Abstract

Background

The objectives of this study were to determine for the first time, in Morocco, the nasal carriage rate, antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and virulence genes of Staphylococcus. aureus isolated from animals and breeders in close contact.

Methods

From 2015 to 2016, 421 nasal swab samples were collected from 26 different livestock areas in Tangier. Antimicrobial susceptibility phenotypes were determined by disk diffusion according to EUCAST 2015. The presence of nuc, mecA, mecC, lukS/F-PV, and tst genes were determined by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for all isolates.

Results

The overall S. aureus nasal carriage rate was low in animals (9.97%) and high in breeders (60%) with a statistically significant difference, (OR = 13.536; 95% CI = 7.070–25.912; p < 0.001). In general, S. aureus strains were susceptible to the majority of antibiotics and the highest resistance rates were found against tetracycline (16.7% in animals and 10% in breeders). No Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was detected in animals and breeders. A high rate of tst and lukS/F-PV genes has been recovered only from animals (11.9 and 16.7%, respectively).

Conclusion

Despite the lower rate of nasal carriage of S. aureus and the absence of MRSA strains in our study, S. aureus strains harbored a higher frequency of tst and lukS/F-PV virulence genes, which is associated to an increased risk of infection dissemination in humans. This highlights the need for further larger and multi-center studies to better define the transmission of the pathogenic S. aureus between livestock, environment, and humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Staphylococcus aureus, especially, methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains (MRSA) are considered as major pathogens that infect and/or colonize both humans and animals [1]. Providing a reservoir of the pathogen, nasal carriage has been shown to be a predisposing factor for infections [2]. The emergence of MRSA is linked to the acquisition of the mecA gene that encodes for a low-affinity Penicillin-Binding Protein (PBP) [3] or its homologue mecC [4]. MRSA appeared firstly in a hospital in the early 1960s [5] and since then, it has been established around the world as an endemic hospital pathogen (Hospital Acquired-MRSA: HA-MRSA), and as Community-Acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) causing human infections in the community [6]. In addition to humans, MRSA colonization and infection have also been reported in a variety of animal species in many countries [7]. These strains known as Livestock associated MRSA (LA-MRSA) strains had a genetic origin which is different to that of human strains previously described, with isolates mainly belonging to clonal complex CC398 [8].

The emergence of LA-MRSA has also been increasingly associated with alarming rates of MRSA infection and colonization among humans in contact with livestock, suggesting an increased risk of zoonotic transmission [9, 10]. These pathogenic strains could be subsequently dispersed to the environment and to other species [7] through food chain [11] and direct contact [12,13,14]. Numerous studies have indicated that the increasing rate of the incidence of antimicrobial resistance in S. aureus in animals is a result of the misuse and unjustified utilization of antibiotics [11, 14, 15] in animal husbandry either, for therapeutic, preventive purposes or as growth promoters (GPs). The Moroccan authorities through the national food safety office [16] have launched a surveillance program for some antimicrobials used in animals since 2001. However, the overuse of antibiotics still represents a challenging issue and GPs such as tetracycline are still permitted with a veterinary prescription in Morocco [17].

In African countries, studies about nasal carriage of LA-MRSA seem to be scarce. The first report of ST398 in humans in Africa was published by Elhani et al. [18] who isolated one MRSA-ST398-t899 in the nasal sample of a farmer from Tunisia. In Morocco, Mourabit et al. [19] documented a 1.4% nasal carriage rate of MRSA in healthy humans. Interestingly, this work identified for the first time in Morocco one isolate characterized as MRSA-ST398-t011.

Moreover, two other studies performed in Tangier on milk and milk products [20] and on cockroaches and the house flies [21] revealed higher incidence of S. aureus and suggested the potential role for food and insects as source and/or reservoir of S. aureus infection.

In Tangier livestock, little is known about antibiotic-resistant S. aureus carriage among animals, particularly farm animals which are in close contact with humans. The objective of this work was to determine the rate of nasal carriage of S. aureus, and the antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in healthy farm animals and their breeders in Tangier.

Methods

Isolation and identification of nasal S. aureus isolates

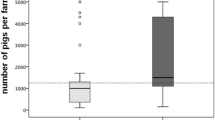

Livestock sampling areas included 16 small farms and 10 local sheep and goat farms in different regions of Tangier (Fig. 1). In general, the preference for selection of sampling sites was given to small farms or locals near the most populated areas of the city. In farms, the herd was composed of 20 to 50 heads. Among these, there were 4 to 15 cattle. The locals hosted less animals with a number not exceeding 20 heads and were composed essentially by sheep and goats (Table S1). This study was carried out between 2015 and 2016 and focused on clinically healthy animals and volunteers in close contact with these animals. To avoid a selection of resistant forms that can occur, no antibiotics within the last 3 months had been taken by animals [22]. Likewise, all the volunteers had no ongoing illness during the sampling period, and had not used antibiotics nor been hospitalized in the last three months [22].

Geographical distribution of the 26 Livestock sampling areas in different regions of Tangier. Figure 1 made using the q geographic information system (QGIS) version 2.2 and GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) version 2.10.20 software. Abbreviations: A−: Animal with no cases of S. aureus; A: Animal carrying multi-susceptible S. aureus; A+: Animal carrying S. aureus resistant to one antibiotic; A++: Animal carrying S. aureus resistant to two antibiotics; B−: Breeder with no cases of S. aureus; B: Breeder carrying multi-susceptible S. aureus; B+: Breeder carrying S. aureus resistant to one antibiotic; B++: Breeder carrying S. aureus resistant to two antibiotics; A/BPVL: Animal/Breeder carrying Panton–Valentine leukocidin-positive (PVL) S. aureus; A/BTSST-1: Animal/Breeder carrying Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin (TSST-1)-positive S. aureus. The map was created by the authors using the q geographic information system (QGIS) version 2.2 and GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) version 2.10.20 software

A nasal swab of both nostrils was done simultaneously for each of the animals and volunteer breeders.

Consent and ethics approval: As the majority of breeders were illiterate, informed oral consent was obtained from all participants following the explanation of the study objectives. This was approved by an internal Ethics Committee in the Faculty of Sciences and Techniques of Tangier. Confidentiality of the participants was maintained using unique code.

Phenotypic and molecular identification

To increase the chances of isolating the strains, the nasal samples were cultured in BHI medium and then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The isolation was carried out by successive subcultures on Chapman medium (Biorad) and on chromogenic media (UriSelect™ 4 dehydrated; Biorad), then incubated for 24 to 48 h at 37 °C.

Suspicious colonies were identified as S. aureus by colony morphology, Gram staining, catalase and DNase tests. One presumptively S. aureus isolate/sample was further confirmed by PCR for 16S rRNA and nuc genes, as previously described [3]. Susceptibility testing was performed with the disk diffusion method according to the recommendations of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST 2015) [23] for cefoxitin (30 μg), erythromycin (5 μg), lincomycin (15 μg), pristinamycin (15 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), tobramycin (10 μg), kanamycin (30 UI), tetracycline (30 UI), rifampicin (30 μg), chloramphenicol (10 μg), cotrimoxazole (23.75 ± 1.25 μg) and fusidic acid (10 μg). Inducible or constitutive lincomycin resistance was determined by the double disk diffusion test (D-test).

To avoid underestimating the prevalence of methicillin resistance, the presence of the mecA and mecC genes was determined by PCR in all these isolates, as previously described [3, 4]. All of the S. aureus isolates have been tested for the presence of lukS/F-PV and tst genes by PCR [24]. S. aureus strains ATCC 43300 (mecA-positive), ATCC 2011S359 (mecC-positive), ATCC 29213 (nuc-positive), MW2 (lukS/F-PV -positive) and FRI913 (tst-positive) were used as positive controls for PCRs.

All phenotypic and molecular tests were carried out in the Biotechnology and Biomolecule Engineering Research Laboratory.

Statistical analyses

Comparisons between proportions were drawn with Fisher’s exact test and the Chi-squared test. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were also calculated. Differences showing a p value < 0.05 were considered significant. Calculations were performed using SPSS version 20.0 software.

Results

Prevalence of S. aureus nasal carriage in farm animals

From 26 sampling sites (16 small farms and 10 local sheep and goat farms) in different regions of Tangier (Fig. 1; Table S1), a total of 421 different animals (cattle, sheep and goats) and 50 breeders were nasally screened. Phenotypic and molecular methods were able to isolate and identify forty-two (42/421, 9.97%) and thirty (30/50, 60%) strains from animals and breeders, respectively (OR = 13.536; 95% CI = 7.070–25.912; p < 0.001).

Sensitivity to antibiotics

Twenty-two (73.3%) in breeders and thirty-two (76.2%) in animals of S. aureus had no resistance to the antibiotics tested. All the isolates were susceptible to cefoxitin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole, tobramycin, gentamicin and chloramphenicol. The highest resistance rates were found for tetracycline (16.7 and 10%) and erythromycin (11.9 and 10%) in animals and breeders, respectively (Table 1). Screening for mecA and the mecC genes by PCR were negative. Of the resistant S. aureus isolates, six (6/8, 75%) and seven (7/10, 70%) recovered respectively from humans and animals presented resistance to one single antimicrobial drug. Co-resistance has been shown in two (2/8, 25%) isolates recovered from breeders and had as patterns (Tetracycline, Fusidic-acid); (Erythromycin, Fusidic-acid); and in three (3/10, 30%) isolates from animals with a unique pattern (Tetracycline, Erythromycin).

Exotoxin search

Of the 42 S. aureus isolates recovered from farm animals, 12 (28.57%) were toxinogenic. The genes encoding Panton Valentin Leucocidin toxin (PVL) and Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin (TSST-1) were only identified in seven (16.7%) and five (11.9%) strains from animals. Among these strains, no one co-harbored lukS/F-PV and tst genes. Interestingly, no toxinogenic strain was recovered from breeders. All the toxinogenic S. aureus recovered from animals presented susceptibility to all tested antibiotics, except one isolate methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA)-TSST+, which showed resistance to tetracyclin.

Discussion

In Morocco, livestock represents a large share of the Gross Domestic Product, which is between 25 and 30% according to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Rural Development, Water and Forests [25]. This activity, which still plays an important socio-economic role, involves nearly 70% of the rural population [26]. However, animal farming also develops around urban centers where several farms with less than 20 to 60 heads or more are located in working-class areas or on the outskirts of the city (Fig. 1).

In Tangier, no data about LA-MRSA nasal carriage has been reported yet. Our results revealed statistically lower prevalence of S. aureus nasal carriage in farm animals compared to breeders with a statistically significant difference (OR = 13.536; 95% CI = 7.070–25.912; p < 0.001). Unfortunately, we could not compare our results to Moroccan studies due to the lack of such data at the national and local scale. In a report from Tunisia including 261 healthy animals, a relatively lower rate of S. aureus (6.5%) was reported with different rates depending on animal species. Similarly to our findings, this group showed that all S. aureus isolates were MSSA [26]. In contrast, some studies investigating the distribution of S. aureus in different ecological niches from livestock in Algeria [27, 28] reported prevalence rates that are ranging from 18 to 53%f or S. aureus and 5.4 to 7.6% for MRSA. Moreover, a recent study conducted by Dweba et al. [13], in South African livestock production systems identified MRSA isolates in 27% with a significant relationship (p < 0.001) with the animal host.

The current report revealed that all strains were MSSA and no significant differences were identified in antimicrobial resistance between LA-strains and human isolates (p > 0.05) (Table 1). These similar antimicrobial susceptibility profiles may be due to the common shared environment and/or with the urban lifestyle associated breeding. Hence, bacteria could spread from the community, environment to animals, or vice versa [12, 14, 20, 29]. The animals studied in our report were housed in, confined spaces located in working-class areas and fed mainly food waste or, on the outskirts of the city where sanitation infrastructure was lacking. Certainly, contamination by antibiotic residues contaminating food waste or waste water may be evoked [29], but this remains to be confirmed by other samples from the environment. In addition, transmission of livestock bacteria could also occurred through manure and/or when being carried in the air or in the dust, as it has been previously shown [12]. Moreover, breeders or persons in contact could also be contaminated when handling fields using manure from conventional farms as fertilizer [30].

On the other hand, transmission of resistant strains could also occur via insects as it has been suggested by Bouammama et al. [21] in a study conducted on cockroaches and the houseflies collected from residential areas in Tangier. S. aureus isolated from the external bodies of these two species of insects represented 6.7% (17 cases) of which, one was identified as MRSA.

As discussed above, in addition to animal-to-human, environment to human and or/animals, bacterial strains could also be transmitted via contaminated food such as milk and milk products or meat and meat products [14], when handling raw food with bare hands. In the same region of North of Morocco, another study conducted by Bendahou et al. [20] about milk and milk products revealed a higher rate of S. aureus (40%). The antimicrobial susceptibility-profile of the isolated staphylococcal strains in this study was similar to our findings (25 and 10% for tetracyclin and erythromycin resistance, respectively).

In Morocco, recent reports have documented the massive use of antibiotics in food producing animals for curative and prophylactic purposes, which may induce the development of resistance to antibiotics and persistence of residues in animal products [17]. Rahmatallah et al. reported that resistance to tetracycline exceeded 90% in the tested strains. This molecule which, is frequently sold as GPs has probably an important role in the selection of resistant strains [15, 17].

To the best of our knowledge, the present study reports for the first time toxinogenic S. aureus strains, recovered from healthy farm animals in Tangier. The detection of MSSA PVL+ and MSSA TSST-1+ is relevant due to the important role that these toxins seem to play in serious infections in humans and animals [28, 31]. Such pathogenic strains could spread between different ecological niches and through the food chain causing subsequently major problems for the healthcare system [27, 31]. Mairi et al. suggested that MSSA strains might become a permanent reservoir of the luk S/F-PV genes that caused human infections [27].

We have previously described nasal carriage of toxinogenic strains S. aureus in healthy persons, in the same geographical area with 11.5% (46/400) harboring luk S/F-PV and 15.5% (62/400) tst genes. Some of these TSST-1 strains were found to be MRSA; however, all of the PVL+ were MSSA [19].

The current study shows several limitations. The nasal carriage of S. aureus could be transient and therefore some cases may go unnoticed at the time of our investigation. Furthermore, other unexplored sites including the extra nasal ones could also host this germ. Additionally, our screening survey was limited to tst and lukS/F-PV genes. However, nasal carriage strains could harbor additional virulence factors that may aggravate their pathogenicity in both animals and humans. The limited size of the sample is another limitation of our work, which probably influenced the statistical results. Finally, the clonality of strains was not determined to check the type of ST found in animals and humans.

Conclusion

Our nasal carriage study determined, for the first time in Tangier, a low prevalence of S. aureus with the absence of MRSA among farm animals. S. aureus strains harbored a higher rate of tst and lukS/F-PV genes, which is associated with an increased risk of dissemination of these strains in humans, animals and environment. Further studies are needed to better define the transmission of the pathogenic S. aureus between livestock, environment and humans.

Availability of data and materials

All data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- S. aureus :

-

Staphylococcus aureus

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus

- MSSA:

-

Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus

- PBP:

-

Penicillin-Binding Protein

- HA-MRSA:

-

Hospital Acquired-MRSA

- CA-MRSA:

-

Community-Acquired MRSA

- LA-MRSA:

-

Livestock associated MRSA

- CC:

-

Clonal complex

- GPs:

-

Growth promoters

- EUCAST:

-

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- PVL:

-

Panton Valentin Leucocidin toxin

- TSST-1:

-

Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin

References

Nemeghaire S, Argudin MA, Haesebrouck F, Butaye P. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage isolates from bovines. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:153.

Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, Van Leeuwen W, Van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, et al. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infec Dis. 2005;5:751–62.

Maes N, Magdalena J, Rottiers S, De Gheldre Y, Struelens MJ. Evaluation of a triplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay to discriminate Staphylococcus aureus from coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) and determine methicillin resistance from blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1514–7.

Garcia-Alvarez L, Holden MT, Lindsay H, Webb CR, Brown DF, Curran MD, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a novel mecA homologue in human and bovine populations in the UK and Denmark: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:595–603.

Jevons MP, Coe AW, Parker MT. Methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Lancet. 1963;1:904–7.

Vandenesch F, Naimi T, Enright MC, Lina G, Nimmo GR, Heffeman H, et al. Community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:978–84.

Cuny C, Friedrich A, Kozytska S, Layer F, Nubel U, Ohlsen K, et al. Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in different animal species. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:109–17.

Guardabassi L, Stegger M, Skov R. Retrospective detection of methicillin resistant and susceptible Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in Danish slaughter pigs. Vet Microbiol. 2007;122(3–4):384–6.

Hanselman BA, Kruth SA, Rousseau J, Low DE, Willey BM, McGeer A, et al. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in veterinary personnel. Emerg. Infect Dis. 2006;12:1933–8.

Spoor LE, McAdam PR, Weinert LA, Rambaut A, Hasman H, Aarestrup FM, et al. Livestock origin for a human pandemic clone of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. mBio. 2013;4(4):e00356–13.

Kluytmans JA. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in food products: cause for concern or case for complacency? Clin Microbiol. Infect. 2010;16:11–5.

Schulz J, Friese A, Klees S, Tenhagen BA, Fetsch A, Rosler U, et al. Longitudinal study of the contamination of air and of soil surfaces in the vicinity of pig barns by livestock-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:5666–71.

Dweba CC, Zishiri O, El Zowalaty M. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: livestock-associated, antimicrobial, and heavy metal resistance. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:2497–509.

Gundogan N, Citak S, Yucel N, Devren A. A note on the incidence and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from meat and chicken samples. Meat Sci. 2005;69(4):807–10.

Aarestrup FM. Association between consumption of antimicrobial agents in animal husbandry and the occurrence of resistant bacteria among food animals. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;12:279–85.

Office national de sécurité sanitaire des aliments (ONSSA). Requirements for poultry production. 2015. Available from http://www.onssa.gov.ma/fr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=187&Itemid=126. (Accessed 10 March 2015).

Rahmatallah N, El Rhaffouli H, Lahlou Amine I, Sekhsokh Y, FassiFihri O, El Houadfi M. Consumption of antibacterial molecules in broiler production in Morocco. Vet Med Sci. 2018;4(2):80–90.

Elhani D, Gharsa H, Kalai D, Lozano C, Gomez P, Boutheima J, et al. Clonal lineages detected among tetracycline resistant MRSA isolates of a Tunisian hospital, with detection of lineage ST398. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:623–32.

Mourabit N, Arakrak A, Bakkali M, Laglaoui A. Nasal carriage of sequence type 22 MRSA and livestock-associated ST398 clones in Tangier, Morocco. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2017;11:536–42.

Bendahou A, Abid M, Bouteldoun N, Catelejine D, Lebbadi M. Staphylocoque à coagulase positive entérotoxinogène dans le lait et les produits laitiers, lben et jben, dans le nord du Maroc. J Infect DevCtries. 2009;3:169–76.

Bouamamaa L, Sorlozano A, Laglaoui A, Lebbadi M, Aarab A, Gutierrez J. Profils de résistance aux antibiotiques des souches bactériennes isolées de Periplaneta americana et Muscadomestica à Tanger, Maroc. J Infect DevCtries. 2010;4:194–201.

Levy SB. Factors impacting on the problem of antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemotherapy. 2002;49(1):25–30.

The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 5.0. 2015. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_5.0_Breakpoint_Table_01.pdf (Accessed on 10 April 2015).

Denis O, Deplano A, De Beehouwer H, Hallin M, Huysmans G, Garrino MG, et al. Polyclonal emergence and importation of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains harbouring Panton-valentine leucocidin genes in Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:1103–6.

Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Rural Development, Water and Forests (MAF). 2014. http://www.agriculture.gov.ma/en.

Gharsa H, Ben Slama K, Gomez-Sanz E, Lozano C, Zarazaga M, Messadi L, et al. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus from nasal samples of healthy farm animals and pets in Tunisia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015;15(2):109–15.

Mairi A, Touati A, Pantel A, Zenati K, Martinez AY, Dunyach-Remy C, et al. Distribution of Toxinogenic methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus from different ecological niches in Algeria. Toxins (Basel). 2019;11(9):500.

Agabou A, Ouchenane Z, NgbaEssebe C, Khemissi S, Chehboub MTE, Chehboub IB, et al. Emergence of nasal carriage of ST80 and ST152 PVL + Staphylococcus aureus isolates from livestock in Algeria. Toxins (Basel). 2017;9:303.

Ezzariai A, Hafidi M, Khadra A, Aemig Q, El Fels L, Barret M, et al. Human and veterinary antibiotics during composting of sludge or manure: global perspectives on persistence, degradation, and resistance genes. J Hazard Mater. 2018;359:465–81.

Casey JA, Curriero FC, Cosgrove SE, Nachman KE, Schwartz BS. High-density livestock operations, crop field application of manure, and risk of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in Pennsylvania. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1980–90.

Otto M. Staphylococcus aureus toxins. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;17:32–7.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the breeders, and the person who allowed us to collect samples for this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NM designed, organized, collected the nasal samples and wrote the first draft of the paper. MB and AA performed data analysis and interpretation. ZZ and JB drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. AL designed the study, helped with data analysis and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and were responsible for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by an internal Ethics Committee in the Faculty of Sciences and Techniques of Tangier. As the majority of breeders were illiterate, informed oral consent was obtained from all participants following the explanation of the objectives of the study. This verbal consent was approved by an internal Ethics Committee in the Faculty of Sciences and Techniques of Tangier. Confidentiality of the participants was maintained using unique code.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No conflict of interests is declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1

: Numbers, antimicrobial susceptibility and toxin gene profiles of the Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from breeders and animals in Tangier.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mourabit, N., Arakrak, A., Bakkali, M. et al. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in farm animals and breeders in north of Morocco. BMC Infect Dis 20, 602 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05329-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05329-4