Abstract

Background

Several anti-cytokine therapies were tested in the randomized trials in hospitalized patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (COVID-19). Previously, dexamethasone demonstrated a reduction of case-fatality rate in hospitalized patients with respiratory failure. In this matched control study we compared dexamethasone to a Janus kinase inhibitor, ruxolitinib.

Methods

The matched cohort study included 146 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and oxygen support requirement. The control group was selected 1:1 from 1355 dexamethasone-treated patients and was matched by main clinical and laboratory parameters predicting survival. Recruitment period was April 7, 2020 through September 9, 2020.

Results

Ruxolitinib treatment in the general cohort of patients was associated with case-fatality rate similar to dexamethasone treatment: 9.6% (95% CI [4.6–14.6%]) vs 13.0% (95% CI [7.5–18.5%]) respectively (p = 0.35, OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.31–1.57]). Median time to discharge without oxygen support requirement was also not different between these groups: 13 vs. 11 days (p = 0.13). Subgroup analysis without adjustment for multiple comparisons demonstrated a reduced case-fatality rate in ruxolitnib-treated patients with a high fever (≥ 38.5 °C) (OR 0.33, 95% CI [0.11–1.00]). Except higher incidence of grade 1 thrombocytopenia (37% vs 23%, p = 0.042), ruxolitinib therapy was associated with a better safety profile due to a reduced rate of severe cardiovascular adverse events (6.8% vs 15%, p = 0.025). For 32 patients from ruxolitinib group (21.9%) with ongoing progression of respiratory failure after 72 h of treatment, additional anti-cytokine therapy was prescribed (8–16 mg dexamethasone).

Conclusions

Ruxolitinib may be an alternative initial anti-cytokine therapy with comparable effectiveness in patients with potential risks of steroid administration. Patients with a high fever (≥ 38.5 °C) at admission may potentially benefit from ruxolitinib administration.

Trial registration The Ruxolitinib Managed Access Program (MAP) for Patients Diagnosed With Severe/Very Severe COVID-19 Illness NCT04337359, CINC424A2001M, registered April, 7, 2020. First participant was recruited after registration date

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is now established that excessive production of cytokines is an important part of pathogenesis during severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) [1, 2]. Usually patients present with an elevation of multiple cytokines [3, 4]. Clinical consequence of increased cytokine production is the development of hyperinflammatory syndrome (HIS), also called cytokine-release syndrome, or macrophage-activation syndrome, or secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Symptoms of HIS usually include a high fever (≥ 38.5 °C), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), encephalopathy, abnormal liver function tests, acute kidney injury, lymphopenia, low platelet count [2, 5].

Based on these observations of HIS, various types of anti-cytokine therapies were evaluated in COVID-19 patients, including anti-interleukin-6 (IL-6) [6], anti-interleukin-1 (IL-1) [7] and anti-granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [8]. Despite a faster resolution of symptoms, which was reported in these studies so far, only dexamethasone [9] and baricitinib [10], a Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and 2 inhibitor, demonstrated improved survival in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 compared to the standard of care.

Another JAK 1/2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, also demonstrated effective anti-cytokine properties in myelofibrosis [11], graft-versus host disease (GVHD) [12] and secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [13]. Also, ruxolitinib was reported to improve COVID-19 clinical course in several small patient series [14, 15]. Recently the press release indicated that randomized RUXCOVID study did not meet its primary endpoint of reduced cumulative incidence of death, mechanical ventilation, or ICU care compared to the standard of care [16]. Since the ‘standard’ of care for COVID-19 is constantly changing and, unlike the early studies, now a majority of severe patients do receive some form of anti-cytokine therapy, we compared ruxolitinib with the most common immunosuppressive treatment, dexamethasone, in the multicenter matched cohort study.

Objective

Estimation of ruxolitinib effectiveness and safety in comparison with conventional glucocorticosteroid therapy in COVID-19 patients.

Methods

Patients

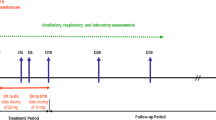

The study was conducted in four large specialized hospitals for COVID-19 infection in Saint-Petersburg and Moscow. Recruitment period was April 7, 2020 through September 9, 2020. The active treatment arm included 146 patients (Fig. 1) from the Ruxolitinib Managed Access Program (MAP) for Patients Diagnosed With Severe/Very Severe COVID-19 Illness (www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT04337359, CINC424A2001M), recruited after the date of the trial registration. The inclusion criteria in this analysis were PCR-confirmed case of COVID-19 infection, respiratory support and 5–6 score on the Ordinal scale [17, 18]. Patients with scores 4 and less were excluded because these patients generally receive outpatient care in the Russian Federation and the sample of hospitalized patients is not representative of this population. Patients with score 7 and higher were excluded because there is limited data on pharmacokinetics of ruxolitinib after administration of crushed pills via gastric tube. The only exclusion criterion in the analysis was a terminal oncological illness on a palliative care. All consecutive patients meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the analysis.

COVID-19 infection was confirmed by both the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab with RealBest RNA SARS-CoV-2 test kit for real time PCR (Vector-Best, Novosibirsk, Russian Federation). Patients were followed up until death or discharge. Local ethical committees approved the participation of patients in the Managed Access Program and all patients signed informed consent for the treatment. Ruxolitinib was administered in doses 5–10 mg bid. Median dose was 0.125 was mg/kg/day. Dose distribution per kilogram of patient weight is presented in Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Ruxolitinib was administered until oxygen support withdrawal. Computer tomography (CT) severity grade was assessed using the recommendations by the Russian Ministry of Health. In brief, the grading system is based on the percentage of affected lung tissue: grade 1 (< 25%), grade 2 (25–50%), grade 3 (51–75%), grade 4 (> 75%) [17].

The control group was selected from 1355 simultaneously hospitalized patients (Fig. 1) receiving 16–24 mg of dexamethasone daily due to respiratory failure (WHO score > 4). The duration of dexamethasone therapy was 5–10 days based on the symptoms severity.

Data was downloaded from the local health information system and manually checked for potential outliers. There were no missing values in baseline data. For the restoration of unknown values between two sequential tests, the “last observation carried forward” procedure (LOCF) was applied.

Outcome measures, group matching and statistical analysis

The following major clinical and laboratory disease features were used for selection of patients for the control group: age, gender, body mass index (BMI), SpO2 without oxygen support, C-reactive protein (CRP), pre-existing diabetes, absolute lymphocyte count and the day of illness. Additional parameters assessed during matching were body temperature, serum ferritin, serum creatinine, serum glucose level, white blood cell (WBC) count, potassium, sodium, hemoglobin, neutrophil count, monocyte count, platelet count, pre-existing HIV, cardiovascular, respiratory, liver disorders, tuberculosis in the patient’s history and oncological disease requiring active treatment. CT grade was not included in the matching parameters because it was not yet validated for patient case-fatality. Only pre-treatment laboratory measures were used for matching. The propensity score matching was based on all of these parameters and selection of the control group with 1:1 ratio. The balance of covariates before and after matching is given in Additional file 1: Fig. S2. Contingency table for case-fatality rate before and after matching is available in Additional file 1: Table S1.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for selection of outcomes were used to define the outcome of the study [19]. Cumulative incidences of death and discharge as competing risks were selected as the primary outcome of the study based on the following considerations: (1) the universal healthcare system in the Russian Federation excludes discharges for economic reasons, which is the main concern about discharge endpoint; (2) we were not limited in the follow up time of intubated or discharged patients, so either one or another outcome did occur within the scope of the study; (3) time to PCR-negativity was not an appropriate endpoint in this study because some asymptomatic patients were discharged before PCR-negativity. The differences in clinical measures, laboratory parameters and toxicity between study groups were assessed Chi-square and Mann–Whitney tests according to the data type. Cumulative incidence analysis and Gray test were used to compare case-fatality rates and discharge rates between dexamethasone and ruxolitinib arms.

Also a subgroup analysis based on binary thresholding of various variables was performed. In it odds ratios derived from 2 × 2 contingency tables with death as an outcome were estimated. CRP threshold for subgroup analysis was selected from the set of dexamethasone patients not included in the main analysis. In this group of patients receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis was performed targeting highest average sensitivity and specificity for in-hospital case-fatality rate. The resulting threshold level was approximately 100 mg/L (Additional file 1: Fig. S4). All analyses were performed using R software, version 4.0.4. The packages used for the analysis are listed in Additional file 1: Table S4.

For sensitivity analysis we conducted a clustering of ruxolitinib group based on the selected matching variables. The survival in the three selected clusters was 85% vs 98% vs 87%, p = 0.0087 (Additional file 1: Fig. S4, Table S2). Thus, the algorithm effectively selected the cluster 2 of patients with a low risk of death. After that for each cluster a matching was performed for a control group selection and a comparison of case fatality rates (Additional file 1: Fig. S5, Table S3).

Results

Analyzed groups of patients with ruxolitinib (N = 146) and dexamethasone (N = 146) treatments were well matched in their clinical and laboratory parameters (Table 1). All patients included in the study received intermediate doses of anticoagulant medications (low-molecular-weight heparin). In the ruxolitinib group, 94% of patients were treated with antibiotic therapy, in the control group—88%. For 32 patients from ruxolitinib group (21.9%) with ongoing progression of respiratory failure after 72 h of treatment, additional anti-cytokine therapy was prescribed (8–16 mg dexamethasone).

Cumulative incidence of death from COVID-19 was 9.6% in the ruxolitinib group (N = 14) and 13.0% in the dexamethasone group (N = 19), p = 0.35, OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.31–1.57] (see Fig. 2). Absolute risk difference—3.4% (95% CI [− 3.8, 10.7%]). Median time to discharge was 13 vs 11 days for these groups, respectively (p = 0.13). The subgroup analysis of case-fatality rate without adjustment for multiple comparisons demonstrated that dexamethasone was not superior to ruxolitinib in any of the subgroups tested. However, ruxolitinib administration was associated with a borderline case-fatality reduction in patients with a high persistent fever (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.11–1.00). Also, surprisingly, improved survival was observed not in patients with cardiovascular disease who were expected to tolerate steroids worse than ruxolitinib, but in patients without cardiovascular disease (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.06–0.88, Fig. 3). None of the other complete blood count parameters (Additional file 1: Fig. S6), biochemistry parameters (Additional file 1: Fig. S7), demographic parameters (Additional file 1: Fig. S8) or CT stage (Additional file 1: Table S5) were predisposing to better survival with either of the anti-cytokine therapies.

Forrest plot with subgroup analysis of case-fatality rates according to the clinical and laboratory characteristics. Bars to the left of the reference line indicate superiority of ruxolitinib, to the right—superiority of dexamethasone. ULN = upper limit of normal. Max = maximal value documented in-hospital before anti-cytokine therapy. The cut off levels of absolute lymphocytes and hemoglobin represent local normal reference ranges

The analysis of complications demonstrated almost equal distribution of hematological adverse events between groups (Additional file 1: Table S6). Only grade 1 thrombocytopenia was observed more often after ruxolitinib (37% vs 23%, p = 0.042). The incidence of grade 2–4 thrombocytopenia was not different between the groups (4.1% vs 3.4%). However, fewer severe cardiovascular adverse events were observed in the ruxolitinib group (6.8% vs 15%, p = 0.025), including reduction in the incidence of pulmonary embolism (2.0% vs 7.5%, p = 0.028) and trend to decreased incidence of acute myocardial infarction (4.8% vs 10.3%, p = 0.076). Incidence of deep vein thrombosis was not different between two arms (1.4% vs 1.4%, p = 1.0). Overall incidence of secondary severe infectious adverse events was not different between groups (7.5% vs 9.6%, p = 0.53). The incidence of nosocomial bacterial pneumonias (3.4% vs 4.1, p = 0.76) and sepsis (4.1% vs 6.1%, p = 0.43) was also not different in the ruxolitinib and dexamethasone groups, respectively. The list of rare adverse events is presented in Additional file 1: Table S7. All rare adverse events occurred no earlier than day 5 of the ruxolitinib treatment. In three cases (toxic hepatitis grade 3, gastrointestinal bleeding and spontaneous intra-abdominal hemorrhage) the therapy was changed to the conventional dexamethasone treatment (16–24 mg).

Discussion

Although WHO does not recommend routine use of immunosuppressive therapies [20], dexamethasone [9] and JAK inhibitor, baricitinib [10], were the few agents that demonstrated improvement of survival in large populations of patients with severe COVID-19 infection. In our study in the general group there were no significant differences between the evaluated agents in prevention of death from COVID-19, however dexamethasone administration was associated with faster hospital discharge. Despite absence of survival advantage in the general population, during the matching process we observed that COVID-19 is a very heterogeneous disease. This might be the reason for the failure of several randomized trials [6, 21]. Thus in attempts to find a universal cure for all COVID-19 patients it is important to formulate which patient population is the candidate for immunosuppressive therapy and what kind of anti-cytokine therapy should be applied in different clinical situations.

It is clear that at least in part this heterogeneity in COVID-19 patients comes from HIS clinical presentation. Before COVID-19 pandemic, it was evident that each etiology of HIS, or CRS, is associated with unique clinical features. CRS after chimeric antigen receptor T cells is characterized by neurotoxicity and hypotension [22]. In rheumatic diseases most common clinical features are hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, polyserositis and cytopenias [23]. In sepsis and hematological malignancies it is multiorgan failure with overproduction of serum ferritin [24, 25]. HIS in severe COVID-19 is another distinct entity with mild to moderate organ damage, but severe endothelial dysfunction, ARDS, hypercoagulation state and microangiopathy-like cytopenias [2, 26, 27]. Renal pathological findings in COVID-19 HIS are also quite unique and are characterized by tubular damage with abnormal sodium reabsorption, microangiopathy with hypoperfusion and glomerulopathy [28].

We observed that ruxolitinib improved survival in patients with a persistent fever (> 38.5 °C), which is one of the key features of COVID-19 HIS [2]. Besides fever, other clinical features of HIS, like acute renal injury or high CRP were not associated with a statistically significant superiority of ruxolitinib (probably, since they were observed in minor subsets of patients). So with the current study size, we were unable to formulate the exact HIS features where patients can benefit from ruxolitinib. However, the ability of ruxolitinib to control inflammation with endothelial damage is not unexpected. It was recently approved for steroid-refractory GVHD after allogeneic stem cell transplantation [12]. Steroid-refractory GVHD is another hyperinflammatory condition with severe endothelial dysfunction [29, 30]. The unique role of ruxolitinib in the situation of abnormal inflammation and endothelial dysfunction is confirmed by the fact that it is the first therapy approved for steroid-refractory acute GVHD in 30 years despite multiple academic studies of various immunosuppressive agents [31, 32]. Thus, it is unclear if other anti-cytokine therapies will provide similar results to JAK inhibitors.

On the contrary, case-fatality rates were comparable between dexamethasone and ruxolitinib across all subgroups of pulmonary severity defined by SpO2 level and computer tomography stage. Absence of difference can be explained by complex pathogenesis of lung injury in COVID-19. It was reported that besides HIS-associated interstitial edema and endothelial dysfunction, the following events may contribute to the damage: thrombosis of large and small vessels, formation of hyaline membranes, complement-associated injury, impaired surfactant production and direct viral cell injury [33,34,35]. Thus both dexamethasone and ruxolitinib may ameliorate HIS-associated components of lung injury, but not the others.

The major concern about anti-cytokine therapies, which was also stated in the WHO treatment guidelines [20], is the risk of secondary infections and other complications. Although the rate of hospital acquired infections varies across countries, in the studied cohort their incidence was comparable to an intensive care of other conditions [36]. Hematological toxicity is a known complication of ruxolitinib, however it is generally observed in patients with underlying hematological disease [11, 12]. In the doses used in this study, no clinically relevant hematological toxicity was observed. Although grade 1 thrombocytopenia was more prevalent after ruxolitinib, in some patients we observed, on the contrary, resolution of HIS-associated cytopenias during treatment. The reduced incidence of cardiovascular adverse events is not surprising. On the one hand, COVID-19 infection itself predisposes to venous thromboembolism, and some studies report the incidence of this complication as high as 37% [37]. On the other hand, the prothrombotic effects of steroids are known for a long time [38]. High incidence of myocardial infarction and venous thromboembolism emerged despite direct anticoagulation therapy in all patients. One of the possible explanations is the microangiopathic origin of thrombosis during COVID-19 infection, where anti-complement therapy might be a more effective way to prevent thrombotic events [39].

Conclusion

In the general cohort of patients with severe COVID-19 infection there was not statistically significant difference in case-fatality rate between ruxolitinib as initial therapy and dexamethasone. Our results confirm a favorable safety profile seen with another JAK inhibitor, baricitinib, in the randomized trial [10]. Presumable survival benefits of ruxolitinib group were observed in the patients with a high fever (≥ 38.5 °C) and without additional cardiovascular co-morbidity. However, these findings should be proved in a separate study. The recently announced results of randomized RUXCOVID trial demonstrated no difference in the primary composite endpoint [16], but still it is unclear if this result is generalizable for all the subpopulations defined with HIS symptoms and COVID-19 severity. Hence, the final consideration about JAK inhibitors efficiency should be drawn on the basis of additional studies.

Limitations of the study

The proposed research has the following limitations. This study was based on a patient population with COVID-19, who were undergoing in-hospital treatment in Saint-Petersburg in spring–autumn of 2020. Thus the described results refer to the disease caused by the Wuhan strain of SARS-CoV-2. Although the incidence of death was not significantly different in two groups, faster hospital discharge in the dexamethasone group may indicate that ruxolitinib was prescribed to “more severe patients” (from physicians’ subjective point of view). Thus some residual disbalance after matching could occur and dilute the effect of the therapy. This effect could be strengthened by the fact that some additional clinic features of patients could influence a doctor’s decisions regarding anti-cytokine therapy prescription but were not described in initial. Also, a few important complications of COVID-19 remained out of scope in this study and were not compared between groups. Some benefits of ruxolitinib found in high-fever and non-cardiovascular subgroups are based on unadjusted comparisons and hence should be proved in separate studies with a justified sample size.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CT:

-

Computer tomography

- DIS:

-

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- GM-CSF:

-

Granulocyte-monocyte colony stimulating factor

- GVHD:

-

Graft-versus host disease

- HIS:

-

Hyperinflammatory syndrome

- IL-1:

-

Interleukin-1

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- JAK:

-

Januse-kinase

- MAP:

-

Managed Access Program

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Stebbing J, Phelan A, Griffin I, et al. COVID-19: combining antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatments. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:400–2.

Webb BJ, Peltan ID, Jensen P, et al. Clinical criteria for COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(12):e754–63.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506.

Zizzo G, Cohen PL. Imperfect storm: is interleukin-33 the Achilles heel of COVID-19? Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(12):e779–90.

Leisman DE, Ronner L, Pinotti R, et al. Cytokine elevation in severe and critical COVID-19: a rapid systematic review, meta-analysis, and comparison with other inflammatory syndromes. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(12):1233–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30404-5 (Epub 2020 Oct 16).

Stone JH, Frigault MJ, Serling-Boyd NJ, BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial Investigators, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2333–44. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2028836 (Epub 2020 Oct 21).

Landi L, Ravaglia C, Russo E, et al. Blockage of interleukin-1β with canakinumab in patients with Covid-19. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21775. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78492-y.

Temesgen Z, Assi M, Shweta FNU, et al. GM-CSF neutralization with lenzilumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia: a case-cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(11):2382–94.

RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693–704.

Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:795–807.

Cervantes F, Vannucchi AM, Kiladjian JJ et al. Three-year efficacy, safety, and survival findings from COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study comparing ruxolitinib with best available therapy for myelofibrosis. Blood. 2013;122(25):4047–53.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-02-485888. Erratum in: Blood. 2016;128(25):3013. (Epub 2013 Oct 30).

Zeiser R, von Bubnoff N, Butler J, et al. Ruxolitinib for glucocorticoid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1800–10.

Ahmed A, Merrill SA, Alsawah F, et al. Ruxolitinib in adult patients with secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an open-label, single-centre, pilot trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(12):e630–7.

Vannucchi AM, Sordi B, Morettini A, et al. Compassionate use of JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib for severe COVID-19: a prospective observational study. Leukemia. 2020;35:1121–33 (published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 19).

La Rosée F, Bremer HC, Gehrke I, Kehr A, Hochhaus A, Birndt S, et al. The Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib in COVID-19 with severe systemic hyperinflammation. Leukemia. 2020;34:1805–15.

https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-provides-update-ruxcovid-study-ruxolitinib-hospitalized-patients-covid-19. Accessed 01/2021.

Ministry of Health temporary recommendations for prevention, diagnostics and treatment of new coronavirus infection (COVID-19). https://minzdrav.gov.ru/ministry/med_covid19. Accessed 01/2021.

WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection. A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(8):e192–7.

Dodd LE, Follmann D, Wang J, Koenig F, Korn LL, Schoergenhofer C, Proschan M, Hunsberger S, Bonnett T, Makowski M, Belhadi D, Wang Y, Cao B, Mentre F, Jaki T. Endpoints for randomized controlled clinical trials for COVID-19 treatments. Clin Trials. 2020;17(5):472–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774520939938 (Epub 2020 Jul 16).

World Health Organization. Clinical management of COVID-19: interim guidance. WHO Reference Number: WHO/2019-nCoV/clinical/2020.5.

Simonovich VA, Burgos Pratx LD, PlasmAr Study Group, et al. A randomized trial of convalescent plasma in Covid-19 severe pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2031304 (Epub ahead of print).

Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy—assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(1):47–62.

Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613–20.

Karakike E, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Macrophage activation-like syndrome: a distinct entity leading to early death in sepsis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:55.

Strenger V, Merth G, Lackner H, Aberle SW, Kessler HH, Seidel MG, Schwinger W, Sperl D, Sovinz P, Karastaneva A, Benesch M, Urban C. Malignancy and chemotherapy induced haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children and adolescents-a single centre experience of 20 years. Ann Hematol. 2018;97(6):989–98.

Diorio C, McNerney KO, Lambert M, et al. Evidence of thrombotic microangiopathy in children with SARS-CoV-2 across the spectrum of clinical presentations. Blood Adv. 2020;4(23):6051–63.

Ranucci M, Ballotta A, Di Dedda U, et al. The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1747–51.

Ng JH, Bijol V, Sparks MA, et al. Pathophysiology and pathology of acute kidney injury in patients with COVID-19. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27(5):365–76.

Luft T, Benner A, Jodele S, et al. EASIX in patients with acute graft-versus-host disease: a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(9):e414–23.

Dietrich S, Falk CS, Benner A, et al. Endothelial vulnerability and endothelial damage are associated with risk of graft-versus-host disease and response to steroid treatment. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(1):22–7.

Killock D. REACH2: ruxolitinib for refractory aGvHD. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(8):451.

Martin PJ, Rizzo JD, Wingard JR, et al. First- and second-line systemic treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease: recommendations of the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(8):1150–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.04.005.

Borczuk AC, Salvatore SP, Seshan SV, et al. COVID-19 pulmonary pathology: a multi-institutional autopsy cohort from Italy and New York City. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(11):2156–68.

Laurence J, Mulvey JJ, Seshadri M, et al. Anti-complement C5 therapy with eculizumab in three cases of critical COVID-19. Clin Immunol. 2020;219:108555.

Islam ABMMK, Khan MA. Lung transcriptome of a COVID-19 patient and systems biology predictions suggest impaired surfactant production which may be druggable by surfactant therapy. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19395.

World Health Organisation. Prevention of hospital-acquired infections. A practical guide 2nd edition. WHO/CDS/CSR/EPH/2002.12.

Pellegrini JAS, Rech TH, Schwarz P, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism among patients with severe COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation compared to other causes of respiratory failure: a prospective cohort study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-021-02395-6 (Epub ahead of print).

Ozsoylu S, Strauss HS, Diamond LK. Effects of corticosteroids on coagulation of the blood. Nature. 1962;195:1214–5.

Annane D, Heming N, Grimaldi-Bensouda L, COVID 19 Collaborative Group, et al. Eculizumab as an emergency treatment for adult patients with severe COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: a proof-of-concept study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28:100590.

Acknowledgements

We thank Novartis for providing access to ruxolitinib through Managed Access Program.

Funding

Ruxolitinib was obtained from Novartis through Managed Access Program (MAP).

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Agreement № 075-15-2021-1086, contract № RF––193021X0015).

The funding body had not participated in the study design, collecting data, data analysis, interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript, but took part in approval of final version of the manuscript before submitting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OS, EB, AK, IM designed the study and took part in the data analysis. OS, DF, IB, SG, VB, AL, EV, NB interpreted the clinical data and provided the appropriate information about the course of the disease. OS, EB, AK, IM analyzed and interpreted the acquired information from healthcare workers. OS, EB, DL, IS, TS, AK, IM, YP, SV, ML have drafted the work and substantively revised it. OS and EB have equal contribution to this study. All authors have approved the submitted version (and any substantially modified version that involves the author's contribution to the study). All authors have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirm all relevant ethical guidelines have been followed, and any necessary IRB and ethics committee approvals have been obtained.

The study protocol was submitted and approved by the biomedical ethics committee of I.P. Pavlov First Saint Petersburg State Medical University.

Informed written consent from all participants was obtained during the study.

All necessary and appropriate institutional forms from patients were archived.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

I.S.M. had received travel grants from MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Celgene, Takeda, BMS, consulting fees from Novartis and Celgene, lecturer fees from Novartis, Takeda and Johnson&Johnson.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Additional Figures S1–S8 and Tables S1–S7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Stanevich, O.V., Fomina, D.S., Bakulin, I.G. et al. Ruxolitinib versus dexamethasone in hospitalized adults with COVID-19: multicenter matched cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 21, 1277 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06982-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06982-z