Abstract

Background

The performance of recommended control measures is necessary for quick and uniform infectious disease outbreak control. To assess whether these procedures are performed, a valid set of quality indicators (QIs) is required. The goal of this study was to select a set of key recommendations that can be systematically translated into QIs to measure the quality of infectious disease outbreak response from the perspective of disaster emergency responders and infectious disease control professionals.

Methods

Applying the Rand modified Delphi procedure, the following steps were taken to systematically select a set of key recommendations: extraction of recommendations from relevant literature; appraisal of the recommendations in terms of relevance through questionnaires to experts; expert meeting to discuss recommendations; prioritization of recommendations through a second questionnaire; and final expert meeting to approve the selected set. Infectious disease physicians and nurses, policymakers and communication experts participated in the expert group (n = 48).

Results

In total, 54 national and international publications were systematically searched for recommendations, yielding over 200 recommendations. The Rand modified Delphi procedure resulted in a set of 65 key recommendations. The key recommendations were categorized into 10 domains describing the whole response pathway from outbreak recognition to aftercare.

Conclusion

This study provides a set of key recommendations that represents ‘good quality of response to an infectious disease outbreak’. These key recommendations can be systematically translated into QIs. Organizations and professionals involved in outbreak control can use these QIs to monitor the quality of response to infectious disease outbreaks and to assess in which domains improvement is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infectious disease outbreaks are a global threat to public health that can have a high economical and societal impact [1,2]. During an outbreak, recommended control measures need to be timely and uniformly performed to curb the spread of pathogens and, ultimately, to reduce the number of persons becoming infected [3].

Numerous documents -from various countries or regions addressing various types of outbreaks- describe such recommended or ‘good quality’ response to infectious disease outbreaks. Unfortunately, publication and dissemination of scripts, guidelines and scientific advice does not guarantee good quality outbreak response [4-6]. Evaluations of recent crises show large variation in the implementation of crisis advice and thus in the quality of outbreak response. A Dutch study examining the response to the Q-fever outbreak showed large regional variance in the implementation of the nationally advised measures [7]. Similarly, evaluation of the control measures during the early stages of the lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) outbreak in the various EU countries showed great differences between countries with respect to case definitions, laboratory testing and antimicrobial drug treatment [8]. A study examining the causes of differences in the implementation of crisis advice showed that among others, the various categories of professionals involved in outbreak control lacked clearly defined measures to monitor the execution of ‘key actions’ [9].

Quality indicators (QIs) can be used to gain insight into the quality of response and, even more importantly, they can be used to measure the effects of interventions aimed at improving response [10]. In this manner, QIs provide a tool to systematically monitor response quality. Two studies developed QIs for infectious disease outbreak response describing the major domains of outbreak response [11,12]. Both studies lack transparency and reproducibility because they do not provide insight into among others; the selected literature, selected experts and the definition of consensus. It is important that QIs are developed in a systematic and transparent way [10,13,14], which to our knowledge has not been done for infectious disease outbreaks.

The goal of this study was therefore to select a set of key recommendations that can be systematically translated into QIs to measure the quality of infectious disease outbreak response from the perspective of disaster emergency responders and infectious disease control professionals (ID-control professionals) using a valid development procedure. We aimed to develop a generic set of key recommendations that can be used to measure the quality of outbreak response, irrespective of the causative pathogen.

Methods

We used the systematic RAND modified Delphi method to develop and select -in a multistep approach (see Step1 through 5 below)- a set of key recommendations representing good quality infectious disease outbreak response [15]. In this iterative method the individual opinion of experts is aggregated into group consensus. Recommendations for infectious disease outbreak response were extracted from the literature, and presented to a multidisciplinary expert panel. The panel achieved consensus on a set of key recommendations during two questionnaire rounds and two face-to face consensus meetings. Formal ethical approval from a medical ethical committee was not required for this research in the Netherlands since it does not entail subjecting participants to medical treatment or imposing specific rules of conduct on participants. All the experts consented to participate in the study and were aware that their responses would be used for research purposes.

Step 1 – Literature search and extraction of recommendations

We performed a literature search using the Medline database to review the international literature for information about quality indicators and recommendations for good quality response to an infectious disease outbreak from the year 2007 (search executed 4th week of February 2012). Table 1 shows the search strategy in which we combined the gold standard search strategy of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group to identify quality improvement studies and combined these (http://epoc.cochrane.org/) with terms on outbreaks and performance measurement. Two researchers (EB and AT) independently examined title and abstract of the publications to include any publication (for example outbreak reports, evaluations, health services research studies, guidelines) potentially describing recommendations for ID-control professionals and disaster emergency responders. Exclusion criteria were: publications that were not about infectious disease outbreaks (non outbreak setting or no acute outbreak like HIV), publications describing recommendations for a hospital setting, publications that were setting/region or patient specific, and publications that described simulations or mathematical models of outbreaks.

Next, we collected grey literature, i.e. Dutch documents on good quality response including national guidance, national outbreak advice, contracts between health care organizations and disaster care plans. We also included national evaluations of recent infectious disease crises such as Q-fever and the 2009 flu pandemic. The inclusion of grey literature was made on the basis of recommendations from national specialists on infectious disease preparedness- and control who were asked to judge appropriateness.

Two researchers (EB and MHi) performed the extraction of recommendations independently on a sample consisting of 25% of all selected sources (literature review and grey literature). The researchers extracted good quality response recommendations from the selected literature. Discrepancies between the two researchers were discussed until consensus was reached. After reaching consensus on this 25% sample, one researcher continued to extract recommendations from the remaining selected literature (EB). The two researchers examined the total set of recommendations to remove identical recommendations.

All recommendations were discussed with the main researchers involved in this study (MHu, JH, AT, EB) in two meetings. In these meetings we selected in consensus and while applying the inclusion criteria, existing generic recommendations or aggregated pathogen and disease specific recommendations, which were subsequently presented to the participants in the expert panels during the next stages.

Step 2 – First questionnaire round

The consensus procedure took place between September 2012 and May 2013. We approached all 25 public health regions from the Netherlands by e-mail and invited public health infectious disease experts from their region to participate in the expert group. Our expert panels consisted of 48 Dutch experts in public health (28 ID-control professionals and 20 disaster emergency responders) who all had experience in the preparedness and/or control of an infectious disease outbreak. All regions were represented.

Two digital Limesurvey (a digital open source survey application) questionnaires were composed, one for the ID-control professionals and one for the disaster emergency responders. In this process, recommendations were assigned to the responsible organization in the Netherlands: logistical support recommendations were presented to disaster emergency responders and infectious disease control recommendations were presented to ID-control professionals. In the Netherlands, the disaster emergency responder tasks lay with charge of logistical support of outbreak control while the coordination of outbreak measures is a responsibility of the ID-control experts. This, of course, can be different in other countries.

Both expert groups followed a parallel, methodologically identical path: each expert group assessed the recommendations regarding their expertise on relevance. Relevance was graded by the experts in response to the following question; “To what extent do you consider this recommendation as a relevant element for measuring the quality of infectious disease outbreak response?” on a 9-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 9 = totally agree). Experts could comment on recommendations and could add recommendations. Recommendations were accepted or further processed based on the RAND/University of California at Los Angeles agreement criteria [15]. Relevance scores were calculated for each item. If the recommendation had a median of 8 or 9 and >70% of the experts scored in the top tertile, then the recommendation was marked as “accepted”. If the recommendation had a median <8 and <70% scored in the top tertile, then the recommendation was marked as “not accepted” and was excluded. If the recommendation had a median <8 and >70% of the experts scored in the top tertile or the median was 8 or 9 and <70% of the experts scored in the top tertile, then the recommendation was marked as “to be discussed”.

In the second part of the questionnaire we checked whether we assigned recommendations to the correct responsible organization (disaster emergency responders or ID-control experts). If more than 33% of the responders questioned the attribution of responsibility for the action to a certain party, then the recommendation was presented to the responsible organization in the second questionnaire round.

Step 3 – Consensus meeting

Both expert groups were invited for a separate face-to-face consensus meeting in October 2012. The results of the analysis of the questionnaires were sent to the experts in advance of the consensus meeting. During the meeting, the expert panels could comment on recommendations with the label “to be discussed”. As a result, the discussed recommendations were found to be not relevant or were modified and found relevant.

Step 4 – Second questionnaire round

In step 4, two responsible organization specific questionnaires were composed of all recommendations. To categorize the recommendations, we combined two frameworks which incorporate the main domains of emergency response [16,17]. The recommendations were categorized into 35 categories (25 for ID-control experts and 10 for disaster emergency responders) which described each step in the process of infectious disease outbreak response. These 35 categories or subdomains represented 10 main domains: “Scale of the outbreak and epidemiology”, “Control measures”, “Diagnostics”, “Logistic support”, “Aftercare and conclusion”, “Communication”, “Logistics”, “Upscaling”, “Coordination of the chain of outbreak control” and “Continuity of care”.

Corrections on the assigned responsible organization based on the first questionnaire were processed in this second questionnaire. Doubles were removed if there was too much resemblance of the recommendations within one category. If a number of recommendations represented the same recommendation, but for different patient groups (for example, confirmed case, contact of cases) the recommendations were merged. We asked both expert groups to prioritize the most important recommendation per category, and we calculated the percentage of experts that selected a recommendation. If more than 15 percent of the experts selected a recommendation, the recommendation was considered prioritized. Each group only prioritized recommendations regarding their own expertise.

Step 5 – Second consensus meeting

In a final, combined face-to-face expert meeting the experts were presented the combined selected sets of quality indicators from step 4. Experts were asked to judge the completeness of the selected recommendations. As a result, recommendations were textually modified, merged or deleted.

Results

Step 1 – Literature search and selection of recommendations

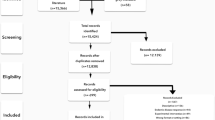

The Medline search for international literature regarding quality indicators and recommendations for good quality response to an infectious disease outbreak resulted in 151 unique publications (two identical publications were removed), see Figure 1. Based on title and abstract, 106 of these international publications were excluded while applying exclusion criteria. The remaining 47 publications [18-64] were read full text. From 11 [24,26,27,33,37,38,48,51,58,60,64] out of these 47 articles, we extracted 35 recommendations. The national specialists on infectious disease preparedness- and control plans provided 43 grey literature documents (see Additional file 1), from which we extracted 1057 recommendations. In total, we extracted 1092 recommendations from both the international and the grey literature.

After removal of doubles and of recommendations that were not executed by ID-control professionals and disaster emergency responders, 656 recommendations remained of which 35 were extracted from the international literature. These recommendations were discussed with all researchers involved in this study to make the recommendations generic so that they apply to all outbreaks irrespective of the nature of the causative pathogen and removed doubles while applying the inclusion criteria. This resulted in 226 recommendations (155 for ID-control professionals and 71 for disaster emergency responders). Figure 2 displays the results from the consensus procedure.

Step 2 – First questionnaire round

Forty-four experts returned the first questionnaire (response rate 92%) containing the 226 recommendations resulting from step 1. After applying the RAND/University of California at Los Angeles agreement criteria, the first consensus round resulted in 138 “accepted” recommendations. Thirty-eight recommendations were found “not accepted”, and therefore excluded. Thirty-one recommendations were marked as “to be further processed in the second questionnaire”.

Both the “accepted” recommendations and the “to be further processed in the second questionnaire” recommendations (N = 169) were subsequently included in the second questionnaire (discussed further in step 4). Nineteen recommendations were marked “ to be discussed ”, meaning that the experts did not reach consensus on the relevance or non-relevance of the items. These recommendations were further assessed in step 3.

Step 3 – Consensus meeting

In the third step, the expert panels could comment on recommendations with the label “to be discussed” in a consensus meeting. Fourteen ID-control professionals (14 out of 28) and 16 disaster emergency responders (16 out of 20) attended the consensus meeting. The ID-control professionals discussed nine recommendations, of which one was found not relevant, seven were found relevant after textual modification and one was found relevant without modification.

The disaster emergency responders discussed ten recommendations of which two were found not relevant. Two recommendations were combined into one and as a result, seven recommendations were found relevant after textual modification.

In total fifteen recommendations were accepted for further assessment.

Step 4 - Second questionnaire round

Recommendations were combined into one if the recommendations represented the same action but a different target group (for instance management of suspected case, case, confirmed case). This resulted in a reduction from 184 to 160 recommendations. The prioritization questionnaire consisted of 160 recommendations, of which 31 had to be appraised by both the disaster emergency responders and the ID-control professionals as in practice both could be made responsible for performing the recommended activity.

Forty experts returned the second questionnaire (response rate 88.9%). As a result, the ID-control professionals selected 55 recommendations, the disaster emergency responders 21. In some cases both types of experts prioritized the same recommendation. Deleting those resulted in 69 unique recommendations from both expert groups.

Step 5 – Second consensus meeting

In the final consensus meeting, both expert panels were merged. Seventeen experts (17 out of 48) attended the consensus meeting. The group discussed the 69 recommendations resulting from step 4. Three recommendations were deleted, 1 newly added and 4 combined into 2. This resulted in 65 recommendations divided among 10 main domains (Table 2): Scale of the outbreak and epidemiology (n = 2), Control measures (n = 22), Diagnostics (n = 9), Logistical support (n = 4), Aftercare and conclusion (n = 2), Communication (n = 5), Logistics (n = 6), Upscaling (n = 5), Coordination of the chain of outbreak control (n = 6) Continuity of care (n = 4).

Discussion

In this study, we selected a set of 65 key recommendations describing good quality of infectious disease outbreak response, based on scientific and grey literature, while applying the systematic Rand modified Delphi procedure. We selected key recommendations for the broad range of tasks in infectious disease outbreak response, from “control measures” and “diagnostics” to processes such as “coordination of the chain of outbreak control”. These recommendations can be systematically translated into a set of quality indicators. This QI set is a valuable tool to monitor the quality of response to infectious disease outbreak irrespective of the pathogen, and to assess in which domains improvement is needed. To our knowledge, no generic QIs have been systematically developed to measure the quality of infectious disease outbreak response from the perspective of disaster emergency responders and ID-control professionals describing the whole process of infectious disease outbreak response.

Two studies previously developed QIs applicable to some specific components of outbreak response [11,12]. One study focused on organizational aspects like vaccine availability, communication and reporting [11], while the other study focused on the correct and timely detection of the first cases and the initiation of prophylaxis, education and advice to healthcare workers [12]. Although there is some resemblance between the domains selected in these two studies and our study, our key recommendations are more detailed and specific, which is crucial for a valid and reliable assessment of quality but also for selecting targets for improvement.

Our study has some strengths and limitations. The strength is that our panels consisted of 26 and 18 experts with ample experience in outbreak control, ensuring optimal face validity of the key recommendations. Literature describes that 7–15 experts per panel are needed in order to develop a reliable set of indicators, [15]. The experts brought expertise from various fields such as: infectious disease control, policy making, public health administration, contingency planning, public health nursing, and had been involved in regional and national meetings regarding infectious disease control. Diversity of expert panel members leads to consideration of different perspectives and a wider range of alternatives [65].

Preferably, key recommendations are selected combining evidence- and consensus based recommendations, with a strong preference for evidence based [14]. A limitation of our study is that, from the 656 recommendations which served as a basis for the first questionnaire round, only 35 were extracted from the international literature. In addition, the recommendations are merely practice and expert opinion based. Expert opinion is considered to be the lowest degree of evidence [66]. This is in line with Yeager et al., who studied the literature and concluded that “the public health emergency preparedness literature is dominated by nonempirical studies”. They also describe how only 15 percent of scientific literature on infectious disease outbreaks concerns the response to outbreaks [67]. Although this explains the lack of evidence based recommendations in our study, at the same time it stresses the importance of building a knowledge base for ‘good quality’ response to infectious disease outbreaks. Our set of key could be the starting point for such methodologically sound empirical studies. Another limitation of our study is that our results are, for pragmatic reasons, based on judgments by Dutch experts and partly on Dutch grey literature which may reduce transferability to other countries. To reduce this risk as much as possible, we used a large group of experienced experts with various backgrounds. In addition, a considerable part of the Dutch grey literature is based on documents issued by supranational institutions (e.g. the WHO checklist, ECDC or CDC guidelines). We therefore assume that our key recommendations describe essential elements of outbreak response and will have an added value in improving efforts to deliver high quality response to outbreaks. These key recommendations are formulated in such a way that they allow for adaptation to fit the specific organizational structure of different countries. Most countries have their own national guidelines. European countries lacking national guidelines are very likely to use ECDC guidance instead (such as the RAGIDA guidelines or guidance disseminated through Rapid Risk Assessments).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides systematically selected key recommendations for good quality of infectious disease outbreak response. These recommendations can be systematically translated into QI to measure the quality of infectious disease outbreak response and to assess in which domains improvement is needed. Their consequent application will provide public health organizations with knowledge on where improvement of outbreak response is needed and how to prioritise the efforts to achieve optimal and uniform outbreak control, in order to be prepared for the next crisis.

The most successful indicators for quality improvement are indicators that are measurable, have potential for feasible improvement, are capable of detecting differences in scores and therefore of discriminating between organizations and are applicable to a large part of the population [14]. At this moment, we are performing a study to test the measurability of our set of key recommendations in practice.

References

Brooke RJ, Van Lier A, Donker GA, Van Der Hoek W, Kretzschmar ME. Comparing the impact of two concurrent infectious disease outbreaks on The Netherlands population, 2009, using disability-adjusted life years. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(11):2412–21.

Smith RD. Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management. Soc Science Med (1982). 2006;63(12):3113–23.

WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response: A WHO Guidance Document. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45.

Schuster MA, McGlynn EA, Brook RH. How good is the quality of health care in the United States? Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):517. –563, 509.

Grol R, Wensing M. Implementatie Effectieve verbetering van de patiëntenzorg. Vierde, herziene druk edn. Amsterdam: Reed Business; 2011.

Isken LD. Eindrapport evaluatie Q-koortsuitbraak in Noord-Brabant 2007. 2009.

Timen A, Hulscher ME, Vos D, van de Laar MJ, Fenton KA, Van Steenbergen JE, et al. Control measures used during lymphogranuloma venereum outbreak, Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(4):573–8.

Timen A, Hulscher ME, Rust L, Van Steenbergen JE, Akkermans RP, Grol RP, et al. Barriers to implementing infection prevention and control guidelines during crises: experiences of health care professionals. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(9):726–33.

Lawrence M, Olesen F. Indicators of Quality in Health Care. Eur J Gen Pract. 1997;3(3):103–8.

Torner N, Carnicer-Pont D, Castilla J, Cayla J, Godoy P, Dominguez A. Auditing the management of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks: the need for a tool. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e15699.

Potter MA, Sweeney P, Iuliano AD, Allswede MP. Performance indicators for response to selected infectious disease outbreaks: a review of the published record. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(5):510–8.

Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20476.

Kotter T, Blozik E, Scherer M. Methods for the guideline-based development of quality indicators–a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2012;7:21.

Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aquilar MD, Burnand B, LaCalle JR, Lazaro P, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method user’s manual. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation; 2001.

Gibson PJ, Theadore F, Jellison JB. The common ground preparedness framework: a comprehensive description of public health emergency preparedness. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(4):633–42.

Van Ouwerkerk IMS, Isken LD, Timen A. Een kader voor het evalueren van infectieziekteuitbraken. Infectieziekte Bulletin. 2009;20(3):95–8.

Cherifi S, Reynders M, Theunissen C. Hospital preparedness and clinical description of the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in a Belgian tertiary hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77(2):118–22.

Manigat R, Wallet F, Andre JC. From past to better public health programme planning for possible future global threats: case studies applied to infection control. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2010;46(3):228–35.

McVernon J, Mason K, Petrony S, Nathan P, LaMontagne AD, Bentley R, et al. Recommendations for and compliance with social restrictions during implementation of school closures in the early phase of the influenza A (H1N1) 2009 outbreak in Melbourne, Australia. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:257.

Panda B, Stiller R, Panda A. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and factors for lacking compliance with current CDC guidelines. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(3):402–6.

Inoue Y, Matsui K. Physicians’ recommendations to their patients concerning a novel pandemic vaccine: a cross-sectional survey of the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic in Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2011;16(5):320–6.

Sorbe A, Chazel M, Gay E, Haenni M, Madec JY, Hendrikx P. A simplified method of performance indicators development for epidemiological surveillance networks–application to the RESAPATH surveillance network. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2011;59(3):149–58.

Steelfisher GK, Blendon RJ, Bekheit MM, Mitchell EW, Williams J, Lubell K, et al. Novel pandemic A (H1N1) influenza vaccination among pregnant women: motivators and barriers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6 Suppl 1):S116–23.

Dehecq JS, Baville M, Margueron T, Mussard R, Filleul L. The reemergence of the Chikungunya virus in Reunion Island on 2010: evolution of the mosquito control practices. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2011;104(2):153–60.

Mitchell T, Dee DL, Phares CR, Lipman HB, Gould LH, Kutty P, et al. Non-pharmaceutical interventions during an outbreak of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection at a large public university, April-May 2009. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52 Suppl 1:S138–45.

Tsalik EL, Cunningham CK, Cunningham HM, Lopez-Marti MG, Sangvai DG, Purdy WK, et al. An Infection Control Program for a 2009 influenza A H1N1 outbreak in a university-based summer camp. J Am Coll Health. 2011;59(5):419–26.

Izadi M, Buckeridge DL. Optimizing the response to surveillance alerts in automated surveillance systems. Stat Med. 2011;30(5):442–54.

Kavanagh AM, Bentley RJ, Mason KE, McVernon J, Petrony S, Fielding J, et al. Sources, perceived usefulness and understanding of information disseminated to families who entered home quarantine during the H1N1 pandemic in Victoria, Australia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:2.

Schaade L, Reuss A, Haas W, Krause G. Pandemic preparedness planning. What did we learn from the influenza pandemic (H1N1) 2009? Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2010;53(12):1277–82.

Nicoll A. Pandemic risk prevention in European countries: role of the ECDC in preparing for pandemics. Development and experience with a national self-assessment procedure, 2005–2008. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2010;53(12):1267–75.

Lanari M, Capretti MG, Decembrino L, Natale F, Pedicino R, Pugni L, et al. Focus on pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza (swine flu). Minerva Pediatr. 2010;62(3 Suppl 1):39–40.

Ward KA, Armstrong P, McAnulty JM, Iwasenko JM, Dwyer DE. Outbreaks of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 and seasonal influenza A (H3N2) on cruise ship. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(11):1731–7.

Goodacre S, Challen K, Wilson R, Campbell M. Evaluation of triage methods used to select patients with suspected pandemic influenza for hospital admission: cohort study. Health Technol Assess (Winchester England). 2010;14(46):173–236.

Martin R, Conseil A, Longstaff A, Kodo J, Siegert J, Duguet AM, et al. Pandemic influenza control in Europe and the constraints resulting from incoherent public health laws. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:532.

Low CL, Chan PP, Cutter JL, Foong BH, James L, Ooi PL. International health regulations: lessons from the influenza pandemic in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2010;39(4):325–8.

Tay J, Ng YF, Cutter JL, James L. Influenza A (H1N1–2009) pandemic in Singapore–public health control measures implemented and lessons learnt. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39(4):313–24.

Poalillo FE, Geiling J, Jimenez EJ. Healthcare personnel and nosocomial transmission of pandemic 2009 influenza. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):e98–e102.

Vivancos R, Sundkvist T, Barker D, Burton J, Nair P. Effect of exclusion policy on the control of outbreaks of suspected viral gastroenteritis: Analysis of outbreak investigations in care homes. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(2):139–43.

Harrison JP, Bukhari SZ, Harrison RA. Medical response planning for pandemic flu. Health Care Manag. 2010;29(1):11–21.

Smith EC, Burkle Jr FM, Holman PF, Dunlop JM, Archer FL. Lessons from the front lines: the prehospital experience of the 2009 novel H1N1 outbreak in Victoria, Australia. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3 Suppl 2:S154–9.

Bouye K, Truman BI, Hutchins S, Richard R, Brown C, Guillory JA, et al. Pandemic influenza preparedness and response among public-housing residents, single-parent families, and low-income populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99 Suppl 2:S287–93.

Seale H, McLaws ML, Heywood AE, Ward KF, Lowbridge CP, Van D, et al. The community’s attitude towards swine flu and pandemic influenza. Med J Aust. 2009;191(5):267–9.

Rao S, Scattolini de Gier N, Caram LB, Frederick J, Moorefield M, Woods CW. Adherence to self-quarantine recommendations during an outbreak of norovirus infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(9):896–9.

O’Brien C, Selod S, Lamb KV. A national initiative to train long-term care staff for disaster response and recovery. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2009;15(2 Suppl):S20–4.

Davey VJ, Glass RJ, Min HJ, Beyeler WE, Glass LM. Effective, robust design of community mitigation for pandemic influenza: a systematic examination of proposed US guidance. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2606.

Kivi M, Koedijk FD, van der Sande M, van de Laar MJ. Evaluation prompting transition from enhanced to routine surveillance of lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) in the Netherlands. Euro surveillance. 2008;13(14):8087.

Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Bresee JS. Pandemic influenza and pregnant women. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(1):95–100.

Cavey AM, Spector JM, Ehrhardt D, Kittle T, McNeill M, Greenough PG, et al. Mississippi’s infectious disease hotline: a surveillance and education model for future disasters. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(1):11–7.

Brandeau ML, Hutton DW, Owens DK, Bravata DM. Planning the bioterrorism response supply chain: learn and live. Am J Disaster Med. 2007;2(5):231–47.

Burkle Jr FM, Hsu EB, Loehr M, Christian MD, Markenson D, Rubinson L, et al. Definition and functions of health unified command and emergency operations centers for large-scale bioevent disasters within the existing ICS. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2007;1(2):135–41.

Terhakopian A, Benedek DM. Hospital disaster preparedness: mental and behavioral health interventions for infectious disease outbreaks and bioterrorism incidents. Am J Disaster Med. 2007;2(1):43–50.

Muto CA, Blank MK, Marsh JW, Vergis EN, O’Leary MM, Shutt KA, et al. Control of an outbreak of infection with the hypervirulent Clostridium difficile BI strain in a university hospital using a comprehensive “bundle” approach. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(10):1266–73.

Shigayeva A, Green K, Raboud JM, Henry B, Simor AE, Vearncombe M, et al. Factors associated with critical-care healthcare workers’ adherence to recommended barrier precautions during the Toronto severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(11):1275–83.

Spranger CB, Villegas D, Kazda MJ, Harris AM, Mathew S, Migala W. Assessment of physician preparedness and response capacity to bioterrorism or other public health emergency events in a major metropolitan area. Disaster Manag Response. 2007;5(3):82–6.

Rebmann T, English JF, Carrico R. Disaster preparedness lessons learned and future directions for education: results from focus groups conducted at the 2006 APIC Conference. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(6):374–81.

Coombs GW, Van Gessel H, Pearson JC, Godsell MR, O’Brien FG, Christiansen KJ. Controlling a multicenter outbreak involving the New York/Japan methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(7):845–52.

Humphreys H. Control and prevention of healthcare-associated tuberculosis: the role of respiratory isolation and personal respiratory protection. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66(1):1–5.

Stone SP, Cooper BS, Kibbler CC, Cookson BD, Roberts JA, Medley GF, et al. The ORION statement: guidelines for transparent reporting of outbreak reports and intervention studies of nosocomial infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(4):282–8.

Gupta RK, Zhao H, Cooke M, Harling R, Regan M, Bailey L, et al. Public health responses to influenza in care homes: a questionnaire-based study of local Health Protection Units. J Public Health (Oxf). 2007;29(1):88–90.

Vinson E. Managing bioterrorism mass casualties in an emergency department: lessons learned from a rural community hospital disaster drill. Disaster Manag Response. 2007;5(1):18–21.

Santos SL, Helmer DA, Fotiades J, Copeland L, Simon JD. Developing a bioterrorism preparedness campaign for veterans: Using focus groups to inform materials development. Health Promot Pract. 2007;8(1):31–40.

Uscher-Pines L, Bookbinder SH, Miro S, Burke T. From bioterrorism exercise to real-life public health crisis: lessons for emergency hotline operations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(1):16–22.

Zerwekh T, McKnight J, Hupert N, Wattson D, Hendrickson L, Lane D. Mass medication modeling in response to public health emergencies: outcomes of a drive-thru exercise. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(1):7–15.

Murphy E, Black N, Lamping D, McKee C, Sanderson C. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development: a review. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(3):88.

Campbell SM, Cantrill JA. Consensus methods in prescribing research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(1):5–14.

Yeager VA, Menachemi N, McCormick LC, Ginter PM. The nature of the public health emergency preparedness literature 2000–2008: a quantitative analysis. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5):441–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all experts that participated in the consensus procedure for sharing their knowledge and practical experience on the subject. We thank the advisory group and consultative group for providing useful guidance for conducting the study, with special thanks to Prof. Koos van der Velden and Toos Waegemaekers. We thank Toos Waegemaekers and Sjaak de Gouw for chairing the consensus meetings. This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) who provided a research grant [grant number 204000003] to the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EB was the main study researcher. She corresponded with the experts, performed the literature search, extracted data from the selected literature, sent out the questionnaires, collected and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. JH co-designed the study and was responsible for the daily supervision of the study. She provided support for correspondence with the experts and advisory groups, data collection and analysis and reviewed all the manuscript drafts. MHi extracted data from the selected literature, attended the first consensus rounds for support and reviewed the final version of the manuscript. AT co-designed the study, made important contributions to the literature search and selection of studies. She attended the second consensus round for support and reviewed manuscripts drafts. MHu designed the study, provided methodological support for the study, and supervised the execution of the study design and methodology. She reviewed all the manuscript drafts. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Included grey literature.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Belfroid, E., LA Hautvast, J., Hilbink, M. et al. Selection of key recommendations for quality indicators describing good quality outbreak response. BMC Infect Dis 15, 166 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0896-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0896-x