Abstract

Background

Regular exercise is emphasized for the improvement of functional capacity and independence of older adults. This study aimed to compare the effects of a dual-task resistance exercise program and resistance exercise on cognition, mood, depression, physical function, and activities of daily living (ADL) in older adults with cognitive impairment.

Methods

A total of 44 older adults participated in the study. Participants were randomly allocated to an experimental group (n = 22) performing a dual-task resistance exercise program for cognitive function improvement and a control group (n = 22) performing a resistance exercise program. Both groups performed the exercise for 40 min per session, three times a week, for 6 weeks (18 sessions). Cognition, mood, depression, functional fitness, and ADL were quantified before and after the intervention using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), profile of mood states (POMS), geriatric depression scale (GDS), senior fitness test (SFT), and Korean version of ADL, respectively.

Results

There was a significant time and group interaction on the MMSE (p = 0.044). There were no significant time and group interactions in the POMS, GDS, SFT, or ADL. Cognitive function (p < 0.001), mood (p < 0.001), depression (p < 0.001), functional fitness (p < 0.001), and ADL (p < 0.001) significantly improved after dual-task resistance exercise, and cognitive function (p < 0.001), mood (p < 0.001), depression (p < 0.001), functional fitness (p < 0.001), and ADL (p < 0.001) significantly improved after resistance exercise.

Conclusions

Dual-task resistance exercise is more effective than resistance exercise in improving cognitive function in older adults with cognitive impairment. Both dual-task resistance exercise and resistance exercise improves mood, depression, functional fitness, and ADL after the intervention. We propose using dual-task resistance exercises for cognitive and physical health management in the older adults with cognitive impairment.

Trial registration

This study was registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) (Registration ID, KCT0005389; Registration date, 09/09/2020).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global aging phenomenon, an indispensable topic in modern society, has sharply increased interest in the lives of the older adult population. Therefore, unlike in ancient times when geriatric diseases were considered natural phenomena, maintaining and improving a healthy body has become a significant social concern [1]. According to a report released by the United Nations in 2020, the number of people aged 65 and over globally is estimated to be 728 million and is expected to reach 1.5 billion by 2050 [2]. In addition, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019) reported that 11.7% of adults over the age of 65 suffer from cognitive impairment [3]. Aging is associated with cognitive impairment and contributes to a decline in physical function [4, 5]. Decline in cognitive and physical function can reduce activities of daily life (ADL), leading to feelings of loneliness, alienation, and psychological atrophy, leading to an increase in depression in older adults [6,7,8]. Decreased physical functions may increase the risk and fear of falls, the incidence of geriatric diseases, and lead to a decrease in self-confidence in performing ADL [9, 10].

Physical exercise is considered an essential healthcare option for older people [11]. Regular exercise can have positive cognitive and physical effects, such as delaying aging-induced neurodegeneration and reducing the risk of falls and depression in older adults [12, 13]. Therefore, various studies are being conducted to improve older adults’ cognitive and physical functions. Resistance exercise is mainly used to prevent deterioration of physical functions due to aging [14]. Various literatures have also reported that resistance exercise helps to improve cognitive function by causing structural and functional changes in the brain [15,16,17,18].

Dual-task exercise program that combines cognitive training and physical activity programs for older adults with mild cognitive impairment has been reported [19]. Recent studies have also reported that dual-task training improved balance and gait function in patients with stroke [20] and spatio-temporal parameters of gait in older women with dementia [21]. A previous study has reported that exercises that include dual-task could be the key of therapeutic success to slow down the progression of dementia, but risk of falls during dual task performance compared to single task performance was presented in patients with dementia [22]. A recent systematic review suggested a further study on the capability of cognitive-motor dual-tasks related to falls in patients with stroke [23].

Recent research highlights the effectiveness of resistance exercise interventions in improving physical functionality, mood, and alleviating depression among older adults [14,15,16,17,18]. Additionally, previous studies have reported that exercises that applies dual tasks has demonstrated potential in enhancing cognitive capabilities [24,25,26,27,28]. Based on the findings of these previous studies, it is necessary to perform resistance exercise for the comprehensive management of cognition, emotion, depression, and physical health in older adults. Additionally, adopting a dual-task-based approach is crucial as it holds potential for enhancing cognitive function. The appropriate exercise program for managing older adults’ health is dual-task resistance exercise, which can deliver all the benefits of resistance exercise while additionally enhancing cognitive function.

Although there are various reports, controversy exists about dual-task interventions for the rehabilitation of patients with cognitive impairment and the efficacy of exercise programs to improve mood, depression, physical function, and ADL, along with improving cognitive function in older adults with cognitive impairment, is still insufficient. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis has reported positive effects of dual-task exercise on cognition and motor function in older adults with cognitive impairment, but several studies included in the systematic review compared experimental groups with control groups such as health education and placebo activities, not active comparators [29]. Studies in which the risk of selection bias existed were also included. Therefore, it is necessary to prepare evidence through methodologically appropriately designed studies to minimize bias.

This study aimed to examine the effects of an exercise program to improve cognition, mood, depression, physical function, and ADL in older adults with cognitive impairment. The experimental group performed a dual-task resistance exercise program aimed at improving cognitive function, and the control group performed a resistance exercise program. We hypothesized that dual-task resistance exercise would be more effective in improving cognition compared to resistance exercise. Additionally, we hypothesized that dual-task resistance exercise would have similar effects on mood, depression, physical function, and activities of daily living (ADL) as resistance exercise.

Methods

Design and ethic

This study was designed as a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. This study was approved by the CHA University Institutional Review Board on August 14, 2020 (No.1044308-202006-HR-019-02). This study was registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) on September 9, 2020 (study identifier, KCT0005389). Before participating in the study, participants were informed about the research procedure, and informed consent was obtained from all participants involved.

Participants

Among those wishing to participate, those who satisfied the following conditions were selected as participants [30, 31]; (1) those who were 65 years of age or older, (2) those with The Mini-Mental State Examination-Korean (MMSE-K) score of 23 or less, (3) those who could walk without a walking aid, and (4) those who could communicate in Korean and follow the instructions of the research team. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of stroke with movement impairment, (2) history of traumatic brain injury with a movement disorder, and (3) neurological or mental comorbidity other than cognitive impairment.

Sample size

To calculate the sample size, G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Universität Kiel, Kiel, Germany) was used, with an effect size of 0.25 (medium effect size) [32], ANOVA (repeated measures, within-between interaction), and two repeated measures. Thirty-four participants were required to achieve 80% power at an α level of 0.05. Based on these values, 43 participants were required, with a 20% dropout rate.

Intervention

Each group performed an exercise using a body spider (KOOPERA, Germany) for 40 min per session, three times a week, for 6 weeks (18 sessions) [33]. A body spider is an exercise device that uses the elasticity of a rubber rope, and both concentric and eccentric contractions are possible. It comprises a three-stage frame of the upper, middle, and lower parts; therefore, it is capable of whole-body exercise in various directions. Body spider was also used to confirm the effects of exercise in older adults [34]. The experimental group performed a dual-task resistance exercise program to improve cognitive function, and the control group performed a resistance exercise program for the same period using the same equipment (Table 1; Fig. 1). The individuals included in Fig. 1 are members of our research team, and we obtained written consent from them for publication.In both groups, warm-up exercise was performed for 10 min before main exercise and cool-down exercise was performed for 10 min after main exercise. The experimental group performed dual tasks such as writing names, drawing pictures, and subtracting numbers while performing the same resistance exercise applied to the control group. The control group performed resistance exercises for 20 min. At this time, the strength of the resistance exercise was measured at 1RM, and 3 sets were performed with approximately 10 reps per set, with a maximum of 12RM.

Outcome measures

Primary variable (cognitive function)

The MMSE-K was used to investigate changes in cognitive function. The MMSE-K consists of time orientation (five points), place orientation (five points), memory registration (three points), memory recall (three points), attention and calculation ability (five points), language function (seven points), and comprehension (two points). It consists of seven sub-items of judgment ability (two points), with a total score of 30 points. When the MMSE-K score exceeds 24, it is classified as definitively normal, and when it is under 24, it is judged that the cognitive function has deteriorated. This tool has excellent validity (0.93) [35].

Secondary variables (Mood state, Depression state, functional fitness, activities of daily living)

The Korean version of the Profile of Mood States (K-POMS) was used to assess participants’ mood states. The mood state profile has a total of 30 items and consists of six sub-domains: tension, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion. Responses were categorized using a 5-point Likert scale with 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 points for ‘not at all,’ ‘a little,’ ‘moderately,’ ‘quite a lot,’ and ‘extremely,’ respectively. The total mood disturbance is the sum of the scores of all five negative indicators (tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion) among the subcategories minus the positive indicator (vigor). A higher total score for mood state is interpreted as a lower mood state for the participant. The reliability coefficient is 0.93 [36].

The Korean geriatric depression scale (GDS-K) was used to assess older adults with the symptoms of depression. This measurement method is a nutrient scale in which the participant responds with yes/no, and 18 or more out of 30 items indicate depression. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the GDS-K is 0.90 [37].

Functional fitness was evaluated using the Senior Fitness Test (SFT) compiled by Rikli and Jones in 1999 [38]. Among the sub-items of the senior fitness test, a hand-held dynamometer instead of the 30-sec arm curl was used to evaluate upper extremity strength, a 30-sec chair stand to evaluate the remaining lower extremity strength, a 2-min step walk to evaluate endurance, 244 cm up and go to evaluate agility, back scratch to evaluate upper extremity flexibility, and chair sit and reach to evaluate lower extremity flexibility. Additionally, a one-leg standing test was used to evaluate static balance [39]. These assessments are also useful to investigate the risk of falls in older adults [40,41,42].

The Korean ADL (K-ADL) scale was used to quantify the participants’ ADL. The tool completed seven sub-items (dressing, washing face, bathing, eating, moving, using the toilet, and toileting) on a 3-point scale: (1) able to do alone without assistance, (2) need partial help, and (3) totally need help. It was structured to respond on a scale. The Cronbach’s alpha of the K-ADL was 0.93 [43].

Procedure

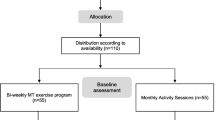

In this study, A recruitment notice was posted at a senior day care center located in Goyang, South Korea. Participants who agreed to participate and met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups using permuted block randomization (block size 4). Allocation concealment was performed by placing sequentially numbered, opaque, and sealed envelopes. Participants were randomly allocated to an experimental group that performed a dual-task resistance exercise program for cognitive function improvement and a control group that performed a resistance exercise program. All assessments and interventions were conducted in the senior day care center.

Interventions were conducted for 40 min per session, three times a week, 18 times for 6 weeks, from October 13 to November 21, 2020 (18 sessions). All interventions were performed under the supervision of two physical therapists with 3 or more years of clinical experience. Five (or four) older adults and one physical therapist were a team. Both the experimental group and the control group were composed of 5 teams. Participants performed exercises using body spiders following the instructions of the physical therapist. Except for the chair stand up of the warm-up exercise, all exercises were performed in a sitting position. A physical therapist in each group instructed each group’s exercise until all interventions were completed.

The exercise program conducted in this study was directly supervised by a physical therapist, with the duration set at a level that ensured participants with cognitive impairment did not experience undue discomfort or burden. During all interventions and assessments, researchers and safety personnel stood right next to the participants in case anything went wrong with them. Participants were informed that they were free to withdraw from the program if they felt burdened during the study period.

When assessing cognitive function, mood state, depressive state, functional fitness, and activities of daily living, group information was not provided to the assessor. Before the intervention, the participants were asked to complete the questionnaire, and participants who had difficulty reading texts were allowed to complete the questionnaire as the researcher read it. After 18 interventions, the same variables were assessed in the same way.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For comparison between groups on the general characteristics of participants, the chi-square test was used for categorical variables, and the independent t-test was used for continuous variables. A mixed analysis of variance was performed to analyze the time and group interaction for each dependent variable. A paired t-test was performed for the average difference between two time points in each group, and the significance level was corrected using Bonferroni correction. The statistical significance level was set at α = 0.05.

Results

General characteristics of participants

Of the 54 recruits, three declined to participate and seven met the exclusion criteria. A total of 44 people participated in the experiment, and the experiment was conducted by randomly dividing the participants into 2 groups. No person was excluded from the assessment or analysis (Fig. 2).

The general characteristics of the participants are presented (Table 2). Among the 44 participants, 15 (34.1%) males and 29 (65.9%) females were divided into 22 in the experimental group and 22 in the control group. Regarding sex, 7 males and 15 females were in the exercise group, and 8 males and 14 females were in the control group. There was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in sex ratio, mean age, height, weight, and body mass index. Cognitive function, mood state, depression state, functional fitness, activities of daily living showed no significant differences of pre-values between two groups.

Cognitive function

Table 3 shows the changes in cognitive function over time between the experimental and control groups (Table 3) (Fig. 3). There was significant time and group interaction for cognitive function (F = 4.333, df = 1, p = 0.044). The cognitive scores of the experimental group significantly increased after the intervention (p < 0.001). The control group also showed a significant increase in cognitive function post-intervention (p < 0.001).

Comparisons of changes for each variable. Observed changes in each variable from pre- to post-intervention. A MMSE-K, B K-POMS, C K-GDS, D Back scratch, E Chair sit and reach, F 244 cm up and go, G 2-min step walk, H 30-sec chair stand, I Grip strength – Lt., J Grip strength – Rt., K One leg standing, L K-ADL. Orange-colored bars represent pre-intervention, while Blue-colored bars represent post-intervention. Bar length and error bar expressed mean and standard deviation, respectively. *Significant difference in within-group; †Significant time and group interaction. MMSE-K, mini-mental state examination-KOREA; K-POMS, Korean-profile of mood states; K-GDS, Korean-geriatric depression scale, Lt., Light; Rt., Right; K-ADL, Activities daily of living

Mood state

Table 3 shows the mood states according to time between the experimental and control groups (Table 3) (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to time (F = 3.781, df = 1, p = 0.059). The mood state scores of the experimental and control groups significantly decreased after the intervention (p < 0.001 for both).

Depression state

Table 3 shows the depression states of the experimental and control groups (Table 3) (Fig. 3). There was no significant interaction between time and group on the GDS (F = 2.751, df = 1, p = 0.105). The depression score of the experimental group significantly decreased after the intervention (p < 0.001), and the degree of depression in the control group showed a significant change after the intervention (p < 0.001).

Functional fitness

Table 4 shows the results of significant changes in body function over time between the experimental and control groups to which the single task program was applied (Table 4) (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference between time and group in terms of physical function (back scratch, F < 0.001, df = 1, p = 0.986; chair sit and reach, F = 0.001, df = 1, p = 0.977; 244 cm up and go, F = 1.297, df = 1, p = 0.261; 2-min step walk, F = 0.170, df = 1, p = 0.682; 30-sec chair stand, F = 2.528, df = 1, p = 0.119; left grip strength, F = 0.128, df = 1, p = 0.722; right grip strength, F = 1.408, df = 1, p = 0.242; one-leg standing test F = 0.217, df = 1, p = 0.644). In both groups, significant differences were observed before and after the intervention in all sub-variables assessed by the senior fitness test (p < 0.001).

Activities of daily living

Table 4 shows the changes in ADL over time between the experimental group to which the cognitive management exercise program was applied and the control group to which the single-task exercise program was applied (Table 4) (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference between the groups with respect to time spent in ADL (F = 0.052, df = 1, p = 0.820). The ADL score of the experimental group significantly improved after the intervention (p < 0.001), and the ADL score of the control group significantly changed after the intervention (p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of dual-task resistance exercise on cognitive function, mood state, depressive state, functional fitness, and ADL in older adults with cognitive impairment. Compared to the resistance exercise group, there was a significant improvement in cognition in the dual-task resistance exercise group. Both dual-task and resistance exercises significantly improved mood, depression, functional fitness, and ADL.

The importance of physical activity is gradually gaining attention, as previous studies have shown that an increase in physical activity improves cognitive function in older adults [44]. However, the debate continues how much more cognitive improvement benefits dual-task exercises have compared to single-task exercises [45]. The results of this study showed that performing cognitive tasks had a significant advantage in improving cognitive function when the same amount of exercise was performed. This can be interpreted in the same context as recently published studies. In various participants, dual-tasks have been found to have advantages in cognitive function compared with single tasks [45,46,47,48,49]. These results suggest that secondary components, such as inhibition, planning, and execution of motor response, which activate executive functions required to respond to external stimuli, can provide better cognitive benefits when they work together with exercise [50].

Even in the active control group that performed a resistance exercise, cognitive function showed improvement compared to that before the intervention. A previous study have also confirmed Improvements in cognition when resistance exercise was performed in older adults with reduced physical activity [51]. Improvements in cognitive function were confirmed in both groups; however, there was a significant difference in the time-group interaction between the experimental and control groups, indicating that the health benefits of the dual-task were more effective when the intervention was performed for the same period. The human body routinely performs multiple tasks simultaneously, a concept known as dual-tasking, which is crucial for daily functioning. Older adults, especially those experiencing declines in cognitive and physical capabilities, often struggle with these simultaneous demands. Decreased cognitive and physical activity can lead to further declines in overall function [52, 53]. The results of this study showed that managing cognitive and physical functions in older adults through exercise is feasible.

Resistance exercise not only has a positive effect on cognitive function [51], reduces depression and anxiety [54, 55], and increases self-esteem and psychological well-being [56, 57]. Similar to these previous studies, both the dual-task and resistance exercise groups showed improvements in mood and depression before and after the intervention. This is not different from the results that the intensification of depression was highly correlated with cognitive functions, such as impairment of executive function and processing speed [58], and that an increase in physical activity had a positive effect on improving mood and depression in older adults [59, 60]. According to a report by Blumenthal et al., when older adults with depression were asked to exercise regularly, the depression and recurrence rates were lower in the exercise group than in the group taking antidepressant drugs for the same period [61]. Combining this with the results of this study, it is suggested that regular exercise can be as effective as drug treatment in improving depression in older adults. Additionally, physical activity, as facilitated through group exercise, such as the intervention used in this study, appears to have strengthened social networks and provided psychological stability [62,63,64].

Older adults who engage in regular physical activity are less likely to experience reduced mobility, perform better in ADLs and have higher levels of functional fitness [65]. Furthermore, compared to the elderly population with no physical activity at all, those engaging in physical activity have a lower risk of developing functional limitations, can maintain independence, improves quality of life, and significantly reduce the risk of death [66]. For older individuals with cognitive impairment, engaging in appropriate physical activity becomes challenging, which can make cognitive impairment more severe [67, 68]. In our study, functional fitness and ADL in both groups significantly improved after the intervention. It is presumed that participants who had low physical activity at a nursing institution experienced increased physical strength and improved efficiency in ADL by continuously practicing regular physical activity [69]. This means that social medical expenses can be reduced by preventing the aggravation of disabilities and diseases experienced in daily life through exercise [70].

Although the importance of physical functioning is greatly emphasized across all age groups, maintaining and improving cognitive function tends to be seen as a limited social problem in some populations [71]. However, as mentioned earlier, cognitive function is closely related to depression and has a social advantage in that it increases the quality of life of older adults by inducing the resolution of negative emotions through the improvement of cognitive function. Therefore, the maintenance and improvement of cognitive function in human health promotion is an issue that should be considered along with physical function [72].

This study presents a specific approach to exercise interventions for older adults with cognitive impairment by comparing the effects of dual-task resistance exercise against resistance training. Dual-task resistance exercise demonstrated greater effectiveness in improving cognition while producing equivalent results to resistance exercise applied at the same frequency and duration. This study contributes to the understanding of exercise science by providing a comprehensive assessment of how such interventions impact cognition, mood, depression, physical function, and activities of daily living. The findings suggest dual-task resistance exercises may serve as a more effective method for improving cognitive and physical health in aging populations. Additionally, it contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting dual-task exercise programs as essential tools in managing cognitive health. Lastly, the study lays a foundation for future research, encouraging further exploration into optimizing exercise interventions for cognitive improvement among older adults.

This study has some limitations. First, because the participants knew the group to which they belonged, the possibility of the risk of performance bias cannot be excluded. Second, by comparing only before and after the intervention, it was not possible to determine the most appropriate intervention dose. Third, since follow-up assessments were not performed, the persistence of the intervention effect cannot be determined. Lastly, MMSE used in cognitive assessment is a tool with high reliability and validity, but individual characteristics such as education level or social background may influence the results, and that it may have limitations in detecting cognitive impairment at an early stage or certain types of cognitive impairment [73].

Conclusion

The 6-week dual-task resistance exercise program was more effective than the resistant exercise program in improving cognitive function in older adults with cognitive impairment. Both dual-task resistance exercise and resistance exercise groups significantly improved mood, depression, functional fitness, and ADL after the intervention. For mood, depression, functional fitness, and ADL, equivalent effects were confirmed between dual-task resistance exercise and resistance exercise groups. Based on this study’s results, we propose using dual-task resistance exercises for cognitive and physical health management in the older adult population.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- GDS:

-

Geriatric Depression Scale

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- POMS:

-

Profile Of Mood States

- SFT:

-

Senior Fitness Test

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in aging–United States and worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:101–6.

United Nations. Government policies to address population ageing. 2020. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2020_pf_government_policies_population_ageing.pdf . Accessed 20 Sept 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Subjective Cognitive Decline — A Public Health Issue. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/data/subjective-cognitive-decline-brief.html . Accessed 20 Sept 2022.

Deary IJ, Corley J, Gow AJ, Harris SE, Houlihan LM, Marioni RE, et al. Age-associated cognitive decline. Br Med Bull. 2009;92:135–52.

Vaillant GE, Mukamal K. Successful aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:839–47.

Krause-Parello CA, Gulick EE, Basin B. Loneliness, Depression, and physical activity in older adults: the therapeutic role of human–animal interactions. Anthrozoos. 2019;32:239–54.

Cordes T, Bischoff LL, Schoene D, Schott N, Voelcker-Rehage C, Meixner C, et al. A multicomponent exercise intervention to improve physical functioning, cognition and psychosocial well-being in elderly nursing home residents: a study protocol of a randomized controlled trial in the PROCARE (prevention and occupational health in long-term care) project. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:369.

Wang R, Zhang D, Wang S, Zhao T, Zang Y, Su Y. Limitation on activities of daily living, depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among nursing home residents: the moderating role of resilience. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap). 2020;41:622–8.

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:M255-263.

Buckinx F, Rolland Y, Reginster J-Y, Ricour C, Petermans J, Bruyère O. Burden of frailty in the elderly population: perspectives for a public health challenge. Archives Public Health. 2015;73:19.

Paterson DH, Jones GR, Rice CL. Ageing and physical activity: evidence to develop exercise recommendations for older adults. Can J Public Health. 2007;98(Suppl 2):S69-108.

Rodziewicz-Flis EA, Kawa M, Skrobot WR, Flis DJ, Wilczyńska D, Szaro-Truchan M, et al. The positive impact of 12 weeks of dance and balance training on the circulating amyloid precursor protein and serotonin concentration as well as physical and cognitive abilities in elderly women. Exp Gerontol. 2022;162:111746.

Mora JC, Valencia WM. Exercise and older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34:145–62.

Herold F, Törpel A, Schega L, Müller NG. Functional and/or structural brain changes in response to resistance exercises and resistance training lead to cognitive improvements – a systematic review. Eur Rev Aging Phys Activity. 2019;16:10.

Chang H, Kim K, Jung Y-J, Kato M. Effects of acute high-intensity resistance exercise on cognitive function and oxygenation in prefrontal cortex. J Exerc Nutr Biochem. 2017;21:1–8.

Coetsee C, Terblanche E. Cerebral oxygenation during cortical activation: the differential influence of three exercise training modalities. A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017;117:1617–27.

Hong S-G, Kim J-H, Jun T-W. Effects of 12-week resistance exercise on electroencephalogram patterns and cognitive function in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;28:500–8.

Tsai C-L, Wang C-H, Pan C-Y, Chen F-C, Huang T-H, Chou F-Y. Executive function and endocrinological responses to acute resistance exercise. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8.

Ali N, Tian H, Thabane L, Ma J, Wu H, Zhong Q, et al. The effects of dual-task training on cognitive and physical functions in older adults with cognitive impairment; a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2022.16.

Chiaramonte R, Bonfiglio M, Leonforte P, Coltraro GL, Guerrera CS, Vecchio M. Proprioceptive and dual-task training: the key of stroke rehabilitation, a systematic review. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2022;7:53.

Ghadiri F, Bahmani M, Paulson S, Sadeghi H. Effects of fundamental movement skills based dual-task and dance training on single- and dual-task walking performance in older women with dementia. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap). 2022;45:85–92.

Chiaramonte R, Cioni M. Critical spatiotemporal gait parameters for individuals with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hong Kong Physiotherapy J. 2021;41:1–14.

Abdollahi M, Whitton N, Zand R, Dombovy M, Parnianpour M, Khalaf K, et al. A systematic review of fall risk factors in stroke survivors: towards Improved Assessment platforms and protocols. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:910698.

Jhaveri S, Romanyk M, Glatt R, Satchidanand N. SMARTfit Dual-Task Exercise improves cognition and physical function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: results of a community-based pilot study. J Aging Phys Act. 2023;31:621–32.

Jardim NYV, Bento-Torres NVO, Costa VO, Carvalho JPR, Pontes HTS, Tomás AM, et al. Dual-task exercise to improve cognition and functional capacity of healthy older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:13.

Raichlen DA, Bharadwaj PK, Nguyen LA, Franchetti MK, Zigman EK, Solorio AR, et al. Effects of simultaneous cognitive and aerobic exercise training on dual-task walking performance in healthy older adults: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:83.

Pothier K, Gagnon C, Fraser SA, Lussier M, Desjardins-Crépeau L, Berryman N, et al. A comparison of the impact of physical exercise, cognitive training and combined intervention on spontaneous walking speed in older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30:921–5.

Bherer L, Gagnon C, Langeard A, Lussier M, Desjardins-Crépeau L, Berryman N, et al. Synergistic effects of cognitive training and physical exercise on dual-task performance in older adults. J Gerontol Ser B. 2021;76:1533–41.

Uysal İ, Başar S, Aysel S, Kalafat D, Büyüksünnetçi AÖ. Aerobic exercise and dual-task training combination is the best combination for improving cognitive status, mobility and physical performance in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;35:271–81.

Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:922–35.

Montero-Odasso M, Casas A, Hansen KT, Bilski P, Gutmanis I, Wells JL, et al. Quantitative gait analysis under dual-task in older people with mild cognitive impairment: a reliability study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2009;6: 35.

Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge; 2013.

Boripuntakul S, Kothan S, Methapatara P, Munkhetvit P, Sungkarat S. Short-term effects of cognitive training program for individuals with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2012;30:138–49.

Prinz A, Langhans C, Rehfeld K, Partie M, Hökelmann A, Witte K. Effects of Music-based physical training on selected motor and cognitive abilities in seniors with dementia-results of an intervention pilot study. J Geriatr Med Gerontol. 2021;7:7.

Kim JM, Shin IS, Yoon JS, Lee HY. Comparison of Diagnostic validities between MMSE-K and K-MMSE for Screening of Dementia. J Korean Neuropsychiatric Association. 2003;42:124–30.

Kim EJ, Lee SI, Jeong DU, Shin MS, Yoon IY. Standardization and reliability and validity of the Korean Edition of Profile of Mood States (K-POMS). Sleep Med Psychophysiol. 2003;10:39–51.

Bae JN, Cho MJ. Development of the Korean version of the geriatric depression scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:297–305.

Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Development and validation of a functional fitness test for community-residing older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7:129–61.

Lohne-Seiler H, Kolle E, Anderssen SA, Hansen BH. Musculoskeletal fitness and balance in older individuals (65–85 years) and its association with steps per day: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:6.

Rose DJ, Jones CJ, Lucchese N. Predicting the probability of falls in community-residing older adults using the 8-foot up-and-go: a new measure of functional mobility. J Aging Phys Act. 2002;10:466–75.

Zhao Y, Chung P-K. Differences in functional fitness among older adults with and without risk of falling. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2016;10:51–5.

Peng H-T, Tien C-W, Lin P-S, Peng H-Y, Song C-Y. Novel mat exergaming to improve the physical performance, cognitive function, and dual-task walking and decrease the fall risk of community-dwelling older adults. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1620.

Won CW, Rho YG, Kim SY, Cho BR, Lee YS. The validity and reliability of Korean activities of Daily Living(K-ADL) Scale. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2002;6:98–106.

Dik MG, Deeg DJH, Visser M, Jonker C. Early Life Physical Activity and Cognition at Old Age. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25:643–53.

Fritz NE, Cheek FM, Nichols-Larsen DS. Motor-cognitive dual-task training in persons with neurologic disorders. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2015;39:142–53.

Choi JH, Kim BR, Han EY, Kim SM. The effect of dual-task training on balance and cognition in patients with subacute post-stroke. Ann Rehabil Med. 2015;39:81.

Pereira Oliva HN, Mansur Machado FS, Rodrigues VD, Leão LL, Monteiro-Júnior RS. The effect of dual-task training on cognition of people with different clinical conditions: an overview of systematic reviews. IBRO Rep. 2020;9:24–31.

Maclean LM, Brown LJE, Khadra H, Astell AJ. Observing prioritization effects on cognition and gait: the effect of increased cognitive load on cognitively healthy older adults’ dual-task performance. Gait Posture. 2017;53:139–44.

Elkana O, Louzia-Timen R, Kodesh E, Levy S, Netz Y. The effect of a single training session on cognition and mood in young adults – is there added value of a dual-task over a single-task paradigm? Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2022;20:36–56.

Tait JL, Duckham RL, Milte CM, Main LC, Daly RM. Influence of sequential vs. simultaneous dual-task exercise training on cognitive function in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:368.

Landrigan J-F, Bell T, Crowe M, Clay OJ, Mirman D. Lifting cognition: a meta-analysis of effects of resistance exercise on cognition. Psychol Res. 2020;84:1167–83.

Montero-Odasso M, Verghese J, Beauchet O, Hausdorff JM. Gait and cognition: a complementary approach to understanding brain function and the risk of falling. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2127–36.

Beurskens R, Bock O. Age-related deficits of dual-task walking: a review. Neural Plast. 2012;2012:1–9.

Gordon BR, McDowell CP, Hallgren M, Meyer JD, Lyons M, Herring MP. Association of efficacy of resistance exercise training with depressive symptoms. JAMA Psychiat. 2018;75:566.

Gordon BR, McDowell CP, Lyons M, Herring MP. The effects of resistance exercise training on anxiety: a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 2017;47:2521–32.

Tsutsumi T, Don BM, Zaichkowsky LD, Delizonna LL. Physical fitness and psychological benefits of strength training in community dwelling older adults. Appl Hum Sci. 1997;16:257–66.

Dionigi R. Resistance training and older adults’ beliefs about psychological benefits: the importance of self-efficacy and social interaction. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29:723–46.

McDermott LM, Ebmeier KP. A meta-analysis of depression severity and cognitive function. J Affect Disord. 2009;119:1–8.

Matsouka O, Kabitsis C, Harahousou Y, Trigonis I. Mood alterations following an indoor and outdoor exercise program in healthy elderly women. Percept Mot Skills. 2005;100:707–15.

Yoshiuchi K, Nakahara R, Kumano H, Kuboki T, Togo F, Watanabe E, et al. Yearlong physical activity and depressive symptoms in older Japanese adults: cross-sectional data from the Nakanojo Study. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:621–4.

Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, Craighead WE, Herman S, Khatri P, et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2349–56.

Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Saito Y, Oguma Y. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:190.

Zimmer C, McDonough MH, Hewson J, Toohey A, Din C, Crocker PRE, et al. Experiences with social participation in group physical activity programs for older adults. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2021;43:335–44.

Sebastião E, Mirda D. Group-based physical activity as a means to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33:2003–6.

Paterson DH, Warburton DE. Physical activity and functional limitations in older adults: a systematic review related to Canada’s Physical Activity guidelines. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2010;7:38.

Fukushima N, Kikuchi H, Sato H, Sasai H, Kiyohara K, Sawada SS, et al. Dose-response relationship of physical activity with all-cause mortality among older adults: an Umbrella Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2023.09.028 .

Schlosser Covell GE, Hoffman-Snyder CR, Wellik KE, Woodruff BK, Geda YE, Caselli RJ, et al. Physical activity level and future risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Neurologist. 2015;19:89–91.

Liu X, Jiang Y, Peng W, Wang M, Chen X, Li M. Association between physical activity and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults: Depression as a mediator. Front Aging Neurosci., Galán-Mercant A, Carnero EA, Fernandes B et al. Functional Capacity and Levels of Physical Activity in Aging: A 3-Year Follow-up. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;4:964886.

Tomás MT, Galán-Mercant A, Carnero EA, Fernandes B. Functional capacity and levels of physical activity in aging: a 3-Year follow-up. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;4:244.

Tak E, Kuiper R, Chorus A, Hopman-Rock M. Prevention of onset and progression of basic ADL disability by physical activity in community dwelling older adults: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:329–38.

Joosten H, van Eersel MEA, Gansevoort RT, Bilo HJG, Slaets JPJ, Izaks GJ. Cardiovascular Risk Profile and cognitive function in young, middle-aged, and elderly subjects. Stroke. 2013;44:1543–9.

Ko H, Jung S. Association of Social Frailty with Physical Health, cognitive function, Psychological Health, and life satisfaction in Community-Dwelling Older koreans. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18: 818.

Matthews F, Marioni R, Brayne C. Examining the influence of gender, education, social class and birth cohort on MMSE tracking over time: a population-based prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12: 45.

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation to the participants of this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A2A03042018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JEB contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, project administration, and writing of the original draft. SJH contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, and writing of the original draft. MK contributed to the resources, investigation, and funding acquisition. HWC contributed to the methodology, investigation, resources, supervision, and writing of the manuscript (review/editing). SCH contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, supervision, and writing of the manuscript (review/editing). All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the CHA University Institutional Review Board (No.1044308-202006-HR-019-02). This study was registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) (Registration ID, KCT0005389; Registration date, 09/09/2020). Before participating in the study, participants were informed about the research procedure, and informed consent was obtained from all participants involved.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication has been obtained from the participants in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Baek, JE., Hyeon, SJ., Kim, M. et al. Effects of dual-task resistance exercise on cognition, mood, depression, functional fitness, and activities of daily living in older adults with cognitive impairment: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 24, 369 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04942-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04942-1