Abstract

Background

As a common psychological problem among older adults, fear of falling was found to have a wide range prevalence in different studies. However, the global prevalence of it was unknown and a lack of the large sample confirmed its risk factors.

Objectives

To report the global prevalence of fear of falling and to explore its risk factors among older adults for further developing precise interventions to systematically manage FOF.

Design

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted by PRISMA guidelines.

Methods

Searches were conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library and the manual search in August 20, 2022, updated to September 2, 2023. Observational studies published in English were included and two researchers independently screened and extracted the data. Fixed or random effects mode was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of and risk factors for fear of falling. Heterogeneity resources were analyzed by subgroup and sensitivity analysis. Publication bias was assessed through funnel plots, Egger’s test and Begg’s test.

Results

A total of the 153 studies with 200,033 participants from 38 countries worldwide were identified. The global prevalence of fear of falling was 49.60%, ranging from 6.96–90.34%. Subgroup analysis found the estimates pooled prevalence of it was higher in developing countries (53.40%) than in developed countries (46.7%), and higher in patients (52.20%) than in community residents (48.40%). In addition, twenty-eight risk factors were found a significant associations with fear of falling, mainly including demographic characteristics, physical function, chronic diseases and mental problems.

Conclusion

The global prevalence of FOF was high, especially in developing countries and in patients. Demographic characteristics, Physical function, chronic diseases and mental problems were a significant association with FOF. Policy-makers, health care providers and government officials should comprehensively evaluate these risk factors and formulate precise intervention measures to reduce FOF.

Trial registration

The study was registered in the International Database of Prospectively Registered Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42022358031.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Falls have emerged as a major health issues, and health care is paying increasing attention to them as the primary cause of illness and early mortality among older adults. At least one in three older adults experience a fall each year, and fear of falling (FOF) causes more falls [1]. Negative fall-related consequences, such as fear of falling, increase the likelihood of disability and declining quality of life in relation to health [2]. FOF has been defined as the low perceived self-efficacy at avoiding falls in daily activities [3]. FOF is prevalent in older adults and may lead to several negative health outcomes such as changing gait [4], restricting daily activities [5], developing depression [5], increasing the risk of falls [6], and negatively impacting quality of life [2]. Earlier studies revealed that the 8-year mortality rate was nearly 14% greater among older adults with FOF than among those without FOF, and 16% greater among older adults with limited activities than among those without restricted activities [7]. In particular, avoiding certain situations can lead to fear of falling, which exacerbates poor physical health, balance concerns, and social isolation [8].

Fear of falling is common among older adults regardless of they have a history of falls. A study showed that the prevalence of FOF ranged from 3 to 85% among community-dwelling older adults with a history of falls [9]. However, different individuals and those from other nations reported the prevalence of FOF in different ways. FOF also occurs frequently among hospitalized patients [10, 11], especially among those who have undergone total knee arthroplasty [12], who have a hip fracture [13], and who have diabetic neuropathy [14]. Similarly, more than 50% of people with Parkinson’s disease had high levels of FOF, while close to 30% had moderate levels [15]. Previous studies demonstrated that there was significant variation in the incidence of FOF among older adults living in communities of different nationalities., ranging from 9.26% to 83.33% in the USA [16, 17], from 22.31% to 86.46% in Japan [18, 19], from 38.84% to 96.70% in Korea [20, 21], from 37.03% to 51.38% in Spain [22, 23], and from 44.56% to 86.71% in Turkey [24, 25]. At present, various tools are available to assess FOF, including the single question “Are you afraid of falling?”, the Falls Efficacy Scale (FES), the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I), the Short Falls Efficacy Scale International (SFES-I), the Modified fall efficacy scale(MFES) and the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale (ABC). Moreover, earlier studies showed that similar results were obtained utilizing a single-question tool and various structured questionnaire instruments [26].

Age, female sex, balance, living alone, chronic illnesses, and psychiatric issues were all risk factors for FOF. People with neurological disease and a history of falls in the previous 6 months were more than twice as likely to have FOF, while those with depression were more than six times more likely to have FOF [27]. Compared with nonfrail older adults, those with a frail physical condition and lack of daily activity had a greater than three times greater risk of experiencing FOF, and both female sex and depression found to be independent predictors of FOF [28]. A systematic review revealed that FOF in stroke patients was closely correlated with female sex, impaired balance ability, decreased mobility, a history of falls and walking aids, and decreased weight, which may present more challenges for impaired balance ability and excessive safety awareness of life circumstances and daily activities, increasing the risk of FOF and leading to the development of psychological stress [29]. Evidence has shown that gait variability, such as slowing gait speed, shorter strides, and widening strides, is similarly associated with FOF; however there are no conclusive findings from brain imaging to date [4]. Cognitive impairment, which was confirmed to be a predictor of having a significant effect on a high level of FOF, could increase the risk of accepting high FOF by three times in the older adults with low and moderate levels of social support caused by limited social activity, lack of family support and an aging-unfriendly environment [30]. Additionally, chemotherapy might make cancer patients more feeble and reduce their postural and limb stability because taxanes and platinum drugs harm muscle and peripheral nerve tissue, which reduces the efficacy of falls [31].

In conclusion, FOF is complicated by people’s physical, psychological, and social support systems, and its occurrence varies widely among studies involving different subjects, tools, and nations. Notably, the global prevalence of FOF is currently unknown. Therefore, this study includes a systematic review and meta-analysis to address the limitations of previous studies by estimating the global prevalence of FOF among older adults and fully exploring its risk factors for further developing precise interventions to systematically manage FOF.

Methods

Design

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines and was registered in the International Database of Prospectively Registered Systematic Reviews (ROSPERO: CRD42022358031).

Search methods

A systematic search of the literature was performed in PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library from the inception of the database until August 20, 2022, and updated to September 2, 2023. The search strategies were developed using a combination of MeSH terms and free words with Boolean operators. The details were as follows: (“Aged”[Mesh] OR “older” OR “older adult” OR “older” OR “elderly” OR “the aged”) AND (“fear of falling”) AND (“influence factors” OR “risk factors”) (see PubMed search strategies in Supplementary Material 1) and manually searched methods were used to check potential studies.

Inclusion and/or exclusion criteria

After removing duplicate studies, two reviewers independently reviewed studies based on the title and abstract and subsequently screened the literature based on full-text via the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows: 1) participants were at least 60 years old; 2) the prevalence or risk factors for FOF were reported; 3) the study design was observational study, including cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies; and 4) the study was published in the English language. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) full-text could not be obtained, or 2)incomplete or erroneous data.

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two researchers with the following variables: first author name, publication year, country, type of study instrument, subject, age, female ratio, sample size, prevalence of FOF, quality of studies and risk factors for FOF. If FOF was assessed using kinds of different instruments, the prevalence of FOF was extracted according to the results of the eligible studies. All disagreements were resolved by discussion between two researchers, and a third researcher was consulted if needed.

Quality assessment

Two researchers independently assessed the possibility of bias, and disagreements were settled by discussion or consultation with a third researcher. The quality of the case-control and cohort studies was assessed by using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [32], which has 8 items and a total score ranging from 0 to 9, and scores ranging from 0 to 3, 4 to 6 and 7 to 9 indicated low, medium and high quality, respectively. The quality of cross-sectional studies was assessed by using the instrument Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [33] with a total scores ranging from 0 to 11, and scores ranging from 0 to 3, 4 to 7 and 8 to 11 indicating low, medium, and high quality, respectively. The detailed items of the AHRQ and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale are shown in Supplementary Material 2.

Data analysis

Stata 12.0 software was used to analyze all the data, and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated as the effect size meanwhile 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were provided. Heterogeneity was tested by I2, and I2 > 50% indicated high heterogeneity while I2 < 50% indicated low heterogeneity [34]. Pooled effect size was analyzed using a fixed-effects model if I2 < 50%. Subgroup and sensitivity analysis were used to analyze the sources of heterogeneity if I2 > 50%, and subsequently, a random effects model was used. To assess risk factors for FOF, the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs, which reported the association between risk factors and FOF in eligible studies, were extracted to estimate the pooled effect size in meta-analyses using a fixed-effects model if I2 < 50%, or a random effects model if I2 > 50%. Publication bias was assessed through funnel plots, Egger’s test and Begg’s test [35].

Results

Study process

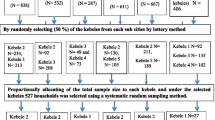

A total of 3452 studies were retrieved from databases and manual searches, and 1491 duplicate studies were eliminated. A total of 277 studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected after screening titles and abstracts, 124 of which were excluded after screening the full text: 16 did not publish in English, 67 did not report the prevalence of FOF, and 41 did not provide the full text. Finally, 153 studies with 200,033 participants from 38 countries were included and analyzed (shown in Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the 153 studies, 64(41.83%) of which were of medium quality and 89(58.17%) of which were of high quality, are summarized in Table 1. The publication years of all studies ranged from 1994 to 2023, and there were 200,033, with 112,697(56.34%)female. The details of the 153 studies are shown in Supplementary Material 3.

Global prevalence of FOF

The global prevalence of FOF among older adults widely ranged from 6.96% to 90.34% in the 153 studies. The overall prevalence of FOF was 47.80% [95% CI: 47.7%–48.0%], with high heterogeneity (χ2 = 50,648.15, I2 = 99.7%, p < 0.001). A random effects model was then constructed, and the results showed that the overall prevalence of FOF was 49.60% [95% CI:45.9%–53.2%, I2 = 99.7%, p < 0.001] (as shown in Supplementary Material 3).

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis by region, country, subject and instrument used is shown in Table 2. The estimates of the pooled prevalence of FOF were higher in Africa and Asia than in other regions, at 56.80% and 52.90%, respectively; were higher in developing countries (53.40%) than in developed countries (46.7%); and were higher in patients (52.20%) than in community residents (48.40%). Moreover, there is a difference in the prevalence of FOF among different instruments.

Risk factors for FOF

A total of thirty-eight risk factors for FOF were analyzed, and twenty-eight of them were significant significantly associated FOF (p < 0.05), including demographic characteristics (e.g., female sex, age (70–84 years), low education level, living alone, high BMI, etc.), physical function(e.g., using walking aid, frailty status, poor perceived health, Timed Up and Go test results (abnormal), balance problems), chronic diseases(e.g., diabetes, hearing impairment, visual impairment, body pain, dizziness, number of chronic diseases, etc.) and mental problems (e.g., anxiety and depression), while ten of them were not (p > 0.05), as shown in Table 3.

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Begg’s test (z = 1, p = 0.320) and Egger’s test (t = 15.34, p < 0.001) revealed the potential publication bias of the included literature, and the funnel plot showed a asymmetry (shown in Fig. 2). However, the sensitivity analysis of this finding was robust (shown in Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study was the first systematic review and meta-analysis to analyze the global prevalence of FOF among older adults, and to fully explore its potential risk factors. A total of 153 studies involving 200,033 participants from 38 countries revealed that the prevalence of FOF ranged widely from 6.96% to 90.34%, which was lower than that reported (ranging from 22.5% to 100%) among hip fracture patients [168], and the pooled global prevalence of FOF was high at 49.60%, which was similar to the results (44.6%) of previous research [25]. Subgroup analysis revealed that the pooled prevalence of FOF was higher in Africa and Asia than in other regions, higher in developing countries than in developed countries, and higher in patients than in community residents. In addition, twenty-eight potential risk factors were found to be significantly associated with FOF, mainly including demographic characteristics, physical function, chronic diseases and mental problems, which was the same as that reported in earlier studies [29, 169].

Overall, this study revealed that the global prevalence of FOF among older adults was high. One important reason was the increasing aging of the global population, which increased the prevalence of FOF among older adults. The WHO’s Aging and Health Report showed that in older adults, falls, as one of the common health conditions associated with aging, could lead to major public health problems and socioeconomic burdens [170], and FOF, as a fall-related mental problem, could increase older adults’ risk of falls, and these two factors could form a vicious cycle. Unlike in general older adults, the prevalence of FOF among patients after hip fracture tended to decrease within 4 weeks, approximately 12 weeks and over 12 weeks, at 50% to 100%, 47% to 59%, and 23% to 50%, respectively [168]. Moreover, the findings of this study revealed that the prevalence of FOF in Africa and Asia was high. Vo, et al. [169] reported that FOF among older adults Southeast Asia ranged from 21.6% to 88.2%, which was probably explained by a social environment that was unfriendly toward older adults, population aging, unbalanced economic conditions and a lack of familial support throughout urbanization. A previous study revealed that in developing countries, the high prevalence of FOF might be caused by low levels of education that prevent people from successfully managing FOF on their own, health caused by chronic diseases, inability to participate in social activities, and insufficient medical resources to properly manage both physical and psychological concerns [49], and inadequate service systems might have an impact on people’s ability to self-manage poor coping skills. Notably, although developed countries have better economic conditions, access to health care, educational opportunities, and social services than developing countries, some of them have high rates of FOF, such as the USA [16], Spain [28], Korea [20], and Japan [19]. It is likely that unhealthy lifestyles and diet habits lead to abnormal BMIs [54]. Ercan [171] reported that obesity could impact individuals’ posture and lead to balance problems, and obese females have higher FOF, higher activity restriction, and lower activity confidence than obese males. Earlier evidence demonstrated that older women with a high waist circumference had three times more likely to develop FOF than were those with a low waist circumference, which could alter the body’s center of gravity, further impair postural stability, and contribute to FOF [155]. However, another study showed that although BMI could slightly influence on body swing on unstable surfaces, obesity was not associated with FOF [171]. Furthermore, James [42] attempted to investigate the effect of the English language on fear of falling among Mexican-Americans in USA, but the results showed that not speaking or understanding English did not increase the incidence of FOF among those less than 80 years old, but it could affect activity restriction, to some extent.

Compared with community-dwelling residents, the prevalence of FOF was higher among those with chronic disease, especially patients with hip fracture [172], knee osteoarthritis [12], diabetes [173], etc. Previous studies have shown a high incidence of fear of falling in patients with hip fractures who underwent surgery involving knee replacement, total hip replacement or spinal surgery [37, 39], and FOF and cognitive impairment had a stronger impact on functional rehabilitation than did pain and depression [172]. In diabetic patients, symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, such as pain, feeling of ant walking, freezing, and burning, eventually impeded their ability to move and increased their likelihood of experiencing fear of falling [14]. Chronic pain has also been confirmed to m increase individuals’ susceptibility to FOF, and it plays a mediating role between FOF and poor physical performance [108]. Moreover, a qualitative study revealed that FOF gave patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) a sense of insecurity, vulnerability and danger in daily activities, and when facing PD-related symptoms, such as rigidity, gait freezing or balance problems, positive emotions would help them successfully cope with FOF [174]. However, cardiopulmonary pattern (hypertension) and cognitive impairment were not significantly associated with FOF in this study, which was not consistent with previous studies [30], in which the relationship between cognitive impairment and FOF decreased due to the effect of high social support. In addition, the meta-analysis of risk factors in this study indicated that regardless of the number of chronic diseases, they negatively effected on FOF. On the one hand, multiple comorbidities can affect the multiorgan function of older adults, and on the other hand, due to a reduction in metabolic function, the side effects of treating this disease with multiple drugs can negatively impact on health.Therefore, multidisciplinary cooperation, including rehabilitation, pharmacy, nutrition, psychology, etc., can help to prevent and reduce FOF among older adults.

Demographic characteristics (etc., age, female sex, low education level, living alone, history of falls) are the well-known, significant factors of FOF among older adults. Birhanie [49] reported that compared with individuals aged 60 to 70 years, those aged more than 70 years were four times more likely develop FOF, which was similar to our results. Previous studies have shown that females had a greater risk of fear of falling than men do, and a decrease in estrogen among older women could cause osteoporosis, bone hyperplasia and a decrease in limb muscle mass, further leading to a weakened musculoskeletal system [49]. Additionally, those with back pain, mental health conditions and neurological disorders are more likely to develop chronic disease [175]. Thiamwong [91] reported that the female sex and low education were closely associated with fear of falling, and the latter was important for preventing individuals from engaging in FOF education and learning how to prevent it. Moreover, according to a previous investigation, nearly 80% of older adults with a history of falling had a high fear of falling, especially among those who were over 85 years old, for whom nearly 95% of the participants were adults [7]. Frankenthal [84] indicated that the prevalence of FOF (69.8%) among people with a history of falls was higher than that among people without a history of falls (41.4%). Notably, living alone was also a significant factor for FOF, while being unmarried not. Older adults who lived alone had no assistance in daily activities and had no else help in dangerous situations. However, interestingly, De Roza [9] reported that older adults who were married status had greater FoF than those who were never married, which could be explained by the fact that those who never married might have developed great independence at an early age. In addition, because of the great independence, older adults who unmarried might have greater psychological resilience and better ability to cope well with FOF. Furthermore, we also found that the low social support was not significantly related to FOF in this study. Dierking [176] noted that social support had both positive and negative effects on people’s health, and that familial conflict could increase the risk of FOF, but friend support had a positive effect on preventing FOF. Hence, we suggest that actively addressing family conflicts and more social networks should be considered in FOF prevention programs.

Physical function, such as using walking aid, frailty, dependent daily activities, and balance problems, was significantly related to FOF, which was consistent with the findings of Gadhvi [168]. Birhanie [49] showed that older adults who used walking aids were fourteen timed more likely to developing FOF than those who did not use them. De Roza [9] noted that older adults who used quad sticks had greater FOF than did those who used umbrellas or walking sticks and that the use of walking aids was closely related to frailty, which subsequently impacted FOF. Furthermore, previous studies had reported that FOF and its related activity restriction were associated with impaired gait, balance problems, frailty, sarcopenia, depressive symptoms, and mortality [5, 144, 177]. Moreover, consistent with a previous study [49, 147], depression and anxiety were found to be the most common, significant psychological risk factors for FOF in this study. A meta-analysis by Gambaro et al. [6], revealed that FOF might play a mediating role between depression and falls. In addition, social culture and attitudes regarding aging-related changes were found to be strongly associated with FOF [178]. For example, one of the important reasons for the high prevalence of FOF among Korean older adults was the use of public transportation, such as buses or subway [48]. Therefore, we suggest that in addition to improving physical function, increasing balance confidence and changing the incorrect cognition of FOF, social infrastructure (e.g., walking paths, public transportation), home environments(e.g., using automated LED lighting), and social service policies to prevent and reduce FOF in older adults should be considered to increase the prevalence of FOF and create an age-friendly society.

This study also had several limitations. First, due to the involved observational studies, there might be some compounding factors, which might bias to the results. Notably, a large sample of 153 studies with 200,033 subjects from 38 countries could be advantageous for guaranteeing the consistency and universal applicability of the results. Second, high heterogeneity in this work was found, caused in part by the subjects from various nations, living conditions, cultures and lifestyles. Finally, only three studies from Africa were analyzed, probably because the work included only English studies, which may have left out some important evidence in other languages. Hence, more studies should pay more attention to FOF among older adults who speak different languages in the future.

Conclusion

This study as the first systematic review and meta-analysis provided substantial evidence that the global prevalence of FOF was high, and it was higher in developing countries than in developed countries, and higher in patients than in community residents. Twenty-eight potential risk factors, including demographic characteristics, physical function, chronic diseases and mental problems, were found a significant association with FOF. Policy-makers, health care providers and government officials should comprehensively evaluate the risk factors for FOF among older adults and formulate precise intervention measures to improve FOF based on the characteristics of different individuals. Firstly, multidisciplinary cooperation models should be established, including rehabilitation, psychology, pharmacology, etc, to help older patients normatively treat chronic diseases, strengthen drug safety management, and prevent drug abuse to reduce FOF. Secondly, a friendly living environment including improving exercise facilities and equipment and providing social support should be built to help older adults actively participate in social engagement. Finally, policy-makers should formulate the age-appropriate transformation system and intelligent health care system, optimize the health service model of older adults, actively develop the silver economy, and provide policy support and economic guarantee for promoting the physical and mental health of older adults.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kendrick D, Kumar A, Carpenter H, Zijlstra GA, Skelton DA, Cook JR, et al. Exercise for reducing fear of falling in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(11):CD009848. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009848.pub2.

Wu KY, Chen DR, Chan CC, Yeh YP, Chen HH. Fear of falling as a mediator in the association between social frailty and health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):421. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04144-1.

Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol. 1990;45(6):P239–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/45.6.p239.

Ayoubi F, Launay CP, Annweiler C, Beauchet O. Fear of falling and gait variability in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(1):14–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.06.020.

Lee TH, Kim W. Is fear of falling and the associated restrictions in daily activity related to depressive symptoms in older adults? Psychogeriatrics. 2021;21(3):304–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12664.

Gambaro E, Gramaglia C, Azzolina D, Campani D, Molin AD, Zeppegno P. The complex associations between late life depression, fear of falling and risk of falls. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;73:101532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101532.

Lee S, Hong GS. The predictive relationship between factors related to fear of falling and mortality among community-dwelling older adults in Korea: analysis of the Korean longitudinal study of aging from 2006 to 2014. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(12):1999–2005. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1663490.

Landers MR, Durand C, Powell DS, Dibble LE, Young DL. Development of a scale to assess avoidance behavior due to a fear of falling: the Fear of Falling Avoidance Behavior Questionnaire. Phys Ther. 2011;91(8):1253–65. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20100304.

De Roza JG, Ng DWL, Mathew BK, Jose T, Goh LJ, Wang C, et al. Factors influencing fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults in Singapore: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02883-1.

Savas S, Yenal S, Akcicek F. Factors related to falls and the fear of falling among elderly patients admitted to the emergency department. Turk J Geriatr. 2019;22(4):464–73. https://doi.org/10.31086/tjgeri.2020.125.

Nguyen LH, Thu VuG, Ha GH, Tat Nguyen C, Vu HM, Nguyen TQ, et al. Fear of falling among older patients admitted to hospital after falls in Vietnam: prevalence, associated factors and correlation with impaired health-related quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072493.

Zhang H, Si W, Pi H. Incidence and risk factors related to fear of falling during the first mobilisation after total knee arthroplasty among older patients with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(17–18):2665–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15731.

Visschedijk J, van Balen R, Hertogh C, Achterberg W. Fear of falling in patients with hip fractures: prevalence and related psychological factors. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(3):218–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.013.

Gupta G, Maiya GA, Bhat SN, Hande MH, Dillon L, Keay L. Fear of falling and functional mobility in elders with diabetic peripheral neuropathy in Coastal Karnataka, India: a hospital-based study. Curr Aging Sci. 2022;15(3):252–8. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874609815666220324153104.

Prell T, Uhlig M, Derlien S, Maetzler W, Zipprich HM. Fear of falling does not influence dual-task gait costs in people with Parkinson’s disease: a cross-sectional study. Sensors (Basel). 2022;22(5):2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22052029.

Yoshikawa A, Smith ML. Mediating role of fall-related efficacy in a fall prevention program. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(2):393–405. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.43.2.15.

Liu M, Hou T, Li Y, Sun X, Szanton SL, Clemson L, et al. Fear of falling is as important as multiple previous falls in terms of limiting daily activities: a longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):350. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02305-8.

Asai T, Misu S, Sawa R, Doi T, Yamada M. The association between fear of falling and smoothness of lower trunk oscillation in gait varies according to gait speed in community-dwelling older adults. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2017;14(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-016-0211-0.

Umegaki H, Uemura K, Makino T, Hayashi T, Cheng XW, Kuzuya M. Association of fear of falling with cognitive function and physical activity in older community-dwelling adults. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(1):99–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00410-2.

Choi K, Ko Y. Characteristics associated with fear of falling and activity restriction in South Korean older adults. J Aging Health. 2015;27(6):1066–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315573519.

Lee S, Oh E, Hong GS. Comparison of factors associated with fear of falling between older adults with and without a fall history. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5):982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050982.

Perez-Jara J, Olmos P, Abad MA, Heslop P, Walker D, Reyes-Ortiz CA. Differences in fear of falling in the elderly with or without dizzines. Maturitas. 2012;73(3):261–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.07.005.

Lavedán A, Viladrosa M, Jürschik P, Botigué T, Nuín C, Masot O, et al. Fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults: a cause of falls, a consequence, or both? PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194967. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194967.

Simsek H, Erkoyun E, Akoz A, Ergor A, Ucku R. Falls, fear of falling and related factors in community-dwelling individuals aged 80 and over in Turkey. Australas J Ageing. 2020;39(1):e16–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12673.

Bahat Öztürk G, Kılıç C, Bozkurt ME, Karan MA. Prevalence and associates of fear of falling among community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(4):433–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1535-9.

Alarcón T, González-Montalvo JI, Otero Puime A. Assessing patients with fear of falling. Does the method use change the results? A systematic review. Aten Primaria. 2009;41(5):262–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2008.09.019.

Chu CL, Liang CK, Chow PC, Lin YT, Tang KY, Chou MY, et al. Fear of falling (FF): psychosocial and physical factors among institutionalized older Chinese men in Taiwan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53(2):e232–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2010.12.018.

Esbrí-Víctor M, Huedo-Rodenas I, López-Utiel M, Navarro-López JL, Martínez-Reig M, Serra-Rexach JA, et al. Frailty and fear of falling: the FISTAC study. J Frailty Aging. 2017;6(3):136–40. https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2017.19.

Xie Q, Pei J, Gou L, Zhang Y, Zhong J, Su Y, et al. Risk factors for fear of falling in stroke patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(6):e056340. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056340.

Vo THM, Nakamura K, Seino K, Nguyen HTL, Van Vo T. Fear of falling and cognitive impairment in elderly with different social support levels: findings from a community survey in Central Vietnam. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01533-8.

Niederer D, Schmidt K, Vogt L, Egen J, Klingler J, Hübscher M, et al. Functional capacity and fear of falling in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Gait Posture. 2014;39(3):865–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.11.014.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z.

Chang SM. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) effective health care (EHC) program methods guide for comparative effectiveness reviews: keeping up-to-date in a rapidly evolving field. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1166–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.08.004.

Jannati R, Afshari M, Moosazadeh M, Allahgholipour SZ, Eidy M, Hajihoseini M. Prevalence of pulp stones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Med. 2019;12(2):133–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12331.

Boonpheng B, Thongprayoon C, Mao MA, Wijarnpreecha K, Bathini T, Kaewput W, et al. Risk of hip fracture in patients on hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Evid Based Med. 2019;12(2):98–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12341.

Goh HT, Nadarajah M, Hamzah NB, Varadan P, Tan MP. Falls and Fear of Falling After Stroke: A Case-Control Study. PM R. 2016;8(12):1173–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.05.012.

Damar HT, Bilik Ö, Baksi A, Akyil Ş. Examining the relationship between elderly patients’ fear of falling after spinal surgery and pain, kinesiophobia, anxiety, depression and the associated factors. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(5):1006–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.06.010.

Chen WC, Li YT, Tung TH, Chen C, Tsai CY. The relationship between falling and fear of falling among community-dwelling elderly. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(26):e2649210. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000026492.

Turhan Damar H, Bilik O, Karayurt O, Ursavas FE. Factors related to older patients’ fear of falling during the first mobilization after total knee replacement and total hip replacement. Geriatr Nurs. 2018;39(4):382–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.12.003.

Scarlett L, Baikie E, Chan SWY. Fear of falling and emotional regulation in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(12):1684–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1506749.

Tsonga T, Michalopoulou M, Kapetanakis S, Giovannopoulou E, Malliou P, Godolias G, et al. Risk factors for fear of falling in elderly patients with severe knee osteoarthritis before and one year after total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2016;24(3):302–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1602400306.

James EG, Conatser P, Karabulut M, Leveille SG, Hausdorff JM, Cote S, et al. Mobility limitations and fear of falling in non-English speaking older Mexican-Americans. Ethn Health. 2017;22(5):480–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2016.1244660.

Rivasi G, Kenny RA, Ungar A, Romero-Ortuno R. Predictors of Incident Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(5):615–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.020.

Lach HW. Incidence and risk factors for developing fear of falling in older adults. Public Health Nurs. 2005;22(1):45–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.22107.x.

Canever JB, Danielewicz AL, Leopoldino AAO, de Avelar NCP. Is the self-perception of the built neighborhood associated with fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;95:104395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2021.104395.

Canever JB, Danielewicz AL, Oliveira Leopoldino AA, Corseuil MW, de Avelar NCP. How Much Time in Sedentary Behavior Should Be Reduced to Decrease Fear of Falling and Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults? J Aging Phys Act. 2021;30(5):806–12. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2021-0175.

Murphy SL, Dubin JA, Gill TM. The development of fear of falling among community-living older women: predisposing factors and subsequent fall events. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(10):M943-7. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.10.m943.

Oh E, Hong GS, Lee S, Han S. Fear of falling and its predictors among community-living older adults in Korea. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(4):369–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1099034.

Birhanie G, Melese H, Solomon G, Fissha B, Teferi M. Fear of falling and associated factors among older people living in Bahir Dar City, Amhara, Ethiopia- a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):586. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02534-x.

Oh-Park M, Xue X, Holtzer R, Verghese J. Transient versus persistent fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults: incidence and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(7):1225–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03475.x.

Rochat S, Büla CJ, Martin E, Seematter-Bagnoud L, Karmaniola A, Aminian K, et al. What is the relationship between fear of falling and gait in well-functioning older persons aged 65 to 70 years? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(6):879–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.03.005.

Curcio CL, Gomez F, Reyes-Ortiz CA. Activity restriction related to fear of falling among older people in the Colombian Andes mountains: are functional or psychosocial risk factors more important? J Aging Health. 2009;21(3):460–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264308329024.

Chang HT, Chen HC, Chou P. Factors Associated with Fear of Falling among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in the Shih-Pai Study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150612. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150612.

Kumar A, Carpenter H, Morris R, Iliffe S, Kendrick D. Which factors are associated with fear of falling in community-dwelling older people? Age Ageing. 2014;43(1):76–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft154.

Singh T, Bélanger E, Thomas K. Is Fear of Falling the Missing Link to Explain Racial Disparities in Fall Risk? Data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Clin Gerontol. 2020;43(4):465–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1468377.

Noh HM, Roh YK, Song HJ, Park YS. Severe Fear of Falling Is Associated With Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: A 3-Year Prospective Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(12):1540–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.008.

Kim S, So WY. Prevalence and correlates of fear of falling in Korean community-dwelling elderly subjects. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48(11):1323–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2013.08.015.

Palagyi A, Ng JQ, Rogers K, Meuleners L, McCluskey P, White A, et al. Fear of falling and physical function in older adults with cataract: Exploring the role of vision as a moderator. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(10):1551–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12930.

Chang A, Ng JQ, Rogers K, Meuleners L, McCluskey P, White A, et al. Fear of falling and physical function in older adults with cataract: Exploring the role of vision as a moderator. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(10):1551–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12930.

Chang HT, Chen HC, Chou P. Fear of falling and mortality among community-dwelling older adults in the Shih-Pai study in Taiwan: A longitudinal follow-up study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(11):2216–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12968.

Boyd R, Stevens JA. Falls and fear of falling: burden, beliefs and behaviours. Age Ageing. 2009;38(4):423–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afp053.

Borges Sde M, Radanovic M, Forlenza OV. Fear of falling and falls in older adults with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2015;22(3):312–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2014.933770.

Perez-Jara J, Enguix A, Fernandez-Quintas JM, Gómez-Salvador B, Baz R, Olmos P, et al. Fear of falling among elderly patients with dizziness and syncope in a tilt setting. Can J Aging. 2009;28(2):157–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980809090151.

Visschedijk JH, Caljouw MA, Bakkers E, van Balen R, Achterberg WP. Longitudinal follow-up study on fear of falling during and after rehabilitation in skilled nursing facilities. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0158-1.

Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Romero LJ, Baumgartner RN, Garry PJ. Fear of falling and restriction of mobility in elderly fallers. Age Ageing. 1997;26(3):189–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/26.3.189.

Park JH, Cho H, Shin JH, Kim T, Park SB, Choi BY, et al. Relationship among fear of falling, physical performance, and physical characteristics of the rural elderly. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(5):379–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000009.

Austin N, Devine A, Dick I, Prince R, Bruce D. Fear of falling in older women: a longitudinal study of incidence, persistence, and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(10):1598–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01317.x.

Auais M, Alvarado BE, Curcio CL, Garcia A, Ylli A, Deshpande N. Fear of falling as a risk factor of mobility disability in older people at five diverse sites of the IMIAS study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:147–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.05.012.

Mann R, Birks Y, Hall J, Torgerson D, Watt I. Exploring the relationship between fear of falling and neuroticism: a cross-sectional study in community-dwelling women over 70. Age Ageing. 2006;35(2):143–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afj013.

Canever JB, de Souza Moreira B, Danielewicz AL, de Avelar NCP. Are multimorbidity patterns associated with fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults? BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02889-9.

Payette MC, Bélanger C, Benyebdri F, Filiatrault J, Bherer L, Bertrand JA, et al. The Association between Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Subthreshold Anxiety Symptoms and Fear of Falling among Older Adults: Preliminary Results from a Pilot Study. Clin Gerontol. 2017;40(3):197–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2017.1296523.

Jellesmark A, Herling SF, Egerod I, Beyer N. Fear of falling and changed functional ability following hip fracture among community-dwelling elderly people: an explanatory sequential mixed method study. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(25):2124–31. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.673685.

Uemura K, Shimada H, Makizako H, Yoshida D, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, et al. A lower prevalence of self-reported fear of falling is associated with memory decline among older adults. Gerontology. 2012;58(5):413–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000336988.

Howland J, Lachman ME, Peterson EW, Cote J, Kasten L, Jette A. Covariates of fear of falling and associated activity curtailment. Gerontologist. 1998;38(5):549–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/38.5.549.

Clemson L, Kendig H, Mackenzie L, Browning C. Predictors of injurious falls and fear of falling differ: an 11-year longitudinal study of incident events in older people. J Aging Health. 2015;27(2):239–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264314546716.

Zijlstra GA, van Haastregt JC, van Eijk JT, van Rossum E, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fear of falling, and associated avoidance of activity in the general population of community-living older people. Age Ageing. 2007;36(3):304–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afm021.

Jefferis BJ, Iliffe S, Kendrick D, Kerse N, Trost S, Lennon LT, et al. How are falls and fear of falling associated with objectively measured physical activity in a cohort of community-dwelling older men? BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:114. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-114.

Franzoni S, Rozzini R, Boffelli S, Frisoni GB, Trabucchi M. Fear of falling in nursing home patients. Gerontology. 1994;40(1):38–44. https://doi.org/10.1159/000213573.

Bruce DG, Devine A, Prince RL. Recreational physical activity levels in healthy older women: the importance of fear of falling. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):84–9. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50012.x.

Rossat A, Beauchet O, Nitenberg C, Annweiler C, Fantino B. Risk factors for fear of falling: a cross-sectional population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1304–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02299.x.

Kressig RW, Wolf SL, Sattin RW, O’Grady M, Greenspan A, Curns A, et al. Associations of demographic, functional, and behavioral characteristics with activity-related fear of falling among older adults transitioning to frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(11):1456–62. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911237.x.

Kornfield SL, Lenze EJ, Rawson KS. Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Association with Fear of Falling After Hip Fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(6):1251–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14771.

Viljanen A, Kulmala J, Rantakokko M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Rantanen T. Fear of falling and coexisting sensory difficulties as predictors of mobility decline in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(11):1230–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gls134.

Frankenthal D, Saban M, Karolinsky D, Lutski M, Sternberg S, Rasooly I, Laxer I, Zucker I. Falls and fear of falling among Israeli community-dwelling older people: a cross-sectional national survey. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2021;10(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-021-00464-y.

Park JI, Yang JC, Chung S. Risk Factors Associated with the Fear of Falling in Community-Living Elderly People in Korea: Role of Psychological Factors. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14(6):894–9. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2017.14.6.894.

Mane AB, Sanjana T, Patil PR, Sriniwas T. Prevalence and correlates of fear of falling among elderly population in urban area of Karnataka, India. J Midlife Health. 2014;5(3):150–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-7800.141224.

Goldberg A, Sucic JF, Talley SA. The angiotensin-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism interacts with fear of falling in relation to stepping speed in community-dwelling older adults. Physiother Theory Pract. 2023;39(9):1981–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2022.2056861.

Wang QX, Ye ZM, Wu WJ, Zhang Y, Wang CL, Zheng HG. Association of Fear of Falling With Cognition and Physical Function in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Nurs Res. 202201;71(5):387–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000608.

Zheng X, Wan Q, Jin X, Huang H, Chen J, Li Y, et al. Fall efficacy and influencing factors among Chinese community-dwelling elders with knee osteoarthritis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2016;22(3):275–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12423.

Bertera EM, Bertera RL. Fear of falling and activity avoidance in a national sample of older adults in the United States. Health Soc Work. 2008;33(1):54–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/33.1.54.

Thiamwong L, Suwanno J. Fear of falling and related factors in a community-based study of people 60 years and older in Thailand. Int J Gerontol. 2017;11(2):80–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijge.2016.06.003.

Viljanen A, Kulmala J, Rantakokko M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Rantanen T. Accumulation of sensory difficulties predicts fear of falling in older women. J Aging Health. 2013;25(5):776–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264313494412.

Taghadosi M, Motaharian E, Gilasi H. Fear of Falling and Related Factors in Older Adults in the City of Kashan in 2017. ARCHIVES OF TRAUMA RESEARCH. 2018;7(2):50–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/atr.atr_27_18.

Vitorino LM, Marques-Vieira C, Low G, Sousa L, Cruz JP. Fear of falling among Brazilian and Portuguese older adults. Int J Older People Nurs. 2019;14(2):e12230. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12230

Topuz S, De Schepper J, Ulger O, Roosen P. Do Mobility and Life Setting Affect Falling and Fear of Falling in Elderly People? Top Geriatr Rehab. 2014;30(3):223–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/TGR.0000000000000031.

Sharaf AY, Ibrahim HS. Physical and psychosocial correlates of fear of falling: among older adults in assisted living facilities. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(12):27–35. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20081201-07.

Chang NT, Chi LY, Yang NP, Chou P. The impact of falls and fear of falling on health-related quality of life in Taiwanese elderly. J Community Health Nurs. 2010;27(2):84–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370011003704958.

Ivanovic S, Trgovcevic S. Risk factors for developing fear of falling in the elderly in Serbia. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2018;75(8):764–72. https://doi.org/10.2298/VSP160620369I.

Kulkarni S, Gadkari R, Nagarkar A. Risk factors for fear of falling in older adults in India. J Public Health-Heidelberg. 2020;28(2):123–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01061-9.

Sitdhiraksa N, Piyamongkol P, Chaiyawat P, Chantanachai T, Ratta-Apha W, Sirikunchoat J, et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Thai Elderly. Gerontology. 2021;67(3):276–80. https://doi.org/10.1159/000512858.

Deshpande N, Metter EJ, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Windham BG, Ferrucci L. Psychological, physical, and sensory correlates of fear of falling and consequent activity restriction in the elderly: the InCHIANTI study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(5):354–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31815e6e9b.

Brodowski H, Strutz N, Mueller-Werdan U, Kiselev J. Categorizing fear of falling using the survey of activities and fear of falling in the elderly questionnaire in a cohort of hospitalized older adults: A cross-sectional design. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;126:104152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104152.

Malini FM, Lourenço RA, Lopes CS. Prevalence of fear of falling in older adults, and its associations with clinical, functional and psychosocial factors: the Frailty in Brazilian Older People-Rio de Janeiro study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(3):336–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12477.

Tomita Y, Arima K, Tsujimoto R, Kawashiri SY, Nishimura T, Mizukami S, et al. Prevalence of fear of falling and associated factors among Japanese community-dwelling older adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(4):e9721. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000009721.

Lim JY, Jang SN, Park WB, Oh MK, Kang EK, Paik NJ. Association between exercise and fear of falling in community-dwelling elderly Koreans: results of a cross-sectional public opinion survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(6):954–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.041.

Doi T, Ono R, Ono K, Yamaguchi R, Makiura D, ... Hirata S. The Association between Fear of Falling and Physical Activity in Older Women. J Phys Ther Sci. 2012;24(9):859–62. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.24.859.

Murphy SL, Williams CS, Gill TM. Characteristics associated with fear of falling and activity restriction in community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):516–20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50119.x.

Nawai A, Phongphanngam S, Khumrungsee M, Radabutr M. Chronic pain as a moderator between fear of falling and poor physical performance among community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2022;45:140–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.03.012.

Drummond FMM, Lourenço RA, Lopes CS. Association between fear of falling and spatial and temporal parameters of gait in older adults: the FIBRA-RJ study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;13(2):407–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-021-00601-5.

Kurkova P, Kisvetrova H, Horvathova M, Tomanova J, Bretsnajdrova M, ... Herzig R. Fear of falling and physical performance among older Czech adults. Fam Med Prim Care Rev. 2020;22(1):32–5. https://doi.org/10.5114/fmpcr.2020.92503.

Boltz M, Resnick B, Capezuti E, Shuluk J. Activity restriction vs. self-direction: hospitalised older adults' response to fear of falling. Int J Older People Nurs. 2014;9(1):44–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12015. Epub 2013 Jan 7.

Brustio PR, Magistro D, Zecca M, Liubicich ME, Rabaglietti E. Fear of falling and activities of daily living function: mediation effect of dual-task ability. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(6):856–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1318257.

Hewston P, Garcia A, Alvarado B, Deshpande N. Fear of Falling in Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: The IMIAS Study. Can J Aging. 2018;37(3):261–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S071498081800020X.

Kakhki AD, Kouchaki L, Bayat ZS. Fear of Falling and Related Factors Among Older Adults With Hypertension in Tehran, Iran. Iran Heart J. 2018;19(4):33–9.

Makino K, Lee S, Bae S, Chiba I, Harada K, Katayama O, et al. Prospective Associations of Physical Frailty With Future Falls and Fear of Falling: A 48-Month Cohort Study. Phys Ther. 2021;101(6):pzab059. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab059.

Akosile CO, Igwemmadu CK, Okoye EC, Odole AC, Mgbeojedo UG, Fabunmi AA, et al. Physical activity level, fear of falling and quality of life: a comparison between community-dwelling and assisted-living older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01982-1.

Vitorino LM, Teixeira CA, Boas EL, Pereira RL, Santos NO, Rozendo CA. Fear of falling in older adults living at home: associated factors. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2017;51:e03215. English, Portuguese. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-220X2016223703215.

Teixeira L, Araújo L, Duarte N, Ribeiro O. Falls and fear of falling in a sample of centenarians: the role of multimorbidity, pain and anxiety. Psychogeriatrics. 2019;19(5):457–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12423.

Gottschalk S, König HH, Schwenk M, Jansen CP, Nerz C, Becker C, et al. Mediating factors on the association between fear of falling and health-related quality of life in community-dwelling German older people: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):401. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01802-6.

Shahid S, Tariq MI, Ramzan T. Correlation of fall efficacy scale and Hendrich fall risk model in elder population of Rawalpindi-Islamabad. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020;70(11):1938–40. https://doi.org/10.5455/JPMA.21505.

Liu JY. Fear of falling in robust community-dwelling older people: results of a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(3–4):393–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12613.

Sakurai R, Montero-Odasso M, Suzuki H, Ogawa S, Fujiwara Y. Motor Imagery Deficits in High-Functioning Older Adults and Its Impact on Fear of Falling and Falls. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(9):e228–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glab073.

Du L, Zhang X, Wang W, He Q, Li T, Chen S, et al. Associations between objectively measured pattern of physical activity, sedentary behavior and fear of falling in Chinese community-dwelling older women. Geriatr Nurs. 2022;46:80–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.05.001.

Park GR, Kim J. Coexistent physical and cognitive decline and the development of fear of falling among Korean older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5705.

Arfken CL, Lach HW, Birge SJ, Miller JP. The prevalence and correlates of fear of falling in elderly persons living in the community. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(4):565–70. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.84.4.565.

Chou K, Chi I. The temporal relationship between falls and fear-of-falling among Chinese older primary-care patients in Hong Kong. Ageing Soc. 2007;27:181–93. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X06005393.

Arani SJ, Rezaei M, Dianati M, Atoof F. The association between fear of falling and functional tests in older adults with diabetes mellitus. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2020;9(3):163–70. https://doi.org/10.4103/nms.nms_86_19.

Ren P, Zhang X, Du L, Pan Y, Chen S, He Q. Reallocating Time Spent in Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior and Its Association with Fear of Falling: Isotemporal Substitution Model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(5):2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052938.

Katsumata Y, Arai A, Tomimori M, Ishida K, Lee RB, Tamashiro H. Fear of falling and falls self-efficacy and their relationship to higher-level competence among community-dwelling senior men and women in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11(3):282–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00679.x.

Friedman SM, Munoz B, West SK, Rubin GS, Fried LP. Falls and fear of falling: which comes first? A longitudinal prediction model suggests strategies for primary and secondary prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(8):1329–35. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50352.x.

Löppönen A, Karavirta L, Koivunen K, Portegijs E, Rantanen T, Finni T, et al. Association Between Free-Living Sit-to-Stand Transition Characteristics, and Lower-Extremity Performance, Fear of Falling, and Stair Negotiation Difficulties Among Community-Dwelling 75 to 85-Year-Old Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77(8):1644–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glac071.

Lach HW, Lozano AJ, Hanlon AL, Cacchione PZ. Fear of falling in sensory impaired nursing home residents. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(3):474–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1537359.

Van Haastregt JC, Zijlstra GA, van Rossum E, van Eijk JT, Kempen GI. Feelings of anxiety and symptoms of depression in community-living older persons who avoid activity for fear of falling. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):186–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181591c1e.

Schroeder O, Schroeder J, Fitschen-Oestern S, Besch L, Seekamp A. Effectiveness of autonomous home hazard reduction on fear of falling in community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(6):1754–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17725.

Sakurai R, Fujiwara Y, Yasunaga M, Suzuki H, Kanosue K, Montero-Odasso M, et al. Association between Hypometabolism in the Supplementary Motor Area and Fear of Falling in Older Adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:251. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00251.

Aburub AS, P Phillips S, Curcio CL, Guerra RO, Auais M. Fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults diagnosed with cancer: A report from the International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS). J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(4):603–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.09.001.

Gagnon N, Flint AJ, Naglie G, Devins GM. Affective correlates of fear of falling in elderly persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(1):7–14. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.1.7.

Visschedijk JH, Caljouw MA, van Balen R, Hertogh CM, Achterberg WP. Fear of falling after hip fracture in vulnerable older persons rehabilitating in a skilled nursing facility. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46(3):258–63. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1264.

Jaatinen R, Luukkaala T, Hongisto MT, Kujala MA, Nuotio MS. Factors associated with and 1-year outcomes of fear of falling in a geriatric post-hip fracture assessment. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(9):2107–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02159-z.

Martínez-Arnau FM, Prieto-Contreras L, Pérez-Ros P. Factors associated with fear of falling among frail older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(5):1035–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.06.007.

Pohl P, Ahlgren C, Nordin E, Lundquist A, Lundin-Olsson L. Gender perspective on fear of falling using the classification of functioning as the model. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(3):214–22. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.914584.

Trevisan C, Zanforlini BM, Maggi S, Noale M, Limongi F, De Rui M, et al. Judgment Capacity, Fear of Falling, and the Risk of Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Progetto Veneto Anziani Longitudinal Study. Rejuvenation Res. 2020;23(3):237–44. https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2019.2197.

Choi K, Jeon GS, Cho SI. Prospective Study on the Impact of Fear of Falling on Functional Decline among Community Dwelling Elderly Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(5):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14050469.

Merchant RA, Chen MZ, Wong BLL, et al. Relationship between fear of falling, fear-related activity restriction, frailty, and sarcopenia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2602–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16719.

Asai T, Oshima K, Fukumoto Y, Yonezawa Y, Matsuo A, Misu S. The association between fear of falling and occurrence of falls: a one-year cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):393. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03018-2.

Yang R, Pepper GA. Is fall self-efficacy an independent predictor of recurrent fall events in older adults? Evidence from a 1-year prospective study. Res Nurs Health. 2020;43(6):602–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.22084.

Freiberger E, Fabbietti P, Corsonello A, Lattanzio F, Artzi-Medvedik R, Kob R, Melzer I, SCOPE consortium, Britting S. Transient versus stable nature of fear of falling over 24 months in community-older persons with falls- data of the EU SCOPE project on Kidney function. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):698. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03357-0.

Peterson E, Howland J, Kielhofner G, Lachman ME, Assmann S, Cote J, ... Jette A. Falls self-efficacy and occupational adaptation among elders. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 1999;16(1-2):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1300/J148v16n01_01.

Sawa R, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Nakakubo S, Kurita S, Kiuchi Y, et al. Overlapping status of frailty and fear of falling: an elevated risk of incident disability in community-dwelling older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2023;35(9):1937–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-023-02474-z.

You L, Guo L, Li N, Zhong J, Er Y, Zhao M. Association between multimorbidity and falls and fear of falling among older adults in eastern China: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1146899. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1146899.

Garbin AJ, Fisher BE. Examining the Role of Physical Function on Future Fall Likelihood in Older Adults With a Fear of Falling, With and Without Activity Restriction. J Aging Health. 2023:8982643231170308. https://doi.org/10.1177/08982643231170308.

Garbin AJ, Fisher BE. The Interplay Between Fear of Falling, Balance Performance, and Future Falls: Data From the National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2023;46(2):110–5. https://doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0000000000000324.

Liu K, Peng W, Ge S, Li C, Zheng Y, Huang X, et al. Longitudinal associations of concurrent falls and fear of falling with functional limitations differ by living alone or not. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1007563. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1007563.

Scheffers-Barnhoorn MN, Haaksma ML, Achterberg WP, Niggebrugge AH, van der Sijp MP, van Haastregt JC, et al. Course of fear of falling after hip fracture: findings from a 12-month inception cohort. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e068625. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068625

Prado BH, de Souza LF, Canever JB, Moreira BS, Danielewicz AL, Avelar NCP. Is waist circumference associated with fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults? A cross-sectional study. Geriatr Nurs. 2023;50:203–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.01.010.

Zhang Y, Ye M, Wang X, Wu J, Wang L, Zheng G. Age differences in factors affecting fear of falling among community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. Geriatr Nurs. 2023;49:74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.11.011.

Chu SF, Wang HH. Outcome Expectations and Older Adults with Knee Osteoarthritis: Their Exercise Outcome Expectations in Relation to Perceived Health, Self-Efficacy, and Fear of Falling. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;11(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010057.

Siefkas AC, McCarthy EP, Leff B, Dufour AB, Hannan MT. Social Isolation and Falls Risk: Lack of Social Contacts Decreases the Likelihood of Bathroom Modification Among Older Adults With Fear of Falling. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41(5):1293–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211062373.

Korenhof SSA, van Grieken AA, Franse CCB, Tan SSSS, Verma AA, Alhambra TT, et al. The association of fear of falling and physical and mental Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) among community-dwelling older persons; a cross-sectional study of Urban Health Centres Europe (UHCE). BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):291. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04004-y.

Dos Santos EPR, Ohara DG, Patrizzi LJ, de Walsh IAP, Silva CFR, da Silva Neto JR, et al. Investigating Factors Associated with Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older Adults through Structural Equation Modeling Analysis: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(2):545. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020545.

DiGuiseppi CG, Hyde HA, Betz ME, Scott KA, Eby DW, Hill LL, et al. Association of falls and fear of falling with objectively-measured driving habits among older drivers: LongROAD study. J Safety Res. 2022;83:96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2022.08.007.

Badrasawi M, Hamdan M, Vanoh D, Zidan S, ALsaied T, Muhtaseb TB. Predictors of fear of falling among community-dwelling older adults: Cross-sectional study from Palestine. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0276967. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276967.

McKay MA, Mensinger JL, O’Connor M, Utz M, Costello A, Leveille S. Self-reported symptom causes of mobility difficulty contributing to fear of falling in older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(12):3089–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02253-2.

Luo Y, Miyawaki CE, Valimaki MA, Tang S, Sun H, Liu M. Symptoms of anxiety and depression predicting fall-related outcomes among older Americans: a longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):749. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03406-8.

Shiratsuchi D, Makizako H, Nakai Y, Bae S, Lee S, Kim H, et al. Associations of fall history and fear of falling with multidimensional cognitive function in independent community-dwelling older adults: findings from ORANGE study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(12):2985–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02235-4.

Turhan Damar H, Demir Barutcu C. Relationship between hospitalised older people's fear of falling and adaptation to old age, quality of life, anxiety and depression. Int J Older People Nurs. 2022;17(6):e12467. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12467.

Dhar M, Kaeley N, Mahala P, Saxena V, Pathania M. The Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Fear of Fall in the Elderly: A Hospital-Based, Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 2022;14(3):e23479. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.23479.

Vo MTH, Thonglor R, Moncatar TJR, Han TDT, Tejativaddhana P, Nakamura K. Fear of falling and associated factors among older adults in Southeast Asia: a systematic review. Public Health. 2023;222:215–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.08.012.

Gadhvi C, Bean D, Rice D. A systematic review of fear of falling and related constructs after hip fracture: prevalence, measurement, associations with physical function, and interventions. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):385. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03855-9.

World Health Organization. Ageing and health. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed 18 Feb 2024.

Ercan S, Baskurt Z, Baskurt F, Cetin C. Balance disorder, falling risks and fear of falling in obese individuals: cross-sectional clinical research in Isparta. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020;70(1):17–23. https://doi.org/10.5455/JPMA.293668.

Oude Voshaar RC, Banerjee S, Horan M, Baldwin R, Pendleton N, Proctor R, et al. Fear of falling more important than pain and depression for functional recovery after surgery for hip fracture in older people. Psychol Med. 2006;36(11):1635–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706008270.

Inayati A, Lee BO, Wang RH, et al. Determinants of fear of falling in older adults with diabetes. Geriatr Nurs. 2022;46:7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.04.017.

Jonasson SB, Nilsson MH, Lexell J, Carlsson G. Experiences of fear of falling in persons with Parkinson’s disease - a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0735-1. Published 2018 Feb 6.

Uddin S, Wang S, Khan A, Lu H. Comorbidity progression patterns of major chronic diseases: the impact of age, gender and time-window. Chronic Illn. 2023;19(2):304–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/17423953221087647.

Dierking L, Markides K, Al Snih S, Kristen Peek M. Fear of falling in older Mexican Americans: a longitudinal study of incidence and predictive factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2560–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14496.

Yang JM, Kim JH. Association between activity restriction due to fear of falling and mortality: results from the Korean longitudinal study of aging. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2022;22(2):168–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14336.

Rico CLV, Curcio CL. Fear of falling and environmental factors: a scoping review. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2022;26(2):83–93. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.22.0016.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to thank all authors of the included studies in this study.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: Y.L. and W.X.; Data collection: W.X. and D.W; Data analysis: Y.L.and W.X.; Manuscript writing: W.X. and Y.L.; Revisions for important intellectual content: W.R., X.L., and R.W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, W., Wang, D., Ren, W. et al. The global prevalence of and risk factors for fear of falling among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 24, 321 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04882-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04882-w