Abstract

Background

Research on potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) and medication-related problems (MRP) among the Chinese population with chronic diseases and polypharmacy is insufficient.

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of PIM and MRP among older Chinese hospitalized patients with chronic diseases and polypharmacy and analyze the associated factors.

Methods

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted in five tertiary hospitals in Beijing. Patients aged ≥ 65 years with at least one chronic disease and taking at least five or more medications were included. Data were extracted from the hospitals’ electronic medical record systems. PIM was evaluated according to the 2015 Beers criteria and the 2014 Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions (STOPP) criteria. MRPs were assessed and classified according to the Helper-Strand classification system. The prevalence of PIM and MRP and related factors were analyzed.

Results

A total of 852 cases were included. The prevalence of PIM was 85.3% and 59.7% based on the Beers criteria and the STOPP criteria. A total of 456 MRPs occurred in 247 patients. The most prevalent MRP categories were dosages that were too low and unnecessary medication therapies. Hyperpolypharmacy (taking ≥ 10 drugs) (odds ratio OR 3.736, 95% confidence interval CI 1.541–9.058, P = 0.004) and suffering from coronary heart disease (OR 2.620, 95%CI 1.090–6.297, P = 0.031) were the influencing factors of inappropriate prescribing (the presence of either PIM or MRP in a patient).

Conclusion

PIM and MRP were prevalent in older patients with chronic disease and polypharmacy in Chinese hospitals. More interventions are urgently needed to reduce PIM use and improve the quality of drug therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The aging of the population presents formidable challenges in healthcare systems, which concerns many countries [1, 2]. Chronic diseases, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke, are common in adults over 65 years of age. About three in four older adults in developed countries live with more than one chronic disease [3]. A similar situation was found in China [4]. For treating these coexisting diseases, older patients often take multiple medications, which leads to polypharmacy. More than half of the older population is exposed to polypharmacy in some settings [5, 6]. Polypharmacy increases the risk of adverse drug reactions, drug-drug interactions, medication non-adherence, and inappropriate use of medications [7,8,9]. It promotes the emergence of medication-related problems (MRP) [10]. Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) are medications whose adverse risk exceed their health benefits when prescribed in older adults [11]. They are associated with adverse clinical outcomes such as falls and risk of frailty in the elderly and can lead to higher utilization of healthcare resources and hospital admissions [12]. Furthermore, patients with MRPs have an increased incidence of drug-related adverse events that lead to a higher risk of mortality [13].

There are multiple screening tools to help healthcare providers select medication therapy and reduce the exposure of older adults to PIM use (PIMU). Among them, the American Geriatric Society (AGS) Beers Criteria [14] and Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions (STOPP) are the two most widely used criteria [15]. The Beers criteria was initially published in 1991 by the American Geriatrics Society and the latest version has been available since 2019 [16]. The STOPP criteria was first launched by geriatricians from Cork University Hospital (Ireland) in 2008 and was updated in 2014 [15]. Most published studies on PIMU and MRPs focused on investigating the incidences and factors influencing them. Only a few studies explored the relationship between chronic diseases and PIMU. An investigation determined and assessed the magnitude and predictors of PIMU in older adult patients at the chronic care clinic in southwest Ethiopia [17]. According to Beers and STOPP criteria, at least one PIMU was identified in 83.1% and 45.2% of the patients, respectively. The risk of PIMU according to the Beers criteria increased with age, hypertension, and polypharmacy. Using STOPP criteria, hypertension, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, peripheral neuropathy, and polypharmacy significantly increased the risk of PIMU. Another study conducted in the United States investigated the associations between chronic illness, polypharmacy, and MRPs among Medicare beneficiaries (65 years and older) [18]. The study found that beneficiaries with certain conditions were more likely to suffer from MRP than those without, including depression, congestive heart failure, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, respiratory disorders, and hypertension. Medicare beneficiaries with 11 or more medications were 1.86 times more likely to experience an MRP than those taking fewer medications.

Several studies have investigated PIMU and MRP in Chinese older adults [19,20,21,22]. These studies have revealed a high prevalence of PIMU and MRP in aging adult populations. However, information on PIMU and MRP and related factors in older adults with chronic diseases and polypharmacy are still limited. Here, we conducted a multicenter cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence of PIMU and MRP among older Chinese hospitalized patients with chronic diseases and polypharmacy. We also sought to identify factors associated with PIMU and MRP among the study population to help clinicians manage at-risk patients by improving the rational use of medications.

Methods

Study design and population

This retrospective study was conducted in five tertiary hospitals in Beijing (Xuanwu Hospital, Shijitan Hospital, Anzhen Hospital, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, and Luhe Hospital). We included patients discharged from the Department of Neurology, Geriatrics, Cardiology, and Endocrinology in the first week of each month in March, June, September, and December 2017. The study inclusion criteria were 1) patients 65 years or older, and 2) had at least one of the following five chronic diseases as discharge diagnoses: hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, cerebral infarction, and type 2 diabetes. Only polypharmacy or hyperpolypharmacy patients were included in the analysis. Polypharmacy was defined as the concurrent use of five to nine drugs during hospitalization, and hyperpolypharmacy was defined as taking 10 or more drugs [23]. Patients were excluded from the study if they were hospitalized for less than 48 h, admitted multiple times within a month, or transferred from or to the intensive care unit.

Data collection

The study data were obtained from the hospitals’ electronic medical record systems. We designed the case report form and used the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system to manage the form electronically. Data quality control was conducted regularly. The following data were collected: the patient’s personal information (date of birth, gender, height, and weight), hospitalization information (discharge department, date of admission, date of discharge, past medical history, discharge diagnoses, type of health insurance, and laboratory test results) and medication information (drug name, indications, dosage, and adverse reactions). Information concerning traditional Chinese medicines, solvents, temporary medication orders, topical drugs, and hospital preparations was not collected as PIM criteria usually do not apply to these. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score was calculated based on the diagnoses at discharge [24]. Drugs were classified according to the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System (http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index). Each patient was assigned a unique code. All data were de-identified.

The assessment of PIMU and MRP

PIMU was assessed separately according to the 2015 AGS Beers Criteria and the 2014 STOPP Criteria, the latest versions available at the time of research. Taking at least one item (drug or drug class) listed in either criterion was considered PIMU. The following Beers criteria items (total 87) were assessed: category A-avoided by most older people, category B-avoided by older people with specific health conditions (drug-disease or drug-syndrome interactions), category C-medications to be used with caution, category D-avoided in combination with other treatments because of the risk of harmful “drug-drug” interactions, and category E-dosed differently or avoided among people with reduced kidney function (Supplemental Table 1). Not all STOPP items could be appropriately assessed based on available clinical information. Therefore, the expert panel of the study selected 53.1% (43/81) of the STOPP criteria items for PIM identification (Supplemental Table 2).

The MRP was assessed using the Helper-Strand classification. MRPs were classified into six categories (unnecessary medication therapy, need for additional medication therapy, ineffective medication, dosage too low, adverse drug event, and dosage too high) and 26 causes [25]. Medication adherence was not evaluated due to the lack of documentation in electronic medical records. In this study, inappropriate prescribing was the presence of either a PIM or MRP in a patient.

Statistical analysis

Variables included age, gender, department, number of diagnoses at discharge, number of drugs, health insurance, CCI, length of hospital stay, and chronic conditions. These variables were used to analyze the influencing factors of PIMU and MRP.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the general characteristics of the study population and the prevalence of PIM and MRP. Categorical variables are expressed as counts and proportions (%). Continuous variables are expressed as medians and 25 and 75 percentiles (P25, P75) because the data did not conform to the normal distribution. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test and the Chi-squared test were used to compare the groups. A logistic regression model was used to analyze the influencing factors of PIMU and MRP. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were derived from this model. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

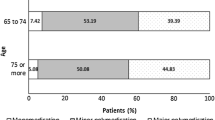

A total of 852 cases were included in the analysis. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the study population. The median age was 74 years, and 50.6% (431/852) were females. The median CCI score was 2 points. The majority (90.1%, 768/852) had health insurance. The median hospital stay was nine days, and the median number of discharge diagnoses was eight. Hypertension (77.5%, 660/852), hyperlipidemia (65.3%, 556/852), and coronary heart disease (59.3%, 505/852) were the top three chronic diseases. The patients had an average of 2.9 coexisting chronic diseases. The median number of drugs prescribed was 10. A total of 48.7% (415/852) of patients were polypharmacy patients and 51.3% (437/852) were hyperpolypharmacy patients.

Table 2 shows the top ten most prescribed drug classes. More than half of the patients took antithrombotic agents (84.5%, 720/852), lipid-modifying agents (84.2%, 717/852), and other cardiac preparations (52.5%, 447/852).

The prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use

The prevalence of PIMU in this study was 93.8% (799/852), an average of 2.7 PIMs per patient. A total of 20.4% (174/852) of patients took one PIM, and 73.4% (625/852) took two or more PIMs (Table 3). According to Beers Criteria, 85.3% (727/852) of the patients received PIMs that included 47.1% (41/87) of the PIM items. Details are shown in Supplemental Table 1. However, according to the STOPP criteria, 59.7% (509/852) of patients received PIMs which included 81.4% (35/43) of the PIM items. Details are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

The PIM prevalence rates were higher in the following Beers criteria items: 1) vasodilators-use with caution, 65.5% (558/852), 2) proton-pump inhibitors (PPI)-avoid scheduled use for > eight weeks, 32.4% (276/852), 3) antipsychotics and diuretics-may exacerbate or cause syndromes of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion or hyponatremia-use with caution, 31.7% (270/852), 4) short-and intermediate-acting benzodiazepines-avoid, 7.6% (65/852), and 5) aspirin for primary prevention of cardiac events-use with caution in adults aged ≥ 80, 4.3% (37/852). Details are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

The following STOPP criteria items had higher prevalence rates: 1) C8 (NSAID with concurrent antiplatelet agent without PPI prophylaxis), 21.7% (185/852), 2) N1 (concomitant use of two or more drugs with antimuscarinic/anticholinergic properties), 10.6% (90/852), 3) A1 (any drug prescribed without an evidence-based clinical indication), 10.3% (88/852), 4) C3 (aspirin plus clopidogrel as secondary stroke prevention), 10.0% (85/852), and 5) K1 (benzodiazepines), 8.2% (70/852). Details are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

The analysis of medication-related problems

The analysis of the prevalence of MRP is presented in Tables 3 and 4. A total of 247 patients (29%, 247/852) had MRP (144 hyperpolypharmacy patients and 103 polypharmacy patients). A total of 54.3% (134/247) had one MRP. Dosage too low occurred in 41.3% (102/247) of patients followed by 40.9% (101/247) of patients with unnecessary medication therapy. The prevalent rates of unnecessary medication therapy (14.9% vs. 8.7%, P = 0.005), ineffective medication (3.9% vs. 0.7%, P = 0.002), dosage too low (14.9% vs. 8.9%, P = 0.007), and dosage too high (10.1% vs. 5.3%, P = 0.009) were significantly higher in hyperpolypharmacy patients than in polypharmacy patients.

Table 5 shows the analysis of MRP causes. The most common causes of MRPs were no medication indication (28.3%, 129/456), dosage too low to produce the desired response (25.4%, 116/456), and dosage too high (10.1%, 46/456).

Factors associated with PIM, MRP, and inappropriate prescribing

Table 6 reports the results of the multivariate logistic regression of PIM, MRP and inappropriate prescribing (the presence of either PIM or MRP). The cardiology department had the highest proportion of patients with PIM and the lowest proportion of patients with MRP and was chosen as the reference department. Inappropriate prescribing was associated with hyperpolypharmacy (OR 3.736, 95%CI 1.541–9.058, P = 0.004) and coronary heart disease (OR 2.62, 95%CI 1.09–6.297, P = 0.031). Patients attending cardiology had a significantly higher risk of PIM when compared to those attending endocrinology (OR 0.085, 95%CI 0.029–0.247, P < 0.01). The occurrence of MRP was most significant in the male gender (OR 1.448, 95%CI 1.057–1.983, P = 0.021) and with hyperpolypharmacy (OR 1.583, 95%CI 1.114–2.248, P = 0.01). Patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia had fewer MRPs (OR 0.54, 95%CI 0.386–0.756, P < 0.001). Patients attending the geriatrics (OR 3.674, 95%CI 2.089–6.459, P < 0.001) and neurology (OR 2.274, 95% CI 1.451–3.566, P < 0.001) departments had significantly higher MRP prevalence rates than those attending the cardiology department.

Discussion

This is the first multicenter study analyzing PIM and MRP in Chinese hospitalized patients with chronic disease and polypharmacy or hyperpolypharmacy. The prevalence of PIM was high, 93.8% in this population. The incidence of MRP was 29.0%, and the most prevalent MRP categories were dosage too low and unnecessary medication therapy. Hyperpolypharmacy and the presence of coronary heart disease were the influencing factors of PIMU.

Due to data availability and prescribing habits, PIMU varies significantly between countries, regions, and populations. A study evaluated the incidence of PIMU in older patients hospitalized for chronic disease exacerbation in five hospitals in Spain. The results showed that 81.5% of the patients had at least one PIM [26]. The incidence rate of PIMU was 73.2% according to the 2014 STOPP criteria. Another study analyzed the prevalence of PIMU in older patients in an internal medicine department of a Portuguese hospital. The results showed that according to the 2019 Beers criteria and the 2014 STOPP criteria, 92.0% and 76.5% of the patients used at least one PIM, respectively [27]. An analysis of PIMU for older patients with polypharmacy in nine tertiary hospitals in Chengdu, China, found that the incidence of PIMU was 72.54% according to the 2015 Beers criteria [28]. Compared to these studies, the incidence of PIMU in this study was higher, which could be due to the population being patients with chronic diseases and polypharmacy or hyperpolypharmacy. Since there are overlaps and differences between different PIM judgment criteria [29], the combination of Beers criteria and STOPP criteria can detect more PIMs.

PIMs in this study population differed from our previous study among outpatients [30]. In this study, the most common PIM item according to the Beers criteria was vasodilators. Vasodilators should be used with caution in older adults whose vasodilatory effects causing orthostatic hypotension and exacerbating syncope attacks in patients with a history of syncope. More than half of the study patients had coronary heart disease, and about half were treated with isosorbide mononitrate. Isosorbide mononitrate reduces myocardial oxygen consumption, improves myocardial perfusion, and relieves symptoms of angina pectoris. It is recommended for patients with objective evidence of ischemia [31]. To reduce the risk of hypotension and even falls caused by nitrates, older patients should start with a lower dose, adjust the dose according to treatment response, and pay attention to drug resistance over long-term use [32]. However, vasodilators were removed from the 2019 Beers criteria due to the risk not being unique to older patients [16] and the prevalence of PIM was expected to decrease according to this version criteria. PPIs were the second most commonly prescribed PIM item in this study population, and the incidence is similar to that of other related studies, 11.3%-42.6% [33, 34]. PPIs are commonly used in treating peptic ulcers and chronic gastritis and are also widely used to prevent stress ulcers in hospitalized patients [35]. The long-term use of PPI in older patients leaves the patients more prone to complications such as Clostridium difficile infection or renal toxicity [36]. Therefore, pharmacists should focus on reviewing indications for PPI use and avoid unnecessary use for more than eight weeks. According to the STOPP criteria, the most common PIM item was the combined use of NSAIDs and antiplatelet drugs but without the prophylactic use of PPIs. NSAIDs should be avoided in patients with a high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. If necessary, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors can be selected to be taken with PPIs to prevent drug-related gastrointestinal mucosal injury [37].

The incidence of MRP in this study was 29.0%, lower than that of several other studies which had rates of 63.3% to 70.8% [38, 39]. The rates of MRP occurrences and categories vary based on the study population and the classification tools used. In our study, the analyzed medications were long-term treatments for chronic diseases and might have already been optimized. Furthermore, the MRP evaluation was based on a retrospective review of electronic medical record systems. The most common MRP categories were dosage too low and unnecessary medication therapy. The results suggest that clinicians should not only pay attention to the overtreatment of patients with polypharmacy and streamline prescriptions but also be aware of the potential undertreatment [40, 41]. Suboptimal dosing increases the risk of disease exacerbation leading to increased utilization of healthcare resources [42, 43].

Hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, cerebral infarction, and hyperlipidemia are common chronic diseases in older adults [30]. Comorbidities such as endocrine and metabolic disorders, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease were factors of polypharmacy in older adults [44,45,46]. Our study investigated PIMU in patients with chronic diseases and polypharmacy or hyperpolypharmacy. The results show that people with coronary heart disease had increased PIMU. Hyperlipidemia might be a protective factor for the development of MRP. However, this was not reflected in the results of the influencing factors of PIMU and needed to be confirmed by subsequent larger sample size studies. Our study found that the occurrence of PIM and MRP was related to the number of drugs. Hyperpolypharmacy was associated with an increase in PIM and MRP. The results are consistent with previous studies [17, 18, 39, 47]. Clinicians should carefully review drug therapies and detect PIMs in patients with hyperpolypharmacy. Unlike other studies [30, 48], the risk of MRP was higher in male patients in our study.

Our study has several limitations. First, the retrospective review may lead to underestimating PIMU and MRP. Second, we only included patients with common chronic diseases, which may cause selection bias. And the setting of inclusion and exclusion criteria may affect the generalizability of the results. Third, we did not use the most recent Beers criteria (2019). Finally, this study included patients from tertiary hospitals in Beijing, and the findings may not represent community hospitals or other areas. More extensive sample and multiregional studies are still needed to support the conclusion of this study.

Conclusion

The prevalence of PIM and MRP is high in older hospitalized patients with chronic disease and polypharmacy or hyperpolypharmacy. Coronary heart disease and hyperpolypharmacy were associated with an increase in PIMU. More interventions are urgently needed to reduce PIMU in this patient population.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the restriction under the institutional ethical committee’s policy, but may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission of the ethical committee.

Abbreviations

- PIM:

-

Potentially inappropriate medications

- MRP:

-

Medication-related problems

- STOPP:

-

Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions

- PIMU:

-

Potentially inappropriate medication use

- AGS:

-

American Geriatric Society

- REDCap:

-

Research Electronic Data Capture

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- ATC:

-

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

- PPI:

-

Proton-pump inhibitors

References

Fang EF, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Jahn HJ, Li J, Ling L, Guo H, et al. A research agenda for aging in China in the 21st century. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;24(Pt B):197–205.

Yancik R. Population aging and cancer: a cross-national concern. Cancer J. 2005;11(6):437–41.

Hajat C, Stein E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: a narrative review. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:284–93.

Wang LM, Chen ZH, Zhang M, Zhao ZP, Huang ZJ, Zhang X, et al. Study of the prevalence and disease burden of chronic disease in the elderly in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2019;40(3):277–83.

Pazan F, Wehling M. Polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review of definitions, epidemiology and consequences. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(3):443–52.

Wastesson JW, Morin L, Tan ECK, Johnell K. An update on the clinical consequences of polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(12):1185–96.

Rodrigues MC, Oliveira C. Drug-drug interactions and adverse drug reactions in polypharmacy among older adults: an integrative review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2016;24: e2800.

Pasina L, Brucato AL, Falcone C, Cucchi E, Bresciani A, Sottocorno M, et al. Medication non-adherence among elderly patients newly discharged and receiving polypharmacy. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(4):283–9.

Abdulah R, Insani WN, Destiani DP, Rohmaniasari N, Mohenathas ND, Barliana MI. Polypharmacy leads to increased prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication in the Indonesian geriatric population visiting primary care facilities. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:1591–7.

Troncoso-Mariño AA-O, López-Jiménez T, Roso-Llorach A, Villén N, Amado-Guirado E, Guisado-Clavero M, et al. Medication-related problems in older people in Catalonia: a real-world data study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30(2):220–8.

Alwhaibi M. Potentially inappropriate medications use among older adults with comorbid diabetes and hypertension in an ambulatory care setting. J Diabetes Res. 2022;2022:1591511.

Fernández A, Gómez F, Curcio CL, Pineda E, Fernandes de Souza J. Prevalence and impact of potentially inappropriate medication on community-dwelling older adults. Biomedica. 2021;41(1):111–22.

Troncoso-Mariño A, Roso-Llorach AA-O, López-Jiménez T, Villen N, Amado-Guirado E, Fernández-Bertolin S, et al. Medication-related problems in older people with multimorbidity in Catalonia: a real-world data study with 5 years’ follow-up. J Clin Med. 2021;10(4):709.

By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–46.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–8.

The 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–694.

Tesfaye BT, Tessema MT, Yizengaw MA, Bosho DD. Potentially inappropriate medication use among older adult patients on follow-up at the chronic care clinic of a specialized teaching hospital in Ethiopia. a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):530.

Almodóvar AS, Nahata MC. Associations between chronic disease, polypharmacy, and medication-related problems among medicare beneficiaries. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(5):573–7.

Chen Q, Zhang L. Analysis of potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) used in elderly outpatients in departments of internal medicine by using the Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (STOPP) criteria. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(4):4678–86.

Fu M, Wushouer H, Nie X, Shi L, Guan X, Ross-Degnan D. Potentially inappropriate medications among elderly patients in community healthcare institutions in Beijing, China. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29(8):923–30.

Meng L, Qu C, Qin X, Huang H, Hu Y, Qiu F, et al. Drug-related problems among hospitalized surgical elderly patients in China. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:8830606.

Yang J, Meng L, Liu Y, Lv L, Sun S, Long R, et al. Drug-related problems among community-dwelling older adults in mainland China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(2):368–75.

Schöttker B, Saum KU, Muhlack DC, Hoppe LK, Holleczek B, Brenner H. Polypharmacy and mortality: new insights from a large cohort of older adults by detection of effect modification by multi-morbidity and comprehensive correction of confounding by indication. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(8):1041–8.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Tomechko MA, Strand LM, Morley PC, Cipolle RJ. Q and A from the pharmaceutical care project in Minnesota. Am Pharm. 1995;Ns35(4):30–9.

Baré M, Lleal M, Ortonobes S, Gorgas MQ, Sevilla-Sánchez D, Carballo N, et al. Factors associated to potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients according to STOPP/START criteria: MoPIM multicentre cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):44.

Perpétuo C, Plácido AI, Rodrigues D, Aperta J, Piñeiro-Lamas M, Figueiras A, et al. Prescription of potentially inappropriate medication in older inpatients of an internal medicine ward: concordance and overlap among the EU(7)-PIM list and Beers and STOPP criteria. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12: 676020.

Tian F, Liao S, Chen Z, Xu T. The prevalence and risk factors of potentially inappropriate medication use in older Chinese inpatients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: a cross-sectional study. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(18):1483.

Ma Z, Zhang C, Cui X, Liu L. Comparison of three criteria for potentially inappropriate medications in Chinese older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:65–72.

Zeng Y, Yu Y, Liu Q, Su S, Lin Y, Gu H, et al. Comparison of the prevalence and nature of potentially inappropriate medication use in geriatric outpatients between tertiary and community healthcare settings: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44(3):619–29.

Writing Committee Members. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2022;28(5):e1–167.

Dixit D, Kimborowicz K. Pharmacologic management of chronic stable angina. JAAPA. 2015;28(6):1–8.

Sheikh-Taha M, Dimassi H. Potentially inappropriate home medications among older patients with cardiovascular disease admitted to a cardiology service in USA. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):189.

Wang P, Wang Q, Li F, Bian M, Yang K. Relationship between potentially inappropriate medications and the risk of hospital readmission and death in hospitalized older patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1871–8.

Clarke K, Adler N, Agrawal D, Bhakta D, Sata SS, Singh S, et al. Reducing overuse of proton pump inhibitors for stress ulcer prophylaxis and nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding in the hospital: a narrative review and implementation guide. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(7):417–23.

Mafi JN, May FP, Kahn KL, Chong M, Corona E, Yang L, et al. Low-value proton pump inhibitor prescriptions among older adults at a large academic health system. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(12):2600–4.

Alsinnari YM, Alqarni MS, Attar M, Bukhari ZM, Almutairi M, Baabbad FM, et al. Risk factors for recurrence of peptic ulcer disease: a retrospective study in tertiary care referral center. Cureus. 2022;14(2): e22001.

Paisansirikul A, Ketprayoon A, Ittiwattanakul W, Petchlorlian A. Prevalence and associated factors of drug-related problems among older people: a cross-sectional study at King Chulalongkorn memorial hospital in Bangkok. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2021;8(1):73–84.

Kefale B, Degu A, Tegegne GT. Medication-related problems and adverse drug reactions in Ethiopia: a systematic review. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2020;8(5): e00641.

Halli-Tierney AD, Scarbrough C, Carroll D. Polypharmacy: evaluating risks and deprescribing. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(1):32–8.

Cadogan CA, Ryan C, Hughes CM. Appropriate polypharmacy and medicine safety: when many is not too many. Drug Saf. 2016;39(2):109–16.

Cherubini A, Corsonello A, Lattanzio F. Underprescription of beneficial medicines in older people: causes, consequences and prevention. Drugs aging. 2012;29(6):463–75.

Moudallel S, Steurbaut S, Cornu P, Dupont A. Appropriateness of DOAC prescribing before and during hospital admission and analysis of determinants for inappropriate prescribing. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1220.

Jokanovic N, Tan EC, Dooley MJ, Kirkpatrick CM, Bell JS. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(6):535.e1-12.

Nobili A, Marengoni A, Tettamanti M, Salerno F, Pasina L, Franchi C, et al. Association between clusters of diseases and polypharmacy in hospitalized elderly patients: results from the REPOSI study. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(6):597–602.

Arauna D, Cerda A, García-García JF, Wehinger S, Castro F, Méndez D, et al. Polypharmacy is associated with frailty, nutritional risk and chronic disease in chilean older adults: remarks from PIEI-ES study. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:1013–22.

Ma Z, Sun S, Zhang C, Yuan X, Chen Q, Wu J, et al. Characteristics of drug-related problems and pharmacists’ interventions in a geriatric unit in China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(1):270–4.

Wuyts J, Maesschalck J, De Wulf I, Lelubre M, Foubert K, De Vriese C, et al. Studying the impact of a medication use evaluation by the community pharmacist (Simenon): drug-related problems and associated variables. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(8):1100–10.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Peking University Clinical Research Institute for technical support.

Funding

This study was supported by the Beijing Science and Technology Commission Funded Project (D181100000218002) and Beijing Municipal Health Commission Funded Project (11000022T000000444688).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jing Tang, Ke Wang, Dechun Jiang, Su Su, and Suying Yan conceived and designed the study. Jing Tang, Ke Wang, Yang Lin, Shicai Chen, Hongyan Gu, and Pengmei Li participated in data collection. Jing Tang and Ke Wang processed, analyzed, and interpreted the data. Kun Yang and Xianghua Fang participated in data processing and analysis. Suying Yan, Dechun Jiang, and Su Su participated in data interpretation. Jing Tang and Ke Wang drafted the manuscript and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University (Clinical Scientific Research [2018] No.023). All data were de-identified once extracted from the information system. The strict confidentiality of the data was maintained throughout the research process. The need for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, J., Wang, K., Yang, K. et al. A combination of Beers and STOPP criteria better detects potentially inappropriate medications use among older hospitalized patients with chronic diseases and polypharmacy: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 23, 44 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03743-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03743-2