use of ART. Searches incorporated HIV-, AIDS-, treatment-, and economic-based terms (see supplementary material Table S1 and Table S2 for complete search strings). Identified studies were assessed by the authors and those relevant to the objectives of this review were included. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

For PLWH, long-term ART use has the potential to increase the underlying risk of conditions or diseases associated with both aging and chronic HIV infection. Nearly half of PLWH aged ≥ 50 years have at least one major medical comorbidity, and PLWH have more age-associated non-communicable comorbidities (AANCCs) than age-matched non-infected individuals [mean ± standard deviation (SD) number AANCCs: 1.3 ± 1.14 vs. 1.0 ± 0.95, respectively; P < 0.001] [17, 18]. Furthermore, the prevalence of comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and osteoporosis among PLWH significantly increases as PLWH age [19].

Chronic comorbidities also contribute to a greater pill burden, often resulting in additional complications [20, 21]. In an analysis of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, the proportion of PLWH who were taking at least four non-HIV co-medications was 5.2% among those aged 50–64 years compared with 14.2% for those aged ≥ 64 [19]. In a separate retrospective chart review of 89 older (≥ 60 years) PLWH, the median number of concomitant medications was 13 (range 9–17) compared with only 6 for their uninfected peers; of these 13 medications, only 4 were ART agents [22]. Several harmful effects of polypharmacy in older patients have been documented; these include drug–drug interactions (DDIs) between ART and therapies prescribed to manage non-HIV conditions, with Category D (consider therapy modification) DDIs reported in 70% of patients and Category X (avoid combination) DDIs reported in 11% of patients older than 60 years [22]. Additionally, a loss of treatment efficacy can often result from polypharmacy [23,24,25].

Common comorbidities that have known associations with long-term ART use and chronic HIV infection in older patients include fracture risk and osteoporosis, renal and metabolic disorders, central nervous system (CNS) disorders, cardiovascular disease, and liver disease.

Bone Disease

As PLWH age, they are at an increased risk for osteoporosis and fragility fractures, independent of long-term ART use [25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. In a cross-sectional study of 202 drug-naïve and drug-experienced PLWH, age was associated with the risk of fractures [odds ratio (OR) for each year = 1.18; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.03–1.25; P = 0.01]. Additionally, vertebral fracture was more prevalent among those aged 50–67 years compared with those aged 31–50 (32% vs. 13%; P = 0.008) [32]. A stronger association between HIV infection and major fractures in patients ≥ 59 years [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.11; 95% CI 1.05–4.22; P = 0.035] compared with patients < 59 (HR = 1.35; 95% CI 0.88–2.07; P = 0.17) has similarly been reported based on an analysis of medical records of Spanish PLWH (n = 2489) [30]. Additionally, the prevalence of fractures was higher among PLWH compared with HIV-uninfected peers for both men (P < 0.001) and women (P = 0.002) in a population-based study conducted at a large US healthcare system (n = 8525 PLWH; n = 2,208,792 HIV-uninfected), and the differences widened with increasing age [27].

The progression of bone disease among aging PLWH is further complicated by long-term toxicity concerns observed among patients treated with certain ART regimens. There is evidence that certain nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) are associated with declines in bone mineral density (BMD) and an increased risk of fractures in some studies; however, the issue remains controversial [33,34,35,36]. In an evaluation of HIV-infected patients in the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) Clinical Case Registry (n = 56,660), extended use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate was associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures (yearly HR = 1.08; P < 0.001), although this finding was no longer significant after multivariate adjustment for age, race, tobacco use, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and body mass index (HR = 1.06; P = 0.079) [35]. Recent results from the EuroSIDA study (n = 20,854) showed that ever (vs. never), current (vs. no current use), and cumulative tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use was associated with increased fracture risk among PLWH in a univariate analysis; however, there was no association for any other ART investigated [36]. After multivariate adjustment, the association between ever and current tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use remained significant [adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 1.40; 95% CI 1.15–1.70; P = 0.0008 and adjusted IRR = 1.25; 95% CI 1.05–1.49; P = 0.012, respectively], while cumulative tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use (per 5 years additional exposure) did not remain significant (adjusted IRR = 1.08; 95% CI 0.94–1.25; P = 0.027) [36]. Recently, tenofovir alafenamide has been used in place of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in ART regimens and has demonstrated smaller reductions in hip and lumbar spine BMD compared with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (P < 0.0001) [4, 37]. However, long-term data on potential toxicity associated with tenofovir alafenamide-containing regimens are lacking [4].

Renal and Metabolic Disorders

Older PLWH are at an increased risk of developing premature renal failure and DM compared with the general population [29]. A cross-sectional retrospective case–control study found that PLWH had a higher prevalence of both renal failure and DM compared with HIV-uninfected controls, especially among those aged > 60 years (24.26% vs. 0.49% and 38.97% vs. 15.93%, respectively; both P < 0.001) [29]. Among PLWH in the John Hopkins HIV Clinical Cohort who developed CKD (n = 284), the adjusted IRRs were 3.47 (95% CI 2.07–5.81; P < 0.001) and 1.45 (95% CI 1.01–2.09; P = 0.044) for those > 55 years and 45–55 years old, respectively, relative to PLWH < 45 years of age [38].

Toxicity resulting from long-term ART use that affects renal and metabolic health may further compound the overall disease burden in aging PLWH. Long-term use of ART has been linked to an increased risk of CKD and DM. In particular, an analysis of over 10,000 patients demonstrated a 33% increased risk of CKD for each additional year of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use (HR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.18–1.51; P < 0.0001) [39]. A similar analysis of 21,590 HIV-infected men found that the overall 5-year event rate of CKD in tenofovir disoproxil fumarate users compared with non-users was 7.7% versus 3.8%, respectively (overall adjusted HR = 2.0; 95% CI 1.8–2.2) [40]. Based on findings from the EuroSIDA study, higher rates of CKD have also been associated with a more frequent use of atazanavir (annual IRR = 1.21, P = 0.003) and lopinavir/ritonavir (annual IRR = 1.08; P = 0.030) [41]. Finally, in a prospective study of 1524 HIV-infected women with no evidence of DM, longer cumulative use of NRTIs was associated with an increased incidence of DM over the study period (October 2000 to March 2006) compared with no use of NRTIs (0–3 years NRTI use relative HR = 1.81; 95% CI 0.83–3.93; ≥ 3 years NRTI use relative HR = 2.64; 95% CI 1.11–6.32) [42].

Central Nervous System

Data on the effect of aging on CNS function among PLWH are mixed, and are complicated by potential synergistic effects of comorbid conditions including mental illness, the natural aging process, and HIV infection, each of which may contribute to decline in cognitive function [43,44,45,46]. Furthermore, while there are various screening tools available, there is a lack of clear consensus among care providers on how to diagnose and manage HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder [47, 48]. In a longitudinal case–control study including 54 PLWH and 30 HIV-uninfected individuals, the interaction of HIV and age significantly predicted longitudinal decline in verbal memory performance, suggesting that older age was associated with a greater decline in the HIV-positive group [43]. Additionally, in a prospective study of 146 PLWH with normal neurocognitive function at baseline, PLWH were nearly five times as likely to have a neurocognitive disorder after 14 months follow-up than patients without HIV; however, a logistic regression analysis found no effect of age (≤ 40 or ≥ 50 years) among PLWH on incident neurocognitive disorders over the same follow-up period (P = 0.410) [44]. In contrast, in a cross-sectional study (n = 392), older PLWH were at a higher risk of exhibiting cognitive impairment compared with younger PLWH (OR = 2.28; 95% CI 1.35–3.82; P = 0.002), although the extent to which the cognitive impairment is attributable solely to HIV or to an interaction between HIV infection and other age-related diseases is not fully understood [45].

The potentially increased risk for impaired CNS function among older PLWH is further complicated by evidence of an association between long-term ART and neurocognitive functioning. An analysis of neurocognitive functioning in patients from the CNS HIV Antiretroviral Therapy Effects Research cohort found that patients with long-term (median 17.9 months) use of efavirenz had worse speed of information processing (P = 0.04), verbal fluency (P = 0.03), and working memory (P = 0.03) relative to patients using ritonavir-boosted lopinavir [49]. Additionally, efavirenz has been shown to contribute to other serious long-term effects; a pre-specified retrospective analysis of four AIDS Clinical Trial Group studies reported a higher risk of suicidality (HR = 2.28; 95% CI 1.27–4.10; P = 0.006), defined as suicide ideation, attempted or completed suicide, or a numerically higher risk of attempted or completed suicide (HR = 2.58; 95% CI 0.94–7.06; P = 0.065) with efavirenz use compared with non-efavirenz regimens [50]. However, there is conflicting evidence to support this association; a retrospective analysis of data from the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System found that disproportionality scores for efavirenz were below the pre-determined threshold for a potential association for increased suicidality [51]. The AEs associated with efavirenz may be related to the dose of the drug; results from the ENCORE-1 trial showed that a dose of 400 mg efavirenz provided non-inferior efficacy and had fewer AEs than the standard dose of 600 mg efavirenz when combined with tenofovir plus emtricitabine in ART-naïve patients [52]. Rilpivirine has been studied as an alternative treatment to efavirenz in combination with two background NRTIs; this combination demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of neurological AEs compared with efavirenz in HIV-1 treatment-naïve patients enrolled in the ECHO and THRIVE trials [53, 54]. Improved neurological tolerability outcomes were also observed in a study of patients switching from an efavirenz-containing regimen to one containing rilpivirine [55].

In addition to efavirenz-related toxicity, a retrospective analysis evaluating patients with HIV who were treated with dolutegravir, raltegravir, and elvitegravir showed rates of neuropsychiatric AEs leading to discontinuation at 12/24 months of 5.6/6.7%, 0.7/1.5%, and 1.9/2.3%, respectively. In patients older than 60 years, the discontinuation rate due to neuropsychiatric AEs for dolutegravir was nearly three-fold higher compared with younger patients [56]. However, a recent analysis of five phase 3 clinical trials involving patients treated with dolutegravir-based regimens found that psychiatric symptoms were reported with low frequencies, were generally mild to moderate in intensity, and rarely necessitated dolutegravir discontinuation, similar to other commonly prescribed anchor drugs, including efavirenz, raltegravir, and darunavir [57].

Cardiovascular Disease

Rates of CVD mortality, acute MI risk, and ischemic stroke risk increase with age among PLWH, and the absolute risk for CVD is expected to increase in parallel with age [58,59,60,61]. A large US population-based cohort study showed that proportionate CVD mortality in PLWH increased from 1.95% in 1999 to 4.62% in 2013 (P < 0.0001) [59]. By comparison, the general population saw a decrease in proportionate CVD mortality over the same 15-year time period [59]. An analyses of male veterans (n = 76,835) found a higher risk for ischemic stroke among HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected veterans (adjusted HR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.01–1.36; P < 0.04) [60]. A separate analysis of 82,459 participants in the same cohort found that HIV-positive veterans had an increased risk of incident acute MI compared with uninfected veterans (adjusted HR = 1.48, 95% CI 1.27–1.72) [61]. In addition, the mean (95% CI) rate of acute MI events per 1000 person-years increased with age in HIV-infected veterans compared with uninfected veterans [2.0 (1.6–2.4) vs. 1.5 (1.3–1.7) for those aged 40–49 years; 3.9 (3.3–4.5) vs. 2.2 (1.9–2.5) for those aged 50–59; and 5.0 (3.8–6.7) vs. 3.3 (2.6–4.2) for those aged 60–69, respectively; P < 0.05 for all] [61]. However, it is difficult to discern to what extent the survival effect is leading to high rates of CVD in the aging HIV population.

The increased risk for CVD among older PLWH may be exacerbated by cumulative toxicity associated with ART. One study (n = 23,437) of PLWH showed that the incidence of MI over more than 6 years of follow-up was higher in patients treated with PIs than those not treated with PIs (6.01 per 1000 person-years vs. 1.53 per 1000 person years, respectively) [62]. After multivariate adjustment, the relative rate of MI per year of PI use was 1.16 (95% CI 1.10–1.23) [62]. The data regarding any association between abacavir and CVD risk are very mixed and the issue remains controversial [63,64,65,66,67,68,69]. Recently updated data from the D:A:D cohort (n = 49,717) found that current abacavir use was associated with a 98% increase in the rate of MI among PLWH compared with PLWH not currently on abacavir treatment (adjusted RR = 1.98, 95% CI 1.72–2.29) [65, 69].

Liver Disease

Liver-related morbidity and mortality are major concerns for PLWH, with liver disease accounting for approximately 13% of all deaths among PLWH [70]. As a person ages, the regenerative capacity of the liver declines. In addition, accelerated fibrogenesis has been observed in patients with HIV/HCV co-infection, although direct acting antivirals have now been shown to effectively treat and cure HCV infection in patients with HIV/HCV co-infection at rates similar to patients without HIV co-infection [71, 72]. However, there are limited data indicating that curing HCV in HIV/HCV co-infected patients reverses hepatic damage. Older age is also associated with increased risk of mitochondrial dysfunction, increased polypharmacy, worse prognosis of alcoholic liver disease, greater severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and an increased risk of liver cancer [73]. Although nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are frequently observed in PLWH, use of specific ART agents and duration of ART have not been established as risk factors [74]. NASH and NAFLD may be emerging comorbidities in this population based on the association between HIV and metabolic syndrome, which has a reported prevalence in patients with HIV from 11.2% up to 45.4% [75].

While the increased risk of liver disease among older PLWH is established, evidence describing the association between long-term ART use and liver-related toxicity is variable. In a study of 23,441 patients treated with NRTI-based ART, increased liver-related mortality has been observed with continuing use (annual relative risk = 1.11; 95% CI 1.02–1.12, P = 0.02) [76]. However, a large study of 22,910 patients without hepatitis virus co-infection over 114,478 person-years of follow-up (D.A.D. cohort) found that there were 12 liver-related deaths resulting in an incidence of 0.10/1000 person-years [77]. Seven deaths were due to severe alcohol use and five were due to established ART-related toxicity, the latter of which resulted in an ART-related mortality incidence of 0.04/1000 person-years. The increased risk of liver-related AEs, including liver fibrosis, with use of specific NRTIs such as didanosine is well known [78]. As a result of these known AEs, current treatment guidelines no longer recommend the use of didanosine [5, 79].

Economic Burden Associated with ART-Related Cumulative Toxicity

There is limited evidence describing the economic burden associated with cumulative toxicity that results from long-term ART use in older PLWH. Nevertheless, short-term toxicity-related costs among PLWH who are treated with ART have been documented, and there is an expectation that healthcare costs will increase commensurately as PLWH age. In a retrospective Medicaid claims analysis of PLWH treated with ATV or darunavir (n = 2426), the mean ± SD per-patient per-month costs of all medically attended AEs were US$3879 ± $6635 and $5354 ± $8127, respectively [80]. In another US claims analysis of PLWH treated with NNRTIs (n = 2548), mean total healthcare costs (12 months) were estimated to be $27,299 ± $37,170, and annual AE-associated costs were $608 ± $3897 [81]. Costs varied from $586 for lipid disorders to $4434 for nausea/vomiting. A retrospective US case–control study found that for patients who had initiated ART within the last 12 months, the median difference (episode with event of interest vs. without event of interest) in total all-cause healthcare costs was $3310 for managing diabetes/insulin resistance, $2792 for lipid disorders, $1389 for a renal disorder event, $390 for rash, $357 for a somnolence/sleep event, and $212 for a hepatic disorder event [82]. Aging in the population of PLWH is likely to add to the cost of HIV management; between 1999 and 2011, the proportion of older PLWH increased from 9.6 to 25.4%, and proportional costs increased from 25 to 31% [83].

Potential for New Therapies to Improve Long-Term Outcomes

Among PLWH, shifting from targeting an acute infection to managing a chronic disease requires new approaches to treatment and drug regimens that ultimately achieve viral suppression while minimizing cumulative toxicities. While continued improvements in ART cannot fully address issues related to chronic inflammation and other comorbidities associated with HIV and long-term ART in aging patients, such regimens have the potential to improve patient adherence, reduce pill burden, and ultimately lower the economic impact of cumulative toxicities. Novel approaches to treatment in certain patient populations include ART regimens taken 4 days per week compared with continuous ART 7 days per week (QUATUOR trial) [84], the use of long-acting injectable formulations [85], and two-drug regimens [13, 16, 85,86,87].

Assuming viral loads can be controlled with fewer drugs in a treatment regimen, the risk of toxicity associated with long-term ART may be lowered. Recent head-to-head studies of two-drug regimens comparing either atazanavir–ritonavir plus lamivudine or rilpivirine plus boosted darunavir to currently recommended three- or four-drug ART in virologically stable patients have shown non-inferior efficacy and favorable AE profiles for two-drug regimens [13, 16]. Studies investigating treatment switching from three- or four-drug regimens to two- or one-drug regimens in virologically stable patients have also demonstrated non-inferior efficacy and comparable or a more favorable AE profile associated with regimens that include fewer drugs [12, 14, 15, 85,86,87]; several switch studies are ongoing [88,89,90,91]. These recent head-to-head trials and switch studies are generally limited to a duration of 1 year or less, and may therefore underestimate the benefits of initiating or switching to simplified regimens that potentially have fewer cumulative long-term toxicities.

Limitations

The findings reported in this literature review are subject to several limitations. The review was non-systematic and thus did not identify literature from a broad set of databases or undergo dual-reviewer study screening and evaluation. Additionally, while we attempted to include impactful and meaningful studies, we did not conduct a formal quality assessment and thus the quality of data reported may vary. Furthermore, not all included studies were case–control studies and caution should be used when interpreting findings of excess comorbidities among PLWH. Indeed, while not the focus of this review, lifestyle factors that affect patients without HIV as well as PLWH and that lead to age-related comorbidities may also complicate treatment outcomes among PLWH. Finally, the apparent lack of literature focusing on the economic burden of long-term ART toxicities may be a result of the non-systematic nature of the review, but may also highlight an important evidence gap and area of potential future research.

Conclusion

Potential cumulative toxicity remains a concern as more patients experience long-term treatment and are at greater risk for chronic diseases associated with aging, despite recent advances in ART that have significantly increased the life expectancy of PLWH and offer better safety profiles. Newer treatment regimens with fewer drugs may help mitigate the clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of cumulative toxicity that emerges because of long-term use of ART. Together, aging and long-term treatment of HIV as a chronic disease imply the risk of greater economic burden for healthcare systems, which will demand thoughtful policy solutions that preserve access to innovative ART.

References

May MT, Gompels M, Delpech V, Porter K, Orkin C, Kegg S, et al. Impact on life expectancy of HIV-1 positive individuals of CD4+ cell count and viral load response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2014;28(8):1193–202. https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0000000000000243.

Marcus JL, Chao CR, Leyden WA, Xu L, Quesenberry CP Jr, Klein DB, et al. Narrowing the gap in life expectancy between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals with access to care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(1):39–46.

Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1525–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61809-7.

European AIDS Clinical Society. Guidelines version 9.0. October 2017. http://www.eacsociety.org/files/guidelines_9.0-english.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2018.

Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. March 27, 2018. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2018.

Cicconi P, Cozzi-Lepri A, Castagna A, Trecarichi E, Antinori A, Gatti F, et al. Insights into reasons for discontinuation according to year of starting first regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a cohort of antiretroviral-naïve patients. HIV Med. 2010;11(2):104–13.

El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, Gordin F, Abrams D, Arduino RC, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(22):2283–96. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa062360.

The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(8):e349–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3018(17)30066-8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2016; vol 28. November 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed 1 May 2018.

Aitcheson P, Brennan-Ing M, Espinoza R, Pacheco B, Tax A, Tietz D. Eight policy recommendations for improving the health and wellness of older adults with HIV. 2014. http://www.diverseelders.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/DEC-HIV-and-Aging-Policy-Report_web.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2018.

van Lunzen J, Pozniak A, Gatell JM, Antinori A, Klauck I, Serrano O, et al. Brief report: switch to ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus raltegravir in virologically suppressed patients with HIV-1 infection: a randomized pilot study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(5):538–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000000904.

Llibre JM, Hung CC, Brinson C, Castelli F, Girard PM, Kahl LP, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of dolutegravir-rilpivirine for the maintenance of virological suppression in adults with HIV-1: phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority SWORD-1 and SWORD-2 studies. Lancet. 2018;391(10123):839–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33095-7.

Maggiolo F, Di Filippo E, Valenti D, Ortega PS, Callegaro A. NRTI sparing therapy in virologically controlled HIV-1 infected subjects: results of a controlled, randomized trial (Probe). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(1):46–51.

Mondi A, Fabbiani M, Ciccarelli N, Colafigli M, D’Avino A, Borghetti A, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment simplification to atazanavir/ritonavir + lamivudine in HIV-infected patients with virological suppression: 144 week follow-up of the AtLaS pilot study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(6):1843–9.

Perez-Molina J, Rubio R, Rivero A, Pasquau J, Suárez-Lozano I, Riera M, et al. Simplification to dual therapy (atazanavir/ritonavir + lamivudine) versus standard triple therapy [atazanavir/ritonavir + two nucleos (t) ides] in virologically stable patients on antiretroviral therapy: 96 week results from an open-label, non-inferiority, randomized clinical trial (SALT study). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(1):246–53.

Perez-Molina JA, Rubio R, Rivero A, Pasquau J, Suárez-Lozano I, Riera M, et al. Dual treatment with atazanavir–ritonavir plus lamivudine versus triple treatment with atazanavir–ritonavir plus two nucleos (t) ides in virologically stable patients with HIV-1 (SALT): 48 week results from a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(7):775–84.

Rodriguez-Penney AT, Iudicello JE, Riggs PK, Doyle K, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, et al. Co-morbidities in persons infected with HIV: increased burden with older age and negative effects on health-related quality of life. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(1):5–16.

Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG, Kootstra NA, van der Valk M, Geerlings SE et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals: the AGEhIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(12):1787–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu701.

Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1130–9.

Krentz HB, Cosman I, Lee K. JM M, MJ G. Pill burden in HIV infection: 20 years of experience. Antiviral Ther. 2012;17(5):833–40. https://doi.org/10.3851/imp2076.

Zhou S, Martin K, Corbett A, Napravnik S, Eron J, Zhu Y, et al. Total daily pill burden in HIV-infected patients in the southern United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(6):311–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2014.0010.

Greene M, Steinman MA, McNicholl IR, Valcour V. Polypharmacy, drug–drug interactions, and potentially inappropriate medications in older adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):447–53.

Holtzman C, Armon C, Tedaldi E, et al, editors. Polypharmacy and risk of antiretroviral (ARV) drug interactions among the aging HIV-positive population: findings from the HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS). XIX International AIDS Conference; 2012; Washington, DC.

Jourjy J, Dahl K, Huesgen E. Antiretroviral treatment efficacy and safety in older HIV-infected adults. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(12):1140–51.

Smit M, Brinkman K, Geerlings S, Smit C, Thyagarajan K, van Sighem A, et al. Future challenges for clinical care of an ageing population infected with HIV: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(7):810–8.

Sharma A, Shi Q, Hoover DR, Anastos K, Tien PC, Young MA, et al. Increased fracture incidence in middle-aged HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women: updated results from the women’s interagency HIV study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(1):54–61.

Triant VA, Brown TT, Lee H, Grinspoon SK. Fracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected versus non-HIV-infected patients in a large US healthcare system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(9):3499–504.

Shiau S, Broun EC, Arpadi SM, Yin MT. Incident fractures in HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England). 2013;27(12):1949.

Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, Menozzi M, Carli F, Garlassi E, et al. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1120–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir627.

Güerri-Fernandez R, Vestergaard P, Carbonell C, Knobel H, Avilés FF, Castro AS, et al. HIV infection is strongly associated with hip fracture risk, independently of age, gender, and comorbidities: a population-based cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(6):1259–63.

Yin MT, Lu D, Cremers S, Tien PC, Cohen MH, Shi Q, et al. Short term bone loss in HIV infected premenopausal women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(2):202.

Borderi M, Calza L, Colangeli V, Vanino E, Viale P, Gibellini D, et al. Prevalence of sub-clinical vertebral fractures in HIV-infected patients. New Microbiol. 2014;37(1):25–32.

McComsey GA, Kitch D, Daar ES, Tierney C, Jahed NC, Tebas P, et al. Bone mineral density and fractures in antiretroviral-naive persons randomized to receive abacavir-lamivudine or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine along with efavirenz or atazanavir-ritonavir: aIDS Clinical Trials Group A5224 s, a substudy of ACTG A5202. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(12):1791–801.

Huang JS, Hughes MD, Riddler SA, Haubrich RH. Team ACTGAS. Bone mineral density effects of randomized regimen and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor selection from ACTG A5142. HIV Clin Trials. 2014;14(5):224–34.

Bedimo R, Maalouf NM, Zhang S, Drechsler H, Tebas P. Osteoporotic fracture risk associated with cumulative exposure to tenofovir and other antiretroviral agents. AIDS. 2012;26(7):825–31.

Borges AH, Hoy J, Florence E, Sedlacek D, Stellbrink HJ, Uzdaviniene V, et al. Antiretrovirals, fractures, and osteonecrosis in a large international HIV cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(10):1413–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix167.

Sax PE, Wohl D, Yin MT, Post F, DeJesus E, Saag M, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet. 2015;385(9987):2606–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60616-x.

Lucas GM, Lau B, Atta MG, Fine DM, Keruly J, Moore RD. Chronic kidney disease incidence, and progression to end-stage renal disease, in HIV-infected individuals: a tale of two races. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(11):1548–57.

Scherzer R, Estrella M, Yongmei L, Deeks SG, Grunfeld C, Shlipak MG. Association of tenofovir exposure with kidney disease risk in HIV infection. AIDS (London, England). 2012;26(7):867.

Scherzer R, Gandhi M, Estrella MM, Tien PC, Deeks SG, Grunfeld C, et al. A chronic kidney disease risk score to determine tenofovir safety in a prospective cohort of HIV-positive male veterans. AIDS. 2014;28(9):1289–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0000000000000258.

Mocroft A, Kirk O, Reiss P, De Wit S, Sedlacek D, Beniowski M, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate, chronic kidney disease and antiretroviral drug use in HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2010;24(11):1667–78.

Tien PC, Schneider MF, Cole SR, Levine AM, Cohen M, DeHovitz J, et al. Antiretroviral therapy exposure and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the Women’s interagency HIV study. AIDS. 2007;21(13):1739–45.

Seider TR, Luo X, Gongvatana A, Devlin KN, de la Monte SM, Chasman JD, et al. Verbal memory declines more rapidly with age in HIV infected versus uninfected adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2014;36(4):356–67.

Sheppard DP, Woods SP, Bondi MW, Gilbert PE, Massman PJ, Doyle KL. Does older age confer an increased risk of incident neurocognitive disorders among persons living with HIV disease? Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;29(5):656–77.

Pinheiro CAT, Souza LDdM, Motta JVdS, Kelbert EF, Martins CdSR, Souza MSd, et al. Aging, neurocognitive impairment and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Braz J Infect Dis. 2016;20(6):599–604.

Havlik RJ, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Comorbidities and depression in older adults with HIV. Sex Health. 2011;8(4):551–9. https://doi.org/10.1071/sh11017.

Mind Exchange Working Group. Assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder: a consensus report of the mind exchange program. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(7):1004–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis975.

Kamminga J, Cysique LA, Lu G, Batchelor J, Brew BJ. Validity of cognitive screens for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder: a systematic review and an informed screen selection guide. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(4):342–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-013-0176-6.

Ma Q, Vaida F, Wong J, Sanders CA, Y-t Kao, Croteau D, et al. Long-term efavirenz use is associated with worse neurocognitive functioning in HIV-infected patients. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(2):170–8.

Mollan KR, Smurzynski M, Eron JJ, Daar ES, Campbell TB, Sax PE, et al. Association between efavirenz as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection and increased risk for suicidal ideation or attempted or completed suicide: an analysis of trial data. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(1):1–10.

Napoli AA, Wood JJ, Coumbis JJ, Soitkar AM, Seekins DW, Tilson HH. No evident association between efavirenz use and suicidality was identified from a disproportionality analysis using the FAERS database. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):19214.

ENCORE1 Study Group. Efficacy of 400 mg efavirenz versus standard 600 mg dose in HIV-infected, antiretroviral-naive adults (ENCORE1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1474–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62187-x.

Mills AM, Antinori A, Clotet B, Fourie J, Herrera G, Hicks C, et al. Neurological and psychiatric tolerability of rilpivirine (TMC278) vs. efavirenz in treatment-naive, HIV-1-infected patients at 48 weeks. HIV Med. 2013;14(7):391–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12012.

Molina JM, Clumeck N, Orkin C, Rimsky LT, Vanveggel S, Stevens M. Week 96 analysis of rilpivirine or efavirenz in HIV-1-infected patients with baseline viral load </= 100 000 copies/mL in the pooled ECHO and THRIVE phase 3, randomized, double-blind trials. HIV Med. 2014;15(1):57–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12071.

Cazanave C, Reigadas S, Mazubert C, Bellecave P, Hessamfar M, Le Marec F, et al. Switch to rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir single-tablet regimen of human immunodeficiency virus-1 rna-suppressed patients, agence nationale de recherches sur le sida et Les hepatites virales CO3 aquitaine cohort, 2012–2014. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2(1):ofv018. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofv018.

Hoffmann C, Welz T, Sabranski M, Kolb M, Wolf E, Stellbrink HJ, et al. Higher rates of neuropsychiatric adverse events leading to dolutegravir discontinuation in women and older patients. HIV Med. 2017;18(1):56–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12468.

Fettiplace A, Stainsby C, Winston A, Givens N, Puccini S, Vannappagari V, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients receiving dolutegravir. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(4):423–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000001269.

Martin-Iguacel R, Llibre JM, Friis-Moller N. Risk of cardiovascular disease in an aging HIV population: where are we now? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(4):375–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-015-0284-6.

Feinstein MJ, Bahiru E, Achenbach C, Longenecker CT, Hsue P, So-Armah K, et al. Patterns of cardiovascular mortality for HIV-infected adults in the United States: 1999 to 2013. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(2):214–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.030.

Sico JJ, Chang CC, So-Armah K, Justice AC, Hylek E, Skanderson M, et al. HIV status and the risk of ischemic stroke among men. Neurology. 2015;84(19):1933–40. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000001560.

Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, Skanderson M, Lowy E, Kraemer KL, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):614–22. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728.

Friis-Møller N, Sabin CA, Weber R, d’Arminio Monforte A, El-Sadr WM, Reiss P, et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(21):1993–2003. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa030218.

Cruciani M, Zanichelli V, Serpelloni G, Bosco O, Malena M, Mazzi R, et al. Abacavir use and cardiovascular disease events: a meta-analysis of published and unpublished data. AIDS (London, England). 2011;25(16):1993–2004. https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0b013e328349c6ee.

Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, Gilquin J, Partisani M, Simon A, et al. Impact of individual antiretroviral drugs on the risk of myocardial infarction in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: a case-control study nested within the French Hospital Database on HIV ANRS cohort CO4. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(14):1228–38. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.197.

Sabin CA, Reiss P, Ryom L, Phillips AN, Weber R, Law M, et al. Is there continued evidence for an association between abacavir usage and myocardial infarction risk in individuals with HIV? A cohort collaboration. BMC Med. 2016;14:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0588-4.

Santos JR, Saumoy M, Curran A, Bravo I, Llibre JM, Navarro J, et al. The lipid-lowering effect of tenofovir/emtricitabine: a randomized, crossover, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):403–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ296.

Ding X, Andraca-Carrera E, Cooper C, Miele P, Kornegay C, Soukup M, et al. No association of abacavir use with myocardial infarction: findings of an FDA meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(4):441–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826f993c.

Thomas GP, Li X, Post WS, Jacobson LP, Witt MD, Brown TT, et al. Associations between antiretroviral use and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. AIDS. 2016;30(16):2477–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0000000000001220.

Sabin CA, Worm SW, Weber R, Reiss P, El-Sadr W, Dabis F, et al. Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the D:A:D study: a multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet. 2008;371(9622):1417–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60423-7.

Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, Morlat P, Pradier C, Reiss P, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet. 2014;384(9939):241–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60604-8.

Chan AW, Patel YA, Choi S. Aging of the liver: what this means for patients with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016;13(6):309–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-016-0332-x.

Wyles DL, Sulkowski MS, Dieterich D. Management of hepatitis C/HIV coinfection in the era of highly effective hepatitis C virus direct-acting antiviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(Suppl 1):S3–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw219.

Falade-Nwulia O, Thio CL. Liver disease, HIV and aging. Sex Health. 2011;8(4):512–20.

Morse CG, McLaughlin M, Matthews L, Proschan M, Thomas F, Gharib AM, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatic fibrosis in HIV-1-monoinfected adults with elevated aminotransferase levels on antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(10):1569–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ101.

Paula AA, Falcao MC, Pacheco AG. Metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected individuals: underlying mechanisms and epidemiological aspects. AIDS Res Ther. 2013;10(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-6405-10-32.

Weber R, Sabin CA, Friis-Moller N, Reiss P, El-Sadr WM, Kirk O, et al. Liver-related deaths in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: the D:A:D study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1632–41.

Kovari H, Sabin CA, Ledergerber B, Ryom L, Worm SW, Smith C, et al. Antiretroviral drug-related liver mortality among HIV-positive persons in the absence of hepatitis B or C virus coinfection: the data collection on adverse events of anti-HIV drugs study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):870–9.

Kooij KW, Wit FW, Van Zoest RA, Schouten J, Kootstra NA, Van Vugt M, et al. Liver fibrosis in HIV-infected individuals on long-term antiretroviral therapy: associated with immune activation, immunodeficiency and prior use of didanosine. AIDS. 2016;30(11):1771–80.

Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, del Rio C, Eron JJ, Gallant JE, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2016 recommendations of the international antiviral society—USA Panel. JAMA. 2016;316(2):191–210.

Johnston SS, Juday T, Esker S, Espindle D, Chu BC, Hebden T, et al. Comparative incidence and health care costs of medically attended adverse effects among US medicaid HIV patients on atazanavir- or darunavir-based antiretroviral therapy. Value Health. 2013;16(2):418–25.

Simpson KN, Chen SY, Wu AW, Boulanger L, Chambers R, Nedrow K, et al. Costs of adverse events among patients with HIV infection treated with nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. HIV Med. 2014;15(8):488–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12145.

Dekoven M, Makin C, Slaff S, Marcus M, Maiese EM. Economic burden of HIV antiretroviral therapy adverse events in the United States. J Int Assoc Phys AIDS Care. 2016;15(1):66–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325957415594883.

Krentz H, Gill M. Increased costs of HIV care associated with aging in an HIV-infected population. HIV Med. 2015;16(1):38–47.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Antiretroviral treatment taken 4 days per week versus continuous therapy 7/7 days per week in HIV-1 infected patients (QUATUOR). 2018. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT03256422. Accessed April 13, 2018.

Margolis DA, Gonzalez-Garcia J, Stellbrink H-J, Eron JJ, Yazdanpanah Y, Podzamczer D, et al. Long-acting intramuscular cabotegravir and rilpivirine in adults with HIV-1 infection (LATTE-2): 96-week results of a randomised, open-label, phase 2b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10101):1499–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31917-7.

Di Giambenedetto S, Fabbiani M, Quiros Roldan E, Latini A, D’Ettorre G, Antinori A, et al. Treatment simplification to atazanavir/ritonavir + lamivudine versus maintenance of atazanavir/ritonavir + two NRTIs in virologically suppressed HIV-1-infected patients: 48 week results from a randomized trial (ATLAS-M). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(4):1163–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw557.

Paton NI, Stöhr W, Arenas-Pinto A, Fisher M, Williams I, Johnson M, et al. Protease inhibitor monotherapy for long-term management of HIV infection: a randomised, controlled, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(10):e417–26.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of long-acting intramuscular cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance of virologic suppression following switch from an integrase inhibitor in HIV-1 infected therapy naive participants. 2017. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02938520. Accessed April 13, 2018.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of long-acting intramuscular cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance of virologic suppression following switch from an integrase inhibitor in HIV-1 infected therapy naive participants. 2018. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02951052. Accessed April 16, 2018.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Efficacy, safety and tolerability study of long-acting cabotegravir plus long-acting rilpivirine (CAB LA + RPV LA) in human-immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) infected adults. 2018. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03299049. Accessed April 16, 2018.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Dual therapy with boosted darunavir + dolutegravir (Dualis). 2018. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02486133. Accessed April 16, 2018.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were funded by ViiV Healthcare, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors thank Marcia Reinhart, DPhil, of Analysis Group Inc., for providing medical writing and editorial support; Analysis Group received consultancy fees from ViiV Healthcare for this support.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Miranda Murray is an employee of ViiV Healthcare. Yogesh Punekar is an employee of ViiV Healthcare. Annemiek de Ruiter was affiliated with Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, during the conduct of this review. Annemiek de Ruiter is now an employee of ViiV Healthcare, Brentford, Middlesex, UK. Corklin Steinhart is an employee of ViiV Healthcare. Anita Chawla is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. Cody Patton is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. Christina Wang was an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., during the conduct of this review. Christina Wang is now a medical student at University of California, San Francisco, California, USA. Analysis Group, Inc., has received consultancy fees from ViiV Healthcare to carry out this research.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6170426.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chawla, A., Wang, C., Patton, C. et al. A Review of Long-Term Toxicity of Antiretroviral Treatment Regimens and Implications for an Aging Population. Infect Dis Ther 7, 183–195 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-018-0201-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-018-0201-6