Abstract

Background

Cefotaxime plays an important role in the treatment of patients with bacteremia due to Enterobacteriaceae, although cefotaxime resistance is reported to be increasing in association with extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) and AmpC β-lactamase (AmpC).

Methods

We conducted a case-control study in a Japanese university hospital between 2011 and 2012. We assessed the risk factors and clinical outcomes of bacteremia due to cefotaxime-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae (CTXNS-En) and analyzed the resistance mechanisms.

Results

Of 316 patients with Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia, 37 patients with bacteremia caused by CTXNS-En were matched to 74 patients who had bacteremia caused by cefotaxime-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae (CTXS-En). The most common CTXNS-En was Escherichia coli (43%), followed by Enterobacter spp. (24%) and Klebsiella spp. (22%). Independent risk factors for CTXNS-En bacteremia included previous infection or colonization of CTXNS-En, cardiac disease, the presence of intravascular catheter and prior surgery within 30 days. Patients with CTXNS-En bacteremia were less likely to receive appropriate empirical therapy and to achieve a complete response at 72 h than patients with CTXS-En bacteremia. Mortality was comparable between CTXNS-En and CTXS-En patients (5 vs. 3%). CTXNS-En isolates exhibited multidrug resistance but remained highly susceptible to amikacin and meropenem. CTX-M-type ESBLs accounted for 76% of the β-lactamase genes responsible for CTXNS E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates, followed by plasmid-mediated AmpC (12%). Chromosomal AmpC was responsible for 89% of CTXNS Enterobacter spp. isolates.

Conclusions

CTXNS-En isolates harboring ESBL and AmpC caused delays in appropriate therapy among bacteremic patients. Risk factors and antibiograms may improve the selection of appropriate therapy for CTXNS-En bacteremia. Prevalent mechanisms of resistance in CTXNS-En were ESBL and chromosomal AmpC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Third-generation cephalosporins, such as cefotaxime, form an important part of empirical antimicrobial therapy for infections caused by members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Third-generation cephalosporins can be a reasonable choice even for patients with nosocomial infections who have non-severe illness. However, a recent increase in the prevalence of third-generation cephalosporin-resistance has challenged the use of this therapy [1]. β-Lactamases have been recognized as the main cause of cephalosporin resistance among Enterobacteriaceae. The most common β-lactamases are extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), followed by AmpC β-lactamases [2].

When gram-negative bacteria is grown in blood culture, the type of positive blood culture bottle (aerobic or anaerobic) and the gram stain findings help us to estimate if the bacteria belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae family or are non-fermenting gram-negative bacteria. It is impossible to determine the exact genus or species without emerging rapid identification technologies, such as matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of flight mass spectrometry. Therefore, we usually determine a regimen of empiric therapy targeting Enterobacteriaceae, not specific species (e.g., E. coli). However, most studies regarding bacteremia due to third-generation cephalosporin-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae have focused on E. coli and K. pneumoniae [2–5]. A few studies have investigated Enterobacteriaceae as a group. Rottier et al. assessed risk factors for bacteremia by third-generation cephalosporin-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae [6], and two studies analyzed resistance mechanisms [7, 8]. Data from these bacteremias from Japan have not been reported. We conducted this study to determine the risk factors and clinical outcomes associated with bacteremia due to cefotaxime-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae (CTXNS-En). In addition, we elucidated the epidemiology of β-lactamases that confer resistance to CTXNS-En.

Methods

Setting and study design

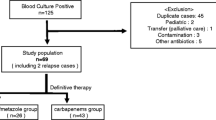

This study was conducted at Kyoto University Hospital, a tertiary care 1182-bed university hospital located in Japan. All patients with bacteremia due to CTXNS-En that occurred from January 2011 to December 2012 were enrolled in this study. Only the first episode of bacteremia was included for each patient. Case patients were defined as adult patients (≥18 years old) with Enterobacteriaceae isolates non-susceptible to cefotaxime grown in blood culture. Bacteremia with multiple pathogens was excluded. Control patients were matched in a 1:2 ratio to case patients according to the following algorithm: an adult patient with bacteremia due to cefotaxime-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae (CTXS-En) and the infective organism matched to that of the case patient (Fig. 1). If no matched organism was found, the organism that belonged to the same genus was selected. We did not perform routine screening for CTXNS-En colonization.

Definitions and variables

CTXNS-En isolates with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of >8 μg/mL were defined as CTXNS-En, and isolates with MICs ≤8 μg/mL were considered CTXS-En according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guideline (M100-S19) [9]. Each patient was classified as hospital-acquired, health care-associated, or community-acquired in accordance with the definitions of Friedman et al. [10]. Neutropenia was defined as an absolute neutrophil count below 500/mm3. Multidrug-resistant-Enterobacteriaceae (MDR-En) were defined as Enterobacteriaceae with resistance to 3 or more different classes of antibiotics [11].

Clinical characteristics included age, sex, underlying chronic disease, the Charlson weighted index of comorbidity [12], immunosuppressive therapy during the previous 30 days, antibiotic therapy during the previous 30 days, surgery during the previous 30 days, neutropenia, the presence of an intravenous catheter or any other artificial devices, the site of infection, the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [13], the site of acquisition, and the antimicrobial regimen and clinical outcomes, including mortality at 30 days.

Antimicrobial therapy was classified into initial empirical and definitive therapy, with the former defined as initial therapy provided within 72 h after bacteremia onset and the latter defined as therapy provided after the results of susceptibility tests had been reported. Antimicrobial therapy was considered appropriate when the isolate was reported as being susceptible to the agent by the clinical microbiology laboratory.

Clinical outcomes were evaluated daily until 7 days after starting antimicrobial therapy and were classified as follows: ‘complete response’ for patients who had resolved fever, leukocytosis and all signs of infection, ‘partial response’ for patients who had abatement of abnormalities in the above parameters without complete resolution and ‘failure’ for patients who had absence of abatement or who had deterioration in any clinical parameters or who died.

Microbiological analysis

Blood cultures were incubated on the BacT/Alert system (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) for 5 days. When growth was detected, the sample was subcultured and an isolated colony was used in the subsequent processes. All isolates and their antibiotic susceptibilities were determined using the MicroScan WalkAway 96 plus system (Siemens, Berlin, Germany). ESBL screening was performed according to the CLSI microdilution methodology, with modifications (cefpodoxime, ≥4 μg/mL; cefotaxime, ≥8 μg/mL; ceftazidime, ≥2 μg/mL; or aztreonam, ≥8 μg/mL). Quality control was performed using E. coli ATCC 25922, ATCC 35218 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 according to the CLSI document [9]. The confirmation of ESBL production was performed using cefotaxime-clavulanate and ceftazidime-clavulanate disks according to the CLSI guideline [9]. The cefoxitin-cloxacillin disk method was performed to test for chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase (c-AmpC) hyperproduction. Disks containing 30 μg of cefoxitin or 30 μg of cefoxitin plus 200 μg of cloxacillin were placed on Mueller-Hinton agar that was inoculated with each isolate, and the specimens were incubated at 37 °C for 16 to 18 h. A difference in the inhibition zones of cefoxitin and cloxacillin compared with cefoxitin alone of ≥4 mm was considered to be indicative of c-AmpC hyperproduction [14].

Bacterial DNA was isolated using a QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR analyses for the detection of TEM-, SHV-, and CTX-M-type β-lactamase genes were conducted as described elsewhere [15–19]. Plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase (p-AmpC) was detected using the multiplex PCR method [20] and was identified by sequencing. Isolates negative for ESBL and p-AmpC by PCR were then tested using the cefoxitin-cloxacillin disk method, as described above. Isolates non-susceptible to imipenem or meropenem (MIC > 1 μg/mL) were analysed to determine the presence of the carbapenemases using multiplex PCR [15]. Primers used for PCR and sequencing is provided in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of discrete variables were performed with Fisher’s exact test, and comparisons of continuous variables were performed using Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests. The time to a complete response within 7 days after starting antimicrobial therapy was analyzed using a Cox-hazard model. To determine the independent risk factors for CTXNS-En bacteremia and the time to a complete response, all variables with p-values of < 0.05 based on univariate analyses were subjected to further selection using forward stepwise logistic regression. We forced the inclusion of the Charlson index, the SOFA score and CTXNS-En bacteremia in the multivariate models. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using STATA software version 13 (StataCorporation College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Risk factors and clinical outcomes

A total of 316 non-duplicate patients with Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia were identified during the study period. Of these, 60 patients (19%) had infections caused by isolates that showed non-susceptibility to cefotaxime. Patients with polymicrobial bacteremia (n = 23) were excluded from the analysis, and 37 patients were analyzed as the CTXNS-En group. Of the remaining 256 patients with CTXS-En bacteremia, 32 patients with polymicrobial bacteremia were excluded, and 74 patients were selected as controls. Patients selection process and bacterial species were shown in Fig. 1.

The demographics of the patients and risk factors associated with bacteremia due to CTXNS-En and CTXS-En are listed in Table 1. The distributions for age and sex, severities of illness as measured by SOFA score, and the location of acquisition were comparable. Primary bacteremia, urinary tract infection, and intraabdominal infection were common sources of infection in both groups.

A risk factor analysis for the CTXNS-En revealed significant associations in the univariate analysis with a previous infection or colonization of CTXNS-En or MDR bacteria or fluoroquinolone-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, previous antibiotic use, duration of previous antibiotic therapy, cardiac disease, transplantation and prior surgery. In the multivariate analysis, previous infection or colonization of CTXNS-En (odds ratio [OR], 12.32; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.69–41.12), cardiac disease (OR, 5.00; CI, 1.64–15.28), the presence of an intravascular catheter (OR, 5.33; CI, 1.46–19.49) and prior surgery within 30 days (OR, 4.37; CI, 1.17–16.41) were independent risk factors for CTXNS-En bacteremia.

Complete response was achieved within 72 h in 4 (11%) and 23 (31%) of the patients in CTXNS-En and CTXS-En groups, respectively (Table 2). The CTXNS-En patients were less likely to receive appropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy than the CTXS-En patients. Mortality at 30 days was low in both the CTXNS-En and CTXS-En groups (5 and 3%, respectively).

Univariate analysis using the Cox-hazard model revealed that the variables independently associated with complete response were the presence of an intravascular catheter, the SOFA score, empirical carbapenem therapy and empirical third-generation cephalosporin therapy (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, the SOFA score (hazard ratio [HR], 0.88; CI, 0.80–0.96) and empirical third-generation cephalosporin therapy (HR, 2.13; CI, 1.30–3.50) were significant predictors of a complete response.

Microbiological results

The susceptibility testing results for the CTXNS-En and CTXS-En isolates of the case and control groups are shown in Table 4. Amikacin and meropenem were highly active, with greater than 90% of CTXNS-En isolates being susceptible to them. Susceptibility to cephalosporins, β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, fluoroquinolones and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was uncommon in CTXNS-En isolates compared with CTXS-En isolates, and CTXNS-En isolates more frequently exhibited multidrug resistance than CTXS-En isolates. Although one K. pneumoniae isolate and one K. oxytoca isolate had meropenem MICs of > 1 μg/mL, the multiplex PCR did not detect the presence of carbapenemases.

ESBL production was confirmed in 20 isolates among 37 CTXNS-En isolates, 19 of which harbored ESBL gene. All CTXS-En isolates were negative for ESBL confirmation test. The types of β-lactamase genes for the CTXNS-En isolates from the case group are shown in Table 5. The most prevalent β-lactamase gene harbored by E. coli was ESBL. In E. coli, bla CTX-M-14 was the most prevalent gene detected, followed by bla CTX-M-27. In the K. pneumoniae isolates, both ESBL and p-AmpC genes were dominant. bla DHA-1 was the only p-AmpC detected in K. pneumoniae. All but one isolate of Enterobacter spp. were considered to overproduce c-AmpC. The resistance mechanisms in P. penneri (n = 1) and S. marcescens (n = 2) were not determined.

Discussion

The prevalence of CTXNS-En varies across different geographic regions. A study from Spain revealed that 9.7, 12.5 and 29.1% of third-generation cephalosporin resistance in bloodstream infections were caused by E. coli, K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp., respectively [21]. In the SENTRY program study from the United States of America, the prevalence of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae that caused bacteremia was 6.4% [8]. In the Asia-Pacific region, approximately 10% of Enterobacteriaceae were phenotypically positive for ESBL production [22]. The prevalence of CTXNS-En in our study was consistent with these findings.

Previous antibiotic therapy, especially the use of cephalosporins, has been consistently recognized as a risk factor for third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia in many studies [2, 3, 6, 23]. Our study also demonstrated a significant association between previous antibiotic use and CTXNS-En bacteremia in the univariate analysis. Prior isolation of CTXNS-En also appears to be a potent risk factor [4, 6, 24], as shown in our study. These common risk factors found in both previous studies and our study may help to identify patients with CTXNS-En bacteremia. Although certain risk factors, including cardiovascular disease, the presence of intravascular catheters, and prior surgery within 30 days, suggested cardiovascular surgery as a risk factor for CTXNS-En bacteremia, prior cardiovascular surgery within 30 days was comparable between the CTXNS-En and CTXS-En groups. Patients with intravascular catheters are more likely to be hospitalized patients who receive complicated medical care and are more likely to acquire antibiotic-resistant pathogens. These results suggest that impaired patients who had undergone surgery had a high risk of acquiring CTXNS-En bacteremia.

Patients with bacteremia due to drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae have likely received inappropriate empirical therapy leading to worse mortality [2, 25, 26]. Although mortality was comparable between the CTXNS-En and CTXS-En groups in our study, empirical antimicrobial treatment was more frequently inappropriate among patients with CTXNS-En bacteremia, and a complete response was delayed in the CTXNS-En group compared with the CTXS-En group. Thus, we used a multivariate Cox-hazard model for time to complete response to further assess the association between CTXNS and delayed complete response. However, empirical third-generation cephalosporin therapy was associated with an earlier complete response. This result can be explained by the fact that patients who received third-generation cephalosporin as an empirical therapy had lower SOFA scores, indicating a less severe state of illness, compared with patients who received other empirical therapies (data shown in the footnote of Table 3). Other studies have also found that illness severity appears to be a more significant prognostic factor for clinical outcomes than appropriate antibiotic therapy [3, 27–29]. Nonetheless, the administration of appropriate antibiotic therapy is essential for the successful treatment of bacteremia, especially in patients with severe presentations.

In our study, CTXNS-En isolates had high rates of susceptibility to amikacin and meropenem. Treatments other than cefotaxime, such as amikacin or meropenem, should be considered for patients suspected of Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia with risk factors for CTXNS-En. Two isolates had meropenem MICs of greater than 1 μg/mL. Although carbapenems remain the drugs of choice for serious infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae, there is concern about the rise of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae [30]. Balancing the appropriateness of therapy and antibiotic overuse is essential. CTXNS-En isolates were likely to be MDR; co-resistance to fluoroquinolone is increasing in third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae [21, 31]. The use of antimicrobial agents will continue to create selection pressure that gives MDR-En the opportunity to become effective intestinal colonizers and provides opportunities for MDR-En to cause infections with limited therapeutic options [30]. Continuous monitoring of MDR-En and antimicrobial stewardship are recommended as important efforts to control MDR-En.

Ninety-four percent of E. coli and 43% of K. pneumoniae carried CTX-M-type ESBL genes, the majority of which encoded CTX-M-14. Whereas CTX-M-15 is the most widely distributed CTX-M-type ESBL worldwide [32], CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-27 are the most prevalent ESBL types of E. coli in Asia and Japan [22, 31]. Previous studies have suggested a low prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacter spp. and C. freundii in Japan [33, 34], and only one isolate of these organisms harbored the ESBL gene in our study. Whereas the predominance of CMY-2 has been described worldwide, including in Asia [22, 35], DHA-1 is the most dominant p-AmpC in K. pneumoniae isolates in Japan and Asia [22, 36], which is consistent with the findings of our study. Many Enterobacteriaceae species, such as Enterobacter spp., Citrobacter spp. and S. marcescens, encode c-AmpC, which can be expressed at high levels by either induction or selection for derepressed mutants in the presence of β-lactam antibiotics [35]. All of the patients who had bacteremia with c-AmpC-overproducing CTXNS-En were exposed to β-lactam within 30 days. The resistance mechanism was not determined in S. marcescens and P. penneri. P. penneri harbors a class A β-lactamase, HugA, which confers third-generation cephalosporin-resistance and is regulated by an equivalent of the amp system, a regulation system of c-AmpC, although we did not assess HugA β-lactamase [37].

There were some potential limitations to this study. First, the sample size was small, making type II error a concern. Second, our results were from a single center, and the prevalence of CTXNS-En isolates likely varies across institutions, making it difficult to generalize the prevalence of CTXNS-En in our patients to those at other institutions. Third, we used the old CLSI breakpoint for cefotaxime because the treatment decision was made based on the old CLSI breakpoint. The revised CLSI guideline in 2010 adopted a lower breakpoint for cefotaxime (≤1 μg/ml) [38], which may limit the generalizability of this study.

Conclusions

CTXNS-En bacteremia is associated with inappropriate empirical therapy, and the frequent occurrence of a delay in appropriate therapy likely contributes to inferior clinical responses. CTXNS-En isolates were likely to be MDR. Treatments other than cefotaxime, such as amikacin or meropenem, should be considered for patients suspected of Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia with risk factors for CTXNS-En or severe illness. However, cefotaxime may remain the treatment of choice for patients without these risk factors. Acquired β-lactamases, especially CTX-M type ESBL, were common in E. coli and Klebsiella spp., whereas hyperactivation of intrinsic resistance was common in Enterobacter spp.

Abbreviations

- AmpC:

-

AmpC β-lactamase

- c-AmpC:

-

Chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CTXNS-En:

-

Cefotaxime-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae

- CTXS-En:

-

Cefotaxime-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae

- ESBL:

-

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- MDR:

-

Multidrug-resistant

- MDR-En:

-

MDR-Enterobacteriaceae

- MICs:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentrations

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- p-AmpC:

-

Plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

References

Pitout JD. Multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae: new threat of an old problem. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2008;6:657–69.

Courpon-Claudinon A, Lefort A, Panhard X, Clermont O, Dornic Q, Fantin B, et al. Bacteraemia caused by third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli in France: prevalence, molecular epidemiology and clinical features. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:557–65.

Rodriguez-Bano J, Picon E, Gijon P, Hernandez JR, Cisneros JM, Pena C, et al. Risk factors and prognosis of nosocomial bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1726–31.

Nguyen ML, Toye B, Kanji S, Zvonar R. Risk factors for and outcomes of bacteremia caused by extended-spectrum ß-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella Species at a Canadian Tertiary Care Hospital. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68:136–43.

Gürntke S, Kohler C, Steinmetz I, Pfeifer Y, Eller C, Gastmeier P, et al. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae from bloodstream infections and risk factors for mortality. J Infect Chemother. 2014;20:817–9.

Rottier WC, Bamberg YR, Dorigo-Zetsma JW, van der Linden PD, Ammerlaan HS, Bonten MJ. Predictive value of prior colonization and antibiotic use for third-generation cephalosporin-resistant enterobacteriaceae bacteremia in patients with sepsis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1622–30.

Vlieghe ER, Huang TD, Phe T, Bogaerts P, Berhin C, De Smet B, et al. Prevalence and distribution of beta-lactamase coding genes in third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from bloodstream infections in Cambodia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:1223–9.

Castanheira M, Farrell SE, Deshpande LM, Mendes RE, Jones RN. Prevalence of beta-lactamase-encoding genes among Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia isolates collected in 26 U.S. hospitals: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2010). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3012–20.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; nineteenth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S19. Wayne: CLSI; 2009.

Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, McGarry SA, Trivette SL, Briggs JP, et al. Health care--associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:791–7.

Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Vincent JL, de Mendonca A, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter PM, et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1793–800.

Polsfuss S, Bloemberg GV, Giger J, Meyer V, Böttger EC, Hombach M. Practical approach for reliable detection of AmpC beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2798–803.

Dallenne C, Da Costa A, Decré D, Favier C, Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:490–5.

Xu L, Ensor V, Gossain S, Nye K, Hawkey P. Rapid and simple detection of blaCTX-M genes by multiplex PCR assay. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:1183–7.

Briñas L, Zarazaga M, Sáenz Y, Ruiz-Larrea F, Torres C. Beta-lactamases in ampicillin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from foods, humans, and healthy animals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3156–63.

Yagi T, Kurokawa H, Shibata N, Shibayama K, Arakawa Y. A preliminary survey of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in Japan. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;184:53–6.

Saladin M, Cao VT, Lambert T, Donay JL, Herrmann JL, Ould-Hocine Z, et al. Diversity of CTX-M beta-lactamases and their promoter regions from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in three Parisian hospitals. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;209:161–8.

Pérez-Pérez FJ, Hanson ND. Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamase genes in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2153–62.

Asensio A, Alvarez-Espejo T, Fernandez-Crehuet J, Ramos A, Vaque-Rafart J, Bishopberger C, et al. Trends in yearly prevalence of third-generation cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections and antimicrobial use in Spanish hospitals, Spain, 1999 to 2010. Euro Surveill. 2011;16:12-20.

Sheng WH, Badal RE, Hsueh PR, Program S. Distribution of extended-spectrum β-lactamases, AmpC β-lactamases, and carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae isolates causing intra-abdominal infections in the Asia-Pacific region: results of the study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2981–8.

Chopra T, Marchaim D, Johnson PC, Chalana IK, Tamam Z, Mohammed M, et al. Risk factors for bloodstream infection caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: A focus on antimicrobials including cefepime. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:719–23.

Denis B, Lafaurie M, Donay JL, Fontaine JP, Oksenhendler E, Raffoux E, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and impact on clinical outcome of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli bacteraemia: a five-year study. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;39:1–6.

Tumbarello M, Sanguinetti M, Montuori E, Trecarichi EM, Posteraro B, Fiori B, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: importance of inadequate initial antimicrobial treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1987–94.

Van Aken S, Lund N, Ahl J, Odenholt I, Tham J. Risk factors, outcome and impact of empirical antimicrobial treatment in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli bacteraemia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46:753–62.

Kim BN, Lee SO, Choi SH, Kim NJ, Woo JH, Ryu J, et al. Outcome of antibiotic therapy for third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative bacteraemia: an analysis of 249 cases caused by Citrobacter, Enterobacter and Serratia species. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;22:106–11.

Thom KA, Schweizer ML, Osih RB, McGregor JC, Furuno JP, Perencevich EN, et al. Impact of empiric antimicrobial therapy on outcomes in patients with Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:116.

Falcone M, Vena A, Mezzatesta ML, Gona F, Caio C, Goldoni P, et al. Role of empirical and targeted therapy in hospitalized patients with bloodstream infections caused by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Ann Ig. 2014;26:293–304.

Vasoo S, Barreto JN, Tosh PK. Emerging issues in gram-negative bacterial resistance: an update for the practicing clinician. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:395–403.

Matsumura Y, Yamamoto M, Higuchi T, Komori T, Tsuboi F, Hayashi A, et al. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and spread of the ST131 clone among extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing E. coli in Japan. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:158–62.

Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Bertrand X, Madec JY. Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:543–74.

Kanamori H, Yano H, Hirakata Y, Hirotani A, Arai K, Endo S, et al. Molecular characteristics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and qnr determinants in Enterobacter species from Japan. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37967.

Kanamori H, Yano H, Hirakata Y, Endo S, Arai K, Ogawa M, et al. High prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and qnr determinants in Citrobacter species from Japan: dissemination of CTX-M-2. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2255–62.

Jacoby GA. AmpC beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:161–82.

Yamasaki K, Komatsu M, Abe N, Fukuda S, Miyamoto Y, Higuchi T, et al. Laboratory surveillance for prospective plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases in the Kinki region of Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3267–73.

Liassine N, Madec S, Ninet B, Metral C, Fouchereau-Peron M, Labia R, et al. Postneurosurgical meningitis due to Proteus penneri with selection of a ceftriaxone-resistant isolate: analysis of chromosomal class A beta-lactamase HugA and its LysR-type regulatory protein HugR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:216–9.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twentieth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S20. Wayne: CLSI; 2010.

Funding

No funding was received to perform this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

TN conceived the study, participated in its design, reviewed the medical records, performed the laboratory work, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. YM participated in the design of the study, coordination, and manuscript preparation. MY, MN, ST and SI participated in manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used retrospective chart reviews and bacterial isolates collected in clinical settings, so that this research involves no more than minimal risk. The Ethics Committee of the Kyoto University Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine approved this study (E-2103) waived the need for obtaining informed consent from each patient.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Primers used for PCR and sequence. (DOCX 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Noguchi, T., Matsumura, Y., Yamamoto, M. et al. Clinical and microbiologic characteristics of cefotaxime-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: a case control study. BMC Infect Dis 17, 44 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-2150-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-2150-6