Abstract

Background

The share of people over 80 years in the European Union is estimated to increase two-and-a-half-fold from 2000 to 2100. A substantial share of older persons experiences fear of falling. This fear is partly associated with a fall in the recent past. Because of the associations between fear of falling, avoiding physical activity, and the potential impact of those on health, an association between fear of falling and low health-related quality of life, is suggested. This study examined the association of fear of falling with physical and mental Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) among community-dwelling older persons in five European countries.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted using baseline data of community-dwelling persons of 70 years and older participating in the Urban Health Centers Europe project in five European countries: United Kingdom, Greece, Croatia, the Netherlands and Spain. This study assessed fear of falling with the Short Falls Efficacy Scale-International and HRQoL with the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey. The association between low, moderate or high fear of falling and HRQoL was examined using adjusted multivariable linear regression models.

Results

Data of 2189 persons were analyzed (mean age 79.6 years; 60.6% females). Among the participants, 1096 (50.1%) experienced low fear of falling; 648 (29.6%) moderate fear of falling and 445 (20.3%) high fear of falling. Compared to those who reported low fear of falling in multivariate analysis, participants who reported moderate or high fear of falling experienced lower physical HRQoL (β = -6.10, P < 0.001 and β = -13.15, P < 0.001, respectively). In addition, participants who reported moderate or high fear of falling also experienced lower mental HRQoL than those who reported low fear of falling (β = -2.31, P < 0.001 and β = -8.80, P < 0.001, respectively).

Conclusions

This study observed a negative association between fear of falling and physical and mental HRQoL in a population of older European persons. These findings emphasize the relevance for health professionals to assess and address fear of falling. In addition, attention should be given to programs that promote physical activity, reduce fear of falling, and maintain or increase physical strength among older adults; this may contribute to physical and mental HRQoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Europe holds a relatively high proportion of persons over 65 years old [1]. It is estimated that the share of those aged 80 years or older in the European Union will increase two–and-a-half-fold between 2020 and 2100, i.e. from 5.9% to 14.6% [2]. Approximately 30% of community-dwelling persons over 65 years of age experienced a fall during the past year [3,4,5,6]. Related to this, a substantial part of community-dwelling older persons experience fear of falling [1, 5,6,7,8]. As reported in the literature, the prevalence of fear of falling ranges from 3 to 85% [6, 7, 9]. The reported prevalence depends on the specific study sample, the number of previous falls in the study population, and the specific definition or measurement tool used [6, 7, 9,10,11].

Fear of falling is defined as the ongoing concern about falling that could ultimately lead to activity avoidance [12]. And is also associated with incident disability [13] and increased mortality as well [14]. Fear of falling is suggested to have a bidirectional relationship with falling itself; fear of falling may be a predictor of falling, and vice versa; falling has been reported to be associated with subsequent fear of falling [15]. In a longitudinal study by Friedman et al., of the participants without fear of falling at baseline, persons who experienced a fall were twice as likely to experience fear of falling at follow-up compared to persons who had not experienced a fall [15]. Persons who experience fear of falling may develop an aversion regarding physical activity behaviors, leading to a decline in physical health [15]. Therefore, fear of falling is considered a risk factor for future falls [6, 15, 16]. In addition, fear of falling also showed a positive association with frailty [17].

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is considered an important outcome on healthy ageing in geriatric medicine and public health [18]. HRQoL is defined as a multidimensional and subjective measure of well-being in relation to health, embodying the appraisal of physical, mental and social well-being [19, 20]. Because of the associations between fear of falling, tendency to avoid physical activity, and potential impact of those on health, an association between fear of falling and low health-related quality of life, is suggested [9]. Landi et al. have shown that disability is an important influence for risk of death in older people [21]. In addition, Schoene et al. have recommended studying the impact of fear of falling on HRQoL in ageing populations [22]. Nevertheless, thus far, only a few studies have studied these associations [8, 22]. Insight into the association between fear of falling and HRQoL may inform healthcare professionals on the need to support older persons in maintaining healthy [22].

This study aimed to investigate the associations between fear of falling and HRQoL, corrected for previous falls, among community-dwelling older persons aged 70 years and over in Europe. We explored interaction by age, gender, country, level of education, living situation, physical activity behaviors, experienced falls in the previous 12 months and multi-morbidity. Following the literature, the hypothesis was that the association between fear of falling and HRQoL would be observed among participants that were women [9, 23], older [9], lower educated [9, 24], living alone [24] and physically active once or less per week [23, 25]. With regard to country, we hypothesized that there may be a different association between countries [26].

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study used baseline data from the Urban Health Centres Europe (UHCE) project for secondary analysis. The evaluation design and effectiveness of the UHCE study, a study regarding anticipatory preventive care for older persons, were described by Franse et al. (2017) [26, 27]. This project was implemented in five European cities (Greater Manchester, United Kingdom; Pallini, Greece; Rijeka, Croatia; Rotterdam, the Netherlands; and Valencia, Spain). 2325 UHCE participants were enrolled between May 2015 and June 2017. Participants’ inclusion criteria were: aged 70 years and older, community-dwelling and able to participate in the study for at least six months, according to their physician. Exclusion criteria were: not fluent in the local language and unable to cognitively assess the risks and benefits of participation. Data were obtained by self-reported questionnaires. All participants provided written informed consent. Ethical committee procedures have been followed in all cities and institutions involved, and approval has been provided [27].

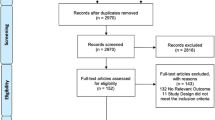

The current study used baseline data (2325 participants) from the UHCE project. Participants with missing data on age, gender, fear of falling or HRQoL were excluded from the analyses (N = 136). Thus, the population for analysis consisted of 2189 participants (see Suppl. Figure 1).

Measures

Fear of falling

Fear of falling was assessed by the Falls Efficacy Scale International Short (Short FES-I), which has been shown to have adequate validity in European populations (Cronbach’s alpha 0.92, intra-class coefficient 0.83) [28,29,30]. The Short FES-I assesses fear of falling concerning seven activities: going up and down stairs, getting dressed or undressed, taking a bath or shower, getting in or out of a chair, going up or down stairs, reaching for something above your head or on the ground, walking up or down a slope and going out to a social event; and has four possible answer categories: not at all concerned (1 point), somewhat concerned (2 points), fairly concerned (3 points) and very concerned (4 points). The final scores of the Short FES-I range between 7 and 28, whereby a score of 7–8 corresponds to low fear of falling, and scores of 9–13 and 14–28 correspond to moderate and high fear of falling, respectively [29].

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

The 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) version 2 was used to assess physical and mental HRQoL; it has shown to be a valid instrument for assessing HRQoL in various European countries in adult populations [31, 32]. The questionnaire consists of eight domains: bodily pain (1 item), vitality (1), physical functioning (2), physical role functioning (2), emotional role functioning (2), mental health (2), social functioning (1) and general health (1). The raw SF-12 scores were first transformed to provide scores ranging from 0 (the worst) to 100 (the best). After that, the physical and mental component summary scores (PCS and MCS) were calculated; these are standard scores with a mean value of 50 points and a standard deviation of 10 points [31].

Covariates

Socio-demographic factors

The socio-demographic factors age, gender, country, level of education and living situation (alone/ not alone) were assessed. The level of education was divided into three groups according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). ISCED level 0–1 was defined as ‘primary or lower’; ISCED level 2–5 was defined as ‘secondary’, and ISCED level 6–8 was defined as ‘tertiary’ [33].

Lifestyle and general health factors

Alcohol risk (yes/ no), physical activity (once a week or less/ more than once a week), smoking (yes/ no) and multi-morbidity (< 2 or ≥ 2 chronic conditions) were assessed [34]. Smoking was assessed with one item that asked whether a person smoked at present. Alcohol risk was assessed with the AUDIT-C, which contains three items to screen high-risk alcohol use on a scale from 0 (lowest risk) to 12 (highest risk) [35]. A score of at least 4 for men and 3 for women is considered hazardous drinking or active alcohol use disorder and therefore defined as ‘alcohol risk’ [35]. Multi-morbidity was defined as having (had) at least two out of 14 chronic conditions [36]: heart attack, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, high blood cholesterol, asthma, arthritis, osteoporosis, chronic lung disease, cancer or malignant tumor, stomach or duodenal ulcer, Parkinson’s disease, cataract and hip fracture or femoral fracture [37].

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics of the covariates, socio-demographic and lifestyle factors were determined and stratified by fear of falling category. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test for continuous variables (age) and Pearson’s chi-squared tests for categorical variables (all other variables) was conducted to compare the low, moderate and high fear of falling groups with each other on the covariates. Differences in HRQoL scores were compared between participants with moderate or high and low fear of falling. Cohen’s effect size estimations (d) were calculated, which relate the difference in mean scores to the dispersion of the scores: [Mean1 − Mean2]/(σpooled); where pooled standard deviation was calculated as σpooled = √[(σ12 + σ22) / 2]. Following Cohen's suggested guidelines, 0.20 ≤ d < 0.50 was taken to indicate a small effect size, 0.50 ≤ d < 0.80 a moderate effect size, and d ≥ 0.8 a large effect size [38].

Age, gender, country, level of education, living situation, alcohol risk, physical activity, smoking, and multi-morbidity of included versus excluded participants were compared via Pearson’s chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Multivariable linear regression analyses were performed to examine the associations between fear of falling and physical and mental HRQoL. First, associations were tested for fear of falling (low, moderate, high) and physical or mental HRQoL (crude model). Second, socio-demographic and lifestyle factors were added to this model (adjusted model). Beta coefficients were calculated for; and presented with 95%-confidence intervals (CIs). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Similarly, the association was also tested between continuous fear of falling scores and physical and mental HRQoL. (Suppl. Table 1).

We performed linearity tests, normality of residuals with kernel density plots and tests for multicollinearity with variance inflation factors.

Finally, the interaction between the fear of falling score (continuous) and age, gender, country, level of education, living situation, alcohol risk, physical activity and multi-morbidity was evaluated by adding interaction terms to the adjusted models (Suppl. Table 2). Models were run separately for mental and physical HRQoL. The 2-sided significance threshold, after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing, was set at 0.05 (original P-value) / 18 (number of tests performed) = P = 0.0028. Stratified linear regression analyses were run for statistically significant interaction terms. (Suppl. Tables 3, 4 and 5).

All analyses were performed with SPSS version 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

The mean age of the participants was 79.7 (SD 5.6) years; 60.6% were female. Overall, 50.1% reported a ‘low’, 29.6% a ‘moderate’, and 20.3% a ‘high’ level of fear of falling; the mean score on the Short FES-I was 10.6 (SD 4.9). The mean physical and mental HRQoL scores were 41.8 (SD 12.1) and 50.2 (SD 10.7), respectively. Mean physical and mental HRQoL scores were lower in the subgroups who reported ‘moderate’ and ‘high’ fear of falling compared to those who reported ‘low’ fear of falling (P < 0.001). The percentage of participants who experienced a fall in the last 12 months was higher in the subgroup who reported ‘high’ or ‘moderate’ fear of falling compared to those who reported ‘low’ fear of falling. Cohen’s d effect size between participants of the ‘low’ and ‘high’ fear of falling subgroups for physical and mental HRQoL was calculated at d ≥ 0.80. (Table 1).

All variance inflation factors were lower than four, suggesting low multicollinearity. No violation of basic assumptions for regression was found.

Comparison of included and excluded participants

Participants who were excluded (n = 136) were, compared to participants who were included (n = 2189), relatively older (80.5 versus 79.7 years old), more often smokers and more often from Greece or the Netherlands and less often from the United Kingdom, Croatia or Spain; all P < 0.02. Included and excluded participants showed no significant differences for the variables gender, level of education, living situation, alcohol risk, multi-morbidity, physical activity, physical HRQoL, mental HRQoL and fear of falling (see Suppl. Table 6).

Physical HRQoL

Both the crude and adjusted linear regression models showed that participants who reported ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ fear of falling showed significantly lower physical HRQoL scores compared to participants who reported ‘low’ fear of falling (β = -6.08, 95%CI -7.05 to -5.11 and β = -13.08, 95%CI -14.29 to -11.86) for the adjusted model of ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ compared to ‘low’ fear of falling respectively; Table 2). Using the continuous fear of falling score, a higher fear of falling score was associated with lower physical HRQoL scores (Beta -0.426, P < 0.001) see Suppl. Table 1.

Mental HRQoL

Both the crude and adjusted linear regression models showed that participants who reported ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ fear of falling reported significantly lower mental HRQoL scores compared to participants who reported ‘low fear of falling (β = -2.26, 95%CI -3.28 to -1.25 and β = -8.56, 95%CI -9.84 to -7.29) for the adjusted model of ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ compared to ‘low’ fear of falling respectively; (Table 3). Using the continuous fear of falling score, a higher fear of falling score was associated with lower mental HRQoL scores (Beta -0.345, P < 0.001) see Suppl. Table 1.

Interaction analyses

A significant interaction term was observed for physical HRQoL between fear of falling score and gender (P < 0.001) and fear of falling score and physical activity (P < 0.001). There were no other interaction effects for physical HRQoL (P < 0.05). For mental HRQoL, a significant interaction was observed between fear of falling score and country (P < 0.001). There were no other interaction effects for mental HRQoL (P < 0.05). (Suppl. Table 2).

Stratified analyses for gender indicated a beta for fear of falling score of β = -1.37 (95%CI -1.54 to -1.20) for males and β = -0.92 (95%CI -1.03 to -0.81) for females with regard to physical HRQoL (Suppl. Table 3). For physical activity and physical HRQoL, the beta for the stratum of physical activity once a week or less was β = -0.85 (95%CI -0.98 to -0.72), and for the stratum of physical activity more than once a week β = -1.31 (95%CI -1.44 to -1.17) (Suppl. Table 4).

With regard to mental HRQoL, stratified analyses per country indicated the following beta’s for fear of falling scores for participants from United Kingdom β = -0.41 (95%CI -0.60 to -0.22), Greece β = -0.57 (95%CI -0.84 to -0.31), Croatia β = -0.63 (95%CI -0.79 to -0.46), the Netherlands β = -0.52 (95%CI -0.88 to -0.15), and Spain β = -0.61 (95%CI -0.92 to -0.30) (Suppl. Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, a negative association between fear of falling and physical and mental HRQoL, corrected for previous falls, was observed among community-dwelling older persons of 70 years and older in five European countries. The effect size between participants of the ‘low’ and ‘high’ fear of falling subgroups was large for both physical and mental HRQoL. Results concerning the prevalence of moderate and high fear of falling (29.6% and 20.3%, respectively) are comparable to prevalence numbers reported in other studies, although measurement tools to define prevalence numbers have differed [6, 7, 9,10,11]. Women in this study reported a higher prevalence of high fear of falling compared to men in our study, which is also in line with previous research [8, 32]. The negative association between fear of falling and physical and mental HRQoL observed in our study confirms previous studies' findings [8, 39]. Previous research showed that fear of falling often increases after experiencing a previous fall [15]. However, our findings indicate that the negative association with HRQoL holds even corrected for previous falls. (Data not shown.) While previous studies confirmed the negative impact of fear of falling mostly in specific subgroups, such as patients with chronic conditions [40, 41] or frail older persons [39], this study underlines the presence and need for support in a sample of community-dwelling older persons.

Cohen’s d effect size comparing participants of the ‘low’ and ‘high’ fear of falling subgroups for physical and mental HRQoL indicated a large effect for both with d ≥ 0.80 (Table 1). Moreover, participants who reported moderate fear of falling experienced significantly lower physical HRQoL compared to participants who reported low fear of falling. Physical HRQoL refers to an individual’s or a group’s perceived physical health over time [42]. Fear of falling may be associated with physical inactivity behavior among older persons [16]. This association is of concern as muscle strength and activity generally decline with older age [43]. Physical inactivity may add to this decline, increasing the risk of falling [44]. A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis has shown significant effects of physical activity promotion on reducing fear of falling [25]. We recommend preventive efforts to support older persons, especially those who experience fear of falling, to stay active to maintain and strengthen physical health [45]. Also, post-fall anxiety can further contribute to deconditioning, weakness and abnormal gait due to avoiding activity by being too careful [16]. Therefore, health professionals need to be aware of the associations between fear of falling, experiencing a fall, physical activity behaviors, physical health and physical HRQoL of older persons.

There was a significant interaction between fear of falling and gender in the association with physical HRQoL; in the male subgroup, the association between fear of falling and physical HRQoL was significant. In the literature, the crude prevalence of fear of falling was higher in females than in males [8, 38]. Our data support this difference; however, we did not test for this. These findings need to be confirmed by future studies, as also the sample size in the high fear of falling subgroups in men was low (n = 112). Another possible explanation for the interaction between gender and fear of falling, is that both the female gender and frailty have been reported to increase the risk of having fear of falling [46].

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to report an association between fear of falling and lower mental HRQoL in community-dwelling older persons. Mental HRQoL reflects an individual’s or a group’s perceived mental health over time [42]. The negative association between fear of falling and mental health may be bidirectional. Fear of falling is associated with the emergence of depressive symptoms and impaired executive functioning; on the other hand, clinical depression may be associated with the emergence of redundant fear of falling [47, 48]. We recommend that future studies use longitudinal data to evaluate the direction of the association and the pathways between fear of falling and mental HRQoL. A randomized controlled trial performed among 415 community-dwelling older adults aged 60 years and over, both sexes, with a FES-I score of > 23, showed a significant reduction in fear of falling using cognitive behavioral therapy [49]. These type of interventions might potentially impact fear of falling and mental HRQoL.

The pathways between fear of falling and both mental and physical HRQoL might be influenced by different factors [50]. For example, activity avoidance might affect mental HRQoL because of less social interaction. While physical HRQoL is also affected by activity avoidance, but more on the pathway of loss of muscle strength. These factors can be important to tailor specific psychological or physical care for older persons who experience fear of falling to help them cope with challenges in their daily life [8, 51].

Methodological considerations

A strength of this study is that we were able to analyze a large set of data from a general community-dwelling population across five European countries. The associations between fear of falling and physical and mental HRQoL were studied using validated measurement instruments (i.e. FES-I and SF-12) [19]. A diverse sample of older persons living independently in the community was studied, adding to the existing literature that mainly focused on subgroups such as frail older persons and persons with specific chronic conditions [40, 41]. The following methodological considerations should be taken into account. First, the study’s cross-sectional design does not allow for a causal interpretation of the relationship between fear of falling and HRQoL. Second, some selection bias might have occurred because of excluding persons who were not fluent in the local language. Third, all outcome measures were self-reported using validated questionnaires. Fourth, there is a big difference between the incidence of high fear of falling within countries; even while using validated questionnaires, such as the FES-I, differences in interpretability between countries cannot be ruled out fully. A possible explanation for this difference is that Croatia, within our study population, has the highest proportion of women, the highest proportion of people who exercise once or less a week, and the lowest physical HRQoL score. Fifth, only the main outcomes, physical and mental health-related quality of life, of the SF-12 were used as co-variates; not subdomains, like social functioning or physical role domains. We recommend future research to explore the associations between subdomains of health-related quality of life and falls. Finally, although correction for potential confounders was applied in the analyses, there may be unmeasured or residual confounding.

To conclude, this study showed an association between higher perceived levels of fear of falling and lower physical and mental HRQoL in a large European multi-country population of community-dwelling older persons. The findings emphasize the relevance for health professionals to assess and address fear of falling, recommend preventive programs to promote physical activity, reduce fear of falling, and maintain or increase physical strength and physical and mental HRQoL.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- β:

-

Beta

- 95% CI:

-

95% Confidence interval

- ANOVA:

-

One-way analysis of variance

- AUDIT-C:

-

Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption

- HRQoL:

-

Health-Related Quality of Life

- ISCED:

-

International Standard Classification of Education

- MCS:

-

Mental Component Summary of the SF-12

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCS:

-

Physical Component Summary of the SF-12

- SF-12 :

-

The 12-Item Short Form Health Survey

- Short FES-I :

-

Falls Efficacy Scale International Short

- UHCE :

-

Urban Health Centres Europe

References

United Nations Department of Economic and Social affairs. World Population Prospects: United Nations. 2017.

Eurostat. Population structure and ageing: Eurostat; 2021. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_ageing#The_share_of_elderly_people_continues_to_increase.

Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21(5):658–68.

Morrison A, Fan T, Sen SS, Weisenfluh L. Epidemiology of falls and osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:9–18.

Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson LM, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD007146.

Howland J, Lachman ME, Walker Peterson E, Cote J, Kasten L, Jette A. Covariates of Fear of Falling. Gerontologist. 1998;38(5):549–55.

Tinetti ME, Mendes de Leon CF, Doucette JT, Baker DI. Fear of falling and fall-related efficacy in relationship to functioning among community-living elders. J Gerontol. 1994;49(3):M140-7.

Suzuki M, Ohyama N, Yamada K, Kanamori M. The relationship between fear of falling, activities of daily living and quality of life among elderly individuals. Nurs Health Sci. 2002;4(4):155–61.

Scheffer AC, Schuurmans MJ, van Dijk N, van der Hooft T, de Rooij SE. Fear of falling: measurement strategy, prevalence, risk factors and consequences among older persons. Age Ageing. 2008;37(1):19–24.

Jørstad EC, Hauer K, Becker C, Lamb SE, ProFa NEG. Measuring the psychological outcomes of falling: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):501–10.

Hauer KA, Kempen GI, Schwenk M, Yardley L, Beyer N, Todd C, et al. Validity and sensitivity to change of the falls efficacy scales international to assess fear of falling in older adults with and without cognitive impairment. Gerontology. 2011;57(5):462–72.

Tinetti ME, Powell L. Fear of falling and low self-efficacy: A cause of dependence in elderly persons. J Gerontol. 1993;48(Spec Issue):35–8.

Belloni G, Büla C, Santos-Eggimann B, Henchoz Y, Fustinoni S, Seematter-Bagnoud L. Is Fear of Falling Associated With Incident Disability? A Prospective Analysis in Young-Old Community-Dwelling Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(2):464-7.e4.

Kim J-H, Bae SM. Association between Fear of Falling (FOF) and all-cause mortality. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;88:104017.

Friedman SM, Munoz B, West SK, Rubin GS, Fried LP. Falls and fear of falling: which comes first? A longitudinal prediction model suggests strategies for primary and secondary prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(8):1329–35.

Rubenstein LZ. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing. 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii37–41.

Esbrí-Víctor M, Huedo-Rodenas I, López-Utiel M, Navarro-López JL, Martínez-Reig M, Serra-Rexach JA, et al. Frailty and Fear of Falling: The FISTAC Study. J Frailty Aging. 2017;6(3):136–40.

World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. p. 2015.

Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking Clinical Variables With Health-Related Quality of Life: A Conceptual Model of Patient Outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65.

Ferrans CE. Definitions and conceptual models of quality of life. In: Gotay CC, Snyder C, Lipscomb J, editors. Outcomes Assessment in Cancer: Measures, Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. p. 14–30.

Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A, Capoluongo E, Barillaro C, Pahor M, et al. Disability, more than multimorbidity, was predictive of mortality among older persons aged 80 years and older. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):752–9.

Schoene D, Heller C, Aung YN, Sieber CC, Kemmler W, Freiberger E. A systematic review on the influence of fear of falling on quality of life in older people: is there a role for falls? Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:701–19.

Denkinger MD, Lukas A, Nikolaus T, Hauer K. Factors associated with fear of falling and associated activity restriction in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(1):72–86.

Choi K, Ko Y. Characteristics Associated With Fear of Falling and Activity Restriction in South Korean Older Adults. J Aging Health. 2015;27(6):1066–83.

Kumar A, Delbaere K, Zijlstra GA, Carpenter H, Iliffe S, Masud T, et al. Exercise for reducing fear of falling in older people living in the community: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):345–52.

Franse CB, van Grieken A, Alhambra-Borras T, Valia-Cotanda E, van Staveren R, Rentoumis T, et al. The effectiveness of a coordinated preventive care approach for healthy ageing (UHCE) among older persons in five European cities: A pre-post controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;88:153–62.

Franse CB, Voorham AJJ, van Staveren R, Koppelaar E, Martijn R, Valia-Cotanda E, et al. Evaluation design of Urban Health Centres Europe (UHCE): preventive integrated health and social care for community-dwelling older persons in five European cities. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):209.

Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen G, Piot-Ziegler C, Todd C. Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing. 2005;34(6):614–9.

Delbaere K, Close JCT, Mikolaizak AS, Sachdev PS, Brodaty H, Lord SR. The Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I). A comprehensive longitudinal validation study. Age and Ageing. 2010;39(2):210–6.

Kempen GI, Yardley L, van Haastregt JC, Zijlstra GA, Beyer N, Hauer K, et al. The Short FES-I: a shortened version of the falls efficacy scale-international to assess fear of falling. Age Ageing. 2008;37(1):45–50.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1171–8.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. International Standard Classification of Education, ISCED 2011. 2012.

World Health Organization. Multimorbidity: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–95.

Quah JHM, Wang P, Ng RRG, Luo N, Tan NC. Health-related quality of life of older Asian patients with multimorbidity in primary care in a developed nation. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(10):1429–37.

Malter FaAB-SE. SHARE Wave 5: Innovations & Methodology. Munich: MEA, Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy; 2015.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Erlbaum Publishers; 2013.

Bjerk M, Brovold T, Skelton DA, Bergland A. Associations between health-related quality of life, physical function and fear of falling in older fallers receiving home care. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):253.

Grimbergen YA, Schrag A, Mazibrada G, Borm GF, Bloem BR. Impact of falls and fear of falling on health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3(3):409–13.

Buker N, Eraslan U, Kitis A, Kiter AE, Akkaya S, Sutcu G. Is quality of life related to risk of falling, fear of falling, and functional status in patients with hip arthroplasty? Physiother Res Int. 2019;24(3):e1772.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion DoPH. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL): Centers for DIsease Control and Prevention; 2021 [updated 16–06–2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/index.htm.

Aartolahti E, Lönnroos E, Hartikainen S, Häkkinen A. Long-term strength and balance training in prevention of decline in muscle strength and mobility in older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(1):59–66.

Menant JC, Weber F, Lo J, Sturnieks DL, Close JC, Sachdev PS, et al. Strength measures are better than muscle mass measures in predicting health-related outcomes in older people: time to abandon the term sarcopenia? Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(1):59–70.

Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, Tiedemann A, Michaleff ZA, Howard K, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1(1):CD012424.

Almada M, Brochado P, Portela D, Midão L, Costa E. Prevalence of Fall and Associated Factors Among Community-Dwelling European Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Frailty Aging. 2021;10(1):10–6.

Iaboni A, Flint AJ. The complex interplay of depression and falls in older adults: a clinical review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(5):484–92.

Turunen KM, Kokko K, Kekäläinen T, Alén M, Hänninen T, Pynnönen K, et al. Associations of neuroticism with falls in older adults: do psychological factors mediate the association? Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(1):1–9.

Parry SW, Bamford C, Deary V, Finch TL, Gray J, MacDonald C, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy-based intervention to reduce fear of falling in older people: therapy development and randomised controlled trial - the Strategies for Increasing Independence, Confidence and Energy (STRIDE) study. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(56):1–206.

Gottschalk S, König HH, Schwenk M, Jansen CP, Nerz C, Becker C, et al. Mediating factors on the association between fear of falling and health-related quality of life in community-dwelling German older people: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):401.

Rivasi G, Kenny RA, Ungar A, Romero-Ortuno R. Predictors of Incident Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(5):615–20.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Daan Nieboer, MSc, Department of Public Health, Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam, for his advice on the statistical analyses.

Funding

The UHCE project was supported by the European Union, CHAFEA, third health programme, grant number 20131201. The funding body played no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed by SK, ST and AG. SK, ST, and AG analyzed and interpreted the data. SK drafted the manuscript. AG was a major contributor to writing the manuscript. AV, TA, CF and HR have contributed to the design and the data collection of the Urban Health Centers Europe study and have revised the current manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical committee procedures have been followed in all cities and institutions involved, and approval has been provided. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines. The names of the review board and the approval references are: Manchester, United Kingdom: NRES Committee West Midlands—Coventry & Warwickshire; 06–03-2015; 15/WM/0080; NRES Committee South Central – Berkshire B; 29–20-2014; 14/SC/1349; Pallini, Greece: The Ethics and Scientific board—Latriko Palaiou Falirou Hospital; 04/03/2015; 20150304–01; Rijeka, Croatia: The Ethical Committee—Faculty of Medicine University of Rijeka; 07–04-2014; 2170–24-01–14-02; Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Medische Ethische Toetsings Commissie (METC) – Erasmus MC Rotterdam; 08/01/2015; MEC-2014–661; Valencia, Spain: Comisión de Investigación—Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia. 29/01/2015; CICHGUV-2015–01-29. Written informed consent is obtained from all participants. The data used in this study were anonymized before its use.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1.

Participants flow chart. Supplementary Table 1. Fear of Falling score and physical and mental Health-Related Quality of Life (n=2189). Supplementary Table 2. P-values and coefficients for interaction analyses for Fear of Falling score in the association with physical and mental HRQoL (n=2040). Supplementary table 3. The association between Fear of Falling score and physical HRQoL, stratified by gender (n=2040). Supplementary table 4. The association between Fear of Falling score and physical HRQoL, stratified by physical activity level (n=2040). Supplementary table 5. The association between Fear of Falling score and mental HRQoL, stratified by country (n=2040). Supplementary Table 6. Comparison of included and excluded participants (n=2325).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Korenhof, S. ., van Grieken, A., Franse, C.(. et al. The association of fear of falling and physical and mental Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) among community-dwelling older persons; a cross-sectional study of Urban Health Centres Europe (UHCE). BMC Geriatr 23, 291 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04004-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04004-y