Abstract

Background

Bacterial diarrhoeal disease is among the most common causes of mortality and morbidity in children 0–59 months at the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. However, most cases are treated empirically without the knowledge of aetiological agents or antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. The aim of this study was, therefore, to identify bacterial causes of diarrhoea and determine their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in stool specimens obtained from the children at the hospital.

Methods

This hospital-based cross-sectional study involved children aged 0–59 months presenting with diarrhoea at paediatrics wards at the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia, from January to May 2016. Stool samples were cultured on standard media for enteropathogenic bacteria, and identified further by biochemical tests. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction was used for characterization of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli strains. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed on antibiotics that are commonly prescribed at the hospital using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method, which was performed using the Clinical Laboratory Standards International guidelines.

Results

Of the 271 stool samples analysed Vibrio cholerae 01 subtype and Ogawa serotype was the most commonly detected pathogen (40.8%), followed by Salmonella species (25.5%), diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli (18%), Shigella species (14.4%) and Campylobacter species (3.5%). The majority of the bacterial pathogens were resistant to two or more drugs tested, with ampicillin and co-trimoxazole being the most ineffective drugs. All diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli isolates were extended spectrum β-lactamase producers.

Conclusion

Five different groups of bacterial pathogens were isolated from the stool specimens, and the majority of these organisms were multidrug resistant. These data calls for urgent revision of the current empiric treatment of diarrhoea in children using ampicillin and co-trimoxazole, and emphasizes the need for continuous antimicrobial surveillance as well as the implementation of prevention programmes for childhood diarrhoea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infectious diarrhoea is a significant cause of illness and death among children under 5 years of age in low-resource countries. It accounts for 9% of all deaths globally in this age group, and ranks only second to pneumonia [1]. The majority of these cases are associated with the first two years of life, with peak ages being between 6 and 11 months [1, 2]. Although mortality associated with diarrhoea has been decreasing since 2000, mainly due to the implementation of effective control programmes and improved socioeconomic status, it still remains an important reason for hospital admissions and deaths among the children [3]. South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa bear the highest burden of the disease [1, 4].

Interventions that target the main causes of diarrhoea should focus on the most susceptible children, and this should further accelerate decline of diarrhoeal cases. Guiding these efforts requires identification of aetiological agents and understanding the risk factors associated with diarrhoea. Most cases of diarrhoea are associated with consumption of contaminated water and food, and poor sanitation, which create an ideal environment for diarrhoeal pathogens to be easily transmitted [2, 5]. Several pathogens have been implicated as important causes of diarrhoea, and these include a variety of bacteria, parasites and viruses [4, 6, 7].

Although the most effective treatment for acute diarrhoea is fluid and electrolyte replacement, antibacterial agents are often indicated in dysentery, typhoid fever and severe cholera [3, 8]. However, in recent years there has been growing concern of antimicrobial resistance in bacterial pathogens associated with diarrhoea [9–11]. Thus, there is an urgent need for global surveillance of antimicrobial resistance as this is important in the management of children with diarrhoea [12].

Despite diarrhoea in children being acknowledged as a serious public health problem in Zambia, there is a paucity of data on infectious diarrhoeal agents, especially bacterial pathogens and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns due to the few studies that have been conducted in the country [13–15]. Since aetiological agents and drug resistance patterns vary greatly across countries, regions and communities over time, current local knowledge of these patterns is essential to inform treatment, prevention and control programmes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify bacterial pathogens in stool samples obtained from children aged 0–59 months admitted with diarrhea to the University Teaching Hospital (UTH) in Lusaka, Zambia.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted at the University Teaching Hospital (UTH), a tertiary referral and teaching hospital in Lusaka with a bed capacity of approximately 2000, and is also the reference centre for all microbiology diagnostic work in Zambia.

Type of study

This was a cross sectional study. Stool samples were collected from children aged 0–59 months with diarrhoea who attended the UTH from December 2015 to April 2016. Samples were submitted to the microbiology laboratory to determine the presence of bacterial enteropathogens and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns.

Isolation and identification of bacterial enteropathogens

Stool samples were inoculated onto MacConkey, Deoxycholate Citrate Agar (DCA) and Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD) agar plates (Mast Diagnostics Ltd, Merseyside, UK). Samples from suspected cases of cholera were first inoculated into alkaline peptone water and subcultured onto Thiosulphate Citrate Bile Salt (TCBS) (Mast Diagnostics Ltd, Merseyside, UK). All cultures were incubated at 35–37 °C for 12–18 h except for the modified Charcoal-Cefoperazone Deoxycholate Agar (mCCDA) plates (Himedia, Mumbai, India), which were incubated at 42 °C for 72 h in a candle jar sealed with parafilm (Parafilm M, Pechiney Plastic Packaging, Chicago, USA). C. jejuni ATCC 33291 strain was used as a positive control. Figure 1 show the approach used for the identification process for the bacterial enteropathogens.

For the identification of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli (DEC), DNA from the isolates was extracted on the easyMag instrument (bioMérieux, Marcy I’Etoile, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the “on-board lysis” protocol. DNA was eluted in a final volume of 110 μl. All isolates identified as E. coli were screened further for virulence genes by multiplex real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) targeting specific genes that are associated with six different pathotypes of DEC: enteropathogenic E. coli (ETEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC and diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC). The minimum criteria for determining diarrhoeagenic E. coli were defined as the presence of stIa/stIb and lt for ETEC, presence of ipaH for EIEC, presence of eaeA for EPEC, presence of aggR for EAEC, stx 1 and stx 2 for STEC and daaD for DAEC [16]. The PCR assay was carried out as previously described [16]. E. coli DH5α, which lacks all the diarrhoeagenic genes, was used as a negative control. The PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR cycler (Life Technologies, California, USA) (Fig. 1).

Antimicrobial susceptibility

This was performed by the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method using the CLSI guidelines [17] on Müeller-Hinton agar plates (Mast Diagnostics Ltd, Merseyside, UK) (Table 1). Isolates of E. coli were also screened for Extended Spectrum β-Lactamases (ESBL) production by testing them against cefpodoxime (10 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), and cefotaxime (30 μg) (Mast Diagnostics Ltd, Merseyside, UK) as indicator cephalosporins [18]. Production of ESBLs was confirmed phenotypically by using the combination discs on Müeller-Hinton agar plates (Mast Diagnostics Ltd, Merseyside, UK): cefotaxime/clavulanic acid, cefpodoxime/clavulanic acid and ceftazidime/clavulanic acid (Mast Diagnostics Ltd, Merseyside, UK). After incubation for 18–24 h at 37 °C, the zones of inhibition of the indicator cephalosporin and cephalosporin/clavulanic acid were measured using Vernier callipers and compared. Confirmation of ESBL production was indicated by the zone size of the cephalosporin/clavulanic acid being greater than the indicator cephalosporin (i.e., ≥5 mm). E. coli ATCC 25922 and S. aureus ATCC 25923 were used as quality control strains for susceptibility testing.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism Software Version 5.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) and EpiInfo Version 7.1.5 Software (CDC, Atlanta, USA). Descriptive data analysis was utilized to determine the range of enteropathogens and distribution of study covariates.

Results

Isolation and identification of bacterial enteropathogens

Of the 271 children enrolled, 54.6% of them were boys, while the rest were girls (45.4%). Most of the children were less than 24 months (61.3%), followed by those aged between 48 and 59 months (15.5%), 24 to 35 months (12.6%) and 36 to 47 months (10.7%) (Table 2).

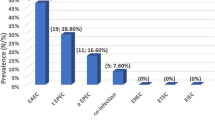

Culture results showed that 31.4% of the stool samples analysed were positive for five different bacterial enteropathogens: Vibrio cholerae (40.8%), Salmonella species (25.5%), DEC (18%), Shigella species (14.4%) and Campylobacter species (3.5%) (Table 3). All the V. cholerae isolates detected were of the 01 subtype and Ogawa serotype. Amongst the Salmonella species, 52.4%) were S. Typhi, 19.1% were S. Paratyphi B and 28.6% were Non-Typhoidal Salmonella (NTS). Of the DEC detected, the most frequent was ETEC (40%), followed by EIEC (26.7%), EAEC (20%), and EPEC (13.3%). No STEC or DEAC strains were detected. Of the 12 Shigella isolates, 50% were Shigella flexneri, 33.3% were Shigella dysenteriae and 16.7% were Shigella boydii. Campylobacter jejuni comprised only 3.5% of the total number of isolates (Table 3).

Vibrio cholerae and Salmonella species were most commonly recovered from children aged between 12 and 23 months. The most prevalent pathogen, V. cholerae, was detected mainly in children older than 12 months. DEC mainly affected children less than 12 months, while Shigella mainly affected children older than 36 months.

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns

All V. cholerae isolates exhibited 100% resistance to co-trimoxazole, nalidixic acid and nurafurantoin. The isolates showed low level of resistance to erythromycin (32.4%), ciprofloxacin (26.5%), norfloxacin (20.5%) and chloramphenicol (8.8%). All the isolates were 100% susceptible azithromycin, ampicillin, cefotaxime and gentamicin, while the strains were 94.1% sensitive and 5.9% intermediate to tetracycline.

We also attempted to find antimicrobial resistance patterns of the bacterial enteropathogens. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as resistance to three or more drugs. The majority of the V. cholera (97%) were MDR with 9 different patterns. The most common pattern was ciprofloxacin-cotrimoxazole-erythromycin-nalidixic acid (11.8%), followed by ciprofloxacin-cotrimoxazole-nalidixic acid-norfloxacin (8.8%) and cotrimoxazole-erythromycin-nalidixic acid (5.9%) (Table 4).

S. Typhi species displayed 100% resistance to ampicillin, co-trimoxazole and streptomycin, 72.7% to chloramphenicol, 18.2% to azithromycin and 9.1% to ciprofloxacin. The isolates isolates had four different MDR patterns, the commonest being ampicillin-chloramphenicol-cotrimoxazole-streptomycin (45/5%), followed by ampicillin-cotrimoxazole-streptomycin (36.4%), ampicillin-azithromycin-chloramphenicol-cotrimoxazole-streptomycin (18.2%) and ampicillin-chloramphenicol-ciprofloxacin-streptomycin (9.1%). However, these isolates were all susceptible to nalidixic acid, amoxycylin-clavulanic acid, tetracycline, spectinomycin, gentamicin, cefotaxime, neomycin and colistin. S. Paratyphi B isolates were 100% resistant to ampicillin, co-trimoxazole and streptomycin, chloramphenicol and 75% resistant to spectinomycin. Its MDR patterns were ampicillin-chloramphenicol-cotrimoxazole-spectinomycin-streptomycin (75%) and ampicillin-chloramphenicol-cotrimoxazole-streptomycin (25%). This group of Salmonella isolates were susceptible to azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, amoxycylin-clavulanic acid, gentamicin, cefotaxime, neomycin and colistin. The NTS isolates showed the following resistance patterns: 100% to co-trimoxazole, 88.3% to ampicillin, 66.7% to streptomycin, 50% to chloramphenicol, 33.3% to spectinomycin, and 16.7% to both colistin and tetracycline. The group had six different patterns each exhibiting 16.7% (Table 5). These isolates were also susceptible to the following antibiotics: to azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, amoxycylin-clavulanic acid, gentamicin, cefotaxime and neomycin.

DEC generally exhibited high rates of resistance to most antibiotics tested. ETEC strains were more resistant to co-trimoxazole (100%), followed by ampicillin and cefotaxime (66.7%), ceftazidime (66.7%), cefpodoxime (66.7%), tetracycline (both 50%), streptomycin (33.7), chloramphenicol and nalidixic acid (both 16.4%). The four types of DEC isolated showed 100% resistance to co-trimoxazole and each type was 50% resistant to tetracycline. The most resistant strains belonged to the EPEC group. The stains displayed the following MDR patterns: ETEC, six; EIEC, four; EAEC, three; and EPEC, two (Table 6).

After analysing all the 15 isolates of DEC for ESBL production, 66.7% (10/15) were found to be resistant to cefotaxime, ceftazidime and cefpodoxime, suggesting that they were potential producers of ESBL. Further analysis of the isolates with a confirmatory test (combination discs: cefotaxime-clavulanic acid, ceftazidime clavulanic acid and cefpodoxime clavulanic acid) showed that all of them were ESBL-producers.

Among the Shigella species, S. flexneri was resistant to ampicillin and co-trimoxazole (both 100%), followed by chloramphenicol and streptomycin (both 83.8%), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and tetracycline (both 16.5%). S. dysenteriae displayed 100% resistance to both ampicillin and co-trimoxazole (75%), to chloramphenicol (25%) and 25% to tetracycline. S. bodii was 100% resistant to ampicillin, co-trimoxazole and chloramphenicol. Their MDR patterns were as follows: flexneri, 4, the commonest being ampicillin-chloramphenicol-cotrimoxazole-streptomycin (50%); S. dysenteriae, 2, with ampicillin-chloramphenicol-cotrimoxazole-streptomycin being the commonest (75%); and both S. boydii displayed only two different patterns, ampicillin-chloramphenicol-cotrimoxazole (100%) (Table 7).

The three Campylobacter jejuni species isolated were only resistant to co-trimoxazole (100%), ampicillin (33.3%) and tetracycline (33.3%).

Discussion

Five different bacterial enteropathogens were isolated from some of the stool specimens, and these included V. cholerae 01 Ogawa serotype, Salmonella species, Shigella species, DEC and Campylobacter species. V. cholerae was the most predominant pathogen due to a cholera outbreak during the study period. Our results were in agreement with previous studies done in Lusaka [19, 20]. However, none of these studies focused on cholera in children.

Salmonella species was the second most prevalent genera (25.5%); and the majority of the species were S. Typhi followed by NTS and S. Paratyphi B, which agrees with other studies conducted in India and Bangladesh [21–23].

Among the DEC isolates, four strains were identified: ETEC, EIEC, EAEC and EPEC, with EPEC being the most predominant species. Four strains of DEC (ETEC, EIAC, EAEC and EPEC) were the third most common group of enteropathogens, accounting for 18.0% of all isolates. The predominance of ETEC strain, among the DEC, in agreement with previous studies carried out in Bangladesh, Tunisia and Kenya [24–26]. ETEC was associated with one third of diarrhoea cases identified in children in the recent GEMS Study [4].

DEC isolates were mainly recovered from children below the age of 24 months, which corroborates with the findings of a Nigerian study that also indicated that most of the DEC isolates were mostly recovered from this age group [27]. In this study, EAEC was detected from only 3 specimens, and EIEC and EPEC strains were also detected but in low numbers.

Shigella species ranked third, with the most predominant species being S. flexneri, and affected mainly children above 36 months of age. This finding was in conformity with previous studies that have implicated S. flexneri as the dominant species [28, 29]. However, other studies have indicated that S. dysenteriae and S. boydii to be more frequently isolated species [28–30].

Only three Campylobacter species were recovered from the children, which might probably be due to the fact that Campylobacter is as a fastidious organism which requires special conditions for growth [31]. However, in a community-based study on the pathogen-specific burden of diarrhoea in low-income countries, that involved eight study sites in South America, Africa and Asia, Campylobacter exhibited the highest attributable burden of diarrhoea amongst infants aged between 0 and 11 months [31].

In this study, all the organisms isolated exhibited high level drug resistance, including resistance to multiple drugs. V. cholerae isolates were totally resistant to cotrimoxazole and nalidixic acid, partially resistant to erythromycin, ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin. A previous study in Zambia, during the 1990–1991 major cholera outbreak, showed resistant to cotrimoxazole (97%), tetracycline (95%), chloramphenicol (98%) and doxycycline (70%) [19]. A similar study in Mozambique, found that the V. cholerae O1 Ogawa isolates were resistant to cotrimoxazole (100%), ampicillin (100%), nalidixic acid [9], chloramphenicol (97%), nitrofurantoin (95%), tetracycline (82%), azithromycin (56%) but sensitive to ciprofloxacin (100%) (101).

For the Salmonella species, both S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi B were totally resistant to ampicillin, cotrimoxazole and streptomycin. In addition to the three drugs, S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi B were also significantly resistant to chloramphenicol and spectinomycin, respectively. These findings are consistent with other studies in which it was noted that there was an increase in the number of Salmonella isolates being resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol and cotrimoxazole [32].

A study on the Malawi-Mozambique border reported findings similar to those in this study in which 100% of S. Typhi were resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol and cotrimoxazole [33]. Another study carried out in Uganda showed that 76% of S. Typhi isolates were resistant to ampicillin, streptomycin, sulfisoxazole, tetracycline, and cotrimoxazole, but were susceptible to chloramphenicol. This was in conformity with findings from this study which also found that all the S. Typhi isolates were susceptible to ceftaxime, gentamicin, and spectinomycin [34].

This study also demonstrated the occurrence of MDR strains of S. Typhi, S. Paratyphi B and the NTS which were resistant to all traditional first line drugs tested: ampicillin, chloramphenicol and cotrimoxazole. The commonest resistance pattern observed in this study was ampicillin-chloramphenicol-cotrimoxazole-streptomycin for S. Typhi, ampicillin-chloramphenicol-spectinomycin-cotrimoxazole- streptomycin for S. Paratyphi B, while NTS has 6 different patterns, which also included the ampicillin-chloramphenicol-spectinomycin-cotrimoxazole- streptomycin pattern. A similar study by Demczuk and colleagues [35], revealed 26 resistance patterns with the commonest patterns being nalidixic acid-resistant (NAR) and ampicillin-chloramphenicol-nalidixic acid-streptomycin-sulfisoxazole-cotrimoxazole in S. Typhi compared to this to this study. This study indicated that most of the Salmonella isolates were resistant to two or more antibiotics and there was variability in the resistant patterns of NTS. The MDR detection rates S. Typhi, S. Paratyphi B, and the NTS were all 100%. Similar findings of MDR strains (100%) were reported in Turkey [36].

All the DEC isolates were highly resistant to cotrimoxazole, ampicillin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefpodoxime, nalidixic acid, and tetracycline. Generally, the isolates showed moderate to high resistance to most drugs, and low resistance to streptomycin and chloramphenicol. Our data suggests the presence of MDR in all the DEC isolates (100%) recovered in this study. This high prevalence of MDR strains observed in this and other studies is worrisome in that it limits treatment options for the patients. Another important observation in this study with the DEC isolates was that they were all resistant to third generation cephalosporins used. Interesting, all the isolates proved to be ESBL-producers. The detection of ESBL-producing DEC isolates warrants attention in the context of increasing resistance amongst the enteropathogens. The high prevalence of ESBL in this study may suggest over prescription of third generation cephalosporins in or inappropriate use of antibiotics in Lusaka.

In this study all the Shigella species were mainly resistant to ampicillin, cotrimoxazole, chloramphenicol and streptomycin, although S. boydii was sensitive to streptomycin. The common resistance pattern was ampicillin-chloramphenicol-cotrimoxazole-streptomycin. These data suggest the presence of MDR in all the Shigella isolates (100%) recovered. This MDR pattern was in consonance with our study.

The two Campylobacter species isolated in this study were resistant to co-trimoxazole and moderately resistant to both ampicillin and tetracycline. In a Zimbabwean study, 50% of the isolates from humans and 82% from chickens were resistant to co-trimoxazole, while for ampicillin and tetracycline the levels were similar as those in this study. However, MDR resistant isolates were consistently susceptible to erythromycin, chloramphenicol and gentamicin [37].

Conclusion

This study isolated and identified five enteric bacteria from stools obtained from children with diarrhea and the majority of these organisms exhibited drug resistance to ampicillin and co-trimoxazole. This presents very limited treatment options for patients, necessitating a review of empirical treatment practices at the UTH to avoid further complications in affected patients. The study however, recommend good hygienic practices in different communities through public health educational programme in order to avoid cases diarrhoea infections among children.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

- DEC:

-

Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli

- DNA:

-

Deoxy Ribonucleic Acid

- ERES:

-

Excellence in Research Ethics and Science

- ESBL:

-

Extended Spectrum of Beta Lactamase

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- MDR:

-

Multi Drug Resistance

- MUHAS:

-

Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences

- NTS:

-

Non Typoidal Salmonella

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- TFELTP:

-

Tanzanian Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Management Training Programme

- UTH:

-

University Teaching Hospital

References

UNICEF. Pneumonia and diarrhoea: tackling the deadliest diseases for the world’s poorest children, vol. 2014. New York: UNICEF; 2012. p. 2–8.

Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1405–16.

Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Perin J, Rudan I, Lawn JE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):430–40.

Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case–control study. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):209–22.

Kimani HM. Assessement of diarrhoeal disease attributable to water, sanitation and hygiene among under five in Kasarani, Nairobi County. Department of Community Health, School of Public Health, Kenyatta University; 2013.

Lanata CF, Fischer-Walker CL, Olascoaga AC, Torres CX, Aryee MJ, Black RE. Global causes of diarrheal disease mortality in children < 5 years of age: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72788.

Moyo SJ, Gro N, Matee MI, Kitundu J, Myrmel H, Mylvaganam H, et al. Age specific aetiological agents of diarrhoea in hospitalized children aged less than five years in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11(1):1.

Bonkoungou IJO, Haukka K, Österblad M, Hakanen AJ, Traoré AS, Barro N, et al. Bacterial and viral etiology of childhood diarrhea in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):1.

Langendorf C, Le Hello S, Moumouni A, Gouali M, Mamaty A-A, Grais RF, et al. Enteric bacterial pathogens in children with diarrhea in Niger: diversity and antimicrobial resistance. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120275.

Hendriksen RS, Leekitcharoenphon P, Lukjancenko O, Lukwesa-Musyani C, Tambatamba B, Mwaba J, et al. Genomic signature of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar typhi isolates related to a massive outbreak in Zambia between 2010 and 2012. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(1):262–72.

Qu M, Lv B, Zhang X, Yan H, Huang Y, Qian H, et al. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of bacterial pathogens isolated from childhood diarrhea in Beijing, China (2010–2014). Gut Pathog. 2016;8(1):1.

Giannattasio A, Guarino A, Vecchio AL. Management of children with prolonged diarrhea. F1000Res. 2016;5(F1000 Faculty Rev):206. 10.12688/f1000research.7469.1.

Van der Hoek W, Van Oosterhout J, Ngoma M. An outbreak of dysentery in Zambia. S Afr Med J. 1996;86(1):93.

Nakano T, Kamiya H, Matsubayashi N, Watanabe M, Sakurai M, Honda T. Diagnosis of bacterial enteric infections in children in Zambia. Pediatr Int. 1998;40(3):259–63.

Mwansa J, Mutela K, Zulu I, Amadi B, Kelly P. Antimicrobial sensitivity in enterobacteria from AIDS patients, Zambia. (Dispatches). Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(1):92–4.

Barletta F, Ochoa TJ, Cleary TG. Multiplex real-time PCR (MRT-PCR) for diarrheagenic. Berlin: PCR Detection of Microbial Pathogens Springer; 2013. p. 307–14.

Cockerill FR. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twenty-first informational supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2011.

Mumbula EM, Kwenda G, Samutela MT, Kalonda A, Mwansa JC, Mwenya D, et al. Extended Spectrum β-Lactamases Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. J Med Sci Technol. 2015;4:2.

Mwansa J, Mwaba J, Lukwesa C, Bhuiyan N, Ansaruzzaman M, Ramamurthy T, et al. Multiply antibiotic-resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor strains emerge during cholera outbreaks in Zambia. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(5):847–53.

Marin M, Vicente A. Variants of Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor from Zambia showed new genotypes of ctxB. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140(08):1386–7.

Verma S, Thakur S, Kanga A, Singh G, Gupta P. Emerging Salmonella Paratyphi A enteric fever and changing trends in antimicrobial resistance pattern of salmonella in Shimla. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2010;28(1):51.

Afroz H, Hossain MM, Fakruddin M, Hossain MA, Khan ZUM, Datta S. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of bloodstream Salmonella infections in a tertiary care hospital, Dhaka. J Med Sci. 2013;13(5):360.

Baker S, Favorov M, Dougan G. Searching for the elusive typhoid diagnostic. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):1.

Nejma IBS-B, Zaafrane MH, Hassine F, Sdiri-Loulizi K, Said MB, Aouni M, et al. Etiology of acute diarrhea in Tunisian children with emphasis on diarrheagenic Escherichia coli: prevalence and identification of E. coli virulence markers. Iranian J Public Health. 2014;43(7):947.

Das SK, Ahmed S, Ferdous F, Farzana FD, Chisti MJ, Latham JR, et al. Etiological diversity of diarrhoeal disease in Bangladesh. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(12):900–9.

Boru WG, Kikuvi G, Omollo J, Abade A, Amwayi S, Ampofo W, et al. Aetiology and factors associated with bacterial diarrhoeal diseases amongst urban refugee children in Eastleigh, Kenya: a case control study. African J Lab Med. 2013;2(1):6.

Odetoyin BW, Hofmann J, Aboderin AO, Okeke IN. Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli in mother-child Pairs in Ile-Ife, South Western Nigeria. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):1.

Herwana E, Surjawidjaja JE, Salim OC, Indriani N, Bukitwetan P, Lesmana M. Shigella-associated diarrhea in children in South Jakarta, Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41(2):418–25.

Livio S, Strockbine NA, Panchalingam S, Tennant SM, Barry EM, Marohn ME, et al. Shigella isolates from the global enteric multicenter study inform vaccine development. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(7):933–41.

Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Muhsen K. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS): impetus, rationale, and genesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55 Suppl 4:S215–24.

Platts-Mills JA, Babji S, Bodhidatta L, Gratz J, Haque R, Havt A, et al. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: a multisite birth cohort study (MAL-ED). Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(9):e564–75.

Holt KE, Phan MD, Baker S, Duy PT, Nga TVT, Nair S, et al. Emergence of a globally dominant IncHI1 plasmid type associated with multiple drug resistant typhoid. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(7):e1245.

Lutterloh E, Likaka A, Sejvar J, Manda R, Naiene J, Monroe SS, et al. Multidrug-resistant typhoid fever with neurologic findings on the Malawi-Mozambique border. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1100–6.

Neil KP, Sodha SV, Lukwago L, Shikanga O, Mikoleit M, Simington SD, et al. A large outbreak of typhoid fever associated with a high rate of intestinal perforation in Kasese District, Uganda, 2008–2009. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1091–9.

Demczuk W, Finley R, Nadon C, Spencer A, Gilmour M, Ng L-K. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance, molecular and phage types of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi isolations. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(10):1414–26.

Bayram Y, Güdücüoğlu H, Otlu B, Aypak C, Gürsoy N, Uluç H, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and molecular typing of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi during a waterborne outbreak in Eastern Anatolia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2011;105(5):359–65.

Simango C. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Campylobacter species. South Afr J Epidemiol Infect. 2013;28(3):139–42.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank the nursing, clinical and laboratory staff of the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia, for facilitating the collection of the stool samples, especially Dr. Evans Mpabalwani and Mr. Kelly Mulenga of the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, and Mr. Joseph Ngulube of the Department of Pathology and Microbiology.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from Intra-ACP Academic Mobility Scheme of the Commission of the European Union Grant number: 2012–3166, the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) and the Tanzanian Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Management Training Programme (TFELTP). The funding agency did not any way influence the design of the study. Further funders did have access to the data and its management.

Availability of data and material

The data sets used in the analysis of this current study is readily available from the corresponding author and can be accessed upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

HC, JBM, SM, AA, JM, MIM conceived and designed the study; HC and GK contributed to sample collection; HC, GK and SM performed laboratory work; HC, MIM, JBM, SM, AA and GK analysed and interpreted the data; HC, GK, SM and MIM drafted the manuscript While MIM supervised the overall work; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Ethics approval and consent to publish

Consent to collect specimen from patients were obtained from the Parents/Guardian while permission to conduct the study was sought from the University Teaching Hospital Management in Lusaka, Zambia. Ethics clearance was sought from the Senate Research and Publication Committee in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania (Ref: MU/PGS/SAEC/Vol.XIV/) and the Excellence in Research Ethics and Science (ERES) IRB in Lusaka, Zambia (Ref: 2015-12-004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiyangi, H., Muma, J.B., Malama, S. et al. Identification and antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacterial enteropathogens from children aged 0–59 months at the University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia: a prospective cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 17, 117 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2232-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2232-0